Factors reported to influence fear of recurrence in cancer patients: a systematic review

Abstract

Objective

Fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) is a significant psychological problem for cancer survivors. Some survivors experience FCR, which is both persistent and highly distressing. The aim of this systematic review was to identify the key factors associated with fear of recurrence among cancer patients.

Methods

A comprehensive literature search using keywords was performed with three databases, followed by an organic search to identify additional relevant articles. Included studies had a quantitative methodology presenting empirical findings focussed on adult cancer patients. A methodological quality assessment was performed for each study, and the strength of evidence was defined by the consistency of results.

Results

Forty-three studies met the inclusion criteria and are presented in this review. The most consistent predictor of elevated FCR was younger age. There was strong evidence for an association between physical symptoms and fear of cancer recurrence. Additional factors moderately associated with increased FCR included treatment type, low optimism, family stressors and fewer significant others. Inconsistent evidence was found for socio-demographic factors.

Conclusions

Fear of cancer recurrence is a complex issue influenced by a multitude of factors, including demographic, clinical and psychological factors. However, some studies have reported contradictory evidence, and FCR has been measured using a range of scales, which can hamper comparison across studies. Further research is needed to clarify inconsistencies in the current published research. Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Introduction

Advances in the early detection and treatment of cancer have resulted in improved survival rates and an increasing cohort of cancer survivors 1. Most patients do well following treatment; however, some cancer survivors experience negative emotional outcomes 2. Anxiety and depression are more common among cancer patients than among the general population with prevalence rates of up to 65% reported 3. A significant emotional difficulty facing cancer survivors is fear regarding disease recurrence or spread 4. This is termed fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) 5 and is defined as the fear or worry that cancer will return, progress or metastasise 5, 6. FCR is prevalent with estimates of between 22% and 99% of cancer survivors experiencing FCR 5 and is considered one of the most distressing consequences of cancer 5. FCR can be long term and may predict poorer quality-of-life outcomes up to 6 years post-diagnosis 7.

A diagnosis of cancer, regardless of the patient's gender or age, brings psychological sequelae, including feelings of vulnerability, a sense of loss and concern for the future 7, 8. Therefore, FCR can be considered a normal and rational response to the threat of recurrence following cancer. However, in some cases, FCR may perpetuate dysfunctional behaviours including avoidance behaviour, hypervigilance for symptoms of recurrence 7 and an inability to plan for the future 9. In extreme cases, FCR has been associated with the development of anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress symptoms and depression 5, 10-12. Therefore, identifying patients who are at greater risk of experiencing FCR may improve patient management and inform interventions to reduce FCR. This review aimed to identify factors associated with FCR in cancer survivors.

Method

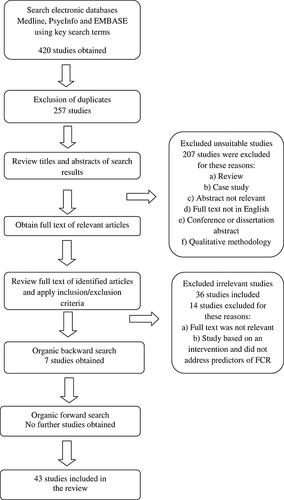

Three methods were used to identify relevant studies: a keyword search, a backward search and a forwards (citation) search (Figure 1). Literature searches were performed using three electronic databases: Medline (1948–August 2011), PsychINFO (1806–August 2011) and EMBASE (1980–August 2011). The search terms were cancer, cancer patients, oncology, cancer survivors, fear of progression, fear of recurrence, fear* about recurrence, concern* about recurrence. Terms relating to cancer were then combined using OR, as were terms relating to FCR. A further search was performed using the AND function. Duplicates were excluded. A backwards organic search was then performed, which involved hand searching the reference lists of included articles. A forwards (citation) search was then conducted.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) adult cancer patients with any tumour type; (ii) any stage of disease; (iii) being written in English; (iv) quantitative methodology; (v) presentation of empirical findings (i.e. not a review); and (vi) report of data on factors associated with FCR. Studies were excluded if they were published as a conference abstract or a case study. For each study, the following information was obtained: author, year of publication and demographic information (sample size, age, ethnicity, cancer type, measure of FCR, main findings).

