Clinical outcomes with ustekinumab as rescue treatment in therapy-refractory or therapy-intolerant ulcerative colitis

Abstract

Background

Recently, ustekinumab a monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin-12 and −23 and successfully used in Crohn’s disease also has been shown to be effective in induction and maintaining remission in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis in a large phase 3 trial. However, no observational data on the use of ustekinumab in ulcerative colitis in daily clinical practice is available.

Aim

The purpose of this study was to assess the clinical outcomes achieved with ustekinumab as rescue treatment in therapy-refractory or -intolerant ulcerative colitis in a real-life setting.

Methods

A retrospective data analysis was performed in 19 ulcerative colitis patients who were intolerant or refractory to all of the following drugs: steroids, purine-analogues, tumour necrosis factor antibodies and vedolizumab. To all patients ustekinumab was provided as a rescue treatment (intravenous induction with 6 mg/kg, followed by week subcutaneous injection once every eight weeks of 90 mg). The primary outcome was achievement of clinical remission at one year, defined as score of ≤ 3 points in the Lichtiger score (colitis activity index). Patients were evaluated regularly and a colonoscopy was performed before the start and at the end of the observation. Ethical approval was provided by Ethikkommission Ärztekammer Hamburg (PV 5539).

Results

In five patients, therapy was stopped due to refractory disease or side effects. In all remaining 14 patients the median colitis activity index dropped from 8.5 points (range 1–12) at start to 2.0 points at one year (range 0–5.5) and Mayo endoscopy scores fell from a median of two points (range 1–3, mean of 2.3) at start to a median of one point (range 1–3, mean of 1.4) at one year. Including the five drop-outs, clinical remission was achieved in 53% of the 19 patients at one year.

Conclusions

In accordance with the UNIFI (A Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Ustekinumab Induction and Maintenance Therapy in Participants With Moderately to Severely Active Ulcerative Colitis) trial our real-life data support ustekinumab as an effective and safe treatment option in therapy refractory moderate to severe ulcerative colitis with a history of biological therapies.

Key summary

- Ustekinumab has recently been shown being effective in induction and maintaining remission in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis (UC) in a large phase 3 trial.

- However, no observational data on the use of ustekinumab in UC in daily clinical practice is available.

What are the significant and/or new findings of this study?

- We showed in a real-world setting that ustekinumab is also effective in therapy-refractory or -intolerant UC outside clinical trials.

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that, despite the increasing use of immunosuppressants, immunomodulators and biologics, does still exert debilitating, humiliating and mutilating effects on patients.1,2 Although the advent of biologics like the anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-antibodies infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab, and more recently the anti-integrin-antibody vedolizumab, have substantially improved the therapeutic options in UC,3 mucosal healing rates are low and still 10–16% of patients lose their colon due to therapy-refractory situations.1,4 In addition, reluctance to use potent drugs earlier in the course of their disease5 and the structural damage due to ongoing inflammation6,7 could contribute to this dilemma.

Ustekinumab, the monoclonal antibody to the p40 subunit of interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23, has been approved8 for the use in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD), after its safety and efficacy has been shown in the UNITI trials.9,10 UNITI is the study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of Ustekinumab in patients with moderately to severely active Crohn’s Disease who have failed or are intolerant to tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy. Increased levels of IL-23 and T helper (Th)17 cell cytokines were found not only found in the intestinal mucosa, plasma and serum of patients with CD, but also those of patients with UC.11–13 IL-23-blocking has been shown to reduce the severity of inflammation in experimental colitis14–16 and hence been suggested for the use in UC.17

In September 2019, results of a large phase 3 clinical trial, the UNIFI (A Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Ustekinumab Induction and Maintenance Therapy in Participants With Moderately to Severely Active Ulcerative Colitis) trial were published.18 UNIFI was started in July 2015 and included a total of 961 UC patients demonstrating that ustekinumab is also effective and safe in induction and maintaining remission in patients with UC. Based on these results, ustekinumab was approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis in September 2019 and October 2019, respectively.

In 2016, neither pre-approval trials nor clinical observation data on the use of ustekinumab in UC were available. Since many of our patients with Crohn’s colitis and patients with indeterminate colitis showed good treatment results when they received ustekinumab, we planned an observational study using ustekinumab as rescue treatment in therapy-refractory or -intolerant UC and aimed to make our data accessible as soon as possible.19 We now present the long-term results of that observational study, including data on induction, maintenance and endoscopy at 12 months.

