Altruism, Political Trust, and Their Influence on COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic reconfirmed the fact that not everyone is motivated to receive vaccination. In fact, many showed hostility to COVID-19 vaccination, raising public health concerns. Thus, this study explores the factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination intentions, focusing on altruism and political trust and arguing that they are positively associated with individuals’ vaccination intentions. More importantly, this study examines whether political trust serves as a moderator between altruism and vaccination intentions. We argue that political trust strengthens the positive relationship between altruism and vaccination intentions. We relied on the 2021 Korean General Social Survey, which yielded a sample of 306. Employing an ordered logit regression, we found that individuals’ levels of altruism are positively associated with their vaccination intentions. Although the individual level of political trust was not statistically significantly linked to vaccination intentions, it was proven to strengthen the positive link between individuals’ levels of altruism and their vaccination intentions. The results suggest the importance and need to cultivate individuals’ altruism as well as their political trust.

1. Introduction

Emerging in late 2019, COVID-19 has infected and upended the lives of hundreds of millions of people across countries [1]. As of October 2023, the World Health Organization Coronavirus Dashboard estimates that the virus has caused over 6.9 million deaths and infected over 767 million people [2]. Vaccines have been known to effectively mitigate infectious outbreaks such as COVID-19 [3, 4]. Fortunately, they became available to the public through an unprecedented combination of speed, innovative breakthroughs, government assistance, and collaboration, with over 13 billion doses administered as of October 2023 [2]. Still, administering vaccines has demonstrated the gap between governments’ efforts to increase vaccination rates and some individuals’ adamantly opposing vaccination for ideological, religious, and personal health reasons [5]. Given that vaccines produce salutary effects, such as reduced hospitalizations and fatalities [6, 7], yet have been subject to intense opposition and misinformation campaigns, it is critical to examine which factors are associated with individuals’ vaccination intentions.

In this context, we first focus on altruism as a determinant of COVID-19 vaccination intentions. Altruism is defined as the degree to which an individual desires to improve the welfare of others without expecting anything beneficial in return [8]. Vaccination can be considered as an altruistic behavior for some individuals because its recipient bears the burden and cost of taking it, while it provides a social good to others [9]. It offers two positive externalities: a direct externality that reduces the possibility of infecting family members or close associates and a collective externality that reduces the possibility of infecting the general population [10]. Self-focused individuals may not be willing to see the benefits of vaccination beyond what it can do for their own welfare [11]. However, because altruistic individuals care about others, they would recognize the risks that not getting vaccinated pose to their family members, local residents, and fellow citizens [12]. As a result, they would feel accountable for taking action, such as vaccination. Thus, the need for altruism is strong in public health settings, where taking altruistic actions pays immediate dividends by improving the level of herd immunity and protecting those who cannot be vaccinated due to medical conditions.

Altruism began to garner attention during the COVID-19 pandemic when widespread vaccine hesitancy hampered public health efforts to mitigate the severity of the coronavirus [4]. Studies have demonstrated that altruism has positive associations with vaccination intentions [9, 10, 12–14]. For instance, prosocial individuals are more likely to have an increased level of vaccine uptake than pro-self individuals [11]. Individuals’ concerns about others’ welfare are associated positively with vaccination intentions, even if vaccination is voluntary [9]. While not necessarily intending to protect others, individuals may more often pursue vaccination if doing so makes them feel good about themselves [15]. Altruism can also inspire vaccination intentions when vaccine messages delivered to people emphasize the existence of vulnerable individuals, cooperation as a social norm, and people’s past experiences associated with vulnerability [4]. Individuals having altruistic concerns and being sensitive to public shaming—trying to avoid something people say is wrong—are associated positively with willingness to pay for a hypothetical COVID-19 vaccine [16]. Empathy-evoking messages can elevate people’s responses to advocate vaccination [12].

