The Development of an Employment Anxiety Scale for Chinese College Graduates

Abstract

This study aims to develop an employment anxiety scale for Chinese college graduates, providing a tool for subsequent research on employment anxiety in China. The exploratory factor analysis (EFA) identified two factors: “Cognitive Expectations” and “Somatic Symptoms.” The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results suggested that retaining 14 key items led to a good model fit, confirming the EFA results. The internal consistency reliability of the scale was 0.9254. Correlation analysis between the self-constructed scale and the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory indicated high validity of the self-constructed scale. Graduates’ anxiety scale scores varied by different sociodemographic characteristics. Female graduates, undergraduates, and graduates from regular colleges scored higher on the anxiety scale. The self-constructed employment anxiety scale for college graduates demonstrated good reliability and validity, making it a suitable tool for measuring employment anxiety among college graduates. Furthermore, it holds significant potential for informing targeted interventions by universities to address key aspects of employment anxiety and for evaluating the effectiveness of employment-related policies, ultimately supporting graduate well-being and improving outcomes in the transition to the workforce.

1. Introduction

In the current global economic environment, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted the job market, particularly for college graduates. Reports indicate that the number of college graduates in China reached a record high of 12.22 million in 2025, placing immense pressure on the job market [1]. The most recent data from November 2024 showed an unemployment rate of 16.1% for the 16- to 24-year age group [2]. Long-term survey results indicate that the proportion of formal employment among Chinese college graduates has reached a new low, the rate of further education has continued to rise, the employment implementation rate has declined, and the rate of those waiting for employment has rebounded [3]. All these data indicate that college graduates in China are currently facing significant difficulties and challenges in finding employment. Furthermore, based on estimates of China’s birth population and university enrollment ratio in recent years [4], the number of college graduates in China will remain above 10 million annually for at least the next decade. Combined with the yearly accumulation of unemployed graduates, the employment pressure is evident.

In response to this challenge, the Chinese government has implemented several policy measures, including the launch of a 24/7 online campus recruitment service platform, extending the registration and settlement time limits for college graduates, and expanding the enrollment scale of master’s and undergraduate programs to stabilize employment expectations [5]. In some regions, such as Shanghai, subsidies of RMB 2000 are provided to units that sign contracts of at least 1 year with college graduates [6]. To address the employment issues of the 2024 college graduates, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, the Ministry of Education, and the Ministry of Finance jointly issued a notice on promoting employment and entrepreneurship among college graduates and other young people [7]. Additionally, the Ministry of Education has launched a “100-day sprint” action for the 2024 college graduates, aiming to promote high-quality and full employment through six major actions, including the “Employment Promotion Week” [8].

However, despite these policy supports and educational interventions, employment anxiety among college graduates remains significant. Employment anxiety refers to the tense, uneasy, intense, and persistent emotional experience individuals, especially first-time job-seeking college students, face when making career choices. A certain degree of anxiety can facilitate successful employment for graduates, but excessive anxiety may lead to psychological disorders, thus hindering successful employment [9]. Although there are no large-scale national surveys on employment anxiety among college graduates, the “China National Mental Health Development Report (2021-2022)” shows that only half of college students are free from anxiety risk (54.72%). Additionally, the survey indicates that 50.44% of college students plan to pursue further studies, and those intending to do so exhibit significantly higher anxiety risks than those who do not plan to continue their education [10]. Reports directly investigating employment anxiety among college graduates are rare and mostly focus on small-scale surveys in individual schools or regions, which lack national representation but still reflect the current state of graduate employment anxiety to some extent. For example, a survey conducted in Guangdong Province during the pandemic found that the employment anxiety level of college graduates was moderately high [11]. Another survey of 267 undergraduate graduates at a medical college in Xinjiang indicated that 46.40% experienced employment anxiety [12]. These findings underscore the significance of addressing employment anxiety among college graduates and the need for further attention to this issue.

