They still grieve—a nationwide follow-up of young adults 2–9 years after losing a sibling to cancer

Abstract

Objectives

The aims of this study were to assess the prevalence of unresolved grief in bereaved young adult siblings and examine possible contributing factors.

Methods

The study was a Swedish population-based study of young adults who had lost a brother or sister to cancer, 2–9 years earlier. Of 240 eligible siblings, 174 (73%) completed a study-specific questionnaire. This study focused on whether the respondents had worked through their grief over the sibling's death and to what extent.

Results

A majority (54%) of siblings stated that they had worked through their grief either ‘not at all’ or ‘to some extent’ at the time of investigation. In multiple regression analyses with unresolved grief as the dependent variable, 21% of the variance was explained by lack of social support and shorter time since loss.

Conclusion

The majority of bereaved young adults had not worked through their grief over the sibling's death. A small group of siblings reported that they had not worked through their grief at all, which may be an indicator of prolonged grief. Lack of social support and more recent loss were associated with not having worked through the grief over the sibling's death. Copyright © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Introduction

The loss of a child to cancer is one of the most traumatic experiences a family can suffer, and it is often preceded by a long period of illness and treatments 1. In the last few decades, the survival rate in childhood cancer has increased dramatically in Western countries. Accordingly, research on the siblings has shifted from bereaved to non-bereaved.

There are several theories of the grief process based on the assumption that the bereaved go through different stages or phases. One such theory is by Bowlby 2, who described grief in four stages: shock–numbness, yearning–protest, despair and recovery. However, these stage theories have been criticised for oversimplifying the grief process. A different approach is by setting tasks that should be worked through for grief to be resolved 3. According to the model, the four tasks of grieving are as follows: accepting the reality of loss; working through the pain of grief; adjusting to the environment without the deceased; and relocating the deceased emotionally and moving on.

The dual-process model by Stroebe and Schut 4 shows another way of explaining how the bereaved cope with their loss. The model assumes that bereaved individuals must work through their emotions and need to adapt to their changed world. The authors suggests that bereaved people oscillates between two types of coping processes, loss orientation (e.g. sadness, helplessness and crying) and restoration orientation (e.g. financial and family demands), which give the bereaved a break from their grief. According to the authors, these coping processes are both necessary in the grief work process.

Even though most individuals experience uncomplicated grief and resolve their grief within 6 months to 2 years after the loss 5, the process of grieving is individual and differs in intensity and duration.

Grief is the emotional and psychological reaction to loss, and common grief reactions in adults are emotional numbness, disbelief, dysphoria and yearning 6, 7. Grief in children and adolescents is different from that in adults 8 as a child's reaction to death is related to his or her concept of death, which in turn is related to the child's developmental stage. Children often grieve for shorter periods than adults 9. Their reactions are not continuous; however, they appear to go in and out of mourning, as a coping mechanism 10. The grief reactions observed in children and adolescents commonly include strong emotions such as guilt, anger and shame, as well as impulsive behaviour 11. Younger children often express their grief behaviourally rather than emotionally 12. In addition, young adults are in a transitional period of late adolescence and may experience many of the developmental challenges of both adolescents and adults.

Studies on bereaved siblings in general have reported emotional problems, such as feelings of sadness, guilt and anxiety, isolation from peers 13-16 and depression 17. Nevertheless, siblings also reported positive outcomes such as increased personal maturity 14, 18 and self-concept 16.

Similar patterns are found in studies on bereaved siblings of children with cancer. In a qualitative study 10 on siblings losing a brother or sister to cancer, emotional problems expressed by the siblings were loneliness, anxiety, anger and jealousy. Moreover, Martinson and Campos 19 interviewed adolescents 7–9 years after the loss of a brother or sister to cancer, and the majority of the siblings thought that the death of the siblings had increased their personal or family growth. It was also reported that 16% of the siblings had not worked through their grief 7–9 years after the death. Birenbaum 20 assessed behaviour problems in children and adolescents up to 1 year after they had lost a sibling to cancer and reported that the bereaved children and adolescents had more behavioural problems than the normative sample. There was also an apparent age difference in the types of symptoms. Adolescents appeared to be more at risk than the younger children.

