Communication Experiences of Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing Patients During Healthcare Access and Consultation: A Systematic Narrative Review

Abstract

Deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals face significant communication barriers in accessing healthcare services, leading to misunderstandings, misdiagnoses and experiences of marginalisation and discrimination. This study aims to explore these challenges and identify areas for improvement. A systematic narrative review was conducted, involving a comprehensive search and thematic synthesis of data from six electronic databases, including studies up to November 2023. Twenty-two studies were identified (15 qualitative, four quantitative and three mixed methods). Two main themes were generated: challenges related to the role of the interpreter and the need to shift cultural competence. These themes are composed of six subcategories: preferred style of communication, lack of access and continuity of care, trust, disconnected language, disempowerment and misinformation leading to health consequences. The study highlights the importance of considering the unique needs of deaf and hard-of-hearing patients in healthcare environments and promoting cultural competence and effective communication to improve healthcare accessibility and outcomes.

1. Introduction

It is estimated that 11 million people are deaf or hard-of-hearing, and 151,000 people are British Sign Language (BSL) users, in the United Kingdom [1]. Deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals encounter distinct challenges when seeking healthcare and consultation services [2–4]. Several factors relating to the built and nonbuilt environment can impact equitable and effective healthcare experiences for deaf and hard-of-hearing patients. Nonbuilt environmental factors may include effective communication, and cultural competence among healthcare providers. Communication barriers between healthcare providers and deaf patients can lead to misunderstandings and misdiagnoses and ultimately impact the overall healthcare experiences, including experiences of marginalisation and discrimination in healthcare settings [5]. In addition, the lack of awareness and accommodations within healthcare settings may further contribute to disparities in access and quality of care for this population [6, 7]. Physical factors relating to the built environment, such as spatial, visual, and audio-related qualities of waiting rooms and other clinical settings, impact upon accessibility. Undeniably, there are several complex factors at play for deaf or hard-of-hearing individuals accessing health care.

- 1.

Ask: Staff must ask patients if they have communication needs and what support they require, including their preferred method of communication and contact.

- 2.

Record: These communication needs must be clearly documented in the patient’s records.

- 3.

Flag: An alert or flag should be used to ensure all staff are aware of the communication needs and know how to arrange appropriate support.

- 4.

Share: This information should be shared with other relevant healthcare and social care services.

- 5.

Meet: NHS services must be prepared to interact with patients using various methods, and if a BSL interpreter is needed, one should be booked for every appointment.

The AIS is only considered as being fully implemented when all five steps are completed, and the patient’s communication needs are met [8]. While this standard is a legal requirement, the Deaf Health charity, SignHealth, recently released a review of the NHS AIS, which signifies this is not happening [8]. Despite this policy, SignHealth’s review shows that in 2022 only 11% of patients covered by the AIS had equitable NHS access and 67% of deaf people reported that they had no accessible method of contacting their GP. This report has highlighted concerns with NHS accessibility including phone, online, and face-to-face appointments, 999 emergency services calls, and follow-up treatment communications. The organisation has also recognised challenges within NHS consultations such as the lack of an interpreter or available tools used by deaf individuals, such as Type Talk/Text Talk, and lack of services for non-English-speaking deaf individuals. This has a huge personal impact, including embarrassment, misinformation, exclusion, and isolation [4].

Ensuring equal access and quality care for all individuals is an ongoing challenge across healthcare and consultation services. Deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals are among the often-overlooked groups, whose unique needs and experiences within the healthcare system warrant careful examination. Considering intersecting social identities such as race, gender, and class within the deaf community is also crucial, as this may uniquely impact the overall experience.

An evidence-based review of healthcare access and consultation experiences for deaf individuals is essential for driving equity-driven change and improving NHS services. Using a systematic narrative review strategy, this review seeks to examine existing evidence into communication experiences of deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals while accessing healthcare services, and during consultations. The goal is to pinpoint key areas for communication improvement and propose recommendations that can foster a more inclusive and accessible healthcare environment for the deaf community.

2. Methods

This study followed a systematic narrative review design in which a systematic search strategy was completed alongside a thematic synthesis of the retrieved data. As this is an under-researched area, utilising this design, as opposed to a traditional systematic review, supported the inclusion of both quantitative and qualitative evidence [9, 10]. This methodology facilitated more flexible inclusion criteria, enabling a broader range of studies to be considered while ensuring a transparent and rigorous process for literature selection and analysis. This review did not require ethical approval as it involved a secondary analysis of publicly available documents.