Currently, there is limited research in China on the construction of scales for measuring employment anxiety. From the literature review, it appears that studies on the development of employment anxiety scales in China mostly began after 2000, which was attributed to the sharp increase in employment pressure caused by the large-scale expansion of higher education in China. However, these scales were developed relatively early and are mostly regional studies with small sample sizes [9, 13–16]. Furthermore, some employment anxiety scales are not suitable for China’s rapidly developing economic environment, employment landscape, and the large population of college graduates [17, 18]. Additionally, other foreign scales may not be entirely suitable for the domestic context and often measure general anxiety or serve as medical diagnostic tools, lacking specificity for employment anxiety among college graduates [19–23].

In contrast, the scale we propose has several key advantages: First, it is specifically designed to measure employment anxiety among Chinese college graduates, making it more culturally and contextually relevant. Second, our scale refines the multiple dimensions of employment anxiety addressed by previous scales and is shorter in length, thereby reducing the burden on respondents while maintaining accuracy in measurement. Finally, our scale is based on a nationally representative sample, ensuring its relevance and applicability across the diverse socioeconomic landscape of China.

To address the psychological challenges faced by Chinese college graduates, this study aims to develop a specialized employment anxiety scale tailored to their unique experiences. By accurately measuring employment anxiety, the scale will establish a standard for assessing the psychological pressures related to career transitions. It will serve as a valuable tool for universities, helping them guide graduates in their career development and providing a basis for psychological counseling to support their mental well-being.

Given the significance of recent government initiatives aimed at alleviating employment pressure, our proposed scale also holds an important role in evaluating the effectiveness of these policies. By measuring employment anxiety both before and after the implementation of these measures, the scale will provide insights into how well these policies have mitigated the employment-related stress among graduates, offering crucial data to inform future policy decisions and adjustments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Introduction

The purpose of the Survey of Employment Status of College Graduates in China is to promptly understand graduates’ employment intentions and status. This monthly survey randomly selects respondents from all college graduates of the current year, using telephone. The survey for this study was conducted in February 2024, a time when most graduates had not yet left school and many were actively seeking employment. The survey covers detailed information on personal, social, economic, employment, career, and salary-related topics. This study will utilize this survey to test the employment anxiety questionnaire for graduates.

2.2. Item Generation

Based on the best practices for scale construction from existing literature reviews [24] and measurements of employment anxiety among college graduates [9, 13–16], this study selected 32 graduates from the 2024 cohort of Renmin University of China for semistructured questionnaire case interviews. The semistructured questionnaire was revised after consulting two research experts—one specializing in college student employment research and the other in college student psychological behavior research. The main content collected included (1) basic student information, such as age, gender, major, and education level; (2) perceptions or experiences of future graduation anxiety, employment pressure, and behaviors; (3) psychological, emotional, or physiological reactions caused by employment pressure; and (4) other reasons for concern and anxiety about future employment. The 32 graduates were evenly distributed, with 16 males and 16 females, 16 from natural sciences and 16 from humanities, and 16 undergraduates and 16 postgraduates. All interview processes were recorded. The transcripts were cross-checked with the recordings, and two coders independently extracted key information and themes from the interviews, resulting in 34 employment anxiety-related themes. Based on these themes, 34 questionnaire items were developed. These 34 items were then reviewed by an expert panel consisting of five members from the fields of college student employment, psychology, sociology, statistics, and psychiatry. The panel conducted two rounds of independent evaluations on the applicability, accuracy, and interpretability of the items, ultimately retaining 30 items based on acceptance, objections, or suggestions for modification.

2.3. Data Collection

This study employed a standard survey experimental design and was conducted by the National Survey Research Center at Renmin University of China. The sample was randomly drawn from the registration database of Chinese college graduates for the current year. The sampling process involved randomly selecting schools while considering two factors: education level and major. The final sample size was 12,196 individuals.

To compare the tested anxiety scale with three different benchmark anxiety scales, namely, the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale [20], the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [22], and the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [25]—all selected participants were required to complete the tested anxiety scale, but each respondent was randomly assigned to answer only one of the benchmark anxiety scales. This design allowed for a comparative analysis of the tested scale against these established benchmarks in a way that minimizes potential bias. The selection of these three benchmark scales was based on their relevance and established validity in measuring anxiety. The SAS is widely used to assess general anxiety symptoms and is known for its strong reliability and validity across various populations, making it an appropriate tool for comparing general anxiety levels. The HADS, specifically designed to measure both anxiety and depression, was chosen due to the overlap between emotional distress and employment anxiety, which allowed us to explore how our scale captures anxiety in the broader context of psychological distress. Finally, the STAI differentiates between state anxiety (temporary anxiety) and trait anxiety (chronic anxiety), providing a useful framework for comparing the transient versus enduring nature of employment anxiety, a key focus of our study. By using these three well-established scales, we were able to ensure the robustness and comprehensiveness of the comparison, strengthening the validity of our findings.

