Exploring the Relationships Between Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout, Secondary Traumatic Stress, and Resilience Among Nurses: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach

Abstract

Aim: This study investigates the connections between resilience, compassion satisfaction (CS), burnout (BO), and secondary traumatic stress (STS) among mental health nurses using structural equation modeling (SEM).

Design: A cross-sectional study.

Methods: Data were collected from 177 mental health nurses employed at a Mental Health Hospital in Saudi Arabia. Resilience, CS, BO, and STS were measured using the CD-RISC-25 and ProQOL scales. SmartPLS 3 software was employed for data analysis, including examining factor loadings, assessing composite reliability, and conducting SEM.

Results: The study findings indicate that resilience did not directly impact STS significantly (β = −0.03, t = 0.38, p = 0.704). However, resilience showed a significant positive influence on CS (β = 0.73, t = 16.41, p ≤ 0.001), while CS had a significant negative effect on BO (β = −0.35, t = 3.75, p ≤ 0.001). Moreover, BO demonstrated a significant positive impact on STS (β = 0.96, t = 20.04, p ≤ 0.001). Mediation analysis revealed that both CS and BO fully mediated the relationship between resilience and STS (β = −0.25, t = 3.41, p ≤ 0.001).

Conclusion: These findings emphasize the importance of developing resilience and promoting compassion to alleviate BO and reduce the risk of STS among mental health nurses. They highlight the need for implementing strategies that enhance resilience and support well-being in the workplace.

1. Introduction

Nursing is an inherently demanding and challenging profession, placing nurses at a high risk of experiencing significant stress and emotional strain [1]. Nurses often find themselves in high-pressure environments, working long hours, and dealing with complex patient care needs, resulting in emotional exhaustion, burnout (BO), and secondary traumatic stress (STS) [2, 3]. Specifically, mental health nurses are required to deal with and manage patient violence, which puts an extra burden on them as professional nurses besides their routine nursing care. For instance, a meta-analysis study among mental health nurses reported that BO was linked with job-related stress, overload, experience, and gender [4]. Adding to that, a study showed a high association between posttraumatic stress disorder related to work, STS, and BO among mental health nurses due to workplace violence [5]. BO and STS are recognized as major concerns within the nursing profession, contributing to various negative outcomes such as reduced job satisfaction, compromised quality of care, increased rates of absenteeism [6], and higher turnover rates [7, 8]. Research has indicated that mental health nurses experience elevated levels of STS and BO, along with diminished levels of compassion satisfaction (CS) compared to their counterparts in other nursing specialties [9].

Literature consistently highlights the significant prevalence of BO and STS among nurses, shedding light on the psychological toll of their demanding work environments. BO is a well-defined psychological response that arises from chronic work-related stress, characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment [10]. On the other hand, STS refers to the condition that can emerge in individuals indirectly exposed to traumatic events, such as nurses providing care to patients who have experienced trauma [11]. These conditions have profound implications for the well-being and overall functioning of nurses in their professional roles.

Resilience has emerged as an essential factor in promoting nurses’ well-being and preventing BO and STS [12]. Resilience refers to the ability to adapt to and recover from adversity, maintain psychological stability in the face of stress and change, and function effectively despite challenging circumstances [13, 14]. Research has shown that resilience is positively associated with CS, as well as positive health outcomes, increased job satisfaction [14, 15], and decreased BO and STS among healthcare professionals [16, 17].

Previous research has consistently demonstrated that resilience serves as a protective factor against BO and STS among nurses, indicating its importance in promoting their well-being [12]. Moreover, job satisfaction has been consistently linked to nurses’ overall well-being, with higher job satisfaction associated with better outcomes [18, 19]. Studies have shown a negative correlation between job satisfaction and BO [20, 21] and a positive correlation between job satisfaction and CS [18].

Although there has been increasing interest in exploring the interplay between resilience, CS, BO, and STS among nurses, there is still a notable gap in the literature regarding comprehensive examinations of these variables within a single model. Consequently, this study fills a crucial research void by employing a structural equation modeling (SEM) approach to investigate the intricate relationships among resilience, CS, BO, and STS among mental health nurses. The findings derived from this study have important implications for the development of interventions aimed at enhancing nurses’ well-being and promoting a healthier work environment.

