Hypothermic Low Flow Fibrillation for Unclampable Aorta in Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting: Alternative to Off-Pump CABG

Abstract

Background: Severe calcific disease of the ascending aorta may prohibit cross-clamping during coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) due to unacceptable morbidity and mortality associated with atheroembolic complications. Clampless hypothermic noncardioplegic low flow fibrillation (HLFF) may minimize neurologic complications while allowing for complete revascularization.

Methods: From 2002 to 2019, 142 patients with unclampable aorta (UCA) underwent isolated CABG using clampless HLFF. Short-term and long-term outcomes were compared with an isolated conventional on-pump CABG cohort (n = 268) risk-matched (RM) for type of CABG, STS score, age, and sex.

Results: UCA and RM cohort patients were comparable in terms of age (73.7 ± 7.8 vs. 72.7 ± 8.7, p = 0.281), sex (34.4% vs. 32.5% female, p = 1.000), STS score (4.01 ± 3.43 vs. 3.80 ± 3.33, p = 0.539), and number of diseased vessels (p = 0.323). 90% of patients underwent central cannulation; UCA group patients received a comparable number of arterial (p = 0.432) or venous grafts (p = 0.493). Incidence of stroke was 6.3% in the UCA cohort and 2.6% in the RM cohort (p = 0.059). Need for reoperation, postoperative transfusions, incidence of atrial fibrillation, and renal impairment was similar (all p > 0.050). UCA patients spent a longer time on the ventilator, in the ICU, and in the hospital (all p = 0.001). Operative mortality was not different between UCA and RM groups (3.5% vs. 4.5%, p = 0.797) as was all-cause mortality over long-term follow-up (p = 0.093).

Conclusions: While a higher incidence of stroke was observed, without reaching statistical significance, hypothermic fibrillatory arrest remains a valuable and safe tool for coronary revascularization in UCA patients, offering comparable short-term and long-term survival outcomes allowing for complete revascularization.

1. Introduction

The rise of an increasingly aging patient population undergoing more complex cardiac surgical procedures is frequently associated with encounters of atherosclerotic disease of the ascending aorta, ranging from isolated plaques to diffuse circumferential involvement (porcelain aorta) [1]. Atherosclerotic disease of the ascending aorta precluding cross-clamping and manipulation of the ascending aorta during coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) remains a formidable surgical challenge. Unclampable aorta (UCA) has been shown to be an independent risk factor for perioperative stroke and mortality in cardiac surgery given the risk of distal embolization of atheromatous materials during aortic manipulation [2, 3].

To mitigate complications associated with manipulating UCA during CABG, various modifications have been described over the years; however, there is no established consensus on the standard surgical approach. One such strategy involves off-pump CABG with Y composite grafts from single or bilateral internal mammary grafts, known as the total anaortic technique [4–6]. Despite its potential advantages, including avoidance of UCA manipulation, the adoption of this approach has decreased due to a declining number of OPCAB and the significant learning curve required for mastery [7]. Consequently, many surgeons hesitate or are not comfortable in employing this technique. Alternatively, other strategies, such as replacing the ascending aorta under hypothermic circulatory arrest as well as on-pump beating heart, have been explored, albeit also involving complex procedures [5, 8, 9]. Thus, there arises a need to explore alternative methods to approach this complex problem.

In our practice, we routinely utilize a clampless strategy involving hypothermic noncardioplegic elective fibrillatory arrest for distal revascularization paired with brief periods of circulatory arrest and/or the use of devices for proximal anastomoses. This approach aims to minimize manipulation of the ascending aorta while ensuring effective revascularization. It serves as a viable alternative for surgeons who may not be comfortable performing OPCAB. The objective of this study was to compare the morbidity and mortality outcomes of patients with UCA undergoing hypothermic fibrillatory arrest during CABG to a risk-matched (RM) control cohort of conventional on-pump CABG. We hypothesized that patients treated with hypothermic low-flow fibrillation will have outcomes noninferior to those in the RM cohort of conventional on-pump CABG.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

This study was approved by the Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board with waived consent. We retrospectively reviewed all patients with UCA who underwent isolated CABG procedures without aortic cross-clamping at our institution between January 2002 and June 2019. Patients who underwent concomitant procedures were excluded.