The telephone survey was conducted using a distributed telephone survey system developed by the National Survey Research Center at Renmin University of China. Distributed telephone survey systems utilize internet-based telephony to conduct surveys. Unlike traditional systems based on landline phone numbers, interviewers do not need to work in a centralized survey room. There is no limit to the number of survey stations, and interviewers can register, participate in online training, pass exams, and log into the system to dial preloaded phone numbers, as long as they have internet access. This greatly increases efficiency and reduces survey costs. Furthermore, interviewers cannot see the actual phone numbers being dialed, which helps protect the privacy of respondents. After obtaining oral consent from the respondent, the system can record the conversation. A recording auditor checks whether the interviewers are adhering to standardized interview protocols and monitors the quality of the questionnaires. Each selected phone number was called up to three times. Numbers that were successfully contacted or explicitly refused were not called again, and there was a minimum interval of one day between each call attempt.

All respondents agreed to participate in this survey and provided verbal informed consent before the formal telephone interview. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Survey Research Center at Renmin University of China, adhering to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments (NSRCSE2024010403).

2.4. Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA 16.0 software. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the sample size and percentage composition of sample characteristics. The discriminant validity of the scale was assessed using Pearson correlation coefficients between the score of each item and the total scale score. Items with Pearson correlation coefficients less than 0.4 were deleted, totaling 3 items, specifically items 8, 9, and 25. The discrimination index analysis involved ranking the total scores of the scale from high to low, with the top 27% as the high score group and the bottom 27% as the low score group. A t-test was conducted to compare the mean scores of all 27 items between the two groups. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to analyze the underlying factor structure of the scale and to remove potentially problematic items. A total of three EFA were conducted in this study. The first EFA revealed that items with uniqueness values exceeding 0.6 were deleted, including Items 11 and 13. Additionally, after extracting two factors, items with a factor loading difference of less than 0.15 between the two factors were removed. As a result, 12 items were deleted in the first EFA: Items 1, 3, 9, 11, 13, 16, 17, 21, 26, 28, 29, and 30. In the second EFA, Item 14 was also deleted due to a factor loading difference of less than 0.15 between the two factors. The third EFA was conducted based on the remaining 14 items. To determine the number of factors in the EFA, this study conducted a parallel analysis. The “paran” command in Stata was used to generate random data through 100 iterations, and the results of the actual data were compared with those of the random data to validate the preliminary factor determination. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using structural equation modeling (SEM) to validate the two factors extracted by the EFA. The model fit was evaluated using indices such as goodness of fit, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The reliability of the scale was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Criterion-related validity was assessed by calculating Pearson correlation coefficients between the total score and subdimension scores of the self-constructed scale and those of the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and STAI. Statistical significance level α = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

The demographic distribution of the sample reflected a diverse range of educational backgrounds, academic disciplines, and types of institutions, as shown in Table 1. Among the 12,196 valid samples in this survey, males slightly outnumbered females, accounting for 51.58% and 48.42%, respectively. Students with associate, bachelor’s, and graduate degrees made up 46.15%, 42.72%, and 11.13% of the sample, respectively, with a higher proportion of associate and bachelor’s degree holders and fewer graduate students. From a disciplinary perspective, natural sciences majors were significantly more prevalent than humanities and social sciences majors, accounting for 74.38% and 25.62%, respectively. In terms of school type, elite universities, regular universities, and vocational colleges accounted for 23.41%, 33.21%, and 43.38%, respectively.

