A systematic review of the associations between empathy measures and patient outcomes in cancer care

Abstract

Objective

Despite a call for empathy in medical settings, little is known about the effects of the empathy of health care professionals on patient outcomes. This review investigates the links between physicians' or nurses' empathy and patient outcomes in oncology.

Method

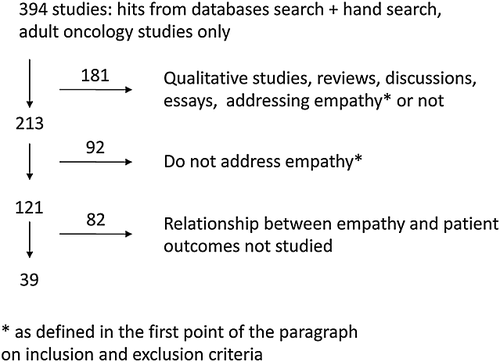

With the use of multiple databases, a systematic search was performed using a combination of terms and subject headings of empathy or perspective taking or clinician–patient communication, oncology or end-of-life setting and physicians or nurses. Among the 394 hits returned, 39 studies met the inclusion criteria of a quantitative measure of empathy or empathy-related constructs linked to patient outcomes.

Results

Empathy was mainly evaluated using patient self-reports and verbal interaction coding. Investigated outcomes were mainly proximal patient satisfaction and psychological adjustment. Clinicians' empathy was related to higher patient satisfaction and lower distress in retrospective studies and when the measure was patient-reported. Coding systems yielded divergent conclusions. Empathy was not related to patient empowerment (e.g. medical knowledge, coping).

Conclusion

Overall, clinicians' empathy has beneficial effects according to patient perceptions. However, in order to disentangle components of the benefits of empathy and provide professionals with concrete advice, future research should apply different empathy assessment approaches simultaneously, including a perspective-taking task on patients' expectations and needs at precise moments. Indeed, clinicians' understanding of patients' perspectives is the core component of medical empathy, but it is often assessed only from the patient's point of view. Clinicians' evaluations of patients' perspectives should be studied and compared with patients' reports so that problematic gaps between the two perspectives can be addressed. Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Introduction

Along with the psychological and physical upset caused by cancer, oncology patients are often overwhelmed by fears related to the uncertainty surrounding the illness and the courses of treatment while they deal with complex medical information 1, 2. For this reason, there is a large consensus that clinical empathy is of critical importance in oncology at all stages of the illness 3-9. However, two somewhat surprising facts were highlighted by recent critical reviews on empathy in medicine 10, 11.

The first is that the majority of studies dealing with empathy do not clearly define it 10. This is problematic because empathy is covered by a wide range of definitions and measures. In medical settings, empathy can be defined as ‘a predominantly cognitive (rather than emotional) attribute that involves an understanding (rather than feeling) of experiences, concerns and perspectives of the patient, combined with a capacity to communicate this understanding’ 12. Therefore, medical empathy implies both an ability to take perspective and the communication skills to convey this understanding in a warm and compassionate manner. Furthermore, empathy can be evaluated by the patient, the health care professional or by an external coder. It is thus necessary to define what is being studied in empathy research (i.e. the understanding of the other or the communication skill) and who assesses empathy.

The second surprising fact is that, because it is assumed that medical empathy is important and necessary, few scientific studies have explored the link between medical empathy and patient outcomes 11, 13. In fact, it is not known whether empathy is truly beneficial for patient outcomes in oncology. We define patient outcomes as observable or self-reported consequences of a medical encounter or relationship. Outcomes are often categorized by temporal criterion 14: within the consultation (e.g. patient's participation), proximal (e.g. immediate satisfaction with the consultation), intermediate (e.g. adherence to treatment) or distal outcomes (e.g. quality of life).

It would be helpful to provide health care professionals with accurate concrete advice rather than a non-evidence-based overall recommendation to be empathic in general. Indeed, in emotionally laden clinical contexts such as cancer, research suggests that being empathic has a psychological cost for health care professionals 15, 16 that can lead to ‘compassion fatigue’ 17. Moreover, reduced empathy may sometimes be necessary for physicians to fulfil their duties more adequately 18, 19. This could explain the lack of physician and nurse empathy sometimes reported in oncology 20-24 or why psychosocial issues are too rarely discussed by oncologists 25, 26. This also could be the reason why communication training programmes sometimes fail to improve empathy 27-29 and patient outcomes 30 in oncology.

