Anxious Attachment Style Predicts Pathological Internet Use in Nursing Students: The Mediating Role of Alexithymia

Abstract

Aim: The study was aimed at determining the mediating role of alexithymia in the relationship between anxious attachment style and internet addiction in nursing students.

Method: The current cross-sectional study was conducted with nursing students studying in a province located in western Türkiye. The study data were collected from 266 students using the face-to-face interview technique with the self-report scales between February 2024 and June 2024. The descriptive statistics and correlation analyses of the current study were performed using the SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) 25.0 program, and the mediating role analysis was conducted using the PROCESS Macro model 4 for SPSS. The data obtained were analyzed with descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and mediating role analysis.

Results: The mean age of the participants was 21.18 (Min: 18, Max: 28). Of them, 165 (62%) were men, 101 (38%) were women, and only 3 (1%) were married. The time they spent for daily internet use varied between 1 and 5 h. Anxious attachment style predicts pathological internet use and alexithymia. At the same time, alexithymia predicts pathological internet use. Mediator role analyses indicate that alexithymia is a mediator in the relationship between anxious attachment and internet addiction (p < 0.05).

Conclusion: Nursing students, who will perform nursing, which has a crucial position in health services, should be provided with trainings on attachment styles, correct internet use, recognizing, and expressing emotions, and students at risk should be recognized and provided with professional psychosocial support if necessary. Testing the study hypotheses on nursing students in different regions would be beneficial for generalizing the findings. Considering the role of different attachment styles, it would be useful to investigate other variables that may mediate the relationship between attachment styles and pathological internet use.

1. Introduction

Pathological internet use (PIU), also defined as problematic internet use or internet addiction in different sources, refers to the excessive and uncontrolled use of the internet [1–3]. Individuals with PIU often struggle to manage their internet usage, using it as an escape from real-life problems like stress, anxiety, or loneliness [1, 2]. This behavior can result in social isolation and a decline in the quality of life, affecting performance at work or school and straining family relationships [4–6].

Davis [1] describes PIU using a cognitive–behavioral model, emphasizing maladaptive thoughts rather than just behavioral factors like withdrawal and tolerance. Specific PIU is often related to pre-existing psychopathology; for instance, a gambler might resort to internet gambling. Social isolation and lack of support might contribute to meaningless excessive internet use, characterized by procrastination and evasion of responsibilities. Symptoms include obsessive thoughts about the internet, reduced impulse control, and feelings of guilt, leading to further social withdrawal and dependency [1].

Previous research has shown an association between attachment styles and PIU [7–9]. Attachment refers to the connection that develops between a baby and their primary caregiver [10]. Shaped by Bowlby’s and Ainsworth’s work [11], attachment theory explains that secure attachment develops when a caregiver meets an infant’s needs, while unmet needs result in insecure attachment [12]. These styles influence cognitive schemas, behavior, and emotions in adulthood [13]. Attachment formed in infancy shapes adult relationships [14]. Bartholomew and Horowitz [15] identified three insecure attachment types in adults: anxious, avoidant, and preoccupied. These styles, although enduring, are likely to change through life events or interventions [16–18]. Although individuals’ attachment styles and their perceptions of self and others tend to persist from childhood into adulthood, they have the potential to change through life experiences, new relationship forms, or specific interventions [16–18].

Attachment styles significantly influence the formation of cognitive schemas pertaining to self-perception and interpersonal relationships [15, 19]. Consequently, insecure attachment styles may be linked to a range of pathologies in diverse manners. Existing research indicates that these insecure attachment styles are predictive of PIU [9, 20, 21]. However, given the categorical nature of attachment styles, it is anticipated that this relationship may present itself in various manifestations. Among these, anxious attachment—one of the insecure attachment styles—has substantial theoretical support for its role in predicting PIU.

The anxious attachment style emerges from insufficient and inconsistent experiences related to the provision of care in early childhood [13]. Individuals with this type of attachment style often exhibit marked dependency on others and a relentless need for reassurance, very frequently accompanied by feelings of inadequacy and a heightened fear of abandonment [22]. Moreover, it affects their strategy of dealing with stress negatively, hence making them more anxious and emotionally distressed [23].

There is evidence that anxious attachment styles are linked to PIU [24]. This connection is related to how people think about themselves and others. People with anxious attachment styles often fear rejection in relationships because they feel inadequate and worthless [25, 26]. Even though they want social interaction, these fears make it hard for them to engage in face-to-face encounters, so they turn to the internet. The internet feels safer and more secure than real-life interactions. However, relying on online communication can weaken their real social connections. Spending too much time online can reduce their social skills and lead to internet addiction. This can create a harmful cycle where social isolation increases internet use [27].

