Enterolith Small-Bowel Obstruction Caused by Crohn′s Disease

Abstract

We herein report on the successful surgical treatment of Crohn′s disease with enteroliths formed in the ileum. A 58-year-old man presented with abdominal colicky pain, and long-standing constipation. He was diagnosed as ileus due to enteroliths and was initially managed conservatively, but improvement was not observed either clinically or on radio imaging. We, therefore, performed a laparotomy, which revealed Crohn′s disease with enteroliths in the ileum. Because the enteroliths in the ileum were not mobile and could not be broken manually, we carried out a segmental bowel resection with the removal of the enteroliths. The pathology report revealed Crohn′s disease with enteroliths. Intestinal obstruction caused by enteroliths associated with Crohn′s disease occurs rarely, and is difficult to be diagnosed and managed.

1. Introduction

Crohn′s disease can present with many different symptoms. Bowel obstruction, bleeding, and diarrhea are all frequently encountered with Crohn′s disease. Enteroliths, on the other hand, are rarely seen in Crohn′s patients. The vast majority of these patients also had a long history of known Crohn′s disease [1]. In most cases, the enteroliths are relatively small and pass into the colon without causing any symptoms. We report an operative case of enterolith ileus with Crohn′s disease which was diagnosed at the time of surgery.

2. Case Report

A 58-year-old man presented with abdominal colicky pain, nausea, vomiting, and long-standing constipation. Physical examinations revealed a distended but soft abdomen with mild tenderness, especially in the right lower quadrant, audible peristaltic waves, and normal body temperature and blood pressure. He had a past medical history of a duodenal ulcer operation. An abdominal radiograph showed multiple air-fluid interfaces in the small intestine.

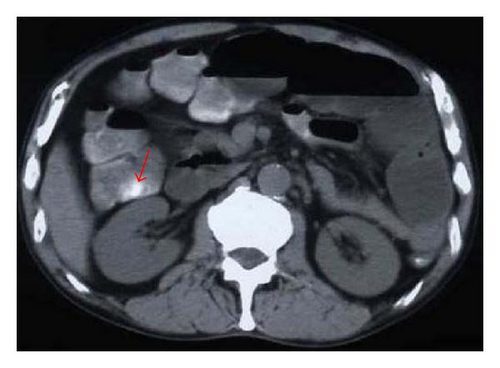

We initially treated the patient in a conservative manner with a nasogastric tube for upper intestinal decompression, a Foley tube in the urinary bladder to record urinary output, and a central venous catheter for intravenous fluid administration. Wide-spectrum antibiotics and prostaglandin were given. Laboratory studies showed a total protein of 4.9 g/dL. All other laboratory studies, including electrolytes and urinalysis, were within normal limits. Ultrasonography could not disclose the cause of the obstruction (figure not shown). Because improvement was not observed either clinically or with radio imaging over the next 7 days, the patient was treated with a long tube. A gastrograffin contrast X-ray, which was performed via the long tube, revealed minimal passage of gastrograffin beyond the middle portion of the ileum (see Figure 1). For the differential diagnosis of a possible tumor of the small intestine, computed tomography (CT) was performed, which showed a 25 mm hyperdense ellipsoidal focus in the thickened ileum (see Figure 2). These findings were strongly suggestive of intestinal obstruction due to enteroliths. Because there was no evidence of any form of improvement, elective surgery was scheduled 10 days after admission.