2.1. Search Strategy

A study protocol was developed by GWM, and all remaining authors contributed to this. This protocol was developed using the PICO framework using search terms based on the following: patient/population, intervention, control and outcome (Table 1).

| Population: | Deaf∗; hard of hearing; hearing − impairment∗ |

| Intervention: | Healthcare; NHS, ‘National Health Service’; GP, ‘general practice’; ‘primary care’; ‘secondary care’ |

| Comparison/control: | N/a |

| Outcome: | Experience∗; outcome; satisfaction; exclusion; access; consultation |

The following databases were systematically searched due to their relevance to the research aim: ASSIA; CINAHL ultimate; Emerald Journals; Health Research Premium Collection; PsycArticles; Web of Science. The search was limited to the abstract only for each database and included papers published until November 2023. The search strategy presented in Table 1, including wildcard and truncation methods, was modified to fit each database’s requirements. The systematic search strategy utilised a comprehensive set of inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2).

| Inclusion Criteria: | • Only participants from the deaf community included |

|---|---|

| • Only papers which focus on communication within healthcare access and/or consultation to be included | |

| • Papers presenting primary evidence using any methodology included | |

| • International studies included | |

| • Only papers published in English included | |

| • Only studies involving participants aged 18+ included | |

| • Papers from patient/person living with deafness perspective only | |

| • Peer-reviewed papers only | |

| Exclusion criteria: | • Review papers, commentaries, opinion pieces, and grey literature, such as preprints and conference abstracts excluded |

| • Papers not solely focussed on hearing impairment (e.g., papers discussing wider disability) excluded | |

| • Papers from only interpreter/healthcare professional/family member perspective excluded | |

| • Simulation studies excluded |

2.2. Selection Process

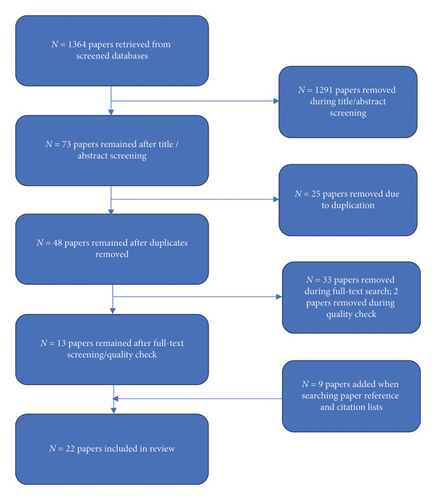

A total of 1364 papers were retrieved across all databases between 23 November 2023 and 29 November 2023. The summary of papers identified from each database were as follows: ASSIA = 364, CINAHL = 388, Emerald Journals = 0, Health Research Premium Collection = 284, PsycArticles = 8, Web of Science = 320. From these, 73 papers were downloaded following an initial title/abstract search. After removing duplicates, 48 remained. All 48 studies were divided across the research team, and an independent full-text search was carried out on each. A team discussion was held to consider which papers should be included in this search and which should be excluded. Discrepancies were resolved through group discussion until a consensus was reached among the reviewers. After these full-text searches were carried out, 33 further papers were removed. Reasons for exclusion of full-text studies were due to the following: study not focussing on communication (n = 12), participants being only healthcare professionals or interpreters (n = 7), paper being a review (n = 6), the paper not being peer-reviewed (n = 3), paper not being primary data (n = 3), the paper being unavailable (n = 1), and the paper being an intervention study (n = 1). In some cases, papers passed the abstract search and were later removed at full-text stage, despite not meeting inclusion criteria; however, this was done when the abstract was unclear/further clarification was needed in-text. Once papers were sifted for their content, a quality check was carried out using the appropriate Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool (https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/). Two further papers were removed due to poor quality. At this stage, 13 papers remained.

Reference and citation searches were carried out for each of the remaining papers, which led to nine additional studies being included in this review. Upon completion of the sifting process, 22 papers were included in this review. The search results are reported in full in the final systematic review and presented in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Figure 1).

2.3. Data Extraction

Only data relevant to the aim of this systematic review were extracted. We extracted the following data from the included papers: author(s), title, year published, aim, research design and methods, participants, data collection methods, country, key findings related to the experiences of healthcare access and consultation. The generated themes/subthemes identified by the paper authors were reviewed and included when appropriate.

2.4. Data Analysis

Each included paper was analysed using the three-stage thematic synthesis method proposed by Thomas and Harden [11] (Table 3).

| Thomas and Harden’s [11] process | The process carried out within this study |

|---|---|

| (1) Line-by-line coding | This stage involved a detailed examination of text, where each line was coded for specific concepts and ideas. G. Wilson-Menzfeld and C. Jackson-Corbett carried out line-by-line coding for all included papers |

| (2) Development of ‘descriptive themes’ | G. Wilson-Menzfeld and C. Jackson-Corbett synthesised data within each paper to develop clear descriptive themes that reflect the core findings of the literature |

| (3) Generation of ‘analytical themes’ | This stage involved moving beyond the descriptive themes, engaging in deeper analysis, and relating themes to each other and to the overall review question. Team discussions were conducted to evaluate coding quality and to analyse the initial descriptive themes critically. After these discussions, G. Wilson-Menzfeld, J. R. Gates and G. Erfani collaboratively developed analytical themes and subthemes |

3. Results

Of the 22 papers included in this study (Table 4), 15 were qualitative papers, four were quantitative, and three were mixed methods. Papers were conducted across the globe: Brazil (n = 1), Germany (n = 1), Greece (n = 1), Italy (n = 1), Norway (n = 1), South Africa (n = 2), the United Kingdom (n = 2), and the United States (n = 13). Two themes were generated from this review: The role of the interpreter and the need to shift cultural competence. Each theme has its own subthemes (Table 5). A breakdown of which papers contributed to each theme and subtheme is provided in Table 6.

