Social support and quality of life among lung cancer patients: a systematic review

Abstract

Objective

This systematic review analyzed the relationships between social support and quality of life (QOL) indicators among lung cancer patients. In particular, the patterns of relationships between different social support facets and sources (received and perceived support from healthcare professionals, family, and friends) and QOL aspects (emotional, physical symptoms, functional, and social) as well as the global QOL index were investigated.

Methods

The review yielded 14 original studies (57% applying cross-sectional designs) analyzing data from a total of 2759 patients.

Results

Regarding healthcare professionals as support source, corroborating evidence was found for associations between received support (as well as need for and satisfaction with received support) and all aspects of QOL, except for social ones. Overall, significant relations between support from healthcare personnel and QOL were observed more frequently (67% of analyzed associations), compared with support from families and friends (53% of analyzed associations). Corroborating evidence was found for the associations between perceived and received support from family and friends and emotional aspects of QOL. Research investigating perceived social support from unspecified sources indicated few significant relationships (25% of analyzed associations) and only for the global QOL index.

Conclusions

Quantitative and qualitative differences in the associations between social support and QOL are observed, depending on the source and type of support. Psychosocial interventions may aim at enabling provision of social support from healthcare personnel in order to promote emotional, functional, and physical QOL among lung cancer patients.

Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Introduction

Quality of life (QOL) among cancer patients is assumed to be multidimensional and account for at least four aspects, such as physical (or physical symptom-related), social, functional, and emotional (or psychological), as well as the global (or general) index referring to the overall QOL evaluation 1. QOL is usually considered a secondary outcome in evaluating treatment for non-small-cell lung cancer and small-cell lung cancer patients, with overall survival constituting primary outcome 2. However, QOL of lung cancer patients has an increasing clinical relevance. Among the trials showing no effect of applied treatment on overall survival, 50% indicated significant positive/negative effects on QOL of lung cancer patients 2.

Social support is a complex, multi-facet construct 3. Perceived social support deals with perceptions concerning the general availability of support 4, 5. In contrast, received support refers to evaluations of recalled actual acts of supportive behaviors, whereas satisfaction with received support would refer to patient's evaluations of specific behaviors recalled as acts of support 4, 5. Overall, perceived and received support may be seen as theoretically distinct and moderately associated 4, 5. Another facet of support, called need for support, deals with evaluations of the degree of need for mastering challenges with actual acts of help from others 5. Received support, need for support, and satisfaction with received support are conceptually related, as they refer to actual acts of support 5.

Theories of social support classify this construct depending on its function and distinguish emotional (e.g., empathy, understanding), informational (e.g., advice about making decision), or instrumental (e.g., physical assistance) support 4, 5. In general, social support deals with the function and quality of social relations 5. In contrast, social integration (e.g., the size of social network) refers to the structure and the quantity of social relations 5. Other constructs, such as marital satisfaction are usually seen as the outcomes of perceived or received support 3. Although all these social concepts may relate to QOL, the underlying mechanisms would differ 5, 6, and thus, social support, social integration, and satisfaction with relationships should be treated as distinct variables.

In the model linking support to health proposed by Uchino 3, social support is assumed to promote QOL, affect, and morbidity through two psychosocial mediating mechanisms: behavioral processes (e.g., fostering health-promoting behaviors, adherence) and psychological processes (e.g., stress appraisal) 3, 7. Those mechanisms affect immune and cardiovascular functions, which in turn influence disease progression and QOL 3.

Research explaining morbidity, mortality, and QOL among cancer patients often concentrates on support from family and friends 3, 6, 8. On the other hand, most recent studies dealing with lung cancer patients highlight the role of support from healthcare professionals 9. Trials evaluating nurse-delivered interventions aiming at attenuating distress or physical symptoms among lung cancer patients indicated that such interventions may be an effective tool in promoting QOL. Patients assign high value to informational and emotional support from medical personnel, similar to the value of support from family and friends 10. Comprehensive analyses of the relationships among support and QOL among cancer patients should account for various support sources.

Optimal matching hypotheses suggests that the strongest links between social support and the outcomes are observed if there is a match between the type of support, characteristics of the stressor encountered, and the health outcomes 11, 12. For instance, it can be assumed that different aspects of QOL may be associated with support from different sources. Among cancer patients, support from family and friends may be related in particular to emotional (or psychological) QOL 13, whereas support received from healthcare personnel may be particularly helpful in attenuating physical symptoms 9.

