Diversity and Some Biological Aspects of Fishes From a River in the National Park of Ethiopia

Abstract

The Denkoro River is the largest river in Borena Sayint National Park (BSNP) of Ethiopia. Many studies have been conducted on the terrestrial biodiversity of the park. However, there are no baseline data on the fish biodiversity of the park. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the diversity, determine the biology of the dominant fishes, and compile baseline data. Fish specimens were collected using gillnets (4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 cm stretched mesh sizes), monofilaments (5, 10, 15, and 20 mm mesh size), and hook and lines. Fish samples in the Denkoro River were collected in wet (September) and dry (December) seasons, 2022. A total of 398 fish specimens were collected from three sites in both seasons. Five fish species, Labeobarbus intermedius, Garra dembecha, Clarias gariepinus, Labeobarbus beso, and Oreochromis niloticus, were identified from the river. The diversities (H′) of fish species in the Wachau, Buke, and Kernemariam sites in the dry season were 1.45, 0.95, and 0.64, respectively. During the wet season, fish species diversity was lower than that in the dry season, with Shannon diversity indices of 1.33, 1.18, and 0.93 at the Wachau, Buke, and Kernemariam sites, respectively. L. intermedius was the most abundant species, with 42.9% of the total catch. The length–weight relationships of L. intermedius and L. beso followed a curvilinear pattern, described by the equations TW = 0.005TL3.12 and TW = 0.01TL2.94, respectively. In all sites, females were more numerous than males and statistically significant (Chi-square, p < 0.05). For sustainable fish conservation and development, further research on fishing activities, feeding habits, and fish biology is needed. Important management measures such as regulated fishing activities, habitat restoration, and spawning ground protection should be performed in the area.

1. Introduction

Freshwater bodies, though covering only about 2.5% of the Earth’s total water surface, are vital for sustaining ecological balance and human well-being. They offer essential ecosystem services that benefit both nature and society [1]. However, freshwater fish face increasing threats from human activities such as pollution, water diversion, habitat destruction, and the introduction of invasive species. This highlights the growing need for research and conservation efforts to protect these species [2].

Ethiopia possesses significant water resources, with approximately 13,637 km2 of standing water bodies and 8065 km of rivers, offering substantial potential for fisheries development. The country primarily engages in inland freshwater fishing, utilizing diverse aquatic habitats such as the Rift Valley lakes (notably Lakes Chamo, Abaya, and Ziway), Lakes Tana and Hashenge, as well as the Baro and Tekeze Rivers [3]. While fishing activities occur across various water bodies, commercial fishing is concentrated around Lakes Chamo, Ziway, and Tana, which serve as key hubs for fishery resources in Southern and Northwestern Ethiopia. The sector employs approximately 15,000 fishers, reflecting a developing industry with considerable growth potential. Historical data from 2002 indicate an average fish production of around 12,300 tons, underscoring opportunities for expansion and increased commercialization in Ethiopia’s freshwater fisheries [4].

Ethiopia’s distinctive aquatic ecosystems and growing workforce create a strong foundation for expanding its fishing industry, offering potential economic gains and improved food security. As the sector progresses, adopting sustainable fishing practices will be crucial to safeguarding these essential freshwater resources [4].

Ethiopia’s freshwater ecosystems support over 200 fish species, with around 40 being unique to the country, demonstrating its remarkable biodiversity [5]. The diverse ecological conditions of its lakes and rivers provide a suitable environment for various freshwater fish to thrive. Additionally, these aquatic habitats host a wide range of life forms from large mammals such as hippopotamuses to microscopic organisms, showcasing the richness of Ethiopia’s water bodies. This thriving aquatic biodiversity offers significant opportunities for the expansion of the country’s fisheries industry.