People with anxious attachment styles often have unrealistic views of relationships and struggle with negative self-image, which can heighten their anxiety [28]. They might turn to the internet as a way to manage negative feelings and anxiety, finding temporary relief and a sense of security through online interactions [29, 30]. However, this can lead to excessive internet use. Additionally, alexithymia complicates matters by making it hard for individuals to recognize and articulate their emotions, which can hinder their ability to use the internet as a healthy coping mechanism. This dynamic may worsen their reliance on online interactions, detracting from the development of more effective coping strategies.

Alexithymia is an emotional-cognitive disorder marked by a diminished awareness of emotions, particularly in recognizing and expressing them [31, 32]. People with alexithymia frequently experience their feelings through physical symptoms, which suggests a limited capacity to reflect on and manage their emotions [33]. The ability to identify emotions is a social learning skill that develops in early childhood, influenced by parental gestures, facial expressions, and verbal communication [34]. According to the multiple code theory, children internalize their parents’ emotional responses, which is crucial for their emotional development [35, 36]. Inconsistent and unresponsive caregiving can result in anxious attachment and a lack of emotional information [23]. As a result, the connection between anxious attachment and the ability to identify emotions is closely tied to stable caregiver relationships. Anxious attachment tends to correlate with higher levels of alexithymia [37]. This attachment style creates a persistent need for emotional validation, while alexithymia makes it difficult to recognize and express these needs, leading to challenges in relationships and emotional well-being [38].

The hyperarousal model of alexithymia suggests that alexithymia is linked to increased sympathetic arousal when faced with emotional stimuli [39]. Individuals with anxious attachment, who often experience significant anxiety in their relationships, may perceive threats related to alexithymia. High levels of alexithymia can provoke cognitive responses that are particularly relevant to insecure attachment styles [40]. Those with anxious attachment typically struggle with self-confidence in managing their emotions, making them more attuned to emotional threats [41]. To cope with these threats, they often seek more intimacy [42] and might resort to online spaces to address their insecurities, which can lead to internet addiction [27, 43].

People with alexithymia might turn to the internet as a way to avoid expressing their emotions. Engaging in online activities, such as video games, can provide a means to regulate and escape from feelings [44], but this behavior may negatively impact their offline social interactions and heighten the risk of internet addiction [45]. Both anxious attachment and alexithymia are linked to problematic internet use [43, 46].

Research indicates a connection between insecure attachment styles and alexithymia, which may predict problematic internet use [47, 48]. It is essential to explore these findings within the context of nursing students, who encounter various challenges in their clinical practice and education. Those with anxious attachment may constantly seek reassurance, which can impede their independence and decision-making abilities [49]. This attachment style may also influence their capacity to establish secure relationships with patients [50, 51].

For nurses, alexithymia can obstruct their ability to manage emotional health and respond effectively to patients’ needs, thereby impacting their coping strategies in high-stress situations [52]. The alexithymia–stress hypothesis posits that elevated levels of alexithymia can diminish stress resilience [53, 54]. The demands of nursing roles and the associated working conditions introduce a variety of stressors [55, 56]. There is evidence of relationships among alexithymia, stress, and burnout among nurses [57, 58]. Additionally, a lack of awareness regarding internet addiction among nurses may impede effective service delivery [59]. Engaging in risky internet use can adversely affect communication and decision-making, potentially leading to procrastination [60–62], which poses a risk to healthcare services [63]. It is vital to understand the factors that predict the problematic internet use among nursing students and to discuss interventions for those at risk.

To date, no studies have examined the relationships among attachment styles, PIU, and alexithymia in nurses and nursing students. Attachment styles are significant variables that determine thought patterns, emotional responses, and behaviors, as well as interpret personal differences. In this context, the current study aims to determine the mediating role of alexithymia in the relationship between anxious attachment style and PIU among nursing students. As explained in the introduction, the theoretical foundations of anxious attachment and its potential relationships with other variables will be investigated through the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1. There is a significant relationship between anxious attachment styles and pathological internet use among nursing students.

Hypothesis 2. Alexithymia mediates the relationship between anxious attachment styles and pathological internet use.