The associations between social support and health outcomes vary across the types of cancer 6. Further, the levels of QOL aspects differ across types of cancer, with functional limitations varying from 45% among lymphoma survivors to 89% in lung cancer survivors 14. Differences in levels of QOL and in strength of associations between QOL and social support indicate that social support–QOL relationships should be analyzed in a context of a specific type of cancer. Therefore, in line with previous systematic reviews evaluating psychosocial predictors of QOL among cancer patients 15, the present review focuses on the associations observed for one type of cancer. In particular, we investigated lung cancer, which is among the most common cancer among men, increasing in prevalence among women 16, causing functional limitations more frequently than several other types of cancer 14, and accounting for the largest number of cancer-related deaths in the European Union 16.

Although there is evidence for the relationships between social support and progression in specific types of cancer 6, the overarching synthesis of the relationships between social support and QOL in lung cancer is missing. The studies focusing on QOL and social support among lung cancer patients often used similar research strategies but indicated diverse conclusions. Systematic review strategies offer an option of evaluating the accumulating studies, and thus, a synthesis of overarching findings can be provided 17. In general, systematic reviews collate evidence fitting specific eligibility criteria and use systematic methods in order to minimize bias in data collection and analysis 17. The study aimed at summarizing the evidence for the relationships between social support variables and QOL among lung cancer patients and survivors. In particular, we investigated the role of different sources of social support (health professionals versus family and friends) in the context of different aspects of QOL (physical, emotional, functional, social, and global).

Method

Materials and search procedures

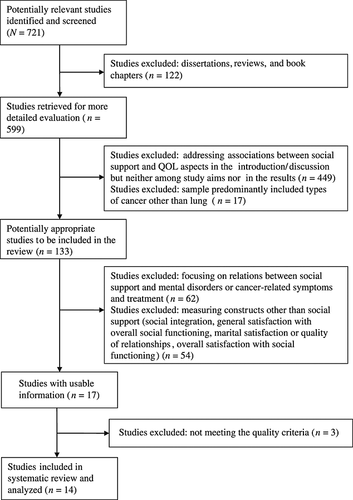

A systematic search of peer-reviewed papers published between January 1990 and November 2011 was conducted in PsycINFO, PsychArticles, Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition, Medline, and ScienceDirect. Three groups of key words, representing sample characteristics, and outcomes 17 were applied: (1) lung cancer, (2) social support, and (3) QOL. Manual searches of the reference lists were conducted. There was no language restriction. The initial search resulted in 721 papers (4% applying qualitative analysis). To minimize the possible bias, at least two reviewers (I .P., A. L., and R. C.) were involved at all stages of data extraction, quality appraisal, coding, synthesis, and analysis. The Cochrane systematic review methods were applied 17.

Inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, and data abstraction

Details of the selection process are presented in Figure 1. After the initial step, we selected publications that appeared in peer-reviewed journals (dissertations and book chapters were excluded). Original researches (reviews excluded) applying quantitative or qualitative methods, addressing the associations between social support and QOL among study aims and reporting respective results, were included. Papers analyzing data from lung cancer patients solely or analyzing lung cancer patients as the main study groups and papers featuring QOL outcomes following the broad WHO definition (physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environmental aspects) were included. Publications focusing solely on the presence of mental disorders or the intensity/number of cancer-related physical symptoms were excluded. Research on structural aspects of social relationships or social integration was not considered. Studies defining social support as general satisfaction with overall social functioning were excluded. At this stage, 17 studies meeting inclusion criteria were selected. Three studies that met less than 60% of quality criteria 18 and additionally failed to meet (at least partially) quality criteria referring to reporting participant selection, methods, findings (description of analyses or reports of some estimate of variance) were excluded as suggested in earlier research 19. In case of two papers discussing findings from the same study 20, 21, longitudinal findings were considered. Consequently, 14 studies were analyzed.

Descriptive data (including participant characteristics, methods, design, outcomes, and findings) were extracted and verified by two reviewers. Any disagreements in the processes of data selection and abstraction were resolved by a consensus method 17. Because of high heterogeneity of measures of social support and QOL, the application of meta-analysis was not possible.