Methods

Patient population and design of the observational study

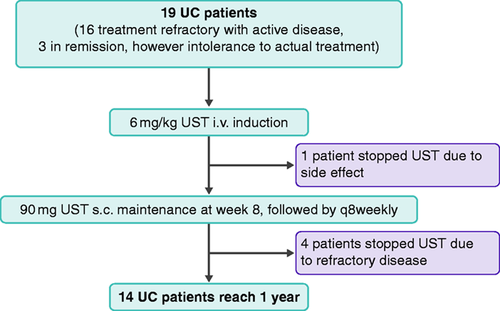

Our single centre, observational cohort study was performed at the IBD centre of Munich, Germany. The tertiary IBD centre of Munich is the largest IBD centre in the wider Munich area and services a catchment population of approximately two million people. All patients of the Munich IBD centre with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis who were steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent and who had recently failed or were intolerant to all of the following drugs, purine-analogues, anti-TNF-antibodies and anti-integrin-antibodies, and to whom colectomy had been offered as the only other option, were informed about their situation, the potential safety and efficacy data of ustekinumab and our plans to apply for ustekinumab as rescue medication. For those patients who were suitable and willing to participate in this observational trial, we applied for an off-label approval of the patients’ health insurance, which granted access to ustekinumab in 82% of cases; hence of 22 consecutive adult patients (≥18 years) with UC who were identified, 19 were able to receive ustekinumab (Figure 1).

Flow chart of 19 ulcerative colitis (UC) patients included in the observational trial. i.v.: intravenous; q8weekly: once every 8 weeks; s.c.: subcutaneous; UST: ustekinumab.

In order to participate and to be included into the observational trial, patients had to have a diagnosis of UC confirmed by conventional endoscopy at the IBD centre of Munich, had to be steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent and had failed or were intolerant to all of the following drugs: purine-analogues, anti-TNF-antibodies and anti-integrin-antibodies. Patients did either have a flare or were in remission, albeit having side effects or being steroid-dependent. Eligible patients gave written informed consent in order to participate. All patients had objective evaluation of their disease activity before starting ustekinumab (extensive internal medicine laboratory, including C-reactive protein (CRP) and calprotectin, and endoscopic and histologic evidence of inflammation).

The standard dosing regimen consisted of an intravenous (i.v.) induction with ustekinumab 6 mg/kg body weight, followed by a once every eight weeks (q8week) subcutaneous injection of 90 mg. Patients were evaluated after one month and later on at two, three, six, nine and 12 months. A control colonoscopy was performed between 40–50 weeks after the start of ustekinumab.

Disease severity was assessed using the Lichtiger score (=modified Truelove and Witts colitis activity index (CAI))20,21 including stool frequency, nocturnal diarrhoea, faecal incontinence, rectal bleeding, abdominal cramping and tenderness, general well-being and use of antidiarrhoeal drugs. Remission is defined as a Lichtiger score of three or less. Partial response is defined as a Lichtiger score of 4–10.

Video endoscopy was performed by one of three experienced gastroenterologists (CT, DS and TO) and findings on endoscopy were described using the Mayo endoscopic score:22 normal or inactive disease (zero points), mild disease (one point), moderate disease (two points) or severe disease (three points) The final agreement on the Mayo scoring was achieved by vote (CT, DS and TO). The study was approved by the ethical review board of the Ethikkommission der Ärztekammer Hamburg (PV 5539) of 17 April 2018. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the institution’s human research committee.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Nineteen patients with UC received ustekinumab (Figure 1) because their previous or recent long-term medications had either not induced an adequate clinical response (n = 16) or had resulted in intolerable side effects (n = 3). All patients had been treated with all of the following drugs: prednisolone, purine-analogues, anti-TNF-antibodies and anti-integrin-antibodies. One-quarter of the patients had also failed i.v. ciclosporine. Age and sex were well balanced and most patients had extensive UC (58%). The median and mean disease duration was five years, respectively. The baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

| Sex: | 8 women, 11 men |

| Age: | Range between 25–81 years, median 46 years |

| Mean time from first diagnosis | 5.3 years |

| Median time from first diagnosis (range) | 5 (2–15) years |

| Refractory or intolerant to all drugs (purine-analogues, TNF-antibodies, vedolizumab): | 19/19 (100%) |