2.2. Demographic Data

Demographic information, laboratory data, and in-hospital outcomes were extracted from our hospital’s electronic medical record (EMR). All variables were coded to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Adult Cardiac Surgery Database version 2.52 specifications, unless otherwise noted. STS mortality risk scores were calculated using the 2018 model. The presence of UCA or porcelain aorta (Supporting Figure 1) was defined as diffuse or concentric calcification as identified on preoperative imaging and confirmed with intraoperative epiaortic ultrasound. Mortality data were obtained by routine follow-up, our internal research data repository, or by query of the Mass General Brigham Research Patient Data Repository, which contains the EMR for all patients seen at our institution since 1989 as well as National Death Index data. Combining all methods, there was 99% follow-up for patient survival. Postoperative survival was calculated in months from surgery date through December 31, 2019, or date of death. The median follow-up time was 7.8 years (interquartile range (IQR): 4.5–12.4 years).

2.3. Surgical Approach

If the aorta was deemed clampable, we performed standard on-pump CABG with aortic cross-clamping. If aorta was deemed unclampable, we proceeded with hypothermic low flow fibrillation. Disease-free areas were identified for guided cannulation and proximal vein graft anastomoses. When feasible, the aorta served as the preferred site for cannulation; alternatively, femoral or axillary arteries were utilized. The right atrium was cannulated directly for venous drainage. During cardiopulmonary bypass, target temperature was 25 °C depending on the anticipated periods of low-flow fibrillatory arrest and/or total circulatory arrest. If the anterior surface of the ascending aorta was disease-free, a proximal vein graft anastomosis device was utilized. However, in the presence of scattered islands of atherosclerotic disease, proximal anastomoses were performed over a brief period of hypothermic circulatory arrest. Left sided grafts were performed using in situ left internal mammary artery (LIMA) or in situ right internal mammary artery (RIMA) tunneled through the transverse sinus. In cases of vein graft conduits, the proximal anastomoses were performed first. For control patients, proximal anastomoses were performed, while the aorta was cross-clamped.

Distal anastomoses to the right coronary (RCA) and left anterior descending arteries (LAD) were performed first to minimize lifting and distending the heart. Distal anastomoses to the posterior descending artery (PDA) and the circumflex obtuse marginal (OM) branches were performed when the desired level of hypothermia was reached, so the heart could safely be lifted at low flows to prevent distension of the left ventricle. Because the aorta was not clamped during cooling, diastolic arrest was achieved with systemic potassium or retrograde 8-to-1 hyperkalemic cold blood cardioplegia at the onset of ventricular fibrillation. In the presence of significant aortic incompetence, cooling was conducted at a slower pace to prevent premature fibrillation and distention of the left ventricle. In cases of distension, a left ventricular vent and, if necessary, a left ventricular ± pulmonary artery vent were utilized.

2.4. Outcomes of Interest

Primary outcomes of interest were operative mortality, 30 days stroke, myocardial infarction, and new-onset atrial fibrillation. Secondary outcomes included intensive care unit (ICU), postoperative length of stay (LOS), prolonged ventilation (defined as > 24 h), and 30-day readmissions. Causes of 30-day mortality as well as severity of 30-day stroke events were also assessed. Operative mortality included any death occurring in-house during the index admission or within 30 days of surgery, if discharged, as well as long-term follow up. Patients were followed up for a maximum of 10 years postoperatively. The overall survival across the entire follow-up period was assessed.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

