Job Demands and Resources in Relation to Nurses’ Health in Home Care: An Integrative Literature Review

Abstract

Home-care nursing is gaining importance because of the increasing number of people requiring care. Home-care nurses are exposed to high demands, which can have adverse health consequences. This study aimed to conduct an integrative literature review to identify the job characteristics and their relationship with health-related outcomes among home-care nurses. A systematic literature review was conducted using the Cochrane Library, Medline, CINAHL Complete, PsycInfo, PsycArticles, and Psyndex databases. A total of 5510 studies were screened, and the final sample for this integrative review comprised 52 studies. We used a descriptive thematic method to synthesize the data. Our analysis revealed that the most relevant job demands for home-care nurses were work overload, time pressure, fragmented care, sexual harassment and violence, role conflicts and work–family conflicts, and emotional and physical demands. These demands are risk factors for stress; mental, musculoskeletal, and cardiovascular diseases; and the intention to leave the profession. Job resources that positively influenced health outcomes were identified as social support, especially reachability during the shift and room for peer exchange; learning and personal development within the home-care service; provision of feasibility equipment; possibilities to participate in organizational decisions; autonomy to schedule their own work; a promoting leadership style; and sufficient payment. To improve home-care nurses’ job characteristics and thus protect their health, interventions should be taken at the political, organizational, and individual levels.

Summary

-

What is known about this topic

- •

Home-care nursing is becoming increasingly important due to demographic changes

- •

Home-care nurses are exposed to multiple physical and psychological job demands

-

What this paper adds

- •

First integrative overview of job characteristics in home care and health-related consequences for nurses

- •

Job demands such as work–family conflicts, time pressure, travel demands, violence, or working in bending positions negatively affect nurses’ health, leading to stress, burnout, or musculoskeletal diseases.

- •

Job resources such as social support, learning, and personal development, provision of feasible equipment, possibilities to participate in organizational decisions, autonomy to schedule their own work, promoting leadership style, and sufficient payment, positively affect nurses’ health.

- •

It is recommended that nurses’ health be enhanced through human-centered job design, especially with regard to supportive work organization in home-care services.

1. Introduction

Given the increasing demographic changes worldwide, the number of people requiring care is rapidly increasing. Most older adults prefer to stay in their familiar home environments for as long as possible, thereby proliferating the idea of “aging in place.” In Europe, many countries prioritize home care through certain policy frameworks [1]. Not only do older adults receive home care but also do people with chronic diseases and children with disabilities [2]. Hence, the requirement for home care, especially home-care nursing, is predicted to increase [3].

Home care is a complex and widespread practice [4]. Although the term “home care” is understood differently among countries, its basic characteristics are reported as any care provided in one’s own facilities [5]. The term “home-care nursing” refers to the specific nursing practice provided in the patient’s private residence. The activities of home-care nursing services are heterogeneous. De Vliegher et al. [6] distinguished between direct patient care, monitoring (observing patients’ health status and care needs), administration, and psychosocial care.

According to current WHO guidelines, it is crucial to protect nurses’ health by creating safe and healthy jobs [7]. The job demands–resource (JD–R) model is widely used to explain the associations between job characteristics and health-related outcomes [8]. Organizational and job characteristics are subdivided under job resources as “physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the work” and under job demands as “physical, social or organizational aspects of the job” that require sustained physical or mental effort and are therefore associated with certain physiological and psychological costs [9]. Job resources can reduce the adverse effects of job demands in relation to the associated physiological and psychological costs and help reach work goals. Moreover, they stimulate personal growth and promote learning and development [8, 9]. The consequences of persistently high job demands include reduced health due to burnout, or organizational consequences such as turnover [10].

Organizational and job characteristics that rely on the organizational structure and context or refer to the conditions of the required work tasks affect nurses’ reactions [11, 12].

The organizational characteristics of home-care nursing differ from other work environments in the healthcare sector such as hospital settings (e.g., regarding the size and hierarchical structure of the institution). Furthermore, home care includes specific job characteristics, such as working alone, intensive contact with patients and relatives, and the need to constantly adapt to varying spatial conditions. The work environment often includes tight bathrooms or a lack of equipment, which leads to poor body postures associated with musculoskeletal diseases in nurses [13]. Owing to several patient visits per tour, work-related mobility is another attribute of home care related to safety, health, and economic costs [14].

Caring for patients outside a clinical environment means that the influence of occupational health and safety rules is less, even though the home-care setting has been identified as a high-risk industry. On the one hand, the aforementioned characteristics of home-care nursing, such as very close patient contact and working alone, increase the risk of nurses being exposed to violent assaults or being injured due to the domestic and therefore often unsuitable working environment (e.g. pets, tripping hazards) [15, 16]. On the other hand, the employer cannot directly protect employees, for example, through the design of the workplace.

International studies have shown that home-care nursing is associated with mental and physical demands [17–19]. Moreover, there are indications that workload, as well as work-related stress that home-care nurses experience, has increased [20]. Hence, the rate of sickness absence among home-care nurses is higher than in other professions [21]. Empirical studies analyzing the relationships between organizational and job characteristics, health-related outcomes, and psychological work reactions of home-care nurses are available; however, to the best of our knowledge, two reviews exist, but they do not consider current evidence [20] or included only studies of English-speaking countries [22].

Therefore, this review aimed to systematically analyze the job characteristics (job demands and resources) in home-care nursing that affect nurses’ health-related outcomes. The resulting overview provides solid starting points for targeted interventions to ensure human-centered work.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted an integrative literature review. This method summarizes the available empirical and theoretical literature to present a comprehensive understanding of a specific problem and identify factors that are particularly suitable for healthcare [23]. One advantage of an integrative literature review is the possibility of considering different methodologies [24]. This is necessary because of the available scope for the identification of relevant qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method approaches during the initial scoping of the literature in the field of home-care nursing. Quantitative research was predicted to state statistical relationships between job demands and resources on the one hand, and health-related outcomes on the other. Qualitative research would provide insights into nurses’ experiences of work-related stressors and health-related consequences.

