Patient-Reported Outcomes in Acute High-Risk Abdominal Surgical Patients: Postdischarge Telephone Follow-Up Calls

Abstract

Background: Knowledge of the recovery of acute high-risk abdominal (AHA) surgical patients after discharge is sparse. Discharge from hospital after emergency surgery can be a stressful experience due to serious illness, anxiety, pain, a life-changing situation and new information. At discharge, patients may not fully comprehend the situation, and worries about how to cope at home without professional help may prove stressful.

Aim: The aims of this study were to explore how patients undergoing AHA surgery experienced their physical and mental status during the first month after discharge and possible returning to daily activities and work, as well to explore whether nurse-led telephone follow-up was feasible after acute high-risk surgery.

Method: A single-centre prospective study with an exploratory descriptive design. A total of 91 patients participated in the study. Quantitative data were collected using telephone follow-up calls. Data were analysed using descriptive statistics.

Results: The main problem for patients was severe fatigue, but most patients regained normal life within 30 days after discharge. Patients’ positive statements about receiving a phone call after discharge and other findings demonstrate the feasibility of nurse-led telephone follow-up calls.

Conclusion: Knowledge of how patients recover following AHA surgery can facilitate the targeting of discharge information to patients’ needs. Our study indicates that telephone follow-up calls were feasible and beneficial for patients’ convalescence, but whether follow-up affects the patient course regarding readmittance and complications needs to be investigated in the future. Contact to a nurse in the surgical specialty of gastroenterology seems to be important and can benefit patients’ convalescence.

1. Introduction

Acute patients treated with emergency abdominal surgery carry a risk of postoperative complications, prolonged hospital stay and mortality [1–4]. Standardised care-bundles have reduced these risks [5, 6], but emergency surgery still involves a high risk of a challenging postoperative period. At the Gastro unit, Copenhagen University Hospital Hvidovre, a well-established multimodal, standardised protocol is applied to patients undergoing acute high-risk abdominal surgery (AHA patients). AHA patients are patients treated for perforated viscus, bowel ischaemia or obstruction [1]. Optimising the perioperative course in a consecutive prospective cohort of 600 patients significantly reduced 30-day mortality by a third. Continued focus has yielded a further decrease in mortality, with a 30-day mortality of 9.2% in a newer cohort of AHA patients [7].

In the recent years, there have been a stronger focus on optimising the early postoperative course (postoperative day 1–17), focussing on early and intensive mobilisation, pain management and respiratory optimisation, leading to increased physical activity level, less pain and fewer postoperative pulmonary complications in patients undergoing AHA surgery [8].

Only a few studies have focused on patients’ own experiences of undergoing AHA surgery and the postoperative recovery period [9]. A small study of self-reported quality of life (QoL) in the elderly 6 months after discharge conducted at the Gastro unit, Copenhagen University Hospital Hvidovre, showed good results overall, as most patients returned to their own homes and stated well-being despite reduced physical ability [10]. The study focused on patients > 75 years.

A systematic review has examined the effects of nurse-led post-operative telephone follow-up on patient outcomes [11]. Two articles focused on acute patients in orthopaedic surgery and trauma, respectively. The remaining articles concentrated on elective surgery and medical patients. All 10 articles found that patient satisfaction increased when patients were contacted after discharge. Only two articles on gastroenterology were included [11]. One of the studies was a randomised controlled trial, and the patients in the study group received telephone follow-up from a stoma nurse after hospital discharge. The telephone follow-up focused on general clinical status, especially stoma complications and stoma self-care ability [12]. The study indicated that patients who received a telephone call after discharge were more satisfied than those who did not. Additionally, they had significantly better ostomy adjustment and fewer stoma complications than those in the control group.

Discharge from hospital after emergency surgery can be an anxiety-provoking and stressful experience due to a complex patient course, serious illness, anxiety, pain, a life-changing operation (for example, stoma), much new information and perhaps new restrictions. At discharge, patients may not fully comprehend the new situation and worries about how they will cope at home without professional help can be stressful [10, 13, 14]. A study of QoL in the elderly showed that it was difficult for elderly patients to comprehend the nature of the treatment course, including surgery. Structured follow-up may help such patients understand and cope with the often very stressful admittance [10]. The AHA patient course after discharge has not been investigated thoroughly, which makes it difficult to inform patients what they may expect in terms of, for example, performance and fatigue after discharge. Further studies of the period after discharge from the patient’s point of view could provide important knowledge that improves current understandings and makes it possible to target interventions to the course after discharge.

