Group Relative Deprivation and Violent Radicalism: Moving Toward a Comprehensive Model

Abstract

Many terrorist attacks, carried out in the name of Islam, have posed significant threats to human lives across the globe. Research aiming to understand the roots of radicalism has identified Group Relative Deprivation (GRD) as a central explanatory concept. The present research (Study 1, N = 209; Study 2, N = 611; Study 3, N = 638) conducted in France, home to Western Europe’s largest Muslim community, failed to confirm the role of GRD in explaining variations in radicalism. Earlier research showed that GRD predicts activism and that activism is positively correlated with radicalism. Consequently, we hypothesized and found that group membership (Muslims vs. non-Muslims) is related to activism (not radicalism), that GRD mediates this relation between group membership and activism, and that GRD is predictive of radicalism only indirectly, via activism. The results also confirm that group-based contempt is uniquely predictive of support for violence, unlike group-based anger. The theoretical, methodological, and policy implications of these findings are discussed.

Group violence ordinarily grows out of collective actions that are not necessarily violent

Oberschall, 1978, p. 302

1. Introduction

Islamist terror attacks have threatened both democratic and nondemocratic states around the world [1]. Research in social psychology has contributed in unprecedented ways in the effort to better understand the roots of Islamist radicalism [2, 3]. The present research examines whether Muslims living in the West are more likely than others to support political violence and revisits one of the most important psychological explanations of radicalism based on the theory of relative deprivation.

1.1. Relative Deprivation and Violent Radicalism

Relative deprivation theory has a long history in psychology and related fields, guiding research on protest movements, riots, rebellions, and even political revolutions for over 5 decades [4–9]. The first important distinction to consider in this area of research is that between Individual (or egoistical) Relative Deprivation, when the individual perceives that he or she is worse-off than others, and Group (or fraternal) Relative Deprivation, when the individual perceives that an ingroup is worse-off than an outgroup [10–12]. Research has shown that Individual Relative Deprivation is associated with individualistic outcomes (i.e., self-improvement strategies), whereas Group Relative Deprivation (GRD) is better-suited to explain group or collective outcomes [13]. Research has also studied relative deprivation on behalf of others (see [14]), and studies have been conducted among majority group members, not only among minorities [15, 16].

As explained below, GRD can be defined in terms of two dimensions or components: the cognitive component, a perceived inequality between two groups, and an affective component, the feelings of discontent, anger, or resentment associated with this perceived discrepancy [17]. The present research is concerned with the fact that, in recent years, an increasing number of studies have suggested that GRD is a basic factor in the explanation of Islamist radicalization in Western countries [18–23]. For example, concerning the radicalization of Muslim youth in Europe, Verkuyten [22] suggested that “Radicalization would be the result of a collective discontent caused by a sense of relative deprivation” (p. 25). In his book Why people radicalize, van den Bos [24] argued that relative deprivation and perception of unfairness are “pivotal antecedents of enhanced radicalization” (p. 12). Similarly, Obaidi et al. [20] suggested that educated Western Muslims compare their status with those of similarly educated non-Muslims and that GRD is “a key factor in explaining Western-born Muslims’ endorsement of extremism” (p. 1).

In the present research, we challenge such claims and propose an alternative, more Comprehensive Model of the role of GRD in violent Radicalism (COMRAD). In three studies, we attempt to replicate past research on the link between GRD and support for political violence, following as closely as possible the cross-sectional method used in previous studies (e.g., [20]). Our analysis reveals that such empirical tests yield deceptive results when the crucial differentiation between activism and radicalism is overlooked.

The distinction between normative and non-normative collective actions is well established [9, 25–27]. Normative collective actions (or activism) are peaceful demonstrations that follow dominant democratic societal norms whereas non-normative collective actions (or radicalism) are breaking away from these norms with the use of illegal and/or violent tactics [28]. Importantly, research has shown that there are significant positive correlations between measures of support for activism and radicalism [25, 28, 29]. Moreover, the bulk of past research has shown that GRD is strongly predictive of support for, or participation in, normative collective actions (for meta-analyses, see [13, 30]; for recent empirical studies, see [31–34]). A fundamental question arises, currently without definitive answers, regarding whether the observed correlations between GRD and radicalism might be spuriously influenced by their association with a third factor: nonviolent activism. This pivotal inquiry forms the basis of our investigative series. Specifically, Study 1 served as an exploratory phase, prompting the development of a more comprehensive model of GRD’s role. This model was then rigorously tested in Studies 2 and 3.