The emotional problems observed in siblings who have lost a brother or sister to cancer seem to start already during the illness of the dying child. Siblings of children living with cancer have been observed to suffer characteristic patterns of psychological distress 21, 22. Studies have reported that the healthy siblings have more anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, and a poorer quality of life than the normal population 22. Positive effects have also been reported, such as a sense of increased family closeness 23 and increased personal maturity and growth 24-26.

Research on bereaved young adult siblings is sparse compared with research on other types of loss (e.g. death of parent or spouse), and existing research has focused on adolescents. The aims of this population-based nationwide study were to assess the prevalence of unresolved grief in bereaved young adults (19–33 years), 2–9 years after losing a brother or sister to cancer, and examine possible contributing factors, such as symptoms of anxiety and depression, and social support.

Methods

Participants

The Swedish Childhood Cancer Registry was used to identify children and adolescents who were diagnosed with a malignancy before the age of 17 years and died before the age of 25 years, between 2000 and 2007. Of a total of 545 children who had died of cancer, 187 were eligible for the study (Table 1). Study inclusion criteria for the siblings of the deceased were that they had to be born in one of the Nordic countries, be proficient in the Swedish language, have a listed phone number and address and be over 18 years at the time of the study. The siblings of the deceased were identified through the Swedish Population Registry. During the study period, 271 siblings were identified, and 240 of those fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

| 545 | Children (boys and girls) identified in the Swedish Childhood Cancer Registry who died between 2000 and 2007 |

| 189 | Children with siblings younger than 18 years at follow-up (2008) |

| 75 | Children with parents born outside the Nordic countries |

| 28 | Children born outside the Nordic countries |

| 23 | Children with no siblings |

| 13 | Children with siblings older than 25 years when the ill child died |

| 8 | Children ill less than a month |

| 8 | Children with siblings younger than 12 years when the ill child died |

| 6 | Children with siblings that were deceased |

| 4 | Children were adopted |

| 3 | Children with unknown personal data in the registry |

| 1 | Child diagnosed with cancer but died from other causes |

| 358 | Total number of excluded children |

| 187 | Total number of eligible children |

Questionnaire development

A study-specific questionnaire was developed using a method similar to Charlton's approach 27 and utilised in more than 20 projects in the Division of Clinical Cancer Epidemiology 28-31. On the basis of a literature review, consultation with experts in the field of paediatric oncology and interviews with eight bereaved siblings, hypotheses and study-specific questions were generated. The questions and response alternatives were then tested on another group of eight bereaved siblings to assess whether the questions were clear and correctly understood as intended by the investigators. Two pilot studies were then conducted. Twenty-nine bereaved young people who lost a brother or sister to cancer between the years 1991 and 2004 (4–17 years earlier), as well as 50 matched non-bereaved siblings from the general population, were contacted for the first pilot study. Bereaved siblings were identified as described earlier, whereas the non-bereaved siblings were matched with a deceased child for age, gender and place of residence and traced through the Swedish Population Register. Because of a low response rate (55% for the bereaved and 50% for the non-bereaved siblings), a second pilot study was conducted. To improve the participation rate, years since loss was decreased to 2–7 years earlier (limiting it to 2001–2006). In the second pilot study, we also changed the methodology for recruiting non-bereaved siblings to include a personal phone call prior to sending out the questionnaire, which had been routinely carried out for the bereaved siblings. Seventeen bereaved and 25 matched non-bereaved siblings from the general population were contacted for this second pilot study. The response rate was much better in the second pilot; 82% of the bereaved and 83% of the non-bereaved siblings participated. The questionnaire was revised before the nationwide study was conducted.

Procedure

All eligible siblings received a letter describing the study and an invitation to participate. In families with more than one sibling eligible, all siblings were invited. Approximately 1 week later, they were contacted by telephone and asked if they would consent to participate in the study. Those who gave consent were sent a study-specific questionnaire together with a separate reply card; to maintain the anonymity of the participants, the questionnaire was unidentifiable. About 3 weeks after the questionnaire was sent out, a combined thank you and reminder card was mailed. Those who had not returned their reply card within a few weeks received a reminder by telephone. The study was approved by the Karolinska Institute Regional Ethics Committee.

