The wish to hasten death: a review of clinical studies

Abstract

It is common for patients who are faced with physical or psychological suffering, particularly those in the advanced stages of a disease, to have some kind of wish to hasten death (WTHD). This paper reviews and summarises the current state of knowledge about the WTHD among people with end-stage disease, doing so from a clinical perspective and on the basis of published clinical research. Studies were identified through a search strategy applied to the main scientific databases.

Clinical studies show that the WTHD has a multi-factor aetiology. The literature review suggests—perhaps in line with better management of physical pain—that psychological and spiritual aspects, including social factors, are the most important cause of such a wish. One of the difficulties facing clinical research is the lack of terminological and conceptual precision in defining the construct. Indeed, studies frequently blur the distinction between a generic wish to die, a WTDH (whether sporadic or persistent over time), the explicit expression of a wish to die, and a request for euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide.

A notable contribution to knowledge in this field has been made by scales designed to evaluate the WTHD, although the problems of conceptual definition may once again limit the conclusions, which can be drawn from the results. Studies using qualitative methodology have also provided new information that can help in understanding such wishes.

Further clinical research is needed to provide a complete understanding of this phenomenon and to foster the development of suitable care plans. Copyright © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Introduction

Western societies are once again debating the advisability of allowing assisted suicide or euthanasia. This debate usually arises from specific cases involving people with a severe disease prognosis and who regard death as the only way out of their situation. The controversy itself extends to those places where the law is currently in favour of some form of assisted suicide 1, 2, and the questions being posed include the following: Can physician-assisted suicide (PAS) and euthanasia be regarded as solutions, or at least as appropriate responses to certain situations? Would a law on assisted suicide and euthanasia benefit both the individual and society at large? At all events, it is worth noting that when engaging with this debate it is easy to lose sight of other questions that lie at the heart of the problem: How much do we actually know about the wish to hasten death (WTHD) in terminally ill people? Does it occur very often? What are the various motives that might lie behind such a complex phenomenon?

Recently, there has been a growing interest in analysing the WTHD in the clinical context 3, 4, especially in the area of palliative care 5-7, and this has been approached from different perspectives and disciplines 8, 9. Some studies have considered the attitudes of the general public and health professionals towards the wish of patients to hasten their death 10-12. Other research has explored various factors related with the WTHD 13-15, although some of these studies have limitations in terms of their design and the way in which data were obtained via indirect sources 16-18. In response to these limitations, other authors have explored the WTHD prospectively from the patient's perspective 16, 19, although the majority of them limit the WTHD phenomenon to a few study variables that are selected and assessed in a rather reductionist way. More recently, qualitative research has been conducted with the aim of understanding better the real meaning of the WTHD in all its aspects and in a naturalistic context 20-23. However, given the wide variety in both contexts and participants, the findings must be interpreted with caution.

This paper provides a review of published clinical studies in order to summarise current knowledge about the WTHD among people with end-stage disease.

Methods

The first step involved a detailed review of the international scientific literature regarding the WTHD and related concepts. Studies were identified primarily through conventional systematic searches of relevant electronic databases using medical subject heading terms and text words. The search strategy was conducted in MEDLINE (PubMed), PsycINFO, CINAHL, the Web of Science and CUIDEN. The timeframe covered for the databases used in the search was from their inception to January 2010. No restrictions were imposed. Table 1 lists the search strategy used.