Despite growing initiatives to raise awareness of the role of fisheries in food security and nutrition, as well as the expansion of aquaculture, research on fish biology has largely focused on specific regions, leaving many small and medium-sized rivers understudied due to security challenges, harsh environmental conditions, and inadequate infrastructure. One such underexplored water body is the Denkoro River, one of the largest within the Borena Saiyt National Park, where the absence of fishery studies has resulted in a significant lack of biodiversity data. This study aims to fill that gap by developing effective conservation and management strategies for fishery resources, specifically by identifying fish species composition, assessing species diversity across wet and dry seasons, determining the relative abundance of various species, and analyzing the spatial and temporal distribution of fish across different sampling locations. The findings will provide critical insights for sustainable fisheries management and biodiversity conservation in the Denkoro River.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.1.1. General Description of the Study Area

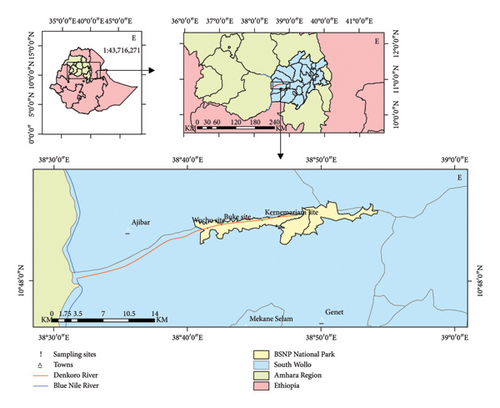

The study was conducted at the Denkoro River, one of the tributaries of the Blue Nile located in the Mehal Sayint District of South Wollo, Ethiopia. The study area is located about 600 km far from Addis Ababa (the capital city of Ethiopia). Geographically, the area lies between the coordinates of 10° 50′ 45.4″ and 10° 53′ 58.3″ N ‘and 38° 40′ 28.4″ and 38° 54′ 49″ E with an estimated area of 1070.77 km2. The Mehal Sayint District is bordered on the south by the Borena District, on the West by the Enebssie Sarmidir District, on the north by the Sayint Adjibar District, and on the east by the Legambo District [6]. The name Denkoro, deaf in English, is given to a person who was absent during mass gathering to welcome the king in ancient times in the area because he had not heard the information.

The Denkoro River originates at the plateau called Lemsk in the Borena Sayint National Park, and it crosses the three kebeles of the Mehal sayint District called Wojed, Kotet, and Harwuha kebele, and it joins to the Blue Nile River. There are many tributary rivers such as Gelgel Denkoro that drain into the Denkoro River, which joins the Blue Nile River at its western end after crossing the park. In addition, many ponds and water holes are found inside the park that joins to the Denkoro River. The local farmers use these water sources for small plots of land irrigation to cultivate potatoes, maize, onion, and chilly in the dry season. The area is wet all around the year because of the presence of the dense forest locally called the Denkoro forest cover and topography that increases precipitation and causes rain. Generally, there is no scarcity of water in the area.

2.1.2. Flora

The Denkoro River is one of the hotspot areas and the backbone for the survival of different wildlife in the park; hence, it is used for biodiversity conservation. The national park contains the greatest amount of indigenous forests and diverse flora and fauna in northern central Ethiopia. It is endowed with 354 vascular plant species representing 265 genera, and 95 families have been identified within the park [7]. The perennial open savanna grasses characterize the vegetation of the study area. These grass species grow up to 2.5 m. There are also a variety of shrubs and shrub-like trees.

2.1.3. Fauna

In the study area besides fish, other vertebrate animals are living in and around the rivers. Different species of amphibians and birds are very common in the waters and around the study sites. Different kinds of small snakes and frogs are frequently observed around the sites. However, the most diverse vertebrate animals are aquatic birds. There are different bird species around Denkoro River where many of them are aquatic birds that eat fishes [8].

2.1.4. Site Selection

Before starting regular sampling programs, a reconnaissance survey was conducted to fix the sites. Three sampling sites were selected along the river, taking into account the velocity of flow of water, habitat types, interference by human beings and other farm animals, substrate type of sediments and accessibility, depth of water, and road access. The sites were given names as follows: Kernemariam site (KS), Buke site (BS), and Wachu site (WS) (Table 1 and Figure 1). These subareas are, namely, the Kernemariam site found around the Kernemariam church at Wojed kebele, which is about 15 km downstream of the origin of the river; the Buke site found around Guba village at Kotet kebele, which is approximately 30 km far from the origin of the river; and the Wachu site found in Harwuha kebele, which is approximately 58 km far from downstream of the origin of the river. These sites were found in the Mehal Sayint District under three kebeles, namely, Wojed, Kotet, and Harwuha, respectively.