In order to examine the additional burden of both UCA and the alternative cannulation on postoperative outcomes, a reference group of isolated CABG with corresponding number of anastomoses was identified. From this pool, we isolated a comparison cohort of patients using criteria which were developed a priori. A 1:2 match was sought using a 0.05 STS predicted risk of mortality (PROM) caliper. If multiple matches were available within that caliper, age and sex were the next criteria. If 2 subjects were not within the caliper, then nearest match on STS-PROM, age, and sex was used. A total of 268 STS PROM RM CABG patients were then compared to the 142 UCA subjects; 130 of whom were matched 1:2, 8 matched 1:1, and 4 could not be matched within parameters. Because the unmatched UCA patients clustered in the top-quartile of risk, the decision was made to retain these 12 cases and their 8 matched cases and to better represent the full risk profile of UCA cases as well as very-high risk CABG patients, rather than bias our findings away from more severe outcome differences. A sensitivity analysis was performed on the subset of 130 UCA and 260 matched cases to ensure that these cases were not exerting undue influence on our findings.

Normally distributed variables are presented as means ± standard deviation and compared using Student’s t-test with Levene’s test for homogeneity for variance. Non-normally distributed variables are expressed as medians with the IQR and were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages and compared using Fisher’s exact test. The observed to expected ratio (O: E) was calculated by dividing observed operative mortality by the STS PROM. Postoperative unadjusted survival was estimated by Kaplan–Meier analysis with log-rank tests. No corrections for multiple testing were made. All analyses were performed with R version 3.8, and p ≤ 0.05 was the criterion for significance.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Baseline Patient Characteristics

Baseline characteristics, stratified by UCA and RM cohorts, are summarized in Table 1. The UCA and RM cohorts were well balanced, with no differences in mean age (73.7 ± 7.8 for UCA vs. 72.7 ± 8.7 for the RM cohort, p = 0.281), sex distribution (34.4% female for UCA vs. 32.5% female for the RM cohort, p = 1.000), the mean STS score (4.01 ± 3.43 for UCA vs. 3.80 ± 3.33 for the RM cohort, p = 0.539), and the number of diseased vessels (p = 0.323). Further, there were no disparities between groups in terms of cardiac function (ejection fraction, p = 0.244) and heart failure status (p = 0.520) as well as cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes mellitus (42.3% for UCA vs. 44.4% for the RM cohort, p = 0.754), chronic kidney disease (10.6% for UCA vs. 11.2% for the RM cohort, p = 0.869), hypertension (88.0% for UCA vs. 87.3% for the RM cohort, p = 0.876), smoking status (15.5% for UCA vs. 9.0% for the RM cohort, p = 0.073), and family history of CAD (21.8% for UCA vs. 23.5% for the RM cohort, p = 0.805). Notably, compared to the RM cohort, UCA patients had a higher prevalence of peripheral vascular disease (37.3% for UCA vs. 21.6% for the RM cohort, p = 0.001), cerebrovascular disease (34.5% for UCA vs. 20.6% for the RM cohort, p = 0.004), and left main disease (51.4% for UCA vs. 40.3% for the RM cohort, p = 0.037).

| Variables | UCA cohort (n = 142) | Risk-matched cohort (n = 268) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 73.7 (7.8) | 72.7 (8.7) | 0.281 |

| Female, n (%) | 46 (34.4) | 87 (32.5) | 1.000 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 28.4 (5.6) | 28.5 (5.9) | 0.870 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 60 (42.3) | 119 (44.4) | 0.754 |

| CKD, n (%) | 15 (10.6) | 30 (11.2) | 0.869 |

| Creatinine, mean (SD) | 1.07 (1.31) | 1.29 (0.84) | 0.807 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 125 (88.0) | 234 (87.3) | 0.876 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 127 (89.4) | 239 (89.2) | 1.000 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 22 (15.5) | 24 (9.0) | 0.073 |

| Family history of CAD, n (%) | 31 (21.8) | 63 (23.5) | 0.805 |

| PVD, n (%) | 53 (37.3) | 58 (21.6) | 0.001 |

| CVD, n (%) | 49 (34.5) | 56 (20.6) | 0.004 |

| Previous MI, n (%) | 78 (54.9) | 146 (54.5) | 1.000 |

| HF within 2 weeks, n (%) | 55 (38.7) | 95 (35.4) | 0.520 |

| History of atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 12 (8.5) | 22 (8.2) | 1.000 |