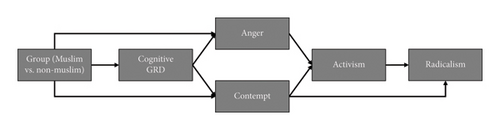

We examine the relations between GRD and support for Islamist political violence by controlling for support for normative action on behalf of Muslims. We argue that GRD will first predict support for normative collective actions that will, in turn, predict support for non-normative actions, in a stage-like process. In line with our rationale, Moghaddam [3, 35] has presented a dynamic model of intergroup coradicalization in which GRD is important early at the beginning of group mobilization. We suggest that when people feel GRD, they do not suddenly become violent. They become oriented to support group action. Positing a direct link between GRD and violence is akin to the “frustration-aggression” hypothesis that was translated into “relative deprivation-political violence” by Gurr [8] and was deemed empirically and theoretically untenable several decades ago [2, 10, 36], and even by Gurr [8] himself (see [37]). More recently, evidence from Fodeman, Snook, Horgan [29] investigating converts to Islam led them to argue that “participation in nonviolent behaviors facilitates participation in violent ones” (p. 694). Consistent with the opening quote from Oberschall [38], this suggests that, as a general rule, involvement in normative actions occurs first and is followed by non-normative actions. Indeed, a major publication by Louis et al. [39] has demonstrated, in a series of nine experiments and one simulation conducted in the context of various social movements, that when normative collective actions are failing, the effect is to radicalize the subsequent tactical choices. Consistent with our reasoning, this suggests that regardless of any feelings of GRD, the political response that a social movement gets can orient subsequent actions. In other words, the transition from normative to non-normative collective actions can be explained without a need to postulate the role of GRD. Thus, we hypothesize that GRD predicts support for activism which, in turn, will fully mediate the link between GRD and support for political violence (see Figure 1).

The proposed model is informed by major theoretical works conducted to understand why people turn to political violence. In his influential staircase model of terrorism, Moghaddam [35] suggests that to understand why people engage in terrorist or violent actions, one needs to understand the different steps that people go through before they reach the final one. He specifically argues that even when people experience deep feelings of relative deprivation, most of them remain on the ground floor, and they do not generally become violent. We add that at this stage, they will be motivated to engage in nonviolent collective actions, consistent with the bulk of past research showing a link between GRD and collective action (e.g., [30, 40]). Over the course of this period of activism, many activists will turn to more radical actions, especially if their movement fails [39], or if they are the victim of repression [1]. On the basis of an historical analysis of terrorism and revolutionary movements across the globe, this is one of the key points noted by Sageman [1]. He writes “One of the findings of the empirical chapters is that politically violent actors often did not view themselves [as such]. Many were students, workers, or citizens with some sort of grievance whose peaceful demonstration was violently repressed by the state” [1], p. 17. This is directly suggesting that a period of nonviolent activism can lead to radicalism. For this reason, we do not consider normative and non-normative actions on an equal footing as dependent variables, as assumed, for example, by Tausch et al. [26].

Considering previous research on GRD, it is also important to distinguish between cognitive and affective components of this phenomenon [41]. The variable labeled “group-based relative deprivation” by Obaidi et al. [20] can be assumed to represent in fact the cognitive component; its effect on activism is mediated by intergroup emotions [42], the affective component of GRD [30, 32, 43]. The cognitive component of GRD is the perception that the ingroup is deprived relative to the outgroup [17]. The affective component of GRD is the psychological reaction to such a discrepancy, usually measured as anger or resentment [13, 20]. Thus, as shown in Figure 1, our theoretical model includes these mediated links between group membership, GRD (cognitive component), group-based anger (affective component), activism, and radicalism.

It is imperative to be clear about the intergroup emotions that are associated with radical group behaviors because this can have significant policy implications. Existing research reveals a conflicting picture in this regard (for a review, see [44]). For example, many studies suggest that anger predicts support for non-normative or violent actions [19, 20]. Across six studies using cross-sectional data, Obaidi et al. [20] report that group-based anger predicts support for political violence among Western-born Muslims. Matsumoto, Frank, and Hwang [45] argue that anger, contempt, and disgust, together, are the main emotions predicting political violence. However, these studies do not consider whether anger differentially predicts normative as opposed to non-normative actions. This was the aim of research conducted by Tausch et al. [26] who showed in three studies that when group-based contempt is measured alongside group-based anger, contempt emerges as the main predictor of radical group behavior, not anger (see also [46]). In order to contribute to this debate, we have also integrated measures of group-based contempt alongside anger in three studies.

Jost et al. [47] have replicated the results of Tausch et al. [26], suggesting that anger predicts primarily nonviolent action or activism rather than violent radicalism. Integrating these findings related to anger and contempt within a relative deprivation framework, we propose that, as with other intergroup emotions, the origin of group-based contempt can be attributed in part to cognitive GRD (see Figure 1).

1.2. The Present Research

Islamist terror attacks have struck numerous capital cities in Europe and North America, leading to the belief that Islam is inherently violent and that Muslims are more extremists than non-Muslims. The association between “Muslim” and “terrorism” has become virtually automatic, as illustrated recently by Arnoult et al. [48]. However, there are surprisingly little systematic attempts at setting the record straight empirically regarding this popular belief linking Muslims with greater radicalism. In psychology, studies are often conducted on Muslim samples only (e.g., [49, 50]), preventing by design any answer to the question of whether Muslims, as a group, are more radical than non-Muslims. Given that Islamist terror attacks in Europe and the United States have often been orchestrated by Muslims born and raised in Western societies (King & Taylor, 2011), it would appear critical to know if nowadays, Muslims in Europe are indeed on a radical path. Evidence of widespread prejudice and anti-Muslim discrimination documented in government reports and academic research alike [51] furnishes a strong basis for the development of a collective response. Consequently, in order to fill this gap, the current research affords systematic comparisons of Muslim and non-Muslim samples in France regarding their level of support for normative (activism) and non-normative actions (violent radicalism). We expect that support for activism will be correlated positively with support for radical actions. Moreover, consistent with COMRAD, we predict that Muslims will be more supportive of normative actions than non-Muslims and that this effect will be mediated by the cognitive and affective components of GRD. Furthermore, we predict that only group-based contempt will have a direct link with radicalism and that group-based anger, the traditional component of GRD, will be indirectly predictive of radicalism via activism.

