Percutaneous-transhepatic-endoscopic rendezvous procedures are effective and safe in patients with refractory bile duct obstruction

Abstract

Background

Percutaneous-transhepatic-endoscopic rendezvous procedures (PTE-RVs) are rescue approaches used to facilitate biliary drainage.

Objective

The objective of this article is to evaluate the safety and the technical success of PTE-RVs in comparison with those of percutaneous transhepatic cholangiographies (PTCs).

Methods

Percutaneous procedures performed over a 10-year period were retrospectively analyzed in a single-center cohort. Examinations were performed because of a previous or expected failure of standard endoscopic methods including endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) or balloon-assisted ERC to achieve biliary access.

Results

In total, 553 percutaneous procedures including 163 PTE-RVs and 390 PTCs were performed. Overall, 71.3% of the patients suffered from malignant disease with pancreas-carcinoma (32.8%) and cholangio-carcinoma (19.0%) as the most frequent, while 28.7% of the patients suffered from benign disease. Many patients had a postoperative change in bowel anatomy (50.8%).

PTC had a higher technical success rate (89.7%); however, the technical success rate of PTE-RVs was still high (80.4%; p < 0.003). Overall complications occurred in 23.5% of all procedures. Significantly fewer complications occurred after performing PTE-RVs than after PTCs (16.6% vs 26.4%; p = 0.037).

Conclusion

Beside a high technical efficacy of PTE-RVs, significantly fewer complications occur following PTE-RVs than following PTCs; thus, PTE-RV should be preferred over PTC alone in selected patients.

Key summary

Established knowledge

- Percutaneous-transhepatic-endoscopic rendezvous procedures (PTE-RVs) remain rescue approaches for biliary interventions.

New findings

- Percutaneous-transhepatic-endoscopic rendezvous procedures (PTE-RVs) offer a high technical success rate (80%) in patients with a previously failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiography, including patients with an altered gastrointestinal tract.

- Significantly fewer complications occur following PTE-RVs than following percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) (16.6 vs 26.6%; p = 0.037); thus, PTE-RVs should be preferred over PTC alone in the case of a necessary percutaneous procedure for biliary interventions.

Introduction

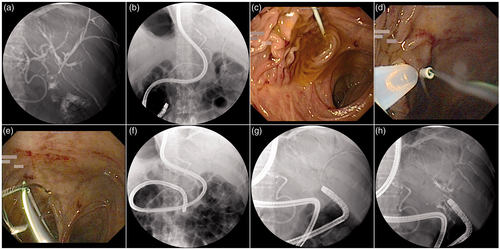

Biliary diseases, including bile duct obstructions, are routinely treated by endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC); however, if ERC fails, percutaneous transhepatic procedures remain rescue approaches despite the recent technical advancements of ERC technique in 4% to 5% of cases.1-5 In addition to the well-established percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) procedure, the percutaneous-transhepatic-endoscopic rendezvous procedure (PTE-RV), which combines the endoscopic technique with PTC, was introduced more than 20 years ago (Figure 1).6-8 PTE-RVs allow physicians to use only small-caliber catheters for the transhepatic puncture and provide all the advantages of endoscopic therapy including the performance of endoscopic-guided sphincterotomy, the endoscopic removal of stones and the endoscopic placement of larger-caliber endoprostheses.1,6

Imaging of a performed percutaneous-transhepatic-endoscopic rendezvous procedure (PTE-RV). (a–c) Guidewire placement via the transhepatic route into the intestinal lumen was performed. The conventional endoscopic intubation of the afferent limb with a single-balloon enteroscope failed. (d–h) An endoscopic snare was used to catch the transhepatic guidewire; thus, the endoscope could be advanced into the afferent limb up to the biliodigestive anastomosis to complete the RV procedure.

To date, few studies have evaluated the efficacy and safety of PTE-RVs; however, most studies reported only a few procedures, ranging up to 40 procedures, and all studies failed to directly compare the safety rates between PTE-RVs and standard PTC.9-13 The lack of evidence concerning the safety and technical success rates of RV procedures is surprising because this technique has been known for years. The recently published clinical guidelines of the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) concerning papillary cannulation at ERC states, that “when biliary cannulation is unsuccessful with a standard approach, anterograde guidewire insertion by percutaneous-guided approach can be used to achieve biliary access”; owing to the lack of studies, this statement is based on low-quality evidence.14

To address the lack of evidence, the aims of this study were to evaluate the safety and technical success of PTE-RVs using the largest available data set and compare this to standard PTC.

