Endoscopic papillectomy for neoplastic ampullary lesions: A systematic review with pooled analysis

Abstract

Endoscopic papillectomy (EP) is a viable therapy in ampullary lesions (AL). Many series have reported low morbidity and acceptable outcomes. We performed a systematic review with pooled analysis to assess the safety and efficacy of EP for AL. Electronic databases (Medline, Scopus and EMBASE) were searched up to September 2018. Studies that included patients with endoscopically resected AL were eligible. The rate of adverse events (AEs; primary outcome) and the rates of both technical and clinical efficacy outcomes were pooled by means of a random- or fixed-effects model to obtain a proportion with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Twenty-nine studies were included (1751 patients). The overall AE rate was 24.9%. The post-procedural pancreatitis rate was 11.9%, with the only factor affecting this outcome being prophylactic pancreatic stenting. The complete resection rate was 94.2%, with a rate of oncologically curative resection of 87.1%. The recurrence rate was 11.8% (follow-up: 9.6–84.5 months). EP is a relatively safe and effective option for AL. Our study might definitively suggest the protective role of prophylactic pancreatic stenting against post-procedural pancreatitis.

Introduction

Ampullary adenomas are rare entities, with a prevalence of 0.1% in autopsy studies.1 Symptoms are usually related to pancreatico-biliary obstruction,2 but diagnosis can also be made in asymptomatic patients undergoing a upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy.3 When detected, ampullary tumours should be removed completely because 30% of benign adenomas transform into malignant carcinoma.4,5 Moreover, forceps biopsies of ampullary lesions revealed an alarming 30% of false-negative in detecting carcinoma.6 Historically, surgery has had a pivotal role in treatment. Nevertheless, the high mortality and morbidity rates of pancreatoduodenectomy (PD)7 and the high recurrence rate of surgical papillectomy (26–43%)8–10 have made endoscopic papillectomy (EP) the preferred treatment for benign and non-invasive ampullary tumours. In fact, high-quality recommendations have never been established, and many issues still persist, including the optimal papillectomy technique and strategies to reduce both recurrences and adverse events.

Several prospective and retrospective series have been published, but data on efficacy and safety of EP have never been systemically reviewed. The aim of this paper was to perform a pooled analysis of EP procedures in order to give a comprehensive view on this topic.

Methods

The methods of our analysis and inclusion criteria were based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations.11 Our systematic review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/) in December 2018 (registration number: CRD42019118709). The following methods are reported in Appendix 1: data sources and search strategy, the selection process, inclusion and exclusion criteria, data extraction, the quality assessment, outcomes assessment, outcomes definitions and statistical analysis.

Results

Study characteristics and quality

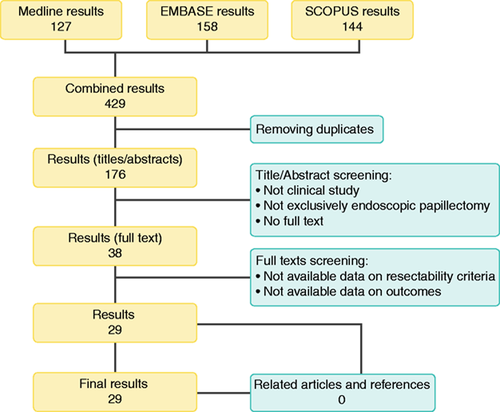

The literature search resulted in 429 articles (Figure 1). After reviewing the title and abstract, 38 articles were retrieved as full text. Of these, 29 articles matched the selection criteria and were finally included in the analysis.12–41 Study characteristics and quality are comprehensively reported in Appendix 3. The baseline characteristics of the 1751 included patients are provided in Table 1.

Flow chart of the study selection process.

| Characteristic | Pooled estimate (95% CI) | Heterogeneity (I 2) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean tumour size, mm | 15.7 (13.1–18.3) | 97% |

| Mean age, years | 60.2 (56.9–63.5) | 93% |

| Sporadic lesion/familial predisposition | ||

| Sporadic lesions (proportion) | 66.8% (52.5–81.0%) | 97.3% |

| Symptoms onset (proportion) | ||

| Jaundice | 16.6% (7.1–26.0%) | 97.6% |

| Pain | 14.4% (6.9–21.9%) | 98.7% |

| Cholangitis | 1% (0.3–1.6%) | 13.2% |

| Pancreatitis | 4.1% (1.9–6.3%) | 85% |

- CI: confidence interval.