2. Participants and Procedure

The target population of this study involves the nursing students who study at the university located in one province of western Türkiye. Based on a G-Power analysis using the same scales as the study, a minimum sample size of 115 was calculated, considering a margin of error of 0.05 and a 95% confidence interval. A total of 266 students who provided their consent have participated in this study. According to the post hoc power analysis, the test power was determined to be 99%. This means that the statistical test has a 99% probability of correctly detecting a true effect when it exists [64]. Data collection took place between February 2023 and May 2023. The inclusion criteria included students studying at the relevant university within the period of the study and who were able to speak and understand Turkish. Foreign students who could not speak and understand Turkish easily were not included in the study. Participating students were informed about the study and gave written and verbal consent that they were willing to participate prior to data collection. Data collection was done from willing participants through face-to-face interviews, and no kind of incentives were given to them.

2.1. Data Collection Tools

-

Participant information form: The form was developed by the researchers to obtain information about the participants’ age, gender, marital status, and internet usage time.

-

Online Cognition Scale (OCS): The OCS was constructed by Davis in 2002. It is a 36-item scale that measures PIU. The OCS has four subscales: loneliness/depression, decreased control over impulses, comfort in social situations, and diversion. The OCS can also be scored to yield a global measure of PIU. The scale utilizes a seven-point Likert-type format, with responses ranging from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 7 (“Strongly Agree”), to measure harmful internet use in these four domains. The total score for the OCS can range from 36 to 252, with higher scores indicating more harmful internet use related to thoughts about the internet.

-

High scores in the social comfort section mean that one prefers online friendships to real-life ones. Elevated scores in the loneliness and depression scales indicate a heightened susceptibility to feelings of loneliness and depression in the absence of internet access. High scores in the area of low impulse control signify that one has more difficulties controlling urges to use the internet, while, at the same time, high scores in the distraction area suggest that one is rather predisposed to using the internet to avoid responsibilities. The OCS was translated into Turkish by Keser Özcan and Buzlu [65], and they conducted studies to test its validity and reliability. They found an internal consistency coefficient of α = 0.91 for the OCS; in the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient was 0.95.

-

Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20): The scale developed by Bagby, Taylor, and Parker [66] initially consisted of 26 items, but today, it was shortened to a 20-question version (Toronto Alexithymia Scale-20 (TAS-20)). The validity and reliability study of the Turkish version of the TAS-20 were performed by Güleç et al. [67]. Responses given to the items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 5. While the minimum score that can be obtained from the scale is 20, the maximum score is 100. High scores indicate that the level of alexithymia is high [67]. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the TAS-20 was 0.77 in the present study.

-

Experiences in close relationships inventory-II (ECRI-II): The ECRI-II, developed by Fraley et al. [68]; is an extensively used tool to assess adult attachment styles. This scale measures the level of anxiety and avoidance of attachment in close relationships with romantic partners, family members, and friends. The ECRI-II contains 36 items rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale and is divided into two subdimensions: attachment anxiety (18 items) and attachment avoidance (18 items). Odd-numbered items measure anxiety, while even-numbered items measure avoidance.

The ECRI-II yields two independent total scores, both ranging from 18 to 126. Scores on each dimension were higher in their respective attachment anxiety or avoidance [69]. Selçuk et al. [69] have published the Turkish validity and reliability study of the ECRI-II and reported Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90 for the avoidance dimension and 0.86 for the anxiety dimension. The test–retest reliability was found to be 0.82 for the anxiety dimension and 0.81 for the avoidance dimension [69].

In this study, we looked at the anxiety part of the scale, which had Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.81. The ECRI-II measures both attachment anxiety and avoidance; the sub-scales can be used either in conjunction or alone. In this study, the subscale assessing anxious attachment was used in accordance with the hypotheses.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

The present study has used SPSS 25.0 software for conducting descriptive statistics and correlation analysis. Data analysis was commenced with basic statistical measures including mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum values. Correlation analyses were performed after that to establish how the variables relate to each other. The normality of the variables was checked at this point. For the assumption of normal distribution, kurtosis and skewness values were examined. The results indicated that the data followed a normal distribution [70].

Mediation analysis was performed using PROCESS Macro model 4, an add-on in SPSS. This model is appropriate for testing the mediating effects that come into play in the relationship between the independent and dependent variables. In the analysis, gender and age variables were controlled for so that the results would be more reliable and valid. Data analysis was performed based on the Bootstrap method, which involved 5000 samples. Bootstrap is helpful in obtaining a better estimate of the sampling distribution, which is important for calculating confidence intervals. A 95% confidence interval that does not include zero is considered to be statistically significant according to Hayes [71]. This indicates a strong association between the independent and dependent variables and confirms that a mediating effect is statistically significant.