2.1. Search Strategy

The Population, Exposure, and Outcome (PEO) framework is a simple and effective method often used for generating search terms for collating relevant materials for a systematic literature review. Based on the research question “Which job and organizational characteristics (E) affect the health (O) of home-care nurses (P)?” search terms were derived (Table 1).

| Population | Exposure | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Home-care service ∗ home healthcare | Work organization | Occupational diseases |

| Home healthcare | Work organization | Occupational health |

| Outpatient care | Job characteristic ∗ | Occupational stress |

| Home-based nursing | Work characteristic ∗ | Physical strain |

| Home-care nursing service ∗ | Job resource ∗ | Psychological strain |

| Home-care nurse ∗ | Job demand ∗ | Work-related illnesses |

| Home health nursing | Work-related stress | Occupation-related injuries |

| Community health nursing domiciliary care | Job-related stress | Work-related stress |

| Home-care agency ∗ | Occupational stress | Job-related stress |

| Occupational-health nursing | Mental stress | Mental stress |

| Physical stress | Mental health | |

| Work stress | Psychological stress | |

| Workplace stress | Strain | |

| Occupational exposure | ||

| Workload |

- ∗Means the truncation of the single words.

In addition, two authors conducted a search for systematic reviews and meta-analyses on job characteristics in home-care nursing to identify and confirm further relevant search terms. The selected terms were checked in the MeSH database from the U.S. National Library of Medicine to verify their relevance and identify additional synonyms and over- and under-terms, if necessary. The search string was first constructed for searching in the Medline database and then gradually adopted for other databases (Supporting 1), taking into account database-specific MeSH terms. By combining important terms and their synonyms from both nursing and occupational health literature, a sensitive and specific search string was created. The final search was carried out on 1 October 2021 and updated on 26 March 2024. The search strategy was developed by two authors and discussed with colleagues in the department.

The following electronic databases were explored to conduct the literature search: Cochrane Library, PsycInfo, PsycArticles, Psyndex, CINAHL Complete, and Medline. Additionally, a manual search of Google Scholar was conducted. To complement the database search, further studies were identified by examining the references suggested in the retrieved literature.

Studies were included in the integrative review if they met the following criteria: (a) Were written in English or German, (b) were published in a peer-reviewed journal, (c) included employed home-care nurses as participants (i.e., student samples were excluded), (d) explored home-care nurses’ job characteristics (job demands and resources) and organizational characteristics, and (e) examined the associations with health-related outcomes of home-care nurses.

The concept of home-care nursing varies across countries. Therefore, numerous terminologies exist, for example, “district nurses” or “primary health-care nurses.” In many cases, different professionals were summarized under one term; for example, “home-care workers,” “domiciliary care workers,” “domestic helpers,” “health support workers,” or “home helps,” rendering it challenging to surmise which profession was studied. Our focus was on the task parameters of nurses as described by Genet et al. [5], which are comparable to the tasks of home-care nurses in Germany; specifically, employed and professional nurses who visited and cared for patients’ health and social needs in patients’ homes. Helpers who stayed with a patient for several hours or lived in the same apartment were excluded from the study. Therefore, no differences regarding their qualifications (nursing assistants, registered nurses, nurses with bachelor’s degrees, etc.) were made. Studies with a focus on professionals whose main task was comparable to counseling, such as “health visitors” or “home visitors” and investigations that explored the experiences of specialized nurses, for instance, those involved with palliative care or mental health, were excluded. Studies that relied on nurses’ experiences with patients suffering from special diseases such as dementia or leukemia were also excluded, as were studies related to semiresidential care, nursing homes, hospitals, or informal caregivers. No restrictions were imposed on publication dates.

2.2. Study Selection

The initial search yielded 6313 results. Of these, 116 records could not be obtained. Using EndNote, 750 duplicates were eliminated. The remaining 5510 references were then screened by title and abstract, and uncertainties regarding inclusion in the study were discussed and resolved. Two authors independently read the remaining 108 studies to verify the inclusion criteria. The interrater agreement, measured with a Cohen kappa of 0.79, can be described as substantial [25]. The few studies that were evaluated differently were discussed until an agreement was reached. Articles were excluded if (a) they focused on the needs of care-dependent people (n = 1), (b) the focus was ostensibly on informal caregivers (n = 6), (c) the target group was not home-care nurses (n = 42), or (d) they did not report any association between job or organizational characteristics and (health-related) outcomes (n = 11). Yet another article was eliminated as the full text could not be obtained.

In addition, a manual search for supplementary articles in Google Scholar and a citation search were conducted, yielding six further publications. A flowchart illustrating the selection process is shown in Figure 1. Finally, 52 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

2.3. Quality Appraisal

Owing to the various types of studies, no homogeneous evaluation of the studies was possible [24]. Thus, the included studies were critically appraised by two authors using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP-Tools) [27], which specializes in different types of studies, and the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool [28]. Given the inclusion of different study types, no scoring system was used [24]. The two tools were also used to assess ethical aspects (e.g., communication with participants, informed consent, approval from ethics committees) and methodological aspects (e.g., fitting of research questions and research approach, observance of confounders, and substantiated interpretation through data). One study was excluded because of methodological ambiguities. Two studies relied on the same database [29, 30]. Ultimately, 52 studies were included in the analysis.

