Age Classifications of Young Adults With Chronic Illness: A Scoping Review

Abstract

Background: Young adults living with chronic illness have unique and complex needs related to their life stage. Currently, little clarity exists on what constitutes young adulthood, and the needs of young adults are often treated as equivalent to those of other developmental groups, particularly adolescents.

Purpose: To describe the impact of age classification as reported in research on young adults living with chronic illness.

Methods: A scoping review was performed by the investigative team. EMBASE, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science Core Collection were used to identify articles that met specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Summary statistics were used to describe articles included in the review.

Results: The initial search yielded 5028 articles and 482 articles were included in the final review. The age classification of young adulthood varied widely and no clear patterns of age range were noted. Of studies targeting only young adults, 100 different age classifications were reported and nearly a quarter of studies used a young adulthood age classification that was unique to the study. Over half of the included articles on young adults reported a minimum age of 18 years. More variability existed in the maximum age reported for young adulthood, with ages that ranged from 18 to 80 years. About half of the studies included young adults as part of a broader population.

Conclusion: A better delineation and classification of young adulthood in chronic illness is needed. Much of current research reports on the term young adulthood with little consistency in age classification, which can lead to false equivalency between studies.

1. Introduction

Erikson’s psychological stages of development [1] classifies young adulthood as a period of struggle between “intimacy” and “isolation,” typically between ages 18 and 40. During this time, young adults branch out to develop intimate relationships outside of their immediate family unit [1–3]. The transitionary nature of young adulthood is a crucial stage of psychosocial development, which can be complicated by chronic illness [4, 5]. This is due to factors including frequent hospitalizations, need for continued parental support, altered body image, newfound legal autonomy [6–8], uncertainty regarding employment, financial security, and maintenance of health insurance coverage [4, 9–16], and transitioning from pediatric to adult healthcare providers [17–19]. These factors can alter development of independence and forming of nonfamilial close relationships [20]. For these reasons, young adulthood is a unique life stage and additional considerations must be made when discussing care of young adult patients with chronic illness [21, 22]. Furthermore, despite there being notable biological [23, 24] and psychosocial [17, 18, 25] differences between children in late adolescence and legally autonomous adults, young adults are often combined with adolescents in research [26–30] under the broad term of “adolescents and young adults (AYAs).” While this practice can be appropriate based on the goals of a study, the age classification used in articles that focus on young adults has never been systematically examined.

Currently, there is a lack of consistency in age classification used to describe young adulthood in chronic illness. Some investigators allow for “young adult” participants up to age 80 [31] whereas others classify “young adulthood” as up to the age 18 [32]. While these investigators have identified their population as young adults, these studies clearly targeted patients in different life stages. Furthermore, there is little formal guidance or clarity from oversight organizations in how young adulthood should be classified. The World Health Organization classifies “young people” as those between ages 10 and 24 [33] while the United Nations classifies “youth” as those between ages 15 and 24 [34]. In the United States, the Society of Adolescent Health and Medicine defines young adulthood as being between the ages of 18 and 25 and notes that young adulthood is a period of “unique and critical” development [21]. Some [35–38] have used the term “emerging adulthood” coined by psychologist Jeffery Arnett, as a proxy for young adulthood. Per Arnett, emerging adulthood occurs between the ages 18 and 25 and is a period distinct from the broader period of young adulthood [25]. In addition, while the field of oncology has developed a formal definition of adolescents and young adults [39–41] (ages 15–39) [42], this has not occurred in other specialties. Given the unique developmental and psychosocial factors that impact young adults with chronic illness, it is imperative that we clearly define young adulthood to develop a widespread understanding of this specific population. Therefore, the purpose of this review was (1) to describe the age classifications reported in the literature on chronic illness in young adults and (2) to describe possible patterns related to differences in age classifications of young adults and in the treatment of young adulthood as a population distinct from children, adolescents, or other broader developmental populations.