Secondly, we focus on political trust as an additional factor associated with vaccination intentions. Political trust can be defined as a concept that combines three government-related perspectives: performance, process, and integrity [17–20]. Individuals consider their government trustworthy if its performance meets their expectations, if they trust the processes and procedures that produce the performance, and if the government is free from corruption and scandal [17–20]. Political trust is important not only because it is a measure of citizens’ level of trust in the government but also because it is a measure by which citizens may support government policies, including those to which they are not ideologically inclined [17, 21]. Although scholars initially focused on the determining factors of the rapidly declining level of political trust in the 1970s, particularly in the United States, they soon turned their attention to the role played by political trust, paying attention to its outcomes and moderating effects [17, 21–26]. In this study, we focus on the latter: the outcomes and moderating effects of political trust.

Political trust serves as a heuristic for individuals when they evaluate the government [17, 21]. Individuals are often confronted with multiple constraints related to time, information, and resources [17, 21]. These constraints make it difficult to scrutinize the pros and cons of a given government policy [17, 21]. That is where political trust intervenes and provides individuals with a useful evaluative tool concerning the government [17]. A heuristic is a psychological shortcut that equips individuals with a tool to swiftly assess a given matter even though they may not possess a firm understanding of it [27]. Political trust serves this heuristic function for individuals [17, 21]. Individuals may not possess intimate knowledge of a given government policy, but they may support or oppose it depending on their level of political trust [17, 21].

The heuristic function of political trust guides our assumption that individuals’ political trust will be positively associated with vaccination intentions. As individuals’ levels of political trust increase, they will be more likely to support a government policy [17, 21]. Vaccination is a vital public health issue and firmly in the realm of the government because it involves meticulous public health policymaking and implementation. Individuals with a deeper level of mistrust toward the government are less likely to trust vaccines and put themselves in the position of receiving them. Thus, individuals with a higher level of political trust will be more likely to exhibit vaccination intentions because of the heuristic function of political trust. Several studies have found that individuals’ political trust level is positively associated with support for vaccines-related governmental policy decisions [28], vaccination willingness and uptake [29], and trust toward the government’s handling vaccine safety [30]. These findings imply the strong potential for positive connections between political trust and COVID-19 vaccination intentions.

More importantly, this study was keen to identify the moderation effect of political trust on the linkage between altruism and vaccination intentions. Altruism is oriented toward helping others; as such it manifests civic virtue because the latter is defined as the character of being a good citizen, which exhibits caring about other citizens and political institutions in a given community [31]. Scholars have noted that civic virtue maintains a reinforcing relationship with political trust [30, 32, 33]. Civic virtue can foster a positive link between citizens and political institutions by ensuring that citizens are actively involved in political institutions and procedures as well as government services [30, 32, 33]. In doing so, citizens become more trusting of political institutions [30, 32, 33]. Because altruism is expected to increase vaccination intentions due to the manifestation of civic virtue and because political trust takes a similar direction because of its heuristic function, the positive interaction between altruism and political trust can bolster individuals’ intentions to receive vaccination. These mechanisms can explain why political trust can help strengthen the positive linkage between altruism and vaccination intentions.

Based on what has been discussed so far, we intend to examine three specific questions. First, does individuals’ altruism matter in relation to their vaccination intentions? Second, does individuals’ trust in political institutions affect their vaccination intentions? Third and finally, does individuals’ political trust affects the linkage between individuals’ altruism and their vaccination intentions? These questions can be developed as the following hypotheses for empirical testing:

Hypothesis 1. Higher level of altruism is positively associated with vaccination intentions.

Hypothesis 2. Higher level of political trust is positively associated with vaccination intentions.

Hypothesis 3. Political trust moderates the positive linkage between the level of altruism and vaccination intentions such that the linkage is further strengthened as the level of political trust increases.