Methodological quality assessment

Each article underwent quality assessment from a checklist of 11 items adapted from an established quality assessment tool 13. This process was undertaken independently by two researchers, a comparison was made and only minor differences emerged, which were resolved through consensus. The broad nature of the quality assessment allowed a range of methodologies to be assessed. Studies were scored depending on how fully they met each criterion (Table 1): 2—fully meeting the criterion; 1—partially meeting criteria; 0—not meeting the criteria. If a criterion was not applicable, then it was excluded from the score calculation. A total sum score was calculated by summing the number of ‘yes’ responses then multiplying this by 2 and adding this to the number of ‘partials’. The total possible sum was calculated as 22 minus 2 times the number of ‘n/a’. Finally, a summary score was calculated (total sum/total possible sum), reflecting the overall methodological quality. Studies were categorised as high quality (score of 17 or above), moderate quality (11 to 16) or low quality (10 or less).

| Study | Study design | Sample size, cancer type(s) | Time since diagnosis | Measures of FCR | Associated with greater FCR | Quality rating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northouse et al. 18, USA | Cross-sectional | 30, breast | Not stated | Fear of Recurrence Questionnaire | Fewer significant others | r = −0.39* | Mod |

| Fewer others understanding concerns | r = −0.40* | ||||||

| de Haes and Welvaart 23, Netherlands | RCT | 41, breast | 11 months post-surgery | Fear of Recurrence Checklist 58 | Younger age | r = −0.34* | Mod |

| Bartelink et al. 44, Netherlands | Cross-sectional | 172, breast | Not stated | Single item | Mastectomy versus BCT | 29% vs 13%* | Mod |

| de Haes et al. 41, Netherlands | RCT | 34, breast | 11 months post-surgery | Based on framework by Meyerowitz 58 | NA | — | Mod |

| Lasry and Margolese 39, Canada | RCT | 123, breast | 3.5 years post-surgery | Fear of Recurrence Index | Multiple surgeries | 8.2 vs 6.0** | Mod |

| Kemeny et al. 45, USA | Prospective | 52, breast | 18 months post-surgery | Psychosocial reactions to surgery 59 | Mastectomy versus BCT | 2.0 vs 1.3* | Mod |

| Lasry et al. 40, Canada | RCT | 123, breast | Not stated | Fear of Recurrence Index 39 | Chemotherapy | Full results missing* | Mod |

| Noguchi et al. 42, Japan | Cross-sectional | 90, breast | Not stated | Single item | NA | — | Mod |

| Curran et al. 22, UK | RCT | 278, breast | Not stated | Fear of Recurrence Scale 60 | Younger age | Full results missing** | High |

| Burnstein et al. 57, USA | Longitudinal (9-month follow-up) | 480, breast | Newly diagnosed | Fear of recurrence 38 | Use of psychological therapies | 8.17 vs 7.51** | High |

| Leake et al. 28, Australia | Cross-sectional | 202, gynaecological | 0–6 years | Functional Living Index 61 | Younger age | Mean age 49 vs 54* | High |

| Stanton et al. 16, USA | Longitudinal (12-month follow-up) | 70, breast | Not stated | Fear of Recurrence Questionnaire 18 | Younger age | r = −0.36** | High |

| Coping (avoidance oriented) | r = −0.33** | ||||||

| POMS distress | r = 0.60** | ||||||

| POMS vigour | r = −0.53** | ||||||

| de Haes et al. 43, UK, Netherlands, Greece, S. Africa | RCT | 136, breast | Not stated | Single item | NA | — | High |

| Härtl et al. 25, Germany | Prospective | 274, breast | 4.2 years | Single item | BCT versus mastectomy | 63.9 vs 55.3* | High |

| Younger age | <59 years* | ||||||

| Humphris et al. 17, UK | Prospective and cross-sectional | 87, orofacial | <2 years post-treatment | Single item | Younger age | χ2 = 9.31* | High |

| 100, orofacial | Anxiety | χ2 = 7.57** | |||||

| Mehta et al. 19, USA | Longitudinal (24-month follow-up) | 519, prostate | Not stated | Fear of Recurrence Scale 62 | Poorer quality of life | β = −0.23* | Mod |

| Poulakis et al. 38, Germany | Retrospective | 357, renal cell carcinoma | Not stated | Fear of Recurrence Scale 62 | Mandatory nephron-sparing surgery | 19.19 (CI 17.85 to 20.54)* | High |