The aims of this study were to explore how patients undergoing AHA surgery experienced their physical and mental status during the first month after discharge and possible returning to daily activities and work, as well to explore whether nurse-led telephone follow-up was feasible after acute high-risk surgery.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

This was a single-centre prospective study with an exploratory descriptive design.

2.2. Setting and Participants

The study was conducted at the Gastro unit, University Hospital Hvidovre, Capital Region of Denmark. The Gastro unit has a specialised ward that optimises postoperative care following AHA surgery. All patients were treated with a standard protocol bundled emergency care, from admittance, diagnosis, care and treatment and perioperative goal-directed fluid therapy and were postoperatively stratified into high- or low-risk care in an intensive care unit or specialised ward. At the postoperative ward, patients were treated with a standard care plan that included continuous vital signs monitoring for 3 days and pain and nausea treatment, early mobilisation, oral nutrition and fluid therapy according to the standard care plan at our unit. The population were the group of AHA patients who were directly stratified to the AHA ward.

All AHA patients were screened for eligibility from January to December 2021. Inclusion criteria were age 18 years or above with suspected abdominal pathology requiring immediate emergency laparotomy or laparoscopy, including reoperations after elective gastrointestinal surgery and reoperations after previous non-AHA surgery (perforated viscus, intestinal obstruction and ischaemia, intra-abdominal bleeding and anastomotic leakage). Exclusion criteria were patients undergoing the following procedures: appendectomies, negative laparoscopies/laparotomies, cholecystectomies, simple herniotomies following incarceration without bowel resection, reoperation owing to fascial separation with no other abdominal pathology identified, internal hernia after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery, subacute surgery (surgery planned within 48 h) for inflammatory bowel diseases and subacute colorectal cancer surgery [1].

Patients not able to provide informed consent or who were unable to manage telephone calls due to language or mental disability were excluded. Also, patients who did not answer second telephone call were excluded from the study.

The demographics of the population were extracted from the patient records (illustrated in Table 1).

| Variable | All participants: n = 88 No (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 38/50 (43/57) |

