How Children and Young People Disclose That They Have Been Sexually Abused: Perspectives From Victims and Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse

Abstract

Child sexual abuse is a pervasive social and public health concern with high social and economic costs. Children and young people who experience this form of abuse are in danger of serious, ongoing impacts on their development, functioning and overall life trajectory as a result of the lasting influence of complex trauma. The recent research, drawing from young adult self-reports, has found that more than one in three girls and almost one in five boys have experienced child sexual abuse. These alarming figures are not, however, matched by official data reporting rates of substantiated child sexual abuse cases. It is possible that a sizeable proportion of children who have experienced sexual abuse may not be coming to the attention of authorities and, consequently, may not have their needs being met in a timely way, including their need for safety. A question about the disclosure of child sexual abuse emerges, specifically whether, how and to whom children can tell about what has happened or is happening to them. This paper reports on a study focussing on the disclosure of child sexual abuse, based on in-depth individual interviews with 51 adult victim survivors of child sexual abuse. Findings revealed that most interview participants disclosed a multitude of times before being heard and having their disclosures acted upon. Some were never heard. A thematic inductive analysis is presented and discussed, and recommendations are made for policy and practice reform.

1. Introduction

In Australia, the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (The Royal Commission) defined child sexual abuse as “any act which exposes a child to or involves a child in sexual processes beyond his or her understanding or contrary to accepted community standards” [1, p. 9]. In 2023, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) identified in the 2021–22 Personal Safety Survey that 1.5 million adults over the age of 18 had experienced child sexual abuse before the age of 15 [2]. The recent release of the Australian Child Maltreatment Study (ACMS) found that estimates of child sexual abuse prevalence are alarmingly high in Australia, with more than one in three girls and almost one in five boys experiencing child sexual abuse [3].

The rate of official substantiation of notifications of child sexual abuse by statutory child protection services is also of interest. ‘Substantiation’ indicates that there is evidence confirming that the child has experienced or is at risk of experiencing significant harm due to child sexual abuse [4]. The AIHW reports consistently show that child sexual abuse is the least often type of primary abuse reported or substantiated of the four ‘types’ of child maltreatment in Australia (physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse and neglect). The most recent AIHW data, for example, shows that the number of child sexual abuse matters substantiated for all Australian children between 2022 and 2023 was 4120 children [4].

In contrast, substantiated matters of physical abuse in 2022-23 involved 5874 children, for neglect involved 9323 children and for emotional abuse involved 25,839 children. The reported total of 4120 Australian children experiencing child sexual abuse in 2022–2023 significantly differs from the ABS self-report data and ACMS estimates for the same period, which indicate that more than one in three girls and almost one in five boys in Australia had experienced this form of abuse [3].

Along with child protection substantiation rates, the prosecution rates of child sexual abuse through the criminal justice system in Australia appear to be also low. Recent Australian studies report that only a small proportion of reported child sexual abuse offences resulted in police charges and convictions [5, 6]. This issue is more than just an Australian concern. International research suggests that the incidence of self-reported abuse may be up to 30 times greater than official reports indicate, given the barriers identified and other systemic constraints to safe disclosure by children and young people [7].

Given the apparent discrepancy between the rates of actual child sexual abuse and official involvement by, for example, child protection or criminal justice systems, the issue of whether, how and to whom child sexual abuse victims and survivors disclose what has happened to them becomes a matter of importance. This paper is Australian-focused and draws from a more extensive study reporting on experiences of disclosing or trying to disclose from victims and survivors of child sexual abuse. The wider study also investigated the perspectives held by professionals who respond to disclosure around the enablers and barriers for children and young people who had experienced this form of abuse. The paper privileges the voices of victims and survivors, sharing their insights on what facilitated their disclosure of child sexual abuse and what got in the way of telling. The aim is to explore and analyse what enables children and young people to disclose their experiences of child sexual abuse while also identifying barriers that prevent or discourage such disclosures.

2. Child Sexual Abuse Disclosure: A Brief Overview of the Literature

The relationship between the disclosure of sexual abuse in childhood and the importance of external conditions facilitating disclosure over a life course cannot be understated [8]. Research suggests that disclosure of child sexual abuse is a multifaceted and contextualised phenomenon categorised in various ways, including accidental, direct or indirect, purposeful or prompted [8, 9]. One large-scale study examining more than 1737 case files involving child sexual abuse found that more than half of the cases were detected through accidental disclosure or eyewitness detection [10]. Less than one-third of these were purposeful disclosures initiated by the child victim. A study by Allnock [8] also found that disclosures could occur accidentally during conversations or prompted by television programmes featuring sexual abuse as a theme.

Some studies found that disclosures by children and young people about child sexual abuse were enabled by the presence of an open, trusting relationship that served to mitigate against the offender’s silencing influence [7, 11, 12]. This trusting relationship can be either in person or online, depending on the age of the child or young person. In their review of 24 studies, Gorissen et al. [13] found that making available opportunities for young people to disclose online enabled those who may be reluctant to disclose the abuse in person. Another study by Collings et al. [10] as cited in [7] found that disclosure rates increase with age and are often delayed until adulthood. While Tener and Murphy’s [14, p. 392] review of the literature on adult disclosures of child sexual abuse showed that disclosing in adulthood is generally a “purposeful” and thought-through act in childhood, particularly among younger children, and a range of nonverbal signs (for example, gestures or facial expressions) can be interpreted as their own way of disclosing the abuse [15].

