Technical feasibility of EUS-guided antegrade dilation for hepaticojejunostomy anastomotic stricture using novel endoscopic device (with videos)

Abstract

Background

A novel endoscopic dilation device (EZ Dilator; Zeon Medical Co, Tokyo, Japan) is now available in Japan that might affect dilation for biliary strictures under endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) guidance because it has good push ability. We evaluated the technical feasibility of this device under EUS guidance in a case series of patients with hepaticojejunostomy anastomotic stricture (HJAS) that led to further complications.

Method

We enrolled 14 patients with HJAS leading to obstructive jaundice or repeated cholangitis in this study. Technical success was defined as insertion of the EZ Dilator into the intestine across the stricture site without the need for other dilation devices. Deployed plastic stents were removed after three months to evaluate anastomosis sites.

Results

The median procedural duration was 25 minutes. Rates of technical and clinical success were 100% and 78.5%, respectively. One patient developed an adverse event of abdominal pain. Contrast medium flowed across the anastomosis site in 11 patients after stent removal, indicating a clinical success rate of 78.5% (11 of 14). Plastic stents were deployed again in the remaining three patients.

Conclusion

Although a prospective evaluation with long-term follow up is needed, the EZ Dilator shows clinical promise for treating benign biliary strictures under ERCP and EUS guidance.

Introduction

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for patients with surgically anatomy such as the Roux-en-Y or Whipple procedure is sometimes challenging. Balloon enteroscopy allows access to the ampulla of Vater or biliopancreatoenteric anastomoses.1-4 However, the overall technical success rate in this setting varies from 66% to 100%.5 Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided biliary access was recently developed as an alternative to balloon enteroscopy,6-8 and the technical success rate of this approach might be high in expert hands. However, several procedures including stone removal and dilation for biliary strictures can be challenging because of the limited availability of devices. A novel endoscopic dilation device (EZ Dilator; Zeon Medical Co, Tokyo, Japan) has recently become available in Japan that might affect dilation for biliary stricture under ERCP and EUS guidance because it has a fine and powerful push ability. We evaluated the technical feasibility of this device under EUS guidance in a case series of patients complicated with hepaticojejunostomy anastomotic stricture (HJAS) after pancreatoduodenostomy.

Patients

This pilot study proceeded at Osaka Medical College between December 2016 and March 2018 and was approved by the institutional review board of our hospital. The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in the a priori approval given by the human research committee at the institution.

Written, informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from 14 consecutive patients (median age 68 years; male, n = 10) who were complicated with obstructive jaundice or repeated cholangitis due to HJAS.

Technical tips for EUS-guided antegrade dilation (videos)

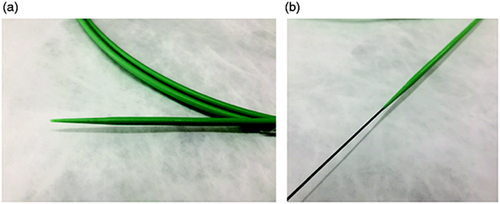

The novel EZ Dilator endoscopic dilation device was evaluated in the present study (Figure 1(a) and (b)). The maximum diameter at the tip of this device is 2.33 mm, which is extremely fine. The device offers good push ability and a smaller difference in diameter compared with the 0.025-inch guidewire.

The EZ Dilator (Zeon Medical Co, Tokyo, Japan). (a) The tip of this device is extremely fine, with a maximum diameter of 7 Fr. (b) The device is characterized by good push ability and a smaller difference in diameter compared with a 0.025-inch guidewire.

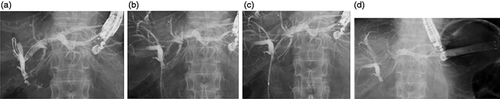

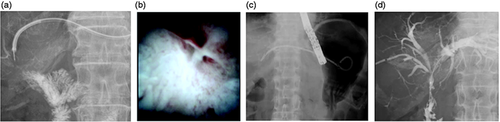

An echoendoscope (UCT 260, Olympus Optical Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) connected to an ultrasound device (SSD5500; Aloka Medical Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), was advanced into the stomach, and the intrahepatic bile was visualized. We then punctured the intrahepatic bile duct using a 19 G needle for fine-needle aspiration (FNA) (SonoTip Pro Control; Medi-Globe GmbH, Rohrdorf, Germany). Bile juice was aspirated, contrast medium was injected for cholangiography, then a 0.025-inch guidewire (VisiGlide 1; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted into the intrahepatic bile duct through the FNA needle. An ERCP catheter (MTW Endoskopie Co, Düsseldorf, Germany) was inserted, and contrast medium was injected again (Figure 2(a)). The guidewire was advanced into the intestine across the stricture site (Figure 2(b)), then the EZ Dilator was inserted immediately without the need for any other dilation devices (Figure 2(c)). Finally, a Niti-S Biliary covered metal stent (TaeWoong Medical, Seoul, South Korea) was deployed from the intrahepatic bile duct to the stomach (Figure 2(d), online supplemental Video 1). This stent was removed after 10 days, the stricture site was evaluated, and a forceps biopsy proceeded using per oral transluminal cholangioscopy as described (Figure 3(a), (b)).9 A plastic Type IT stent (Gadelius Medical Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) was alternatively placed to maintain the fistula in position between the liver and the stomach (Figure 3(c)). Patients were excluded from the study at this point if malignancy was diagnosed based on visual and histological findings (online supplemental Video 2).