2.3. Ethical Issues

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Before the commencement of this study, ethical approval (2024/39) was obtained from the Yalova University Ethics Committee, and permission from the Faculty of Health Sciences where the study was to take place was secured. The necessary consents indicating that participants volunteered to participate in this study were obtained from individuals after they had been enlightened on the study.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

Of the participants, 165 (62%) were female and 101 (38%) were male, with ages ranging from 18 to 28 years (mean: 21.18). Only three participants (1%) reported being married. The daily internet usage among participants varied from 1 to 5 h (mean: 2.09 h). The mean scores of the variables and the Pearson correlation coefficients between the variables are presented in Table 1. There were positive and statistically significant relationships between anxious attachment and alexithymia (r = 0.442, p < 0.01) and problematic internet use (r = 0.349, p < 0.01). There was also a positive and statistically significant relationship between alexithymia and problematic internet use (r = 0.366, p < 0.01). Additionally, the relationships between the subdimensions of the OCS, alexithymia, and anxious attachment have been examined. It was found that there are positive and significant relationships between anxious attachment and all subdimensions of the OCS, as well as between alexithymia and all subdimensions of the OCS (p < 0.01).

| M + SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. AA | 66.04 ± 16.28 | 1 | ||||||

| 2. TAS | 53.41 ± 10.01 | 0.442 ∗∗ | 1 | |||||

| 3. SC | 32.33 + 12.97 | 0.269 ∗∗ | 0.331 ∗∗ | 1 | ||||

| 4. LD | 17.51 + 7.61 | 0.357 ∗∗ | 0.288 ∗∗ | 0.741 ∗∗ | 1 | |||

| 5. Distraction | 25.15 + 9.32 | 0.302 ∗∗ | 0.313 ∗∗ | 0.606 ∗∗ | 0.672 ∗∗ | 1 | ||

| 6. DIC | 35.23 + 12.03 | 0.334 ∗∗ | 0.354 ∗∗ | 0.740 ∗∗ | 0.837 ∗∗ | 0.708 ∗∗ | 1 | |

| 7. OCS | 110.27 ± 37.43 | 0.349 ∗∗ | 0.366 ∗∗ | 0.891 ∗∗ | 0.896 ∗∗ | 0.826 ∗∗ | 0.927 ∗∗ | 1 |

- Note: DIC = diminished impulse control subscale, LD = loneliness/depression subscale, M = arithmetic mean, SC = social comfort subscale.

- Abbreviations: AA = anxious attachment, OCS = online cognition scale, SD = standard deviation, TAS = Toronto alexithymia scale.

- ∗p < 0.05.

- ∗∗p < 0.01.

3.2. Mediation Analysis

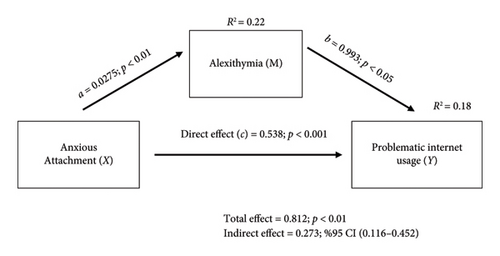

In Table 2 and Figure 1, direct and indirect effects between the variables are presented.

| TAS (M) | OCS (Y) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | LL | UL | β | SE | LL | UL | |

| AA (X) | 0.275 ∗∗ | 0.33 | 0.209 | 0.340 | 0.538 ∗∗ | 0.145 | 0.253 | 0.824 |

| TAS (M) | 0.993 ∗∗ | 0238 | 0.523 | 1.463 | ||||

| R2 = 0.22 | R2 = 0.18 | |||||||

- Abbreviations: AA = anxious attachment, LL = lower limit, OCS = online cognition scale, TAS = Toronto alexithymia scale, UL = upper limit.

- ∗p < 0.05.

- ∗∗p < 0.01.

In accordance with our hypotheses, a mediation analysis was conducted using the total score of the OCS. According to Table 2 and Figure 1, after checking for sex and age variables, anxious attachment predicted internet addiction (β = 0.538, 95% CI 0.253–0.824) and alexithymia significantly (β = 0.275, 95% CI 0.209–0.340), and alexithymia predicted internet addiction statistically significantly (β = 0.993, 95% CI 0.523–1.463). Anxious attachment accounted for 22% of the variance in alexithymia, and anxious attachment and alexithymia accounted for 18% of the variance in internet addiction.