Coding, quality assessment procedures, data synthesis, and analysis

Four broad categories of QOL were applied. Indices referring to the presence of physical symptoms (related and unrelated to lung cancer) and the presence of negative emotions or distress symptoms were respectively coded as physical and emotional aspects of QOL. Performance of and satisfaction with social roles (job, family tasks, etc.) and performance/satisfaction with daily functioning (e.g., ability to walk) were coded as social and functional aspects of QOL, respectively. Social support categories were applied using original categories (as proposed in analyzed research) of source (family and friends, medical personnel, spouse, closest person), functions (emotional, informational, or instrumental), and type (perceived, received, need for, satisfaction). The coefficients of concordance for categorizing variables were high (all Kappas ≥ .70, ps < .05).

In line with previous systematic reviews 22, 23, the following analytical strategy was applied: (1) data indicating whether the association between an index of social support and an index of QOL was significant were retrieved from the original studies and defined as ‘a unit of relationship’; (2) the unit was coded as ‘0’ if the association was not significant, ‘+’ if the association was significant and showing that higher support was related to better QOL, or ‘—’ if the association was significant and showing that higher support was related to poorer QOL.

The findings within one unit were then coded as indicating a significant relationship in the original study if significant associations between a social support index and at least 60% of QOL indices for its respective aspect showed such associations (e.g., significant associations were found between the support index and two out of three indices of the emotional aspect of QOL included in a study). The 60% threshold has been applied in earlier reviews 22, 23.

The results were summarized as showing corroborating evidence for the association between the index of support and QOL aspect if at least 60% of all original studies (addressing a respective support source) indicated significant associations between support and QOL indices (e.g., two out of three studies referring to support from family/friends and emotional QOL yielded positive findings). Again, the 60% threshold has been applied in earlier reviews 22, 23 as the indication of corroborating evidence. The results were summarized as showing preliminary evidence for the role of the social support index if (1) 50–59% of the studies discussing the social support variable and a respective outcome showed significant associations, or (2) the association was tested in only one study, which revealed significant effects 22, 23. To our knowledge, there is a lack of alternative thresholds used to analyze data in systematic reviews than those applied in the present study.

Quality assessment was conducted using the quality evaluation tool developed by Kmet et al. 18. Respective standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers 18 are included in several quality evaluation tools, such as TREND 24. The quality evaluation tool 18 applies quantitative methods, and it allows to investigate whether the study adheres to the following 14 criteria: sufficiently described objectives, evident/appropriate design, clear description of participant selection and measures, participant description, random allocation (experimental trials), blinding of interventionists (experimental trials), blinding of participants (experimental trials), selection of outcomes, appropriate sample size, analytic methods (selection and description), an estimate of variance reported in main results, controlling analyses for confounders, reporting results in sufficient detail, and conclusions supported by results. Each criterion is rated using a 3-point response scale. The summary scores (Table 1) are reported as percentages, representing a ratio of total score obtained to a total possible sum score 18. The concordance coefficients for quality assessment were high (all Kappas ≥ .76, ps < .01).

| Author, date | Methods: number and type of participants, study design; measurement point in relation to diagnosis or treatment | Quality scores 18 (quality criteria not met) | Aspects of QOL and number of indices included in the study, measures of QOL, social support categories | Resultsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived support from partner, the closest person, family members or friends | ||||

| Badr and Taylor 2008 25 | 158 NSCLC and SCLC patients; correlational, longitudinal (6-month follow-up); baseline—1 month within treatment initiation | 91 (9, 12) | QOL: emotional (one index) and social (one index); Brief Symptom Inventory and Dyadic Adjustment Scale; perceived emotional and instrumental support from partner | Significant effects of global support index on social QOL; no significant longitudinal effects on patients' emotional QOL |

| Jatoi et al. 2007 26 | 835 NSCLC patients; correlational, cross-sectional (a sub-sample of longitudinal study with 5898 patients); any point of illness trajectory from diagnosis to post-treatment | 100 | QOL: physical (seven indices), emotional/spiritual (one index), social (one index); Linear Analogue Self-Assessment and Lung Cancer Symptom Scale; perceived emotional and instrumental support from family or friends | Support from family and friends co-occurred with higher spiritual/emotional QOL (one index) and only one out of seven indices of physical QOL (married/widowed patients) |

| Esbensen et al. 2004 27 | 101 patients with different cancer sites, including NSCLC and SCLC older (65+) patients; correlational, cross-sectional; within 3 weeks after diagnosis | 86 (9, 11, 12) | QOL: physical (one index), functional (one index), and global (one index); EORTS-QLQ-C30; perceived emotional, instrumental, and informational support from family or friends | Instrumental support from adult children was related to physical aspect of QOL, a lack of other significant associations |