2. Method

All the data backing up the present research, as well as relevant supporting analyses and tables, can be openly accessed through the OSF project page at https://osf.io/6hvku/?view_only=1adafd29b1bc4dcfb174e8bedc278fd77.

2.1. Participants

As part of a broader project dealing with group polarization and the effects of national policies on the willingness to use political violence, we recruited participants in France who indicated to be Muslims or not in response to an online questionnaire. All participants, Muslims and non-Muslims, answered the same questionnaire requesting their personal views, their attitudes, and their feelings about issues of inequality between Muslims and others in France. Pilot testing and extensive evaluations by the ethical review board led to the development of the final questionnaire. In Study 1 conducted in January 2020, a total of 212 participants were recruited through an invitation to participate posted on Facebook, with 41 Muslims (20%). Three participants were excluded because they were not 18 years old or older leaving a total of 209 participants. In Study 2 and Study 3, we commissioned a marketing firm to recruit 600 French participants, half of them being Muslims. Study 2 was conducted in July 2021 with 611 participants (307 Muslims). Study 3 was conducted in July 2022 with 638 participants (320 Muslims). Thus, except for Study 1, the samples include an approximately equal number of Muslims and non-Muslims. Also, except for Study 1, the samples include a rich mix of participants in terms of age, gender, or occupation. In addition, Paris and all major regions in France are covered (see online Supporting Information, Tables S2–S4 for further details on the participants, https://osf.io/pba64?view_only=1adafd29b1bc4dcfb174e8bedc278fd7). For a discussion of sample size and sensitivity analyses, as well as the full description of all measures used for all studies (Table S1), please see Supporting Information.

2.2. Measures

After filling out a consent form, the participants were instructed to answer an online questionnaire (in French) including the following measures using a five-point scale response format (1 = Strongly Disagree; 5 = Strongly Agree):

2.2.1. GRD (Cognitive Component)

In Study 1 and Study 2, a two-item scale was computed to measure this variable using items from Obaidi et al. [20] adapted to the French context: (“Muslims will always be at the bottom of the social ladder and non-Muslims French people at the top”; “I do not think that Muslims are oppressed in France” [reverse scored]). With the latter item reverse-coded, these two items are significantly and positively correlated in Study 1, r (209) = 0.17, p = 0.010, and in Study 2, r (611) = 0.26, p = 0.001. In Study 3, we added three new items, adapted from previous research, to improve our measure of this cognitive component of GRD. This five-item scale was reliable (alpha = 0.75, see Table S5).

2.2.2. Group-Based Anger

Adapted from Tausch et al. [26] and Obaidi et al. [20], a three-item scale was used to measure group-based anger, the affective component of GRD (e.g., “When I think of the fact that Muslims have a disadvantaged status, this makes me angry”). This scale proved reliable in each study (alpha = 0.75, 0.80, and 0.83, respectively).

2.2.3. Group-Based Contempt

Adapted from Tausch et al. [26], Study 1 and Study 2 used a two-item scale to measure group-based contempt (“When I hear certain negative comments about Muslims, I feel despised”; “The foreign policy of France in Muslim countries can be perceived as expressing contempt toward Muslims”). These two items are significantly and positively correlated in Study 1, r (209) = 0.20, p = 0.003, and in Study 2, r (611) = 0.37, p = 0.001. In Study 3, we added a third item (“I have the impression that French Muslims are totally despised by non-Muslims”) to form a three-item scale of group-based contempt (alpha = 0.71).

2.2.4. Support for Normative Collective Actions (NA) on Behalf of Muslims

Adapted from previous research [20, 26, 28, 49], three items were used to measure support for nonviolent (or normative) collective actions (“One should be ready to take part in peaceful protest in support of minorities such as Muslims”; “I support political actions taken to improve the life of Muslims”; and “French Muslims should help their oppressed brothers and sisters in other parts of the world through dialogue and sensitization”). This scale proved reliable in each study (alpha = 0.65, 0.66, and 0.71 respectively).

2.2.5. Support for Non-Normative Collective Actions (NNA) on Behalf of Muslims

Similarly, three items were used to measure this variable (“In general, I am supportive of Muslim groups who often resort to violence,” “Muslims in France should help their oppressed brothers and sisters in other parts of the world through every means possible,” and “As Muslims, one should be ready to do everything for the cause of Muslims”). Reliability estimates for this three-item scale were 0.62, 0.67, and 0.62, respectively. Principal component factor analysis showed that items purported to measure support for NA loaded on a separate factor from items purported to measure support for NNA, confirming construct validity (see Table S6). One exception was in Study 3 with one item expected to measure NNA that loaded equally on both factors (the third item listed above). This item was dropped from the measure of support for NNA in Study 3.