| Variable | Group | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 6291 | 51.58 |

| Female | 5905 | 48.42 | |

| Education level | Associate | 5628 | 46.15 |

| Bachelor’s | 5210 | 42.72 | |

| Graduate | 1358 | 11.13 | |

| Academic discipline | Natural sciences | 9071 | 74.38 |

| Humanities and social sciences | 3125 | 25.62 | |

| School type | Elite universities | 2855 | 23.41 |

| Regular universities | 4050 | 33.21 | |

| Vocational colleges | 5291 | 43.38 | |

3.2. Item Analysis

The discriminant validity of the self-constructed anxiety scale was assessed to ensure the items accurately measured distinct dimensions of anxiety. Among the 30 items in the self-constructed anxiety scale, 27 items had a discriminant validity above 0.5. Specifically, 13 items had values above 0.7, 12 items had values between 0.6 and 0.7, and only 2 items had values between 0.5 and 0.6. Three items had Pearson correlation coefficients with absolute values less than 0.4, indicating that these items did not sufficiently correlate with the total scale score and were therefore not contributing effectively to measuring the intended construct of anxiety, so these three items were excluded (Items 8, 19, and 25 in Table 2).

| Item | Correlation coefficients | t value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The thought of employment makes me feel very irritable | 0.7821 | −1.2e + 02 | < 0.001 |

| 2. Due to employment pressure, I have lost my appetite | 0.6893 | −76.7813 | < 0.001 |

| 3. Hearing others talk about job hunting makes me anxious | 0.7948 | −1.2e + 02 | < 0.001 |

| 4. Thinking about my future after graduation makes me feel very confused | 0.7674 | −1.2e + 02 | < 0.001 |

| 5. The thought of employment makes it difficult for me to concentrate on other tasks | 0.7726 | −1.1e + 02 | < 0.001 |

| 6. Employment pressure has affected my sleep | 0.6990 | −86.2513 | < 0.001 |

| 7. I have become more irritable than before due to employment pressure | 0.6936 | −80.1379 | < 0.001 |

| 8. Despite the pressure of graduation, I still eat and sleep as usual | −0.0108 | 1.6544 | 0.0981 |

| 9. I constantly worry about graduates not finding jobs, which makes me very tense | 0.7905 | −1.3e + 02 | < 0.001 |

| 10. Due to employment pressure, I have developed physical problems like stomach pain, constipation, and mouth ulcers | 0.6537 | −71.3607 | < 0.001 |

| 11. I really want to stay in school for a few more years and not start working now | 0.5024 | −52.0264 | < 0.001 |

| 12. I still don’t have a clear idea of what I want to do | 0.6807 | −84.7048 | < 0.001 |

| 13. I feel that my major is not competitive in the job market | 0.5417 | −57.3552 | < 0.001 |

| 14. I get anxious whenever I hear media reports about the employment situation of college graduates | 0.7614 | −1.1e + 02 | < 0.001 |

| 15. I feel I lack the necessary job-hunting skills and will perform poorly in interviews | 0.7230 | −97.0076 | < 0.001 |

| 16. I worry about not having family and social connections when looking for a job | 0.6971 | −86.0060 | < 0.001 |

| 17. I am concerned that my employment situation will not meet my parents’ expectations | 0.6958 | −92.1505 | < 0.001 |

| 18. I feel that I did not learn the necessary knowledge and skills for work during school | 0.6421 | −74.8151 | < 0.001 |

| 19. As long as I can find a job after graduation, I have no high demands | −0.3613 | 34.5695 | < 0.001 |

| 20. I worry that my abilities will not meet the employer’s requirements | 0.7140 | −95.3619 | < 0.001 |

| 21. I worry about being the only one among my peers who cannot find a job | 0.7431 | −1.1e + 02 | < 0.001 |

| 22. I feel that I am not ready to enter the workforce after graduation | 0.6922 | −86.3127 | < 0.001 |

| 23. I worry about being asked questions in interviews that I cannot answer | 0.6856 | −88.6257 | < 0.001 |

| 24. I worry that the job I eventually find will not suit me | 0.6756 | −85.8483 | < 0.001 |

| 25. Despite the pressure of graduation, I remain very calm | 0.1377 | −12.4976 | < 0.001 |

| 26. I worry about being mocked if my post-graduation plans are not ideal | 0.7111 | −90.4583 | < 0.001 |

| 27. I do not have a clear idea of my career interests | 0.6647 | −79.1152 | < 0.001 |

| 28. I feel anxious because I do not understand job application techniques | 0.7680 | −1.1e + 02 | < 0.001 |

| 29. The thought of attending job fairs scares me | 0.7359 | −95.8958 | < 0.001 |

| 30. I feel pessimistic and disappointed about my employment prospects | 0.7507 | −1.0e + 02 | < 0.001 |

As shown in Table 2, the t-test results for all 27 items indicate that the t-values are large and the p values are all < 0.001, demonstrating that the discrimination indices meet the required standards. Therefore, all 27 items are retained.