| Age (years, median) | 65 (27–94 years) |

| Profession | |

| Pensioner | 55 (63) |

| In work | 29 (33) |

| Unemployed | 3 (3) |

| Student | 1 (1) |

| Preoperative residential status | |

| Own home | 85 (97) |

| Home care service | 6 (7) |

| Skilled nursing facility | 1 (1) |

| Nursing home | 2 (2) |

| Type of surgery (laparoscopy/laparotomy) | 29/59 (33/67) |

| ASA (American Society of Anaesthesiology) | |

| 1 | 6 (7) |

| 2 | 45 (51) |

| 3 | 36 (41) |

| 4 | 1 (1) |

| WHO/ECOG/(Zubrod score) | |

| 0 | 39 (44) |

| 1 | 37 (42) |

| 2 | 9 (10) |

| 3 | 3 (4) |

| 4 | 0 |

| Diagnosis | |

| Perforated viscus | 13 (15) |

| Obstruction | 73 (83) |

| Other (e.g., bowel ischaemia) | 2 (2) |

| Readmission < 30 days | 5 (6) |

2.3. Data Collection

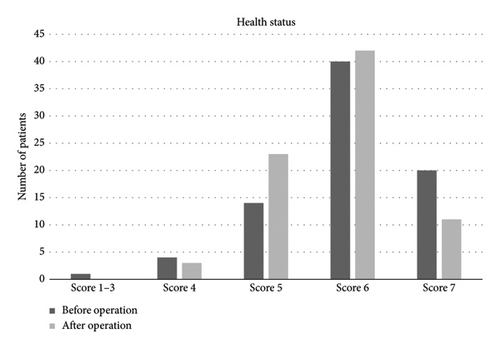

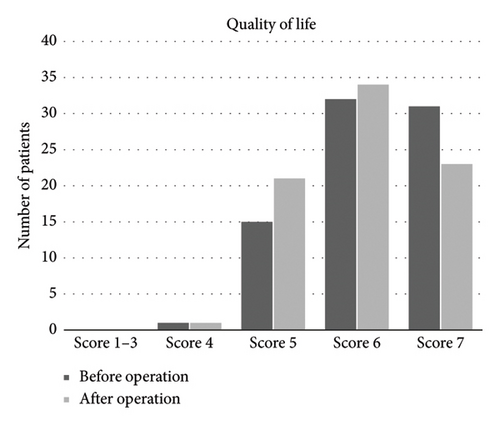

Data were collected via telephone follow-up calls 24–96 h and 30 days after discharge. The duration of the follow-up telephone calls was 10–30 min. All calls were made by the first author (JO). JO was a project nurse specialised in gastrointestinal surgery, but she was not involved in the daily care of the patients. The telephone calls were supported by a structured interview guide (illustrated in Table 2) with information on eating and drinking habits, fatigue levels, gastrointestinal function, pain assessment, daily activities, exercise routines and need for home assistance. Additionally, the follow-up telephone calls covered patients’ self-assessment of their health and well-being, which were structured into two categories: overall health status and quality of life asked as before and after the operation on a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 represented ‘very low/bad’ and 7 represented ‘very high/good’. This tool had been previously tested in another study [10]. Finally, patients were invited to add additional comments.

| 1. How are you doing? How did you feel about coming home? |

| 2. What is the status regarding: |

| Food/appetite and beverages (three levels: good–decreased–none) |

| Nausea or general discomfort (five levels: from none to constant) |

| Pain (scale from 0 to 10, where 10 is worst imaginable) |

| Fatigue (scale from 0 to 10, where 10 is worst imaginable) |

| Gastrointestinal function (levels of annoyances) |

| Exercise (five levels: active to confined to bed, walking, biking, making exercises) |

| Activity in everyday life (Zubrod score) |

| Need for home assistance now and before the operation |

| How would you estimate your overall health status? Asked before and after the operation (scale from 1 to 7, where 1 is ‘very low/bad’ and 7 ‘very high/good’) |

| How would you estimate your quality of life? Asked before and after the operation (scale from 1 to 7, where 1 is ‘very low/bad’ and 7 ‘very high/good’) |

| 3. Other comments |

Standardisation was achieved using the guide, and the sequence of questions asked during the call was in the same order and same questions were asked in both the first and second telephone calls.

To measure patients’ ability to carry out activities of daily living, a performance score, WHO/ECOG/Zubrod, was used [15] with ranges from 0 (fully active, able to carry on pre-disease performance without restriction) to 5 (dead) (Table 1).

All calls were initiated using a broad question regarding return to home, before asking the focal questions to gain a trusting contact and to be responsive to the patient’s own identification of any problems.

The structured interview guide for this study was tested by five patients prior to the study, and no adjustments were deemed necessary.

Data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the Gastro unit, Copenhagen University Hospital Hvidovre, Denmark [16].

All patients were invited to participate in the study during hospital stay. They received oral and written information in conformity with the Helsinki Declaration [17]. Patients then signed an informed consent form where they agreed to participate in telephone follow-up calls after hospital discharge.

It was emphasised that participation was voluntary and that the participants could withdraw without any negative consequences. The participants were guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality in conformity with the Helsinki Declaration [17].

The Danish ethical committee assessed that no approval was required according to Danish law as the study involved no biomedical intervention. Descriptive data regarding the surgery and health information were obtained from the Electronic Patient Record (Sundhedsplatformen) after the consent declaration had been signed. Approval was obtained from the Danish Data Protection Agency (ID no.: HVH-2013-014). The project was approved by the Centre for Regional Development—Health Research and Innovation, Knowledge Centre for Data Reviews (journal no: P-2020-1177).

2.4. Data Analysis

Quantitative data (patient-reported outcomes) were analysed using descriptive statistics. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviation, medians and interquartile ranges or frequency distributions, as appropriate.