This review aims to evaluate the current knowledge about patient outcomes associated with physicians' or nurses' empathy in adult oncology. The objectives are to: (i) give an overview of measures related to empathy in cancer research as well as investigated patients outcomes; (ii) study the associations between empathy and outcomes; and (iii) clarify the conditions in which these associations are enhanced. To our knowledge, this is the first review of this matter in oncology.

Method

Search strategy

The following databases were used: Medline, PsychINFO, Academic Search Premier and CINAHL. Limiters for adult population, English or French languages and oncologic population (when available) were used. Search terms were written so that ‘cancer or oncolog* or end-of-life or terminal* or palliat*’ had to appear along with ‘doctor* or physician* or nurse*’and along with ‘empath*’. All terms but empath* were specified as being only in the abstract and for studies from January 1990 to October 2011. The same research was also performed with ‘empathy’ or ‘perspective taking or role taking’ as subject headings. Furthermore, the available subject headings used for ‘physician/nurse relationships’ along with available subject headings for ‘patient outcomes’ were also used. In addition, all measures reported by Pedersen (2009) in his comprehensive review on empathy in a medical setting 10 were considered, and a new search was performed for each measure with the name of the measure instead of ‘empath*’ along with other unchanged criteria. The reference list of each retained study and relevant reviews or articles were also hand searched. A total of 394 studies were identified in this way.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

- They included a measure of empathy or of a component of empathy according to the definition of Hojat 12 (given earlier) and the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) questionnaire 31. The CARE was developed to measure empathy in medical settings and contains 10 patient-reported items on the clinician's ability to be warm and friendly, really listen to the patient, explain things clearly, be interested in him/her as a whole person and consider the patient's point of view for medical options. Studies encompassing one of these components (e.g. listening to the patient) were included.

- They dealt with adult cancer patients, in either curative or palliative settings.

- They assess the association between physicians' or nurses' empathy and one or more patient outcomes.

Articles were selected independently by two authors. Disagreements occurred for two articles on shared decision-making 51, 67. Following a discussion, it was decided that they should be included because shared decision-making implies the physician's ability to explain things clearly, listen to and consider the patients' point of view. Thirty-nine studies met these inclusion criteria (see Figure 1).

Results

Overview of the studies

Table 1 summarizes the 39 studies retrieved by outcome types and approaches of empathy assessment. Most of the outcomes are proximal and related to patients' satisfaction with clinicians or medical encounters or to psychological adjustment. In intermediate and distal outcome studies, only five 59-61, 64, 71 were prospective. In most samples, patients were assessed at the beginning of treatment or during treatment, but six studies included patients with advanced cancer or in palliative treatment 39, 45, 46, 48, 54, 55. Professionals were nurses in nine studies and physicians in the other 30 studies. One study 58 evaluated empathy with a clinician-reported questionnaire, and a perspective-taking task was used in two studies 49, 50. In other studies, empathy was evaluated using a patient-reported measure or the coding of clinicians utterances. None of the 39 reviewed studies evaluated empathy by using two different approaches (e.g. patient-reported measure and coding system).

| Authors | Samples | Empathy assessment | Patient Outcomes | Summary of results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients/clinicians (details reported when provided; when nothing mentioned clinicians are physicians) | Measure Design (not mentioned if cross-sectional) | Empathy measure associated: | ||

| In-consultation | ||||

| Communication coding | ||||

| Ishikawa et al. 32 | 129/12 follow-up encounter | RIAS ‘Emotional responsiveness’ cluster (i.e. categories of ‘shows concern’, ‘reassurance’, ‘self-disclosure’, ‘empathy’) | Active participation (e.g. ask questions, express emotion) | No association |