3.3. EFA

To evaluate the suitability of the data for factor analysis, we conducted Bartlett’s test of sphericity and assessed the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy. The results showed that the data were highly appropriate for factor analysis. Specifically, the Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded a chi-square statistic of 2.08e + 05 with a p value of less than 0.001. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.982, indicating that the data were suitable for factor analysis.

To identify the underlying structure of the anxiety scale, we performed an EFA on the 27 remaining items. The preliminary EFA result shows that there are two factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, which together explain 56.31% of the total variance. Based on the loadings of each question on the two factors and the core experiences of anxiety, Factor 1 can be summarized as “Cognitive Expectations,” and Factor 2 can be summarized as “Somatic Symptoms.” However, the EFA also revealed that Items 11 and 13 had uniqueness exceeding 0.6, indicating that these two items are difficult to explain through the two factors. Moreover, there were 11 items with a factor loading difference of less than 0.15 between the two factors, specifically Items 1, 3, 9, 13, 16, 17, 21, 26, 28, 29, and 30. After removing these 12 items, a second factor analysis was conducted, revealing that the difference in factor loadings for Item 14 was still less than 0.15 between the two factors. Item 14 was subsequently removed, and a third factor analysis was performed with the remaining 14 items. The loadings of the 14 variables on these two factors are presented in Table 3.

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15. I feel I lack the necessary job-hunting skills and will perform poorly in interviews | 0.7542 | 0.2474 | 0.5068 |

| 23. I worry about being asked questions in interviews that I cannot answer | 0.7318 | 0.2136 | 0.5182 |

| 20. I worry that my abilities will not meet the employer’s requirements | 0.7229 | 0.2783 | 0.4446 |

| 12. I still don’t have a clear idea of what I want to do | 0.7216 | 0.2581 | 0.4635 |

| 22. I feel that I am not ready to enter the workforce after graduation | 0.7088 | 0.2594 | 0.4494 |

| 4. Thinking about my future after graduation makes me feel very confused | 0.7016 | 0.3657 | 0.3359 |

| 27. I do not have a clear idea of my career interests | 0.6866 | 0.2763 | 0.4103 |

| 24. I worry that the job I eventually find will not suit me | 0.6537 | 0.2924 | 0.3613 |

| 18. I feel that I did not learn the necessary knowledge and skills for work during school | 0.6013 | 0.3151 | 0.2862 |

| 5. The thought of employment makes it difficult for me to concentrate on other tasks | 0.4218 | 0.7021 | −0.2803 |

| 7. I have become more irritable than before due to employment pressure | 0.2543 | 0.7874 | −0.5331 |

| 6. Employment pressure has affected my sleep | 0.2359 | 0.8218 | −0.5859 |

| 2. Due to employment pressure, I have lost my appetite | 0.2084 | 0.8381 | −0.6297 |

| 10. Due to employment pressure, I have developed physical problems like stomach pain, constipation, and mouth ulcers | 0.1728 | 0.8308 | −0.658 |

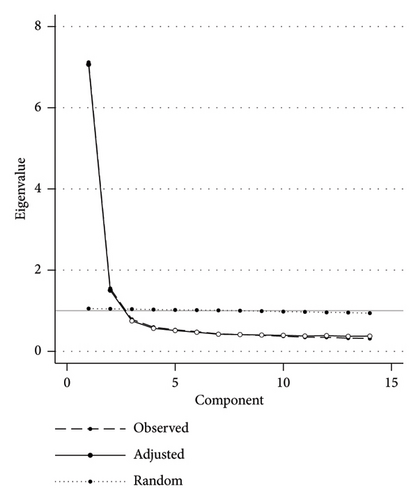

To determine the number of factors in the EFA, a parallel analysis was conducted. The results showed that the eigenvalues of the first two factors (7.0686 and 1.5107) were higher than the 95th percentile eigenvalues of the random data (1.0503 and 1.0389), indicating that these two factors should be retained. This is consistent with the preliminary estimation based on the Kaiser criterion. The final results of the parallel analysis are shown in Figure 1.