| Previous cardiac surgery, n (%) | 6 (4.2) | 3 (1.1) | 0.070 |

| STS PROM, mean (SD) | 4.01 (3.43) | 3.80 (3.33) | 0.539 |

| Catheterization data | |||

| Ejection fraction, %, median (IQR) | 50 (45–60) | 50 (36–60) | 0.244 |

| LM disease, n (%) | 73 (51.4) | 108 (40.3) | 0.037 |

| Diseased vessels, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.5) | 0.323 |

| 2 | 27 (19.6) | 54 (19.9) | |

| 3 | 115 (83.3) | 210 (77.2) | |

- Note: CVD, cerebrovascular disease.

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HF, heart failure; MI, myocardial infarction; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; STS PROM, society of thoracic surgeons predicted risk of mortality.

3.2. Procedural Characteristics

Procedural characteristics are summarized in Table 2. In comparison to the RM cohort, patients in the UCA cohort experienced significantly longer cardiopulmonary bypass times [140 min (IQR, 112–172) versus 100 min (IQR, 80–121); p = 0.001]. Among UCA patients, 39.4% underwent circulatory arrest, with a median time of 7 min (IQR 5–12) to facilitate proximal graft anastomoses. Ascending aortic cannulation was performed in the majority of patients in each cohort. Notably, UCA cohort patients did not undergo inferior revascularization, and the number of distal grafts were comparable between the two groups (p = 0.17).

| Variables | UCA cohort (n = 142) | Risk-matched cohort (n = 268) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emergent operation, n (%) | 7 (4.9) | 16 (6.0) | 0.596 |

| Cardiogenic shock, n (%) | 4 (2.8) | 8 (3.0) | 1.000 |

| Preoperative IABP, n (%) | 15 (10.6) | 24 (9.0) | 0.599 |

| Perfusion time, minutes, median (IQR) | 140 (112–172) | 100 (80–121) | 0.001 |

| Cross-clamp time, minutes, median (IQR) | N/A | 75 (62–93) | |

| Circulatory arrest used, n (%) | 56 (39.4) | 1 (0.4) | 0.001 |

| Circulatory arrest time, minutes, median (IQR) | 7 (5–12) | NA | NA |

| Lowest systemic temperature, °C, median (IQR) | 24 (20–27) | 34 (32–35) | 0.001 |

| Arterial cannulation site, n (%) | |||

| Ascending aorta | 128 (90.1) | 249 (92.9) | 0.005 |

| Femoral artery | 4 (2.8) | 2 (0.7) | |

| Right axillary artery | 9 (6.3) | 5 (1.9) | |

| Venous cannulation site, n (%) | |||

| Right atrium | 116 (81.7) | 221 (82.5) | 0.963 |

| Femoral vein | 16 (11.3) | 30 (11.2) | |

| IMA use, n (%) | |||

| LIMA | 135 (95.1) | 250 (93.3) | 0.432 |

| RIMA or both | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.9) | |

| None | 7 (6.3) | 13 (4.9) | |

| Distal grafts, n (%) | |||

| 2 | 21 (14.8) | 50 (18.7) | 0.170 |

| 3 | 84 (59.2) | 126 (47) | |

| 4 | 32 (22.5) | 75 (28) | |

| 5 or more | 5 (3.5) | 17 (6.3) | |

| Intraoperative transfusion requirement, n (%) | |||

| RBC | 72 (50.7) | 101 (37.7) | 0.011 |

- Note: IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; RBC, packed red blood cell.

- Abbreviations: IMA, internal mammary artery; LIMA, left internal mammary artery; RIMA, right internal mammary artery.