3. Results

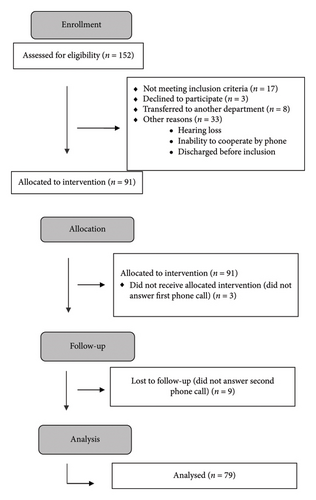

A total of 152 patients were assessed for eligibility, 61 of whom were excluded. Thereby, a total of 91 were allocated to intervention. Three patients did not answer the first phone call, and nine patients were lost to follow-up on day 30 due to unanswered phone calls, resulting in 79 patients receiving the allocated intervention. A flow diagram of participation and reasons for exclusion is presented in Figure 1.

Some follow-up calls could not be performed by telephone, especially in the elderly and frail group of patients, due mainly to hearing loss and inability to cooperate over the telephone.

The median age of all patients was 65 years (range 27–94 years); 38 (43%) were women and 50 (57%) were men. Twenty-nine (33%) of the patients were employed. On day 30, 18 (20%) had returned to full-time work, 3 (3%) worked part-time and 11 (13%) were on sick leave. The patients on sick leave reported that they had physically hard work such as driving or working in warehouses or institutions. All patients, except for three, lived in their own home. Two patients lived in a nursing home, and one was on a rehabilitation stay. Directly after discharge, 2 (2%) of the patients had a temporary stay in a nursing home and 5 (6%) of the patients were admitted to a rehabilitation stay, four of whom were newly admitted.

The mean length of stay in the hospital was 9 (2–73 days).

The patients had many worries related to loss of appetite and what they were supposed to eat. Thirty-six (40%) reported that their food intake decreased within the first days after discharge due to lack of appetite. After 30 days, 16 (18%) still reported diminished appetite.

Especially patients with stoma problems needed additional guidance within the first 30 days after discharge. On hospital admission, 10% (n = 9) of the patients already had a stoma and were used to managing daily life with a stoma. In the cohort, there was a high incidence of stoma construction of 25 (28%). Of those with a new stoma, 10 (40%) were considered as permanent. Gastrointestinal function was an issue for all the patients. Several reported changes in gastrointestinal function and provided responses in several categories. Eleven (13%) reported rumbling and stomach cramps after discharge. Thirty days after discharge, these symptoms had decreased. In the first days after discharge, 65 (71%) of the patients reported formed or soft stools, 11 (12%) had normal stools, 15 (17%) had loose stools and 4 (5%) had hard stools.

Thirty days after discharge, gastrointestinal function had improved, with more patients having formed or soft stools, and fewer patients experiencing loose stools or being bothered by rumbling and stomach cramps. However, 10% of the patients still experienced challenges in regulating defecation and primarily reported having hard stools.

Fatigue was another sequela that affected the patients’ lives after discharge. The patients’ statements on this topic related to mental fatigue and having difficulty coping with ordinary tasks. On a scale from 0–10 (NRS = numerical rank scale), they reported a median value of 4 (range 0–9) during the first days after discharge, which dropped to 1 (range 0–8) after 30 days. The patients did not experience many problems with pain. The median value for pain on a scale from 0 to 10 (NRS = numerical rank scale) was 4 (range 0–9) at discharge, and it decreased to 1 (range 0–8) after 30 days. The patients reported that resuming physical activity after discharge was a slow process. A total of 42% (n = 37) of the patients reported that they performed light outdoor activities, such as going for a walk or cycling in the first days after discharge. However, 51 (58%) of the patients had not been outside their home during the first days after discharge. Instead, they reported that they performed light activities at home such as walking around and doing leg exercises as well as cooking. Four patients reported that they were not physically active at all.

At 30 days after discharge, the patients’ physical activity level had increased. An improvement in the Zubrod score was seen in the group of patients with a score of 2 or more (spending up to 50% of waking hours in bed or being bedbound). Directly after discharge, 46 (52.5%) had a score above 2, while at 30 days after discharge, this had decreased to 25.3% (n = 22). Also, at 30 days after discharge, the performance status had increased, as 75% (n = 59) almost were fully active, except for doing heavy physical work.