| Site | Mean depth (m) | Mean water temperature (°C) | Mean pH | Elevation (m) | Habitat nature | GPS coordinate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kernemariam | 2.8 | 23.5 | 7.24 | 1545 | Clear water, mud, and sandy | 10°53′06″N |

| 38°45′35″E | ||||||

| Buke | 2 | 24.3 | 7.12 | 1534 | Muddy sand | 10°53′23″N |

| 38°42′27″E | ||||||

| Wachu | 1.8 | 25.2 | 7.21 | 1490 | Clear water and rock gravel | 10°53′54″N |

| 38°40′59″E |

Kernemariam site (KS) (10°53′06″ N, 38°45′35″E): The sites are located 2 km south of the Kernemariam church. The site is characterized by relatively less human interference. The water of the sites is found in a very deep gorge formed by rocky cliffs. The substratum of the rivers is composed of mud, sand, and pebbles.

Buke site (BS) (10°53′23″N, 38°42′27″E): This site is located at about 3 km in southwest of Guba village. Human interference is very high, i.e. it is a place where local communities fetch water, a swimming place for local children, and a drinking site for cattle and herds. The water flows in the deep and narrow gorge. Mud, sand, and pebbles characterize the riverbed of the site.

Wachu site (WS) (10°53′54″N 38°40′59″ E): The site is about 5 km from the village. Some waterfalls are present at this station with relatively high human interference. The vegetation cover at the site is very low except in the wet season. The riverbed is composed of mud, gravel, pebbles, sand, and bedrock.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Field Sampling

Data collection took place during two distinct seasons, the wet season (late September 2022) and the dry season (late December 2022), with each site sampled twice, once in each season. Various fishing methods were employed, including gill nets of different mesh sizes (4, 6, 8, and 10 cm stretched mesh), monofilament nets (5, 10, 15, and 20 mm stretched mesh), and hooks and lines where gill netting was not feasible. Gill nets were set diagonally across the river in the late afternoon (4:30 PM) and retrieved the following morning (7:30 AM) after approximately 15 h. Monofilament nets were set for one-hour intervals and checked hourly for three consecutive hours, while hooks and lines were placed at dawn and inspected early in the morning. Fish species were identified on-site immediately after capture, followed by measurements of total length (TL) and total weight (TW) to the nearest 0.1 cm and 0.1 g, respectively. Fish were dissected in the field to identify sex of the fishes. Representative samples from each species were preserved in plastic jars containing 10% formalin, labeled with necessary information, and transported to the Department of Biology at Wollo University in Dessie Town for further analysis and identification for confirmation. Note: the number of the fish species was low, and identification was not difficult that is why TL and TW were measured in the field. My student has sent the image of the fish via telegram when he got some difficulty for identification, and I have identified easily the fishes. The fish specimen brought to the lab was for further conformity in case new species were probably recorded from the river. However, we have confirmed no new species, and they were the ones identified via telegram.

2.2.2. Laboratory Studies

In the Biology Department, at Wollo University, a specimen of fish was soaked in tap water for one day to wash the formalin and was identified by using identification keys [9, 10].

2.2.3. Species Diversity

2.2.4. Length–Weight Relationship

2.2.5. Sex Ratio

2.3. Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using both descriptive and inferential statistical methods through SPSS Version 20 to ensure a comprehensive evaluation. Descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, percentage, and frequency distribution, were used to summarize key variables. Inferential statistical analyses were conducted to test hypotheses and establish relationships among variables. ANOVA was applied to assess significant differences across groups. Regression analyses were employed to examine the influence of independent variables on dependent variables, particularly in understanding factors affecting water conservation practices. The Chi-square (χ2) test was used to determine associations between categorical variables. This analytical approach ensured rigorous data interpretation, supporting evidence-based decision-making in the study.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fish Species Composition