This study brings several insights to the understanding of altruism, political trust, and their interactions in reshaping individuals’ vaccination intentions. First, this study helps diversify the understanding of vaccination intentions by exploring the impact of individuals’ altruism. In doing so, the study illuminates the fact that a seemingly value-oriented concept, such as altruism, can also be a vital tool for policymakers when trying to enhance citizens’ vaccination rate. Second, this study demonstrates that how individuals perceive their political institutions is also a critical factor in understanding individuals’ vaccination intentions. Individuals’ level of political trust may not be directly related to their vaccination intentions, but, by interacting with individuals’ altruism, it can exert a powerful force on individuals’ vaccination intentions. Thus, this study enriches the understanding of the multiple factors positively associated with vaccination intentions. Improving vaccination rates is an important mission for both public health officials and political actors. Public officials need to recognize that how they perform influences citizens’ trust in them. By examining the dynamic linkage among altruism, political trust, and vaccination intentions and bringing psychological perspectives into it, this study provides policymakers with a sophisticated understanding of diverse ways to facilitate the governmental pursuit of improving public health for citizens [34, 35].

For the empirical analysis in this study, we relied on the 2021 Korean General Social Survey (KGSS) and an ordered logit regression; our empirical model yielded a sample size of 306. In the following, we examine the data set, variables, and relevant method used in our empirical model. Then, we interpret the empirical results. Finally, we summarize the results and discuss the implications of the findings.

2. Methods

To test the research questions mentioned above, we employed the KGSS, which is very similar to the U.S. General Social Survey of the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago [36]. The KGSS is regarded as nationally representative data, using multistage area probability sampling of all Koreans ages 18 years and older [36]. Among a series of KGSSs that have been collected since 2003, we relied on the 2021 survey because it is the one that contains all the items relevant to our study variables [36]. Furthermore, the final sample size (n = 306) is relatively low due to the fact that all the relevant variables had to be included in the model. The data were collected through face-to-face interviews, with a total response rate of 50% [36].

2.1. Measures

2.1.1. Dependent Variable: Vaccination Intentions

Vaccination intentions refer to the expressed intentions or motivations to receive the COVID-19 vaccine if it is available [37]. We measured the dependent variable based on a single question: “Are you going to get a COVID-19 vaccine?” The variable ranged from 1 to 4 (1 = I will never get vaccinated, 2 = I will probably not get vaccinated, 3 = I will probably get vaccinated, and 4 = I will for certain get vaccinated).

2.1.2. Independent Variable: Altruism

To measure altruism, the respondents were asked, “Please look at each description and indicate how much each person is or is not like you.” Then, they were asked to answer one pertinent subquestion: “It’s very important to her/him to help other people and do good for the society at large.” The item ranged from 1 (very positively) to 6 (not similar at all). We reverse-coded the responses for analysis (i.e., 1 = not similar at all and 6 = very positively).

2.1.3. Moderating Variable: Political Trust

To measure political trust, the respondents were asked to reveal their confidence in the following four institutions: executive branches of the national government, the local government, the president’s office (Blue House), and the National Assembly of Korea. Each item ranged from 1 (a great deal confidence) to 6 (hardly any confidence). We reverse-coded the responses for analysis (i.e., 1 = hardly any confidence and 6 = a great deal confidence).

2.1.4. Controls

To improve our model specification, this study accounted for several demographic factors that might be associated with COVID-19 vaccination intentions: gender (1 = female and 0 = male), age (1 = < 30 years, 2 = 30–39 years, 3 = 40–49 years, 4 = 50–59 years, and 5 = ≥ 60 years), education (1 = high school, 2 = bachelor’s degree, and 3 = graduate school), income level (from 1 = very dissatisfied to 5 = very satisfied), parent–child coresidence (1 = yes and 0 = no), and health status (from 1 = poor to 5 = excellent).

2.2. Methodology

Before testing our hypotheses, we first examined descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation statistics among the variables used in the empirical analyses. Next, we used an ordered logistic regression because our dependent variable consisted of ordinal scales, which ranged from 1 to 4. For the ordinal dependent variables, conducting a linear regression analysis may generate biased estimates. Consequently, the ordered logistic regression was employed for the empirical models.