Several studies examined the mediation effect between CS BO, STS, and resilience among nurses. For instance, among critical care nurses, resilience has been identified to play a mediating effect between BO and STS [22]. Additionally, among newly graduated nurses, CS was found to have a mediating effect between STS and posttraumatic growth [23]. Adding to that, among nurses working with terminally ill patients, job BO was found to be a mediator between STS and resilience [24]. Moreover, BO may mediate the relationship between job satisfaction and STS, further emphasizing the intricate interplay between these variables [25]. However, few empirical studies have integrated all four variables—CS, BO, STS, and resilience—into a single SEM framework, particularly within the context of mental health nursing, where nurses work in highly stressful environments. To address this gap, the present study contributes to the international literature by offering a comprehensive model that examines both the direct and mediating effects of resilience and CS on BO and STS.

In Saudi Arabia, a recent study examined the mediating role of social support in the relationship between BO and STS among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic [26]. However, research on the professional quality of life among nurses in general remains limited [27], and only one study has specifically focused on mental health nurses [28]. Notably, that study did not utilize SEM to explore the complex interrelationships among key variables. Therefore, this study offers novelty in its methodological approach, using advanced SEM analysis, and its focus on the underrepresented population of mental health nurses, with findings that hold potential relevance beyond the local context. Given the growing concern over nurse BO and trauma-related stress worldwide, this research offers implications not only for Saudi Arabia but also for broader international healthcare systems. High rates of BO and STS can jeopardize patient care, increase healthcare costs, and undermine workforce stability [29, 30]. Thus, promoting nurse resilience and CS could be a key strategy in building a more sustainable and effective healthcare workforce.

The conceptual model for this study is based on compassion fatigue theory and the stress-process theory. Compassion fatigue theory [31] explains that healthcare professionals, such as nurses, are at an increased risk of BO and STS due to prolonged exposure to patients’ suffering, while CS may serve as a protective factor. The stress-process theory [32] emphasizes how personal attributes, such as resilience, influence individuals’ responses to stress and help mitigate negative emotional outcomes. Guided by these theories, the present study hypothesizes that resilience has a positive impact on CS and indirectly reduces BO and STS. This is supported by recent research highlighting the role of self-compassion and resilience in promoting nurses’ psychological well-being, and it supports the development of a comprehensive model to understand the factors influencing nurses’ professional quality of life [33].

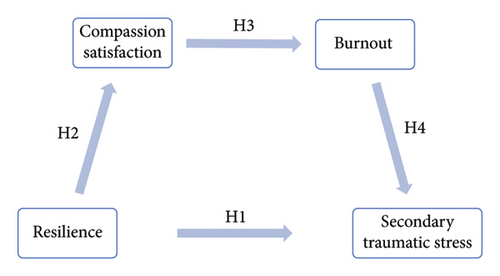

The conceptual framework of this study is grounded in two key theoretical models: compassion fatigue theory and stress-process theory. Compassion fatigue theory [31] posits that healthcare professionals, particularly nurses, are at a heightened risk of experiencing BO and STS due to continuous exposure to patients’ suffering. Within this framework, CS functions as a protective factor that may buffer against these negative outcomes. Meanwhile, the stress-process theory [32] underscores the role of personal resources, such as resilience, in shaping individuals’ responses to stress and mitigating its adverse emotional consequences. Informed by these theories, the conceptual model (Figure 1) was structured to reflect both direct and indirect influences among resilience, CS, BO, and STS. Specifically, the model proposes that resilience directly reduces STS and positively influences CS. In turn, CS is hypothesized to reduce BO, while BO is expected to increase STS. This pathway highlights both the mediating role of CS and BO and the interplay between protective and risk factors affecting nurses’ professional quality of life.

This theoretical integration provides a more comprehensive depiction of the interrelationships among the study variables and supports the development of a nuanced understanding of the psychological well-being of mental health nurses. Recent studies further support this model by demonstrating the critical role of resilience and self-compassion in improving nurses’ professional functioning and emotional resilience [33].