| Year | Author(s) | Aim | Design | Participants | Data collection | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Steinberg et al. | To investigate the knowledge, attitudes, and healthcare experiences of deaf women | Qualitative | Deaf women (N = 45) | Focus groups, semistructured interviews | The United States |

| 2004 | Iezzoni et al. | To understand perceptions of healthcare experiences and suggestions for improving care among deaf or hard-of-hearing individuals | Mixed | Deaf/Hard-of-hearing individuals (N = 26) | Semistructured group interviews | The United States |

| 2006 | Steinberg et al. | To better understand the healthcare experiences of deaf people who communicate in American Sign Language | Qualitative | Deaf individuals who communicate primarily in American Sign Language (N = 91) | Focus groups | The United States |

| 2009 | Reeves & Kokoruwe | To assess deaf peoples’ access to primary care within the north-west (NW) region of England | Mixed | Deaf individuals (N = 98) | Interviews | The United Kingdom |

| 2013 | Cabral et al. | To develop a richer understanding of the experiences of deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals in the mental health system and their understanding of and access to recovery-oriented and peer support services | Qualitative | Deaf/Hard-of-hearing patients utilising mental health services (N = 12) | Focus groups/interviews | The United States |

| 2013 | Haricharan et al. | To explore the right to health for signing deaf patients attending health services who cannot communicate in a language they understand. | Case study | 28-year-old deaf woman (N = 1) | Interview | South Africa |

| 2013 | Sheppard | To describe deaf peoples’ healthcare experiences, healthcare access barriers, and communication barriers | Qualitative | Deaf individuals (N = 9) | Multiple interviews | The United States |

| 2014 | Kritzinger et al. | To investigate if there are any additional obstacles, apart from communication barriers, that hinder deaf patients from accessing healthcare facilities | Qualitative | Deaf/hard-of-hearing individuals (N = 16) | Semistructured interviews | South Africa |

| 2017 | Sirch et al. | To explore the communication issues with health professionals affecting healthcare outcomes experienced by deaf people during their hospitalisation | Qualitative | Deaf individuals (N = 9) | Focus groups | Italy |

| 2018 | Funk et al. | To assess the hospital experience of older adults with hearing impairment to formulate suggestions for improving nursing care | Qualitative | Older participants with hearing impairment (N = 8) | Open-ended interviews | The United States |

| 2019 | Santos & Portes | To analyse the perceptions of deaf individuals about the communication process with health professionals | Quantitative | Deaf individuals (N = 121) | Survey | Brazil |

| 2019 | Tsimpida et al. | To investigate the perceived barriers to access to health care among the population with hearing loss in Greece | Quantitative | Deaf/hard-of-hearing adults (N = 140) | Survey | Greece |

| 2020 | Nicodemus et al. | To explore deaf patients’ perception of interpreter presence, its impact on their disclosure of medical information to physicians, and whether this perception affects their assessment of physicians’ patient-centred communication (PCC (PCC) behaviours | Quantitative | Deaf/hard-of-hearing individuals (N = 811) | Online survey | The United States |

| 2022 | Hulme et al. | To explore the lived experiences of culturally deaf British Sign Language (BSL) users who access adult hearing aid services | Qualitative | Deaf individuals wearing one or more hearing aids and who regularly attended adult hearing aid services (N = 8) | Semistructured interviews | The United Kingdom |

| 2022 | James et al. | To study the experiences of adult deaf patient communication with healthcare providers in the emergency department (ED) | Qualitative | Deaf individuals who had used Emergency Department services in past 2 years (N = 11) | Semistructured interviews | The United States |

| 2022 | Mittet and Debesay | To explore how deaf people perceive encounters with the health services in Norway | Qualitative | Individuals using sign language in their daily lives (N = 10) | Semi-structured interview | Norway |

| 2022 | Mussallem et al. | To describe the deaf participants’ experiences with telehealth visits | Quantitative | Deaf individuals (N = 99) | Online survey | The United States |

| 2023 | Hall and Ballard | To assess communication preferences in postpandemic from the perspectives of deaf patients and those who provide interpretation services in healthcare settings | Qualitative | Deaf participants (N = 27) and sign language interpreters (N = 5) | Focus groups | The United States |

| 2023 | Helm et al. | To explore the pregnancy and birth experiences of Black deaf/hard-of-hearing women to identify factors that influence their pregnancy outcomes | Qualitative | Deaf/hard of hearing women who identified as Black (N = 8) | Semistructured interviews | The United States |

| 2023 | James et al. | To describe the perspective of deaf and hard-of-hearing patients on using emergency health services | Qualitative | Deaf/hard-of-hearing (DHH) patients who were 18 years old or older (N = 10) | Semistructured interviews | The United States |