(a) A tight stricture is located at the hepaticojejunostomy anastomotic site, and the endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography catheter cannot advance into the intestine. (b) The guidewire is advanced into the intestine. (c) The EZ dilator can be inserted into the intestine across the stricture site. (d) A covered metal stent is deployed from the intrahepatic bile duct to the stomach.

(a) The metal stent is removed, and a cholangioscope is inserted into the biliary tract through the fistula. (b) The tumor is not evident at the hepaticojejunostomy site. (c) A plastic stent is deployed. (d) The hepaticojejunostomy stricture is resolved three months later.

The plastic stent was removed three months later. An ERCP catheter was inserted into the biliary tract through the fistula, and contrast medium was injected. If the contrast medium flowed into the intestine across the anastomotic site, a plastic stent was not deployed (Figure 3(d)). If the contrast medium did not flow into the intestine, the same type of plastic stent was deployed from the intrahepatic bile duct to the stomach.

Definitions and statistical analysis

We defined technical success as insertion of the dilation device into the intestine across a stricture site without the need for other dilation devices. Clinical success was also evaluated when the plastic stent was removed after three months. Clinical success was defined as contrast medium flowing into the intestine across the anastomosis site without HJAS. The procedural duration was determined from the time of echoendoscope insertion until stent placement. The severity of adverse events was graded according to the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy lexicon.10

Results

Table 1 shows that the patients underwent pancreatoduodenostomy because of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (n = 12), bile duct cancer (n = 1) and carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater (n = 1). HJAS occurred at a median of 18 (range 12–33) months after pancreatoduodenostomy. The patients underwent biliary drainage because of obstructive jaundice (n = 6) and cholangitis (n = 8). The median procedural duration was 25 minutes. Technical success was achieved in all patients, and one patient developed an adverse event of abdominal pain. After stent removal, contrast medium flowed across the anastomosis site in 11 patients, indicating a clinical success rate of 78.5% (11/14). Three patients underwent plastic stent placement. Finally, complications of recurrence of cancer were not seen in any patients.

| Total number of patients | 14 |

| Median age (years, range) | 68 (57 to 81) |

| Gender (male:female) | 10:4 |

| Reasons for pancreatoduodenostomy (n) | |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm | 12 |

| Bile duct cancer | 1 |

| Carcinoma of ampulla of Vater | 1 |

| Reasons for undergoing biliary drainage | |

| Obstructive jaundice | 6 |

| Cholangitis | 8 |

| Median procedure time (minutes, range) | 25 (20 to 32) |

| Technical success (%, n) | 100 (14/14) |

| Clinical success (%, n) | 78.5 (11/14) |

| Adverse event (%, n) | 7 (1/14) |

Discussion

Although HJAS is a rare complication of pancreatoduodenostomy, occurring in 3% to 7% of patients within 2.3 to 4.1 years after this procedure,11 the prevalence might have increased because of recent improvements in early diagnosis of pancreatobiliary cancer and expanded operative indications including intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms.3 Endoscopy using an enteroscope or a percutaneous approach is the standard method for treating HJAS. Improved enteroscopes such as short double-balloon types have recently become available.2,12 Shimatani et al. evaluated this type of scope in patients with altered gastrointestinal anatomy such as Roux-en Y total gastrectomy (n = 36), Billroth II gastrectomy (n = 17) and pancreatoduodenostomy (n = 15).2 The endoscope was deeply inserted during 100 (97%) of 103 procedures in that study. In addition, cholangiography was achieved in 98 (98%) of 100 procedures, and therapeutic interventions such as stone removal, nasobiliary drainage, or stent placement proceeded without incident. On the other hand, Mizukawa and colleagues retrospectively analyzed the application of this scope in 46 patients with HJAS.12 The technical and clinical success rates were both 100% and the median procedural duration was 54 minutes. According to these reports, the enteroscopic approach might confer clinical benefits. However, one disadvantage of this procedure is that it is lengthy, which might lead to an increase in adverse events such as air embolism or aspiration pneumonitis.

EUS-guided biliary drainage was developed as an alternative method for patients who have advanced malignant tumors.1-4 In addition, the indications for EUS-guided biliary drainage have recently expanded to include benign diseases such as bile duct stones. Although this procedure has clinical benefits such as a high technical success rate, several procedures remain challenging because of limited types of endoscopic devices. Therefore, treatment for HJAS under an EUS-guided approach might be difficult. The EZ Dilator offers several benefits. It is relatively soft, and thus easy to advance into the intestine through the complex biliary tree. The device can dilate not only the HJAS but also the intrahepatic bile duct and the stomach wall. Therefore, EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy can be performed without any dilation device. This might help to decrease the prevalence of bile peritonitis or reduce the procedural duration, which in fact was only 25 minutes in the present study. Furthermore, none of our patients developed bile peritonitis.

Our technique is complex because several steps are required. As a result, the number of hospital admissions and the length of hospitalization might increase compared with the enteroscopic approach. However, if reintervention is required such as for HJAS stricture, our technique might facilitate a shorter procedure compared with the enteroscopic approach because of easier biliary access.

This study is limited by a short follow-up period, a small case series and the retrospective design.

In conclusion, a prospective evaluation with long-term follow-up is needed to confirm the present findings.

Declaration of conflicting interests

None declared.

Ethics approval

The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in the a priori approval given by the human research committee at our institution.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Informed consent

Written, informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from 14 consecutive patients (median age 68 years; male, n = 10) who were complicated with obstructive jaundice or repeated cholangitis due to HJAS.