Structure and Evolution of the uqcrfs1 Gene in Western Palearctic Water Frogs (Genus Pelophylax) and Implications for Systematics of Eastern Mediterranean Species

Abstract

The Rieske protein, encoded by the nuclear uqcrfs1 gene, is an essential subunit of the cytochrome bc1 complex involved in electron transfer. Despite its vital function, studies on the structure and evolution of the uqcrfs1 gene are limited. In particular, data on the fine-scale evolution of the uqcrfs1 in the context of speciation and adaptation are lacking. Eastern Mediterranean water frogs (genus Pelophylax) are an ideal model for studying such evolutionary processes at the molecular level, as they comprise several closely related lineages with different degrees of genetic and organismal divergence. Based on comprehensive sequence data of 137 frogs from 106 populations, including Mediterranean frogs as well as frogs from Europe and Central Asia, the spatial distribution of uqcrfs1 alleles was mapped and their genealogical relationships analyzed. In addition, the structure of the gene was investigated using genomic and transcriptomic data from Pelophylax lessonae. The uqcrfs1 gene consists of two exons. The length of coding sequence and its corresponding protein sequence is 807 nucleotides and 268 amino acids, respectively. The GC content and the G/C-ending codons of the gene are about 59.9% and 75.37%. The uqcrfs1 gene has a core promoter type similar to that of widely expressed housekeeping genes, with GC-rich blocks in the regulatory 5’ region, and contains many dispersed conserved motifs for transcription initiation. Genealogical analysis of the uqcrfs1 sequences revealed 10 allelic groups in the Eastern Mediterranean region. While the position of some allelic groups and the number of subgroups in the uqcrfs1 gene tree are somewhat different, they largely support the results of previous nuclear and mitochondrial genealogical studies. This gene is therefore an effective marker for determining the origin of different water frog species and lineages, including hybrids.

1. Introduction

Iron-sulfur (Fe-S) proteins are essential enzymes in both the tricarboxylic acid cycle and the electron transport complex within the mitochondria. Electrons are transferred from NADH and FADH and passed through several Fe-S proteins located in complexes I, II, and III of the electron transport complexes [1]. Some of these proteins contain both mitochondrial and nuclear-encoded subunits as is the case with complexes I and III. In contrast, complex II is composed solely of four nuclear-encoded core proteins [2]. The ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase uqcrfs1 (also named as Rieske Fe-S protein, RISP) is an essential subunit of the complex III (also known as ubiquinal: cytochrome c oxidoreductase or bc1 complex) in the mitochondria [3, 4]. Complex III is an enzyme complex that transfers electrons from ubiquinol to cytochrome c. In mammals, complex III has a symmetrical dimeric structure and each of its monomers consists of 10 distinct subunits. Of these subunits, one is encoded by mitochondrial DNA (CYB) and the others by nuclear genes [5–7]. Three of these subunits, cyb, cyc1, and uqcrfs1, have catalytic properties and are therefore involved in electron transfer.

In humans, the uqcrfs1 gene is located on chromosome 19. It consists of two exons and one intron. Exon1 encodes the mitochondrial targeting sequence, directing the transport of the protein to the mitochondria and exon2 encodes the Rieske domain of the Rieske protein [8]. The coding sequence (CDS) (exon1 and 2) is translated into a protein sequence of 254 amino acids (aas). Its 5′ untranslated region contains a G+C rich promoter with putative transcription factor binding sites and is ~148 nt in length. Its 3’ untranslated region is ~396 nt in length and lacks pol (A) and other known repeated elements [9]. As in humans and other vertebrates, the uqcrfs1 gene of the Central European water frog species Pelophylax lessonae (Camerano, 1882) and Pelophylax ridibundus (Pallas, 1771) consists of two exons and one intron. The CDS is 807 nt long and the corresponding protein sequence has a length of 268 aas in both species [10].