Measures

The study-specific questionnaire contains 200 items covering sociodemographics, current psychological health, and family-related and healthcare-related factors relating to the brother or sister's illness and death. The present study included the following variables.

Grief

The present study focused on siblings' resolution of grief with one simple question: ‘Do you think you have worked through your grief over your sibling's death?’ The response alternatives were as follows: ‘Not applicable, I was too young’, ‘No, not at all’, ‘Yes, to some extent’, ‘Yes, a lot’ or ‘Yes, completely’. Siblings who responded ‘Not applicable’ were excluded from the analysis.

To assess for the validity of this primary question, three questions adopted from the Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG [32]) were included: ‘Have you in the last month felt strongly that you are longing for your brother or sister?’ ‘Have you in the last month felt that you cannot trust people?’ and ‘Have you in the last month felt that life is empty without your brother or sister who died of cancer?’ The response alternatives were as follows: ‘Never’, ‘Yes, sometimes’, ‘Yes, regularly’, ‘Yes, most days’ and ‘Yes, every day’.

Descriptive and sociodemographic characteristics

Several other characteristics that were regarded as possible contributing factors to the main outcome were included in the analyses. The variables included in the study were as follows: time since loss, age at the time of the study, age at the death of brother or sister, gender, living with partner, living with parents, employed (yes/no), studying (yes/no), educational level (started and finished), dependent children (yes/no), loss of other significant person before the death of brother or sister, and loss of other significant person after the death of brother or sister.

Anxiety and depression

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale 33 (HADS) was used to assess symptoms of general anxiety and depression. The HADS consists of two subscales, anxiety and depression, with seven items each. Each item is rated on a scale of 0 to 3, where 0 equals no symptom and 3 equals severe symptom. The HADS is used extensively in health care and has been psychometrically evaluated in several clinical populations.

Social support

One question regarding siblings' need for social support was included in this present study: ‘In general, to what extent did your need for social support get satisfied in the past year?’ with five response alternatives ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘completely’.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed by using IBM spss version 21 for Windows (Armonk, New York). Pearson correlations were used to assess the associations between worked through grief and the sum of the questions adapted from the ICG as a measure of validity. Bivariate regression analyses were used to assess the associations between worked through grief and independent variables. Variables obtaining a p-value of <0.10 in bivariate regressions were considered for inclusion in multiple regression analyses (enter model) with worked through grief as dependent variable. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 for acceptance in the enter model.

Results

Participants

Of the 240 possible participants, 174 (73%) responded to the questionnaire, 20 declined participation and 46 did not respond to the questionnaire after receiving it. As participation was completely anonymous, differences between the responders and the non-responders could not be examined.

Of the responders, 101 (58%) were female and 73 (42%) were male. The participants were between 12 and 25 years of age (mean = 17.7, SD = 3.7) at the time of death of their brother or sister. The majority of siblings were between 19 and 23 years (mean = 24.0, SD = 3.8, range 19–33) at the time of investigation. The average time since loss was 6.3 years (range 2–9, SD = 2.3). Twenty-nine of the participants stated that they had one or more dependent children. Sociodemographic data are presented in Table 2.

| Characteristics | Bereaved siblings | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | % | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 101 | 58 |

| Male | 73 | 42 |

| Age, years | ||

| 19–23 | 88 | 51 |

| 24–28 | 59 | 34 |

| 29–33 | 26 | 15 |

| Not stated | 1 | <1 |

| Birth order | ||

| Youngest | 23 | 13 |

| Middle child | 70 | 40 |

| Eldest | 80 | 46 |

| Not stated | 1 | <1 |

| Relationship to brother or sister | ||

| Share the same parents | 144 | 83 |

| Share one parent | 30 | 17 |

| No. of full siblings | ||

| 1 sibling (the deceased) | 52 | 30 |

| >1 siblings | 102 | 59 |

| Not stated | 20 | 12 |

| No. of half siblings | ||

| 1 sibling (the deceased) | 12 | 7 |

| >1 siblings | 38 | 22 |

| Living arrangements | ||

| Living with parents | 49 | 28 |

| Living with partner | 74 | 43 |

| Living with friend | 4 | 2 |

| Live alone | 46 | 26 |

| Not stated | 1 | < 1 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 75 | 43 |