| ♯1 | ‘Wish to hasten death’ [Text Word] |

| ♯2 | ‘Desire to hasten death’ [Text Word] |

| ♯3 | ‘Desire for death’ [Text Word] |

| ♯4 | ‘Desire for early death’ [Text Word] |

| ♯5 | ‘Euthanasia’ OR ‘physician assisted suicide’ [MeSH] |

| ♯6 | ♯1 OR ♯2 OR ♯3 OR ♯4 OR ♯5 |

| ♯7 | ‘Advanced cancer patients’ [Text Word] |

| ♯8 | ‘Advanced illness’ [Text Word] |

| ♯9 | ‘Chronic disease’ [MeSH] |

| ♯10 | ‘Chronic illness’ [MeSH] |

| ♯11 | ‘Terminal illness’ [Text Word] |

| ♯12 | ♯7 OR ♯8 OR ♯9 OR ♯10 OR ♯11 |

| ♯13 | ♯6 AND ♯12 |

| ♯14 | ♯13 NOT child* |

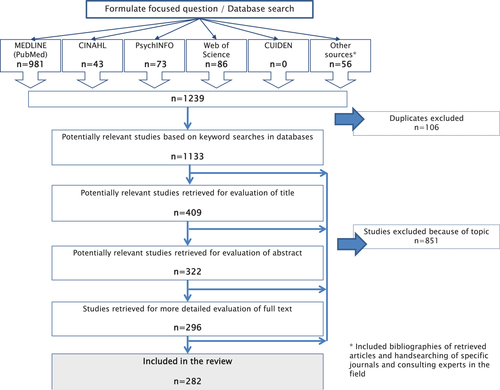

We did not restrict the search strategy to a particular type of research design. Figure 1 illustrates the search process followed.

Flowchart of search results

Of the 1239 references initially retrieved, 1133 potentially relevant citations were then identified. Analysis of their titles and abstracts reduced the pool to 226 articles of potential interest to this review. Reading these articles and reviewing their reference lists, as well as consulting with experts in the field, produced a final sample comprising 282 relevant studies.

The lead researcher (CM) carried out the literature search, which was then verified by another researcher (AB). First, CM was responsible for reviewing the 1133 citations, and the results of this search were then fed back to the other researchers. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the reviewers and reference to the full article. Finally, the research team reached an agreement on the final studies (n = 282) that should be included in the review, which was conducted using a narrative synthesis approach. The main findings that emerged from the review have been summarised under four headings: conceptualisation of the WTHD; aetiology of the WTHD; temporal stability of the WTHD; and epidemiology of the WTHD and instruments for measuring it.

Results

The studies were categorised by research design or focus topic (Table 2). In terms of the different types of articles identified, the analysis showed there to be similar proportions of clinical studies focussed directly on the WTHD, studies that analyse attitudes toward the WTHD, case report and case series and more theoretical or discussion papers. It should be noted that among the clinical studies that directly analysed the WTHD, only 14 obtained their data from patients themselves.

| Kind of study | Data sources | Number of studies | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical studies focussing directly on the WTHDa | 83 | 29 | |

| Quantitative (57 studies) | |||

| Health professionals | 20 | ||

| Palliative-care patients/patients in palliative care | 14 | ||

| Family members | 12 | ||

| Other patientsb | 6 | ||

| Retrospective study with official euthanasia and/or PAS data | 5 | ||

| Qualitative (26 studies) | |||

| Health professionals or family members | 15 | ||

| Patients in palliative care | 11 | ||

| Studies that analyse attitudes towards the WTHD | 75 | 26 | |

| Health professionals | 40 | ||

| Family members | 14 | ||

| Patients | 10 | ||

| General population | 8 | ||

| University students | 2 | ||

| Comments/Reflections: non-empirical studies | 73 | 25 | |

| Case report and/or case-series | 17 | 6 | |

| Health professionals' role with respect to the WTHD | 12 | 4 | |

| Clinical practice guidelines | 12 | 4 | |

| Reviews | 10 | 3 | |

- a aEvaluating clinical aspects of the WTHD: epidemiology, aetiology, etc.

- b bPatients in the early stage of the disease or with life expectancy of more than six months.

The breakdown of the MEDLINE (PubMed) search by publication date shows the growing interest in this topic over the last few decades (Table 3).

| Years | Number of articles |

|---|---|

| < 1970 | 1 |

| 1970–1979 | 35 |

| 1980–1989 | 144 |

| 1990–1999 | 373 |

| 2000–2009 | 428 |

- Performed in MEDLINE (PubMed) on 1/2/2010.

With regard to the geographical distribution of articles, around 50% of them (146) originated from the United States; they were distributed across almost all this country's states, although 25 referred to research conducted in Oregon. Europe was the next most common source of articles on this topic (n=80). More than half of these came from Belgium (n = 16) and the Netherlands (n = 26). The remaining studies were distributed among Spain (n = 9), the United Kingdom (n = 6) and other European countries (n = 12). Australia was another country that conducted a considerable number of studies (n = 21), followed by Canada (n = 17) and Japan (n = 10). Finally, four studies were conducted in Israel, two in China, one in India and one in Mexico.