3.4. CFA

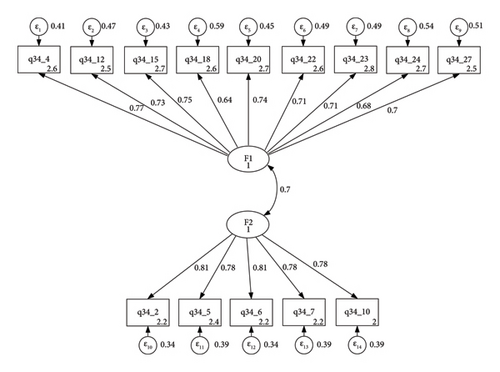

To assess the goodness of fit for the two-factor model derived from the EFA, we conducted a CFA on the final 14 items, as shown in Figure 2. The CFA results yielded strong fit indices, suggesting that the two-factor model adequately represents the data. Specifically, the RMSEA of 0.071, which is less than the commonly accepted threshold of 0.08, a CFI of 0.951, exceeding the commonly accepted threshold of 0.9, and an SRMR) of 0.041, below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.05. These indices suggest that the two-factor model provides a good fit to the data. This model, with 14 items, demonstrated good fit indices, confirming the scale’s strong structural validity.

3.5. Reliability Analysis

The reliability analysis of the self-constructed anxiety scale indicated that the overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.9254. The coefficients for the two subdimensions, Cognitive Expectations and Somatic Symptoms, were 0.9041 and 0.8942, respectively, both exceeding 0.8. This demonstrates that the overall scale and its two dimensions have high reliability.

3.6. Criterion-Related Validity Analysis

To further assess the criterion-related validity of the self-constructed anxiety scale, a correlation analysis was conducted between the total score and the two subdimensions of the self-constructed anxiety scale and three benchmark anxiety scales. The results revealed that the correlation coefficients between the total score and the scores of each subdimension of the self-constructed scale all exceeded 0.8. Furthermore, the total score and the two subdimensions of the self-constructed scale showed the strongest correlations with the STAI. Notably, the correlation between the Somatic Symptoms subdimension of the self-constructed scale and the State Anxiety subscale of the STAI was the highest, reaching 0.6022. Table 4 presents the detailed results, demonstrating that the self-constructed anxiety scale has good construct validity and overall validity.

| Scale | Total score | Cognitive expectations | Somatic symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive expectations | 0.9482 | — | |

| Somatic symptoms | 0.8480 | 0.6358 | — |

| Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) | 0.4795 | 0.3390 | 0.5985 |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | 0.5304 | 0.4270 | 0.5758 |

| State Anxiety Inventory (STAI1) | 0.5961 | 0.5088 | 0.6022 |

| Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI2) | 0.5859 | 0.5181 | 0.5620 |

3.7. Comparison of Employment Anxiety Among College Graduates With Different Characteristics

To examine the influence of demographic factors on anxiety levels, we analyzed the differences in anxiety scores across various groups, including gender, educational level, academic discipline, and type of institution. The results revealed notable differences in anxiety levels based on gender, educational level, and institution type. Specifically, as shown in Table 5, female college graduates have higher scores than males on the total scale, Cognitive Expectations dimension, and Somatic Symptoms dimension, with statistically significant gender differences (all p < 0.001). Regarding educational level, bachelor degree students have the highest anxiety scores on the total scale, followed by associate degree students, with graduate students having the lowest anxiety scores (all p < 0.001). In terms of different majors, there is no statistically significant difference in total scale and subdimensions scores (p > 0.05). Regarding different types of institutions, graduates from regular universities have the highest total anxiety scores, followed by vocational colleges, with elite university graduates having the lowest anxiety scores (all p < 0.001).