| Unemployed | 12 | 7 |

| Student | 66 | 38 |

| Other | 19 | 11 |

| Not stated | 2 | 1 |

| Level of started education | ||

| Elementary school | 4 | 2 |

| Upper secondary school | 104 | 60 |

| University | 66 | 38 |

Grief

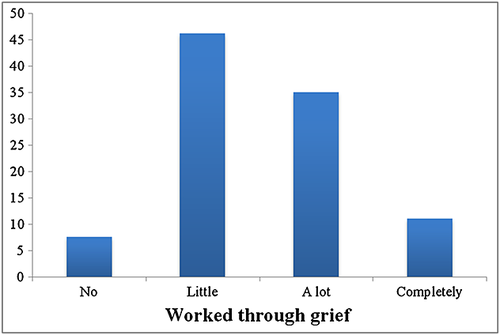

Thirteen (7%) of 174 bereaved siblings reported that they had not worked through their grief at all, and 79 (45%) reported that they had worked through their grief to some extent. Sixty (34%) of the siblings stated having worked through their grief a great deal, and 19 (11%) stated having completely worked through their grief (Figure 1). One (<1%) sibling did not answer the question, and two (1%) siblings answered ‘Not applicable, I was too young’.

Worked through grief correlated strongly with the questions from the ICG questionnaire (r = −0.51, p < 0.001). The correlation was in the expected direction, that is, lower scores on the ICG questions were associated with worked through grief.

Association between worked through grief and proposed contributing factors

As expected, longer time since loss was associated with having worked through grief to a greater extent. Living with a partner and having one's needs of social support satisfied were associated with more completely worked through grief, as were lower symptoms of anxiety and depression at time of study (Table 3).

| Independent variables | Bivariate regressions | Multiple regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | |

| Time since loss | 0.30 | <0.001 | 0.22 | 0.005 |

| Age at investigation | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.83 |

| Age at loss | −0.025 | 0.76 | ||

| Gender, female = 0/male = 1 | 0.09 | 0.27 | ||

| Living with partner, no = 0/yes = 1 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.59 |

| Living with parents, no = 0/yes = 1 | −0.10 | 0.21 | ||

| Employed, no = 0/yes = 1 | −0.08 | 0.33 | ||

| Studying, no = 0/yes = 1 | −0.03 | 0.69 | ||

| Education started, 0 = low/1 = higha | 0.05 | 0.53 | ||

| Education finished 0 = low/1 = higha | 0.089 | 0.25 | ||

| Anxiety (HADS) | −0.27 | <0.001 | −0.01 | 0.93 |

| Depression (HADS) | −0.31 | <0.001 | −0.19 | 0.08 |

| Social support | 0.37 | <0.001 | 0.26 | 0.002 |

| Dependent children, no = 0/yes = 1 | 0.07 | 0.36 | ||

| Lost other significant person prior to sibling, no = 0/yes = 1 | −0.11 | 0.16 | ||

| Lost other significant person after sibling died, no = 0/yes = 1 | −0.09 | 0.27 | ||

| F-value | 8.15 | <0.001 | ||

| R2 | 0.24 | |||

| Adj R2 | 0.21 | |||

- Variables included in the multiple regression are in bold.

- HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

- a Low + medium versus high education.

The following independent variables were not found to be statistically significantly associated with bereavement outcome: the sibling's age at the time of loss, gender, living with parents, having dependent children, being employed, studying, level of education started, level of education finished and loss of another significant person prior to or after the sibling's death (Table 3).

Contributing factors to having worked through grief

The results from the multiple regression analyses are shown in Table 3. Twenty-one percent of the variance (adjusted R2) was explained by six independent variables in the enter model, but only two made statistically significant contributions: time since loss and social support. Worked through grief was associated with less symptom of depression at the time of survey, but it was only marginally significant (p = 0.08). Worked through grief was associated with longer time since loss and need of social support being satisfied to a greater extent.