Other research suggests that many victims and survivors can be motivated to tell by other factors such as ‘memorable life events’ or ‘significant life changes’, all of which can act as ‘turning points’ where survivors felt motivated to disclose their childhood experiences of sexual abuse [8, 16]. Other factors that facilitate disclosure include the escalation of the abuse or the perpetrator’s behaviour and relationships with peers that act as a reference point for normal sexual behaviour, therefore enabling an awareness that the behaviour was abusive [8, 17].

Conversely, there are a range of factors that hinder or are barriers to disclosure. Strategies employed by perpetrators of child sexual abuse are known to be effective in silencing children, preventing disclosure [9, 18]. Research indicates the capacity of some perpetrators to meticulously plan and execute their abusive behaviours, suggesting, for some at least, a high level of complex knowledge and decision-making processes [19]. A number of context-specific issues are identified in the literature as barriers to disclosure. The literature identifies several context-specific factors that can make it difficult for individuals to disclose abuse. These include internal challenges, such as feelings of self-blame, shame and a sense of undeserved guilt that survivors may experience. Interpersonal challenges are explored by various studies which show that children and young people may live with fear of the consequences of disclosing, including fears associated with family violence, whilst others may experience isolation and a lack of social support [20]. Systemic factors are more widely acknowledged in the literature, citing structural barriers including sociocultural issues and a lack of child-centred services that have the capacity to listen to and hear from child victims and survivors [16].

In summary, a complex web of internal, interpersonal and systemic challenges may work together to prevent children and young people from disclosing their experiences of child sexual abuse [9, 16]. Whilst research evidence is limited in the area of factors enabling disclosure, what emerges as helpful for children to disclose their abuse are professionals and other adults noticing when they are distressed and creating trusting relationships with them to provide opportunities to disclose [21] or being asked directly or prompted to disclose abuse [17]. The people that children elect to disclose to is an important question, with recent research suggesting that when children and young people are feeling unsafe, they are more likely to tell a friend, than an adult professional in a child-serving organisation [17, 22].

3. A Critical Intersectional Framework to Examine Child Sexual Abuse Disclosure

The overarching critical theoretical paradigm framing this study recognises that the lived and living experience of child sexual abuse disclosure can be mobilised to cocreate improved practice and policy [23]. Critical frameworks offer a method of enquiry that question approaches reinforcing powerlessness, aiming to challenge oppressive power relations and structures [23]. In addition to recognising the diversity of experience across the lifespan of survivors of child sexual abuse, the critical theory enables close examination of the interplay of human experiences with the structures, systems and circumstances within which they are situated.

A critical framework to understand child sexual abuse disclosure is necessary given the complex interplay of individual, familial, contextual and cultural issues, with age and gender predictive of delayed disclosure for younger children and adolescent boys [24]. Within this framework, barriers have been categorised as falling within three broad domains: (i) internal barriers, (ii) interpersonal barriers and (iii) wider social barriers [16, 25]. Internal barriers, including complex emotional experiences of guilt, shame, grief, self-blame and fear, can compound with interpersonal challenges, such as family violence, limited social support, mistrust of adults and fear of potential consequences when disclosing the sexual abuse. Together, these factors can significantly impact the decision to disclose.

In addition, socio-political/cultural barriers such as views and attitudes towards abuse, limited resources and structural responses to abuse are also barriers to disclosure [16]. Racially and culturally minoritised children and young people may opt not to disclose for other reasons. The ongoing legacy of colonisation and in particular of forced removal of children acts as a barrier to Australian First Nations children and young people disclosing child sexual abuse [26, 27]. For Australian First Nations Peoples, a level of mistrust in authorities is understandable given that police and child welfare were directly involved in the forced removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families [28].

There may be a number of unique barriers to disclosure in (nonindigenous) ethnic minority communities, defined as those families with a history of migration and who are a minority group in one or more of the following: race, language, culture or religion [29]. Survivors may be dissuaded from disclosure to protect their family and community from shame, stigma or loss of dignity [30]. For example, in South Africa, researchers found that the desire for families to preserve the dignity of the family and avoid shame in the community may have inhibited children from wanting to disclose sexual abuse, consequently prioritising the reputation of the family over disclosure [30]. Similarly, in East Asian communities, the concern that such a negative incident can ruin the family and the victim’s reputation and damage relationships with other community members can also dissuade disclosure from children and reporting from their families [31]. When living within cultural norms promoting self-scrutiny, children feel responsible for their actions and may blame themselves for the abuse or the impacts of disclosing [31].

4. Methods and Research Design

What is known about what influences or enables children and young people to disclose their experience of child sexual abuse, and what are the barriers to disclosure?

A semistructured interview protocol was developed and implemented online. Interviews lasted for between 45 min and 2 h. All participants were over 18 years in accordance with the Human Research Ethics approval, and they were asked to reflect retrospectively on their experience of sexual abuse as children.