Recent studies have demonstrated the suitability of uqcrfs1 as a marker for genotyping water frogs, including their hybrids [11–13]. The objective of the present study was to evaluate the diversity of uqcrfs1 in Eastern Mediterranean water frogs representing different evolutionary lineages with varying phylogenetic ages, spanning from the Upper Miocene to the Pliocene and Pleistocene [14, 15]. In addition, the structure of the gene was analyzed, and putative regulatory elements were described. Using comprehensive sequence data, obtained from 137 frogs from 106 populations, the spatial distribution of uqcrfs1 alleles was mapped and their genealogical relationships were reconstructed. Based on these data, current hypotheses regarding the systematics of Eastern Mediterranean water frogs (e.g., Akın et al. [15], Plötner et al. [14], and Akın Pekşen [16]) were subjected to critical evaluation.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. The Sources of uqcrfs1 Gene Sequences

The uqcrfs1 nucleotide (nt) sequence of Xenopus tropicalis was downloaded from the UCSC Genome Browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/) (version UCB_Xtro_10.0 (GCF_000004195.4) (NM_203580.1 [17]), the nu sequences of Rana temporaria (XM_040329478.1) and Nanorana parkeri (XM_018553056.1) were obtained from GenBank. Sequencing and de novo assembly of the P. lessonae genome and de novo sequencing and assembly of three P. ridibundus transcriptomes were carried out by Dr. José Horacio Grau (Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, Dahlem Center for Genome Research and Medical Systems Biology, Berlin) and Dr. Albert J. Poustka (Dahlem Center for Genome Research and Medical Systems Biology Berlin, Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics, Berlin) in collaboration with Dr. Jörg Plötner (Museum für Naturkunde Berlin). The P. lessonae uqcrfs1 gene was obtained from a genome assembly with a N50 of 136,366 b constructed from seven next generation sequence libraries of different lengths assembled using the SOAPdenovo2_v2.04 genome assembler [18]. The reference sequence of Xenopus was blasted against the lessonae genome and transcriptome, and the ridibundus transcriptomes (RR1, RR2, and RR3) were deposited in a in-house database (https://blastserver.genomica-australis.de/) using tblastn [19]. Only high-quality scaffolds were selected and hits with an E-value of less than 0.05 were accepted as homologous sequences. ORF-finder (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder) was used to select the CDSs of the uqcrfs gene from each scaffold for both P. lessonae and P. ridibundus.

2.2. Alignment, Motif Search, and Basic Features of the uqcrfs1 Gene

Alignments of the 5’, 3’ and coding regions of the uqcrfs1 gene of P. lessonae, P. ridibundus, R. temporaria, N. parkeri, and X. tropicalis were performed in MEGA11 [20] using ClustalW [21] or Muscle [22] and manually improved. The MEME Motif Discovery tool [23] was used to find probable de novo motifs. The discovered motifs were submitted to the GOMo tool [24] to search all promoters to determine whether the motifs were significantly associated with genes, using the genome ontology to identify their biological roles. For each species, the length of the CDS, the length of the translated aa sequence, the GC content, and the GC content in the third position were determined.

2.3. Locality and Sample Selection for Genealogical Studies

To reveal the genealogical relationships of the exon2 fragment of the uqcrfs1 gene, 93 samples from 74 localities, mainly in Türkiye, were used based on the distribution of mitochondrial haplogroups (MHGs) [16]. The selection of samples was based on the spatial distribution patterns of each haplogroup, that is, the number of samples corresponded to the distribution areas of the haplogroups. Forty-four additional samples from Germany, Czech Republic, Italy, Spain, Greece, Cyprus, Tunisia, Jordan, and Kazakhstan were also included in the analysis (Supporting Information 1: Appendix S1). Total genomic DNA was isolated, as described by Akın et al. [15].

2.4. Genetic Analysis

A 441 bp fragment of exon2 (positions between 8 and 448 nucleotides) was amplified using the primer pairs (uq-F: TCCGTTCGCTTCTTACACAGC and uq-R: CCCAAGTGAGTGCAGACTCC) designed by Plötner et al. [11] and 5× FIREPol Master Mix (Solis Biodyne). The total reaction volume of 25 µL consisted of 1 µL genomic DNA, 1 µL primer (each forward and reverse), and 1× Master Mix (HOT FIREPol DNA polymerase, 5× blend master mix, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM dNTP, BSA, blue and yellow dyes) (Solis BioDyne). Amplification was performed under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 38 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 20 s, annealing at 58°C for 1 min, and elongation at 72°C for 4 min. A final extension was carried out at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR products were verified using 1.5% agarose gels. Sequencing reactions were carried out with the ABI terminator 3.1. Kit (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA, USA). To enhance the accuracy of the reads, particularly those derived from heterozygous positions, the PCR products were sequenced in both the forward and reverse directions. An ABI 3730x1 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) was used for electrophoresis and determination of fluorescently labeled nucleotides. All sequences were deposited in the EMBL Nucleotide Sequence Database under the accession numbers given in Supporting Information 1: Appendix S1.