Therefore, this study aims to explore the relationships among resilience, CS, BO, and STS in mental health nurses. It also investigates the potential mediating role of CS in the relationship between resilience and both BO and STS. This study is significant as the mental health nurse nature of the job is required to deal with patients with different mental illness symptoms; for instance, psychosis, suicide, and violence, which in previous studies was a link with nurses’ BO and STS, which might affect mental health nurses’ work quality of their job and retention. Previous research has linked these stressors to higher levels of BO and STS, which can negatively impact job performance and staff retention. This study also seeks to examine the extent to which resilience and CS may serve as protective factors against BO and STS. By applying the SEM approach, the research aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between these variables. The findings will help inform strategies and interventions to support mental health nurses’ well-being, improve workforce retention, and enhance the overall quality of patient care. Given the demanding nature of mental health nursing, this study is both timely and highly relevant.

-

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Resilience will have a significant effect on secondary traumatic stress.

-

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Resilience will have a significant effect on compassion satisfaction.

-

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Compassion satisfaction will have a significant effect on BO.

-

Hypothesis 4 (H4): BO will have a significant effect on secondary traumatic stress.

2. Methods

2.1. Setting and Design

The collected data used a cross-sectional design from mental health nurses employed at the Riyadh Mental Health Center in Saudi Arabia. This government-operated facility provides comprehensive psychiatric, psychological, and social services to individuals with mental health disorders. The study specifically targeted eligible nurses who possessed a minimum of 3 months of experience and were directly engaged in the care of psychiatric patients within inpatient units, outpatient units, or psychiatric emergency rooms. The facility did not include other specialized units, such as medical intensive care units or nonpsychiatric departments. Exclusion criteria comprised nurses occupying leadership positions (e.g., supervisors) and those with limited clinical experience. These exclusions were implemented to cultivate a more homogeneous sample by concentrating on staff nurses who are more consistently and directly engaged in daily patient care, thereby ensuring similar exposure to mental healthcare challenges. The criteria were clearly articulated to ensure that potential participants could easily understand them and to maintain consistency and alignment with the study objectives. The data used in the present study were originally collected as part of a larger project titled “The relationship between psychological resilience and professional quality of life among mental health nurses” [28].

2.2. Sample Size and Technique

2.3. Instruments

The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-25) [35] is a tool used to assess resilience. It consists of 25 items that are scored on a five-point scale, ranging from 0 to 4. This scale measures participants’ resilience levels over the past month and provides a total score between 0 and 100. Higher scores indicate higher levels of resilience. The CD-RISC-25 has been validated in different contexts and versions, demonstrating reliability with Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.89 [35]. In our study, we used the Arabic version of the CD-RISC-25, which also exhibited Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.89 [36]. The internal consistency of this version was measured to be 92.8% using Cronbach’s alpha in the current study.

Developed by Stamm et al. [37], the Professional Quality of Life (ProQoL) tool is used to assess the positive and negative factors that impact the quality of professional life for helping professionals. It consists of a 30-item scale with three subscales: CS, BO, and STS. Respondents rate their experiences over the past 30 days on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 5, with reverse-coded items. CS, BO, and STS scores are calculated by summing specific items, each of which has reliability coefficients of 0.87, 0.72, and 0.81, respectively. The Arabic version of the scale demonstrated Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.84, 0.78, and 0.73 for CS, STS, and BO, correspondingly [38]. In our study, the reliability alphas for CS, BO, and STS were 88.3%, 72.1%, and 80.5%, respectively.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

The study obtained ethical approval from Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University (IRB-PGS-2022-04-148) and received prior authorization from the Mental Health Hospital. Participants were furnished with comprehensive information regarding the study’s objectives, potential benefits, risks, confidentiality measures, and the voluntary nature of their participation. Electronic informed consent was secured prior to participation, with consent confirmed by selecting the “I Agree” button on the online survey platform (QuestionPro). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any point without incurring any penalties.

2.5. Data Analysis

For data analysis, the study utilized SmartPLS 3 software. The software was employed to assess various factors, such as factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE), ensuring the convergent validity of the study. Prior to conducting the SEM analysis, preliminary assessments were conducted to ensure normality and evaluate assumptions related to multicollinearity. The SEM analysis itself was carried out using SmartPLS 3.0 software, allowing the researchers to test the hypothesized model and explore the relationships between the latent constructs, including both direct and indirect effects. To assess the significance of the relationships in the model, the researchers employed the bootstrapping technique, generating confidence intervals and conducting a minimum of 5000 bootstrap resamples. A significance level of p < 0.05 was set for the analysis. The results obtained from the SEM analysis were then used to evaluate the hypothesized model and investigate the mediating role of CS and BO in the relationship between resilience and STS.