4.1. Recruitment Process

The distribution of the recruitment material to potential child sexual abuse victims and survivors was primarily facilitated through the partner organisations, which include the National Centre for Action Against Child Sexual Abuse, Centre Against Violence (Vic), Act for Kids (Qld), the Gold Coast Centre Against Sexual Violence (Qld), Bravehearts (Australia-wide), and Your Town (Australia-wide). Further recruitment was also aided via the distribution of information on social media (e.g., LinkedIn and Instagram). Interviews with victims and survivors were undertaken with 51 adults over the age of 18 years. Inclusion criteria required that participants were 18 years and above, had self-reported or formally reported lived experience of child sexual abuse in Australia (in order to capture data about Australian systems and policy responses to child sexual abuse disclosure) and were willing to participate in an interview. Interested participants were excluded if they were under 18 years old, did not have lived experience of child sexual abuse in Australia or were assessed as having an unacceptable level of risk of harm or high levels of distress that would be exacerbated by being involved in an interview at this time. Participants were remunerated for their time with an online gift voucher; some decided to donate the gift voucher to our partner organisations supporting victims and survivors of child sexual abuse.

4.2. Ethical Considerations

The ethical aspects of this research were approved by Southern Cross University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 2023/172). The consent processes in place ensured the voluntary participation of victims and survivors. The research team provided information sheets and consent forms via email to prospective participants who expressed interest. When a potential participant returned a completed consent form, the research team followed up with them (or their support person) to confirm eligibility using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Where the potential participant did not meet the age or inclusion criteria, this was sensitively explained to them, and they were thanked for their interest. Where there were concerns about the risk of harm or levels of distress (for example, where a participant became visibly distressed), the potential participant was referred back to the partner organisation and/or provided with information about appropriate support services.

4.3. Care, Consent and Trustworthiness

The research team also encouraged prospective participants to discuss the potential benefits and possible risks of their involvement in the interview. The information made it clear that participants could decline or choose to withdraw at any time. They could also ask for the recording to be paused at any time if they wanted to say something ‘off the record.’ A critical component of the approach to consent is that it is seen as an ongoing process [32]. Participants were asked by members of the research team at the beginning of the interview to reconfirm their consent and were reminded about the voluntary nature of their involvement and their right to withdraw consent at any time. They were also invited to assign themselves a pseudonym for the purpose of reporting the findings. Close and careful observation of the tone, silences and hesitations of participants during the online interview was assessed to make sure that they were comfortable to continue with the interview. Despite our best efforts to include people who were First Nations, culturally and linguistically diverse, living with disability and who were identified as LGBTIQA+, our final sample was rather homogenous. The next phase of this research, which involves a national quantitative online survey, will aim to include more diverse participants and collect detailed information about self-reported incidents versus formally reported ones.

4.4. Coding and Analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed, and participants were asked if they wished to review the transcript of their interview, but only a few took up the offer. The data were coded, reviewed, labelled and categorised. An inductive thematic analysis was undertaken to ensure transparency and enable discussion amongst the research team through a phased approach to analysis [33, 34], beginning with immersion in the data with repeated readings of the transcripts, followed by coding data segments. Over a period of 10 weeks, three researchers, both independently and collaboratively, discussed the emerging codes and themes to ensure that confirmation bias did not affect the analysis of results. Themes were reviewed and refined following rigorous discussion amongst research team members, adding to the trustworthiness of the analytic process. Subsequently, the following experiences and conditions were categorised into related and interconnected themes and subthemes.

5. Findings

Of the 51 participants who were interviewed, the vast majority were women (n = 49) above 30 years of age (see Table 1). Most resided in Queensland (n = 17) and New South Wales (n = 14). Most were working (n = 42), studying (n = 13) or studying and working (n = 11). English was the main language spoken at home (n = 47), and the majority of participants were identified as nonindigenous Australians (n = 47), with some having a variety of ethnic backgrounds (n = 19), as shown in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Participants | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 49 | 94 |

| Male | 2 | 6 |

| Age | ||

| 18–30 years | 11 | 22 |

| 31–44 years | 17 | 33 |

| Above 45 years | 19 | 37 |

| Prefer not to say | 4 | 8 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Australian nonindigenous | 28 | 55 |

| Australian indigenous | 1 | 2 |

| Other ethnic background∗ | 19 | 37 |

| Prefer not to say | 3 | 6 |

| Language | ||

| English | 47 | 92 |

| Other | 4 | 8 |

| Occupation | ||

| Employed | 30 | 59 |

| Studying | 1 | 2 |

| Studying and working | 11 | 22 |

| Parenting | 2 | 4 |

| Prefer not to say | 7 | 13 |

| Location | ||

| QLD | 17 | 33 |

| NSW | 14 | 27 |

| VIC | 12 | 24 |

| SA | 2 | 4 |

| ACT | 2 | 4 |

| WA | 2 | 4 |

| TAS | 1 | 2 |

| Prefer not to say | 1 | 2 |

| TOTAL | 51 | 100 |

- ∗including Vietnamese, Latin American, Black African, English, Filipino, Irish, Swedish, Jewish, Maltese, German, Macedonian/Italian, Lebanese, Maori, Dutch, Indonesian, Caribbean, Asian and Swiss.