| Steele et al. 2005 28 | 129 home-based hospice palliative care patients with different cancer sites, including NSCLC and SCLC patients, palliative care patients; cross-sectional, correlational | 91 (9, 12) | QOL: physical (one index), emotional (one index), functional (one index); QOL; Missoula-Vitas Quality of Life Index; perceived instrumental, emotional and informational and support from family or friends | Social support from family and friends was related to better physical (one index), functional (one index), and emotional (one index) QOL |

| Received support from partner, the closest person, family members or friends | ||||

| Boehmer et al. 2007 13 | 175 patients with different cancer sites, including NSCLC and SCLC patients; correlational, longitudinal (6-month follow-up); baseline—1 week before surgery | 91 (9, 12) | QOL: physical (one index), emotional (one index), and social (one index); EORTC-QLQ-C30; received emotional, instrumental, and satisfaction with support from the closest person | Global index of support predicted emotional aspect of QOL; effects on physical and social QOL aspects non-significant |

| Porter et al. 2011 29 | 233 NSCLC and SCLC patients; CT: non-professional caregiver assisted education/social support intervention versus control group with coping/relaxation intervention; 4-month follow-up; baseline: early stage (I–III), patients from time directly after diagnosis to post-treatment | 91 (5, 12) | QOL: physical (three indices), emotional (three indices), functional (one index), and social (one index); Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Lung Cancer: FACT-L; received emotional and instrumental support from caregiver (family or friend member) | Significant effects of the intervention on emotional (two indices) and functional (one index) aspects of QOL, in particular among Stage I patients |

| Social support from healthcare personnel: received support, satisfaction form support received and need for support | ||||

| Bredin et al. 1999 30 | 233 NSCLC, SCLC, and mesothelioma patients; CT, nurse-assisted intervention targeting instrumental and emotional support; 8-week follow-up; after completing first line treatment | 82 (6, 7, 9, 12, 13) | QOL: physical (four indices), emotional (three indices), functional (three indices), and global (one index); WHO performance status scale, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Rotterdam Symptom Checklist (RSCL); received emotional and instrumental support from nurses | Intervention resulted in significantly larger (or a trend for) improvements in two emotional, three physical, and three functional indices of QOL |

| Wong and Fielding 2008 31 | 334 NSCLC and SCLC patients (combined with 253 liver cancer); correlational, longitudinal; 6-month follow-up; after primary surgical treatment | 100 | Global index of QOL (combining physical, emotional, functional, and social aspects); FACT-L; satisfaction with instrumental, informational, and emotional support from any medical personnel | Global index of QOL was predicted by instrumental support |

| Sanders et al. 2010 32 | 109 NSCLC and SCLC patients, correlational, cross-sectional; 6 within months since diagnosis | 91 (9, 4) | QOL: physical (one index) and emotional (three indices); Impact of Events Scale, Center for Epidemiologic Survey Depression Scale (CES-D), Distress Thermometer, Short Form-36; need for emotional, informational, and practical support | Higher need for support related to poorer emotional QOL (three indices) and lower physical QOL (one index) |

| Liao et al. 2011 33 | 152 NSCLC and SCLC patients, correlational, cross-sectional; data collected at 15 months (average) after diagnosis | 82 (9, 10, 12, 13) | QOL: physical (one index) and emotional (two indices); HADS, 21 Symptom List; need for receiving emotional, informational, and practical support | Higher need for support receipt was related to poorer emotional QOL (one index) but unrelated physical QOL |

| Perceived social support from any source (without indicating the source) | ||||

| Downe-Wamboldt et al. 2006 34 | 85 NSCLC cancer patients; correlational, cross-sectional; within 6 months of diagnosis | 91 (9, 12) | Global QOL (one index; combining physical, emotional, functional, and social aspects); Quality of Life Index—Cancer Version; perceived emotional, informational, and instrumental support | Global QOL was unrelated to perceived support |

| Henoch et al. 2007 20 | 105 NSCLC, SCLC, and metastases patients; correlational, longitudinal, 12-month follow-up; patients in palliative care; 2–142 months since diagnosis | 86 (9, 10,11) | Global QOL index (one index; combining physical, emotional, functional, and social aspects); Assessment Quality of Life at the End of Life; perceived emotional, informational, and instrumental support | Total index of social support predicted global QOL index at 6- and 12-month follow-ups |