Data were analyzed utilizing SmartPLS version 3.2.9. The analysis adhered to the methodologies employed in our previous study [39], encompassing the evaluation of measurement model validity through factor loadings, AVE, and CR, as well as the assessment of structural model path coefficients via bootstrapping techniques.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

The gender distribution among 177 mental health nurses demonstrated a nearly equal split, with 50.3% being male and 49.7% being female, with an average age of 33.8 years. The majority of participants were married and held a Bachelor of Science in Nursing degree. Furthermore, nearly two-thirds of the nurses reported having children. On average, the participants had 11.3 years of nursing experience.

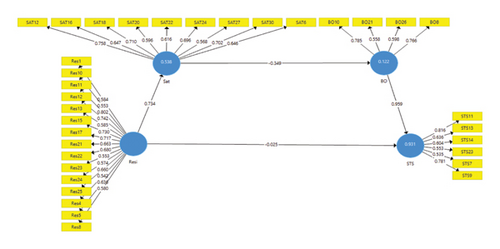

3.2. Measurement Model (Figure 2)

As part of the measurement model evaluation, 21 items (Res 2, Res 3, Res 6, Res 7, Res 9, Res 14, Res 16, Res 18, Res 19, Res 20, SAT 3, BO 1, BO 4, BO 15, BO 17, BO 19, BO 29, STS 2, STS 5, STS 25, STS 28) were excluded from the analysis due to low factor loadings and lack of significance with their respective scales. To assess construct reliability, Cronbach’s alpha and CR were employed. All CR values exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70 [40]. Additionally, Cronbach’s alpha for each construct surpassed the 0.70 threshold.

Convergent validity was evaluated using AVE, which ranged from 0.42 to 0.47. According to [41], if AVE is below 0.50 but CR is above 0.6, the convergent validity of the construct is still considered adequate. Factor loadings were presented below, and based on [42], factor loadings in the range of ±0.30 to ±0.40 are considered to meet the minimum level of interpretability of the structure. All factors exhibited high significance with their respective subscales. Furthermore, multicollinearity was evaluated through the application of the variance inflation factor (VIF), with observed values ranging from 1.28 to 2.87. These values are below the suggested threshold of 3.3, thereby indicating the absence of multicollinearity concerns among the indicators. The results for reliability and validity, along with the factor loadings for the items, are summarized in Table 1.

| Items | Loading | Cronbach’s alpha | Rho_A | Composite reliability | AVE | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BO10 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.47 | 1.76 |

| BO21 | 0.56 | 1.50 | ||||

| BO26 | 0.60 | 1.85 | ||||

| BO8 | 0.77 | 1.42 | ||||

| Res1 | 0.59 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.42 | 1.67 |

| Res10 | 0.55 | 1.77 | ||||

| Res11 | 0.80 | 2.41 | ||||

| Res12 | 0.74 | 1.94 | ||||

| Res13 | 0.58 | 1.63 | ||||

| Res15 | 0.73 | 2.02 | ||||

| Res17 | 0.72 | 2.03 | ||||

| Res21 | 0.66 | 2.02 | ||||

| Res22 | 0.68 | 1.78 | ||||

| Res23 | 0.55 | 1.98 | ||||

| Res24 | 0.57 | 2.77 | ||||

| Res25 | 0.66 | 2.07 | ||||

| Res4 | 0.54 | 1.90 | ||||

| Res5 | 0.64 | 2.06 | ||||

| Res8 | 0.58 | 1.86 | ||||

| SAT12 | 0.76 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.44 | 1.97 |

| SAT16 | 0.65 | 1.66 | ||||

| SAT18 | 0.71 | 2.35 | ||||

| SAT20 | 0.60 | 1.91 | ||||

| SAT22 | 0.62 | 1.53 | ||||

| SAT24 | 0.70 | 2.15 | ||||

| SAT27 | 0.57 | 1.70 | ||||

| SAT30 | 0.70 | 1.99 | ||||

| SAT6 | 0.65 | 1.43 | ||||

| STS11 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.44 | 1.59 |

| STS13 | 0.64 | 2.65 | ||||

| STS14 | 0.60 | 2.87 | ||||

| STS23 | 0.55 | 1.41 | ||||

| STS7 | 0.54 | 1.28 | ||||

| STS9 | 0.78 | 1.94 |

- Note: Res: resilience, CS: compassion satisfaction.