In Table 3, direct and indirect effects of anxious attachment on internet addiction are presented. As seen in the table, the direct effect of anxious attachment on internet addiction was 0.353 and the total effect was 0.471. Anxious attachment predicts PIU mediated by alexithymia in a statistically significant way (β = 0.118, 95% CI 0.116–0.452). However, since anxious attachment directly predicted PIU in a statistically significant way, it is seen that alexithymia has a partial mediating role [72]. Approximately 33% of the total effect of anxious attachment on internet addiction was explained by alexithymia (0.273/0.812). This indicates that while anxious attachment directly influences internet addiction, a significant portion of this effect is mediated through alexithymia.

| Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | LL | UL | ||

| Direct effect | 0.538 ∗∗ | 0.145 | 0.253 | 0.824 | 0.353 |

| Indirect effect through TAS | 0.273 | 0.116 | 0.452 | 0.118 | |

| Total effect | 0.812 ∗∗ | 0.133 | 0.549 | 1.075 | 0.471 |

- Note: LL = bootstrap confidence interval lower limit, UL = bootstrap confidence interval upper limit.

- ∗p < 0.05.

- ∗∗p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

In the present study, it was determined that an anxious attachment style predicts PIU among nursing students and that alexithymia mediates this relationship. The hypotheses established within the scope of the study were confirmed. Simultaneously, the relationships between the subdimensions of the PIU measurement tool and other variables reveal significant findings.

The current study found that anxious attachment predicts PIU and that there are positive and significant relationships between anxious attachment and all subscales of the measurement tool evaluating PIU. Notably, there are positive and significant relationships between anxious attachment and the subscales of social comfort and loneliness/depression. This can be explained by the development of anxious attachment and the cognitions related to self and others in individuals with anxious attachment. Anxious attachment develops as a result of inconsistent and insensitive care from the primary caregiver [73]. During the process of anxious attachment, thoughts of inadequacy and worthlessness related to the self are prominent, and the fear of abandonment is intensely experienced [74, 75]. Individuals with an anxious attachment style, who experience a lack of self-confidence in interpersonal relationships, may prefer to form relationships in virtual environments. Previous evidence suggests that individuals with anxious attachment are more vulnerable to using social media, a form of internet use that facilitates relationships with others [76–78]. Various factors play a role in the development of an anxious attachment style, including trauma, emotional neglect, early separation from parents, and inconsistencies in parenting. Such experiences may lead individuals to develop a belief that their emotional needs will not be met [23]. Additionally, individuals with an anxious attachment style may be in constant search of approval and reassurance, which can lead them to spend more time in virtual environments.

Individuals with an anxious attachment style experience intense anxiety when they perceive uncertainty in their relationships and may use the internet as an escape or coping mechanism to reduce this anxiety [42, 79]. The internet can serve as a tool for these individuals to avoid emotional threats and meet their social needs. In this context, internet addiction and social media addiction may emerge as emotional regulation strategies for individuals with an anxious attachment style [80]. Previous evidence supports the findings of this study, showing relationships between anxious attachment and PIU [24, 81].

The current study also found significant and positive relationships between anxious attachment and the subscales of distraction and diminished impulse control. This is understood in light of views suggesting that the sense of acceptance and belonging enhances self-regulation skills [82–84]. People adjust their behaviors to be accepted and belong to a group [85]. If a person does not feel a sense of belonging or feels excluded, their ability to control themselves may decrease. The lack of a sense of belonging and the perception of rejection by others may impair the self-control skills of individuals with anxious attachment. Previous evidence indicates that individuals with anxious attachment are vulnerable to impulsive behaviors and addiction [86–89].

As expected, the current study found that anxious attachment predicts alexithymia. Parents who cannot provide secure, stable, and satisfying care play a role in the development of anxious attachment and deprive the child of emotional messages during early childhood [23]. Children who do not receive adequate emotional messages and cannot interact with their emotional responses due to parental inadequacy during development may develop alexithymia [37]. Trauma and emotional neglect experienced, particularly during early childhood, result in difficulties in feeling and identifying emotions later in life [90]. This situation may be more pronounced in individuals with an anxious attachment style, as they may develop a strong belief that their emotional needs will not be met. Previous evidence is consistent with the findings of the present study, showing a relationship between anxious attachment and alexithymia [37].