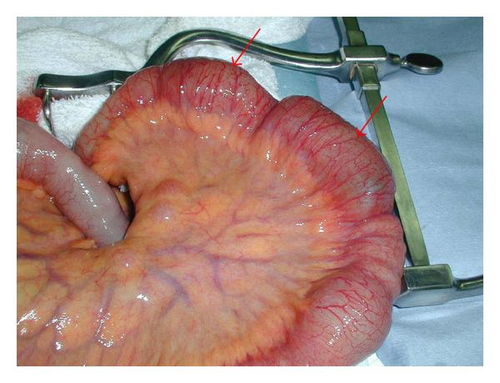

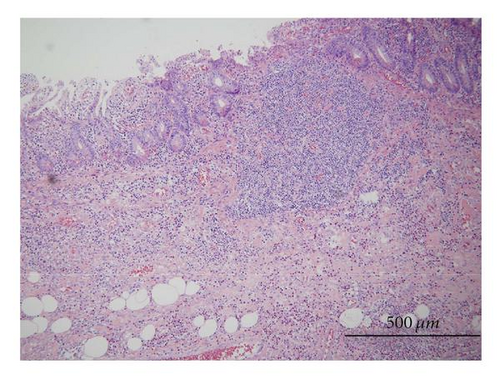

On laparotomy, there were no adhesions. There was severe narrowing in the ileum, and we could palpate two stone-like masses in the distal ileum with swelling of the lymph nodes (see Figure 3). Firstly, we attempted to crush the enteroliths manually without performing an enterotomy or segmental bowel resection, but they were too hard to be crushed. They could not be milked down to the colon, and malignancy could not be completely ruled out. Therefore, the ileal segment containing the enteroliths was resected, and bowel continuity was restored with an end-to-end anastomosis. The terminal 40 cm of ileum was involved with an inflammatory process, longitudinal ulcerations, and separate discrete small intestine strictures, all of which favored Crohn′s disease over other considerations of tuberculis enteritis or lymphoma (see Figure 4). The enteroliths measured 61 × 34 × 31 mm and 33 × 32 × 32 mm, respectively. Histological examination revealed marked ulcers with transmural inflammatory cell infiltration and lymphoid aggregates (see Figure 5). The patient′s postoperative course was uneventful, and he was discharged on the 25th postoperative day. At present, he is taking low residue and low fat foods in the daytime according to the instructions of his dietician, and in the nighttime, the elemental diet is infused through a self-intubated nasogastric tube using an infusion pump with an increased speed (100 mL/h).

3. Discussion

Enteroliths complicating Crohn′s disease are rare, with only a few cases documented in the literature [2–6]. In all of them, enteroliths occurred in areas of stasis proximal to a stricture, and the patients presented with signs and symptoms of intestinal obstruction. A common feature in all of these cases was a long duration of Crohn′s disease before development of enterolith. However, in our case, the patient was diagnosed as Crohn′s disease at the time of surgery.

Enterolithiasis in association with Crohn′s disease occurs secondary to stricture formation with obstruction, and in most instances is found within an area of saccular and aneursysmal dilation. This phenomenon is usually seen in the small bowel, although enterolith may occasionally develop proximal to colonic stricture with or without Crohn′s disease [4–6]. Enterolith formation in the small bowel is thought to be secondary to hypomotility or stasis [7]. Stasis then promotes bacterial overgrowth, decomposition of bile salts, and resulting precipitation and concretion. The lower pH of the duodenum and upper jejunum tends to keep calcium salts in solution and encourages bile salts precipitation [8]. Conversely, the alkaline milieu of the terminal small bowel is more favorable to the formation of mineralized stones. Hence, proximal small-bowel enteroliths are radiolucent and contain choleic or cholic acid. On the other hand, distal small-bowel enteroliths contain calcium, magnesium, or barium salts and are radiodense [4, 7]. As a result, enterolith ileus is detected incidentally at surgery or diagnosed by imaging studies such as radiography, CT, or endoscopy.

Primary enteroliths are divided into “false” and “true” enteroliths. False enteroliths are resulting from the agglutination of indigestible foreign materials such as seeds, bone, vegetable matter (phytobezoar), hair (trichobezoar), barium sulfate, and other man-made items [9]. Symptoms from enteroliths are usually those of intermittent obstruction, but there have been cases of acute complete bowel obstruction. Many patients were also found to have refractory chronic anemia [10]. Solitary or multiple enteroliths can be found either proximal to or within the strictured bowel segment. Single and multiple strictures associated with enteroliths have also been reported [11, 12].