3.3. Postoperative Outcomes

Postoperative outcomes are detailed in Table 3. During hospitalization, there were no significant differences observed in major morbidity outcomes between patients in the UCA and RM cohorts, including reoperation for bleeding (1.4% for UCA vs. 1.1% for the RM cohort, p = 1.000), new onset atrial fibrillation (22.5% vs. 16.8%, p = 0.184), new onset renal impairment (4.2% for UCA vs. 3.4% for the RM cohort, p = 0.782), and postoperative transfusion requirements (40.1% for UCA vs. 33.2% for the RM cohort, p = 0.179). However, UCA cohort patients exhibited a longer ventilation time [11 h (IQR, 7–16) versus 8 h (IQR, 5–13); p = 0.001], an extended ICU stay [65 h (IQR, 44–98) for UCA versus 47 h (IQR, 25–73) for the RM cohort; p = 0.001], and a prolonged overall LOS [9 days (IQR, 7–11) for UCA versus 7 days (IQR, 5–9) for the RM cohort; p = 0.001]. Nonetheless, there was no difference in 30-day readmission rates between the two cohorts (5.5% for UCA vs. 11.7% for the RM cohort, p = 0.051).

| Variables | UCA cohort (n = 142) | Risk-matched cohort (n = 268) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reoperation for bleeding, n (%) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (1.1) | 1.000 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 9 (6.3) | 7 (2.6) | |

| Recovered by discharge | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) | 0.059 |

| Requiring rehabilitation | 6 (4.2) | 3 (1.1) | |

| Died | 3 (2.1) | 2 (0.7) | |

| New-onset atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 32 (22.5) | 45 (16.8) | 0.184 |

| New-onset renal impairment, n (%) | 6 (4.2) | 9 (3.4) | 0.782 |

| Postoperative transfusion requirement, n (%) | |||

| RBC | 57 (40.1) | 89 (33.2) | 0.179 |

| Ventilation time, hours, median (IQR) | 11 (7–16) | 8 (5–13) | |

| Prolonged ventilation, n (%) | 22 (15.5) | 29 (10.8) | 0.001 |

| Total ICU time, hours, median (IQR) | 65 (44–98) | 47 (25–73) | 0.001 |

| LOS, days, median (IQR) | 9 (7–11) | 7 (5–9) | 0.001 |

| Operative mortality, n (%) | 5 (3.5) | 12 (4.5) | |

| O/E ratio | 0.88 | 1.18 | 0.797 |

| 30-day readmissions, n (%) | 8 (5.5) | 32 (11.7) | 0.051 |

- Note: RBC, packed red blood cell.

- Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; O/E, observed/expected.

3.4. Neurologic Outcomes

The overall incidence of stroke in the entire study cohort was 3.9%. Within the UCA cohort, 9 patients (6.3%) suffered a stroke, while in the RM cohort, 7 patients (2.6%) had a stroke (p = 0.059). Additionally, in both cohorts, 5 patients died as a consequence of neurologic impairment (1.2%), 9 patients (2.2%) required rehabilitation, and 2 patients (0.5%) recovered from all neurologic symptoms at time of discharge.

3.5. Survival Outcomes

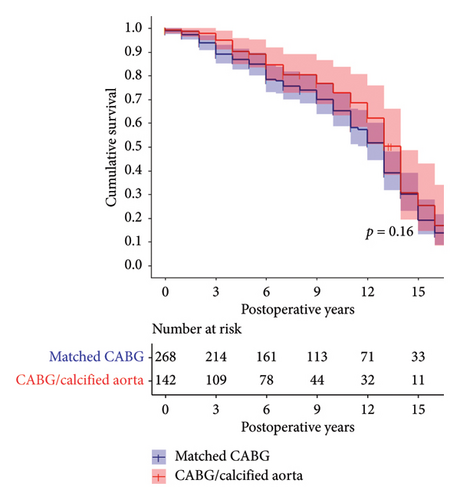

Operative mortality did not differ significantly between UCA and RM cohorts (3.5% vs. 4.5%, p = 0.797). However, the O: E ratio was lower in the UCA cohort (0.88 for UCA vs. 1.18 for the RM cohort). Survival rates at 1 year, 5 years, and 10 years for the UCA cohort were 91% (95% CI, 86–96), 70% (95% CI, 62–78) and 39% (95% CI, 30–49), respectively. Corresponding survival rates for the RM cohort were 91% (95% CI, 87–94) 73% (95% CI, 68%–79%) and 50% (95% CI, 43–58), respectively. Overall, survival over the entire follow-up period was comparable between the cohorts (log rank p = 0.093, Figure 1).