2.5. Data Analysis

Uqcrfs1 sequences were aligned with CLUSTALW [21] using MEGA11 [20]. Heterozygous positions were checked in the chromatograms and corrected manually in the alignment if necessary. The allelic composition or allelic phasing of a genotype was determined on the basis of alleles obtained from homozygotes using PHASE 2.1 with default settings [25]. In addition, the selective neutrality of mutations in the uqcrfs1 sequences was assessed using Tajima’s D [26] and Fu’s Fs [27] as implemented in the program DnaSP v.6 [28]. Significant negative D and Fs values may indicate genetic hitchhiking, population growth, or background selection, whereas positive values may reflect balancing selection or secondary contact among previously isolated populations [27, 29, 30].

The genealogical relationships of the uqcrfs1 alleles were analyzed with Bayesian statistics using BEAST v1.10.4 and BEAUTI v1.10.4 [31]. Bayesian analysis was initiated from a random starting tree and based on the Hasegawa–Kishino–Yano (HKY) mutation model [32] with gamma-distributed site rate variation, and four discrete mutation classes (HKY+G). A strict clock was predicted using the Yule model as the tree prior. The MCMC was run for 100.000.000 steps and samples were taken every 10.000 steps to calculate posterior distribution parameters. As burn-in, the first recorded 1000 trees were discarded. In addition to Eastern Mediterranean frogs, uqcrfs1 sequences of additional water frog species were included in Bayesian analysis such as the European species Pelophylax perezi (Iberian Peninsula), Pelophylax bergeri (Apennine Peninsula), P. lessonae (Central Europe), Pelophylax shqipericus (western coast of the Balkan Peninsula), Pelophylax cretensis (Crete), and the Northwest African frogs of the Pelophylax saharicus group. The uqcrfs1 sequence of N. parkeri (XM_018553056.1) was used as the outgroup. In addition, uncorrected p distances between the different evolutionary water frog lineages were calculated using MEGA11. The uqcrfs1 topology and p distances were used to define allelic groups and subgroups.

3. Results

3.1. The Structure and Evolution of the uqcrfs1 Gene in Water Frogs

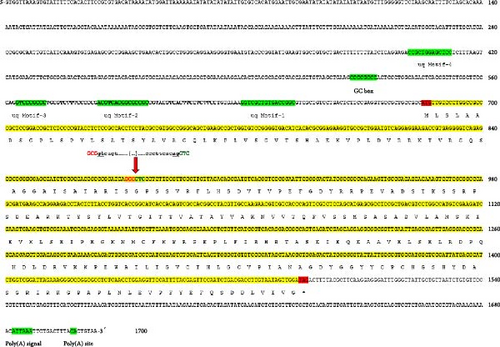

The uqcrfs1 gene of P. lessonae consists of two exons (exon1: 196 bp; exon2: 611 bp) and one intron of unknown length. The CDS is 807 bp long and the corresponding protein sequence comprises 268 aas. The 5’ region of the CDS does not contain a common TATA or CCAAAT box, but has several GC-rich blocks (Figure 1). The MEME motif discovery tool revealed that the 5’ coding region contains four undefined motifs (uq motifs 1–4) and a GC box (Figure 2). The GOMo gene ontology tool showed that motif-1 and motif-2 have transcription factor and RNA binding activities. Motif-1 is conserved in all species (X. tropicalis, R. temporaria, N. parkeri); motif-2 is conserved in P. lessonae and X. tropicalis except for two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Motif 3 is thought to function as a transcription factor; it is highly conserved, as indicated by only a single SNP between P. lessonae and X. tropicalis. Transcription factor activity is also inferred for motiv-4 which differs between X. tropicalis and P. lessonae in three SNPs. The GC box (GGGCGG) is identical to that of many other eukaryotic genes such as dihydrofolate reductase [DHFR [33] and epidermal growth factor receptor [34]. The 3’ region of the uqcrfs1 gene contains a polyA signal (AUUAAA), which is conserved except for a substitution in X. tropicalis. The polyA cleavage site is located about 12 nt downstream of the polyA signal (Figure 1).