The present study found that alexithymia predicts PIU. Previous studies showing a positive relationship between alexithymia and internet addiction are consistent with the results of the present study [47, 91–94]. Individuals with alexithymia, who have difficulties in identifying, expressing, and communicating emotions, may better regulate their emotions in a virtual environment and use the internet as a tool for social interaction to meet their unmet social needs in daily social life [95]. Indeed, the present study found positive and significant relationships between alexithymia and the subscales of social comfort and loneliness/depression. The inability to regulate emotions through cognitive processes and the disturbances in emotional awareness can result in alexithymic individuals engaging in impulsive behaviors to cope with unpleasant emotional states [96, 97]. The present study also found a positive relationship between alexithymia and the diminished impulse control subscale.

As expected, the present study found that an anxious attachment style predicts PIU through alexithymia. The role of attachment styles in shaping cognitions about the self and others is well known. Individuals with an anxious attachment style have a pronounced sense of inadequacy about themselves and tend to seek approval from others in interpersonal relationships [15, 25]. Individuals with an anxious attachment style, who frequently experience feelings of abandonment and rejection in interpersonal relationships, experience intense anxiety when they perceive uncertainty in their relationships [42]. As indicated in the hyper-arousal model of alexithymia, the perception of emotional threats such as abandonment or disapproval and the perception of coping inadequacy can trigger alexithymia in individuals with an anxious attachment style [39]. However, increased sensitivity to emotional threats in individuals with high levels of alexithymia can activate cognitions specific to anxious attachment [40]. Consequently, the increased anxiety and need for relationships triggered by these reciprocal and complex relationships between anxious attachment and alexithymia are thought to be related to internet use behavior. Previous evidence supports that the internet can be used not only as a tool to cope with negative emotions but also to meet validation needs through online relationships [78, 98].

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

The results obtained indicate that anxious attachment in nursing students predicts internet addiction through alexithymia. Attachment theory has an important place in explaining normal or pathological behaviors. Attachment styles develop in early childhood and shape individuals’ cognitive schemas, emotions, and behaviors. That there are nurses with different attachment styles is an expected result. Considering the key role that nurses play in health services, it is important for nurses to be aware of their own attachment styles and to be knowledgeable about the relationship between attachment styles and behaviors. Nursing students’ being aware of their emotions and being able to express these emotions in order to prevent pathological behaviors in nursing students is of great importance. Within this context, it is recommended that nursing students should be given training on healthy internet use, alexithymia, and attachment styles, and that these trainings should be continued. Special interventions and trainings on these issues in education programs can positively affect students’ emotional health and professional performance. It is also recommended that nursing students at risk should be identified and, if necessary, they should be provided with psychosocial support.

5.1. Limitation

The present study has some limitations. The study data are applicable only to surveyed undergraduate nursing students in a province in the northwestern part of Türkiye. It is recommended that it would be useful to test the study hypotheses on nursing students in different regions. In the present study, the mediation role of alexithymia in the relationship between anxious attachment and internet addiction was investigated within the framework of attachment theory. The different attachment styles defined by the attachment theory differ from each other according to cognitions about self and others and the emotions and behaviors that emerge due to these cognitions. Within this context, different variables may affect the relationship between each attachment style and PIU. It is thought that it would be useful to consider different variables that may mediate the relationship between other attachment types and PIU in the future. Another limitation of the current study is that it is cross-sectional. It is thought that it would be useful to evaluate the relationships among anxious attachment, alexithymia, and problematic internet use in nursing students through longitudinal studies in future studies.

In the current study, PROCESS Macro was chosen for the mediation analysis based on the sample size and the established hypotheses. Although PROCESS Macro provides a convenient tool for conducting mediation and moderation analyses, it has some limitations compared to SEM. First, compared with the SEM, the analysis through PROCESS Macro is less complex; hence, it may sometimes fail to explore all the complex relationships and multiple mediation effects. Another condition is that PROCESS Macro works well with smaller groups; SEM requires larger groups for the model to be examined. In checking the level of fit of a model, PROCESS Macro provides limited information about the fit, while SEM has numerous tests to consider whether the model is accurate. However, it is acknowledged that both methods yield accurate results, allowing researchers to make their selections based on sample size and hypotheses [99]. Consequently, due to the limited information provided by the PROCESS MACRO model regarding model fit, it is suggested that the hypotheses of the current study be evaluated using SEM in future research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

Open access was supported by TÜBİTAK ULAKBİLİM.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.