Concerning their physical conditions, 37 (42%) of the patients reported doing light outdoors activity. Of these, 25 patients answered that they went for longer walks or were cycling in the first days after discharge. The rest of this group of patients (n = 12) took walks in their neighbourhood.

A total of 51 (58%) had not been outside the home but performed light activity indoors. Four patients who indicated that they were not active at all were also not active before the operation. After 30 days, 73 (92%) were living in their own home. Of these, 16 patients needed further physical training or help with daily living and received municipal support.

In the present study, patients experienced good self-reported QoL and health assessment after 30 days rated on statements about how they remembered feeling before the operation and afterwards. QoL and health were almost similarly rated right after discharge and after 30 days, though with a slight increase in patients’ assessment of QoL on day 30 (Figures 2 and 3).

All patients were thankful for being offered a telephone call and expressed that the call was useful to them. It provided a sense of security at discharge, and they said that having the opportunity to ask questions about unsolved issues helped them with the process of getting back to a normal life. Several patients expressed that it would have been appropriate with a call 2–3 weeks after discharge because this period was the most difficult especially due to fatigue, concerns about bowel function and stool pattern.

4. Discussion

This study highlights that acute high-risk emergency (AHA) patients experience many challenges in the weeks after discharge. Their performance after 30 days was quite good and was improving, and this study provides knowledge to encourage and inform patients before discharge, enabling better information regarding likely time of recovery and return to employment. Ward nurses have a central role to play in patients’ experience. They must understand the importance of dealing with the main postoperative problems such as pain, fatigue, mobilisation, nausea, eating, bowel function and returning to a preoperative way of living. Furthermore, encouraging patients to remain active after discharge is essential. The main challenges were severe fatigue and changed gastrointestinal function. These topics are important to inform about and discuss with the patient, preparing them for recovery, disseminating knowledge about what to expect and thereby improving their coping after discharge.

Many patients who undergo major emergency surgery experience a broad range of possible sequelae and complications [18]. Mental health recovery has not yet received much attention and has not been investigated on a large scale, and little attention has been devoted to studying patients’ need for outpatient follow-up and what effects follow-up can have on morbidity, somatic and psychological challenges. In relation to the question about fatigue, some of the patients also called it to be mentally exhausted and very tired, and it seems difficult to fully recover. Guiding them throughout hospitalisation and especially before discharge is an essential task for nurses. Meeting the patient’s problems and giving good advice strengthens health outcomes and improves the patient’s ability to manage daily life [13, 14].

There is a risk of requiring a stoma when undergoing major emergency surgery, and in this study, just under a third of the patients had a stoma performed due to life-threatening surgery. Coping with life-threatening and life-changing conditions presents a substantial mental challenge. All ostomy patients included in this study were offered contact to the stoma nurse and a visit in the outpatient clinic, if necessary. An RCT study concerning ostomy patients concluded that telephone follow-up can improve patient ostomy adjustment levels [12].

Discharge challenges for these acute surgical patients are many and complex; however, most patients were living in their own home after 30 days. The complex acute setting is unfamiliar to the patient, and they can find it difficult to comprehend and relate to new, sometimes life-changing information. Having health professionals nearby and the possibility of addressing issues when hospitalised can reassure patients. In contrast to hospitalisation, being at home in your own surroundings can be agreeable, but patients can also feel vulnerable at home [19]. A telephone call after discharge provides an opportunity to exchange information and support the patient’s ability to deal with signs of complications or other challenges and minimise the patient’s concerns. We learned, however, that not all elderly and frail patients, perhaps those who were hard of hearing or others who were unable to cooperate over telephone, were able to benefit from the telephone call. It would be advantageous to identify patients who can receive calls and to assess who would benefit from physically attending in an outpatient setting.

A systematic review has investigated readmissions and prevention of complications, but no conclusive evidence exists that telephone calls can prevent this [11]. Readmission is complex and depends both on each patient’s ability to react to relevant symptoms and deal with problems and on the competence and ability to manage patients at community level outside the hospital. On the other hand, several studies have identified a significant difference in patients’ assessment of their own perception of managing problems related to their disease [11, 12].