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

The data extraction involved the following steps: data reduction, data display, data comparison, conclusion drawing, and verification [24, 31]. The first author read each study multiple times, took initial notes, and extracted relevant themes regarding the research question. For “data reduction,” a classification system regarding the job demands and resources of home-care nurses was developed (based on Demerouti and Nachreiner [10]). Through “data display” and “data comparison,” a thematic analysis of the primary studies was conducted to identify, analyze, and report pattern themes with data [32, 33]. Emerging patterns in primary studies on home-care nurses’ health were identified and documented. In the last step “conclusion drawing and verification,” the reported job demands and resources as well as the associations between these job characteristics and (health-related) outcomes were compared, related to each other, generalized, and finally aligned with the primary data. This method allowed for the detailed identification of essential themes across different methodologies. Two authors conducted the data analysis, and the intermediate status was discussed in the department.

There is yet no reporting statement available for integrative reviews; therefore, the study results followed the framework of Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) [34] (Supporting 2). This framework was selected because of the narrative structure of our review.

3. Results

A majority of the 52 studies under analysis reported a quantitative design (n = 34), 11 were qualitative, 5 referred to a mixed-method approach, and 2 were literature reviews. The quantitative studies comprised longitudinal (n = 5) and cross-sectional (n = 29) designs.

The studies were conducted in Germany (n = 8), the Netherlands (n = 8), the United States (n = 6), Canada (n = 5), England (n = 4), France (n = 4), Norway (n = 3), Sweden (n = 3), and Switzerland (n = 2), one study each from Belgium, China, Iran, Japan, Finland, Poland, Turkey, Sweden, and Finland, and one study involving various countries (Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, and Slovakia).

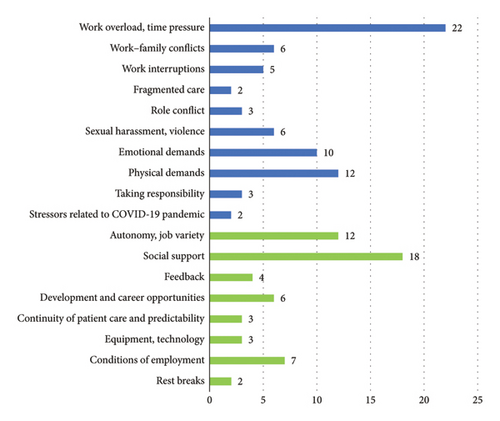

Regarding the analyses of the relationship between job and organizational characteristics and health-related outcomes of home-care nurses, a total of 18 themes, 10 job demands, and eight job resources emerged (Figure 2). The results are presented in Table 2 with separate numbers.

| No. | Author(s), year, journal | Study type | Job resources | Psychological job demands | Physical job demands | Health-related outcomes | Relationship between job demands, resources, and health-related outcomes | Participants or number of studies | Geography | Appraisal tool |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Andersen and Westgaard [29], work | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

• Manual handling of patients |

|

|

138 home-care workers (nurses) | Norway | MMAT | |

| 2 | Andersen et al. [30], Applied Ergonomics | Quantitative-longitudinal questionnaire study |

|

|

• Shoulder-neck pain | • Healthcare workers with low or moderate strain scored significantly lower than the high strain subgroup for physical and mental demands, perceived general tension and shoulder-neck pain |

|

Norway | MMAT | |

| 3 | Arts et al. [35], Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences | Literature review |

|

|

|

|

21 studies | Netherlands | CASP-Systematic-review | |

| 4 | Arts et al. [36], Health and Social Care in the Community | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

• Physical workload |

|

|

474 home helps | Netherlands | MMAT |

| 5 | Bakker et al. [37], International Journal of Stress Management | Quantitative--multigroup analysis |

|

|

|

|

|

3.092 home health nurses | Netherlands | MMAT |

| 6 | Bakker and Sanz-Vergel [38], Journal of Vocational Behavior | Quantitative-longitudinal questionnaire study |

|

• Work engagement |

|

|

Netherlands | MMAT | ||

| 7 | Boniface et al. [39], British journal of community nursing | Qualitative study |

|

• Musculoskeletal pain and diseases | • Physical job demands lead to musculoskeletal pain and diseases | Seven district nurses | England | CASP-Qualitative checklist | ||

| 8 | Büssing et al. [40], Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

• Psychological stress | • Risks by lifting, carrying, positioning, and risk of infection or stab and cut injury, and handling hazardous materials were associated with psychosomatic and physical health risks | Seven hundred and twenty-one home health nurses | Germany | MMAT | |

| 9 | Büssing and Höge [41], Journal of Occupational Health Psychology | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study | • Verbal aggression | • Psychophysical strain and health | • Verbal aggression by patients as predictors of negative psychological outcomes | Three hundred and sixty-one home-care nurses | Germany | MMAT | ||

| 10 | Canton et al. [42], Home Healthcare Nurse | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study | • Organizational safety/security measures |

|

|

|

Seven hundred and thirty-seven registered home health nurses | United States of America | MMAT | |

| 11 | Cheung and Chow [43], International journal of Aging & Human Development | Quantitative-cross-sectional study |

|

• LBIs | • Lacking organizational resources lead to LBIs | Four hundred home health nurses | Canada | MMAT | ||

| 12 | Cloutier et al. [44], work | Mixed-methods |

|

|

|

|

Sixty-six individual and group interviews, 22 observed workdays, and 35 observed multidisciplinary or professional meetings | Canada | MMAT | |

| 13 | Cockerill et al. [45], Research and Theory for Nursing Practice | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