| Larger tumour size | r2 = 0.8530** | ||||||

| Vickberg 6, USA | Cross-sectional | 169, breast | 3 years | Concerns about Recurrence Scale | BCT versus mastectomy | Mean difference = 9** | High |

| Younger age | Mean difference = 9** | ||||||

| Rabin et al. 36, USA | Longitudinal (4-month follow-up) | 69, breast | Not stated | Fear of Recurrence Scale 62 | Stage 2 vs 1 | F = 5.07** | High |

| Illness perceptions (timeline) | F = 9.69** | ||||||

| Gil et al. 31, USA | Longitudinal (10-month follow-up) | 244, breast | 6.8 years | Triggers of uncertainty | Hearing about another's cancer | Reported by 82% | High |

| New symptoms | 88% | ||||||

| Media Information | 63% | ||||||

| Annual check-up | 47% | ||||||

| Humphris and Rogers 55, UK | Longitudinal (12-month follow-up) | 87, head/neck | Not stated | Worry of Cancer Scale 59 | Smokers/relapsed versus quitters | F = 2.89* | High |

| Black and White 10, UK | Cross-sectional | 36, haematological | Not stated | Fear of Recurrence Questionnaire 18 | Low sense of coherence | F = 6.15* | Mod |

| Fear of Recurrence Scale 62 | |||||||

| Wade et al. 47, Australia | Longitudinal (12-week follow-up) | 44, breast | Not stated | Single item | Denial coping | r = 0.53** | High |

| Younger age | r = −0.34* | ||||||

| Breast cancer symptoms | r = 0.44** | ||||||

| Deimling et al. 32, USA | Cross-sectional | 321, breast, colorectal, prostate | 10.4 years | Cancer related | Race (African-American) | β = −0.22** | High |

| Health worries | Optimism | β = −0.27** | |||||

| Scale 63 | Symptoms | β = 0.20* | |||||

| Constanzo et al. 14, USA | Longitudinal (5-month follow-up) | 89, breast | Not stated | Concerns about Recurrence Scale 6 | Younger age | F = 9.90** | High |

| Lower education | F = 7.65** | ||||||

| Mastectomy | F = 6.45* | ||||||

| Kornblith et al. 24, USA | Longitudinal (12-month follow-up) | 252, breast, endometrial | Not stated | Fear of Recurrence Scale 62 | Younger age | F = 26.58** | High |

| Breast cancer | F = 17.48* | ||||||

| Mellon et al. 30, USA | Secondary analysis | 123, breast, colon, uterine, prostate | 3.4 years | Fear of Recurrence Questionnaire | Concurrent family stressors | r = 0.31** | High |

| Less positive meaning of illness | r = −0.43** | ||||||

| Co-morbidities | r = 0.35** | ||||||

| Somatic concerns | r = 0.19* | ||||||

| Steele et al. 34, UK | Cross-sectional | 100, colorectal | Not stated | Single item | Young children | 50% vs 22%* | High |

| Concern about results | Full results missing** | ||||||

| Bellizi et al. 21, USA | Longitudinal (12-month follow-up) | 730, prostate | Not stated | Fear of Cancer Recurrence Scale 62 | Poorer mental quality of life | t = 3.74** | High |

| Reduction in FCR post-treatment | Full results missing** | ||||||

| Hart et al. 9, USA | Longitudinal (18-month follow-up) | 333, prostate | Not stated | Fear of Cancer Recurrence Scale 62 | Less treatment satisfaction | r = −0.32** | High |

| Poorer mental quality of life | r = −0.43** | ||||||

| Poorer physical quality of life | r = −0.30** | ||||||

| Llewellyn et al. 7, UK | Prospective | 82, head/neck | Newly diagnosed | Single item | Perceptions of severe consequences | r = 0.39** | High |

| Stronger emotional representations | r = 0.38** | ||||||

| Denial coping | r = 0.29* | ||||||

| Positive reframing coping | r = 0.33* | ||||||

| Use of religion coping | r = 0.29* | ||||||

| Planning coping | r = 0.41** | ||||||

| Lower optimism | r = −0.40** | ||||||

| Greater anxiety | r = 0.50** | ||||||

| van den Beuken-van Everdingen et al. 12, Netherlands | Prospective | 136, breast | Not stated | Concerns about Recurrence Scale 6 | Pain | β = 0.28** | High |