2. Methods

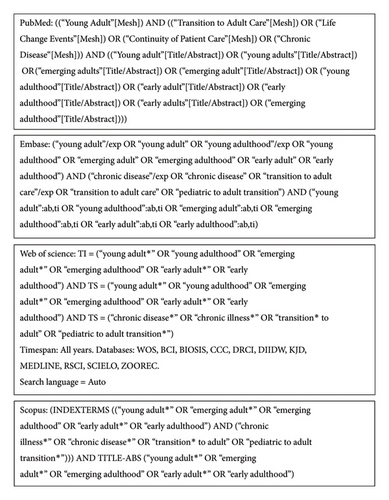

Given the broad nature of the research questions [43], we performed a scoping review of the available literature on young adults with chronic illness. Search engines included EMBASE, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science Core Collection. The search strategy (Figure 1) was developed with the guidance of an experienced research librarian. Controlled vocabulary words and synonymous free text were used in each search to find articles that focused on chronic illness and included patients identified as young adults. Conditions were selected based on the literature of commonly occurring chronic conditions in children and young adults (Table 1). The syntax was adjusted for each search engine.

| Medical service | Included conditions |

|---|---|

| Oncology | All cancers |

| Endocrinology | Diabetes (types I and II) |

| Hematology and immunology | Anaphylactic allergies, hemophilia, HIV/AIDS, sickle cell disease, solid organ transplant, stem cell and bone marrow transplant, thalassemia |

| Neuromuscular conditions | Cerebral palsy, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, spina bifida |

| Cardiac conditions | All congenital heart diseases |

| Gastrointestinal conditions | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Rheumatological conditions | Lupus, rheumatoid arthritis |

| Psychiatric conditions | Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder |

| Congenital conditions | All genetic abnormalities |

| Respiratory conditions | Asthma, cystic fibrosis |

| Multiple conditions | Any studies that included multiple included conditions |

Articles were included if they (a) were data based (either qualitative or quantitative research) and reported a clear research purpose (or purposes), methods, and results, (b) stated that the study sample included young adults or young adults in a commonly used proxy term, such as “emerging adults,” “transition age adults,” or “youths,” (c) focused on at least one of the included common chronic conditions in children and young adults, (d) provided an age classification for the study sample, (e) were published between January 2011 and November 2020, and (g) were published in English. The search criteria were intentionally broad to ensure an expansive yield of chronic illness articles to address the aims of the study. We limited our search to articles published after 2010 given increased recent discussions of the concept of young adulthood and a proliferation of articles focused on young adults in the last decade. Articles were excluded if the study was (a) about biological aspects of development or disease processes, (b) treated young adults as part of a general adult population, or (c) focused on provider or family caregiver experiences. Articles focused on provider or family caregiver experiences were excluded since they did not focus on patients and rarely provided complete demographics of the young adults involved. Titles and abstracts for all identified articles were reviewed for relevance. Full texts of all relevant articles were reviewed by two reviewers until consensus was reached based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Duplicate texts were excluded.

2.1. Data Abstraction and Analysis

Articles were categorized by included conditions, study continent, study design, sample size, year of publication, general study purpose, and if young adults were targeted as a distinct population or if they were included as part of a larger population, such as “adolescents and young adults.” We also recorded the age classification used for each study. Chronic conditions were categorized based on the body system or disease category to describe possible patterns in how different medical specialties classify young adulthood. The study purposes of the included articles were based on the main purposes of a subset of 100 articles and classified as (1) to investigate, describe, or evaluate a concept, phenomenon, or relationship, (2) to describe the process of transition to adult care, (3) to describe or evaluate routine care and/or a new intervention/tool, (4) to describe specific characteristics of the population of interest, or (5) to develop a novel concept or intervention. We did not conduct quality evaluation of each article because of the diverse use of methods. Data were extracted from each article and summarized using descriptive statistics. As this study did not involve human subjects, IRB approval and other ethical considerations were not needed.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