The main sector of the population in which the WTHD has been explored comprises palliative care and cancer patients (Table 4).

| Main illness (when specified) | Number of studies |

|---|---|

| Cancer patientsa/hospice patients | 42 |

| AIDS | 18 |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | 7 |

| Chronic kidney failure | 4 |

| Elderly population | 3 |

| Chronic respiratory and cardiac failure | 1 |

- a aCancer patients in all stages of the illness and not necessarily in palliative care.

Discussion

Conceptualisation of the WTHD

Noteworthy among the first clinical studies of the WTHD were those conducted by Kraus 24, 25, who took an epidemiological perspective. This research was based on a number of surveys that gathered opinions about the WTHD among the general public and health professionals in Ontario. In these pioneering studies, the concept of the wish to die was used in a somewhat imprecise way, such that it could encapsulate both a generic or occasional desire and a more specific and persistent WTHD.

The growing interest in these topics led to numerous studies being conducted in the field, although their terminological, conceptual and methodological differences made it difficult to compare the results 4, 26, 27. For example, these studies did not distinguish clearly between a general wish to die, the WTHD and requests for euthanasia or PAS. Thus, one finds the indistinct use of terms such as ‘wish to die’ 28, ‘want to die’ 29 or ‘desire to die’ 30, 31, as well as ‘wish to hasten death’ 6, 22, ‘desire for early death’ 32 and other related expressions for requests for euthanasia or assisted suicide, such as ‘death-hastening request’ 33, ‘request to die’ 34, ‘request for euthanasia’ 35 and ‘request for physician-assisted suicide’ 36. Table 5 shows the number of studies identified that use each of these terms.

| Terms used | Studies |

|---|---|

| ‘Desire to die’ or ‘desire to hasten death’ or ‘desire for early death’ | 18 |

| ‘Wish to hasten death’ or ‘wish to die’ | 12 |

| ‘Consider hasten death’ or ‘consider hastening death’ | 9 |

| ‘Want to die’ | 5 |

However, in these concepts one could, at least in theory, differentiate between thoughts, wishes and intentions, which would imply progressively greater proximity to actual death. Thus, a distinction should be made between: (a) a generic wish to die; (b) a WTHD (sporadic or persistent over time); (c) the explicit manifestation of a WTHD and (d) the final stage in this process, i.e. the request for PAS or euthanasia. The concept of the WTHD would, therefore, appear around the midpoint of this process, it being more specific than a simple wish to die but coming prior to and being distinct from a request for euthanasia or PAS.

In response to these difficulties, a number of more recent clinical studies have sought to bring greater conceptual accuracy to the field 4, 30, 37, 38. Key authors such as Breitbart et al. 4 and Rosenfeld 39 have also recognised the need for this. However, these authors, who coined the term ‘desire for hastened death (DHD)’, use it as a ‘catch-all’ term covering everything from a generic wish to die to requests for euthanasia and PAS.

Faced with the lack of methods for quantifying patients' wish to die, and in an attempt to standardise the criteria used when studying the WTHD, Rosenfeld et al. 38 developed the Schedule of Attitudes Toward Hastened Death (SAHD) 40. This instrument contemplates a wide range of concepts, from general ideas about hastening death to requests for euthanasia and PAS. However, although the SAHD does distinguish between different notions, the fact that its final results are presented in numerical form means that, in practice, it does not really bring the conceptual accuracy it sets out to do. Nevertheless, the instrument has enabled researchers to compare this phenomenon in different populations and under different circumstances 4, 7, 13, 37, 41, 42.