- Abbreviations: BO, burnout; STS, secondary traumatic stress; VIF, variance inflation factor.

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion. The table shows that the square root of the AVE for each construct was greater than the interconstruct correlation, as presented in Table 2. Furthermore, discriminant validity was also evaluated using the heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations [43]. The values obtained were below the threshold of 0.90, indicating that discriminant validity has been established. Please refer to Table 3 for the specific results.

| Burnout | Resilience | Secondary traumatic stress | Compassion satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burnout | 0.68 | |||

| Resilience | −0.21 | 0.65 | ||

| Secondary traumatic stress | 0.97 | −0.22 | 0.66 | |

| Compassion satisfaction | −0.35 | 0.73 | −0.31 | 0.66 |

- Note: Bold is square root of AVE.

| Burnout | Resilience | Secondary traumatic stress | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience | 0.21 | ||

| Secondary traumatic stress | 0.96 | 0.23 | |

| Compassion satisfaction | 0.35 | 0.73 | 0.31 |

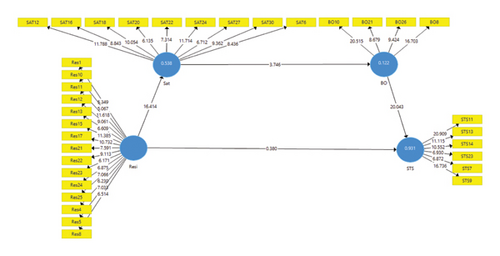

The structural model reflects the paths hypothesized in the research framework. A structural model is assessed based on the R2, Q2, and significance of paths. This study’s 5000 resamples also generate 95% confidence intervals as shown in Table 4. A confidence interval different from zero indicates a significant relationship. Hypotheses testing results are summarized in Table 4.

| β | SD | T statistics | pvalues | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Resilience -> secondary traumatic stress | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.38 | 0.704 |

| H2 | Resilience -> compassion satisfaction | 0.73 | 0.05 | 16.41 | ≤ 0.001 |

| H3 | Compassion satisfaction -> burnout | −0.35 | 0.09 | 3.75 | ≤ 0.001 |

| H4 | Burnout -> secondary traumatic stress | 0.96 | 0.05 | 20.04 | ≤ 0.001 |

| R2 | p values | Q2 | |||

| Burnout | 0.12 | 0.062 | 0.04 | ||

| Secondary traumatic stress | 0.93 | ≤ 0.001 | 0.31 | ||

| Compassion satisfaction | 0.54 | ≤ 0.001 | 0.21 | ||

| SRMR | Original sample | 95% | 99% | ||

| Saturated model | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | ||

| Estimated model | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 | ||

The goodness of the model is evaluated based on the strength of each structural path, as indicated by the R2 values for the dependent variables [44]. A value of R2 equal to or greater than 0.1 is considered acceptable [45]. In this study, all R2 values are above 0.1, indicating a satisfactory predictive capability of the model. Additionally, the predictive relevance of the endogenous constructs is determined by Q2 values. A Q2 value above 0 indicates that the model has predictive relevance. The results demonstrate significant predictive power for the constructs, as shown in Table 4. Furthermore, the model fit was assessed using the standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR). In this study, the SRMR value was 0.073, which is below the threshold of 0.10 or 0.08, indicating an acceptable model fit [46].

Further assessment of the goodness of fit and hypotheses were tested to ascertain the significance of the relationship. H1: Resilience has a significant effect on STS. The results revealed that resilience has no significant impact on STS (β = −0.03, t = 0.38, p = 0.704). Thus, H1 was not supported. In H2: Resilience has a significant effect on CS (β = 0.73, t = 16.41, p ≤ 0.001). Therefore, H2 was supported. In H3: CS has a significant effect on BO (β = −0.35, t = 3.75, p ≤ 0.001), So, H3 was supported. In H4: BO has a significant effect on STS (β = 0.96, t = 20.04, p ≤ 0.001), So, H4 was established.