| Variable | Group | Cognitive expectations () | Somatic symptoms () | Total score () |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 25.81 ± 0.10 | 11.72 ± 0.06 | 37.53 ± 0.14 |

| Female | 27.64 ± 0.10∗∗∗ | 12.26 ± 0.06∗∗∗ | 39.90 ± 0.14∗∗∗ | |

| Education level | Associate | 26.52 ± 0.10 | 12.26 ± 0.06 | 38.78 ± 0.15 |

| Bachelor’s | 27.41 ± 0.10 | 11.78 ± 0.06 | 39.18 ± 0.15 | |

| Graduate | 24.70 ± 0.20∗∗∗ | 11.64 ± 0.12∗∗∗ | 36.34 ± 0.29∗∗∗ | |

| Academic discipline | Natural sciences | 26.65 ± 0.08 | 11.99 ± 0.05 | 38.64 ± 0.12 |

| Humanities and social sciences | 26.85 ± 0.13 | 11.95 ± 0.08 | 38.80 ± 0.19 | |

| School type | Elite universities | 26.48 ± 0.14 | 11.41 ± 0.08 | 37.89 ± 0.20 |

| Regular universities | 27.12 ± 0.12 | 12.05 ± 0.07 | 39.17 ± 0.17 | |

| Vocational colleges | 26.49 ± 0.11∗∗∗ | 12.24 ± 0.06∗∗∗ | 38.73 ± 0.16∗∗∗ | |

- ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

In recent years, the global economic slowdown, the expansion of Chinese higher education, and the impact of the 3-year COVID-19 pandemic have made the employment situation for Chinese college graduates more severe. Consequently, employment pressure and anxiety among college graduates have been rising. To better understand the employment anxiety experienced by Chinese college graduates, it is urgent to develop relevant anxiety scales. This study, based on the Survey of Employment Status of College Graduates in China, adopted a randomized experimental design and utilized a large-scale random sample of Chinese college graduates to preliminarily develop an employment anxiety scale for Chinese college graduates. The significance of this study is both substantial and timely. First, the scale can serve as a tool for regular monitoring of graduates’ anxiety levels. By administering the scale at different points in time—such as during their final year of study, shortly after graduation, and at several intervals during their early career years—universities can track how anxiety levels change in relation to the job search process, employment stability, and career transitions. This would allow institutions to identify patterns of rising anxiety and intervene proactively to support students and graduates who may be at risk of high psychological distress. Second, universities can use the scale to design targeted interventions addressing key aspects of employment anxiety. For example, items on job-hunting skills and career uncertainty (e.g., “I feel I lack the necessary job-hunting skills” or “I still don’t have a clear idea of what I want to do”) could lead to career counseling and skills workshops. Additionally, items reflecting stress-related symptoms (e.g., “Employment pressure has affected my sleep” or “The thought of employment makes it difficult for me to concentrate”) suggest the need for stress management programs. These interventions would help universities better support graduates during their transition to the workforce. Third, policymakers can leverage the scale to evaluate the effectiveness of employment-related policies. By assessing graduates’ anxiety levels before and after the implementation of specific policies—such as subsidies for employers, career placement programs, or entrepreneurship support measures—policymakers can gauge whether these interventions are effectively reducing psychological pressures related to employment. This data-driven approach would help inform future policy decisions and provide evidence of the success or areas for improvement in current strategies. Ultimately, the scale holds significant potential for enhancing both individual and institutional support systems, thereby reducing employment-related anxiety and improving overall graduate well-being in a rapidly changing job market.

This paper combines qualitative and quantitative research methods, employing various statistical models to establish the employment anxiety scale for Chinese college graduates, and conducted reliability and validity verification and analysis. When establishing the initial item pool for the scale, the authors referred to relevant domestic and international literature [9, 13–16], gathered detailed feedback from a sufficiently large sample of graduates, and extracted and organized this information. Additionally, this study utilized expert consultation to analyze the content of the scale items. The item analysis of the scale calculated classical discrimination and differentiation indices, and based on the discrimination indices, three items with low relevance were removed.