| Naughton et al. 2002 35 | 70 SCLC patients; correlational, cross-sectional (for analysis of QOL–support associations); time since diagnosis not provided | 91 (9, 9) | QOL: physical (10 indices), emotional, (one index), functional (one index), and social (two indices) and global (one index); EORTC-QLQ-30; CES-D, perceived emotional, informational, and instrumental support | Social support (general index) was related to better physical (two indices) and higher global QOL but unrelated to other QOL indices |

| Arbatt and Viljoen 1994 36 | 40 patients with lung cancer (mixed) patients, correlational, cross-sectional; attending follow-up clinic | 64 (2, 3, 4, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) | QOL: emotional (two indices) and global (two indices); HADS, RSCL, Outlook, the Spitzer QL-index; perceived emotional support | Perceived support was associated only with one index of emotional QOL aspect |

| Need for social support from any source (without indicating the source) | ||||

| Downe-Wamboldt et al. 2006 34 | For details, see above | For details, see above | QOL: for details, see above; and need for support | Global QOL was correlated with lower levels of need for social support |

- NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; SCLC, small-cell lung cancer; CT, controlled trial; EORTC, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; QLQ, Quality of Life Questionnaire.

- Quality criteria (Kmet et al. 18): 2, study design evident/appropriate; 3, participant selection/measures characteristics; 4, participant characteristic; 5, random allocation (CTs); 6, blinding of interventionists (CTs); 7, blinding of participants (CTs); 9, sample size appropriate; 10, analytic methods; 11, estimate of variance reported in main results; 12, analyses controlled for confounding; 13, reports in sufficient detail.

- a Higher support associated with better QOL, unless indicated otherwise.

The cut-off score for the acceptable quality of studies was twofold: (1) quality score ≥ 60% (55% and 60% are suggested as relatively liberal thresholds, indicating acceptable quality 18) and (2) the study should at least partially meet the criteria referring to the methods, analyses, and results 19. Meeting at least 75% of quality criteria is considered a conservative quality threshold 18, indicating minor flaws 19 and thus showing relatively high quality.

In case of longitudinal studies, data from the latest available follow-up were included into analysis. For experimental studies investigating the influence of a social support intervention, the effect of the manipulation was accounted for in our analyses. In case of multiple analyses dealing with the same QOL and support indices reported in the original study, we included units that controlled for potential confounders.

Results

Description of analyzed material

Reviewed research fell into three categories, differing in source and type of support: support from family and friends (43%, n = 6), support from healthcare personnel (29%, n = 4), support from any available source (29%, n = 4). Except for one study, at least two functions of social support (emotional and instrumental) were measured, but these functions were combined in most cases (93%, n = 13 studies); therefore, one global index of support including different functions was applied in the present research. Included studies varied in terms of the QOL indices: 71% (n = 10) accounted for the emotional aspect of QOL, 71% (n = 10) included a physical aspect, a social aspect was addressed in 36% (n = 5), a functional aspect was addressed in 36% (n = 5), and a global index was included in 50% of studies (n = 7). Three studies (21%) investigated only a global QOL index (Table 1).

Data from 2759 patients were analyzed. Sample size ranged from 40 to 835 (M = 197.07, SD = 199.19). A total of 35 support–QOL units of relationship were analyzed in original trials. In 17 support–QOL units of relationship (49%), significant associations were found (QOL aspects: emotional, 66%; functional, 60%; global index, 67%, physical, 40%; social, 25%). The scores of the quality evaluation tool 18 ranged from 64 to 100 (M = 88.36, SD = 8.79). Overall, 13 studies showed minor flaws, and thus, they are of relatively high quality (meeting above 75% of quality criteria) (Table 1). However, only 14% of studies were experimental, 29% had a longitudinal correlational design, and 57% used a cross-sectional design (Table 1).