• Adequacy of time |

|

Thirty-eight registered nurses and 11 registered practical nurses | Canada | MMAT | ||

| 14 | Cœugnet et al. [46], Applied Ergonomics | Mixed-methods |

|

• Negative feelings | • Time pressure leads to negative feelings, risk-taking driving, amount of excess speed | Four home health nurses | France | CASP-case control | ||

| 15 | Czarnecka et al. [47], Polish nursing | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

|

One hundred district nurses | Poland | MMAT | ||

| 16 | Doniol-Shaw and Lada [48], work | Qualitative study |

|

|

|

Fifty-five home-care workers | France | CASP-qualitative checklist | ||

| 17 | Elfering et al. [49], Psychology, Health & Medicine | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study | • Appreciation |

|

• Low back pain | • Emotional dissonance was positively related and perceived appreciation was negatively related to low back pain intensity and LBP-related disability | One hundred and twenty-five home health nurses | Switzerland | MMAT | |

| 18 | Evans [50], British journal of nursing | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

• Occupational stress |

|

Thirty-eight district nurses | England | MMAT | ||

| 19 | Fatem et al. [51], International Journal of Community Based Nursing & Midwifery | Qualitative study |

|

|

|

Thirty-three home-care nurses | Iran | CASP-qualitative checklist | ||

| 20 | Flynn and Deatrick [52], Journal of Nursing Scholarship | Qualitative Study |

|

• Isolation from supervisor and other resources |

|

|

Fifty-eight home health nurses | United States of America | CASP-qualitative checklist | |

| 21 | Gershon et al. [53], American Journal of Infection Control | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

• Percutaneous injuries |

|

Seven hundred and thirty-eight home health nurses | USA | MMAT | ||

| 22 | Guo et al. [54], International Journal of Nursing Practice | Quantitative-multicenter cross-sectional study |

|

|

• Job stress |

|

One thousand and fifteen community health nurses | China | MMAT | |

| 23 | Höge [55], European Journal of Health Psychology | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

• Lacking resources |

|

|

Seven hundred and twenty-one home health nurses | Germany | MMAT | |

| 24 | Höge [56], Stress and Health | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

|

Five hundred and seventy-six female home-care nurses | Germany | MMAT | ||

| 25 | Horneij et al. [57], BMC Musculoskeletal disorder | Quantitative-Longitudinal study |

|

• Sick leave |

|

Four hundred and forty-three home health nurses | Sweden | MMAT | ||

| 26 | Jansen et al. [58], International Journal of Nursing Studies | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

|

|

Four hundred and two community-based nurses | Netherlands | MMAT | |

| 27 | Janson and Rathmann [59], Prevention und Gesundheitsförderung | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

• Thoughts of leaving the job | • Difficulties in dealing with health-related information, work-privacy conflicts, and little leeway in the form of breaks and vacation were associated with higher risk of experiencing thoughts of leaving the job | Two hundred and sixty-one outpatient nurses | Germany | MMAT | ||

| 28 | Larsson et al. [60], BMC Musculoskeletal disorders | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study | • Safety climate |

|

|

|

Sweden | MMAT | ||

| 29 | Larsson et al. [61], International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health | Mixed-methods |

|

|

|

One hundred and thirty-three care aides and assistant nurses | Sweden | MMAT | ||

| 30 | Maurits et al. [62], International Journal of Nursing Studies | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study | • Self-perceived autonomy |

|

|

Two hundred and sixty-two registered nurses and certified nursing assistants | Netherlands | MMAT | ||

| 31 | McKinless [22], British Journal of Community Nursing | Literature review |

|

|

Ten primary studies | England | CASP-systematic review | |||

| 32 | Möckli et al. [63], Health & Social care in the Community | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

|

|

Four hundred and forty-eight home health nurses | Switzerland | MMAT | |

| 33 | Mojtahedzadeh et al. [64], International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health | Qualitative study |

|

|

|

|

|

Fifteen outpatient care givers | Germany | CASP-qualitative checklist |

| 34 | Owen and Staehler [65], Home Healthcare Nurse | Qualitative study-Observation study | • Assistive devices and equipment |

|

• Back stress |

|

Thirty-three nursing aides | United States of America | CASP-case control | |

| 35 | Ree and Wiig [66], Nursing Open | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

|

|

One hundred and thirty-nine home healthcare services employees | Norway | MMAT | |

| 36 | Rout [67], Journal of Clinical Nursing | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

|

|

Seventy-nine district nurses | England | MMAT | |

| 37 | Ruotsalainen et al. [68], BMC Health Services Research | Mixed-methods |

|

|

|

|

One hundred and twenty-one practical and registered nurses | Sweden, Finland | MMAT | |

| 38 | Samia et al. [69], Home Health Care Serv Q | Qualitative - grounded-theory |

|

|

• Stress |

|

Twenty-nine home-care nurses | United States of America | CASP-qualitative checklist | |

| 39 | Schilgen et al. [70], Applied Nursing Research | Qualitative - comparative study |

|

|

• Lifting patients | • Stress |

|

Forty-eight home-care nurses | Germany | CASP-qualitative checklist |

| 40 | Simon et al. [71], International Journal of Nursing Studies | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study | • Reward | • Effort, work intensity |

|

• Back- or neck-pain-related disability |

|

2.606 home health nurses | Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovakia | MMAT |

| 41 | Sterling et al. [72], JAMA International Medicine | Qualitative study |

|

|

|

Thirty-three home healthcare workers | USA | CASP-qualitative checklist | ||

| 42 | Tourangeau et al. [73], Journal of Nursing Management | Qualitative study |

|

|

|

• Intention to remain employed |

|

Fifty home-care nurses | Canada | CASP-qualitative checklist |

| 43 | Tourangeau et al. [74], Health Care Management review | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