Before the EFA, Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the KMO measure indicated that the data were suitable for factor analysis. The EFA extracted two factors based on the criterion of eigenvalues greater than 1, representing the cognitive expectations and somatic symptoms of employment anxiety, consistent with the diagnostic definition of anxiety [26]. It is worth noting that the two factors, Cognitive Expectations and Somatic Symptoms, do not encompass all the dimensions of anxiety, but they align with the initial design concept of the scale, which aimed to simplify and include the core aspects of employment anxiety while remaining consistent with the conventional definition of anxiety. All item loadings on these two factors exceeded 0.5, and the two factors together explained 56.31% of the total variance, indicating a good factor analysis result. The CFA further validated the EFA results, and the final model with 14 items showed good fit.

The reliability analysis of the scale using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient revealed an overall value of 0.9254, indicating that the scale’s reliability is significantly higher than the average psychological scale [27–29]. Innovatively, the study also tested the scale against three classic anxiety benchmark questionnaires within a large sample population, demonstrating good external validity.

This study compared the anxiety scores of different genders, education levels, majors, and types of schools using the constructed employment anxiety scale. The results showed that female graduates exhibited higher anxiety levels than males, consistent with other studies [9] and the higher incidence of psychological disorders in women [30, 31], possibly due to greater sensitivity and gender bias in the job market. Bachelor degree students and graduates from regular universities had the highest anxiety scores, while graduate students and elite university graduates had the lowest, possibly due to lower employment rates for bachelor degree students compared to graduates from elite universities [32].

Compared to other domestic employment anxiety scales for college graduates, this study has several advantages: (1) The scale construction referenced relevant literature extensively [9, 13–18, 33], ensuring a more standardized and rigorous process. (2) The sample size for the scale test was large, facilitated by the strong data collection capabilities of the research institution, making this scale construction with over 10,000 participants rare in academic research. (3) The sample selection aimed to represent Chinese college graduates as broadly as possible, using random sampling principles to avoid concentration in specific schools or regions. (4) The study utilized three benchmark scales and a randomized experimental design to collect data, minimizing respondent selection bias and obtaining reliable external validation results.

However, the study has some limitations: (1) Limited by the Ministry of Education’s graduate registration information, it could not analyze more demographic characteristics of graduates, but the sample is representative in terms of gender, education level, major, and type of school. Based on the periodic Survey of Employment Status of College Graduates in China, future rounds of the survey could include additional sociodemographic variables, such as academic performance, parents’ education levels, and family income. This would allow for a deeper exploration of factors that may influence employment anxiety among college graduates, as well as the relationship between employment anxiety and employment rates. (2) Data collection was conducted via telephone surveys, which may introduce social desirability bias [34, 35]; future research should consider using online surveys to verify the anxiety scale. (3) The study did not perform a test–retest reliability analysis, which should be included in future research. In addition, the next two rounds of the survey could involve a retest of reliability using the new 14-item scale, along with further validity assessments by retaining only the STAI scale. This would allow for a more comprehensive validation of the scale on a larger population of college graduates.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study used qualitative methods for initial questionnaire design and quantitative methods to develop a preliminary employment anxiety scale for Chinese college graduates based on a large-scale probability sample. The preliminary validation showed that the scale has good reliability and validity, meeting basic psychometric requirements, and can be used for preliminary measurement and assessment of employment anxiety among Chinese college graduates. Additionally, it has the potential to inform targeted interventions by universities to address key aspects of employment anxiety and to evaluate the effectiveness of employment-related policies, thereby supporting graduates’ transition to the workforce and enhancing overall well-being.

Ethics Statement

All respondents agreed to participate in this survey and provided verbal informed consent before the formal telephone interview. The study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of National Survey Research Center at Renmin University of China (NSRCSE2024010403). The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, including its subsequent revisions.

Disclosure

The funder had no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

The formal data analysis, oversight of the study methodology, and first drafting was completed by Weidong Wang. Yisong Hu was the corresponding author who contributed to the entirety of the investigation, supervision, and review.

Funding

This research was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities and the Research Funds of Renmin University of China (Project number: 10XNN002).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Survey Research Center at Renmin University of China for conducting the data collection, the respondents who participated in the survey for their cooperation with us, and all volunteers and staff involved in this study.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Due to the confidential nature of the data used in this study, we are unable to share the dataset publicly. However, data may be made available upon request to qualified researchers under appropriate confidentiality agreements.