As expected based on previous research, scores on the measure of support for NA correlated significantly and positively with support for NNA in Study 1 (r = 0.32, p = 0.001, N = 209), in Study 2 (r = 0.36, p = 0.001, N = 609), and in Study 3 (r = 0.37, p = 0.001, N = 636). The more participants support normative collective actions, the more they also support non-normative collective actions. Response to a separate item measured in each study (“I condemn violence perpetrated by certain Muslim groups”) was used as a criterion to assess the discriminant validity of the two scales. As expected, the measure of support for NA correlated significantly and positively with this item in all three studies (r = 0.15, 0.17, and 0.27 respectively), confirming that this scale assess support for nonviolent actions. In contrast, the measure of support for NNA correlated significantly and negatively with this item in all three studies (r = −0.19, −0.22, −0.31, respectively), confirming that this scale assesses support for violent actions.

Finally, in Study 3, measures of activism and radicalism developed by Moskalenko and McCauley ([25]; Study 3) were added to complement the other measures of support for NA and NNA described above. These measures are more general in that participants are first asked to identify a group that is important to them and then to answer a series of questions with this group in mind. Thus, in Study 3, the validity of COMRAD will also be tested using these three-item measures of activism and radicalism developed by Moskalenko and McCauley ([25]; Study 3).

2.2.6. Activism

For this measure of activism, the three items are “I would volunteer my time working (i.e. write petitions, distribute flyers, recruit people, etc.) for an organization that fights for my group’s political and legal rights”; “I would join/belong to an organization that fights for my group’s political and legal rights”; and “I would donate money to an organization that fights for my group’s political and legal rights”). The reliability was 0.88.

2.2.7. Radicalism

For this measure of radicalism, the three items are “I would continue to support an organization that fights for my group’s political and legal rights even if the organization sometimes break the law”; “I would continue to support an organization that fights for my group’s political and legal rights even if the organization sometimes resorts to violence”; and “I would attack police or security forces if I saw them beating members of my group.” The reliability was 0.82. Consistent with Moskalenko and McCauley [25], activism items loaded on a separate factor from radicalism items (see Table S7).

As noted above for the measures of support for NA and NNA, there is a significant and positive correlation between the scale of activism and that of radicalism, r (638) = 0.50, p = 0.001. This strongly confirms the need to control for activism when testing the effects of other variables on radicalism. In support of the discriminant validity of these measures, those scoring high on the activism scale are agreeing that “I condemn violence perpetrated by certain Muslim groups” (partial r = 0.19, p = 0.001) but those scoring high on the radicalism scale are not (partial r = −0.30, p = 0.001). Also supporting the validity of the scale of activism and radicalism used in the present study, we find that scores on the scale of activism correlate significantly and positively with our measures of support for normative actions described above (r = 0.40, p = 0.001) but not with our measure of support for non-normative actions (partial r = 0.06, ns, with the level of support for normative actions controlled).

Similarly, scores on the scale of radicalism correlate significantly and positively with our measures of support for non-normative actions (r = 0.43, p = 0.001) but not with our measure of support for normative actions (partial r = 0.01, ns, with the level of support for non-normative actions controlled). Thus, the activism scale measures indeed the level of support for peaceful collective actions, whereas the radicalism scale measures the level of support for more radical and potentially violent actions.

All participants volunteered to take part and were thoroughly debriefed at the end of the study. In Studies 2 and 3, beside questions on demographic information that always appeared first, all measures were presented in a random order for each participant.

3. Results

The results are presented in three main parts. In the first two sections, the statistical effects of group membership (Muslims vs. non-Muslims) on support for NA and support for NNA, respectively, are examined. In the remaining section, we use structural equation modeling to test the extent to which our model displayed in Figure 1 has a good fit with the observations and can explain the statistical effect of group membership.

3.1. Are Muslims More Supportive of Normative (Nonviolent) Actions?

Table 1 presents the mean scores of Muslims and non-Muslims on our scale of support for NA observed in each study. Tests of significance, controlling for age, gender, and support for NNA, indicate in each study that Muslims are more supportive of normative actions than non-Muslims, with an effect size that is moderate in magnitude (see Table 2). Similarly, when using the activism scale of Moskalenko and McCauley [25] in Study 3, the results indicate a significantly higher level of activism among Muslims (Table 1), regardless of the level of support for radicalism (see Table 3).