The paper by Schroepfer 43 was the first clinical study to clearly highlight these conceptual differences. Using qualitative methodology, the author studied 96 patients (elderly people with fewer than six months to live) in order to examine the factors that motivated them to consider hastening their death. The findings led to the development of a conceptual framework that clearly distinguished between six stages or ‘mind frames’, which did not necessarily correlate with one another. The first referred to those elders who were neither ready for nor accepted death. The second concerned elders who were not ready for but did accept death. The third group comprised elders who were both ready and accepting. The fourth included elders who were ready, accepting and wishing that death would come. The fifth stage referred to elders who were considering a hastened death but who had no specific plan. And finally, the sixth mind frame was that of elders who already had a specific plan to hasten their death. According to Schroepfer 43, these six stages can be dichotomised according to whether or not there is a WTHD, and thus the last two stages would be grouped separately from the first four. Although there are no other studies that corroborate these findings, the paper is of considerable interest in that it offers a conceptual framework based on clinical data, which would seem to be essential from a theoretical point of view.

Aetiology of the WTHD

In recent years, there have been several published studies that have sought to identify, from a clinical perspective, the factors that might cause or foster the WTHD. Overall, these studies suggest a multi-factor basis for the WTHD 6, 44, one that includes pain, physical suffering, psychiatric disorders, and psychological or existential distress. In general, there is a broad consensus regarding the need for a greater understanding of the factors that might influence the WTHD, especially those which could potentially be modified through clinical or social interventions 14, 45.

Morita et al. 31 analysed the multi-factor nature of the WTHD by interviewing the families of patients who had died in a palliative care unit. They found that in 30% of patients who had wished to die the main reason for this was not the physical symptomatology but the existential suffering. Among the multiple causal factors behind this existential suffering the authors introduced the concept of a lack or loss of meaning to life.

In the most recent retrospective studies, the key factors behind the WTHD are reported to be of a psychosocial nature, especially the reduced ability to take part in pleasurable activities, the fear of pain or unmanageable symptoms as the disease progresses, the loss of autonomy, the feeling of being a burden, a perceived loss of dignity, the loss of meaning in life, a loss of control over bodily functions and over when and how one might die, and a loss of control in general 46-49. None of these studies analysed the presence of depression as a causal factor in the WTHD, and only two of them found evidence that pain motivated such a wish 46, 49.

However, depression is one of the most widely analysed factors among probable causes of the WTHD 50. The study by Breitbart et al. 4 found that patients who expressed a WTHD were around four times more likely to be depressed than were patients who did not wish to die or may not have considered it. Two studies conducted in Canada and the United States quantified the prevalence of depression in cancer patients who wished to hasten their death as being between 8.5 and 17% 4, 30.

Another factor that has been studied in relation to the WTHD is hopelessness, which is defined in this context as a cognitive state of pessimism 51. Hopelessness is reported in 44% of cases, as a state prior to depression 4. In the same line, a study conducted by Ganzini et al. 52 in Oregon reported that hopelessness is associated with a greater interest in PAS. In another study, the same authors 53 found that hopelessness was a predictive factor for the WTHD.

Pain, understood as physical suffering, has for many decades been regarded as one of the primary causes of the WTHD 54. However, since the end of the 1990s most studies have identified pain as an isolated factor that does not play a key role in fostering the WTHD 4, 31. As an alternative, some authors have introduced the concept of ‘overall physical distress’, which includes other physical signs and symptoms and whose presence is significantly associated with the emergence of a WTHD 36. Another factor that has been analysed as a potential cause of the WTHD is inadequate symptom control, behind which would lie not just pain but the whole range of physical symptomatology 3, 55, 56.

The feeling of being a burden to others is another causal aspect that has been studied recently 57. This feeling, which is closely related to dependence and a lack of autonomy, is defined as the patient's perception that his/her dependence on others has a detrimental effect on their personal or social development. Studies conducted in the United States and Japan found, respectively, that this feeling was present in 58% 57 and 98% 31 of patients who expressed a WTHD.

In summary, the main factors that have been related to the WTHD can be grouped into the following areas: (a) physical symptoms in the form of pain, physical suffering, distress, fatigue, dyspnoea, etc.; (b) psychological distress (hopelessness, the fear of pain, of advancing disease and physical deterioration, of a loss of autonomy, of aloneness) or psychiatric disorders (such as depression or related symptoms); (c) social factors, such as feeling like a burden to others, both physically and financially, and the perceived lack of social support; and finally (d) a wide range of factors that come under the label of ‘psycho-existential suffering’, such as the loss of autonomy, the loss of a social role, the wish to control how and when one dies, and the loss of meaning to life, the latter having received scant attention and conceptualisation in the literature.