Methods

Study design

This retrospective study was performed at the Department of Medicine B for Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the University Hospital Münster, Germany. The study was approved by the Medical Council of Westphalia-Lippe and the ethics board of the Westphalian Wilhelms-University of Münster, Germany (date of approval: December 21, 2017). This study conforms to the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in the prior approval by the institution's human research committee. As approved by the ethics board, informed patient consent was not required for this study because of its retrospective design. Data from 244 patients ≥ 18 years of age who underwent a percutaneous procedure, including PTE-RVs and PTCs, over a 10-year period (January 2003 to December 2013) were retrieved from the clinical data system. Patients received a percutaneous procedure because of a previous or expected failure of endoscopic techniques including standard ERC and/or balloon-assisted ERC to achieve access to the biliary tract. Frequent reasons for a failure of standard endoscopic examinations were postoperative changes of the bowel anatomy with a failure to cannulate the papilla of Vater, nontraversable biliary or gastrointestinal strictures and alterations of the papilla of Vater. The choice of percutaneous procedure (PTE-RV or PTC) was up to the performing endoscopists: For example, PTCs were performed in cases of nontraversable gastrointestinal strictures, while PTC-RVs were preferred in cases of a failure to cannulate the papilla of Vater. Examinations were carried out by at least by two endoscopists who had a great level of experience performing percutaneous transhepatic procedures; alternatively, if one examiner had minor experience performing percutaneous transhepatic procedures, he was directly supervised by an experienced endoscopist.

Technical success of percutaneous procedures

The technical success of PTC was defined as the establishment of a percutaneous access to the biliary tract allowing a subsequent intervention to establish biliary drainage. The technical success of the RV procedures was defined as the establishment of an intestinal access to the biliary tract using a PTE-RV procedure allowing a subsequent intervention to establish biliary drainage (Figure 1).

Safety analysis

Adverse events were subdivided into procedure-related complications and drainage-related complications. Procedure-related complications were diagnosed as follows: a) acute pancreatitis, peritonitis and cholangitis were defined as systemic inflammatory reactions: specifically, postinterventional pancreatitis was diagnosed if the onset of abdominal pain was accompanied by a three-fold increase in the serum lipase levels within 48 hours of examination, postinterventional cholangitis was defined as the onset of fever (body temperature above 38.0 °C within seven days of the examination) and new or significantly higher inflammation markers requiring antibiotics following examination, and peritonitis was diagnosed based on abdominal pain, elevated inflammation markers and imaging reports; b) major bleeding was diagnosed by endoscopists based on a diagnosis of procedure-related hematoma using abdominal ultrasound the following day and/or a significant decrease in hemoglobin (at least 2 g/dl); c) pulmonary complications such as pneumothoraxes were diagnosed using chest X-rays or thoracic computer tomography imaging; d) anesthesia-related complications were diagnosed by endoscopists and/or anesthesiologists using a standard examination protocol; e) liver biloma were diagnosed based on the clinical presentation of the patient and abdominal imaging; and f) all other complications were documented. In addition to procedure-related complications, drainage-related complications (e.g. drainage dislocation, drainage occlusion) were documented and subdivided into the following categories: a) drainage complications within one week after the intervention and b) drainage complications occurring > 1 week and ≤1 month after the intervention.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). The contingency table-derived data were calculated using the StatPages website.15

Results

Study population

In total, we performed 553 percutaneous procedures, including 163 PTE-RVs and 390 PTCs in 244 patients. Our study cohort had a median age of 67 years (interquartile range: 58–76 years) and was predominantly male (63.5%). In total, 71.3% of the patients had a diagnosis of malignancy, and nearly half of these patients suffered from metastatic disease (48.9%). The most frequent malignancy was pancreatic carcinoma (32.8%), followed by cholangio-carcinoma (19.0%) and gastric-carcinoma (17.8%). In total, 28.6% of the patients had a benign diagnosis (28.6%), and cholelithiasis (45.7%) and postoperative biliodigestive anastomotic strictures (31.4%) were the most frequent conditions. A total of 50.8% of the patients had a postoperative change of the bowel anatomy (Table 1).