| Study 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muslims | Non-Muslims | t | p | d | |||

| N = 41 | N = 171 | ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Support for normative action | 4.09 | 0.85 | 3.46 | 0.90 | 4.07 | < 0.001 | 0.71 |

| Support for non-normative action | 2.50 | 0.89 | 2.25 | 0.81 | 1.76 | 0.080 | 0.31 |

| Study 2 | |||||||

| Muslims | Non-Muslims | t | p | d | |||

| N = 307 | N = 304 | ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Support for normative action | 3.58 | 0.84 | 2.93 | 0.80 | 9.81 | < 0.001 | 0.79 |

| Support for non-normative action | 2.70 | 0.81 | 2.35 | 0.94 | 4.89 | < 0.001 | 0.39 |

| Study 3 | |||||||

| Muslims | Non-Muslims | t | p | d | |||

| N = 320 | N = 318 | ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Support for normative action | 3.66 | 0.80 | 2.93 | 0.84 | 11.29 | < 0.001 | 0.89 |

| Support for non-normative action | 2.50 | 1.01 | 2.18 | 0.80 | 4.53 | < 0.001 | 0.35 |

| Support for activism | 3.06 | 1.05 | 2.80 | 1.11 | 3.01 | 0.006 | 0.23 |

| Support for radicalism | 2.14 | 1.05 | 2.10 | 0.98 | −2.51 | 0.640 | 0.03 |

| 95% CI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | Lower | Upper | t | p | η2p | |

| Study 1 | |||||||

| Intercept | 3.71 | 0.07 | 3.55 | 3.86 | 47.76 | < 0.001 | 0.16 |

| Muslims vs non-Muslims | −0.63 | 0.15 | −0.94 | −0.32 | −4.01 | < 0.001 | 0.07 |

| Age | −0.12 | 0.14 | −0.40 | 0.14 | −0.91 | 0.360 | 0.00 |

| Sex | 0.18 | 0.13 | −0.08 | 0.46 | 1.38 | 0.174 | 0.00 |

| Support for non-normative action | 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.43 | 4.09 | < 0.001 | 0.07 |

| Study 2 | |||||||

| Intercept | 3.66 | 0.03 | 3.19 | 3.32 | 100.99 | < 0.001 | 0.22 |

| Muslims vs non-Muslims | 0.57 | 0.06 | 0.44 | 0.71 | 8.49 | < 0.001 | 0.10 |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.75 | 0.451 | 0.00 |

| Sex | −0.09 | 0.06 | −0.21 | 0.03 | −1.38 | 0.165 | 0.00 |

| Support for non-normative action | 0.31 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 0.37 | 8.42 | < 0.001 | 0.10 |

| Study 3 | |||||||

| Intercept | 3.29 | 0.03 | 3.23 | 3.35 | 105.71 | < 0.001 | 0.26 |

| Muslims vs non-Muslims | 0.63 | 0.06 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 9.85 | < 0.001 | 0.13 |

| Age | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.38 | 0.701 | 0.00 |

| Sex | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.11 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.941 | 0.00 |

| Support for non-normative action | 0.30 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.36 | 8.89 | < 0.001 | 0.11 |

| 95% CI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | Lower | Upper | t | p | η2p | |

| Support for activism | |||||||

| Intercept | 2.92 | 0.03 | 2.85 | 3.01 | 77.62 | < 0.001 | 0.26 |

| Muslims vs non-Muslims | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.36 | 2.81 | 0.005 | 0.02 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.91 | 0.369 | 0.00 |

| Sex | 0.09 | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.24 | 1.25 | 0.211 | 0.00 |

| Support for radicalism | 0.53 | 0.03 | 0.45 | 0.60 | 14.43 | < 0.001 | 0.24 |

| Support for radicalism | |||||||

| Intercept | 2.13 | 0.03 | 2.06 | 2.20 | 60.55 | < 0.001 | 0.26 |

| Muslims vs non-Muslims | −0.11 | 0.07 | −0.25 | 0.02 | −1.57 | 0.117 | 0.00 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −2.75 | 0.006 | 0.01 |

| Sex | −0.17 | 0.07 | −0.31 | −0.03 | −2.51 | 0.012 | 0.01 |

| Support for activism | 0.46 | 0.03 | 0.40 | 0.52 | 14.43 | < 0.001 | 0.24 |

3.2. Are Muslims More Supportive of Violent Actions?

Table 1 presents the mean scores of Muslims and non-Muslims on our scale of support for NNA. Tests of significance, controlling for age, gender, and support for NA reported in Table 4, indicate in each study no reliable differences between Muslims and non-Muslims in the level of support for non-normative actions. Note that in each study, Muslims do support violent actions significantly more than non-Muslims when scores on the measure of support for NA are not considered in the equation (see Table 1). The only exception is the scale of radicalism of Moskalenko and McCauley [25] used in Study 3 where even when activism is not considered, the analysis does not detect a greater radicalism among Muslims (see Table 1). Overall, this preliminary evidence is strongly supportive of COMRAD in showing that because activism and radicalism are often confounded in the real-world, studies of violent radicalism that do not control for the effect of (nonviolent) activism may reveal misleading results.