• Intention to remain employed (ITR) (5 years) |

|

Seven hundred and thirty-two home health nurses | Canada | MMAT | ||

| 44 | Tummers et al. [75], Journal of Advanced Nursing | Quantitative-longitudinal study |

|

• Negative working atmosphere | • Intention to leave |

|

Three thousand six hundred and sixty-one working in extramural care | Netherlands | MMAT | |

| 45 | Vaartio-Rajalin et al. [76], Home Health Care Services Quarterly | Qualitative Study |

|

• Structural factors (barriers to smooth task management | • Weather conditions | • Affirmative or nonaffirmative shifts |

|

Eighteen home healthcare nurses | Finland | CASP-qualitative checklist |

| Burdensome IT programs, unclear division of responsibility leading to ethical problems) | ||||||||||

| • Process factors (Own mistakes, ethical problems, unplanned work tasks, unavailable clients, communication problems) | ||||||||||

| 46 | Van de Weerdt and Baratta [77], work | Mixed method-ergonomic study- |

|

|

|

|

Eight nurses, seven nursing aides, three coordinating nurses, and three secretaries | France | MMAT | |

| 47 | Van de Weerdt and Baratta [78], Production | Quantitative-longitudinal Ergonomic study |

|

|

|

|

Forty-five home healthcare workers | France | MMAT | |

| 48 | Vander Elst et al. [79], nursing Outlook | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

|

|

Six hundred and seventy-five home healthcare nurses | Belgium | MMAT | |

| 49 | Wendsche et al. [80], International Journal of Nursing Studies | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study | • Collective rest breaks (RBs) | • Turnover |

|

Five hundred and ninety-seven registered nurses in home care and nursing homes | Germany | MMAT | ||

| 50 | Xanthopoulou et al. [81], Journal of Managerial Psychology | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

|

|

Seven hundred and forty-seven home health nurses | Netherlands | MMAT | |

| 51 | Yamaguchi et al. [82], International Journal of Nursing Studies | Quantitative-cross-sectional comparative study | • Job control | • Work–family conflict | • Intention to leave | • Low job control predicted the intention to leave | Four hundred and eight home healthcare workers | Japan | MMAT | |

| 52 | Yurtsever and Yilmaz [83], Africa Journal of Nursing & Midwifery | Quantitative-cross-sectional questionnaire study |

|

|

|

|

Seventy-one home health nurses | Turkey | MMAT | |

3.1. Job Demands and Health-Related Consequences

3.1.1. Work Overload and Time Pressure

Time pressure and work overload were identified as two particularly stressful job demands for home-care nurses in 22 studies (Table 2 numbers: 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 13, 14, 16, 18, 21, 22, 24, 26, 36, 37, 38, 39, 42, 46, 47, 48). Home-care nurses must deal with a highly quantitative amount of work at a given time. They are in charge of caring for several patients within a short timeframe because most patients need support during morning hours [40]. The time required depends on patient factors such as the need for care; nurse-related variables such as age, training, and practice time; and the number of patients to be cared for per tour [45].

These time constraints are influenced by the way home-care services arrange the nurses’ visiting rounds and further, in a superordinate context, by government regulations due to the fixed duration of working tasks (e.g., nursing charge). One root cause of time pressure is seen in the underestimation of the duration of working tasks and particularly of unpredictable follow-up tasks [44, 46]. In addition to time constraints resulting from tight schedules of the nursing rounds, the subjective feelings of uncertainty about the requirements and duration of care of the subsequent patients to be visited on a given shift contribute to the experience of time pressure [46]. Furthermore, documentation and other non-nursing tasks add to work overload [54, 69, 73].

Time pressure has several consequences for nurses. It leads to stress [29, 38, 50, 68], risky driving [46], negative feelings [46, 78], and feelings of burnout [58, 79] and is associated with emotional irritation [56]. Another consequence of time pressure and work overload is that nurses work overtime, which in turn has negative impacts, such as increasing the risk of percutaneous injuries [53]. Time pressure leads to a reduction in care time per patient and fragmentation of care work [48]. High mental demands are expressed in the feeling of having too much to think about, worrying about making mistakes, having to make quick decisions, dealing with unexpected situations, and coherence with perceived general tension, which leads to shoulder, neck, and low back pain (LBP) [30].

Consequently, nurses must focus on the technical aspects of care by shortening the relational parts. This in turn affects nurses’ physical and mental well-being (i.e., emotional exhaustion) [44, 48] and increases the duration of sick leave [44]. Finally, because of the nurses’ internalized duty to provide qualitative care, they tend to work (unpaid) over time, resulting in a doom loop.

3.1.2. Work–Family Conflicts

Among the included literature, six studies reported work–family conflicts among home-care nurses (17, 18, 24, 27, 32, and 51). These conflicts occurred when aspects of one’s job interfered with family-related responsibilities. For home-care nurses, a negative work–family culture in a home-care service, such as missing possibilities to balance work-related tasks with the responsibility of the family, is a significant predictor of the intention to leave their job [59, 82].

Furthermore, work–family conflicts are associated with emotional exhaustion and stress [50, 63]. The risk of experiencing work–family conflicts appeared higher when nurses had children under the age of 3 years [56].

3.1.3. Work Interruptions

Of the included studies, five reported interruptions while working with patients or documenting after the shift (8, 12, 36, 37, and 38). This job demand was positively associated with stress and higher mental load [44, 67–69].