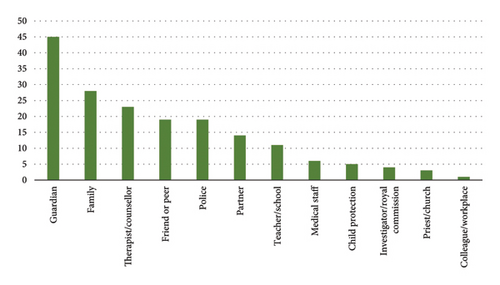

Most participants in this study (n = 47) told us that sexual abuse during childhood happened at the hands of family members or family friends. The highest number of first-time disclosures was when victims were children (n = 23), followed by teenagers (n = 16), and lastly as, adults (n = 9). A small number of participants (n = 3) did not identify when they first disclosed, for various reasons. In terms of who was being disclosed to (either the first, second or third disclosure), it was most often to a parent or guardian (n = 45) or someone within the family group (n = 28) (see Figure 1). For most of the victim-survivors (n = 26), disclosures were made to more than one person at different times and life stages.

In response to the research question: what is known about what influences or enables children and young people to disclose their experience of child sexual abuse, and what are the barriers to disclosure? Findings showed that the majority of survivors had to disclose a multitude of times before being truly heard and having their disclosures acted upon. Disclosures frequently went unseen, unheard or were not acted upon, particularly when first disclosing as a child.

Key themes emerged from a deductive analysis of the data, coding for influencing factors, enabling factors and barriers to disclosing child sexual abuse. Each of these is presented and discussed below.

5.1. What Influences Disclosures of Child Sexual Abuse?

Factors that influenced the decision made by the child or young person to disclose included physical factors such as injury or abdominal pain, developmental factors such as a growing awareness that sexual abuse did not happen to everyone and following an information session where children heard for the first time that sexual abuse was wrong, that they were not to blame and that they should tell someone about it. Some participants described themselves as having a ‘line in the sand moment’ where they decided that enough was enough and they would no longer tolerate the abuse.

5.1.1. Line in the Sand Moment

He wanted to have sex with me and so he took me down to the back of the bush where like no one could hear me. I pretty much thought I was gonna die. I couldn’t walk at the time so I thought, that′s it. He’s gonna kill me. He’s gonna leave me here… He started doing stuff with me and then I just lost the plot and I kicked him… I said you can’t, don’t fucking do this to me… I went off at him. (Marie)

5.1.2. Pain or Injury

I had a sore fanny, so I told my mother because it hurt. I asked my mum why I hurt down there. (Laura).

5.1.3. Realising It Does Not Happen to Everyone

I was around 10 and started like having, you know, sleepovers and stuff. That I realised other families weren’t like this. You know, my friends weren’t moving their wardrobes in front of their doors at night. (Robyn).

5.1.4. Education Sessions

One of my friends hated her stepfather, and my mum said, “Do you think it’s incest?” And I said, “I don’t know what that is”. And she said, “Well…” And I thought, oh, my god, that’s a thing. If it existed enough for people to create a word for it, it meant that I wasn’t the only person in the world that this had happened to… And that provided, I guess, clarity. (Jill).

5.2. Enabling Factors

Factors that enabled children and young people to disclose were, first and foremost, having a person who was safe and trustworthy, who noticed them, heard them and acted to ensure their safety. This person’s immediate responses were central to the child victim survivor having an experience of being believed that was positive and life-changing. Similarly, having access to skilled professionals and support services who understood the dynamics and impact of child sexual abuse was mentioned by many to be critical. Finally, the power of institutions to validate the child’s disclosure by responding appropriately and in a timely way was critical for some.

5.2.1. Being Seen, Heard and Made to Feel Safe

As soon as I said it, he believed what I said… That was a special gift that he gave me that he believed me as soon as I told him… [he] did a very good job of validating and listening to what I was saying. (Ruby)

I feel like she did do the right thing. I think she really did support me. Yeah, I think I just needed to be told, my feelings, they were valid and that I actually had experienced something that could have [affected] me in such a big way. (Holly)

5.2.2. Having a Safe Person to Disclose to

I think I chose the person that could provide me with that sense of personal safety and that I knew would not second guess or question. (Ruby)

My sister… She’s only a couple of years older than me. She just said to me that she would be looking out for me. (Jill)

5.2.3. Access to Professional Support Services

I just went, look, this is me. And blurted it all out. I felt so much lighter walking out of there. I found someone that believed me… and they were gonna support me… [He said] “It′s okay, I′ve got you”. Like just to know that someone believed and was willing to take care of me. (Rosa)

5.2.4. Institutions Acting on Disclosures to Keep Children Safe

I felt very like, nurtured by my teachers. It almost was like they went from being just teachers to being like my protectors. And it was like, okay, don′t worry, we’re going to sort this out. (Rhiannon)

5.3. Barriers to Disclosure

The barriers that the participants faced as children and young people when it came to disclosing their abuse were, at times, overwhelming. Time and again, participants spoke of ways in which perpetrators of abuse created and maintained silence. A number of participants recalled that they were trying to ‘show’ others that something was wrong, for example, via their art or written work at school. According to these victim survivors, this was not noticed or responded to. For many, there was no apparent means of escape when the ‘nonabusive parent’ also acted in ways to maintain silence. This may have been through direct instruction to be silent or by more indirect methods, including showing their own vulnerability or trauma history. Finally, institutions such as police and child protection services were noted for their failure to act and protect.

5.3.1. Perpetrator Strategies to Silence Children

My parents just really liked this person. And so, he was a really big part of our family. He was over at our house multiple times a week, I mean it was it was really like he almost lived there. I mean he’d go home to sleep but he would just come straight back. He used to do this thing where he would act really helpful. So, he would say to my mum, look, you’ve got your hands full with the baby and the toddler. He would say, look you got your hands full, let me take the 2 older ones, and he used to take us out, almost on dates. Like every week, he would have somewhere different to take us. We would go to the shopping centre; we would go for ice cream. (Ally)

There were signs, like, why does this man want you at their house all the time? And why is that man overtly strange? I think my father was groomed by the perpetrators of this particular child pornography ring. (Robyn).