| 2023 | Panko et al. | To explore the pregnancy birth outcomes of women who are deaf to better understand barriers to and facilitators of optimal pregnancy-related health care | Qualitative | Deaf women (N = 45) | Semistructured interviews | The United States |

| 2023 | Rannefeld et al. | To provide insights into deaf and hard-of-hearing (DHH) patient’s perception of medical | Mixed | Deaf/hard of hearing participants (N = 383) | Online survey | Germany |

| Theme | Subtheme |

|---|---|

| The role of the interpreter | • Preferred style of communication |

| • Lack of access and continuity of care | |

| • Trust | |

| The need to shift cultural competence | • Disconnected language |

| • Disempowerment | |

| • Misinformation leading to health consequences | |

| The role of the interpreter | The need to shift cultural competence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred style of communication | Lack of access and continuity of care | Trust | Disconnected language | Disempowerment | Misinformation leading to health consequences | |

| Cabral et al. [12] | x | x | x | x | ||

| Funk et al. [13] | x | x | x | x | ||

| Hall and Ballard [14] | x | x | x | x | ||

| Haricharan et al. [15] | x | x | ||||

| Helm et al. [16] | x | x | x | |||

| Hulme et al. [17] | x | x | x | |||

| Iezzoni et al. [18] | x | x | x | x | x | |

| James et al. [19] | x | x | x | x | x | |

| James et al. [7] | x | x | x | x | ||

| Kritzinger et al. [20] | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Mittet and Debesay [21] | x | x | x | x | ||

| Mussallem et al. [22] | x | x | ||||

| Nicodemus et al. [23] | x | |||||

| Panko et al. [24] | x | x | x | x | ||

| Rannefeld et al. [25] | x | x | ||||

| Reeves and Kokoruwe [26] | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Santos and Portes [27] | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Sheppard [28] | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Sirch et al. [29] | x | x | ||||

| Steinberg et al. [30] | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Steinberg et al. [4] | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Tsimpida et al. [31] | x | x | ||||

3.1. The Role of the Interpreter

3.1.1. Preferred Style of Communication

There were many positive experiences when individuals were provided with an in-house interpreter. Participants felt much more confident and secure when communicating with a healthcare provider when a translator was present [19, 21] and felt that they had better treatment outcomes as a result of improved communication [30]. Within the study carried out by Steinberg et al. [30], almost all participants reported feelings of improved communication, decision-making, and overall experience when using an interpreter. This was particularly the case when medically trained interpreters provided the most beneficial support [4]. Not only did the inclusion of an interpreter facilitate communication but some studies also reported wider benefits, such as being an advocate about deaf culture to medical staff [17], patient reassurance [24], improved decision making within consultation [19] and increased health provider engagement [19].

Other forms of communication were experienced within healthcare consultations, such as virtual interpretation services [19], friends and family acting as interpreters [16], lip reading or reliance on written forms of communication [14, 18]. However, most individuals preferred the on-site presence of an impartial interpreter [4, 12, 21, 24, 26].

Video remote interpreters were often used when on-site when interpreters were unavailable [14, 19, 24]. However, this was problematic, often due to a slow internet connection which led to freezing [19, 24], environmental barriers such as poor sound [14] and device setup [14].

Many individuals also had to rely upon friends or family members to act as interpreters [4, 13, 14, 20, 30]. Many preferred impartial interpreters, provided by the healthcare organisation for several reasons. For some, friends and family were there in a supportive role within the consultation, but it was felt that they were ‘taken advantage of’ [19, p. 52] and there was an expectation that they would provide interpretation [14, 19]. Both studies by Hall and Ballard [14] and James et al. [19] stated that some participants felt that children were inappropriately asked to interpret sensitive medical information which was inappropriate. Furthermore, friends and family are rarely trained in medical sign language or have poor health literacy themselves [14, 19]. This can result in insufficient or incorrect information being passed to patients or healthcare providers [20, 30]. Despite the difficulties often experienced with friends or family members acting as interpreters, some experiences were positive, and participants explained that friends and family were able to advocate for them, as well as provide emotional support when this was otherwise unavailable [16, 27].

Individuals also experienced the use of lip reading (speech reading) and written forms of communication as a replacement for on-site interpretation. Miscommunication was experienced through both of these methods, and the support was often considered as being insufficient [4, 15, 26, 28]. For example, James et al. [7, 19] reported a preference for using nonmedical terminology when communicating with deaf and hard-of-hearing patients, especially when written down. This was due to English not always being their first language [14] and/or lower levels of health literacy within the deaf community [12]. In the qualitative study conducted by Hall and Ballard [14], participants described poor handwriting, difficulties with English and medical terminology, incomplete information provided, and discomfort in writing leading to miscommunication when written language was relied upon. Participants in this study reported feeling as though the back and forth led to the medical professional feeling frustrated and receiving summarised, rather than detailed, information [14].