A total of five fish species were identified during the present study in the Denkoro River. These species include Labeobarbus intermedius, Garra dembecha, Clarias gariepinus, Labeobarbus beso, and Oreochromis niloticus. All identified species belong to the class Actinopterygii (ray-finned fishes), encompassing three different orders and three families (Table 2). The family Cyprinidae was the most dominant, represented by Labeobarbus intermedius, Labeobarbus beso, and Garra dembecha, which were present at all sampling sites (Table 3). However, Clarias gariepinus was recorded only in the Buke and Wachu sampling sites, while Oreochromis niloticus was found exclusively at the Wachu site.

| Species name | Order | Family |

|---|---|---|

| L. intermedius | Cypriniformes | Cyprinidae |

| G. demebecha | Cypriniformes | Cyprinidae |

| L. beso | Cypriniformes | Cyprinidae |

| C. gariepinus | Siluriformes | Clariidae |

| O. niloticus | Cichliformes | Cichlidae |

| Species name | Sampling sites | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| KS | BS | WS | |

| L. intermedius | + | + | + |

| G. demebecha | + | + | + |

| L. beso | + | + | + |

| C. gariepinus | − | + | + |

| O. niloticus | − | − | + |

The fish species composition in the Denkoro River during the study period was relatively low compared to findings from other studies conducted in the Blue Nile and Tekeze drainage basins. For example, previous research identified 10 species in the Gerado and Derma Rivers [13], 23 species in the Beles and Gelegel Beles Rivers [14], 10 species in the Sanja and Angereb Rivers [15], 59 species in the Baro and Tekeze Basins [6], 17 species in the Beshilo, Dura, and Ardi Rivers [16], and 27 species in the Guang, Ayima, Gondwana, and Shinfa Rivers [17]. However, the results of the present study align more closely with studies conducted in the Awash Basin, where 6 species were identified in the Borkena and Upper Millie Rivers [18], 4 species in the Upper Millie [19], 5 species in the Lower Millie [20], and 6 species in the Terie River of the Blue Nile Basin [21].

Hydrological variations play a crucial role in shaping fish population patterns, particularly in habitats that are sensitive to changes in water flow [22–24]. Fluctuations in flow can significantly impact fish assemblages; for instance, high flows may destroy fish habitats and wash away fish eggs, while low flows during the dry season can trap fish in small, shallow pools, leading to increased stress, heightened vulnerability to predators, and higher fishing mortality [24]. The lower fish diversity observed in the Denkoro River might be attributed to limited fishing efficiency, as only a single set of gillnets and monofilaments were used, along with a restricted sampling period, one session during both the dry and wet seasons due to budget constraints. Additionally, the study sites were located within national parks inhabited by lions and other predators, which posed safety concerns and likely contributed to the limited sampling duration. An extended sampling period and improved sampling methods could potentially yield a higher number of identified fish species.

3.2. Fish Species Diversity

3.2.1. Fish Species Diversity During Wet and Dry Seasons

L. intermedius and L. beso were common in all the sampling sites in both seasons. G. demebecha was absent in KS and BS during the dry season. C. gariepinus was found both in BS and WS sites during the dry and wet seasons but absent in the KS site at both sampling periods. O. niloticus was not found in both KS and BS sites during the dry and wet seasons. The number of fish species was higher at the WS sampling site and lower at the KS sampling site (Table 4). Five species at WS and three species from KS sampling sites were recorded (Table 4). This variation in fish species diversity could be associated with the nature of the habitat. The higher fish species diversity in WS might be due to the presence of more rocks in the site which might be used for refuge by fishes and escape from predation and fishing mortality. The Denkoro River was dominated by the family Cyprinidae (Table 4).

| Fish species | Family | Sampling sites | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KS | BS | WS | |||||

| Dry | Wet | Dry | Wet | Dry | Wet | ||

| L. intermedius | Cyprinidae | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| G. demebecha | Cyprinidae | − | + | − | + | + | + |

| L. beso | Cyprinidae | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| C. gariepinus | Clariidae | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| O. niloticus | Cichlidae | − | − | − | − | + | − |