3. Results

Table 1 provides Spearman’s correlations for all the variables. As presented in the table, altruism was positively correlated with vaccination intentions (r = 0.14, p < 0.05). In addition, health status showed positive relationships with vaccination intentions (r = 0.15, p < 0.05).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (9) | (10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| (2) | 0.06 | 1.00 | |||||||

| (3) | −0.06 | 0.05 | 1.00 | ||||||

| (4) | −0.00 | −0.02 | −0.32∗∗∗ | 1.00 | |||||

| (5) | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.08 | 0.31∗∗∗ | 1.00 | ||||

| (6) | 0.14∗∗ | 0.21∗∗∗ | 0.59∗∗∗ | −0.15∗∗∗ | 0.02 | 1.00 | |||

| (7) | 0.15∗∗ | 0.02 | −0.31∗∗∗ | 0.18∗∗∗ | 0.24∗∗∗ | −0.19∗∗∗ | 1.00 | ||

| (8) | −0.02 | −0.00 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.09∗ | 1.00 | |

| (9) | 0.14∗∗ | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.10∗ | 0.05 | −0.01 | 1.00 |

- Note: (1) vaccination intentions; (2) gender; (3) age; (4) education; (5) income level; (6) parent–child coresidence; (7) health status; (8) political trust; (9) altruism.

- ∗p < 0.1.

- ∗∗p < 0.05.

- ∗∗∗p < 0.01.

Table 2 shows the results of ordered logistic regression analyses for COVID-19 vaccination intentions. Models 1 and 2 considered the direct effects of all the variables on COVID-19 vaccination intentions; Model 3 added the interaction term altruism × political trust to examine the moderating effects of political trust on the relationships between altruism and vaccination intentions.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (S.E.) | OR | β (S.E.) | OR | β (S.E.) | OR | |

| Gender | 0.052 | 1.053 | 0.051 | 1.053 | 0.055 | 1.057 |

| 0.235 | 0.236 | 0.237 | ||||

| Age | −0.295∗∗∗ | 0.744 | −0.309∗∗∗ | 0.734 | −0.330∗∗∗ | 0.719 |

| 0.113 | 0.113 | 0.114 | ||||

| Education | −0.250 | 0.779 | −0.309 | 0.734 | −0.324 | 0.723 |

| 0.225 | 0.228 | 0.229 | ||||

| Income level | 0.068 | 1.070 | 0.078 | 1.081 | 0.036 | 1.037 |

| 0.160 | 0.161 | 0.161 | ||||

| Parent–child coresidence | 1.110∗∗∗ | 3.035 | 1.072∗∗∗ | 2.921 | 1.167∗∗∗ | 3.212 |

| 0.291 | 0.291 | 0.296 | ||||

| Health status | 0.343∗∗∗ | 1.410 | 0.323∗∗∗ | 1.382 | 0.369∗∗∗ | 1.446 |

| 0.122 | 0.123 | 0.125 | ||||

| Political trust | −0.354 | 0.702 | −0.359 | 0.698 | −2.396∗∗∗ | 0.091 |

| 0.258 | 0.260 | 0.924 | ||||

| Altruism | 0.223∗ | 1.250 | −0.683∗ | 0.505 | ||

| 0.117 | 0.410 | |||||

| Altruism × political trust | 0.567∗∗ | 1.764 | ||||

| 0.248 | ||||||

| Cut point 1 | −3.359 | −2.775 | −6.064 | |||

| Cut point 2 | −1.716 | −1.128 | −4.390 | |||

| Cut point 3 | 0.036 | 0.642 | −2.598 | |||

| Log likelihood | −309.445 | −307.593 | −305.394 | |||

| Wald χ2 | 26.69∗∗∗ | 30.39∗∗∗ | 36.04∗∗∗ | |||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.041 | 0.047 | 0.055 | |||

- Note: N = 306.

- Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

- ∗p < 0.1.

- ∗∗p < 0.05.

- ∗∗∗p < 0.01.