| Street et al. 33 | 65/16 lung cancer initial consultation | Street et al. coding system [34]: ‘Doctor supportive talk’ cluster (i.e. ‘reassurance’, ‘support’, ‘empathy’, ‘displays of interpersonal sensitivity’) | Active participation | With more participation (β=2.03, p<0.001) |

| Oguchi et al. 35 | 51/13 nurses chemotherapy education | The VERONA-CoDES-P Proportion of responses to patient cues/concerns that encourage emotional expression | Expressed cues/concerns | With a decrease in the number of patient cues/concerns, t(36) = −2.04, p = 0.049, β = −0.258 |

| Razavi et al. 36 | 115 nurses: randomized in a training workshop aimed at improving empathy or in a control group | Tally of emotional words related to distress | Use of emotional words related to distress | With more emotional words (p = 0.005) and greater difference (p = 0.003) in interviews with trained nurses compared to non-trained nurses |

| Maguire et al. 37 | Simulated patients/49 doctors and 134 nurses | Empathic statements of CRCWEM | Disclosure of significant information and mention of feelings | With both of the outcomes (respectively r = 0.18, p<0.005, and r = 0.23, p<0.002) |

| Immediately after the encounter | ||||

| Communication coding | ||||

| Eide et al. 38 | 36/4 | RIAS ‘Psychosocial exchange’ cluster | Satisfaction | Negatively with the outcome when psychosocial exchange occurs in the physical examination phase of the consultation ( ρ = −0.42, p = 0.01), but positively when during the counselling phase (ρ = 0.33, p = 0.05) |

| Uitterhoeve et al. 39 | 100 (45 with palliative treatment)/34 nurses | MIARSA cue-responding score is computed = [(‘exploration’+ ‘acknowledging’) -‘distancing’]/ (‘exploration’+ ‘acknowledging’+ ‘distancing’) | Anxiety and depressionSatisfaction | Only with satisfaction (β=0.09, p<0.05) |

| Shilling et al. 40 | 1816/160 oncologists randomized to attend communication skills training or not | MIPS ‘Expression of empathy’ category | Satisfaction | No association although oncologists’ empathy was significantly higher in the trained group (p = 0.003) |

| Ishikawa et al. 41 | 140/12 | RIAS ‘Emotional responsiveness’ cluster | Satisfaction | Negatively with satisfaction, β = −0.22, p <0.05 |

| Butow et al. 42 | 298/9 | Responses to emotional cues with Carkuff and Pierce system 43 | Satisfaction Anxiety immediately after and two weeks later | No association |

| Siminoff et al. 44 | 50/15 breast cancer | RIAS % of utterances coded as affective | Comprehension of, satisfaction, and regret with adjuvant therapy | Only and positively with no regret (univariate analysis, p <0.05) |

| Jansen et al. 45 | 105, 59% with palliative treatment/nurses | MIARS Four ways of responses to emotional cues: ‘exploration’, ‘acknowledging’, ‘distancing’, and ‘minimal encouragement’ (e.g. hmm) | Recall of information given during the consultation | Positively with the outcome for ‘minimal encouragement’ β = 1.05, p=0.06 Negatively for ‘distancing’, β = −0.81 p=0.02 No association for ‘exploration’ and ‘acknowledgement’ |

| Patient-reported | ||||

| Zachariae et al. 46 | 454, 38% with palliative treatment/31 | Empathy factor of the PPRI For example: ‘The physician may have understood my words but not my feelings’ | Satisfaction Patient changes in self-efficacy, distress, perceived control over the disease | Only with reduced distress in multivariate analyses (β=−0.24, R² change=0.06, p (F change) <0.01). |

| Takayama et al. 47 | 138/39 | Patient-centred communication subscale of an ad hoc questionnaire. For example: ‘your doctor seemed interested in what you had to say’ | Satisfaction Anxiety | With more satisfaction (r = 0.62, p <0.001)With less anxiety in multivariate analyses (F = 5.70, p = 0.02). With less anxiety for bad examination results but not for good results (significant interaction, t105 = 2.224, p = 0.02) |

| Rutter et al. 48 | 73 early stage and advanced cancer | Prospective Affective subscale of the MISS | Satisfaction immediately Coping and quality of life 6 weeks later | Only with satisfaction, but in early stage patient only (r = .73, p <.001). |