In the Denkoro River, abundance and fish species composition were higher in the dry season than the wet season. The dominant fish species of the river in the dry season was L. intermedius with a total number of 109 (50.9%). The dominant fish species in the wet season in the Denkoro River was L. beso with a total number of 75 (40.76%). The total fish species composition of the Denkoro River was more (5) in the dry season than the wet season (4). There might be several reasons for variation in abundance between wet and dry seasons. Variations in available nutrients and habitats, temperature, fishing effort, fish behavior, size and life history stages of fishes, and others might have contributed to the variation in abundance of the catches. Moreover, the water level [25] and turbidity of water may also affect abundance. The total number of fish specimens collected in the Denkoro River was more in the dry season (53.77%) than in the wet season (46.23%) (Table 5) similar to most of the findings reported in Ethiopian river fish diversity studies [6, 13, 15–21].

| Season | Sampling sites | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H′/N | WS | BS | KS | |

| Dry | H′ | 1.45 | 0.95 | 0.64 |

| N | 5 | 3 | 2 | |

| Wet | H′ | 1.33 | 1.18 | 0.93 |

| N | 4 | 4 | 3 | |

The Shannon diversity index (H′) was used to evaluate the species diversity of sampling sites. The Shannon diversity index explains both the variety and the relative abundance of fish species [26]. The species diversity in the Wachau site showed more diversity than Buke and Kernemariam sites in the dry and wet seasons (Table 6 and Figure 2). The H′ was higher in the WS sampling site with the values of (H′ = 1.45) followed by BS (H′ = 0.95) and KS (H′ = 0.64) in the dry season sampling period (Table 6). Similarly, H′ was higher in the WS sampling site with the values of (H′ = 1.33) followed by BS (H′ = 1.18) and KS (H′ = 0.93) in the wet season sampling period (Table 6).

| Fish species | Seasons | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry | Wet | Total | Percentage composition | Sig | |

| L. intermedius | 109 | 62 | 171 | 42.9 | p < 0.001∗∗∗ |

| G. demebecha | 18 | 22 | 40 | 0.05 | 0.527ns |

| C. gariepinus | 23 | 25 | 48 | 12.06 | 0.773ns |

| O. niloticus | 9 | 0 | 9 | 2.26 | 0.715ns |

| L. beso | 55 | 75 | 130 | 32.66 | 0.079ns |

| Total | 214 | 184 | 398 | 100 | |

- ∗∗∗(p < 0.001) (very highly significant).

- ns(p > 0.05) (nonsignificant).

3.3. Relative Abundance of Fishes

3.3.1. Relative Abundance of Fish During Wet and Dry Seasons

In the present study, a total of 398 fish specimens belonging to five species and 3 families were collected from the selected sampling sites of the Denkoro River. A higher number of fish (214) was collected during the dry season (Table 5).

The species composition of gillnet and monofilament catches both in dry and wet seasons was ranked based on the IRI value for different sampling sites (Tables 7 and 8). L. intermedius was the most abundant species during the study period constituting 42.9% of the total number of catches. L. beso, C. gariepinus, G. demebecha, and O. niloticus were found in the relative abundance of 32.66%, 12.06%, 10.05%, and 2.26%, respectively (Tables 7 and 8). L. intermedius was the most important fish species in the dry season in all sites (Tables 7 and 8). L. beso was very important in all sampling sites during the wet season.

| Sites | Fish | N | %N | W | %W | F | %F | IRI | %IRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KS | L. intermedius | 27 | 65.8 | 3510 | 78.2 | 3 | 75 | 10,800 | 88.5 |

| L. beso | 14 | 34.2 | 980 | 21.8 | 1 | 25 | 1400 | 11.5 | |

| G. demebecha | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| C. gariepinus | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| O. niloticus | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Total | 41 | 100 | 4490 | 100 | 4 | 100 | 12,200 | 100 | |

| BS | L. intermedius | 38 | 56.8 | 4940 | 61.6 | 4 | 57.2 | 6772.48 | 80.4 |

| L. beso | 20 | 29.8 | 1400 | 17.7 | 1 | 14.3 | 679.25 | 8.06 | |

| G. demebecha | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| C. gariepinus | 9 | 13.4 | 1665 | 20.7 | 2 | 28.5 | 971.85 | 11.54 | |