| 95% CI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | Lower | Upper | t | p | η2p | |

| Study 1 | |||||||

| Intercept | 2.29 | 0.07 | 2.15 | 2.43 | 31.73 | < 0.001 | 0.13 |

| Muslims vs non-Muslims | −0.21 | 0.15 | −0.51 | 0.09 | 1.36 | 0.174 | 0.00 |

| Age | −0.33 | 0.12 | −0.58 | −0.08 | −2.61 | 0.010 | 0.03 |

| Sex | 0.00 | 0.12 | −0.24 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.975 | 0.00 |

| Support for normative action | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.37 | 4.09 | < 0.001 | 0.07 |

| Study 2 | |||||||

| Intercept | 2.52 | 0.03 | 2.45 | 2.59 | 73.17 | < 0.001 | 0.14 |

| Muslims vs non-Muslims | 0.07 | 0.07 | −0.07 | 0.22 | 0.94 | 0.347 | 0.00 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.00 | −0.07 | −1.77 | 0.076 |

| Sex | 0.05 | 0.07 | −0.08 | 0.19 | 0.783 | 0.453 | 0.00 |

| Support for normative action | 0.34 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.42 | 8.42 | < 0.001 | 0.10 |

| Study 3 | |||||||

| Intercept | 2.34 | 0.03 | 2.27 | 2.41 | 68.23 | < 0.001 | 0.14 |

| Muslims vs non-Muslims | 0.02 | 0.07 | −0.12 | 0.17 | 0.34 | 0.729 | 0.00 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −2.16 | 0.031 | 0.01 |

| Sex | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.18 | 0.08 | −0.71 | 0.474 | 0.00 |

| Support for normative action | 0.36 | 0.04 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 8.89 | < 0.001 | 0.11 |

3.3. Test of a Comprehensive Model of Group-Based Relative Deprivation

Exploratory analyses of Study 1’s data, detailed in the Supporting Information (Tables S8–S12), guided us in developing the comprehensive model presented in Figure 1. In Study 1, the cognitive and affective components of GRD were significant predictors of support for normative actions (Table S8) but not of support for non-normative actions where only group-based contempt had a statistically significant effect (see Table S9). Our expectations concerning spurious relationships were borne out in Study 1 and replicated in Studies 2 and 3 (see Tables S10–S12). Table S10 shows that there is essentially no relationship between GRD and radicalism when activism and contempt are statistically controlled. In contrast, Table S11 shows that GRD and especially the affective component of anger remain highly predictive of activism, even when controlling for radicalism and contempt. Finally, Table S12 shows that the relation between group-based contempt and radicalism does not seem spurious as it remains significant even when controlling for activism and anger.

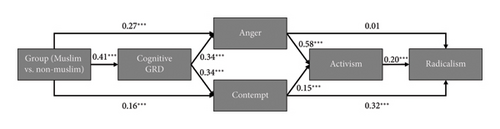

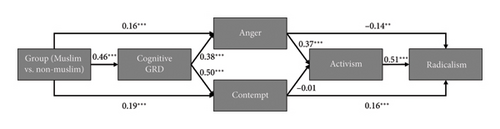

To rigorously evaluate our theoretical model, we performed a series of structural equation modeling analyses, utilizing AMOS Version 7 [52] and employing maximum likelihood estimation, with data drawn from Studies 2 and 3. Confidence intervals for direct and indirect effects were computed using a bootstrap procedure (bias-corrected, N = 1000; [53]). A total of 10 paths were specified: three paths from participants’ group (Muslim vs. Non-Muslim) to contempt, perceived group-based deprivation and anger, two from group-based deprivation to both anger and contempt, and four paths from anger and contempt to both normative and non-normative actions. Normative action was linked with non-normative action (the model’s outcome; see Figure 1). In Study 2, this hypothesized model displayed adequate fit with the data, χ2 (df = 4, N = 17) = 21.88, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.99, IFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.09, p = 0.038, AIC = 55.88 (see Figure 2). The results from Study 3 further corroborated that the hypothesized model was an adequate fit with the data when using measures of NA and NNA similar to Study 1 and Study 2, χ2 (df = 4, N = 638) = 39.60, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.97, IFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.11, AIC = 73.60, and an excellent fit when using the scales of activism and radicalism of Moskalenko and McCauley [25]; χ2 (df = 4, N = 638) = 6.55, p = 0.16, CFI = 0.99, IFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.03, AIC = 40.55 (see Figure 3).

In line with our predictions, the analyses detected a serial indirect effect suggesting that Muslims perceived higher group-based deprivation than non-Muslims, which led them to experience more anger, fostering increased normative action tendencies, which, in turn, increased non-normative action tendencies, β = 0.01, 95% CI [0.01, 0.02], p < 0.001 (Study 2); and β = 0.03, 95% CI [0.02, 0.05], p < 0.001 (Study 3). Parameter estimates indicated that the serial indirect effect on normative action tendencies through anger and group-based deprivation was of β = 0.03, 95% CI [0.01, 0.05], p < 0.001 (Study 2); and β = 0.14, 95% CI [0.09, 0.19], p < 0.001 (Study 3). Conversely, the same mediation pathway did not predict increased non-normative action tendencies in Study 2, β = 0.00, 95% CI [−0.03, 0.03], p = 0.085, indicating that increased group-based deprivation and anger among Muslims increase non-normative action tendencies only to the extent that they increase mobilization into normative collective action first. In Study 3, however, the mediation pathway from group-based relative deprivation to non-normative action through anger was negative, β = −0.05, 95% CI [−0.09, −0.01], p < 0.001, indicating a protective role of anger (devoid of other emotional components) against radical attitudes and intentions (see Figure 3).