3.6. Sensitivity Analyses

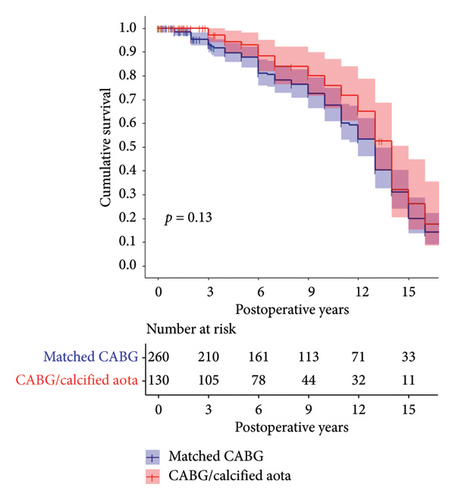

There were 12 UCA patients who could not be matched 1:2 clustered in the highest quartile of STS PROM scores (mean = 6.2 and median: 7.3). We examined whether these 12 patients and 8 matches were exerting undue effect on our findings by a sensitivity analysis that excluded these 20 cases. The results are presented in Supporting Table 1 and Figure 2. While their exclusion did affect the number of stroke, operative mortality, and prolonged ventilation events, the estimated survival was substantially similar between the UCA and matched CABG patients (p = 0.13).

4. Discussion

This study provides important insights into the use of hypothermic low-flow fibrillation for CABG in patients with UCA. The main findings of our study demonstrate that hypothermic low-flow fibrillation offers comparable short-term and long-term mortality outcomes to conventional CABG, with an acceptable stroke incidence. Additionally, this approach allows for complete revascularization, which is particularly beneficial for patients with complex atheromatous disease of the ascending aorta.

Numerous studies have documented a direct correlation between the extent of atherosclerotic disease in the ascending aorta and increased risk of post-CABG stroke [2, 10]. While routine CABG procedures have a stroke incidence of 1.3% [11], this risk can increase to 9%–15% in the presence of atheromatous disease in the ascending aorta [2, 10, 12]. These findings underscore the urgent need for surgical approaches that minimize aortic manipulation while ensuring effective revascularization, emphasizing the pivotal role of tailored operative strategies in mitigating stroke risk amidst atheromatous disease.

In patients where UCA is encountered, proposed management strategies depend on severity of aortic disease and include (1) the use of beating-heart off-pump total anaortic techniques avoiding central cannulation, cross-clamping, and proximal aortic anastomoses altogether by using LIMA, RIMA, both mammary arteries (BIMAs), or any combination of composite grafts; (2) on-pump beating heart CABG; (3) hypothermic fibrillatory arrest avoiding cross-clamping and enabling continuous perfusion of the heart in a relatively still operating field with proximal aortic anastomoses performed using a device or over short periods of circulatory arrest; (4) replacement of the ascending aorta under hypothermic circulatory arrest; or (5) hybrid approaches including the use of endoaortic balloon occlusion [13].

Our single center, retrospective experience with hypothermic low flow fibrillation underscores the viability and efficacy of this technique, with outcomes that highlight its potential as a safe and effective approach for this high-risk patient group.

Notably, patients in the UCA cohort experienced longer ventilation times, higher rates of prolonged ventilation, and extended ICU and hospital stays. While these findings may partly reflect the complexity of managing patients with extensive atheromatous disease, they likely also stem from baseline difference such as the higher prevalence of cerebrovascular and peripheral vascular disease in this group. Understanding these nuances is important when counseling patients and planning resource allocation for this particularly high-risk population.