| Perspective taking task, ability to identify: | ||||

| Fröjd & von Essen 49 | 73/11 initial consultation | Much worry/information a certain patient experienced/wished | Satisfaction Hope to live a good life in spite of the disease | No association |

| Mårtensson et al. 50 | 82/nurses admission interview | Patient anxiety, depression, coping, and spiritual well-being | Satisfaction | Only underestimation (but not overestimation) of depressive symptoms associated with less satisfaction ( χ² = 7.02, p = 0.03) |

| Within one month after the encounter | ||||

| Gattellari et al. 51 | 233/physicians discussing treatment options | Patient role match in decision taking (i.e. achievement of the desired degree of participation) and perception of shared decision-making (ad hoc questions) | Anxiety Recall of information Satisfaction | Role match not associated with any outcomes Shared decision-making only with more satisfaction irrespective of the desired degree of participation (p = 0.0005) |

| Simmons & Lindsay 52 | 74/2 | Patient reported. Empathic understanding factor of the BLRI For example: ‘He wants to understand how I see things’ | Uptake and completion of post-surgical treatment | No association |

| Butow et al. 53 | 142 patients | Communication coding. CN-LOGIT 53 consultation style (i.e. authoritarian vs patient-centred) and doctor effect (hostile vs friendly) | Psychological adjustment Satisfaction Recall of information 1 to 3 weeks after the consultation | No association |

| Related to the overall relationship with the clinician, not in reference to a single encounter | ||||

| Patient reported | ||||

| Mack et al. 54 | 217 advanced cancer patients | THC scale For example: ‘to what extent does your doctor pay close attention to what you are saying’ | Burden of illness, emotional acceptance of terminal illness, psychological symptoms, functional status | With less burden (r = −0.19, p = 0.006), more emotional acceptance of illness (r = 0.31, p<0.001), less psychological symptoms (r = −0.18, p < 0.007), better functional status (r = 0.22, p = 0.001), more emotion-based coping (r = 0.28, p<0.0001), but less avoidant coping (r = −0.15, p = 0.02) |

| Spencer et al. 55 | 635 advanced cancer patients | Three questions: ‘Do you think doctors here see you as a whole person?’, ‘Treat you with respect’, ‘Do you understand most of what your doctor explains to you?’ | Anxiety disorders (yes or no) | ‘See you as a whole person’ and ‘explanations’ items associated with no anxiety disorders (respectively OR = 0.24, p = 0.0003, and OR = 0.35, p = 0.0351; multivariate analyses) |

| Galbraith 56 | 66/nurses | Ad hoc questions on nurses emotional support | Satisfaction | With more satisfaction ( r = 0.70, p<0.01) |

| Tustin et al. 57 | 92 patients and 80 survivors | Empathy subscale of the PMH-PSQ-MD For example: ‘It seems to me that the doctor was not interested in my emotional well-being’ | Choice of the most preferred source of cancer-related information | Negatively with Internet as the most preferred source (r = −0.23, p=0.002)Positively with the oncologist as the most preferred source (r = 0.21, p=0.004) |

| Nurse reported | ||||

| Reid-Ponte 58 | 65/65 nurses | ‘Perceiving, feeling, and listening’ empathic mode of the LEP. For example: ‘Seems to understand another person's state of being’ | Distress | Positively (unexpected direction) with patient distress (p<0.05, univariate analysis) |

| Intermediate outcomes, > 1month and < 1 year after encounter | ||||

| Communication coding | ||||

| Smith et al. 59 | 89 breast cancer | M-PICS ‘Facilitates’ cluster (i.e. support and encouragement of patient question-asking)Prospective: 4 and 12 weeks after the encounter | Pain management, quality of life, distress, satisfaction | Only with more satisfaction at both times (β=0.42, p < 0.0001). |

| Ong et al. 60 | 96/11Initial consultation | RIAS ‘Verbal attentiveness’ cluster (e.g. ‘showing understanding’, ‘empathy’)Prospective: one week and 3 months after the consultation | Quality of lifeSatisfaction with: (1) The overall consultation (2) Physician's interpersonal communication | Only with physician interpersonal communication at T2 (r = −0.24; p<0.05, unexpected direction) |