Temporal stability of the WTHD

It should be clear from the above that patients with a chronic disease or those in the advanced stages of an acute illness often report some sort of WTHD, even when they are receiving palliative care 30, 31, 58. Although many factors have been identified as contributing to the WTHD, it has also been shown to be a fluctuating and unstable feeling in patients with advanced disease 17, 30.

Moreover, research has also found that the request to hasten death is not always accompanied by a genuine desire to die. In this context a systematic review by Alcázar-Olán et al. 59, the aim of which was to examine the medical and psychological criteria used to assess patients who requested a hastened death, concluded that the majority of such requests were, paradoxically, a request for help with living. One year later, a phenomenological study conducted by Coyle et al. 22 in a palliative care unit in New York reached similar conclusions. The authors noted the dual meaning of each expression of the WTHD, in the sense that it can reflect both a genuine desire to end one's life and a wish to live, it being a request for help in the face of a life that has become difficult, complicated, and painful 22.

Similarly, a qualitative study carried out in Belgium 7 found that some patients admitted to a palliative care unit and who had expressed a wish to hasten their death changed their minds after feeling that their plight had been heard. The authors of this study concluded that on many occasions the cause or the factor that triggers the initial decision is a feeling of social isolation or lack of support, which in this case was addressed through the nursing care given. Other researchers have argued the need to explore each individual request, as well as the possible reasons behind each expression of a WTHD 8, 60, 61. Emanuel 62 proposed a set of clinical guidelines for working with patients who express a wish to die, the aim being to ensure that each patient is correctly assessed and to rule out the presence of a potentially treatable cause.

Another phenomenological study conducted in Hong Kong 20 analysed the experience and expression of the WTHD in six palliative care patients. The authors concluded that behind each decision and request for euthanasia lay ‘hidden existential yearnings for connectedness, care, and respect’. Other similar studies 3, 63, 64 conducted in Canada and the United States have found that the WTHD becomes less strong when the patient perceives a degree of hope in the treatment and care being received.

Epidemiology of the WTHD and instruments for measuring it

Determining the epidemiology of the WTHD is not an easy task, due, above all, to the very nature of the phenomenon, its variability and dependency on external factors, and the problem of its conceptualisation. In addition, it is difficult to compare the results of clinical studies conducted using different methodologies.

A sizeable majority of the research published on this topic corresponds to retrospective studies which analyse data collected from indirect sources: health professionals or informal caregivers and relatives of patients who have expressed a WTHD 65, 66. With regard to prospective studies, they can be classified according to one of two methodological approaches. The first concerns those studies that analyse the responses of patients with a terminal illness to questions about potential future scenarios involving pain or unbearable suffering, discomfort, etc., where the patients must answer according to what they would do in such a situation 53, 67, 68. Clearly, however, these responses are based on preconceived attitudes and may not necessarily reflect a person's actual behaviour or decisions in real situations 69.

The second category of prospective research concerns those studies that use various questionnaires or scales that have been designed to quantify the WTHD. Studies of this kind first appeared during the 1990s. For example, Chochinov et al. 30 designed a study in which, in addition to socio-demographic variables and other possible factors related to the wish to die, they added a question about the wish to die soon. In the event that subjects responded affirmatively to this question they were then asked a further three questions in order to assess their degree of conviction. These questions constituted the first instrument developed to evaluate the wish to die, namely the Desire for Death Rating Scale (DDRS). The authors then used this scale with a sample of 200 palliative care patients and found a prevalence rate of 8.5% for a real and persistent wish to die.

O'Mahony et al. 70 used the same scale to analyse the desire for death in a sample of 64 cancer patients who presented both pain and depression. These patients were treated for their pain, and the authors took pre- and post-intervention measures. The former showed that a third of patients expressed a WTHD, whereas after pain relief only a quarter of the sample expressed such a wish, as measured by the DDRS. However, the researchers themselves suggest that the instrument may lack sensitivity in terms of detecting small changes in the quantification of the WTHD.