3.1.2. Lack of Access and Continuity of Care

The systems in place within healthcare organisations are what make translator services accessible or not, and all studies reported an inconsistency between communication support received and individual preferences, particularly in receiving alternative support outlined in the theme above. For many, interpreters were unavailable during medical appointments and hospital stays [12, 17, 21, 26–28] and this included hospital stays when giving birth [16]. Several studies evidenced the need for patients to book an interpreter themselves [7, 12, 19, 26, 30]. However, even the process of booking an interpreter was not straightforward [7, 17, 19, 22, 30] and in some cases led to feelings of distress [19]. In the study carried out by James et al. [19], participants waited up to 8 h in some cases for an interpreter to be available but most often, requests were declined, and interpreter services were completely unavailable. Individuals did not feel confident in broaching this with medical providers, and this led to delays in appointment scheduling [30]. One positive experience was outlined in the study carried out by Panko et al. [24] who described that the healthcare professional’s familiarity with one patient meant that an interpreter was scheduled for every visit ahead of time [24].

As well as the difficulties in accessing interpreters, there was inconsistency in who supported the patient on each visit. This inconsistent access to the same on-site interpreter led to poor continuity of care [16, 19, 24] and the inability to build rapport between the patient and interpreter [19]. This inconsistency of care often resulted in missing information and conflicting information being given to the patient [16]. Contrastingly, continuity of in-person interpretation, as opposed to virtual interpretation services, allowed for further familiarity and rapport building, and as described above, was the preferred method of communication as this allowed some patients to establish trust [19].

3.1.3. Trust

The issue of trust was multifaceted. For some, trust in their healthcare provider was heightened when using an interpreter as individuals were more confident with the health information received during their consultation [19, 23]. However, for others, adding a third person, whether this was an on-site or virtual, provided interpreter, a friend or a family member, into sensitive medical appointments led to feelings of mistrust and violation of privacy [4, 14, 18, 26, 27, 30] or concerns that the interpreter might misinterpret information [12, 28]. There was also concern that medical information would be shared intentionally, or unintentionally, with the wider deaf community [19] and a fear of judgement from the interpreter [19]. In a survey completed by 811 deaf patients, 73% of participants felt that the presence of an interpreter did not impact the medical information disclosed to their healthcare professionals [23]. Of those who did disclose less during medical consultations in the presence of an interpreter, this was partly impacted by the interpreter’s signing ability [23]. Individuals also felt that family, particularly parents, were overprotective of them during these consultations and spoke on behalf of their deaf (adult) child [20]. This led to mistrust that information was not passed on appropriately [20].

3.2. Cultural Competence

3.2.1. Disconnected Language

There was often a disconnection between the deaf patient and healthcare provider through the language they used, including body language and consultation style. Many studies reported patients feeling as though healthcare professionals did not consider the impact of their own language and power differentiation on the consultation, particularly in the absence of an interpreter [19]. Individuals felt that, at times, communication with healthcare professionals was hindered as they spoke too quickly [18], wore a mask to cover their face [18, 28], spoke too loudly [13], were impatient [28], or their accent impacted understanding [13, 18]. In a study by Reeves and Kokoruwe [26], participants noted that successful communication was achieved with a nonsigning healthcare professional when they took the time to understand the patient’s individual communication needs [26]. Participants within reviewed studies recommended that healthcare professionals should repeat information [7, 13], make sure that the patient understands the information given to them, particularly when using medical terminology which can hinder understanding [18, 21, 28], remove face masks [7], use facial expressions to support communication [30, 28], provide in-depth information [24], be patient and not rush the consultation [4, 13, 24], use visual aids, notes or gestures [4, 13, 27], answer all questions [24] and articulate words clearly [30].

Many studies evidenced the way in which healthcare professionals conducted appointments when an interpreter was present, often speaking directly to the interpreter, or other person in the room, as opposed to the patient themselves [18, 20, 29]. This led to feelings of exclusion and being treated like a child or someone with cognitive impairment [20, 29]. Reeves and Kokoruwe [26] reported that deaf patients were more likely to feel as though their GP did not listen to them, did not treat them with courtesy or respect and felt that they were wasting their time compared to a national comparative sample [26]. Participants felt a lack of compassion and sensitivity from healthcare professionals [18] and felt as though the health professional kept the consultation shorter than they would for hearing patients [18, 20, 26]. It was recommended that the healthcare professional should face the patient throughout the consultation [7, 21].

The lack of shared language and consultation style between patient and medical professional led to negative feelings of patient’s own health ‘knowledge, behaviours and attitudes’ [30, p. 735]. This lack of shared language also led to feelings of frustration, mistrust and fear caused by a desire to communicate vs. the actual ability to communicate [4, 13, 18, 29]. In some cases, it also led to avoidance of sharing communication barriers with health professionals [13]. There were barriers which meant some individuals felt uncomfortable asking healthcare professionals to repeat themselves or to explain further [20, 30]. It was also often perceived that healthcare workers did not have time to put these measures into place within their own communication, primarily through lack of time but this increased feelings of discrimination and unease [19, 29]. It led to mistrust and disrespect through a lack of understanding of their needs [7, 14, 18, 19, 26, 29].