Regarding the control variables, the results of Model 1 show that age is negatively related to vaccination intentions (β = −0.295, p < 0.01), which is inconsistent with some studies showing a positive relationship between age and vaccine acceptance [38–40]. Several findings have also pointed out that those at age 65 or older showed more willingness to receive vaccination compared to those at age 30 or below [41]; the Centers for Disease Control in the United States reported that, as of May 2021, vaccination rates were higher among older adults at age 65 or above than those at age 18 to 64 (63%) [42]; furthermore, an international study found that age correlated positively with vaccine acceptance across the 19 countries [43]. Thus, a reasonable conjecture can be made that there would be positive association between age and vaccination intentions.

As such, it is conceivable that age may be negatively associated with vaccination willingness [44, 45]. In addition, parent–child coresidence is positively related to vaccination intentions (β = 1.110, p < 0.01). It is reasonable that individuals living with their child(ren) at home might be more willing to receive COVID-19 vaccination because they might fear infecting their children by transmitting the virus [46]. Finally, health status is positively associated with COVID-19 vaccination intentions (β = 0.343, p < 0.01). Healthier individuals are more likely to receive COVID-19 vaccines. Individuals with underlying diseases might fear vaccination due to their anxiety that vaccination might aggravate their underlying diseases [47].

The results support hypothesis 1 by providing evidence that altruism is positively associated with vaccination intentions (β = 0.223, p < 0.10). It is plausible that altruistic individuals are more likely to receive vaccination because they may believe that increasing vaccination rates protects their community from the spread of COVID-19 by promoting herd immunity [10]. Altruistic individuals who regard the community’s well-being in their decisions are more willing to receive vaccination than pro-self individuals who focus solely on their own interests [4, 11].

Most importantly, for Model 3, we added the interaction between altruism and political trust to explore how political trust reshapes the impact of altruism on vaccination intentions. The findings show that political trust significantly moderated the positive associations between altruism and vaccination intentions (β = 0.567, p < 0.05), supporting Hypothesis 3. Trust in government policies is essential for citizens, as they have to deal with the perceived risk of following government’s official recommendations and regulations [48]. In this regard, altruistic individuals with a greater level of political trust are more likely to accept vaccinations than those with a lower level of political trust because they believe that government capacity and policies regarding vaccines can constrain the spread of the COVID-19 virus and protect the public from ongoing and future pandemics [49, 50].

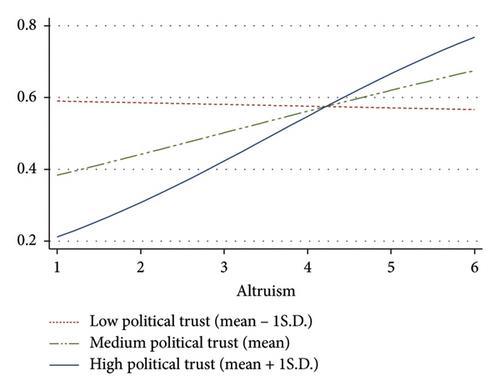

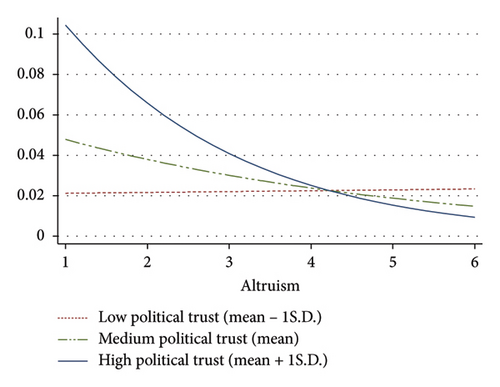

To fully capture the interactions between altruism and vaccination intentions, political trust’s moderating effects are visualized in Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 shows that, compared to individuals with a low level of altruism, individuals with a higher level of altruism are more likely to get vaccinated “for certain” when their level of political trust increases, defined as one standard deviation above the mean (indicated by the solid line) than when their level of political trust decreases, defined as one standard deviation below the mean (indicated by the short-dashed line). In contrast, Figure 2 illustrates the predicted probability of “I will never get vaccinated.” Individuals with a higher level of altruism are less likely to refuse to be vaccinated than those with a lower level of altruism when they exhibit a greater level of political trust.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed that developing vaccines is one thing, but administering them is a different matter [5]. Despite significant health benefits, including shortened hospitalizations and reduced death rates, vaccination has generated vehement opposition from some individuals [51].