Discussion

The results suggest that even 2–9 years after the loss of a sibling to cancer, more than half of the bereaved young adults had not worked through their grief.

This may be an indication that young adult sibling's grieving process is prolonged. The sibling bond is thought to be one of the most important in one's lives 34, 35, and thus, it may be difficult to come to terms with the loss of a brother or sister, especially during the vulnerable time of being a teenager or young adult.

In the present study, 7% of the siblings reported that they had not worked through their grief at all, which corresponds to the prevalence rate of prolonged grief disorder in a community-based sample in the USA, reported by Prigerson et al.[36]. Our results showed that worked through grief correlated strongly with the questions adapted from the ICG, suggesting that the single-item question assessing grief may be a reasonable indicator of prolonged grief. Prolonged grief has been linked with higher risks of psychological, physical and social problems than in the bereaved population in general 37, 38.

The strongest contributing factor to the explained variance of worked through grief was perceived social support. This is in line with the previous research suggesting that social support is important during bereavement. Research has shown that lack of social support is a risk factor for negative bereavement outcome 39. Nolbris and Hellström 10 reported that siblings expressed social support from friends and school as being important after losing a brother or sister to cancer 1.5–6 years earlier. In another study 40, bereaved adolescent siblings reported that positive social support, such as ‘people being there for me’, was helpful in the grieving process. A study on siblings of children with cancer found that siblings who reported having more social support had less anxiety and fewer behaviour problems than siblings reporting lower social support 41.

Depression is thought to be a common reaction after bereavement 42. The differences and similarities between depression and grief have been studied 43-46, and researchers suggest that they represent distinct, although related, reactions to bereavement 43, 46. The present study showed that higher levels of depression were associated with unresolved grief; however, it was not statistically significant in the multiple regression analysis. This may suggest that the symptoms of depression are part of their ongoing grieving process. A recent study 47 on bereaved young adults, including seven siblings, showed that many of the individuals with complicated grief also had symptoms of depression, which is in agreement with our results.

The present study's primary research question has previously been posed to parents who had lost a child to cancer 4 –9 years earlier 48, 49. Those two studies found that 26% of the parents had not worked through their grief, and they were more likely to report symptoms of anxiety and depression than parents who had resolved their grief 4–9 years after the loss 49. Kreicbergs et al. also reported that social support facilitated the grieving process 48.

It may be considered a limitation to ask siblings to assess their grief status with a single question, rather than using standardised scales. However, it can also be regarded as a strength that in a simple way ask siblings to assess their own grief status. The face validation of this item showed that the siblings understood the question as the investigators intended. In the development of the questionnaire, the questionnaire was tested on siblings who had lost a brother or sister to cancer, and an investigator was present to assess whether the questions were interpreted and understood as intended. The same process was conducted in the study 48, 49 on parents who had lost a child to cancer. Moreover, it correlated with the questions adopted from ICG.

Another limitation is that social support was only measured with one item. Although the study-specific questionnaire includes several questions regarding social support, it is out of scope of the present manuscript and will be presented elsewhere.

The use of siblings' self-report, rather than the parent report that is often seen in studies of bereaved siblings, is a strength of the present study. Another strength is the high response rate. The wide range of siblings' age and time since loss can be considered a limitation. However, it can be argued that it makes the results more generalisable. A definite strength of the study is that it uses a nationwide sample, which can therefore be considered representative of the Swedish population and populations of other countries with comparable social standards.

Taken together, the results from this study and the two other studies 48, 49 that posed the same single-item question to parents who had lost a child to cancer suggests that this simple question can be useful in clinical practice to find out how siblings and parents are doing after bereavement and detect significant complications. It could be used during follow-up of bereaved family members, where it could be easily administrated and answered.

A clinical implication of this study is that healthcare professionals and family members should be informed that the sometimes forgotten bereaved siblings may grieve for several years after the loss. They should also be informed of the significance of social support after the loss of a sibling and should be encouraged to support the siblings. Effective interventions to support this group of bereaved siblings are warranted. In future studies, we may search for care-related factors predicting unresolved grief.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Childhood Cancer Foundation, the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Society, Karolinska Institute and Sophiahemmet University College. The funding bodies had no involvement in any part of the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.