| Smith et al. 61 | 55/20 Early breast cancer Treatment options consultation | RECC: four levels of empathy in response to each cue/concern. For example: level 0 is ignorance or rejection. Average level computed Prospective: 2 weeks and 4 months after the consultation | Anxiety, decisional conflict, satisfaction with the consultation and doctor shared decision-making skills | Only with two-weeks anxiety, β=0.431, p=0.011 (unexpected direction) |

| Patient reported | ||||

| Maly et al. 62 | 257/surgeons Diagnosis disclosure | Ad hoc items assessing surgeon's emotional support [63]: For example: ‘your surgeon was extremely compassionate ’Retrospective, 8 months from diagnosis | Perceived efficacy in the interaction with the physician, positive coping style, breast cancer knowledge, quality of life | No association |

| Schofield et al. 64 | 131/5 surgeons Melanoma Diagnosis disclosure | Ad hoc questions Prospective: 4 (T1), 8 (T2) months and 1 year (T3) after initial consultation | Satisfaction (T1), Anxiety and depression (T2,T3) | Giving as much information as desired and attending to the patient's emotional reactions associated with higher satisfaction and less anxiety Encouraging the patient to be involved in treatment decisions associated with less depression (multivariate analyses, all p < 0.0005). |

| Ptacek & Ptacek 65 | 120/50 Bad news consultation | One single ad hoc item: ‘The doctor tried to empathize with what I was feeling ‘Retrospective: 6 months from diagnosis | Satisfaction | Positively with satisfaction controlling for other patient-centredness items, Wald test = 6.38, Odds ratio = 5.84, 95% CI: 1.48−22.97, p<.05 |

| Roberts et al. 66 | 100/surgeons Breast cancerDiagnosis disclosure | CDIS total score (caring, information, and hope given)Retrospective: 6 months after surgery | Psychological distress | With less distress (β = −0.23, p <0.05) |

| Mandelblatt et al. 67 | 718/138 surgeonsBreast cancer | Shared decision-making items adapted from Lerman et al. 68. For example: ‘My surgeon asked me about my worries about breast cancer ‘Retrospective: 4 months after surgery | Satisfaction with surgery and treatment Subjective impact of cancer | With greater satisfaction in multivariate analyses (p =0.003) With (unexpected direction) a greater perceived impact on life (OR = 1.10, 95%CI: 1.04−1.116) |

| Walker et al. 69 | 58/medical staffHead and neck, colorectal cancer | Two ad hoc questions related to whether patient emotional reactions have been sufficiently addressed the last 2 months Retrospective: 2 months after diagnosis | Overall satisfaction with clinic visits | With more satisfaction in univariate (p<0.003) but not in multivariate analyses |

| Distal outcomes | ||||

| Patient reported | ||||

| Mager & Andrykowski 70 | 60 breast cancer Diagnosis consultation | CDIS subscales of caring and mutual understanding.Retrospective, 28 months from diagnosis | Anxiety, depression, cancer-related post-traumatic stress symptomatology | Only caring subscale associated with less anxiety (β = −0.23, p <0.05), depression (β = −0.25, p <0.05) and post-traumatic stress (β = −0.29, p <0.01) |

| Omne-Pontén et al. 71 | 99 (T1) and 66 (T2) breast cancerDiagnosis consultation | ‘Negative experience at time of diagnosis’ (i.e. physician's lack of empathy, yes/no answers). Retrospective at 13 months Prospective: 6 years after diagnosis | Psychosocial adjustment | With the outcome at 13 months (P(χ²) = 0.07) but not at six years |

| Neumann et al. 72 | 326 patients | CARE questionnaire For example: ‘How was the doctor being interested in you as a whole person? Retrospective: 22 months from diagnosis | Desire for more information from physician Depression and quality of life | Negatively with desire for more medical information (from β= −0.33 to −0.68 according to the nature of info)Negatively with depression via less desire for info (indirect effect, β=−0.27)Positively with socio-emotional-cognitive quality of life via less desire for info (indirect effect, β=0.24) |