Relationships between quality of life and social support from family and friends

A total of 53% of analyzed relationships showed significant associations between support and QOL aspects. Research investigating the role of perceived support from family and friends provided corroborating evidence for positive associations between perceived support and emotional (two in three studies) and physical (two in three studies; 66%) aspects of QOL (Table 2). Research providing corroborating evidence was of relatively high quality but mostly of a cross-sectional character (Table 2).

| Social support source and the facet of support | Associations between social support and aspects of QOL | Conclusions: corroborative evidence (at least 60% of analyzed relationships were significant) was obtained for: | Quality of corroborative evidence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Emotional | Functional | Social | Global index | |||

| Family and friends: perceived support | +, +, 0 | +, +, 0 | +, 0 | +, 0 | 0 | Associations between perceived social support from family and friends and emotional and physical aspects of QOL | Relatively high quality |

| Family and friends: received support | 0, 0 | +, + | + | 0 | Associations between received social support from family and friends and emotional aspect of QOL. A lack of associations between support and physical aspects of QOL | Relatively high quality | |

| Healthcare personnel: received support, satisfaction with support receipt and need for support | +, +, 0 | +, +, 0 | + | +, 0 | Associations between social support from healthcare personnel and QOL aspects: physical and emotional | Relatively high quality | |

| Perceived support from unspecified source | 0, 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | +, +, 0 | Associations between social support from unspecified sources and the global QOL index. A lack of significant association for physical symptoms and QOL | Relatively high quality for global QOL index. Mixed quality for physical aspect of QOL |

- A relatively high quality of studies was defined as meeting more than 75% of quality criteria 18, 19, whereas a mixed quality was defined as meeting between 60% and 75% of quality criteria.

- +, significant associations between the index of social support and at least 60% of indices of the respective QOL aspect in the original trial; 0, a lack of significant associations or significant relationships between the index of social support and 59% (or less) indices of the respective QOL aspect in the original study.

It has to be noted that corroborative evidence for associations between perceived support from family/friends and physical aspect of QOL was found for specific, vulnerable subgroups (individuals aged 65 years or older or patients in palliative hospice care). Other research showing a lack of such relationship was conducted in general samples of patients.

Regarding received support from family and friends, corroborating evidence was found for relationships with the emotional aspect of QOL (two in two studies, 100%), but available research indicated a lack of associations between receipt of support from this source and the physical aspect of QOL (two in two studies, 100%). Research providing corroborating evidence was of relatively high quality and applying a longitudinal analysis (Table 2).

Relationships between quality of life and support from healthcare personnel

Overall, 67% of relationships analyzed in original studies yielded significant associations between social support from healthcare personnel and QOL aspects. Analyzed research dealt with received support, satisfaction with received support and need for support. As all three facets of support refer to the actual specific acts of support 4, 5, they were analyzed together. Corroborating evidence for the role of receipt/need for support from healthcare personnel was found for emotional (two in three studies; 67%) and physical QOL aspects (two in three studies; 67%). Preliminary evidence was found for functional (one in one study) and global QOL indices (one in two studies) (Table 2). High satisfaction with support receipt and high received support were related to better QOL (in all measured aspects), whereas patients reporting high (unsatisfied) need for support declared poorer QOL (lower emotional and physical functioning). Research providing corroborating evidence was of relatively high quality, but only two in four studies had a longitudinal design (Table 1).

Associations between quality of life and social support from different (unspecified) sources

Only 25% of relationships tested in original studies yielded significant results. Corroborating evidence for the role of perceived social support was found for the general QOL index (two in three studies; 66%). Corroborating studies were of relatively high quality, but only one had a longitudinal design (Table 2). For other aspects of QOL, a lack of significant relationships was observed (physical: none in two studies; emotional: none in one study; functional: none in one study; social: none in one study). Higher perceived support from unspecified sources was related to higher global QOL. Additionally, one study tested relationships between need for support and global QOL and thus showed preliminary evidence for such associations.

Discussion

The findings of our systematic review allow tentative conclusions to be drawn from evidence accumulated in original research on the associations between the QOL aspects and social support from family, friends, healthcare professionals, and other sources. Distinct patterns of findings were observed for different sources of social support. First, when support from friends and family or support from healthcare personnel was analyzed, a majority of the associations were significant. By contrast, a majority of research accounting for support from undistinguished sources yielded negligible support–QOL associations. Second, different aspects of QOL were associated with social support coming from different sources. In particular, both perceived support and received support from family or friends were associated with better emotional QOL. Additionally, we found corroborative evidence for associations between perceived support from family/friends and physical aspect of QOL, but no such associations emerged for support received from family/friends. There was no corroborating evidence (or preliminary evidence) for other aspects of QOL. We found consistent corroborating or preliminary evidence for the significant relationships between support from healthcare personnel (received support, satisfaction with support received, and need for support receipt) and several QOL aspects (emotional, physical, functional, global index). Finally, research analyzing the role of perceived social support from unspecified sources indicated a lack of relationships with emotional, physical, social, or functional aspects of QOL, but corroborating evidence was found for the association between perceived support and global QOL.