Finally, parameter estimates revealed an indirect effect of group-based deprivation through contempt, which directly fostered increased non-normative action intentions, β = 0.08, 95% CI [0.05, 0.13], p < 0.001 (Study 2) and β = 0.08, 95% CI [0.03, 0.13], p < 0.001 (Study 3).

4. Discussion

Violent radicalism represents a pressing global challenge. Understanding why people turn to political violence is needed to design appropriate interventions. Across three studies, we found that (1) Muslims living in the West do experience group-based relative deprivation but are not more likely to support political violence than non-Muslims; (2) correlations between measures of GRD and the support for violence (radicalism) drop to insignificant level when controlling for nonviolent activism; (3) correlations between GRD and support for nonviolent activism are strong and remain strong regardless of one’s level of radicalism; and (4) group-based contempt is uniquely predictive of the willingness to engage in radical group behavior, not group-based anger. These results raise questions about previous work claiming, or assuming, that Western-born Muslims are inherently more radical than others and that GRD can explain why this is so.

Putting together these findings in a comprehensive model (COMRAD), structural equation modeling analyses provided consistent support for the existence of two hypothesized pathways potentially conducive to violence. First, we observed a (novel) corroboration of the “stairway” process, whereby GRD-driven anger fuels radicalism through increased activism intentions. This pathway coherently integrates a substantial body of past research, indicating GRD as a primary predictor of normative collective action [30], with more recent studies suggesting that GRD may also explain the endorsement of radical ideologies. However, corroborating results from Tausch et al. [26], the second pathway specifies that GRD-driven contempt directly and more strongly impacted radical intentions than group-based anger, regardless of support for normative actions. Together, these findings represent the first successful attempt at providing an integrated theory of the cognition and emotion involved in radical group behavior, with immediate methodological, theoretical, and policy implications.

First, violent extremism researchers need to make sure that their findings are not confounded with nonviolent activism. Correlations between GRD and support for political violence can spuriously derive from the relations of these variables with nonviolent activism. When using the scales of Moskalenko and McCauley [25]; researchers interested in radicalization sometimes use only the radicalism scale (see [53]). We recommend using both the radicalism scale and the activism scale in order to distinguish between factors that are specifically related to extremism from those that may in fact be primarily related to nonviolent activism.

Second, by supporting COMRAD, the present research offers a significant theoretical advance over existing work. Delineating the specific role that different intergroup emotions play in shaping behavior is an important part of the contribution that psychology has to offer. There are currently conflicting results regarding the role of group-based anger, with some recent research claiming that it predicts support for violence while earlier studies suggested that it predicts primarily support for normative collective actions (see [47]). In three studies, we find that the cognitive component of GRD can predict both group-based anger and group-based contempt and, further, that unlike contempt, group-based anger does not uniquely predict support for political violence. The simultaneous confirmation of the two pathways described above allows us to claim that the psychological experience of contempt differs radically from that of anger, despite being closely related. People can experience a sense of contempt, as Tausch et al. [26] argued, when confronted with the idea that their very existence does not matter. This role of contempt in radicalism is converging with Significance Quest Theory [2] and the hypothesis that the need for personal significance (the need to matter, to be somebody) is the main underlying motivation for extreme acts of violence such as suicide bombing.

Our results provide ecologically valid evidence to reassert the importance of distinguishing contempt and anger. When people are angry, they will protest but they think a solution will be found and they seek to maintain the relationship [26]. We do not usually become violent with people with whom we want to keep in touch. Thus, group-based anger, in and of itself, predicts primarily nonviolent activism. But when group-based contempt is experienced, people feel that their claims are not even recognized and they no longer want to maintain the relationships. As a result, aggression against the other party becomes a possibility.

One surprising and perhaps telling finding in Study 3 is that group-based anger predicts stronger activism while being, at the same time, negatively related to radicalism (see Figure 3). The more anger is felt and reported, the less support there is for the use of radical tactics (see also [19]). Sharpening an explanation for this unpredicted result will require more research, but it immediately leads to some policy implications following the present work. If group-based anger leads to the endorsement of group violence, as suggested in recent research (e.g., [19, 20]), then policies seeking to prevent the expression of group-based anger may be pursued. In democratic states, group violence is usually perceived as unacceptable. In contrast, if group-based anger leads primarily to be oriented toward normative collective action, as demonstrated here, there is no reason to try to prevent its expression. To the contrary, in a democratic system, one should protect and defend the freedom to express one’s opinion in a peaceful manner. Policies seeking to restrict the right to protest may be precisely what could turn anger into a sense of contempt and so inadvertently foster group violence, as shown in recent political events in France (see [44]). Other evidence obtained within this series of studies indicates that policies put forward by the French government and specifically designed to deal with Islamic radicalization had counterproductive effect, increasing rather than decreasing radicalism among French Muslims [55]. Empirically based understanding of the psychology of collective behavior can be useful to develop more effective policies in the prevention of political violence and avoid these unintended effects.