4.1. OPCAB

The 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization recommend consideration of OPCAB with the no-touch technique in UCA patients [14]. However, it is crucial to highlight that this recommendation is contingent upon OPCAB surgical expertise, which is dwindling [7]. Recent research reveals a declining interest in OPCAB, as evidenced by a nationwide study reporting a significant decrease in its utilization from 21.1% in 2016 to 18.3% in 2019 [15]. Moreover, this study correlates hospital volume with patient outcomes, indicating superior outcomes in high-volume hospitals.

Despite the potential benefits of pursuing OPCAB, a meta-analysis involving over 100,000 patients across 22 studies suggests a possible association of OPCAB and poorer long-term survival compared to on-pump CABG [16]. Surgeons’ discomfort with off-pump techniques, particularly in patients with a hostile ascending aorta, further complicates revascularization. An in-depth exploration of the STS database reveals significant shifts in off-pump procedures over time. Initially peaking in 2002 and then again in 2008, their prevalence gradually declined, reaching only 17% of the total CABG procedures performed by 2012. Most centers conducted fewer than 50 off-pump cases annually, with 34% of surgeons performing no OPCAB procedures during the study period. This resulted in a mean of 10.4 ± 23.2 OPCAB cases per surgeon per year, with a median of 6.3 (IQR 1.7–26.8), underscoring the infrequency of such interventions. The modest number of cases per surgeon and institution underscores the significance of inadequate experience, particularly in complex scenarios such as encountering a case involving a porcelain aorta. Although OPCAB may offer benefits in specific high-risk subgroups such as UCA, the requisite expertise and skill of the operating surgeon remain indispensable. Consequently, we highlight in this paper the urgent need to provide surgeons with alternative and viable options that extend beyond conventional approaches, addressing the scarcity and complexity observed.

While substantial evidence supports the use of OPCAB, concerns persist regarding its ability to achieve optimal revascularization. Lev-Ran et al. [17] and the Danish on-pump versus off-pump randomization study (DOORS) [18] multicenter trial highlighted a significant proportion of patients undergoing the off-pump technique failing to achieve full revascularization. Moreover, the ROOBY trial and its follow-up (ROOBY-FS) further revealed disparities in graft patency and major adverse cardiovascular events between off-pump and on-pump groups, raising concerns regarding the long-term efficacy of OPCAB [19, 20].

Furthermore, while drawing upon data from the EXCEL trial, which compared percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with everolimus-eluting stents versus CABG, Benedetto et al. analyzed 923 CABG patients, among whom 652 underwent on-pump surgery and 271 underwent OPCAB. Despite similar disease extent, off-pump surgery was associated with lower rates of revascularization and increased risk of 3-year all-cause death compared to on-pump CABG [21].

4.2. Hypothermic Low Flow Fibrillation

In light of the challenges associated with OPCAB, the proposed technique of hypothermic low flow fibrillation emerges as a promising alternative, offering complete revascularization with acceptable mortality and stroke rates. Our findings, alongside those of Salenger et al. [10], who retrospectively analyzed outcomes of 71 consecutive patients with UCA undergoing clampless hypothermic circulatory arrest compared to 610 patients with partial side clamping during CABG. Similar to our experience, distal revascularization was achieved using hypothermic noncardioplegic myocardial preservation (30°C–32°C), although we tend to cool further down (20°C–25°C) during ventricular fibrillation. Proximal anastomoses were constructed during brief periods of circulatory arrest. In our UCA cohort, we used brief circulatory arrest in 39.4% of patients and proximal devices in the majority of patients.