Within this context, we explored two issues. First, we examined whether individuals’ altruism as well as individuals’ level of political trust is associated with individuals’ COVID-19 vaccination intentions. Second, we examined whether individuals’ level of political trust functions as a facilitator that helps magnify the positive linkage between individuals’ altruism and their vaccination intentions. The results show that individuals’ altruism was positively associated with vaccination intentions.

Although this study relying on a Korean case did not find a direct relationship between political trust and vaccination intentions, other studies have found that positive relationship between the two variables exists [30, 52, 53]. For instance, a survey study based on French and Italian participants found that political trust is positively associated with individuals’ willingness to conform to governmental restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic [52]. Several studies found that political trust makes a positive impact on how citizens view governmental efforts to ensure vaccine safety and that trust in how government handles vaccine approval and development is positively connected with the likelihood of vaccine take up [30, 53].

Still, individuals’ level of political trust served as a moderator as expected, helping to strengthen the positive relationship between individuals’ altruism and their vaccination intentions. Since several studies already explore the roles that altruism plays in the discussion of vaccination, we focus here on implications with respect to the role that individuals’ political trust plays in the area of both vaccination and public health [4, 9, 10, 12, 34].

Improving citizens’ political trust requires identifying the factors associated with political trust. As mentioned earlier, political trust can be defined by three government-related perspectives: performance, process, and integrity [17–20]. Thus, first, it is critical to raise the level of government performance [17]. Failures in handling a crisis—such as a recession or natural disaster—can create serious doubt about the government among citizens. In early 2020, when COVID-19 ran rampant—shutting down cities, overloading hospitals, and resulting in untold fatalities around the world—the South Korean government was proactive in strengthening contact tracing, establishing drive-through testing sites, regulating and ensuring a proper supply of masks, and helping to minimize the number of confirmed cases and hospitalizations [54]. The public noticed those developments, choosing to elect the ruling party as the predominant majority party in the parliamentary election of April 2020 [54]. By contrast, lack of accountability among public officials in overseeing and regulating the halloween party crowd in Itaewon—where hundreds of thousands of people gathered—contributed to a fatal crowd crush, resulting in over 150 deaths of innocent civilians [55]. After the incident, support for the current Yoon Suk-yeol administration plummeted [55].

However, it should be pointed out that unlike South Korea where the government enjoyed relatively high-level political trust during the COVID-19 pandemic, some countries experienced mixed responses from citizens toward the government, crippling the government’s vaccination efforts [52, 56–58]. For instance, in Slovenia, a latent profile analysis revealed a subgroup within the population that exhibited a low level of trust and satisfaction toward the government [52]. The United States witnessed several states where citizens opposed mask mandates and lockdown directives, exhibiting their distrust in government measures [59]. Several European countries also suffered citizens’ skepticism toward government mandates and measures; in France, thousands of citizens protested the introduction of health passes without which they could not access restaurants and bars; in Germany, frustrated citizens in cities such as Berlin protested extended lockdown restrictions [56–58]. These instances illustrate that those poor governmental measures and performance with respect to COVID-19 led to a decline in public trust in the government.

Second, to raise citizens’ political trust, the government needs to improve its transparency. Political scandals attenuate government’s trustworthiness among citizens [19, 20]. For instance, the fabrication of documents for college admission involving the Minister of Justice and his family severely impaired citizens’ trust in the Moon Jae-in administration [60]. The housing scandal—in which dozens of public officials involved in the Korea Land and Housing Corporation used inside information for real estate speculation—led to a lopsided victory in the special mayoral election for the opposition People Power Party in 2021 [61]. As such, policymakers should note that keeping the government free of scandals and corruption and improving its transparency and integrity can build citizens’ confidence in the government.