3.2.2. Disempowerment

Many patients discussed feelings of disempowerment and a lack of autonomy in relation to their health. Through a lack of understanding of deafness, or deaf culture, appropriate information may not be offered, or alternatively, involvement in decision-making may not happen [18, 29, 30]. This was often caused through a lack of understanding from staff within healthcare organisations or staff not being able to communicate effectively through sign language [17, 29]. While most feelings of disempowerment arose when interpreters were not present, participants in the study conducted by Hall and Ballard [14] discussed feeling a lack of autonomy, specifically when friends and family were interpreting for them, as they often left them out of communication and out of decision-making.

Through disjointed cultural understanding of deafness, individuals often adapted their own behaviour. However, this behaviour could be seen as hostile and threaten the relationship between the patient and healthcare professional [29]. Some studies reported that people did not want to clarify their understanding to/from medical professionals [13] through ‘shyness, lack of confidence, or appearing ignorant’ [20, p. 382], feeling ‘stupid’ when attempting to speak English [18, p. 358], withdrawing [18, 25] or not knowing what to ask [30]. Participants often assumed that their healthcare provider would tell them everything they needed to know without asking additional questions, and therefore did not seek further information voluntarily [30].

The virtual environment in which an individual needs to access healthcare systems was also disempowering. For example, booking appointments could be problematic [4, 13, 17, 18, 28, 31], particularly via telephone [13, 17, 18] and through automated systems [18]. Some relied on family members or friends to make these calls [17]. In one positive example, an email address was provided which afforded the patient ‘independence and equality’ [17, p. 748]. One paper specifically focussed on telehealth consultations [22]. Of the 99 participants who completed the survey, 66% experienced challenges with communication during these appointments. Almost all participants preferred to see their healthcare professional on the screen (97%) to aid lip reading and body language interpretation; however, poor video quality, chat/email issues, difficulty obtaining health information and advice and difficulty with interpreters negatively impacted the quality of these consultations [22].

Participants also discussed the huge role of the environment in feelings of inequity, particularly inequities faced within waiting rooms [13, 17, 18, 20]. Participants within the qualitative study conducted by Hulme et al. [17] highlighted the inappropriate layout of the waiting area which led to patients mistrusting the speaker system [13, 17]. Individuals worried that they would miss their appointment through this system [17, 18] or not know the correct queue to stand in [20].

Over time, this lack of cultural competence within the built, and nonbuilt, environment led to patients withdrawing from the healthcare system [25, 28], a lack of understanding of the patient’s own medical history [20] and fear and helplessness within these processes [25, 29]. Participants in one study reported feeling ‘helpless and dependent on the hearing’ [25, p. 4]. However, deaf patients have the right to be active participants in their own health decision-making, allowing them to manage their own health [29].

However, individuals whose medical practitioner had some knowledge of deafness/deaf culture were preferred [4, 14, 21, 26, 29] with patients willing to travel further to connect with these practitioners [30]. Participants in the study conducted by Sirch et al. [29] did not expect healthcare professionals to understand sign language, and they did expect them to be informed about deafness and the deaf culture. Due to this lack of cultural understanding, patient characteristics can be misunderstood, such as their speech, tone and attitude [29].

3.2.3. Misinformation Leading to Unintended Health Consequences

Miscommunication between the healthcare professional to patient often led to unintended health consequences. This miscommunication was commonly experienced through lack of support provided, nonmedically trained interpreters being available, or only partial information being passed on [4, 12, 15, 16, 24]. These unintended consequences were far-reaching and included medical and surgical procedures being carried out without understanding or consent [24, 28, 30], lack of understanding of aftercare following hospital discharge [7, 19, 26], lack of understanding about their situation, illness or medication received [16, 18, 26, 28, 30] and poor adherence to medical treatment and medication [7, 15, 20, 26, 27, 31]. Individuals did not feel empowered to seek understanding on these issues and this inadequate information received led to confusion when symptoms remanifested [7] and feelings of fear [4], and caused distress and discomfort [30] and embarrassment and anxiety [13, 18, 30]. In most extreme cases, lack of understanding through poor communication led to termination of pregnancy [30] and loss of a baby [16]. Furthermore, in a case study presented by Haricharan et al. [15], the patient described using a friend, who was hard-of-hearing herself, to act as an interpreter in the absence of one. Her friend did not understand the medication prescribed by the medical professional and could not pass on adequate information to the patient. As such, the patient did not use this medication which may have prevented her from becoming HIV-positive [15]. Not being able to effectively communicate with medical professionals led to feelings of isolation, shame and confusion [20]. This could lead to the consequence of nonattendance [25].