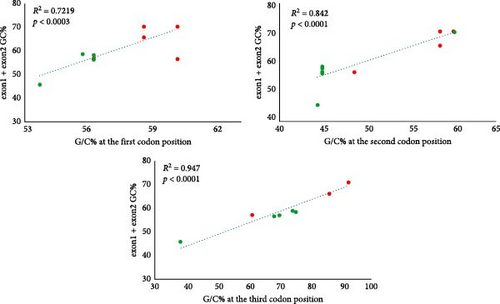

The basic characteristics of the uqcrfs1 gene obtained from different frog species revealed that the length of the CDS and its corresponding protein sequence are 807 nt (268 aa) in all species except X. tropicalis (822 nt; 273 aa); it has two exons in all species studied. Exon1 is 196 nt long in all species except X. tropicalis (211 nt) and exon2 comprises 611 nt in all analyzed species. The GC content of the CDS ranges between 48.4% (X. tropicalis) and 61.4% (R. temporaria). The G/C-ending codons of the CDS vary between 44.32% (X. tropicalis) and 79.48% (R. temporaria). The G/C-ending codons of exon1 range between 61.43% (X. tropicalis) and 92.31% (P. lessonae, P. ridibundus, and R. temporaria) and for exon2 between 38.42% (X. tropicalis) and 75.37% (R. temporaria) (Table 1). Remarkably, more than 90% of codons in exon1 end with G/C except in X. tropicalis (61.43%) while only more than 68% of codons in exon2 end with G/C, and it is very low in X. tropicalis (38%). Linear regression models revealed significant relationships between the GC content of the CDS and the G/C content at the first, second, and third codon positions (R2 = 0.7219, p < 0.0003 at the first codon; R2 = 0.842, p < 0.0001 at the second codon; R2 = 0.9473, p < 0.0001 at the third codon) (Figure 2).

| Species | CDSL (nt) | CDSL (aa) | GC (%) | G/C-ending codons (%) in exon (1 + 2) | Exon1 (nt) | G/C-ending codons (%) in exon1 | Exon2 (nt) | G/C-ending codons (%) in exon2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. lessonae | 807 | 268 | 59.9 | 75.37 | 196 | 92.31 | 611 | 69.95 |

| P. ridibundus (1) | 807 | 268 | 60.0 | 75.37 | 196 | 92.31 | 611 | 69.95 |

| P. ridibundus (2) | 807 | 268 | 59.6 | 74.25 | 196 | 92.31 | 611 | 68.47 |

| P. ridibundus (3) | 807 | 268 | 59.9 | 75.37 | 196 | 92.31 | 611 | 69.95 |

| N. parkeri | 807 | 268 | 59.9 | 77.24 | 196 | 86.15 | 611 | 74.38 |

| R. temporaria | 807 | 268 | 61.4 | 79.48 | 196 | 92.31 | 611 | 75.37 |

| X. tropicalis | 822 | 273 | 48.4 | 44.32 | 211 | 61.43 | 611 | 38.42 |

- Note: CDSL, length of the coding sequence.

- Abbreviations: aa, amino acid; nt, nucleotide.

Both the pn and pa distances for exon1 were zero between P. lessonae and P. ridibundus, while it ranged from 7.69% to 31.79% between P. lessonae and other frog species; the corresponding pa values ranged from 12.31% to 35.38%. The pn distance for exon2 between P. lessonae and P. ridibundus was 0.49%, while it ranged from 9.80% to 27.61% between P. lessonae and other species; the corresponding pa values showed values between 9.36% and 16.26%. The number of mutations between P. lessonae and the other species ranged from 0 to 36 in exon1, and from 0 to 110 in exon2 at the third codon positions (Table 2). Neutrality tests (Tajima’ s D and Fu’ Fs) for all uqcrfs1 exon2 sequences (n = 139 sequences for water frogs only), gave significant negative results (−191,987, p < 0.05) and −18.541, p < 0.001).