Adverse events

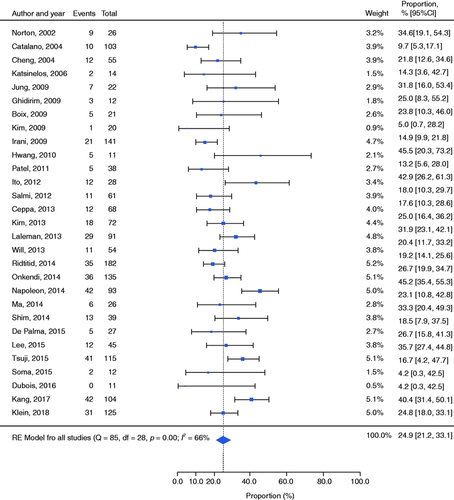

Based on the data reported in all 29 studies, 407 EP had an adverse event, yielding a pooled complication rate of 24.9% (21.2–29.0; I 2 = 66%; Figure 2), with none of the analysed factors affecting this outcome on univariate meta-regression (see Supplemental Table S1 for details).

Forest plot reporting the rates of adverse events. CI: confidence interval; RE: random effects.

In particular, the calculated pooled rates of procedure-related cholangitis and perforations were 2.7% (1.9–4.0; I 2 = 32%) and 3.1% (2.2–4.2; I 2 = 17%), respectively. Further, bleeding occurred in 197 cases of endoscopic resections, with a pooled rate of 10.6% (5.2–13.6; I 2 = 61%; Supplemental Figure S1). Across the 16 studies reporting any need for a blood transfusion, 33/121 patients with procedural-related bleeding required at least one blood unit.

Further, 23 studies (156 events) reported how the bleeding was managed: six patients required angiography and embolisation, and one patient was referred for surgery. The remaining patients were treated conservatively.

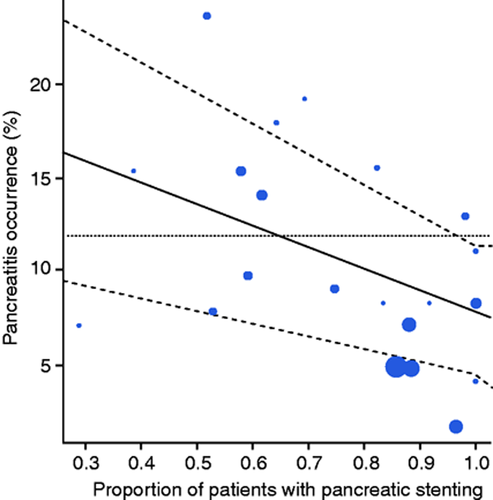

The rate of post-procedural pancreatitis was 11.9% (10.4–13.6; I 2 = 41%; Supplemental Figure S2), with 18/187 patients being reported as severe.42 On univariate meta-regression, the only factor affecting this outcome was the same-session prophylactic pancreatic stent placement (odds ratio (OR) = –1.72; confidence interval (CI) –2.95 to −0.50; p = 0.006; see Supplemental Table S2 and Figure 3 for details). Nevertheless, it did not significantly affect the overall rate of adverse events (OR = −0.55; p −0.386). The subgroup analysis on placing prophylactic pancreatic stenting or not is reported in Appendix 3.

Bubble plot reporting the association between post-procedural pancreatitis occurrence and the proportion of patients with pancreatic stenting.

Finally, considering late adverse events, 10 papillary stenosis occurred after papillectomy, yielding a pooled rate of 2.4% (1.6–3.4; I 2 = 0%). A subcategorised analysis of papillary stenosis could not be done due to limited data.

Across all the 29 studies, 11 patients were referred for surgery because of a severe adverse event. Finally, among all 1751 lesions, there were six procedure-related deaths. An overview of the main safety outcomes is reported in Supplemental Table S3. Publication bias on primary outcome is reported in Appendix 3.

Technical success

The complete resection rate was reported in 24/29 studies. Overall, the pooled rate of EP on 1300 ampullary lesions was 94.2% (90.5–96.5; I 2 = 73%). Among the studies reporting the need for any same-session adjunctive therapy to have the lesions completely removed, a pooled rate of 36.1% (21.5–53.9; I 2 = 92%) was reported. Further, 18 studies reported a rate of en-bloc resection as an outcome. The pooled en-bloc resection rate across these studies was 82.4% (74.7–88.1; I 2 = 84%).