| Thind et al. 73 | 789 breast cancer/surgeons | Four questions exploring 1) the time spent by the surgeon, 2) his/her listening, 3) respect, 4) clarity of explanations Retrospective: 18 months from diagnosis | Satisfaction with surgical treatment | Only time spent (OR = 2.75, 95% IC [1.31−5.75] ) and clarity of explanations (OR = 3.08, 95IC [1.18−8.07]) associated with satisfaction in multivariate analyses |

| Neumann et al. 74 | 323 patients | CARE Retrospective, 2 months from diagnosis | Probability to have no unmet medical and psychosocial information needs | Associated with the outcome in multinomial logistic regression (p <0.001) |

- As far as possible, presented results come from multivariate analyses. When nothing is mentioned, ‘satisfaction’ outcome refers to the clinician/consultation.

- PMH-PSQ-MD, Princess Margaret Hospital Patient Satisfaction with Doctor Questionnaire 75; CARE, Consultation and Relational Empathy 76; PPRI, Physician–Patient Relationship Inventory 77; BLRI, Barrett-Lennard's Relationship Inventory 78; RIAS, Roter Interaction Analysis System 79; MIARS, Medical Interview Aural Rating Scale 80; LEP, La Monica Empathy Profile 81; RECC, Response to Emotional Cues and Concerns 42; CDIS, Cancer Diagnostic Interview Scale 66; VERONA-CoDES-P, Verona Coding Definitions of Emotional Sequences for health care Providers' responses 82; M-PICS, Modified-Perceived Involvement with Care Scale 83; MIPS, Medical Interaction Process System 84; THC scale, The Human Connection Scale 54; MISS, Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale 85; CRCWEM, Cancer Research Campaign Workshop Evaluation Manuel 86; OR, odds ratio.

Associations between empathy and patient outcomes

In-consultation outcomes

Oncologist empathic behaviour during consultation was related to active patient participation in one study focusing on an initial consultation 33 but not in another one on a follow-up encounter 32. Clinicians addressing patients' emotional issues seem to prompt patients to disclose information and emotions 36, 37, although the contrary result was observed in a chemotherapy education session 35.

Proximal and intermediate outcomes

Only three studies reported less patient satisfaction in relation to clinician's empathy 41, 50, 60. In the other 16 studies dealing with clinician's empathy and patient satisfaction, there was either no association 40, 42, 44, 46, 49, 53, 61, 69 or a positive link 39, 47, 48, 59, 64, 65, 67. One study revealed that patients appreciated empathy when it was provided in the counselling phase of the consultation but not when it occurred in the physical examination 38. Clinician's empathy was also associated with less distress in some studies 46, 47, 64, 66 but not in others 40, 43, 52, 60 and was even related to more negative psychological outcomes in two studies 61, 67. Clinicians' acknowledgement of patients' emotions and preferences regarding treatments does not seem to impact on patient recall of information or knowledge 44, 45, 51, 53, 62, whereas clinicians' lack of empathy clearly does 45. No association was observed with coping 48, 62, quality of life 48, 59, 60, 62, patients' hopes to live a good life in spite of the disease 49, pain management 59, adherence to treatment 52 or perceived control over the disease 46.

Distal outcomes

In distal outcome studies, patient-reported physicians' empathy was related to a lesser need for medical and psychosocial information 72, 74, less psychological distress 70, 72 and better psychosocial adjustment and quality of life 71, 72. The time taken by the surgeon and the clarity of explanations were related to greater satisfaction with treatment 73.

Outcomes related to the overall relationships with clinicians

In the five studies in this case 54-58, clinicians' empathy was related to better patients' outcomes in so far as empathy was a patient-reported measure: greater psychological well-being 54, greater satisfaction with care 56, no anxiety disorders 55 and the oncologist perceived by the patient as the most preferred source of information 57. However, when it was a nurse-reported measure, nurses' empathy was related to patient's distress 58.

Discussion

This review suggests that clinician's empathy is associated with higher patient satisfaction, better psychosocial adjustment, lesser psychological distress and need for information, particularly in studies with patient-reported measures and retrospective designs. On the contrary, results indicate that empathy is not related to patient empowerment (e.g. medical knowledge, coping). Divergent results were observed on certain outcomes such as quality of life.