The DDRS has recently been modified by Kelly et al. 71 with the aim of producing an instrument that is capable of assessing both the intensity of the desire for death and potentially related factors. The modified version of the scale (the WTHD scale) comprises six items that are scored on a five-point Likert scale. In the study by Kelly et al. 71, the scale was administered to a sample of 256 terminally ill patients in Australia and showed adequate validity and reliability. Prevalence data showed that 14% of patients reported a strong WTHD 71.

Rosenfeld et al. 38, in an attempt to overcome the limitations of the scale developed by Chochinov et al. 30, designed the already-mentioned Schedule of Attitudes Towards Hastened Death (SAHD), which aims to evaluate the WTHD among terminally ill patients. The SAHD is a self-report scale comprising 20 true/false items, and it was initially validated in a sample of 195 AIDS patients. Analysis of its psychometric properties showed that the scale has adequate validity and reliability 37, 38. In this original patient sample, the mean number of items endorsed was 3.05 (SD = 3.80). The scale was subsequently validated in a sample of 92 terminally ill cancer patients 37, who endorsed an average of 4.76 items (SD = 4.3). Three categories can be distinguished according to the number of scale items endorsed: ⩽3, between 4 and 9, and >10, which correspond, respectively, to low, moderate, and high levels of desire to hasten death. However, this terminology may be somewhat schematic and the authors themselves acknowledge that scores below 10 could reflect states of mind in which people accept their own death 4, 39.

Since its publication the SAHD has been used by numerous authors to evaluate the WTHD. For example, Jones et al. 41 studied 224 cancer patients and found a strong WTHD among 2% of them. Ransom et al. 42 applied the same scale to 60 late-stage cancer patients being cared for at home and found high values for the WTHD in 3.3% of them. A recent study by Rodin et al. 7 analysed the WTHD in 326 ambulatory patients with either gastrointestinal cancer (all stages) or pre-terminal lung cancer, and reported high levels in 2% of patients. The study by Pessin et al. 13 analysed the WTHD in a sample of 109 patients in the advanced stage of AIDS, the mean score for the WTHD being 2.8 (SD = 3.0). Furthermore, 17% of this sample endorsed between four and seven scale items, while 10% endorsed more than seven. It should also be noted that the maximum score obtained was 15 (out of a possible 20). Finally, the study by Rabkin et al. 72 also used the SAHD, along with other instruments, to assess the presence of depressive symptoms and the WTHD in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), with high scores being obtained in 3.7% of patients.

One of the most widely cited prospective studies about the WTHD in non-cancer patients is that of Albert et al. 28. These authors assessed 80 patients with end-stage ALS who had been given fewer than six months to live. Patients were followed up prospectively and 53 died during the follow-up period. Of these, all of whom were assessed using the SAHD of Rosenfeld et al. 37, 10 had expressed the wish to die. In these 10 patients, scores on the SAHD showed a strong wish to die, the mean number of items endorsed being 12.6, compared to 4.8 in the group of patients who did not express a wish to hasten their death 28.

At all events, the existing literature still falls short of enabling investigators to be clear about when the WTHD reflects an underlying psychological disorder as opposed to some other situation within the conceptual framework, including the acceptance of death. Expressions of the wish to die, suicidal ideation, and requests for euthanasia or PAS have been identified in between 8 and 22% of cancer patients in palliative care units 4, 30, 73. In a sample of 378 HIV patients, Breitbart et al. 74 examined the relationship between an interest in PAS and variables such as pain and other physical or psychosocial symptomatology. They found that 55% of patients had considered PAS as a possible option at some point. Ganzini et al. 53 interviewed 100 patients with ALS in Oregon during the period 1995–1997, this being prior to the legalisation of PAS in this state. According to the authors, 56% of patients said they would consider PAS were it a legal option in the state 53. Another study by Ganzini et al. 52 concluded that 20% of patients admitted to hospices in Oregon had requested prescriptions for lethal medication, although on many occasions they did not use it. Emanuel et al. 17 studied attitudes towards euthanasia or PAS among 988 terminally ill patients, of whom 10.2% had seriously considered it with regard to their personal circumstances. A survey of 256 relatives of these patients found that 14 of them (1.4%) had submitted a formal request for euthanasia to their physician and 6 (0.6%) had stored medication, although they did not use it. Finally, one patient died following euthanasia and another made a failed suicide attempt. It should be noted that the incidence of depression in this sample was significant. Specifically, depressive symptoms were reported in 159 of them (16%), and 19.5% of these expressed an interest in both euthanasia and PAS. A multivariate analysis revealed that the patients who had expressed an interest in euthanasia and PAS were more likely to have symptoms of depression (OR = 5.29). This study also confirmed the temporal instability of the WTHD.