Oncologic success

The curative resection rate after EP was 87.1% (83.0–90.3; I 2 = 70%) in 1589 ampullary lesions (27 studies). On univariate meta-regression, the only factor affecting the curative resection rate was the rate of en-bloc resections (OR=3.55; CI 1.11–5.99; p = 0.004; see Supplemental Table S4 and Supplemental Figure S3 for details). An overview of the main resection outcomes are reported in Supplemental Table S5. Follow-up outcomes were reported in Appendix 3.

Sensitivity analysis

The results of the pooled analysis focused on the 14 studies enrolling at least 50 patients are reported in Table 2. Patient and lesion characteristics are summarised in Supplemental Table S6.

| Variable | Pooled estimate | I 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Safety outcomes | ||

| Bleeding | 11.0% | 74% |

| Cholangitis | 2.0% | 32% |

| Perforation | 2.8% | 17% |

| Papillary stenosis | 2.0% | 0% |

| Pancreatic stenting | 79.6% | 95% |

| Pancreatitis | 11.4% | 41% |

| Pancreatitis (stenting) | 5.9% | 0% |

| Pancreatitis (no stenting) | 18.2% | 0% |

| Overall adverse events | 24.4% | 81% |

| Efficacy outcomes | ||

| Complete resection | 93.8% | 84% |

| En bloc | 76.1% | 93% |

| Curative resection | 86.5% | 74% |

| Recurrences | 11.3% | 78% |

| Endoscopic retreatment | 5.8% | 74% |

| Endoscopically managed | 79.8% | 89% |

| Definitive treatment | 73.2% | 89% |

Discussion

EP for ampullary lesions was first reported as a series in 1993 by Binmoeller et al.,43 with the promise of decreased morbidity and mortality compared to PD and surgical papillectomy. Since then, the endoscopic approach with curative intent has gained an increasing role as an alternative to surgery. However, the perceived risk of complications is still a major barrier for EP for being considered the first choice for managing ampullary lesions. Moreover, while several studies on EP have been published, the single-centre setting paired with the retrospective design of most of them has prevented high-quality recommendations being reporting on this topic.

This systematic review and pooled analysis of the available literature is the first effort to provide comprehensive data on the results of EP and to highlight the gaps in current knowledge. According to our analysis, both the efficacy and safety of EP are encouraging for ampullary lesions, as shown by the 80.9% rate of lesions effectively managed in an endoscopic fashion with only an anecdotal risk of death.

The lack of high-quality studies comparing endoscopic and surgical approaches for ampullary lesions prevents a direct comparison. However, in term of safety, considering surgery alone, Bourgouin et al. previously showed a mortality rate of 8.9% after PD for ampullary and peri-ampullary tumours and a risk of severe adverse events of 26.7%.44 Further, Lai et al. reported the PD-related morbidity and mortality rates to be 50.6% and 9.7%, respectively.45

After 1751 EP, we found the overall rate of adverse events to be 24.9%, with deaths occurring in six cases. As expected, the most frequent AE was post-procedural pancreatitis, with a pooled rate of 11.9%, with most of those being mild or moderate. Previously, some investigators have proposed prophylactic pancreatic stenting to reduce the risk of post-procedural pancreatitis. Its protective effect was also confirmed in a randomised controlled trial by Harewood et al. in 2005.46

Indeed, one of the main findings of our study is the rates of post-procedural pancreatitis varying significantly in the subgroup analysis based on whether a prophylactic pancreatic stent was placed after resection. Further, the pancreatic stent placement itself was confirmed to be the only factor significantly affecting the risk of pancreatitis on univariate meta-regression with reduction in the risk. This was also confirmed by the sensitivity analysis across the 14 studies, including more than 50 patients.

In some patients, however, a stent cannot be easily placed after snare excision because pancreatic duct cannulation may be difficult due to oedema or bleeding. The need for greater manipulation of the papilla may increase the risk of pancreatitis in a subgroup of patients. Different approaches have been proposed to facilitate pancreatic stent insertion. However, the optimal technique has yet to be found. Moreover, the recent development of adjunctive prophylactic measures to prevent post-procedural pancreatitis needs to be taken into account. In fact, both the use of rectal indomethacin and the administration of Ringer’s lactate solution are accepted measures and may contribute to reducing the risk of pancreatitis in this setting.

While routine pancreatic stenting should be recommended, the evidence for biliary stent placement is still weak. Cholangitis as well as papillary stenosis after EP proved to be rare events in the pooled analysis (2.7% and 2.4%, respectively), and a subgroup analysis of the role of biliary stenting could not be done due to limited data. In our opinion, prophylactic biliary stenting may be considered in a subgroup of patients at high risk for developing cholangitis or biliary stenosis (i.e. not dilated bile duct, need for aggressive hemostasis for intraprocedural bleeding, high risk of delayed bleeding and haemobilia17). However, conclusive evidence for these indications is still lacking.