3.3. Mediation Analysis

Mediation analysis was conducted to examine the mediating effects of CS and BO (Figure 3). The results, as presented in Table 5, indicate that CS and BO play a full mediating role (β = −0.25, t = 3.41, p ≤ 0.001). This suggests that CS and BO significantly mediate the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable.

| Total effect | T | Sig | Direct effect | T | Sig | Indirect effects | Effect | T | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience -> STS | −0.27 | 3.42 | ≤ 0.001 | −0.03 | 0.38 | 0.704 | Resilience -> CS -> BO | −0.26 | 3.55 | ≤ 0.001 |

| CS -> BO -> STS | −0.34 | 3.60 | ≤ 0.001 | |||||||

| Resilience -> CS -> BO -> STS | −0.25 | 3.41 | ≤ 0.001 |

- Abbreviations: BO, burnout; CS, compassion satisfaction; STS, secondary traumatic stress.

4. Discussion

This study examines the relationships between resilience, CS, BO, and STS using the SEM among mental health nurses. It evaluated a measurement model and a structural model to test a research framework. Reliability and validity were evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha, CR, and AVE. Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion and heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations. The structural model was assessed based on R2, Q2, and the significance of paths, with the goodness of fit assessed using SRMR.

In our study, the structural model produced an R2 value of 0.12 for BO, indicating that while resilience and CS significantly contribute to understanding BO among mental health nurses, additional factors are likely influential. Shdaifat et al. [25] employed SEM design to investigate the effects of work-related stress, CS, and job satisfaction on BO and STS among nurses, reporting an adequate model fit and significant direct effects. Similarly, Treglown et al. [47] evaluated a moderation-mediation model that incorporated resilience and BO, where model fit indices (e.g., CFI, RMSEA) substantiated the model, despite a significant chi-square statistic that can be attributed to the large sample size. Importantly, they identified that resilience, particularly when combined with diligence, served as a negative predictor of BO. In contrast, our study did not reveal a significant direct effect of resilience on STS, suggesting that resilience may exert its influence more indirectly through emotional and professional factors, such as CS and BO. The R2 value for BO in our model (0.122) was lower than those reported in the aforementioned studies, likely due to the omission of broader organizational predictors (e.g., workload, job control), which were included in prior research. Furthermore, cultural differences may have affected how participants in our Saudi sample perceive and report resilience or trauma-related stress, potentially influencing the responsiveness of the scales employed. These variations underscore the necessity for culturally adapted instruments and the incorporation of contextual factors in future models to enhance predictive accuracy and theoretical relevance.

Cultural factors significantly influence the ways in which nurses experience and report resilience and BO. In collectivist societies, for example, resilience may manifest predominantly through interpersonal or spiritual coping strategies, which are not entirely captured by standardized assessment tools such as the CD-RISC-25. Furthermore, although resilience did not exhibit a statistically significant direct effect on STC, its impact seems to be mediated indirectly through CS and BO. This observation suggests that personal resources, such as resilience, primarily alleviate stress-related outcomes by enhancing professional fulfillment and reducing emotional exhaustion. Despite the modest R2 value, the model’s fit indices, including an SRMR value of 0.073, remain within acceptable thresholds, indicating that the overall model retains structural integrity. Future research should encompass a wider array of organizational and cultural variables and refine context-specific measurement instruments to enhance explanatory power and theoretical applicability.

The findings of the study indicated that while resilience did not directly impact STS, it did have a significant positive influence on CS. Additionally, CS demonstrated a significant negative impact on BO. Furthermore, the results revealed a significant positive relationship between BO and STS, indicating that higher levels of BO were associated with increased STS. The mediation analysis revealed that both CS and BO fully mediated the relationship between resilience and STS. Overall, the study demonstrated the predictive capacity and relevance of the model, with a satisfactory fit to the data.

This study revealed that although resilience did not significantly impact STS, it had a significant positive effect on CS, leading to a significant negative effect on BO. In other words, mental health nurses who reported a high level of resilience and experienced CS reported low levels of BO. Therefore, while this result contradicted the first hypothesis of the study, it supports the second and third hypotheses. This result is consistent with previous studies [16, 17]. However, this contradicts a study among Brazilian and Spanish health professionals [48]. The possible rationale for our result is that STS affects nurses’ confidence, and BO is linked to anxiety and fear of patient harm among mental health nurses. Thus, it is suggested that measures aimed at improving nurses’ resilience will lower BO by enhancing their CS.

Interestingly, the findings of this study also suggest that BO directly affects STS, indicating that a high level of BO encourages STS. This result confirms the fourth hypothesis of the study and is supported by other studies [11]. Resilience has been found to be negatively related to both BO and STS, indicating that resilience is a significant resource that can protect individuals from the negative consequences of work-related stress. The study also suggested that being open to new experiences, maintaining a sense of humor, and effectively coping with failure and life circumstances are considered vital protective factors.