3.1.4. Fragmented Care

Two studies mentioned that fragmented care is a significant job demand for home-care nurses (12, 16). Economic pressure on home-care nursing has increased in recent years [44, 48]. The consequence for home-care services is rising pressure to work more efficiently and save money, while nurses are faced with a higher workload, namely, to care for more patients without having more time to spare. As a result, it is not uncommon for services to develop tailored principles of dividing care work into separate tasks with scheduled times, which are experienced as fragmented care [48]. Consequently, nurses reduce the relational aspects of care to fulfill at least the technical aspects [44]. The lack of time for unpredictable tasks or patient needs leads to difficulties for nurses [48]. Increased workloads and the resulting fragmented care increase the risk of health issues such as musculoskeletal and psychological problems [44].

3.1.5. Role Conflict

Home-care nurses’ role conflicts were discussed in three studies (3, 4, and 38). Nurses are in a special position among case managers, patients, and relatives; thus, they must level the needs and expectations of each side by being loyal to all [69]. The professional goal of providing care based on ethical values and responsibilities is a part of the nurses’ self-concept. This may conflict with the expectation that case managers adhere to time constraints [69]. Role conflict is linked to stress among home-care nurses [35, 36, 69].

3.1.6. Sexual Harassment and Violence

Sexual harassment and violence were claimed by six studies to be urgent topics in home-care nursing (5, 9, 10, 21, 39, and 50). Working alone without the protection of an institutional framework increases the risk of sexual harassment and violence against home-care nurses [37, 41, 42, 53, 81], especially for migrant nurses [70]. Home-care nurses are exposed to verbal abuse, the threat of physical harm, damage to vehicles owned by them, or physical assaults, of which verbal aggression is predominant [41, 42, 53]. Risk factors for violent exposures were stressful household conditions such as unsanitary conditions or blurring of work and personal time, slipping trips and fall hazards, demanding clients, aggressive pets, drug abuse, racial discrimination, and neighborhood crime [42]. In addition to other consequences, exposure to work-related violence is a risk factor for percutaneous injuries [53], low job satisfaction, and intention to leave [42].

Furthermore, aggression or patient harassment correlates with negative psychological strains such as irritation, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization [42] and is a strong predictor of emotional exhaustion and cynicism [81].

3.1.7. Emotional Demands

Emotional demands were identified by 10 studies as a relevant job demand (3, 6, 14, 17, 24, 31, 42, 47, 48, and 50). Caring for patients in need over a long period leads to job satisfaction because the relationship between nurses and patients can develop over time [73]. On the other hand, emotional demands, which are understood as “lack of self-belief, feeling unable to yield enough care, having a bad conscience, emotionally demanding patients and being too involved in patients’ situations” [30] can occur.

Emotional demands can be challenging for nurses [22, 38, 49, 78, 81] and affect their health. They are strong predictors of exhaustion, burnout, and cynicism [79, 81]. In particular, emotional dissonance—dealing with the need to display emotions that one does not feel—is demanding. Elfering et al. [49] and Arts et al. [35] showed that emotional dissonance influenced LBP intensity and LBP-related disability beyond other predictors.

3.1.8. Physical Demands

Physical demand is a well-documented requirement of home-care nursing, as reported in 12 studies (2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 11, 17, 25, 34, 40, and 42). Home-care nursing is characterized by physically high demanding tasks such as heavy lifting and transferring, unpleasant postures, physical layout of the workplace, lack of necessary equipment, and mobility and travel demands [30, 36, 37, 39, 41, 65, 71, 73]. Physical demands are higher in home-care nurses who are confronted with time pressure and struggle with new work procedures (e.g., personal digital assistants).

Arts et al. [35] confirmed the negative effects of physical demands on health (musculoskeletal and cardiovascular diseases). Accordingly, home-care nurses report high levels of shoulder and neck pain, lower back pain, and lower back injuries associated with physical demands [36, 39, 43, 49]. Physical demands were associated with disability [71], whereas perceived physical exertion and existing low back disorders were associated with a higher risk for prolonged future sick leave [35, 57].

3.1.9. Taking Responsibility

In the literature, three studies dealt with the different levels of responsibility linked to the different qualifications of nurses working in home-care nursing (4, 26, and 37). While nurse assistants support daily life activities (eating and bathing), registered nurses have complex nursing duties and medical tasks and are more in charge of care plans and organization [36, 68], with minor international variations in the designations. Empirical findings show that strain and burden increase with increasing responsibilities [36, 58]. Evidence suggests that job characteristics such as time pressure, task variety, or feedback culture, and health outcomes such as the level of emotional exhaustion differ depending on nurses’ qualifications and responsibilities of registered nurses [36, 58]. On the one hand, more highly qualified nurses are more stressed and feel emotionally exhausted more often than less qualified nurses. On the other hand, job satisfaction appears to increase, particularly due to the increasing variety of tasks with increasing responsibility [36].

3.1.10. Stressors Related to the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic aggravated home-care nurses’ job demands (33, 41). Stressors experienced by nurses were strict hygiene regulations, insufficient or contradictory information and recommendations, fear of infection or infecting others, as well as experiencing patients’ sadness, fear, loneliness, and feelings of invisibility despite being on the frontlines of the pandemic care service [64, 72]. Home-care nurses reported a higher workload and emotional demands during the pandemic [64].

Reactions to these stressors included depressive symptoms, anxiety, fear of the consequences of the pandemic, stress, and impaired individual performance, while important resources to cope with these additional burdens were team spirit, communication, and peer support [64, 72]. The studies found emphasize the drastic effect of the pandemic on working conditions and the resulting strain on home-care nurses.

3.2. Resources and Health-Related Consequences

Job resources are important for buffering the relationship between job demands and negative (health) outcomes. The following resources were identified through our review:

3.2.1. Autonomy and Job Variety

In the literature, twelve studies examined autonomy and job control as crucial resources for home-care nurses (5, 15, 20, 26, 30, 36, 38, 42, 43, 44, 48, 50, and 51). Job autonomy is described as authority over work decisions and skill discretion [11].