5. Limitations

This research may have important theoretical, methodological, and policy implications, but it nevertheless suffers from multiple limitations that need to be kept in mind. A first limitation is the correlational design used here. It implies that we have studied the relationship between variables that may be important to understand political violence, but we are not in a position to state which variable is a cause and which one is an effect. Thus, when we use the word “effect,” this must be read as a “statistical” effect, a convenient way to describe significant relationships among the variables. We cannot assert that experiencing the intergroup emotion of anger will result in supporting normative collective actions. Still, given the state of knowledge in this area and knowing that all relevant research linking GRD with violent radicalism is correlational in nature, it follows that what is needed before going to an experimental phase in the research process is to make sure that we have established valid relationships. Our first goal was precisely to test whether there is any convincing relationship between group membership, GRD, and violent radicalism. To achieve this goal, it was necessary to follow the cross-sectional method used in previous relevant research in order to show that we can replicate previous results and then test for a potential confound. Furthermore, on ethical grounds, experimental work that creates, rather than prevent, politically motivated and harmful acts, can be problematic.

This leads to a second limitation concerning our measures of support for normative and non-normative actions. These are measures of attitudes and intentions. As such, the results have no direct bearing on the explanation of behavior per se. We have studied cognitive radicalization rather than behavioral radicalization [56]. This is an important limitation that is again shared with many existing studies. From a psychological point of view, it can be argued that testing hypothesis about the factors that can explain why people support violent actions is nevertheless important. Given that past research showed a link between cognitive and behavioral radicalization [56], and given the widespread view that engaging in terrorism or political violence is the result of a radicalization process (cognitive radicalization), it can be justified to study the latter to inform the former.

A third limitation is with the sample of Study 1 that is severely imbalanced in terms of the number of Muslim and non-Muslim participants. This imbalance can have unknown and uncontrolled effects of the results. For this reason, we made sure in Study 2 and in Study 3 to have larger samples and an approximately equal number of Muslim and non-Muslim participants. A fourth limitation concerns some of the measures of the various constructs. It can be argued that some items do not adequately represent the underlying construct or that they were more relevant for Muslims than for non-Muslim participants. The latter possibility would be indicated by a discrepancy in missing data between the two groups, something that we did not observe. After the debriefing, the participants were invited to comment on their participation and we did not notice any concern with the relevance of some questions.

It is true that certain items were perhaps ambiguous or less than ideal but all the measures used in the statistical analyses are multi-item scales with an acceptable level of reliability. This means that the content of a single item is unlikely to drive the overall pattern of response. Nevertheless, improvements are always possible, and several of them were implemented in Study 3: a three-item measure of contempt (instead of two), a five-item measure of the cognitive component of GRD (instead of two), and the addition of the behavioral intention measure of activism and radicalism of Moskalenko and McCauley [25]. Thus, the results must be appraised by considering these various points and importantly, in light of the fact that three distinct studies were conducted at three distinct periods (in 2020, 2021, and 2022) in order to test the robustness of the results. Given that the findings are consistent across the different studies, one can have a reasonable level of confidence in the conclusions that we have drawn.

A final limitation concerns the generality of our results. Because our samples in Study 2 and Study 3 are truly diverse in terms of age, occupations, or regions across France, we trust that the results reflect accurately this national context. However, we have no evidence for other national contexts or other types of movements. Some variations across cultures can be anticipated. We would not expect the present results to offer an adequate basis to infer intergroup dynamics within authoritarian states where the public expression of discontent implies the risk of being arrested. However, the strong theoretical and empirical grounding of our research suggests that our findings should be relevant across contexts and movements, at least within Western democratic states.

We argue that, in Western democratic states, when people feel group-based anger, they turn to group action, using the available democratic means of protest. When these normative actions motivated by GRD are consistently repressed, the likelihood that activists will turn to political violence increases [1, 3, 39]. This is a dynamic explanation that contextualizes GRD within intergroup relations and seeks to go beyond the view of GRD as primarily an individual psychological predisposition to violence. In the staircase model of terrorism, Moghaddam [35] argued that “the vast majority of the people, even when feeling deprived and unfairly treated, remain on the ground floor” (p. 161). This viewpoint seems quite consistent with the observations made in the present research. Still, given the various limitations noted above, there is a strong need for more research as we are only beginning to understand how normative and non-normative collective actions may be related, and how various intergroup cognitions and emotions may arise and be involved in shaping intergroup dynamics.

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Université Clermont Auvergne (IRB00011540-2021-91). All participants provided informed consent electronically.

Disclosure

An earlier version of this manuscript has been presented as a preprint, Guimond et al. [57]. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/35xuj_v1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research was facilitated by funding from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR), France (Grant No. ANR-18-ORAR-0003).

Supporting Information

A pdf document, Supporting Information-GRD JTSP, can be accessed through the OSF project page at https://osf.io/6hvku/?view_only=1adafd29b1bc4dcfb174e8bedc278fd7. This document provides the complete list of all the items used in the present research, in all three studies, as well as additional tables and analyses describing the samples not reported in the text.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

All the data backing up the present research, as well as relevant supporting analyses and tables, can be openly accessed through the OSF project page at https://osf.io/6hvku/?view_only=1adafd29b1bc4dcfb174e8bedc278fd7.