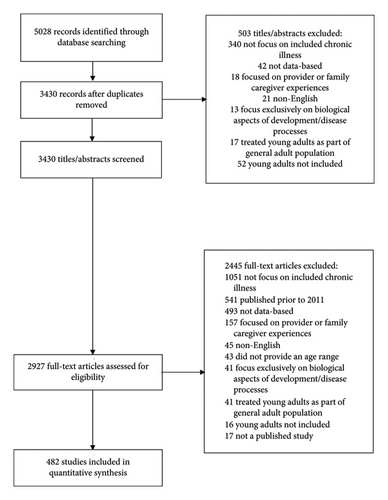

The initial search yielded 5028 articles. After application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 482 articles remained (Figure 2). Table 2 presents an overview of articles by the targeted developmental stage. Approximately half (53.1%) of the articles focused on young adults as a distinct population (i.e., they were not combined with another developmental population or age group such as adolescents or all adults). Most articles (85.4%) that included young adulthood as part of a larger population focused on adolescents and young adults as the population of interest. Articles on young adults focused primarily on those with an endocrine (23.0%), neuromuscular (14.5%), oncological (14.5%), or hematological or immunological (14.1%) condition. Articles on adolescents and young adults primarily included patients with an oncological (28.0%) or hematological or immunological (15.0%) condition or patients with multiple included conditions (15.0%).

| Young adults as distinct population (N = 256) | Young adults combined with another population (N = 226) | Full sample (N = 482) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescents and young adults (N = 193) | Other combined population (N = 33) | |||

| Included ages | 12–80 years | 8–72 years | 0–41 years | 0–80 years |

| Included chronic condition | ||||

| Cancer | 37 (14.5%) | 54 (28.0%) | 2 (6.1%) | 93 (19.3%) |

| Endocrine | 59 (23.0%) | 13 (6.7%) | 7 (21.2%) | 79 (16.4%) |

| Hematological/immunological | 36 (14.1%) | 29 (15.0%) | 7 (21.2%) | 72 (14.9%) |

| Neuromuscular | 37 (14.5%) | 20 (10.4%) | 6 (18.2%) | 63 (13.1%) |

| Psychiatric | 19 (7.4%) | 7 (3.6%) | 2 (6.1%) | 28 (5.8%) |

| Cardiac | 10 (3.9%) | 10 (5.2%) | 3 (9.1%) | 23 (4.8%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 10 (3.9%) | 11 (5.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 21 (4.4%) |

| Rheumatologic | 9 (3.5%) | 8 (4.1%) | 1 (3.0%) | 18 (3.7%) |

| Respiratory | 6 (2.3%) | 8 (4.1%) | 1 (3.0%) | 15 (3.1%) |

| Congenital | 9 (3.5%) | 4 (2.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (2.7%) |

| More than one condition | 24 (9.4%) | 29 (15.0%) | 4 (12.1%) | 57 (11.8%) |

| Study continent | ||||

| North America | 158 (61.7%) | 121 (62.7%) | 18 (54.5%) | 297 (61.6%) |

| Europe | 67 (26.2%) | 42 (21.8%) | 11 (33.3%) | 120 (24.9%) |

| Oceania | 11 (4.3%) | 19 (9.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 30 (6.2%) |

| Asia | 8 (3.1%) | 6 (3.1%) | 1 (3.0%) | 15 (3.1%) |

| Africa | 5 (2.0%) | 2 (1.0%) | 3 (9.1%) | 10 (2.1%) |

| South America | 3 (1.2%) | 2 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (1.0%) |

| Multiple | 4 (1.6%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (1.0%) |

| Study design | ||||

| Descriptive | 215 (84.0%) | 175 (90.7%) | 30 (90.9%) | 420 (87.1%) |

| Cohort | 78 (36.3%) | 77 (44.0%) | 14 (46.7%) | 169 (40.2%) |

| Cross-sectional | 75 (34.9%) | 72 (41.1%) | 11 (36.7%) | 158 (37.6%) |

| Qualitative | 62 (28.8%) | 25 (14.3%) | 4 (13.3%) | 91 (21.7%) |

| Systematic review | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (3.3%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| Intervention | 17 (6.6%) | 9 (4.7%) | 2 (6.1%) | 28 (5.8%) |

| Randomized controlled trial | 17 (100.0%) | 7 (77.8%) | 1 (50.0%) | 25 (89.3%) |

| Prepost | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (50.0%) | 3 (10.7%) |