| Species | Divergence between P. lessonae—species (%) | Substitutions between P. lessonae—species (#) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exon1 | Exon2 | Exon1 + Exon2 | Exon1 (196–211 nt) | Exon2 (611 nt) | ||||||||||

| pnt | paa | pnt | paa | pnt | paa | First codon | Second codon | Third codon | Total | First codon | Second codon | Third codon | Total | |

| P. ridibundus (1) | 0 | 0 | 0.49 ± 0.19 | 0 | 0.37 ± 0.15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| P. ridibundus (2) | ||||||||||||||

| P. ridibundus (3) | ||||||||||||||

| R. temporaria | 7.69 ± 1.94 | 12.31 ± 4.02 | 9.80 ± 1.09 | 9.36 ± 2.04 | 9.29 ± 0.95 | 10.07 ± 1.78 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 15 | 12 | 4 | 35 | 51 |

| N. parkeri | 21.03 ± 2.76 | 26.15 ± 5.55 | 11.93 ± 1.23 | 10.84 ± 2.16 | 14.13 ± 1.14 | 14.55 ± 2.10 | 10 | 8 | 20 | 38 | 12 | 12 | 40 | 64 |

| X. tropicalis | 31.79 ± 3.08 | 35.38 ± 5.94 | 27.61 ± 1.64 | 16.26 ± 2.53 | 28.62 ± 1.51 | 20.90 ± 2.39 | 16 | 9 | 36 | 61 | 27 | 14 | 110 | 151 |

- Note: Mutations between P. lessonae and the other species at the first, second, and third positions for each exon were indicated.

3.2. Genealogical Relationships of Eastern Mediterranean Water Frogs

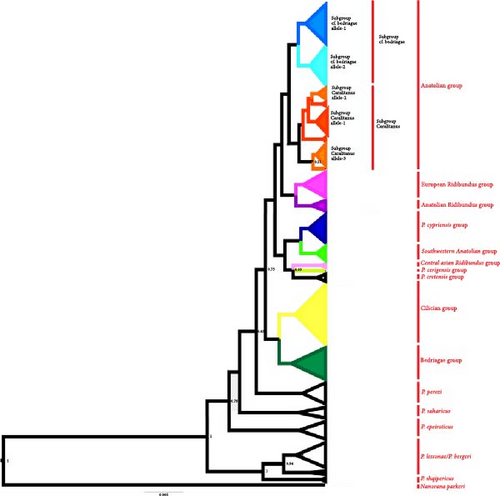

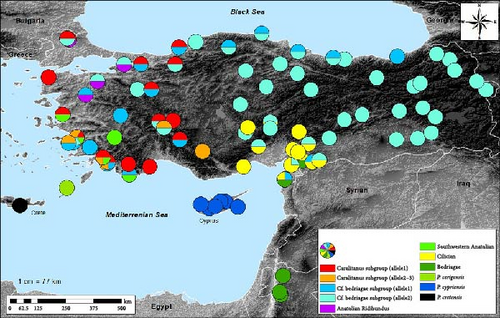

The Bayesian tree topology (Figure 3 and Supporting Information 3: Appendix S3) and uncorrected p distances calculated from a 441 bp fragment of exon2 (Supporting Information 2: Appendix S2) indicated the existence of 10 uqcrfs1 allelic groups in Eastern Mediterranean water frogs (Figure 4). The mean p distances between these groups ranged from 0.005 (P. cypriensis group—P. cretensis group) to 0.018 (P. cerigensis group—Southwestern Anatolia/Bedriagae/Anatolian Ridibundus groups), while the mean distance values within each group were ≤0.004.

The Anatolian group is the most widespread, being found in almost all of Anatolia and in the Thrace region, with the exception of the Çukurova plain. It consists of two subgroups (Caralitanus and cf. bedriagae), with a mean distance value of 0.004 between them. The Caralitanus subgroup includes a widespread allele, car uq allele-1, which occurs throughout Western to Central Anatolia and Thrace, and two locally distributed alleles, car uq allele-2 (in the Lake District region and in Southwestern Anatolia) and car uq allele-3 (in Southwestern Anatolia) (Figure 4).

To date, only two alleles have been identified within the cf. bedriagae subgroup. The cf.bed uq allele-1 was found throughout Western and Central Anatolia as well as in the vicinity of the Black Sea, while the cf.bed uq allele-2 was found in almost all areas of Anatolia and in Thrace. As the name suggests, the Southwest Anatolian Group is geographically restricted to Southwestern Anatolia, where it is characterized by the allele southwestern uq allele-1. Heterozygous individuals exhibiting alleles characteristic of the Anatolian and the Southwestern Anatolian groups, or different Anatolian subgroups, were found in numerous localities across their distribution ranges.