Third, increasing the fairness associated with political institutions and procedures can also strengthen political trust among citizens [18]. For instance, a recent Pew Research Center survey revealed that citizens in the United States attribute their political distrust to political institutions that do not reflect contemporary public opinion [62]. In the survey, some respondents noted that extreme political polarization between the two parties (Republican and Democratic Parties), political gerrymandering across states that heavily favors the dominant state party, small states unduly dominating politics in the Senate (in which every state is allotted two senators regardless of its size), and the opaque Electoral College system that discounts minority electorates contribute to undermining their trust in the government [62].

Fourth, citizens need to be actively engaged in politics and political processes. When citizens become active in politics, they have an increased level of ownership and trust in the government [32]. Political participation produces positive feedback to citizens, providing them with a sense of political efficacy [32]. For instance, institutionalized forms of participation such as voter turnout are known to be positively associated with political trust levels, although it should be noted that noninstitutionalized participation, such as protest participation or online political participation, is negatively associated with political trust levels [63–67]. Thus, policymakers need to explore avenues whereby citizens’ political participation can be facilitated.

Fifth, building citizens’ trust in the government needs to go hand in hand with community building. Citizens who rarely participate in their local community affairs find it hard to identify common ground and solidarity with other residents [68]. As a result, they grow skeptical and cynical toward politics, becoming distrustful of the government [68]. Thus, identifying and reinforcing avenues to build civic bonds is crucial. Strengthening civic associations and nurturing active citizenship and civic virtues in schools can help restore citizens’ trust and confidence in political institutions.

Finally, the media need to balance their coverage so that citizens can obtain more accurate information, and the government needs to tailor its public messages to social media, which have become an increasingly important source that citizens rely on [69]. During the pandemic, politicization and sensationalism in the media dampened citizens’ confidence in the government [70]. Additionally, the government needs to ensure that its messages to citizens are available through diverse channels, including not just conventional briefings and newspaper outlets but also social media, on which citizens have, for better or worse, heavily relied. During the COVID-19 pandemic, governmental efforts to boost the vaccination rate were often derailed because social media exacerbated misinformation on vaccines and their side effects [71]. In this age of digital transformation, the government needs to customize public health information to diverse media outlets and populations to ensure that citizens are not overtaken and victimized by misinformation.

The present study has some limitations. First, the study is based on a 1-year cross-sectional survey. As such, its results cannot be generalized and applied to populations in other countries. Second, since this study is not an experimental one or conducted in different time periods, its results should not be interpreted as causal, indicating that the explanatory variables cannot be argued to affirmatively cause the dependent variable. Third, dependent and independent variables were measured in one survey [72]. Thus, we cannot know for certain that the results are completely free from a common method bias. Fourth, we focused on altruism and political trust as the main variables that explain individuals’ vaccination intentions, but it is also possible that a multitude of factors other than individuals’ levels of altruism and political trust may affect individuals’ favorable attitudes toward vaccination, and as such, they should have been accounted for in the empirical model. For instance, individuals’ low level of perceived threat was associated with a greater level of vaccine hesitancy [73, 74]. In addition, those who have a greater level of control or confidence in their own health were more likely to have an increased level of vaccine hesitancy [74]. Others have pointed to positive connections between political conservatism and vaccine hesitancy at least in the United States [75]. Finally, our study did not offer a deeper understanding of subpopulations within a population with respect to how individuals perceive the interplay among altruism, vaccination intentions, and political trust [52, 76]. Employing a methodological tool—such as a latent profile analysis that tries to categorize and profile subpopulations based on a diverse set of personal as well as environmental variables—will help provide a sophisticated understanding of how subgroups of individuals perceive vaccination intentions and add localized perspectives [52, 76]. Thus, further studies involving a wide array of factors are warranted to systematically understand individuals’ attitudes and behaviors toward vaccination, a critical issue for public health.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study was supported by research fund from Chosun University (2022).

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available at https://kgss.skku.edu/kgss/data.do (Korean General Social Survey Repository).