As regards the divergent results, two points are worth discussing. Firstly, observed discrepancies may be better understood taking the disease trajectory or treatment phase into account. As patients' expectations are not the same in consultation 38, patient expectations and cognitive processing of the disease may also vary depending on disease trajectory or the consultation type (initial/follow-up) 97.

Secondly, measure-related issues may explain discrepancies. For example, measures such as the CARE 72, 74, ‘facilitating communication’ or ‘psychosocial exchange’ clusters 38, 59 might be considered as a ‘pro-active empathy’ whereby clinicians orient their consultation/care toward the patient with an interest in his/her concerns, preferences, etc. To some extent, this pro-active attitude could help anxiety in patients. On the other hand, measures such as the ‘emotional responsiveness’ cluster 32, 41, Medical Interview Aural Rating Scale 39, Medical Interaction Process System 40 or Response to Emotional Cues and Concerns 61 could be viewed as more ‘reactive empathy’ in response to pre-existing patient distress and explain negative associations between empathy and positive patient outcomes 41, 58, 60, 61. Furthermore, certain coding systems, such as the Roter Interaction Analysis System 32, 41, 44, 60, 90, compute the amount of empathic utterances made by clinicians, without considering how often they fail to give empathic utterances in response to patient's concerns or cues. In contrast, other systems such as the Medical Interview Aural Rating Scale 39, 45 or the Response to Emotional Cues and Concerns 42 compute a score that takes into account both the number of empathic responses and of non-appropriate responses. These measurements thus provide information about empathy and also about the lack of empathy which it seems crucial to investigate 45, 71.

Another insightful observation is that in the 20 studies where empathy is patient-reported, with the exception of three studies 52, 62, 67, empathy is always associated with at least one beneficial patient outcome. This suggests that the patient's point of view may be particularly informative compared with a coding system. It could be speculated that patient-reported measures take into account more cues of clinicians' empathy (e.g. genuine interest in the patient, non-verbal communication) than coding systems that often focus only on verbal utterances. The problem with the coding of utterances is that what is considered an empathic statement by one patient may be perceived as unempathic or neutral by another 91-94. This is why the ability to see things from the patient's perspective and thus meet his/her needs and expectations seems to be a key factor of empathy in medical settings 95, 96. In order to disentangle what is at stake in the beneficial power of empathy, future research should comprise several methods of empathy assessment (i.e. perspective taking, patient-reporting, coding systems) simultaneously.

Additional directions for future research can also be inferred from the four following limitations of this review. Firstly, of the 20 retrieved studies with patient-reported measures, specific empathy questionnaires were only used in six studies 46, 52, 57, 58, 72, 74 so that overall conclusions are difficult to extract. Secondly, few samples included patients in the palliative phase, whereas this phase is highly emotionally laden 87 which could confer higher expectations for empathy among patients in such contexts 3, 88. Thirdly, this review highlights the relative paucity of nursing-focused research in this field that is regrettable because their socio-emotional orientation is acknowledged in oncology 89. Fourthly, the cross-sectional designs of studies help to define the causal direction between empathy and outcomes. It may be that satisfied and mentally stable patients elicit more empathic attitudes in clinicians and not the contrary. Finally, qualitative studies could give information on how patients perceive the impact of clinicians' empathy on them regarding various outcomes (e.g. their well-being, hope, etc.) and on whether patients make a difference on that subject between nurses' and physicians' empathy.

In conclusion, in an oncological setting, clinicians' empathy is beneficially related to certain patients' outcomes such as patient's satisfaction and psychological well-being, although there is a lack of association in numerous studies. However, even in the latter case, it might be argued from an ethical point of view that medical empathy, as the will to do good and avoid harm, has an intrinsic value that requires no justification. Future research should clarify the conditions in which empathy is beneficial to formulate communication skills training and prevent compassion fatigue in clinicians.

Acknowledgements

The writing of this review was supported by INCA SHS 2008 and 2009, and a Sanofi-Aventis France grant given to Serge Sultan.