| O. niloticus | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Total | 67 | 100 | 8005 | 100 | 7 | 100 | 8423.58 | 100 | |

| WS | L. intermedius | 44 | 41.5 | 5720 | 50.3 | 5 | 33.33 | 3059.7 | 64.2 |

| L. beso | 21 | 19.8 | 1470 | 12.9 | 3 | 20 | 654 | 13.7 | |

| G. demebecha | 18 | 16.9 | 90 | 0.8 | 2 | 13.3 | 235.41 | 4.94 | |

| C. gariepinus | 14 | 13.3 | 2590 | 22.8 | 1 | 6.67 | 240.8 | 5.04 | |

| O. niloticus | 9 | 8.5 | 1485 | 13.2 | 4 | 26.7 | 579.39 | 12.15 | |

| Total | 106 | 100 | 11,355 | 100 | 15 | 100 | 4769.3 | 100 | |

| Sites | Fish | N | %N | W | %W | F | %F | IRI | % IRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KS | L. intermedius | 16 | 39.1 | 2080 | 58.3 | 2 | 50 | 4870 | 65.5 |

| L. beso | 21 | 51.2 | 1470 | 41.2 | 1 | 25 | 2310 | 31.06 | |

| G. demebecha | 4 | 9.70 | 20 | 0.5 | 1 | 25 | 255 | 3.44 | |

| C. gariepinus | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| O. niloticus | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Total | 41 | 100 | 3570 | 100 | 4 | 100 | 7435 | 100 | |

| BS | L. intermedius | 22 | 34.5 | 2860 | 46.02 | 3 | 42.8 | 3446.3 | 61.5 |

| L. beso | 29 | 45.3 | 2030 | 32.7 | 1 | 14.3 | 1115.4 | 19.9 | |

| G. demebecha | 6 | 9.3 | 30 | 0.48 | 1 | 14.3 | 139.8 | 2.44 | |

| C. gariepinus | 7 | 10.9 | 1295 | 20.8 | 2 | 28.6 | 906.62 | 16.16 | |

| O. niloticus | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Total | 64 | 100 | 6215 | 100 | 7 | 100 | 5608.12 | 100 | |

| WS | L. intermedius | 24 | 30.4 | 3120 | 37.77 | 4 | 40 | 2726.8 | 51.83 |

| L. beso | 25 | 31.6 | 1750 | 21.2 | 3 | 30 | 1584 | 30.13 | |

| G. demebecha | 12 | 15.2 | 60 | 0.73 | 2 | 20 | 318.6 | 6.05 | |

| C. gariepinus | 18 | 22.8 | 3330 | 40.3 | 1 | 10 | 631 | 11.99 | |

| O. niloticus | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Total | 79 | 100 | 8260 | 100 | 10 | 100 | 5260.4 | 100 | |

There might be several reasons for changes in abundance between wet and dry seasons. Variations in available nutrients and habitats, fishing effort, fish behavior, and size and life history stages of fishes might all contribute to variation in the abundance of the catches. Moreover, water level and turbidity of water may also affect abundance. Generally during this study, fish abundance in number was higher in the dry season than in the wet season. In the dry season, as the water level reduces, the density of the fish population becomes high in the pools because the fishes are trapped in these areas. As a result, more fishes are vulnerable to the gears, especially to the gill nets and monofilaments, hence the high catch. This could be one of the probable reasons for higher abundance in number during the dry season in this study. However, the abundance in number of fish was less in the wet season than in the dry season. This is probably due to the high level of water, which increased the velocity of the flow of water that affects the fish habitat, removing small fishes and eggs. It is also not a suitable condition to catch in that season.