The majority of studies had a correlational design, and the causal order of the relationships between support and QOL cannot be established. Support from family may promote higher QOL (emotional aspect), but it is also possible that higher QOL (emotional aspect) of lung cancer patients results in receiving and perceiving more support from family (e.g., with lower level of caregiver burnout as the mediating mechanism). Experimental research is needed to indicate the causal variables in support–QOL associations.

The results of our review are in line with the optimal matching hypothesis 11, 12, suggesting that the effects of social support are stronger when the outcomes match the measured social support. Recent research conducted among patients with a chronic health condition (HIV) showed a significant role of support from healthcare personnel for physical well-being and the role of support from family for emotional well-being 37. Similarly, we found that received support (or need for receiving support) from healthcare personnel seems to be more relevant for physical aspect of QOL among lung cancer patients, whereas the most consistent associations between perceived support and the emotional QOL aspect were found when friends and family were the source of support. These findings have implications for interventions promoting QOL among lung cancer patients. Effective interventions that aim at influencing all QOL aspects should use techniques that enable provision of support from various sources, such as family, friends, and healthcare personnel. In line with previous experimental research 9, our study suggests the relevance of supportive/educational interventions delivered by nurses, in particular for promoting better physical QOL. Such interventions may be of particular importance as targeting physical aspects of QOL in interventions may result in changes of QOL in its emotional or social domains 38.

The present systematic review suggests that the role of perceived support from family may be different when lung cancer patients who were recently diagnosed are compared with more vulnerable groups, such as older or palliative care patients with lung cancer 39. We found that among vulnerable patients, physical QOL was associated with perceived family support, whereas such associations were not found for the general sample. Although further research is needed, the findings have implications for interventions promoting QOL among lung cancer patients who are older or in palliative care. Helping families to develop skills necessary for support provision may affect causal (symptom-related) indicators of QOL, which in turn may promote better QOL across its indices 39. Earlier research highlighted a need for interventions enabling family support provision for lung cancer patients 40. Our study suggests that such interventions may be particularly needed for families of vulnerable lung cancer patients.

This systematic review has limitations. The majority of studies applied cross-sectional designs; therefore, no causal conclusions or conclusions about predictive direction can be drawn. Previous research on social support among cancer patients suggests substantial gender differences 41. The interplay between gender, source, and type of support may be highly important but could not be addressed in this review, as most of original research did not account for gender as a potential moderator. We used a broad definition of QOL, which allowed for an inclusion of studies measuring QOL aspects with different instruments, not only those originally designed to tap cancer patients' QOL. This liberal approach resulted in applying various measures, in particular in evaluations of the emotional aspect of QOL. Assessment issues limit the conclusions. Although the definition of levels of corroborating evidence and preliminary evidence was based on those applied in previous reviews 22, 23, the applied thresholds are rather arbitrary. Nonetheless, because of its application in several systematic reviews, comparisons across reviews are possible. Future research should propose theory- and evidence-based thresholds for analyzing data accumulated in systematic reviews. In order to obtain more precise description of social support, future studies need to account for social constraints related to negative support. Three studies analyzed data from patients with lung and other primary cancer sites; therefore, the results should be treated with caution. Further, research dealing with long-term survivors or focusing on specific stages of cancer (and their moderating role) are missing.

In spite of these limitations, the present study provides an insight into the relationships between social support from different sources and QOL among lung cancer patients. Corroborating evidence was found for associations between patients' perceptions of supportive acts by healthcare personnel (in particular, received support, satisfaction with received support, and need for support) and physical and emotional QOL aspects. Support from healthcare personnel was related to the broadest scope of QOL indicators, and significant relations were observed more frequently than when support from families/friends was analyzed. Perceived support and received support from family/friends were related to emotional QOL. Although further research is needed, family support may play a different role among vulnerable patients, as it is foremost related to their physical QOL.

Acknowledgements

The contribution of A. Luszczynska was supported by BST/WROC/2013 grant and the Foundation for Polish Science. The study was partially supported by a grant 1395/B/H03/2009/37 from the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education awarded to R. Cieslak.