4. Discussion

4.1. The Role of Built and Nonbuilt Environment Factors

The findings of this systematic narrative review indicate that the built environment in healthcare settings plays a significant role in the experience of deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals when accessing and using healthcare services. Although less stressed in the literature, features such as signage, lighting and acoustics can impact the ease of navigation and communication for deaf individuals. For example, spatial and visual qualities of waiting rooms and other clinical settings, such as colour contrast and directional arrows, can assist in wayfinding, while lighting can help to ensure that facial expressions and sign language are easily visible [4, 14]. In addition, acoustic design can help reduce background noise and echo, improving speech clarity and making it easier for hard-of-hearing patients to understand what is being said. This issue is more problematic in noisy environments such as hospital settings where older adults with hearing impairment are more likely to feel ‘distressing and exacerbated these feelings of frustration and helplessness’ [13, p. 31]. By considering the needs of deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals in the planning and design of healthcare facilities, healthcare providers can help to improve accessibility and ensure that all patients receive quality care. Much of this can be achieved through the active involvement of deaf sign language users and interpreters in the design, (re-)development and evaluation of clinical settings to ensure the accessibility and inclusivity of healthcare environments and services.

Nonbuilt environment factors such as effective communication access, which includes the availability of qualified sign language interpreters and the use of communication aids like video remote interpreting, are fundamental to quality care [7, 19, 24]. Attitudes and cultural competence among healthcare providers and staff greatly influence patient–provider interactions and the overall patient experience [13, 20, 26]. Positive attitudes, cultural awareness and respectful communication foster trust and improve healthcare outcomes [19, 23]. Additionally, supportive healthcare policies and procedures, such as flexible scheduling and accessibility accommodations, enhance accessibility for deaf/hard-of-hearing patients [8, 12]. Patient empowerment through education on rights and resources, community support networks and advocacy efforts further contribute to a more inclusive healthcare environment. The AIS was introduced to ensure that NHS patients had the legal right to information in a format they would understand, and this includes interpreters and communication aids; however, evidence suggests this does not always happen (HealthWatch, 2022). Ultimately, addressing nonbuilt environment factors such as communication, attitudes, policies and support systems is essential for ensuring equitable and effective healthcare experiences for deaf and hard-of-hearing patients.

4.2. Need to Promote Cultural Competence in Health Care

There is growing recognition of the need to facilitate communications with deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals in healthcare settings by operationalising various aspects of cultural competence, involving further understanding and respecting the cultural and linguistic diversity of this community. It requires healthcare providers to recognise the unique communication needs of deaf and hard-of-hearing patients and to provide effective communication using qualified sign language interpreters, assistive technology and other communication aids. The AIS review conducted by HealthWatch (2022) remarked that the AIS does not go far enough and does not cover the importance of ensuring that services are culturally competent. Analysis revealed that misunderstanding other cultures can lead to difficulties for many minority ethnic communities (HealthWatch, 2022). Cultural competence in health care should also include recognition of deaf culture and deaf awareness. According to the literature reviewed in this study, disconnected language between deaf and healthcare providers [18–20, 29], as well as a sense of disempowerment, can have serious consequences for the health and well-being of deaf patients [13, 14]. In healthcare settings, disconnected language can lead to misinformation, misdiagnosis, incorrect treatment or inadequate health care, which can have negative impacts on the health outcomes of deaf patients [12, 15, 16, 18]. Moreover, disempowerment can result in feelings of frustration, mistrust, exclusion and dissatisfaction with healthcare services, leading to lower utilisation of healthcare services [4, 29]. Disconnected language can occur due to a variety of factors, such as the lack of qualified sign language interpreters, inadequate training of healthcare providers on deaf culture and communication or the use of ineffective communication methods [19, 26]. Addressing disconnected language requires healthcare providers to recognise the unique communication needs of their deaf patients and to provide effective communication through the use of qualified sign language interpreters, assistive technology and other communication aids.

4.3. Wider Disability Literature Around Disempowerment

The lens of disability literature, particularly focussing on disempowerment, offers critical insights into the areas that require improvement to enable the deaf and hard of hearing to have a better experience of accessing and consultation healthcare services. Barriers such as inadequate communication methods, limited health education in accessible formats and cultural insensitivity contribute to disempowerment by hindering individuals’ ability to understand and communicate effectively about their health [18, 20, 29, 31]. Empowering strategies should include implementing sign language interpretation, providing health information in accessible formats for all, including patients with multiple disabilities (e.g., blind and deaf), training healthcare providers in deaf cultural competence, ensuring accessible facilities, fostering patient advocacy and peer support programs and advocating for policy changes that prioritise inclusivity and equity. As the findings of this review indicate, there is a critical need to improve healthcare professionals’ understanding and awareness of the deaf and hard of hearing, their needs and expectations when visiting healthcare services. This is more urgent among those healthcare professionals at the front line of engagement and communications. Ultimately, these initiatives should aim to create an inclusive healthcare environment where deaf and hard-of-hearing patients can navigate systems confidently, access necessary care and actively participate in their healthcare decisions.