True enteroliths are less common, and are formed by the precipitation of material normally found in the GI tract (succus entericus). Calcium salts, such as the carbonate (CaCO3), the oxalate (CaC2O4), and the phosphate [Ca3(PO4) 2], are usually responsible for stone formation in the alkaline environment of the distal small bowel. These enteroliths are opaque and, if calcified, can be identified on X-ray. The basic underlying process in the development of true enteroliths is chronic stasis of intestinal contents, since peristalsis in a normal alimentary tract prevents the formation of significant concretions [13, 14]. As in our own case, the dilated and physiologically isolated segment of ileum became a reservoir of deoxycholate stones—an atypical finding which becomes understandable in light of the absence of normal bile acid absorption in ileum with Crohn′s disease.

The diagnostic modalities include abdominal X-rays, to provide evidence of stones in the abdomen outside common sites, such as the gallbladder or kidneys; ultrasound, to exclude or to confirm gallstone ileus; barium examination of the gastrointestinal tract, which may confirm the diagnosis; and CT, for possible confirmation of the diagnosis or to assist in the differential diagnosis between intestinal obstruction caused by enteroliths or another pathology. An intestinal obstruction caused by the formation of enteroliths in the jejunal diverticula is usually persistent and unresponsive to conservative treatment. Thus, in most cases, laparotomy is unavoidable.

The surgical strategy is to check the irregular communication between the gallbladder and the gastrointestinal tract [8, 14–16], the jejunal diverticula and for stones in the intestinal tract. The consensus management of enterolith ileus at laparotomy is to attempt to manually crush the enteroliths and milk their fragments into the colon, from where they can be ejected [7, 8, 17–20]. If this proves impossible, the stone can be removed through an enterotomy made in a less edematous area, proximal or distal to the obstruction site [7, 20]. If these two steps fail, the primary lesion containing the enterolith must be resected [9]. Resection of the involved bowel segment may be considered in patients with complicated enterolith ileus [7, 19, 20] or in those with complicated diverticulosis [21, 22]. In our patient, resection of the involved bowel segment was performed.

Based on our search of the literature, small intestinal obstructions secondary to enteroliths are rare. Fewer than 100 cases have been described in the literature [7, 14]. Table 1 shows the variety of causes that have been implicated for the formation of enteroliths. Most of these disease states lead to stasis or hypomotility. Other causes include jejunal diverticulosis and side-to-side small intestinal anastomosis. These anastomoses can have outpouchings or projections beyond the anastomosis that causes pooling of the intestinal contents [11]. This may subsequently lead to inspissation and enterolith formation. Moreover, we could not find any information on the possibility of the recurrence of enteroliths, probably because so few cases have been reported globally.

| Congenital | Meckel′s diverticulum |

|---|---|

| Duodenal diverticulum | |

| Aganglionosis | |

| Congenital diverticulosis | |

| Congenital webs | |

| Congenital diaphragms | |

| Congenital atresia | |

| Ileal duplication cysts | |

| Surgical causes | Afferent duodenojejunal loop postgastrojejunostomy |

| Bypassed intestinal loops | |

| H-shaped side-to-side bowel anastomoses | |

| Metabolic, foreign body, and medications | Hypercalcemia |

| Strictures and stenosis | Talc exposure, barium, different foreign bodies |

| Levodopa, antidiarrheals, morphine derivates, and others and medications | |

| Strictures and stenosis | Colonic stenosis |

| Small-bowel stenosis | |

| Chronic incarcerated hernias | |

| Strictures (i.e., tuberculosis) | |

| Inflammatory | Regional enteritis |

| Ulcerative colitis | |

| Tuberculous enteritis | |

| Nontropical sprue | |

| Other | Small-bowel diverticulosis |

In conclusion, enterolithiasis should be considered in any patient with Crohn′s disease who presents with intestinal strictures. The correct management of such a patient should be the removal of the enterolith and treatment of the underlying strictures by either strictureplasty and/or resection.