Of particular importance, this study emphasizes the vital impact of psychological resilience as a protective factor for mental health nurses against work-related stress. This result is supported by previous studies among nurses [14, 49]. The possible explanation for this result is that various negative consequences associated with low resilience have been documented in previous studies, for instance, symptoms of intrusion and posttraumatic stress disorder [50, 51]. Most importantly, individuals with high levels of resilience are more likely to effectively manage stress and traumatic experiences [13]. It has been confirmed that nurses with high levels of resilience are better able to mitigate emotional exhaustion and employ more adaptive work stress reduction strategies [14]. Therefore, conducting longitudinal studies is highly recommended for future research to fully understand the protective role of resilience.

5. Study Limitations

Although this study presents significant findings, several limitations warrant acknowledgment. Firstly, the reliance on self-reported questionnaires may have introduced response bias. Secondly, the cross-sectional design constrains the ability to establish causal relationships between variables. Thirdly, as the study specifically targeted mental health nurses, the findings may not be generalizable to nurses in other specialties who engage with diverse patient populations and operate within varying clinical conditions and environments. Additionally, the use of convenience sampling may further limit generalizability. The cultural and institutional context of Saudi Arabia may also influence the findings, as factors such as mental health stigma, hierarchical workplace structures, and setting-specific stressors may shape nurses’ experiences differently compared to other countries.

Another limitation is the relatively low R2 value for BO, indicating that the model accounts for only a small proportion of the variance in BO. This finding underscores the necessity of investigating additional factors, such as coping strategies, emotional intelligence, or organizational support, that could enhance the model’s predictive power. Future research should consider employing longitudinal designs and objective measures to assess STS and to gain a deeper understanding of causal relationships. Furthermore, the exclusion of nurses in leadership positions enhanced the uniformity of the sample, but it constrained the understanding of their distinct stressors. Finally, further studies are encouraged to examine the protective roles of resilience and CS and to implement intervention studies evaluating preventive programs.

6. Recommendation and Implications for Practice

This study found that BO has a significant positive impact on secondary STS, underscoring the importance of addressing BO to mitigate its broader psychological consequences. The findings have several practical, educational, policy, and research implications. Practically, early recognition and timely intervention are crucial in preventing the escalation of BO and its associated effects. Interventions that promote psychological resilience, such as coping skills training, emotional support, mindfulness practices, healthy lifestyle habits, and engagement in meaningful activities, can empower nurses to manage stress effectively. Regular workshops focused on emotional regulation, and resilience-building may further support nurses’ mental well-being and enhance patient care.

Educationally, nursing curricula and continuing professional development programs should integrate training on stress management, emotional resilience, and coping strategies to prepare nurses from the outset of their careers. From a policy standpoint, healthcare organizations should adopt formal resilience-building programs that emphasize self-efficacy, social support, and effective stress management. Policies aimed at reducing workloads and ensuring adequate staffing are also essential to minimize BO. Finally, future research should include longitudinal studies to examine the causal relationships between BO, STS, and resilience over time. Evaluating the effectiveness of specific interventions or organizational policies in preventing BO will also offer more targeted guidance for evidence-based practice.

7. Conclusion

This study aimed to explore the relationships between resilience, CS, BO, and STS among nurses using the SEM approach. Findings showed that resilience significantly enhanced CS. Additionally, CS had a significant negative impact on BO. There was also a significant positive correlation between BO and STS, which demonstrated that higher levels of BO were associated with more STS. Mediation analysis revealed that CS and BO fully mediated the relationship between resilience and STS. The study offers valuable insights into healthcare organizations and policymakers in developing strategies to enhance the resilience and CS of mental health nurses and prevent STS. Furthermore, incorporating interventions that address CS, such as mindfulness and self-care practices, can also be beneficial in reducing the risk of STS among mental health nurses.

Ethics Statement

The study received IRB approval from Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University under the reference number IRB (IRB-PGS-2022-04-148). Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

O.A.: conceptualization and collected data. A.A. and E.S.: methodology, data synthesis, management, and writing the first draft. All authors contributed to the final review of the article.

Funding

No funding was received for this manuscript.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.