| Variables | Patients (n = 244) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67 (58–76) |

| Female (%) | 89 (36.3) |

| Male (%) | 155 (63.5) |

| Number of percutaneous procedures | 553 |

| PTE-RV | 163 (29.5) |

| PTC | 390 (70.5) |

| Main diagnosis (%) | |

| Malignancy | 174 (71.3) |

| Metastatic disease | 85 (48.9) |

| Entities of carcinoma | |

| Pancreas-carcinoma | 57 (32.8) |

| Cholangio-carcinoma | 33 (19.0) |

| Gastric-carcinoma | 31 (17.8) |

| Metastatic colorectal-carcinoma | 16 (9.2) |

| Papillary-carcinoma | 7 (4.0) |

| Gallbladder-carcinoma | 5 (2.9) |

| Other carcinoma (local or metastatic) | 25 (14.3) |

| Benignancy | 70 (28.6) |

| Entities of benignancy | |

| Cholelithiasis | 32 (45.7) |

| Postoperative biliodigestive anastomotic stricture | 22 (31.4) |

| Acute and chronic pancreatitis | 5 (7.1) |

| Sclerosing cholangitis | 4 (5.7) |

| Postoperative biliary leakage | 3 (4.3) |

| Anastomotic stricture and choledocholithiasis | 3 (4.3) |

| Juxtapapillary diverticulum | 1 (1.4) |

| Postoperative changes of bowel anatomy (%) | |

| Patients with an altered postoperative bowel anatomy | 124 (50.8) |

| Billroth operation II | 36 (29.0) |

| Gastrectomy | 28 (22.6) |

| Biliodigestive anastomosis | 20 (16.1) |

| Whipple and Traverso-Longmire operation | 14 (11.3) |

| Gastroenteric anastomosis | 11 (8.9) |

| Others | 15 (12.1) |

Evaluating the different types of interventions, in 96.4% of all the procedures, a biliary drainage was implanted. Specifically, internal biliary drainage was implanted in 51.0% of the patients (27.7% plastic endoprothesis and 23.3% self-expandable metal stent), external drainage was implanted in 44.3% of the patients and combined internal-external drainage was implanted in 2.7% of the patients. Furthermore, although performed less frequently, dilatation therapies were performed (17.7%), followed by papillotomies (13.7%) and extractions of biliary tract stones (8.7%; Table 2).

| Variables | Interventions (n = 755) |

|---|---|

| Types of intervention (in % per examination) | |

| Drainage | 533 (96.4) |

| Internal biliary drainage | 282 (51.0) |

| Plastic endoprosthesis | 153 (27.7) |

| Self-expandable metal stent (SEMS) | 129 (23.3) |

| External biliary drainage | 236 (44.3) |

| Combined internal-external drainage | 15 (2.7) |

| Dilation therapy | 98 (17.7) |

| Anastomotic stricture | 46 (8.3) |

| Biliary tract stricture | 36 (6.5) |

| Metal stent stricture | 9 (1.6) |

| Papilla | 7 (1.3) |

| Papillotomy | 76 (13.7) |

| Extraction of biliary tract stones | 48 (8.7) |

Technical success and adverse events of percutaneous approaches

In 481 of the 553 examinations, the percutaneous procedures were successfully performed, resulting in a high overall technical success rate of 87.0% (Table 3). PTCs had a significantly higher technical success rate (89.7%) than PTE-RVs; however, the technical success rate of PTE-RVs was high, too (80.4%; Table 3; p < 0.003).

| Variables | Overall | PTE-RV | PTC | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical success (%) | 481/553 (87.0) | 131/163 (80.4) | 350/390 (89.7) | p < 0.003a |

| Technical failure (%) | 72/553 (13.0) | 32/163 (19.6) | 40/390 (10.3) |

- Two-sided p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

No adverse events occurred following most procedures (76.5%); however, in 23.5% of patients, adverse events were observed as follows (Table 4): In 12.8% of all patients, procedure-related complications occurred, while drainage-related complications occurred in another 10.7% of patients. The most frequent procedure-related complications included inflammatory complications like acute pancreatitis, acute cholangitis and peritonitis (4.2%), followed by major bleeding (3.6%; e.g. liver hematoma, biliary tract bleeding and other bleeding), pulmonary complications (2.4%), anesthesia-related complications (1.5%) and liver biloma (0.5%) (Table 4). Drainage-related complications occurred in 10.7% of all cases, and it occurred most frequently during the first week following the intervention (74.8% of all observed drainage-related complications). Only 25.2% of all cases developed drainage-related complications after the first week of the intervention (Table 4).