In their hypothermic fibrillatory arrest cohort, Salenger et al. [10] found 30-day mortality rates of 2.8% and stroke rates of 1.4%, which were comparable to their conventional CABG cohort. In our experience, operative mortality was 3.5%, and the stroke rate was 6.3%. While our short-term and long-term mortality rates did not differ compared to our conventional CABG cohort, there was a trend toward a higher incidence of stroke (p = 0.059). This might be explained by the very high prevalence of baseline cerebrovascular disease in our patient cohort (34.5%), which was more than twice as high as in Salenger’s experience. Furthermore, the prevalence of cerebrovascular disease was higher in our UCA cohort compared to our conventional CABG cohort (34.5% vs. 20.6%, p = 0.004), which might in part explain the higher incidence of stroke in our UCA cohort. Importantly, Salenger et al. [10] found no difference in the total number of bypass grafts performed between hypothermic fibrillatory arrest cohorts and side clamping CABG cohorts. This is consistent with our own experience with no difference in the number of arterial and venous bypass grafts between UCA and RM groups, suggesting potential for complete revascularization.

We believe that hypothermic fibrillatory arrest is a safe strategy for patients with severe atheromatous disease of the ascending aorta (or porcelain aorta) where clamping would likely lead to an adverse neurological outcome that allows for complete revascularization with acceptable mortality and stroke rates. Fibrillatory arrest together with left ventricular venting and local vessel control of coronary arteries recreates operating conditions that most surgeons are familiar with and might be adopted faster than off-pump beating heart techniques. For proximal anastomoses, both short periods of circulatory arrest as well as the use of proximal devices appear to be safe. In our experience, median circulatory arrest times of 7 min are typically well tolerated and consistent with other reports [22, 23].

5. Limitations

This study is limited by issues inherent to its single-center retrospective design. Although risk-matching allowed us to compare the two cohorts, there is possibility of residual patient selection bias. While study cohorts were matched for type of CABG, STS score, age, and sex, there was residual imbalance in major baseline characteristics such as cerebrovascular disease which might in part explain the trend toward higher stroke incidence in the UCA cohort. Although our sensitivity analysis excluding unmatched cases indicated consistent survival estimates between the UCA and CABG patients, the possible selection bias warrants caution in generalizing these findings. Lastly, postoperative data such as left ventricular ejection fraction at discharge, biomarkers of myocardial injury, and detailed reasons for readmissions or need for revascularization were not uniformly available and therefore could not be included in the analysis.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study underscores the significance of tailored operative strategies for patients with severe atheromatous disease of the ascending aorta undergoing CABG. The clampless hypothermic fibrillatory arrest technique described here emerges as a valuable alternative, offering effective revascularization with reduced aortic manipulation. However, the observed trend toward a higher incidence of stroke indicates that this approach cannot be universally considered a safe tool. Despite this, our findings demonstrate comparable short-term and long-term survival outcomes between patients undergoing hypothermic fibrillatory arrest and conventional on-pump CABG. These results suggest that with careful patient selection and individualized risk assessment, hypothermic fibrillatory arrest can still be a valuable tool in specific clinical scenarios, particularly for surgeons who may not be comfortable with OPCAB techniques. Further studies are needed to better understand the patient subgroups that may benefit from this technique and to refine methods that may mitigate the associated risks.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Tsuyoshi Kaneko is a speaker for Edwards LifeSciences, Medtronic, and Abbott Vascular. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Thais Faggion Vinholo and Andreas Habertheuer are joint first authors.

Funding

This research was supported by the Bulens Family.

Acknowledgments

The authors have nothing to report.

Supporting Information

Supporting Table 1: Sensitivity Analysis’ key characteristics and in-hospital patient outcomes.

Supporting Figure 1: Porcelain aorta. Preoperative noncontrast CT scan of a representative patient with severe diffuse calcification of the ascending aorta extending into the arch. A. Coronal view. B–E. Axial views at the level of the proximal ascending aorta, mid ascending aorta at the level of the pulmonary artery bifurcation, aortic arch, and the level of the mitral valve.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The clinical data used to support the findings of this study are restricted by the MGB IRB in order to protect PATIENT PRIVACY. Data are available from the MGB Clinical Data Sharing Committee for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. Contact the corresponding author for more information.