Abusers positioning themselves within the family group meant that they could also leverage and exploit their intimate knowledge of the family to maintain access and to silence disclosures.

5.3.2. Not Being Seen

I think deliberately writing like stories and poetry and stuff like that for teachers… I was like really little, and I’m talking about, you know, suicidal ideation. I’m talking about abuse. I’m talking about, horrible nasty things (Robyn)

5.3.3. No Safe or Trustworthy Person to Go to

Most participants (n = 43) in this study told us that there was a lack of a safe and trustworthy adult to go to or to confide in. A small proportion (n = 8) of the 51 participants said that they did have a safe person to tell. While the data above indicate that most children tried to tell a parent or parent figure, participants also revealed that in attempting to tell, they often learned that this person was not a safe or trustworthy person to confide in.

He had sat down with my parents when I was 11… and said I would like to marry Ally as soon as it′s legally possible… then came and told me that he had had a conversation with my parents and my parents had given permission for me to marry him. (Ally)

I had no protection. My parents already knew that they had a pedophile on their hands and they were absolutely fine with it. They didn’t put any parameters around that or restrictions. They knew that he had sexual feelings towards me. And they gave me absolutely no protection. So, there was absolutely no point for me to talk to them.

I remember my parents saying, as of now, you two could not be alone in the house together… And literally… I remember my parents going to a Christmas party and leaving us alone together and I remember being so scared about the abuse happening again (Rhiannon)

The closer they are to the abuser, whoever your safe person or whoever you think is a safe person, the closer they are to the abuser, the less help you’re ever going to get. Because they can’t deal with it. Sometimes, it’s even extended family, like grandparents, when they find out about it. Because she [my mum] didn’t want my brother to get into trouble. I feel like she was protecting him rather than me. (Meron)

I had tear streaks, and I was pink. And it took her a good 20 min to bother to ask if I was okay. And when I, and she said, oh, are you okay? I said, oh, I just found out I need surgery because of the child sexual abuse I went through, and that′s exactly how I said it. And she put like half a hand on my shoulder and said, ‘I can′t help pay for it’. And I was like, that was not what I asked (Robyn)

Mum looked at me and said everyone’s going to think I’m a bad mum. And I gave her a huge hug and I said it’s not about you being a good or a bad parent (Freya)

Here was this lady in the kitchen, smashing plates like she was just like… Chucking them, she was so upset about what she’d heard, and she was already red-faced. It scared me, and at that point, I was 12; I was still very confused… and I was so scared at that point. I was already trapped in a cycle of abuse. It came to a point where telling was going to be more painful than not telling, and I made a decision not to say anything more at that point even though I had a perfect opportunity to say the details. (Marie)

Feeling a sense of responsibility for their parents’ reactions also caused participants to experience additional layers of guilt, blame and isolation. Laura said, ‘What made it worse was to feel responsible for my adoptive mother falling apart after I disclosed at age 19… She fell apart. She actually got suicidal.’ These responses regarding their children’s safety were significant, as they signalled to the child the inability of the nonabusing adult to respond appropriately to disclosures of abuse. More importantly, participants reflected that there were no discussions about how they would be kept safe, away from future harm or supported.

5.3.4. Silence and Erasure: Being Dismissed, Disbelieved and Discouraged After Disclosure

She made comments like, oh, I experienced something similar to you, but probably much worse and like it would just kind of minimise what I had experienced and so I kept thinking okay then what I’ve had wasn’t very bad. (Holly).

In environments where the abuse was normalised or dismissed, victim survivors were left with a sense of mixed feelings. That is, they knew what they were experiencing ‘wasn’t right’ but the minimisation of child sexual abuse prevented them from understanding the seriousness of what was happening to them. For example, Kim stated that her mother dismissed the abuse as ‘normal stuff’ that ‘teenage boys do’ and that it would be the ‘last time that we’re going to talk about this.’ Another participant, Kylie, reflected that when she told her mother, she laughed, referred to her abuser as ‘a dirty old gentleman’ and then told her “Oh, you’ll be all right”.

I said he’s been abusing me for years, he’s been abusing me since I was 4, and my mum’s response was “exactly”. I was like, okay, so you were fully aware of this. She very much brushed it off and put it in the too-hard basket… and made homophobic jokes, like, oh well, it’s no wonder you’re a carpet muncher. (Robyn)

There was no curiosity from my mother, and with my brother and sister, they actually laughed and told me I was just making up stupid stories. (Laura)

In Lily’s case, she may have had access to people she perceived to be safe adults to disclose to, but her disclosures were repeatedly dismissed, disbelieved or discouraged despite her father having other abuse claims against him. Despite multiple and numerous attempts to disclose her abuse over many years, the recipients repeatedly involved her father, her abuser, instead of acting to ensure that she was safe. These responses reinforced fears that as a child, she would not be heard, that as a survivor, she would not be believed, that disclosing abuse is pointless and that ‘no one will help’.