| Medication, when ustekinumab was started: | |

| Vedolizumab: | 6/19 |

| Vedolizumab plus golimumab: | 4/19 |

| Vedolizumab plus azathioprine: | 3/19 |

| Vedolizumab plus ciclosporine: | 2/19 |

| Infliximab: | 3/19 |

| Azathioprine: | 1/19 |

| Steroid therapy, when ustekinumab was started: | 9/19 |

| Refractory to infliximab plus either golimumab or adalimumab: | 8/19 (42%) |

| Refractory to i.v. ciclosporine: | 5/19 (26%) |

| Patients in active disease (CAI>3: median 8.5, (range 4–12), mean 7.9): | 16 of 19 (84%) |

| Patients in remission (CAI<4 points: 1, 2, 3, respectively): | 3/19 (16%) |

| Extension of inflammation: | |

| Extensive (E3) pancolitis or proximal to left flexure: | 11/19 (58%) |

| Rectum to left flexure (E2): | 7/19 (42%) |

| Rectum only (E1): | 0/19 (0%) |

| Median Mayo endoscopic subscore at baseline in 19 patients: | 2 (range 1–3) |

- CAI: colitis activity index; i.v.: intravenous; TNF: tumour necrosis factor.

Outcomes

Dropouts and adverse events

A total of 19 UC patients were treated with ustekinumab (Figure 1) and all patients received ustekinumab as approved for CD (6 mg/kg as an infusion and 90 mg ustekinumab as subcutaneous (s.c.) injection q8w). At the start of ustekinumab, all other maintenance drugs (azathioprine, ciclosporine, golimumab, infliximab or vedolizumab, respectively) were stopped. Tapering of steroids was attempted in all patients.

In four patients, therapy was stopped due to refractory disease at three months (one patient), six months (one patient) and nine months (two patients), and in one patient therapy was stopped due to drowsiness at week 4. Of those five patients who stopped ustekinumab, two underwent colectomy and three received other study medications.

In one woman, breast cancer was diagnosed after the induction dose; she received surgery, chemo- and hormonal therapy and wished to continue on ustekinumab (q8w) due to its good effect on her UC. In another woman we found rectal adenoma during the last colonoscopy. One woman developed otitis media at six months and was successfully treated with antibiotics; another woman developed lateral pharyngitis at nine months, which resolved without treatment. One male patient developed a sudden hearing loss that resolved after treatment, another male patient experienced a new diagnosis of atrial fibrillation at six months. One patient developed retinal detachment at six months. All these patients continued with ustekinumab.

Patients continuing therapy

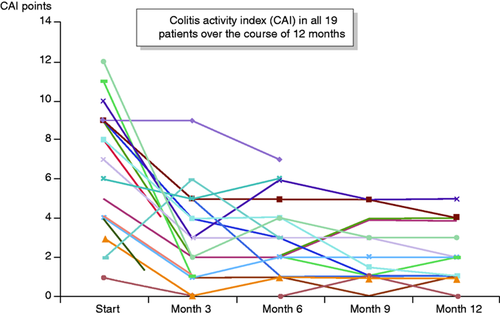

Hence, 14 of 19 patients continued with ustekinumab. They all reached 12 months of observation and all received a total colonoscopy. Among those 14 patients, the median CAI dropped from 8.5 points (range 1–12) at start to 2.5 points (range 0–5) at three months, 2.5 points (range 0–6) at six months and 1.8 points at nine months (range 0–5) and 2.0 points at 12 months (range 0–5.5).

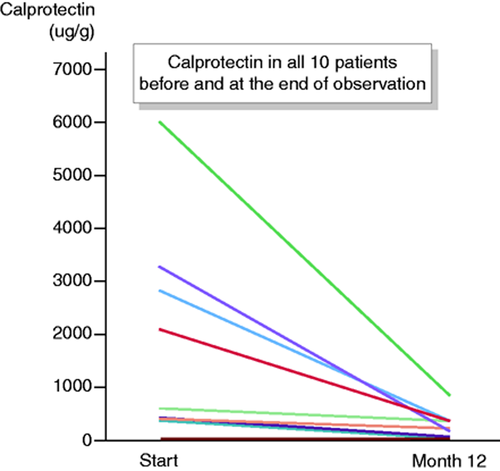

The median faecal calprotectin dropped from 428 ug/g (range 165–6000) to 236 ug/g (range 97–6000) at three months, 316 ug/g (range 84–3161) at six months, 260 ug/g (range 63–1596) at nine months and 244 ug/g (range 28–1443) at 12 months.