| Younger age | β = −0.2*1 | ||||||

| Poorer quality of life | |||||||

| Physical functioning | r = −0.22** | ||||||

| Social functioning | r = −0.39** | ||||||

| Role limitations | r = −0.24** | ||||||

| Mental health | r = −0.57** | ||||||

| Vitality | r = −0.38** | ||||||

| General health | r = −0.27** | ||||||

| Bergman et al. 33, USA | Prospective | 476, prostate | Not stated | Memorial Anxiety Scale 64 | Unpartnered patients | Parameter estimate 5.79* | High |

| Hodges and Humphris 20, UK | Prospective | 101, head/neck | Newly diagnosed | Worry of Cancer Scale 59 | Distress | β = 0.22** | High |

| Mehnert et al. 15, Germany | Cross-sectional | 1083, breast | 3.9 years | Fear of Progression Questionnaire 65 | Married/divorced | η = 0.02** | High |

| Unemployed | η = 0.03** | ||||||

| Younger age | r = −0.17** | ||||||

| Children | d = 0.14* | ||||||

| Disease progression/ recurrence | |||||||

| Chemotherapy | η = 0.01** | ||||||

| Perceived impairments | η = 0.02** | ||||||

| Depressive coping | η = 0.10** | ||||||

| Active problem-oriented coping | |||||||

| Intrusion coping | β = 1.80** | ||||||

| Avoidance coping | β = 0.55** | ||||||

| Hyperarousal coping | β = 0.62** | ||||||

| β =0.69** | |||||||

| β = 0.45** | |||||||

| Simard and Savard 56, Canada | Cross-sectional | 227, breast | 4.9 years | Concerns about Recurrence Scale 6 | Women | r = 0.31** | High |

| 246, prostate | 4.9 years | Fear of Recurrence Questionnaire 18 | Younger age | r = −0.31** | |||

| 49, lung | 3.8 years | Chemotherapy | r = 0.26** | ||||

| 78, colorectal | 4.2 years | Radiotherapy | r = 0.12** | ||||

| Surgery | r = 0.10** | ||||||

| Cancer progression | r = 0.14** | ||||||

| Skaali et al. 29, Norway | Cross-sectional | 1336, testicular | 11.4 years | Single item | Younger age | OR 1.51** | High |

| Neuroticism | OR 1.24** | ||||||

| Intrusion | OR 1.18** | ||||||

| Avoidance | OR 1.04** | ||||||

| McGinty et al. 27, USA | Cross-sectional | 155, breast | 6–24 months post-treatment | Modified Cancer Worry Scale 35 | Younger age | β = −0.16* | High |

| Stage of disease | β = 0.14* | ||||||

| High threat appraisal | β = 0.61** | ||||||

| Perceived vulnerability | β = 0.58** | ||||||

| Rogers et al. 35, UK | Cross-sectional | 123, head and neck (cohort 1) | Not stated | Fear of Recurrence Questionnaire 18 | Low mood about cancer | 69%* | Mod |

| 68, head and neck (cohort 2) | Anxious about cancer | 67%** | |||||

| Poorer quality of life | 35%* | ||||||

| Rosmolen et al. 46, Netherlands | Cross-sectional | 95, Barrett's neoplasia | Not stated | Worry of Cancer Scale 59 | Oesophagus-preserving treatment | Mean difference = 10** | High |

| Shim et al. 37, South Korea | Case–control | 112, breast, gastrointestinal, lung, other | 14.5 months | Fear of Progression Questionnaire 4 | Recurrence | F = 5.76** | High |

| Dissatisfaction with treatment | r = −0.26** | ||||||

| Simard et al. 5, Canada | Cross-sectional | 977, breast | 3.3– 4.3 years | Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory 1 | Intrusive thoughts | OR = 28.6* | High |

| 92, lung | No prostate cancer | Full results missing* | |||||

| 727, prostate | |||||||

| 188, colorectal | |||||||

| Janz et al. 26, USA | Cross-sectional | 1837, breast | Not stated | Worry of Cancer Scale 59 | Ethnicity | β = 0.86** | High |

| Younger age | β = −0.34** | ||||||

| Employed | β = 0.12* | ||||||

| Pain | β = 0.48** | ||||||

| Fatigue | β = 0.39** | ||||||

| Radiotherapy | β = 0.29** | ||||||

- NA, no association; BCT, breast-conserving treatment; POMS, Profile of Mood States; RCT, randomised controlled trial; FCR, fear of cancer recurrence; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

- * p < 0.05;

- ** p < 0.01.