If home-care nurses experience more autonomy, they are more engaged in their work and are less likely to leave the healthcare sector [62, 75, 82]. Furthermore, autonomy is positively associated with work engagement [62, 76, 79], which acts as a buffer between job demands and burnout [76, 81]. In contrast, reduced autonomy is a common stressor among nurses [69] and leads to cynicism [32].

Closely related to autonomy is variety in job tasks. Having a greater variety of tasks decreases the risk of burnout [58] and is positively related to job satisfaction [58, 67]. Applying a variety of skills within the job and working with various clients positively influences home-care nurses’ intentions to remain employed [69, 74].

3.2.2. Social Support

Another resource for home-care nurses is social support, highlighted in 18 studies (3, 5, 6, 12, 14, 16, 19, 20, 24, 26, 29, 32, 35, 39, 42, 44, 45, and 52). Social support is described as receiving help and support from colleagues or supervisors and is found to protect nurses from burnout [37, 58, 63, 76, 81] and impede job quitting. Superior–subordinate relationships, in particular, play an important role in maintaining nurses’ work engagement and preventing negative health-related consequences [35, 55, 66, 70, 73, 83].

Support from supervisors (e.g., via telephone) ensures the feeling of being part of an organization and therefore provides a safety frame for nurses who are alone during the shift [46, 52]. This is essential, particularly when unpredicted events affect a patient’s health [51, 76].

Larsson et al. [61] found that good communication and cooperation within home-care teams may positively impact safety. However, due to the single working situation in home-care nursing, there are only a few opportunities to provide social support via group meetings, handovers, or training [44]. The reduction in such meetings due to economic pressure reinforces nurses’ isolation [48] and increases their health risks [44].

3.2.3. Getting Feedback

Four studies demonstrated the importance of feedback as a job resource for home-care nurses (4, 6, 26, and 32). Accordingly, frequent feedback from supervisors reduces the risk of burnout [36, 37, 58, 63]. Möckli et al. [63] reported that feedback, for example, conversations about the quality of work with colleagues or supervisors, contributes the most to the social support that nurses are engaged in.

3.2.4. Development and Career Opportunities

Another job resource in home-care nursing is the opportunity to receive additional training to develop one’s skills, which was examined in six studies (22, 27, 42, 44, 48, and 50). Insufficient development and career opportunities are significant risk factors for job stress [54] and intention to leave a job [59]. Guo et al. [54] indicated that nurse managers should promote and benefit from career opportunities for home-care nurses.

3.2.5. Continuity of Patient Care and Predictability

Furthermore, three studies highlighted continuity of patient care as a relevant resource for home-care nurses’ health (42, 54, and 46). Long-term relationships and positive interactions with patients are sources of satisfaction because they contribute to the meaningfulness of work [73, 76, 78], which in turn motivates nurses to stay in their jobs [74]. The prerequisite for experiencing this meaningfulness of work is continuity of care. If patients switch daily and the required care work is unpredictable, additional stress occurs [76].

3.2.6. Equipment and Technology

Three studies analyzed the potential for using technological advice in home-care nursing (20, 42, and 45). They found that documentation via smartphones has the potential to facilitate work in home-care nursing to make it more efficient. Available equipment is linked to nurses’ positive emotions, and problems with information technologies can be a source of stress [73, 76].

3.2.7. Conditions of Employment

Employment conditions were discussed in seven studies (15, 22, 23, 37, 42, 43, and 52). A crucial stressor for home-care nurses is low wages [47, 54, 73, 74]. Consequently, satisfaction with pay, income stability, and the opportunity to work full-time lead to the intention to stay employed [74, 83].

3.2.8. Rest Breaks

Two studies addressed the significance of resting breaks in home-care nursing (27 and 49). The opportunity to rest and gather new energy during a shift is an important strength for nurses in outpatient settings [80]. In particular, shared breaks are associated with nurses’ retention in the organization [80], whereas less participation in designing and planning breaks for home-care nurses is related to thoughts about leaving the job [58].

4. Discussion

This review investigated the job characteristics of home-care nursing in relation to nurses’ health. We identified 18 themes, divided into job demands and job resources.

Not only were classical job demands such as work overload, work–family conflicts, work interruptions, and physical or emotional demands elaborated, but specific demands for home-care nursing, such as fragmented care, role conflicts, sexual harassment, and violence were also analyzed. Due to regulations in home-care nursing work, overload and time pressure that lead to fragmented care appeared to be common work stressors with negative health-related consequences. Fragmented care—that is, determined single tasks—might hinder the autonomy that home-care nurses deserve from home-care organizations. Tummers et al. [12] stated that high decision authority for nurses implies “performing several kinds of tasks (a whole ‘product’) instead of only one specific part of it.” This is in line with the job characteristic model of Hackman and Oldham [84], which designates task identity—responsibility for a complete work process instead of only a part of it—as a crucial factor for work motivation. This positive job characteristic appears to be inhibited by an increase in fragmented care in home-care nursing.

Work–family conflicts are associated with emotional exhaustion, stress, and the intention to leave the profession [38, 63, 82] although balancing work and family issues seems easier in home-care nursing than in other nursing settings. Furthermore, role conflicts such as balancing the economic expectations of supervisors and the mission to provide professional care to patients play an important role in the strain experienced by home-care nurses. In this context, role conflicts in nursing might have a moral dimension, which could be linked to moral distress, the “painful feelings and/or the psychologic disequilibrium that occurs when nurses are conscious of the morally appropriate action a situation requires but cannot carry out that action because of institutionalized obstacles” [85, 86]. Physical and emotional demands are inherent in home-care nursing and are connected to threats to nurses’ health. Working with patients with musculoskeletal pain is part of everyday work, but the needs of patients often seem to be more important for nurses [39]. It is important to strengthen nurses’ health literacy to counteract their self-perception of working in pain [58]. Moreover, different measures are necessary to support home-care nurses in coping with these demands. Being prepared and receiving training to handle emotionally demanding situations with patients can be an organizational strategy to help home-care nurses cope with and reduce uncertainty [46, 49]. Moreover, leisure time and activities seem to be important resources for detaching from emotionally demanding tasks [56].