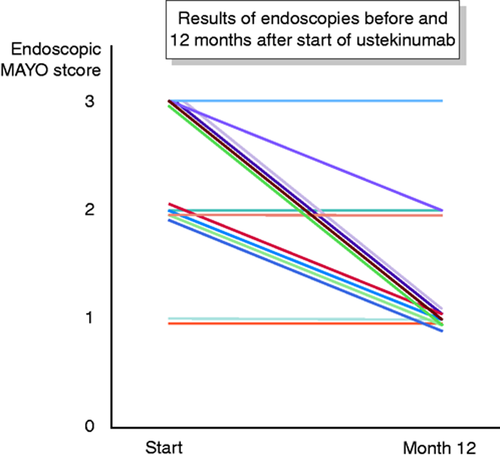

Mayo endoscopy scores fell from a median of two points (range 1–3, mean of 2.3) at the start of the observation to a median of one point (range 1–3, mean of 1.4) at 12 months (Figure 2). Ten of 14 (71%) patients who were continuously treated with ustekinumab achieved a Mayo score of one at 12 months.

Endoscopic results in all 14 patients who continued ustekinumab up to at least one year.

Overall outcome

Of all 19 patients, 16% (3/19) were in remission (CAI < 4) at the start of the observation. At 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months, clinical remission was observed in 37% (7/19), 58% (11/19), 58% (11/19), 53% (10/19) and 53% (10/19) of patients, respectively (Figure 3). Of all 10 patients who were in clinical remission at one year, the median calprotectin has dropped from a median of 516 ug/g (mean 1645 ug/g; range 30–6000) to 186 ug/g (mean 242 ug/g; 28–810), (Figure 4).

Clinical outcome as measured by Lichtiger score (colitis activity index (CAI))21,22 in all 19 patients throughout one year.

Calprotectin in all 10 patients who were in remission at one year, measured at the start and at one year.

At three, six, nine and 12 months, all but one of these patients who were in remission, were also free of steroids, although nine of them started with steroids.

Of the three patients who already were in remission and who were intolerant to their previous medication, ustekinumab was able to maintain remission in two patients up to 12 months ((a) patient: CAI from one to zero points; (b) patient: CAI from three to one points; (c) patient: stopped).

Patients with active disease

Of 16 patients with active disease at the start of the observation, four patients were in clinical remission (CAI < 4) at one month (25%) and eight patients (50%) at three, six, nine and 12 months, respectively. Of those eight patients who had active disease in the beginning and who were in clinical remission at the end of the observation, four patients had achieved clinical remission at one month, two patients at two months, one patient at three months and another patient later than six months.

Discussion

Effect of ustekinumab in therapy refractory UC in a real-life setting

The findings of our observational real-life study confirm the results of the UNIFI study18 that ustekinumab is an effective treatment option in patients with moderate to severe UC. We showed that 50% of patients with active moderate or severe UC who were at least refractory or intolerant to purine-analogues, TNF-blockers and the anti-integrin vedolizumab, can still be brought into remission with ustekinumab, applied in the same dosing regimen as in Crohn’s disease. Of 16 patients with active disease at the start of the observation, ustekinumab brought eight patients into remission at three, six, nine and 12 months, respectively. Of the three remaining patients who already were in remission at the start, but were switched to ustekinumab due to intolerance to the previous medication, two could be kept in remission at 12 months.

This observed clinical remission was accompanied by a reduction of the median faecal calprotectin from 428 ug/g (range 165–6000) at the start to 244 ug/g (range 28–1443) at 12 months and a drop of the median Mayo endoscopy scores from two points (range 1–3) at the start to one point (range 1–3) at 12 months (Figure 2). These results are underlined by the fact that at 12 months 71% of patients (10 of 14) who were continuously treated with ustekinumab achieved a Mayo endoscopy score of one, which is generally acknowledged as endoscopic remission. In addition, all but one of all 10 patients who were in remission, were also free of steroids at three, six, nine and 12 months, although nine of them started with steroids.

Effect of ustekinumab compared to the results in the UNIFI trial

Despite the small study size of 19 patients, the observational character of our study, and a scoring system that has never been validated, which all limit the validity and quality of our study, the outcome was quite surprising: Reaching clinical remission as well as endoscopic remission in more than 50% of refractory UC patients is remarkable in patients who were refractory or intolerant to all immunomodulators. Hence, our findings are comparable to the results of the UNIFI trial.18 In UNIFI, reported clinical remission rates at week 44 were 38.4% for patients receiving 90 mg ustekinumab s.c. every 12 weeks, as compared to 43.8% for patients with 90 mg ustekinumab s.c. every eight weeks and 24.0% in the placebo group. Although, one has to take into account that in UNIFI only responders were carried on in the maintenance trial, and therefore the actual percentage of patients who started ustekinumab and reached clinical remission at week 44 presumably was even lower. In addition, only approximately 18% of UC patients in the UNIFI trial were refractory or intolerant to anti-TNFs and vedolizumab. Furthermore, approximately 50% of UC patients in the UNIFI trial receiving q8w ustekinumab showed endoscopic improvement at week 44 (defined as a Mayo endoscopic subscore of zero or one), a result similar to our findings.