Focusing on procedure-related bleeding, a pooled rate of 10.6% was reported. As already underlined for pancreatitis severity, most cases of bleeding were mild to moderate, not requiring any blood transfusion or aggressive therapeutic approaches such as embolisation or surgery. However, because of the frequency of adverse events, most studies perform all of the EP procedures as an inpatient procedure.

The second focus of our analysis was the efficacy profile, suggesting the feasibility of EP as the first therapeutic choice for ampullary lesions, as shown not only by the good technical success (94.2% of complete resection and 82.4% of en-bloc resection rates), but also by the oncological outcomes. A curative resection rate of 87.1% coupled with a rate of recurrence of 11.8% mean that 72.5% of lesions were definitively managed through a single endoscopic session and did not need any adjunctive therapeutic approach. Moreover, several patients benefited from further endoscopic procedures for being considered as oncologically cured (up to 80.9%). Despite the significant level of heterogeneity which prevents definitive quantitative conclusions in term of efficacy, EP may undoubtedly have spared high morbidity/mortality surgeries in a significant percentage of patients. Nonetheless, most studies have several limitations in reporting follow-up outcomes. Despite most studies explicitly including scar biopsies in the follow-up protocol, most are still retrospective, and none reports outcomes distinguishing between patients with sporadic or familiar lesions. Although the sporadic or familial nature of the ampullary lesions does not influence the procedural safety, of course these lesions modify both the risk of recurrence and the target we aim to reach. In fact, in sporadic adenomas, we would like to have a definitive cure, with no adenomatous tissue at follow-up biopsy, while in FAP patients, sometimes it could be a palliative strategy.

Further, one of the critical issues in the management of these lesions is the indication. Nevertheless, specific criteria are not yet fully established. Taking into account the pivotal importance of this still controversial point, we considered for inclusion only those studies explicitly stating their resectability criteria and the diagnostic pathway to assessing them. Summarising the criteria reported in the included studies, we have derived the following contraindications for EP: features of malignancy at endoscopic view (friability, rigidity and ulceration) and intra-ductal extension of >1 cm. Size per se may need to be considered as a strict contraindication for endoscopic resection. However, resecting lesions in an en bloc fashion was found to affect the rate of curative resection. Indeed, size may be taken into account when balancing the pros and cons of an endoscopic approach.

This is the first comprehensive pooled analysis to assess the cumulative efficacy and safety of EP. The main strength of our study is the considerable sample size of more than 1700 ampullary lesions resected, permitting a more reliable and clinically relevant inference compared to any of the individual studies published previously. The biggest limitation was the high level of inter-study heterogeneity of some of the reported outcomes. Nevertheless, no considerable heterogeneity affected our main findings in terms of safety, even permitting strong behavioural recommendations on most adequate technical modalities for EP (i.e. prophylactic pancreatic stenting). Further, even being aware of the retrospective design of several studies might have brought about some biases, since most studies directly focused on adverse events, the risk of biased results remained low. Conversely, considering efficacy, based on this systematic review, we do not feel confident in giving conclusive statements, as the limitations of our analysis reflect the limitations of the current literature on this topic.

Despite these limitations, considering the relatively low rate of adverse events compared to surgery and the rare cases of death, we believe that this technique holds the potential to aid in avoiding high-risk surgery without increasing the oncological risk. The importance of sparing surgery needs to be considered as an aim in this setting because most papillary tumours are progress slowly, and most patients are elderly and are often borderline/unfit for surgery. However, to ensure the best results for patients, EP should always be performed by skilled endoscopists in tertiary centres with access to surgical and interventional radiology support for the management of adverse events.

Further studies designed and powered to prove the oncological efficacy of the endoscopic approach will be fundamental. Taking advantage of the comprehensive point of view of our systematic review, we facilitated a vision on what is actually needed in terms of scientific evidences for EP. Supplemental Table S7 summarises the key aims of future prospective studies.

In conclusion, EP appears to be a relatively safe alternative to surgery as the first therapeutic option for resecting ampullary lesion. Although the optimal technique for placing a pancreatic stent safely following EP is still under debate, our study might definitively suggest the protective role of prophylactic pancreatic stenting. Further high-quality studies are still needed to prove oncologic efficacy definitively.

Declaration of conflicting interests

None declared.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Supplemental material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.