The European Ridibundus group includes four ridibundus-specific alleles (rid uq allele1–4) and one kurtmuelleri-specific allele (kur uq allele-1). Alleles of this group were found in Western Anatolia and Thrace, together with the Anatolian alleles rid1–3. The Central Asian Ridibundus group was found in Kazakhstan (asian rid uq allele-1). Heterozygous individuals combining alleles of the Anatolian Ridibundus group and the Anatolian subgroups have been found in both Western Anatolian and Thracian populations.

The Cilician group, comprising five alleles (cil uq allele1-5), was found in the Cilician and Narlı plains in both the western and eastern directions of the Amanos Mountains; this group is distributed as far as Kayseri Sultansazlığı in Türkiye. In some population, individuals were heterozygous for both the cf.bed uq-2 allele and one of the cil uq alleles. The Bedriagae group, genealogically the closest group to the Cilician group, consisted of three bedriagae alleles (bed uq allele1–3). It was found in Jordanian populations and in the provinces of Kilis and Hatay, where individuals were either heterozygous for the cf. bed uq allele-2 or one of the cil uq alleles. The last three groups P. cerigensis, P. cypriensis, and P. cretensis were exclusively found on Karpathos, Cyprus, and Crete, respectively.

4. Discussion

4.1. Structure and Evolution of P. lessonae uqcrfs1 Gene

A comparative analysis of 20 respiratory and 160 gametogenic genes from multiple transcriptomes of one P. lessonae (LL) and three P. ridibundus (RR) individuals revealed that compared to the gametogenic genes, the mean GC content of the respiratory genes was significantly higher in P. lessonae (50.6% ± 5.5%) and in P. ridibundus (51.1% ± 5.4%) than the GC content of the gametogenic genes in P. lessonae ( = 46.1% ± 4.6%) and P. ridibundus ( = 45.9% ± 4.5%) [10]. In addition, while the GC content of respiratory genes in Pelophylax spp. ( = 50.8% ± 5.42%) was significantly higher than in X. tropicalis ( = 48.2% ± 4.16%), the GC content of the gametogenic genes in Pelophylax spp. ( = 46.0% ± 4.5%) was not significantly different from that observed in X. tropicalis ( = 45.9% ± 5.3%) [10]. This corroborates the findings that the mean GC content of the respiratory gene uqcrfs1 is elevated not only in P. ridibundus and P. lessonae but also in N. parkeri and R. temporaria (>59%) in comparison to X. tropicalis. In addition, the results revealed that the GC content of all codon positions was significantly correlated with the overall GC content of both exons. However, the third codon position exhibited the strongest contribution to this correlation. In accordance with this, the uqcrfs1 gene of X. tropicalis, which exhibited a GC content of only 48.4%, had also a rather low frequency of G/C-ending codons (44.32%). Conversely, all species with higher GC contents exhibited a higher frequency of G/C-ending codons (74%). It has recently been indicated [35] that although vertebrates have GC-poor genomes (37%–46%) but they have much higher G/C ending codons (56%–64%) than genomes. Furthermore, even in particular genomic regions of mammals and birds with the highest GC content, the overall GC content is lower than that of G/C-ending codons [36]. The GC content and the number of G/C-ending codons are subjected to different regulatory processes. The former indicates only the nucleotide substitutions, whereas the latter reflects a dynamic interaction between substitutions, movement of mobile elements, and deletions [37]. The high GC content has been demonstrated to play several different roles in the gene expression. For instance, it has been shown that CpG-rich promoters are capable of activating transcription by means of recruiting specific transcription factors [38]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the high GC content at the 5’ end of CDSs of genes (particularly the first half of CDS (nt 1–360) in the human genome has a significant impact on efficient gene expression. The studies demonstrated that elevated levels of GC content were associated with increased protein yield, mRNA yield, mRNA nuclear export, cytoplasmic mRNA localization, and translation of unspliced reporters [39–41].