Confounders

The open and unblinded study design is prone to bias. However, the fact that in those 10 patients, who were in clinical remission at one year, the calprotectin had profoundly dropped from a mean of 1645 ug/g to a mean of 242 ug/g (Figure 4), and the fact that 71% (10 of 14) patients, who were continuously treated with ustekinumab, achieved a Mayo score of one at 12 months, substantiate the outcome of our observation. This effect is further underscored by the fact that nine of 10 patients who were in remission, were also free of steroids at three, six, nine and 12 months, although nine of them started with steroids.

Another possible bias in terms of patient selection might be found in the interesting fact that all 10 patients who were in remission at the end of the study were started on ustekinumab (Table 1) when they were still under the influence of vedolizumab which had just been stopped (15 of 19 patients received vedolizumab as the last drug before ustekinumab). Gut-selective blocking of lymphocyte trafficking into the mucosa might not have exerted sufficient anti-inflammatory properties within the mucosa in the subset of our UC patients. The Erlangen study group has recently shown23 that patients with IBD who show no remission to vedolizumab therapy exhibit distinct genetic signatures, which are characterised by the upregulation of genes that mediate mucosal inflammation in IBD patients. They revealed a strong activation of TNF-dependent signalling pathways in non-remitters to vedolizumab treatment, thereby suggesting that anti-TNF therapy might be a therapeutic option in IBD patients with vedolizumab failure. However, among those genes significantly upregulated in UC patients with no remission to vedolizumab, many of them were also involved in the upregulation of the p40 containing cytokine IL-23.23 Hence, due to its assumed up-regulation, blocking IL-23 with ustekinumab in our patients might have been an important step to suppress immune cell activation and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, like IL-17, IL-17 F, IL-6 and TNF.24 Future studies will be able to analyse these correlations, because after the global approval for the treatment of UC, many patients who fail TNF-blocking antibodies or vedolizumab or both will be treated with ustekinumab as second or third antibody.

Safety

With respect to safety, one breast cancer was reported in one woman and a newly emerged rectal adenoma in another female patient. However, no deaths, serious opportunistic infections or major adverse cardiovascular events were reported. The safety signals of our observation are consistent with the known safety profile of ustekinumab in CD9,10 and the latest safety data in UC patients from the UNIFI trials.18 Regarding the malignancy risk of ustekinumab, large pooled data analyses from psoriasis studies followed-up through up to five years indicated no increased malignancy risk compared with the general population.25 More recent pharmacovigilance data from the US FDA and European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Pharmacovigilance (EudraVigilance) database for the European Union, however, detected a safety signal for malignancies in patients treated within ustekinumab between 2001–2016, i.e. predominantly in patients with psoriasis.26 Prospective long-term trials, pharmaco-epidemiological studies and registries are necessary to determine if an increased risk for malignancy is associated with ustekinumab in patients with UC and CD who are treated with ustekinumab at doses noticeably higher than in psoriasis.

In summary, in our small observational and descriptive real-world study, patients with moderate or severe UC who were therapy-refractory or -intolerant did benefit from ustekinumab. They reached clinical as well as endoscopic remission in more than 50% of all cases. This observation is in accordance with the remission rates that have recently been published in the UNIFI study, which has led to the approval of ustekinumab for the treatment of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis in September 2019.

We conclude that ustekinumab can be established as an effective and safe treatment option in patients suffering from moderate to severe ulcerative colitis.

Author contribution

Thomas Ochsenkühn, Cornelia Tillack and Daniel Szokodi performed the research, collected and analysed the data, designed the research study and wrote the paper. Shorena Janelidze collected and analysed the data; Fabian Schnitzler analysed the data and wrote the paper.

Declaration of conflicting interests

Thomas Ochsenkühn has received travel grants, honoraria for advisory activities and lecture fees from Janssen. Fabians Schnitzler has received honoraria for advisory activities and lecture fees from Janssen. All other authors have no conflicts to declare.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the ethical review board of the Ethikkommission der Arztekammer Hamburg (PV 5539) of 17 April 2018.

Funding

No specific funding has been received for this work.

Informed consent

All patients gave written informed consent in order to participate.