Every step of the way, I′ve had [my mental health] used against me… saying that I have mental health problems, that I don′t see life the way it is because of my history. I′ve learned the hard way not to tell people. (Freya)

These various acts of silencing, dismissal and minimisation were perceived by victims and survivors during childhood as most often performed by the ‘nonoffending’ parent in isolation; however, at times, they took place in collaboration with the perpetrator of the abuse.

5.3.5. Failure of Institutions to Listen and Act

Silence and secrecy underscored the powerful influence of institutional and familial pressures in preventing disclosure. Participants reflected that institutions, including schools, religious organisations and child-serving agencies, often failed to provide adequate support or to take action when disclosures were made. This included ignoring signs of abuse, failing to report abuse or prioritising the institution’s reputation over the survivor’s well-being. Participants emphasised how systemic issues within institutions, such as schools and churches, affected their experience of disclosure. Participants added that due to these institutional failures, they internalised the message that silence was necessary to protect the family or institutional reputations.

And I told them what [perpetrator] had done. But not a lot of sympathy. They basically were more concerned about the religion. That was sort of like, well, okay, that happened, and it’s not great, but we just don’t talk about it. (Ally)

One participant recalled that she told her local priest, who was close to her family, that her father was abusing her. In response, the priest continued to come to their home for a ‘Sunday roast as if nothing had happened’. Another participant, Kylie, shared how attending a small Catholic school meant that child sexual abuse disclosures were handled by Catholic welfare services, keeping matters within the church and discouraging police involvement. Kylie shared memories of the day she disclosed, but she was forced to maintain contact with her abusers and was advised that ‘a good Christian forgives’, a statement that she remembers as akin to being ‘abused again’. Kylie stated that, as a child, she needed someone to validate her experience, offer support and support her healing. Instead, their silence had ‘nearly as much impact as all the sexual abuse combined’.

They sent me a letter about a month later and said, unfortunately, we have a two or three-witness rule. Unless other people have witnessed you being abused, we don’t believe you… We’re not going to do anything about it. (June)

Additionally, participants recalled being explicitly discouraged from involving law enforcement. Ally, for example, said that she was taught to view the police as enemies, reinforcing the isolation and discouraging external contact and support to protect her family and the institution’s reputation. As Ally shared, ‘We were told the police were basically our enemy; they were Satan.’ Such messaging can keep victims of child sexual abuse trapped in cycles of abuse for years.

Participants emphasised the challenging reality that attempting to disclose abuse is just the beginning. Despite their efforts, many who disclosed were repeatedly met with unhelpful responses by not only family members but also professionals and institutions that should have offered more protection and care. This was a critical finding that survivors often have to disclose their abuse multiple times before being heard, and even then, it does not guarantee a helpful response.

These narratives illustrate the way in which institutional silence can operate on multiple levels within families and institutional settings, creating systematic barriers to the disclosure of child sexual abuse and vulnerability to further abuse.

In the following case study involving Lily, each of the elements identified above in relation to barriers to disclosure is evident.

5.3.6. Lily’s Story

Lily’s earliest memory of her father’s abuse of her was at about four or 5 years of age. Her father was a school principal, and her mother was a teacher.

At the age of 6 years, Lily tried to disclose her father’s abuse to a doctor: “I do remember just complaining to the doctor about this like pain and discomfort down there that I had been feeling… That it really hurt when I went to the toilet”. The doctor dismissed Lily’s symptoms even though she had previously been hospitalised for untreated UTIs. He told her mum that there was nothing to worry about.

At 9 years of age, a child of a family friend alleged Lily’s father of sexual abuse. Lily said she did not really know what had happened but recalled two police officers visiting her house, followed by “some really nice ladies” who she says may have been from child protection. Lily describes a car ride without her mother and that the child protection workers “never actually asked me about anything… We drew a picture of my house… but I didn’t say anything. I didn’t know I was meant to say anything because I wasn’t asked”. Lily recalls after this visit, her mum and dad sat her down and said, “We’re going to have to move”. The abuse continued.

I decided that I would never be able to say anything… because I saw what it did to my family… I saw the way they all spoke about the boy who had accused my dad of those things. So, I was like, they’re gonna speak about me that way.

Lily’s dad was found not guilty. Even though the abuse that he perpetrated continued, Lily did not want to cause any more pain and suffering to her family after witnessing their distress from the trial.

By the time Lily was 15 years old, she had reached a breaking point, “I had stopped eating, lost a lot of weight, and I had started self-harming”, and her friends had noticed. Then, one day, they asked, and “it all came out… They gave me big hugs, and then they went off back to class”. The next day, Lily got a note at school saying her mum was there to pick her up, which she had never done before. “I knew I was in trouble”. Lily got home to find her dad sitting on the couch waiting for her. Her mum said, “You know your father’s really upset. We’ve had a call from the school… You can understand how devastating it is to hear this”. Lily’s heart sank.

Lily’s friends had told about her abuse to a head teacher who was friends with Lily’s father, “she had just called him and said your daughter said this about you”. Lily thought that might have been the end of it, but it turned out that her parents decided to actively silence her disclosure by discrediting her. “My parents spoke to their [my friend’s] parents and said, look, the whole thing’s a mistake, or she kind of made it up.” Lily said when she went back to school, her friends would not look at her, “they wouldn’t talk to me”, and they turned away while everyone in the school was staring at her, “that was probably what hurt the most”.