Among the species studied, X. tropicalis is the only species with short generation in tropical and subtropical zones of West Africa, compared to the other species found in temperate zones (R. temporaria and P. lessonae in Europe; P. ridibundus in Europe and Western Asia; and N. parkeri in Tibet and Nepal). Therefore, the observed low GC content in X. tropicalis may be due to a species-specific codon usage bias (CUB). The study on CUB in X. leavis indicated that the mean frequency of G/C-ending codons in nuclear genes is 48.8%, with only 19% of all investigated genes in the Xenopus genome exhibiting a value greater than 60% for G/C-ending codons. It was revealed that T-ending codons are statistically more prevalent among highly expressed genes [42]. It can therefore be posited that this CUB is a consequence of natural selection acting on the efficiency of translation speed. In other words, highly expressed genes (particularly housekeeping) use codons that correspond with the most readily available tRNAs, thereby ensuring that these genes are translated at a high rate. Translational selection thus affects the usage of specific codons, resulting in a low GC content in highly expressed genes. This low GC content observed in the X. laevis genome [42, 43] was also found in the uqcrfs1 gene of X. tropicalis in this study. Thus, the uqcrfs1 gene of X. tropicalis could be differentially regulated to compensate respiratory needs of the species to adapt to its tropical environment, characterized by elevated temperature and a short generation time. This adaptation can be facilitated by species-specific CUB and the low GC content. Recently, it was found that genes having a higher frequency of A/T ending codons are expressed more coordinately and are more likely to be part of the same protein complex [44]. However, the interplay between selection, mutation, genetic drift, recombination [45, 46], and recently proposed GC-biased gene conversion, which prefers GC over AT alleles during meiotic recombination [37, 47, 48], which also have a significant influence on the shaping of GC-content in genomes.

The results of the comparative sequence analysis demonstrate that exon1 is highly conserved, whereas exon2 exhibits considerable variability. This is evident not only between P. lessonae and P. ridibundus but also within both different water frog species and closely related evolutionary water frog lineages, as supported by the genealogical tree. However, both exon1 and exon2 are similarly variable between P. lessoane and R. temporaria, Nano parkeri and X. tropicalis. In addition, the results of the neutrality tests in different water frog species and lineages indicate that exon2 is not evolving neutrally. This could be attributed to genetic hitchhiking [49], whereby exon1, which encodes the mitochondrial targeting protein, may have been strongly selected in conjunction with nearby polymorphic regions (exon2). It seems that mutations at the third position of exon2 can be tolerated since they only alter codons without changing aas in the Rieske domain. Recently, it has been suggested [50] that CUB (preference A/T versus G/C at wobble positions) is strongly positively correlated with relative mRNA level and protein abundance so directly affects gene expression level by providing suitable CDSs to the machinery of transcription and translation. This observed high variability in the uqcrfs1 gene can be explained by mitonuclear coevolution [51, 52], which suggests that it works with nuclear compensation. This is due to the fact that mitochondrial genomes accumulate slightly deleterious mutations at a higher rate than nuclear genomes. This is a consequence of uniparental inheritance, small effective population size, and lack of recombination [53, 54]. Thus, deleterious mitochondrial mutations should force compensatory changes in nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins in order to sustain efficient mitonuclear coadaptation and functional mitochondria [55, 56]. Then, nuclear-encoded genes and mitochondrial genes may show correlations in their evolutionary rates compared to the other nuclear genes, as suggested by Weaver et al. [57] thus, the nuclear genes that interact with mitochondrial genes, evolve faster than other genes. It can therefore be concluded that alleles of exon2 belonging to the lineage-specific allelic group correspond to the mitochondrial group of this lineage, such as the Cilician allele group and the Cilician main haplogroup. This demonstrates the lineage specificity of these alleles.

In contrast to variable exon2, 5’ region, and 3’UTR contain several conserved functional motifs. Since the 5’ region of the uqcrfs1 gene lacks a clear TATA box but contains four GC-rich dispersed motifs (1–4), and a GC box, it resembles the core promoter type of widely expressed housekeeping genes that show dispersed transcription initiation [58, 59]. It has been shown that the human uqcrfs1 gene also lacks a TATA box, only a GC box is present [9], which is a binding site for the transcription factor SP1, which is important for transcription initiation and efficient transcription in the TATA-less promoters [60, 61]. Thus, these four dispersed motifs and the GC box could be probably involved in transcriptional regulation (transcription initiation and efficient transcription) of the uqcrfs1 gene in P. lessonae. The PolyA signal (AUUAAA) identified in this study was found to be one of the most common variants after the AAUAAA variant for human genes [62]. However, the function of the five motifs in the 5’ region and the polyA signal in the 3′ region of the gene should be tested experimentally.