| Variables | Overall (n = 553) | PTE-RVs (n = 163) | PTCs (n = 390) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall complication rate | 130 (23.5) | 27 (16.6) | 103 (26.4) | 0.037a |

| Procedure-related complications (% per procedure) | 71 (12.8) | 14 (8.6) | 57 (14.6) | 0.069 |

| Systemic inflammatory reaction | 23 (4.2) | 5 (3.1) | 18 (4.6) | |

| Major bleeding | 20 (3.6) | 4 (2.5) | 16 (4.1) | |

| Pulmonary complications | 13 (2.4) | 2 (1.2) | 11 (2.8) | |

| Anesthesia-related complication | 8 (1.5) | 2 (1.2) | 6 (1.5) | |

| Liver biloma | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.8) | |

| Others | 4 (0.7) | 1 (0.6) | 3 (0.8) | |

| Drainage-related complications (% per procedure) | 59 (10.7) | 13 (8.0) | 46 (11.8) | 0.227 |

| Within one week | 44 (8.0) | 11 (6.7) | 33 (8.5) | |

| > 1 week and ≤ 1 month | 15 (2.7) | 2 (1.2) | 13 (3.3) |

- Two-sided p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The complications rates following PTC were compared to those following PTE-RVs as follows: The overall complication rate of PTE-RVs was 16.6%, while complications occurred in 26.4% of all the PTCs. Altogether, the overall adverse event rate following PTE-RVs was significantly lower than that following PTCs (p = 0.037). Consistently, procedure-related complications occurred less frequently following PTE-RVs (8.6%) than following PTCs (14.6%; Table 4).

Discussion

Based on this study, PTE-RVs, which have a technical success rate of 80.4%, are highly efficient for the treatment of bile duct obstruction in patients with failed ERC approaches. Furthermore, the complication rate following PTE-RVs was significantly lower than that following PTC alone (16.6% to 26.4%; p < 0.037).

In up to 92% of patients with a bile duct obstruction, biliary drainage can be facilitated using only endoscopic therapy.1,5,16,17 ERC offers all the advantages of endoscopic therapy, and general complications following ERC have been reported in approximately 7% of cases.18 Nevertheless, in certain cases, biliary drainage is challenging because of altered gastrointestinal or biliary anatomy, which is why percutaneous approaches such as PTCs and PTE-RVs remain rescue approaches.1-4 Additionally, percutaneous procedures might also be valuable for the treatment of iatrogenic lesions that do not allow an endoscopic approach,19 although this was not the case in our study cohort.

Many patients undergoing percutaneous procedures suffer from increased morbidity,20,21 which is confirmed in our study cohort in which more than 70% of patients had a diagnosis of malignancy. Especially these patients require repeated biliary interventions during their course of disease, which is documented by the fact that in our cohort approximately two procedures per patient were performed during the study period.

Although RV procedures have been known for more than 20 years, most studies report only small numbers of procedures, and only two studies included more than 50 examinations (Table 5).7,8,10-13,21-27 Compared to previously published studies, our study cohort represents the largest available data set of PTE-RVs (n = 163; Table 1, Table 5).

| First author, yearref | Study design | No of examinations included (n) | Technical success rate (%) | Complication rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tsang, 19877 | Retrospective cohort | 11 | 100 | 27.3 |

| Robertson, 19878 | Retrospective cohort | 14 | 85.7 | 0% early complications 21.4% mortality within 30 days |

| Ponchon, 198710 | Retrospective cohort | 19 | N/A | 10.5 |

| Dowsett, 198911 | Retrospective cohort | 74 | 81.1 | 12.5 |

| Verstandig, 199322 | Retrospective cohort | 44 | 97.6 | 22.7 |

| Hunt, 199323 | Retrospective cohort | 35 | 100 | 23 |

| Freeman, 199613 | Prospective cohort | 31 | N/A | 22.6 |

| Calvo, 200112 | Retrospective cohort | 13 | 93 | 7 |

| Wayman, 200324 | N/A | 41 | 95.1 | 48.8 |

| Neal, 201025 | Retrospective cohort | 106 | 92.5 | 24.5 (in-hospital morbidity) |

| Chang, 201026 | Retrospective cohort | 20 | 100 | 10 |

| Tomizawa, 201421 | Retrospective cohort | 26 | 88 | 19.2 |

| Yang, 201727 | Retrospective cohort | 42 | 92.9 | 7.1 |

- N/A: not available.