Overall assessment

The information gathered was synthesised into four evidence levels: (i) strong evidence: consistent findings of an association in the same direction in at least three studies; (ii) moderate evidence: at least two studies reported a significant association in the same direction with one or none in the opposing direction; (iii) inconsistent evidence: inconsistent findings whereby no clear directionality in the findings was apparent ; (iv) weak evidence: only one study available with supporting evidence or studies consistently identified no association.

Results

The search strategy resulted in 420 bibliographic records, reduced to 257 articles following the exclusion of duplicates and to 36 following application of the inclusion criteria. Backwards organic searching identified a further seven articles. The forwards (citation) search did not identify further relevant articles. Forty-three studies were included in the review. The majority of studies were classified as high quality (Table 1), 11 as moderate quality and none as poor quality. Twenty-two studies focussed on breast cancer, five on prostate and testicular cancers, five on head and neck cancer, one on gynaecological cancers, one on haematological cancer, one on colorectal cancer, one on renal cell carcinoma and one on early Barrett's neoplasia. In addition, six studies covered mixed cancer types.

Eleven studies utilised a longitudinal design with follow-up periods ranging from 12 weeks to 18 months and between two and four data collection points. Retention rates between initial and final data collection ranged from 73% to 90%. Eight studies reported that FCR changed minimally over the periods examined 9, 14, 16, 24, 55, 31, 57. However, three studies reported that FCR decreased between the first two time points measured 21, 36, 47.

Demographic factors

Younger age was consistently associated (in 14 studies) with greater FCR. Older patients reported less fear in breast 6, 12, 14-16, 22-27, 47, endometrial 24, orofacial 17, gynaecological 28, testicular 29 and mixed cancer types 56. In contrast, two studies did not find a significant association between age and FCR 7, 18. However, age remains an important predictor of recurrence worry in multivariate models 14.

Contradictory findings were reported for gender, ethnicity and educational status. Llewellyn and colleagues 7 did not identify any noteworthy relationship between gender and FCR. Simard and Savard 56 found that women reported greater FCR than men although this finding did not hold once cancer type was controlled for. In addition, only one study reported that medium educational level was associated with greater FCR 14.

No clear association between ethnicity and FCR emerged 7. Two studies reported that African-American survivors were less fearful than Caucasian survivors 26, 32. Moreover, Janz and colleagues 26 also identified higher levels of worry about recurrence among Latina women.

There was a mixed pattern of findings for marital status. Six studies reported that following multivariate analysis marital status was unrelated to FCR 5, 7, 12, 18, 26, 28. In comparison, Bergman and colleagues 33 found that men with partners reported less fear of recurrence, and a further study reported that being either married or divorced was associated with greater FCR 15.

Concurrent family stressors were predictive of elevated FCR 30. Family resources, including family hardiness and social support, were unrelated to FCR although women who had fewer significant others with whom they could discuss concerns reported greater FCR 18. Mehnert and colleagues 15 found that having children was significantly associated with FCR. In addition, having younger children (under 21) was associated with greater FCR 34.

Cancer and treatment-related factors

None of the studies included in the review found an association between time since diagnosis and severity of self-reported FCR 6, 15, 30, 56. There were some differences in reports of FCR across cancer types. Prostate cancer patients reported lower FCR than patients with breast, colorectal and lung cancer 5. However, greater FCR was observed among breast cancer survivors than among endometrial cancer survivors 24.

Five studies reported that cancer stage was not associated with FCR 6, 12, 18, 19, 26. In contrast, two studies 27, 36 reported that breast cancer patients with stage I diagnosis reported less FCR than patients with stage II. Moreover, patients with cancer recurrence or progression reported greater FCR in comparison with controls 37.

Mixed evidence emerged for an association between treatment type and FCR. Skaali and colleagues 29 reported that treatment type for prostate and testicular cancer was not a significant predictor. However, five studies reported that chemotherapy was related to greater FCR among breast cancer survivors 14, 15, 38, 39, although this was not upheld in multivariate analyses. In a further multivariate analysis with a breast cancer sample, radiation therapy was predictive of greater worry 26. Four studies found no relationship between treatment type and FCR 18, 28, 30, 35 among a range of cancer types. However, the relationship between treatment type and FCR was reported to be influenced by treatment satisfaction 9 and symptom control 26.