| Mixed methods | 24 (9.4%) | 9 (4.7%) | 1 (3.0%) | 34 (7.1%) |

| Study sample size | ||||

| 3–999 | 229 (89.5%) | 169 (87.6%) | 26 (78.8%) | 424 (88.0%) |

| 1000–9900 | 10 (3.9%) | 15 (7.8%) | 5 (15.2%) | 33 (6.8%) |

| 10,000–99,000 | 10 (3.9%) | 5 (2.6%) | 2 (6.1%) | 17 (3.5%) |

| Over 100,000 | 2 (0.8%) | 4 (2.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (1.2%) |

| Sample size not provided | 2 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.4%) |

| Year of publication | ||||

| 2011–2015 | 94 (36.7%) | 62 (32.1%) | 8 (24.5%) | 164 (34.0%) |

| 2016–2020 | 162 (63.3%) | 131 (67.9%) | 25 (75.8%) | 318 (66.0%) |

| Overall study purpose | ||||

| To investigate, describe, or evaluate a concept, phenomenon, or relationship | 94 (36.7%) | 74 (38.3%) | 12 (36.4%) | 180 (37.3%) |

| To describe the process of transition to adult care | 58 (22.7%) | 37 (19.2%) | 4 (12.1%) | 99 (20.5%) |

| To describe or evaluate routine care and/or a new intervention/tool | 49 (19.1%) | 32 (16.6%) | 7 (21.2%) | 88 (18.3%) |

| To describe specific characteristics of the population of interest | 45 (17.6%) | 33 (17.1%) | 6 (18.2%) | 84 (17.4%) |

| To generate future research or interventions | 10 (3.9%) | 17 (8.8%) | 4 (12.1%) | 31 (6.4%) |

3.2. Young Adult Age Classifications

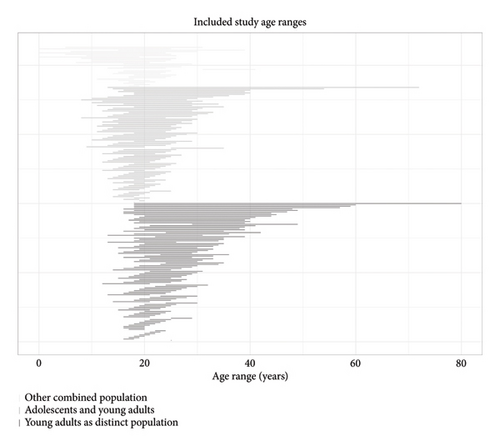

The age classifications reported in the selected articles are shown in Figure 3. Of articles focused only on young adults, there were 100 different age classifications reported with 22.7% of exclusively young adult focused articles using an age classification unique to that study. Articles that focused exclusively on young adults allowed for participants between the ages of 12 [44] and 80 [31]. The minimum allowed age in these articles was from 12 [44] to 29 [45] and the maximum allowed age was from 18 [32] to 80 [31]. Most articles on exclusively young adults used a minimum age of 18 (52.3%), 19 (11.7%), or 16 (9.8%). Fifteen different minimum ages were reported in these articles; 0.8% of the articles reported a minimum age unique to the article. Most articles on exclusively young adults used a maximum age of 25 (21.1%) or 30 (17.2%). Thirty three different maximum ages were reported in these articles; 3.1% of the articles reported a maximum age unique to the article. The most common age classifications for young adulthood were 18–25 years (12.1%) and 18–30 years (10.9%).

3.2.1. Patterns in Young Adult Age Range Variations

The most common age classification reported for young adult oncology patients was 18–39 (21.6%). The most common age classification reported for young adults with endocrine (18.6%) or hematological or immunological (11.1%) conditions was 18–30. The most common age classification reported for young adults with neuromuscular conditions was 18–25 (23.5%). Among articles on young adults with gastrointestinal conditions, 60.0% reported the age classification of 18–25 years (30.0%) or 18–29 years (30.0%). No commonly reported age classifications for young adults with congenital, cardiac, psychiatric, rheumatological, or respiratory conditions or those with multiple conditions were noted.