Regarding job resources, well-known characteristics, such as autonomy and social support, were found to promote nurses’ health. In particular, reachability during the shift and ensuring space for peer exchange, opportunities to develop within the nursing service, provision of feasible equipment, possibilities to participate in organizational decisions, autonomy to schedule their own work (including part-time or full-time employment), and sufficient payments seem to be significant resources. Additionally, the leadership styles of case managers and supervisors play an important role in reducing or increasing work constraints [44]. However, specific factors of home-care nursing, such as continuity of care, are also important resources for nurses’ satisfaction and health [76].

4.1. Limitations

This study has some limitations that must be considered when interpreting our findings. Home-care nursing is a vast and complex field, and international comparisons are limited because of different organizational characteristics and healthcare systems. Thus, job demands, job resources, and health situations of home-care nurses differ among countries. For instance, local aspects such as gun violence, may be a crucial problem and threaten nurses’ health in some areas of the United States, whereas it is not a major issue in other countries. Furthermore, the underlying qualifications of home-care nurses and their career opportunities may differ significantly between countries and influence job demands, job resources, and nurses’ health. Accordingly, the included studies observed various types of employments, levels of education, and task autonomy. Furthermore, the studies confirmed the diversity within home-care nursing; for example, specialized nurses in palliative and mental health settings may face different job demands and resources.

Another limitation is the possibility of missing relevant studies, although utmost care was taken to identify them. As only studies written in English or German could be included, articles from predominantly Western countries were reviewed. One strength of this study is that Whittemore and Knafl’s [24] methodological cues concerning integrative reviews were considered.

This review aimed to provide an overview of the job demands and resources of home-care nurses and their related health consequences. To consider this situation in relation to other professions or nursing settings, it is necessary to review comparative studies.

5. Conclusions

Considering the eighth United Nations Sustainable Development Goal of decent work and the reported job demands and resources of home-care nurses, improving their job characteristics and promoting their health as much as possible are crucial.

This can be implemented at various levels. The framework conditions for home-care nursing must be addressed at the political level. Depending on the national organization of home-care nursing, it seems necessary to increase the refinancing of care interventions to provide more time for holistic or person-centered care rather than fragmented care. This could reduce work-related stress and decrease time pressure, thus providing sufficient space for home-care nurses to tasks [54]. Higher wages could increase the attractiveness of the profession and, thus, attract young people to home-care nursing to counteract personnel shortages in the long term. However, political regulations should permit and promote new attempts to organize home-care nursing. For example, self-organized teams, such as the Buurtzorg model [87], could increase task autonomy and the feeling of having influence, which is seen as an important resource [68]. Self-organized teams may also help prevent fragmented care, which leads to stress for home-care nurses. However, certain prerequisites, such as the possibility of more flexible service billing and the availability of appropriately qualified personnel, must be met for the introduction of new models.

Interventions at the organizational level could help achieve the goal of human-centered work (e.g. Nielsen and Noblet [88]), even if government regulations cannot be changed overnight. The first step in identifying the most urgent need for change in organizational and job characteristics can be taken by risk assessment [7]. The resulting interventions could include the monitoring of administrative tasks [79] or optimizing tour planning by considering the amount as well as the complexity of patients’ care needs. Strengthening resources might amplify social support and the opportunity to participate in decisions such as the allocation of patients and the planning of nursing rounds [79]. Moreover, scheduling work hours on their own could prevent work–family conflicts for home-care nurses. Ensuring a safe climate, for example, by providing cell phones, implementing security escorts if necessary, and encouraging and accompanying home-care nurses, might prevent violence exposure. In addition, the leadership style should be chosen deliberately because it is not only crucial for the health-related outcomes of home-care nurses but also for the quality of care [89].

In addition to these situational preventive measures, behavioral interventions of home-care nurses at the individual level can be strengthened. For instance, psychological techniques that reflect the psychological border between work and family life might prevent work–family conflicts [56]. Strengthening coping strategies with cognitive-behavior training, stress management, mindfulness-based programs, or team-based support groups can reduce nurses’ emotional exhaustion and burnout rates [90] and may be effective for nurses in home care. Although some design needs and related interventions for home-care nursing are already available, more research is needed. One promising approach is a realistic evaluation that considers in addition to theoretical mechanisms social and political aspects. Intervention studies should consider the heterogeneity of home-care nursing (e.g., psychiatric and intensive home-care nursing).

However, in addition to the need for intervention studies, there are also fundamental questions regarding job demands. For instance, it is necessary to clarify how role conflicts in home-care nursing are linked to moral distress because of the possibility of construct overlap. Therefore, the underlying situations that lead to moral distress as a risk factor for home-care nurses should be investigated in detail, considering the growing need for home-care nurses, to maximally enhance their quality of work and life.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The German Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health granted the authors’ research support during this study (Project No. F2521). Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our colleagues of the section “Designing Service work” (Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health) for their manyfold support throughout the process of doing this research and preparing the manuscript. Furthermore, we acknowledge Editage (https://www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Supporting Information

The search strings used (Supporting 1) and the ENTREQ checklist are available as Supporting (Supporting 2).

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this integrative review. Data sharing is therefore not applicable to this review.