One of the most detailed studies about the possible causes of the wish to die is that conducted by Seale and Addington-Hall 29. These researchers analysed two surveys carried out in England, which focussed on the relative who cared for the patient during the last year of life. They found that 24% of those surveyed said that their deceased relative had, at some point, wished to die soon, while 3.6% said that the deceased relative had requested euthanasia 29.

The main limitation of the above-mentioned studies is that they fail to specify the type of wish expressed. In general, it is not known whether they refer to generic thoughts or desires or a genuine intention to hasten death. As such, determining the prevalence of the WTHD in chronically ill or end-stage patients continues to pose a serious challenge 75. Although numerous studies carried out mainly in the United States 49, 76-78, as well as in Holland 58, 79, have sought to specify the prevalence of the WTHD, the above-mentioned limitations (especially the lack of conceptual clarity) make it difficult to obtain comparable results 10.

Other known prevalence rates regarding the wish to die are those derived from the number of people who choose to end their life under the PAS law in Oregon or the euthanasia and PAS law in Holland. Between 1998 and 2001, a total of 140 people, almost all of them with end-stage cancer, requested PAS under the law in Oregon 80. Of these, 91 eventually died as a result of taking lethal medication prescribed under the law. Overall, the data show that 1% of patients at the end of their lives request PAS in Oregon, but only 0.1% of terminally ill patients actually die as a result of PAS 80, 81. In Holland, a study of patients with ALS found that 17% of a sample of 204 chose to die through euthanasia, while 3% opted for PAS 66.

This literature review shows that prevalence rates for the WTHD vary considerably from one study to another. These differences could be due both to conceptual aspects or sample characteristics as well as to the lack of a standardised measurement instrument. Taken together, the findings highlight the need not only for consensus and standardised criteria regarding the definition of the WTHD and related concepts but also for valid and reliable instruments to quantify it.

Final considerations

Although the WTHD is clearly of interest to clinicians and theorists, it poses considerable difficulties in terms of research. The WTHD is a complex phenomenon that raises questions about our current ability to care for and accompany patients through this most difficult of life stages. Moreover, in the context of serious or incurable illness, it affects a considerable number of patients, especially those facing the end of life. Medical advances, which have transformed diseases that once led to a quick death into chronic illnesses, coupled with increased life expectancy and other social phenomena linked to development, make it likely that far from being eradicated these situations will become more common.

Clinical studies show that the WTHD has a multi-factor aetiology. The growing body of literature over time suggests—perhaps in line with improvements in the treatment of physical pain—that overall suffering or the more general and spiritual aspects of the human being, including psychological and social aspects, are the most important factors underlying such a wish.

A better understanding of the WTHD, one which clarifies its conceptual limits and distinguishes between different stages or situations, is now necessary in order to further improve our knowledge and develop adequate interventions. Some strategies, such as the design of measurement instruments (for example, the SAHD of Rosenfeld et al. 38), may help to quantify the phenomenon and enable comparisons to be made. However, given the nature of the WTHD, research would be incomplete without the contribution of qualitative methodology. In this regard, the conceptual framework developed by Schroepfer 43 may be a good foundation on which to develop our understanding and devise care plans for each of the stages or ‘mind frames’ through which people can pass.

In sum, a multidisciplinary initiative is now required to improve the emotional and physical care that is offered to terminally ill people. An adequate approach to the WTHD, one that integrates both anthropological and clinical viewpoints, and which works closely with palliative care units, should thus be regarded as a priority goal.