4.2. Implications for Water Frog Systematics

Although some nodes in the uqcrfs1 topology were supported by only low posterior probability values (<70), probably because of the rather short length of sequence analyzed, the results of Bayesian analysis correspond well with systematic and phylogenetic hypotheses based on mitochondrial and nuclear genes [14–16]. For example, there is a clear separation of the Cilician clade from the other Anatolian lineages, which represent three distinct sublineages, namely the caralitanus lineage, the cf. bedriagae lineage, and the ridibundus lineage. Similar to the SAI-1+RanaCR1 gene tree given by Akın Pekşen [16], both the Anatolian subgroups (Caralitanus and cf. bedriagae) have locally (e.g., Lake District region and Southwestern Anatolia) and widely distributed alleles, but there are also differences in the allele distribution between the two nuclear markers [16]. In contrast to the gene tree based on the SAI-1 marker, the Southwestern Anatolian group is well separated from the main Anatolian group in the uqcrfs1 gene tree and forms a distinct group rather than becoming a subgroup within the Anatolian group [16].

Moreover, as in the SAI-1 gene tree, ridibundus alleles formed three groups (European, Anatolian, and Central) which are restricted to specific regions in Türkiye. However, the restricted sample size precludes the verification of region-specific distribution of ridibundus alleles. In the uqcrfs1 gene tree, P. cerigensis from Karpathos formed a separate group, which is closer related to P. cypriensis (Cyprus) and P. cretensis (Crete) than the Anatolian clade as in the nuclear SAI-1+RanaCR1 trees [16, 63] and the mitochondrial gene trees [14, 15]. In addition, P. cypriensis and P. cretensis seem to be closely related to Anatolian frogs as in the SAI-1+RanaCR1 gene tree [16].

According to uqcrfs1 gene tree, the Cilician and Bedriagae groups are sister groups, but, in the SAI-1+RanaCR1 tree, the Bedriagae group is closely related to the lessonae group (P. shqipericus, P. lessonae, and P. bergeri). Moreover, as with SAI1+RanaCR1 gene [16], heterozygous individuals were identified with alleles characteristic of the Cilician and Bedriagae groups. In order to verify the relationship between these two groups, detailed sampling is required throughout the catchment of the River Orontes in the region between Hatay in Türkiye and Jordan.

In accordance with the SAI-1+RanaCR1 and mtDNA trees, the uqcrfs1 gene tree supports the monophyly of P. shqipericus, the P. bergeri/P.lessonae group, P. saharicus, P. perezi, and P. epeiroticus. However, in contrast to previous results, it does not place P. saharicus and P. perezi as basal groups and does not support their sister-group relationships, although they still form two closely related groups [14–16]. While the position of some allelic groups and the number of subgroups in the uqcrfs1 gene tree are somewhat different, it largely supports the results of previous nuclear and mitochondrial genealogical studies. Thus, uqcrfs1 is a useful marker to identify not only the geographical origin of species and lineages but also their hybrids which was previously demonstrated by Tecker et al. [12] and Krage et al. [13].

5. Conclusion

In summary, the data presented here provide new insights into the structure and evolution of the uqcrfs1 gene of P. lessonae. Furthermore, the utility of exon2 sequences as a polymorphic nuclear marker was demonstrated, corroborating previous hypotheses on water frog systematics (e.g., Plötner et al. [14], Akın et al. [15], and Akın Pekşen [16]). Further comparative structural studies of the uqcrfs1 gene and its encoded protein, including different water frog species, may provide new insights into the fine-scale evolution and physiological function of this gene, which may be relevant of general relevance.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study was funded partially by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (grant PL 213/3-1, 3-2, 3-3).

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Dr. Jörg Plötner for his valuable detailed comments and suggestions on the manuscript. I also thank Dr. Banu Kaya Özdemirel for preparation of the locality map and to Diyar Hamidi for contribution to Bioinformatics analysis. Tissue samples were kindly provided by Jörg Plötner (Germany, Montenegro, Tunis, France), Lukas Choleva (Czech Republic), Hansjürg Hotz (Greece, Italy, Spain, Algeria), Felix Baier (Cyprus), Glib Mazepa (Jordan), and Spartak Litvinchuk (Kazakhstan). I am especially grateful to Jörg Plötner who kindly provided sequences of DNA samples mentioned above. I would like to thank Robert Schreiber for technical assistance. This research was funded partially by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (grant PL 213/3-1, 3-2, 3-3).

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Genomic sequences derived in this study were submitted to the GenBank database and given the accession numbers between LN794250-LN794264 and PV275573-PV275573.