At 16 years, Lily started seeing a psychologist who was recommended as a trauma expert. “She said that I wasn’t lying. I just convinced myself that it had happened when it hadn’t actually happened”. The psychologist described this phenomenon to Lily “She said, “People are saying that they had been raped when they had not been, but they really did think [and were] convinced that they had actually been raped”. Meanwhile, her father’s abuse continued.

A short while later, Lily was admitted to a psychiatric unit as her condition worsened. Her aunt and cousin raised the alarm once she had been admitted and said they believed her. “They were the first ones who believed me and said they would help me”, she said. When Lily arrived home from the hospital, she found her mum and dad waiting for her again. They made her recant her disclosure. “My mum was over my shoulder, and my dad was kind of walking around listening… and typed out a message to the Aunt saying that it didn’t happen. They made me say because of the medication, I didn’t really know what I was saying and that I have just made it up”, Lily said, adding that her mum supported the lie.

When Lily was 17, she attempted suicide: “I had taken an overdose, and the paramedics asked me what was going on. I obviously was at the very lowest point, so I told them what was happening and said, I can’t take it anymore”. One paramedic returned to the house and spoke with Lily’s dad. When they got in the ambulance with Lily, they said they do not tolerate “bull”. It was clear that they believed what Lily’s dad had said rather than what Lily had said. Then, Lily’s dad got in the ambulance, and they all rode to the hospital. Lily recalls, “I remember just looking up at the ceiling of the ambulance and realising that I was never, ever going to escape this”. There were no questions or follow-ups about the abuse with Lily, neither from the paramedics nor from anyone in the hospital.

About a year later, Lily and her brother followed their dad one night to another house as they suspected that he was harming another child. They looked in the window and caught him “we saw him rape another child”. Lily and her brother called the police, “the police operator asked us if we knew how serious it was, what we were saying. I was trying to say it, but they just wouldn’t hear me, so my brother spoke to them—he yelled it down the phone”. It took 2 hours for the police to arrive. Lily and her brother were waiting on the road in the rain for them. Lily recalls how when they first arrived, the police thought it was nothing, but then “their whole attitude changed pretty quickly”. The police arrested Lily’s dad and took him to the station. He was found guilty on all charges, including Lily’s.

This harrowing case study summarises the key elements of Lily’s story. It certainly highlights the power of the perpetrator’s strategies to silence, the lack of a safe person to go to (including her mother and a range of legally mandated professionals) and the institutional failure to listen and act.

6. Discussion: Not Seen. Not Heard. Not Safe

Most participants in this study argued that when it came to their lived experience of child sexual abuse, responsible adults did not notice that something was wrong, did not listen to or hear them and did not facilitate their safety. This study confirms and extends the prevailing research, particularly those studies that analysed adults’ retrospective experiences of child sexual abuse [8, 14, 35]. The enablers of disclosure are familiar and, not surprisingly, are centred on the presence of a safe and trusting relationship with a responsible adult or friend. These enabling factors are multifaceted and unique to the context of the victim-survivor. Disclosures may be seen as unintended, purposeful, prompted or accidental. Disclosure was not described by most participants as a one-off event but rather a multifaceted iterative process that took place over time, sometimes over decades, with apparent ‘accommodation’ of ongoing abuse between disclosures reported by some [7, 9].

The barriers to disclosure identified by participants in this study far outweighed the facilitating or enabling factors. The perpetrator, as the person responsible for the abuse, was described as employing a range of strategies to ensure that children did not disclose. This, too, is familiar within research examining sex offender behaviours where coercion, threats and other abuses of power were used to silence individual victim survivors, mothers and other family members and the wider social network [16, 18, 36]. In the case of Lily, for example, her father was both a perpetrator and a highly regarded local school principal who effectively used his power to persuade the school and wider community, including paramedics following Lily’s suicide attempt, that the disclosures were lies and a function of mental illness. A wide range of examples of perpetrators manipulating individual victims, the broader family system and social and community networks in order to have access and opportunity to abuse the targeted child victim were noted in this study.

The evident need to disclose repeatedly underscores the challenges in achieving effective interventions, echoing prior studies that emphasise the ongoing struggle survivors face in being heard and believed [35]. This aligns with Tat and Ozturk’s [37] conceptualisation of self-disclosure as a process rather than a one-off event. Findings also confirmed societal barriers such as misconceptions, stigma and stereotypes about child sexual abuse survivors, where participants described being labelled as troublemakers or treated differently as significant barriers to disclosure.

Perhaps the most surprising finding in this study was the reports by the majority of participants (n = 43) that there was a lack of a safe adult for these child victim-survivors to go to and the complexity associated with the absence of a safe parent. Previous research has found that family dynamics can act as an interpersonal barrier where family violence, social isolation and fear of consequences of telling are present [16]. This study extends current knowledge about the complex family dynamics that rendered children unseen and unheard when they tried to tell or, worse, actively silenced. Responses to disclosure were referred to as a retraumatising experience. Unfortunately, even when children and young people did have the words to disclose their experiences, their attempts to disclose often received a negative response. Their abuse was frequently met with disbelief, denial and minimisation or dismissal. In many instances, they were told to be silent, shut up, forget about it or simply move on. Some were turned against, blamed or punished. Some were forced to keep contact with abusers.