Mixed evidence emerged for an association between type of surgery and FCR. Eight studies reported no difference between mastectomy and breast-conserving therapy 6, 22, 23, 40-43. However, two studies 6, 25 reported that patients undergoing breast-conserving therapy reported greater FCR than mastectomy patients. Conversely, three studies reported greater FCR among mastectomy patients compared with those receiving breast-conserving therapy 14, 44, 45. The discrepancy may partly be explained by the differing methodologies used and by the single treatment centre focus of most studies, whereby there may have been different surgical approaches or information provision.

Patients who underwent compulsory nephron-sparing surgery for renal cell carcinoma were significantly more fearful of cancer recurrence than those who underwent radical nephrectomy or elective nephron-sparing surgery 38. In addition, one study reported that preserving the oesophagus using endoscopic therapy in early Barrett's neoplasia resulted in greater reported FCR 46.

Psychological factors and coping responses

Mixed evidence emerged for the association between psychological factors and FCR. One study identified the association between personality, in particular neuroticism, and FCR 29. Furthermore, an association was found between low mood or psychological distress (including anxiety and depression) and FCR 7, 16, 17, 20, 35, although the directionality of such a relationship was not apparent. Finally, two studies also identified an association between intrusive thoughts and FCR 5, 29.

Two studies 7, 32 reported that lower optimism was associated with greater FCR, and optimism was the strongest predictor of FCR following treatment (excluding baseline FCR) 7. The same study identified that illness perceptions, including perceptions of more severe consequences and stronger emotional representations, were associated with FCR. In addition, conceptualising cancer as a chronic illness was associated with greater FCR 36. Furthermore, greater perceived physical impairments 15 and appraising cancer as having less positive meaning 30 was associated with greater FCR. McGinty and colleagues 27 reported a correlation between risk perceptions of breast cancer (vulnerability and severity) and greater FCR.

Low self-esteem, denial coping and avoidance-orientated coping were predictors of future FCR 16, 29, 47. In addition, both depressive coping and active problem-oriented coping were associated with greater FCR 15.

Quality-of-life domains were associated with FCR in five of the studies. In four studies, there was an observed association between poorer physical and mental-health-related quality of life and FCR 9, 12, 19, 35. In one study, there was an association between mental-health-related quality of life only and FCR 21.

Factors triggering FCR

One study reported that hearing of another's diagnosis, exposure to media information or an annual check-up influenced reports of FCR 31. In addition, experiencing new or ongoing side effects or symptoms (especially pain) was associated with reports of greater FCR 12, 26, 29, 30, 32. Furthermore, Humphris and Rogers 47 identified a weak relationship between FCR and smoking behaviour.

Discussion

This review aimed to identify factors associated with FCR in cancer patients. Strong evidence emerged for a relationship between FCR and younger age, coping responses, poorer quality of life and cues (new symptoms, pain and follow-up appointments). Moderate evidence was found for beliefs (e.g. perceptions of vulnerability) and demographic factors (ethnicity, having younger children). Finally, inconclusive or weak evidence was found for cancer-related factors (cancer type, stage, treatment type), socio-demographic factors (gender, education, employment) and social resources (family resources/stressors, significant others). Findings from the majority of studies suggest that FCR remains fairly stable over time. However, most studies reporting on changes in FCR examined the concept post-treatment and over relatively short follow-up periods. Further longitudinal evidence would improve the assessment of the stability of the FCR profile over the survivorship trajectory. This review found evidence of an association between baseline FCR and later FCR, which would suggest that if FCR is initially high, it is likely to remain elevated. Actual cancer recurrence or progression was also associated with FCR 37; however, causality cannot be inferred from these studies given the cross-sectional designs utilised.

The factor most consistently associated with FCR was younger age. Younger survivors may perceive their cancer as more unexpected 6 and report higher levels of anxiety and depression in general 48, 49. Moreover, two studies reported that survivors with young children experienced greater FCR 15, 34. Parents may be concerned about a child's emotional and behavioural adaptation to a parental diagnosis of cancer 50, and both parent and child may have significant fears about how the child would cope without the parent 51. Survivors of cancer who have children may benefit from a family-orientated psychological intervention that accounts for the emotional concerns of both the survivor and their children 52.