4.4. Intersectionality in Studying the Experience of Deaf Patients

The findings of this review reveal that less attention has been devoted to studying the experience of deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals through an intersectionality lens. This approach helps to understand how other social identities, such as race, gender, class and disability, interact and influence the experiences of individuals within healthcare systems. By examining these intersecting identities, we can identify unique and often marginalised experiences that affect access to healthcare, quality of care and health outcomes for deaf individuals. For example, as discussed earlier, research highlights that sign language users who belong to racial minority backgrounds, such as non-English speaking or speakers of English as a foreign language [12, 14, 18] or Black women [16], face compounded barriers in accessing healthcare services. These individuals encounter linguistic and cultural barriers alongside other systemic racism and discrimination. Gender dynamics and economic status within deaf communities can further exacerbate disparities in healthcare access and outcomes. Healthcare providers can promote health equity by recognising and addressing these intersecting axes of identity. They should develop inclusive and effective care approaches for deaf and hard-of-hearing patients.

5. Implications for Policy, Practice and Future Research

The themes and discussion from this literature synthesis have implications for policy, practice and research. The findings align with recommendations from organisations such as SignHealth. Deaf individuals, interpreters and others who engage with the deaf community should be actively involved in designing, planning and evaluating NHS facilities and services. Policymakers should prioritise the inclusive design of new or refurbished NHS properties, with input from the deaf community. This may include improved building layout, signage, lighting and acoustics.

Enhancing cultural competence across all NHS organisations should be prioritised to help foster trust and improve health outcomes in the deaf community. All staff in NHS organisations should be trained regarding attitudes, awareness, patient rights, legal requirements and inclusive communication. This should be bolstered by the rigorous implementation of the AIS and supportive policies within all NHS organisations.

The AIS is a legal requirement aligned with the Equality Act 2010. The AIS helpfully sets out five steps to ensure that healthcare information is accessible. As this is a legal requirement, NHS organisations should fully adopt these steps and utilise the wealth of information provided by SignHealth, The Royal National Institute for Deaf People (RNID) and other charities. Qualified interpreters and communication aids must be available to support effective communication throughout the NHS access and consultation journey for the deaf community. This will ensure accessibility for deaf patients and ensure that NHS organisations comply with the law surrounding the AIS.

While compliance with the AIS is a legal duty, there is no central reporting requirement and organisations do not have to inform NHS England of their compliance. However, Care Quality Commission [32] monitors the AIS during inspections, by talking to staff and people using the service, and through provider information requests. Commissioners must also seek evidence from providers of their compliance, through NHS Standard Contract requirements. Noncompliant organisations explore risk complaints, legal challenges and patient safety implications.

Future research should focus on exploring compliance across NHS organisations, identifying areas for improvement and understanding the consequences of legal challenges due to noncompliance. Additionally, research funding should be dedicated to studying the unintended health outcomes in the deaf community resulting from noncompliance with the AIS.

6. Strengths and Limitations

A key strength of this systematic narrative review is a comprehensive examination of primary studies that reported unmet needs specific to deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals and the importance of addressing these needs when accessing and using healthcare services. Additionally, including different types of studies globally and synthesising their findings of qualitative and quantitative evidence strengthened the review. It is important to note that the number of studies from African and Asian countries accepted for this review is significantly lower than other regions, such as the EU. This may have been a result of the search terms relating to healthcare settings, as some were specific to healthcare practices carried out in the United Kingdom and could have limited the studies retrieved in this review. Therefore, it is necessary to exercise caution when interpreting the findings and drawing conclusions about the experiences and unmet needs of deaf individuals in these regions.

This review is limited in scope as only papers meeting the key criterion of communication experiences within healthcare access and/or consultation were included. The review was also limited to studies from the perspective of deaf or hard-of-hearing patients/persons. These eligibility criteria excluded many other studies that may have provided valuable evidence on healthcare access and use for the deaf community. While it was not within the scope of the review to include wider disability literature, this has been drawn upon in the discussion. Additionally, new primary studies may have been published during this article’s peer-review and publication process. Finally, the team decided not to include Scopus as a database within this review due to the overlap of other searched databases; however, we acknowledge that some relevant papers may have been missed and not included as evidence in this review.

7. Conclusion

While the physical environment of healthcare facilities is important for accessibility, the nonbuilt environment—including communications, awareness, policies and supportive systems/organisations—plays an equally significant role in shaping the healthcare experiences of deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals. The promotion of cultural competence in health care is crucial to recognise the unique communication needs of deaf and hard-of-hearing patients and provide effective communication through the use of qualified sign language interpreters, assistive technology and other communication aids. By addressing these issues, healthcare providers can help to improve accessibility and ensure that all patients receive quality care. It is vital to consider the needs of deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals in the planning and management of healthcare facilities to ensure inclusivity and accessibility of healthcare environments and services. The AIS is a legal requirement, and organisations must prioritise compliance. Ultimately, a patient-centred approach that fosters trust, respect and empowerment can lead to better healthcare outcomes for deaf and hard-of-hearing patients.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation and design: G. Wilson-Menzfeld; conduction of review, including analysis and interpretation: G. Wilson-Menzfeld, C. Jackson-Corbett and G. Erfani; manuscript drafting: G. Wilson-Menzfeld, J. R. Gates, C. Jackson-Corbett and G. Erfani. All authors read and agreed on the content of the final submitted manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

This is a review of publicly available papers. All data are publicly available, and all data are fully cited and referenced in this review.