Our results are in line with those of other studies; many patients speculated about how they could manage daily life after discharge [9, 19]. Because of fatigue in general and for people with hard physical work, it took more than a month before they were back to normal physical levels and working. More than half of the employed patients worked again after 3–4 weeks.

The fact that it was possible for the patients to have their questions answered and that they were thankful for the opportunity to discuss their hospitalisation indicates that conversation either over the phone or as an outpatient will help patients gain better understanding of their recovery process. It will also facilitate their ability to manage the overwhelming experience that patients in this and other studies have expressed [9]. Preparing patients better before discharge is important in the context of the present findings, carrying significant relevance for the ongoing development and enhancement of nursing care practices tailored to this specific patient category.

Knowledge must be incorporated to inform patients, adjust written material and improve the future planning, care and treatment of these patients in the postoperative course and especially at discharge. Optimising the transition is important and imperative for patients.

A large number of patients undergoing AHA surgery will experience sequelae [18]; our results indicate that such sequelae can be detected and managed if patients are offered a structured follow-up system. The potential for improving postoperative care, possibly worldwide, is considerable. This article indicates that there is potential for improving self-management and reducing post-discharge problems in AHA patients, and for improving patients’ feeling of security about transitioning to everyday life. Furthermore, one could speculate whether follow-up could address issues and treat otherwise unknown sequelae, possibly reducing the need for readmissions and potentially morbidity and mortality. Providing patients with the possibility of addressing unresolved issues could help them to manage better their everyday lives. More studies are needed to address these issues, including how interventions like follow-up can help patients navigate life-threatening circumstances.

5. Methodological Considerations

This population was a selected group of patients within the AHA cohort. The group probably performed better than if the sickest patients had been included. Although not validated, the questionnaire in the interview guide developed for this study was tested by five patients before the study. The specific health and QoL questions have proven useful in a previous study, providing us with information on how patients are doing after discharge [9]. We have gained new perspectives on the patients and their physical and mental status postoperative which can be utilised in future AHA courses. We now have insight into what they can expect. All telephone calls were made by a nurse specialised in gastrointestinal surgery who was not involved in day-to-day care, which could make it easier for patients to talk freely about their experiences during hospitalisation. In all, 12 patients did not answer the telephone call. However, the patients who answered were representative for the AHA group as they included both young and old patients, men and women. The median age of the patients in this study corresponds well with an earlier larger AHA cohort of 600 patients with a median age of 68 years [1]. The number of patients promotes the credibility of the study. However, this study is based on one group and findings should be interpreted with caution.

6. Conclusion

The results of this study provide researchers and clinicians with important information regarding the physical and mental status after discharge of acute patients who were treated with emergency high-risk abdominal surgery. This study provides knowledge to share with patients before discharge. Furthermore, it is underlining the importance of informing patients of changes in gastrointestinal function upon discharge. The impact of structured follow-up on patients’ physical and mental status, as well as the handling of complications after discharge, needs to be investigated further.

It was possible to get answers to the questions included in the questionnaire though some follow-up calls could not be performed by telephone, especially in the elderly and fragile group of patients due to hearing loss and inability to cooperate by telephone. It is necessary to screen patients before making the telephone call. Also, patients’ needs for follow-up seemed to differ. However, most patients found the follow-up beneficial, suggesting the value of structured caretaking after discharge in this group of patients. Patients experienced challenges, especially during the first weeks after discharge, indicating that the need for guidance and potential management of complications was highest during the early phase of the investigated period. Significant improvements were observed during the third and fourth weeks after discharge. It was confirmed that the majority of those who were employed were able to return to work despite having undergone major emergency surgery. We found that identifying which patients needed further evaluation can be performed at this point by an experienced specialised nurse. Contact to a nurse in the surgical specialty of gastroenterology seems to be essential, either via attendance in an outpatient context or telephone follow-up. However, more studies need to be done in this field to explore patients’ somatic and psychological sequelae to better understand the consequences for patients who undergo AHA surgery.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, private or not-for-profit sectors.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.