3.4. Some Biological Aspects of Dominant Fish Species

3.4.1. Length–Weight Relationship

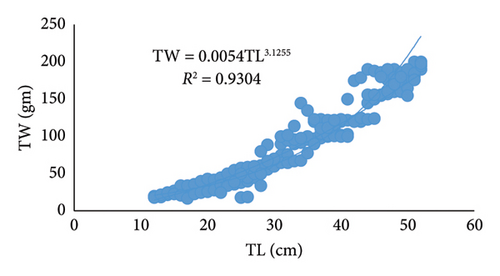

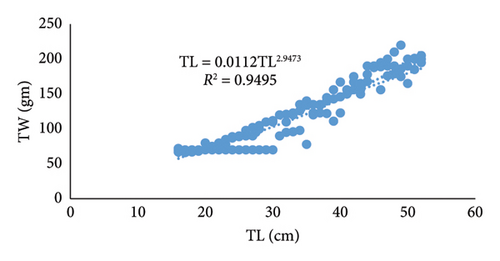

The relationship between the TL and TW for L. intermedius and L.beso was curvilinear and statistically significant (p < 0.05). The line fitted to the data was described best by the regression equation shown in Figures 2(a) and 2(b). In fishes, the regression coefficient b = 3 describes isometric growth. The value is precisely three if the fishes retain the same shape, and their specific gravity remains unchanged during their lifetime [27]. It is isometric growth, which means that the weight is increased according to the fish’s length. However, some fishes have a b value greater or less than 3; a condition of allometric growth [12]. From Figures 2(a) and 2(b), it can be established that L. intermedius and L. beso had isometric growth. This value was close to the values reported for some freshwater fish species by Tessema [18] in Borkena and Mille Rivers, Anteneh [28] in Dirma and Megech Rivers, Getahun [29] in the Rib River, Omer [30] in the head of the Blue Nile River, and Tesfaye [15] in Angereb and Sanja Rivers.

3.4.2. Sex Ratio

Of the 398 fish collected during the study period, 35 (8.79%) were unsexed and excluded from the sex ratio analysis. The remaining 363 specimens were sexed, comprising 201 females (55.3%) and 162 males (44.6%), resulting in an overall female-to-male sex ratio of 1.21:1. Statistical analysis (Chi-square, p < 0.05) indicated a significantly higher number of females than males, except for C. gariepinus and O. niloticus (Table 9).

| Species | F | M | Sex ratio (F:M) | χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. intermedius | 119 | 43 | 2.76:1 | 35.65 | p < 0.001∗∗∗ |

| L. beso | 87 | 33 | 2.63:1 | 24.3 | p < 0.001∗∗∗ |

| G. demebecha | 23 | 9 | 2.55:1 | 6.12 | 0.013∗ |

| C. gariepinus | 24 | 18 | 1.33:1 | 0.857 | 0.355ns |

| O. niloticus | 5 | 2 | 2.5:1 | 1.28 | 0.257ns |

- ∗significant (p < 0.05).

- ∗∗∗Very highly significant (p < 0.001).

- nsmeans nonsignificant (p > 0.05).

The imbalance of the female to male ratio was most probably related to different biological mechanisms such as differential maturity rates, differential mortality rates, and differential migratory rates between the male and female sexes [31].

4. Conclusion and Recommendations

Five fish species were recorded from the Denkoro River. The diversity of the fish fauna of the Denkoro River is dominated by the cyprinidae fish family where L. intermedius, L. beso, and C. gariepinus were the most dominant fish species in number and total biomass during the study periods. The result of this study will be used as baseline data for BSWNP and other interested institute and individuals that have great interest in biodiversity.

Therefore, further research on fish species and unexplored aspects of their biology, such as food and feeding ecology, are essential for the sustainable conservation and utilization of the fish resources in the Denkoro River.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Assefa Tessema Tecklie (PhD) is working in Wollo University as a lecturer and researcher in fisheries, wetlands, and aquatic science area. He is also working as an officer for aquatic and other natural resource management in the Abay Awash Basins Institute of Wollo University. Wondoson Mekonen Workneh is a biology teacher in the Densa Secondary School. He is a model teacher in the school and has more interest on investigation of fish species in rivers and other hotspot areas.

Author Contributions

The data collection, analysis, and draft paper were prepared by the Wondoson Mekonen Workneh. The section of the journal and preparation of the manuscript based on the publisher guideline and submission of the manuscript were performed by Assefa Tessema Tecklie. The high school teacher got training on how to identify fish species, and he got support from his advisor for identification.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the BSWNP administration bodies, scouts, and the local fishermen who supported them during data collection of the study.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the findings of this study can be obtained based on a request from the authors.