Safeguarding children from sexual abuse involves more than enabling the act of disclosure. Safety in this context hinges on how these disclosures are listened to, heard and acted upon. While our findings support scholarship that conceptualises disclosures as a ‘process’ rather than a ‘one-off’ event, our participants clearly articulated that this was due to the persistent failure of family, friends and child-servicing institutions to listen and believe their disclosures. The highest number of first-time disclosures in our sample was, in fact, when victims were children. However, adults failed to hear and believe them, and hence, disclosures were not acted upon until much later in their lives.

Moreover, these findings complement the recent research suggesting that when children and young people feel unsafe, they are more inclined to confide in a friend rather than an adult professional within a child-serving organisation [17, 22]. While the participants in this study did not explicitly state this trend, their experiences indicated that they often lacked access to safe adults to disclose to. Moreover, those they did approach often failed to recognise the signs of sexual abuse or respond in ways that were genuinely helpful.

7. Limitations

The qualitative paradigm adopted for this study offered a context-sensitive, holistic, flexible and dynamic methodology to examine the complexity of child sexual abuse disclosure. As a qualitative study, however, findings cannot be seen to be generalisable, nor can they be compared to other similar studies. In addition, the recruitment strategy employed included support from a select group of partner agencies who purposively invited former service users to consider the opportunity to participate in the study. Those prospective participants who were assessed (by the relevant agency) as having an unacceptable level of risk of harm or high levels of distress that might be exacerbated by being involved in an interview, were not invited to participate. Whilst this was an ethically appropriate criterion for exclusion, it may have resulted in the failure to capture a more diverse data set. In addition, the sample consisted of adult participants reflecting retrospectively on their experiences of child sexual abuse. As such, the memory of such historical cases may have been affected by the passing of time, as shown in much of the review of adult retrospective studies [14, 35]. The sample also largely consisted of women, and therefore, findings may not be generalisable to male victims and survivors (who may not disclose in childhood as often as those in this study). That said, this study offers rich narrative input from 51 victim survivors of child sexual abuse, who each shared the details of their stories. An analysis of this data set has both confirmed and extended knowledge in this critical area. Implications for further research which builds on these findings are outlined below.

8. Implications for Policy and Practice

Current practice guidance, for example, in statutory child protection in Australia, assumes the presence of a simple binary in these situations, that is, a perpetrator or perpetrators and a nonabusing parent (usually the child’s mother). Practice guidance premised on this assumption advises that “Intervention should aim to promote the relationship between the child and the nonabusing parent(s)” [38, p. 9]. This study revealed, however, that children may not, in fact, have a safe, nonabusing person to disclose to and that lack of safety revealed itself in a number of covert and overt ways. Findings suggest the need to consider the ways in which adults (family members, community and professionals) can be empowered and enabled to listen to children when they tell, show children that they have been heard and act in ways that facilitate safety.

Secondly, the implications for practice where younger children and children with communication difficulties are trying to tell about the abuse that they have experienced should be considered. These findings, whilst emerging from a small qualitative study, potentially challenge the prevailing practice wisdom that disclosure is often delayed until adulthood. Disclosures happen during childhood, but no one listens or acts. Further investigation in relation to the knowledge, skill and support requirements for adults and relevant service systems to hear, understand and act is warranted.

9. Implications for Further Research

A large-scale study is required to test the generalisability of these important findings, which will be carried out via a quantitative online national survey in the next phase of this research. In addition, further research is required to develop a greater understanding of the nuance in circumstances where, for example, mothers may have an awareness of the abuse that their child has experienced but feel unable to act on that knowledge. Including the attitudes and behaviours of nonabusing parents will shed light on the impacts of intergenerational trauma and victimisation in the cycle of child sexual abuse and domestic violence. A far deeper understanding of child sexual abuse is required to inform contemporary practice frameworks informing practitioner responses.

10. Conclusion

This paper reports on the findings from qualitative, in-depth interviews with 51 adult victims and survivors of child sexual abuse. The research explored what influences or enables children and young people to disclose their experience of child sexual abuse. It also investigated the barriers to disclosure. Factors influencing disclosure were highly contextual in terms of the individual’s developmental status and wider contextual issues. Enabling factors were overwhelmingly related to the presence of a trustworthy person who saw the child, listened to their story and acted to create safety.

The barriers that children and young people faced when it came to disclosing their abuse were, at times, overwhelming. Time and again, participants spoke of ways in which perpetrators of abuse created and maintained silence. For many, the entrapment within an abusive relationship was complete when the ‘nonabusive parent’ also acted in ways to maintain silence by actively dismissing the child, denying the truth of the story or blaming the child as the source of the problem. Finally, institutions such as police and child protection services were seen to pose substantial barriers to disclosure.

Further research is needed to examine the findings in this study with a view to measuring the possible associations between the range of responses to disclosure and victim survivor safety and well-being. In addition, further review of the way in which service systems surrounding children are designed to work with the uncertainty of children’s early attempts to disclose their abuse is needed. This study found that service responses need to be sensitive to the protection of children’s best interests as opposed to the safety of the institution. Institutions also need to better understand the likely process involved in children’s disclosures, as opposed to seeing disclosure as a one-off event. Finally, it is critical for individuals, families and communities to listen and give weight to the full range of diverse children and young people’s experiences to develop evidence-informed, flexible, tailored and targeted responses to child sexual abuse.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Centre for Action on Child Sexual Abuse (Australia).

Endnotes

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements. However, further information about the data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.