One study aim was to analyze the technical success rate of RV procedures. Regarding PTC, the general technical success rates of the establishment of percutaneous access to the biliary tract range from 88% to 98%.3,28,29 In our study, we successfully established percutaneous access to the biliary tract allowing a subsequent intervention in 89.7% of the cases, which is comparable to previous studies and was significantly superior over PTE-RVs (p < 0.003). For technical reasons, PTE-RVs have lower technical success rates than do PTCs because in addition to establishing percutaneous access, endoscopic access is required. Previous studies have reported technical success rates ranging from 81.1% to 100% (Table 5)7,8,10-13,21-27; these rates are comparable to that in our study, in which the technical success rate was 80.4%. In conclusion, although PTCs have higher technical success rates, PTE-RVs can successfully be performed in many patients.

Our aim was to analyze the safety of PTE-RVs compared with that of PTCs because of the lack of reliable data (Table 5).7,8,10-13,21-27 Following PTCs, the complication rates range from 9% to 26%.28,30,31 Furthermore, we included both procedure-associated and drainage-associated complications occurring within the first 30 days of the intervention, which was also performed by Li et al. (26% complications).30 Similarly, we report a PTC complication rate of 26% (procedure-related complications 14.6% and drainage-related complications 11.8%). As stated previously, the complication rates of PTE-RVs are not well known, and previous studies report complication rates with a wide range from 0% to 48.8% (Table 5).7,8,10-13,21-27 Regarding PTE-RVs, we performed a comprehensive data analysis of complications, including all procedure-related complications and drainage-related complications occurring up to 30 days after the intervention. Following PTE-RVs, we observed an overall complication rate of 16.6%, which can be subdivided into a procedure-related complication rate of 8.6% and a drainage-related complication rate of 8%. In contrast to previous studies, we compared the safety of PTE-RVs and PTCs and observed a significantly lower complication rate following PTE-RVs (16.6% vs 26.4%; p < 0.037). The lower procedure-related complication rate following PTE-RVs could be explained by the fact that the devices, for example, stent placement or stone extraction accessories, can be inserted via the endoscopic rather than the transhepatic route. Furthermore, data concerning the time of the occurrence of drainage-related complications are lacking. In our detailed analysis of the study cohort, most drainage-related complications occurred during the first week of the intervention (74.8%), which should remind clinicians to closely monitor these patients during the first days after the intervention. In summary, we used the largest available data set of RV procedures, and compared to PTCs, we observed significantly fewer complications following the RV procedures. Thus, if RV procedures are technically feasible, they may be more favorable than PTCs in terms of safety.

Our study has several limitations. First, we reported data from a retrospective analysis; nevertheless, all previous studies were retrospective, and we were able to collect a large, comprehensive and complete data set featuring detailed endoscopic reports. Second, we presented results from a single-center study; however, we reported the largest available data set of PTE-RVs available to date. Third, complication rates might vary across studies because of differently applied complication criteria: For example, fever is a necessary requirement for the diagnosis of cholangitis; however, fever might be defined using different body temperature cutoff values.32,33 To face this concern, we provided a detailed section on the definition of complications according to the recent guideline and the endoscopy lexicon of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; these guidelines focus on complications related to endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography and not to percutaneous procedures.34,35 Fourth, although PTE-RVs are rescue approaches, ultrasound-guided rendezvous procedures (EUS-RVs) have recently gained popularity; however, PTE-RVs have several unique clinical indications compared with EUS-RVs; for example, PTE-RVs can be performed in patients with surgically altered enteric anatomy (applicable to 50% of our included patients), in patients with a tight hilar biliary stricture through which only a guidewire but not a stent assembly can be passed, in patients in whom a guidewire insertion into the right intrahepatic duct has failed because EUS-RV typically requires access to the left intrahepatic duct via the transgastric route, and in patients with a preexistent percutaneous biliary drainage that can be easily used as an anterograde route for PTE-RVs.27

In conclusion, PTE-RVs provide high technical success rates (80%). In case of a necessary percutaneous procedure, RV techniques may be more favorable than PTC in terms of safety, and they provide all the advantages of endoscopic therapy.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions include the following: A.B. and F.L. designed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. F.M., H.N., M.B., D.B., T.N., T.B. and H.U. analyzed the data and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All the authors edited the scientific content of the manuscript and approved the final version prior to submission. For access to the underlying study materials, contact the corresponding author.

Declaration of conflicting interests

None declared.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Medical Council of Westphalia-Lippe and the ethics board of the Westphalian Wilhelms-University of Münster, Germany (date of approval: December 21, 2017). This study conforms to the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in the prior approval by the institution's human research committee.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Informed consent

As approved by the ethics board, informed patient consent was not required for this study because of its retrospective design.