Articles that included patient data from North America (14.6%) and Oceania (27.3%) often reported the age classification of 18–25 years whereas studies from Europe (14.9%) or from multiple countries (75.0%) often reported the age classification of 18–30 years. No commonly reported age classifications were noted in studies conducted in Asia, Africa, or South America. Cohort studies frequently (14.1%) reported an age classification of 18–30 years. Qualitative studies frequently (16.1%) reported an age classification of 18–25 years. In randomized controlled trials, 35.2% reported an age classification of 15–30 years (17.6%) or 18–30 years (17.6%). In mixed-methods articles, 20.8% reported an age classification of 18–25 years (12.5%) or 18–24 years (8.3%). No commonly used age classifications were noted in cross-sectional studies focused on young adults. Articles that described the process of transition to adult care (15.5%) or aimed to develop a novel concept or intervention (40.0%) frequently reported an age classification of 18–25 years. No commonly reported age classifications for young adulthood were noted in other study types. No commonly reported age classifications were noted based on sample size or publication year.

3.2.2. Classification of Young Adults With Other Ages

Articles that reported on oncological (39.8%), respiratory (40.0%), multiple (42.1%), or cardiac (43.5%) conditions were less likely to focus on young adulthood as a distinct population. Articles that reported on endocrine (74.7%), congenital (69.2%), or psychiatric (67.9%) conditions were more likely to focus on young adults exclusively. Articles from Oceania were more likely to combine young adults with adolescents (63.3%) than articles from other continents. Articles from multiple countries almost exclusively (80.0%) focused on young adults as a distinct population. The majority (68.1%) of qualitative articles focused on young adults as a distinct population. All articles that reported a prepost design and all systematic reviews combined young adults with another age group. The majority (70.6%) of mixed-methods studies reported exclusively on young adults. Articles that reported on the development of a novel concept or intervention were less likely (32.3%) to focus on young adults exclusively. Differences in combining young adults with other developmental populations were not noted by the sample size or publication year.

4. Discussion

In a review of 482 articles on young adults with common chronic illnesses of childhood and young adulthood, we found little consistency in the age classification used to describe young adulthood. Articles that discussed the care of a sample including young adults allowed for study participants ranging from birth [46–48] to 80 years of age [31]. Nearly a quarter of the articles focused on young adults used a unique age classification not used by other articles focused on young adults. In addition, less than a quarter of articles that focused on young adults used one of the two most common age classifications for young adulthood. This indicates a lack of consistency in how the term “young adulthood” is operationalized across studies. While the study that included participants up at age 80 years explained that this was due to a change in the goal of sampling from conception of the study to recruitment, the population is inconsistently referred to in the text as being comprised of “young adults” [31]. While a single definition of age for young adulthood may not be appropriate for all studies and there can be times when looking at a broader population, such as adolescents and young adults, can be appropriate based on the aims of the study, this review demonstrates the wide variations in how age is classified for young adulthood. We found that some agreement exists in the lower bounds of young adulthood, typically designated at age 18 when legally capable patients in many countries can make their own medical decisions. There was little consistency in the maximum age of young adulthood, and little evidence of clear patterns in the age classifications reported for young adulthood.

We also found that nearly half of the articles reporting on young adults with chronic illness treated young adults as a subset of a larger population, primarily adolescents and young adults. While this approach can be appropriate, there are fundamental biological and psychosocial differences between adolescents and young adults that must be considered [12, 23, 24, 49]. For example, young adults with chronic illness are often navigating their roles as romantic partners, parents, and household financial contributors [14], which are not common concerns facing adolescents. The practice of treating young adults with chronic illnesses as equivalent to adolescents was especially common in articles that reported on cardiac, respiratory, and oncological conditions and those that reported on patients with multiple conditions. Further research is needed to determine why investigators in these disease-specific populations may choose to pursue a more broadly defined sample and if this is the best approach for generating meaningful results. Regardless, treating young adults, a population with their own unique needs and concerns, as a subset of a larger population should not be the default without clear and intentional purpose. The term young adulthood should be used in research studies but with intentionality and context to describe specific populations.