The review found strong evidence for an association between physical symptoms and elevated FCR 30, as survivors may attribute unrelated symptoms to cancer recurrence. Experimental evidence suggests that somatic cues, such as the occurrence of symptoms, trigger beliefs about vulnerability and thereby elicit cancer worry 53. Research thus far suggests that socio-demographic and disease-related factors do not contribute significantly to FCR 7. Inconsistencies emerged regarding the role of education in FCR. Highly educated patients may have a greater understanding of the implications of a diagnosis of cancer, whereas a low level of education may impact on the information that is provided 26. Finally, ethnicity may be important, with a growing body of research suggesting that African-American women report lower levels of FCR than Caucasian women 27.

Inconsistencies existed with regard to type of breast cancer surgery. The scarring that follows mastectomy may remind patients of their cancer 22, 39, and evidence suggests that breast cancer survivors would benefit from improved information provision and management of expectations with regard to breast reconstruction 66, 67. Conversely, patients undergoing a lumpectomy may experience greater FCR than mastectomy patients as they fear the cancer has not been fully removed 54. Conservative treatments such as endoscopic therapy for oesophageal cancer 55 and nephron-sparing surgery for renal carcinoma 38 are associated with FCR, which may relate to beliefs about whether the cancer has been fully removed.

A range of psychological factors were found to be associated with FCR. There was some evidence for an association between FCR and other forms of psychological distress (i.e. depression) although the designs of the studies did not allow for consideration of the directionality of such relationships. In addition, there was evidence that FCR is associated with poorer mental-health-related quality of life. Further studies examining the development of FCR and its relationship to other aspects of psychological distress (i.e. depression) would contribute to the understanding of the trajectory of FCR and inform the development of interventions targeting FCR and other components of psychological distress. Such interventions to date have focussed on reducing fear of recurrence, targeting illness perceptions and inappropriate checking behaviour using a form of cognitive behavioural therapy 68 or reducing psychological distress in general among survivors using a group intervention 69.

Family factors (including family stressors and social support) 30 and gender appeared unrelated to FCR although this may reflect that few studies have examined these factors to date. The majority of studies were conducted with female cancer patients (gynaecological and breast cancers); therefore, the role of gender requires further exploration employing larger samples of mixed-gender cancer types.

The primary studies presented in this review had a range of limitations that need to be considered. The majority of the studies recruited homogenous samples in that participants were mostly White, well-educated and married. In addition, a number of the studies acknowledged the small samples sizes recruited and in some cases the low initial response rates for recruitment into the studies. Although reported response rates varied, the majority of studies reported little about non-responders. Given that more distressed individuals would be less likely to respond, then the prevalence of FCR may be underestimated in these studies. Additionally, FCR was assessed using a variety of measures, making it difficult to compare across studies. Some measures relied on a single item, which could be considered less reliable and more likely to increase the error variance in the sample. Furthermore, the measures used were not appropriate to determine if the observed levels of FCR were of clinical significance. The acquisition of such information would be useful to inform the development of interventions aimed at reducing FCR.

The designs of the studies reported in this review varied. Cross-sectional studies do not allow for changes in FCR over time to be observed and may be prone to recall bias on some of the measures used. Eleven studies utilised longitudinal designs, and although the attrition rates across time points were generally low, these designs incorporated relatively short follow-up periods. This would limit the assessment of the stability of the FCR profile over the survivorship trajectory. Furthermore, the designs utilised did not allow for the assessment of pre-treatment levels of distress or the identification of factors associated with the development of FCR. Such information would help the targeting and timing of interventions to reduce FCR among cancer survivors.

The review demonstrates that FCR is a common response to a cancer diagnosis and the associated treatments. The current literature in this field does not allow one to determine the factors contributing to the development of FCR or to determine the stability of FCR over the survivorship trajectory. Further research is necessary to identify the key predictors of FCR among cancer survivors to identify at-risk groups and key factors to be targeted in an intervention. This review highlights the importance of managing the physical and emotional consequences of cancer; however, further research is necessary to target interventions and to determine the timing of such interventions to reduce FCR among cancer survivors and support patients at risk of FCR 31. This review provides a first step towards meeting this aim.