4.1. Implications for Research

Having clearly defined and consistent terminology is important in generating research that can be disseminated and discussed in the context of similarly relevant research. While young adulthood may be a fluid and variable period, a consensus is needed around what constitutes the period of young adulthood and what constitutes appropriate use of this term. While our review described use of the term across articles that reported on selected chronic illnesses, we were unable to better understand reasons for variations in how the term young adulthood was delineated without more intimate knowledge of each individual study. Future research should focus on the rationale used by researchers to classify the age of young adults. The period of young adulthood has unique considerations with regards to developmental stages and life concerns. Such practice of using “young adulthood” as a general term to refer to patients in a transitionary period from pediatrics to adulthood should be avoided as this practice conflates a clinical event with a developmental life stage. While the transition from pediatric providers to adult providers can occur in young adulthood, this is not always the case, and clinical transition-focused research is not synonymous with broader young adult focused research. Ideally, this review can provide future researchers with some clarity on how age has been classified in articles that report on young adults with chronic illnesses and assist researchers in determining appropriate target populations for future research on young adults. While the scope of this review did not allow us to make recommendations for how the term young adulthood should specifically be operationalized, future policy work should focus on identifying key components to identify the young adult period and develop recommendations and guidelines for how and when this term should be used in research studies. Considerations should include age of legal maturation, established indicators of transition from child to adult [50, 51], specific healthcare facility transition (i.e., transfer) policies, and cultural considerations. Given the individual and society specific nature of many of these considerations, multiple definitions may be required, though increased specificity and precision in the use of this term is required overall.

4.2. Implications for Practice

There is also a lack of consistency in young adulthood in clinical practice [18, 52, 53]. Given that the young adult period is typically when patients transition from pediatric to adult providers, this is concerning as young adults may be lost to follow-up without support [54, 55]. While this review found that the main purpose of roughly 25% of the articles on young adults was to describe the process of transition to adult care, there was little consistency found in the reported age classifications. The use of clear and intentional definitions for the term “young adulthood” will improve clinical care through research that providers can apply to their practice to further address the unique challenges faced by young adults living with chronic illness.

4.3. Limitations

This review had a few limitations. First, this was a scoping review and as such, we did not grade the quality of the articles included which could have introduced reporting bias [43]. However, we believe this to be the first review of the literature to examine variations of age-based definitions in young adults with chronic illness. Second, our review focused on specific commonly occurring chronic conditions of childhood and young adulthood. We acknowledge that other classifications of young adulthood and/or the consistency of classifications could vary based on other conditions and/or disease processes.

5. Conclusions

Young adulthood is known to be a period of physical, psychosocial, developmental, and legal transition [4, 9–12, 17], which can be further complicated by chronic illness [4, 5]. As such, clear, intentional, and specific definitions are needed to allow researchers to identify young adults. Due to the complex period of transition inherent to young adulthood, cohesive definitions are needed in young adult focused research to adequately compare and synthesize findings across disciplines and populations. While the term “young adulthood” is often used to describe populations in pediatric and adult chronic illness literature, this term is often employed imprecisely and inconsistently and the period of young adulthood is often referred to by multiple interchangeably used terms [11, 12, 52, 56]. Furthermore, researchers seldom explain their applied criteria underlying the use of a specific term or age classifications [53, 57, 58], impairing the ability to accurately compare articles and potentially leading to false conflation of findings between groups that are assumed to be—but are not—similar. Some attempts have been made by specific disease disciplines, primarily oncology [39, 40, 42, 52], to standardize age classifications that encompass the young adult period but overall, there has not been widespread discussion of this issue. Furthermore, this review found that less than a quarter of oncology studies on young adults, or adolescents and young adults, used the agreed definition for age as noted in previous literature [59], which can lead to further confusion.

Overall, further understanding of young adulthood as a separate and unique period in the trajectory of life is needed. Currently, there is little discussion of young adulthood as a distinct life stage and even less discussion and clarity on how to delineate young adulthood. Those providing care to young adults need scientific evidence that addresses the specific physiologic and psychosocial needs of this vulnerable population and the complex challenges they face. While variations may exist within the broader scope of young adulthood based on clinical and research focuses, without a clear understanding of young adults as a distinct population in healthcare research, and a clear understanding of how this term is being applied in individual studies, practice and policy changes cannot occur.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors have nothing to report.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tatenda Mangurenje Merken, PhD, RN, for her assistance with article screening.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as this was a narrative review.