Consensus Building Using Modified Delphi Panel and Nominal Group Techniques for Social Prescribing Intervention in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Abstract

Background: Health interventions have been prioritised worldwide to curb the growth and life impact of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Social prescribing (SP), as a complex health intervention, has shown promise in producing positive outcomes. This study aims to establish an expert consensus on a model and SP intervention’s multicomponents to empower self-care and health literacy in T2DM patients.

Methods: A descriptive design using two consensus-building techniques took place between June and September 2023. The modified nominal group technique (NGT) was used to reach a consensus on the SP intervention model with 12 experts, who participated in two online meetings and voted on a scale of 1–9. In addition, a modified Delphi panel with 10 experts in two online rounds to reach a consensus on the intervention’s multicomponents, who rated the categories of the intervention on a Likert scale of 1–5. Consensus was reached when an agreement level ≥ 75% was obtained. The data were analysed via descriptive analysis, and the consensus level was calculated based on the mean, standard deviation and percentage.

Results: Using the modified NGT, the experts reached a 93.52% consensus on the final model flowchart. In the modified Delphi panel’s first round, 27 original interventions were evaluated. In the second round, one was removed because of low agreement, six were revised, and five new ones were added based on participant feedback. A consensus was achieved on 30 interventions across the six categories (cross-cutting intervention components, physical activity, nutrition, medication management, self-monitoring and well-being).

Conclusions: Both consensus techniques ensure that the SP model and these interventions meet the person’s needs and the community it serves. They allow a better understanding of self-care and health literacy strategies, contributing to future health programs and policies for more efficiently managing T2DM.

1. Background

The burden of living with long-term diseases such as Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and its complications is growing dramatically worldwide [1, 2]. Owing to its heterogeneity and multifactorial nature, a complex continuum of care, including diet management, physical activity, self-monitoring and medication adherence, is needed [3, 4]. It requires individuals to take an active and ongoing role in their self-care [5, 6] and make behavioural changes that allow them to improve the management of their condition. Additionally, they must develop health literacy skills to effectively comprehend written and spoken health information, use digital tools and health technologies and navigate health systems to access necessary services [7]. Emphasised as having a major role in improving self-management, adherence to therapeutic regimens and reduced complications, behaviour change theories such as the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) framework are used in the health intervention design and implementation [8–10]. This study adopts the core COM-B model of the BCW, which facilitates the development of health interventions aimed at behaviour change, addressing key factors such as capability, motivation and opportunity that can hinder behaviour change [10]. It also incorporates, as a resource, behaviour change techniques that were used as support tools for informed decision-making and to encourage people to adopt new habits [11].

The numerous challenges imposed by T2DM can lead to feelings of overload, stress, anxiety or even depression [12]. Although recognised as a public health concern, efforts in recent decades to reduce its incidence, prevalence and impact on quality of life and well-being have met with limited success. The World Health Organisation (WHO) accentuates key points in the prevention and promotion of T2DM management, through the conception and development of integrated health interventions in primary healthcare with the collaborative involvement of stakeholders and people living with diabetes [13].

Social prescribing (SP) has been highlighted for its role in an interconnected response in preventing and managing noncommunicable diseases, such as T2DM, through activities developed by the voluntary and community sectors [14–16]. Among the different definitions, SP can be defined as a complex intervention that, through community referrals between health professionals and social prescribers, links patients to different nonclinical activities in the community that aim to improve health and well-being outcomes [17]. According to previous studies, from a holistic perspective, the individual needs of T2DM patients are positively related to quality of life, mental and social well-being (depression, anxiety and loneliness), metabolic control (based on HbA1C levels), a reduction in sedentary lifestyles and cardiovascular risk by reducing weight, abdominal circumference and cholesterol levels [16, 18–24]. Broadly implemented across different countries but with several pathways between contexts and stakeholders, heterogeneous intervention components and diverse-related outcomes exist [25–27]. To address the following research question—which is the most suitable model and multicomponent of a complex SP intervention to enhance self-care behaviours and health literacy in patients with T2DM?—a study was conducted using two consensus techniques to identify and refine the optimal SP model and its multicomponents.

Structured and systematised consensus techniques, such as the nominal group technique (NGT) and Delphi panels, are essential for bridging the gap between research findings and practical application in healthcare, ensuring that evidence-based insights are effectively integrated into clinical practice [28]. They are the most widely used consensus techniques in medical and health research [29, 30]. Traditional consensus techniques have been modified to optimise their structure, such as the number of rounds or delivery modes, making them more flexible, dynamic and suited to the needs of both the research and participant groups [31]. Whereas the NGT typically begins with a brainstorming session where participants share their ideas on a theme, in this study, a systematic literature review was carried out as an initial step to identify SP models within the context of T2DM [26]. A modified NGT used in the discussion of the model, provided an open, structured forum for discussion, encouraging each participant to reflect on and share their perspectives. It enabled prioritisation of key elements, fostering agreement on complex aspects of the model [31]. The Delphi panel originally involved in-person meetings and began with open-ended questions, evolving into a structured, iterative process with multiple rounds and controlled feedback [28, 29]. A modified online Delphi panel was conducted, involving rounds of questionnaires and controlled feedback to discuss and analyse the design of the proposed intervention components based on the literature review [26] and an advisory group. This modified Delphi panel was chosen to provide a flexible but rigorous framework for collecting expert input, ensuring balanced contributions, minimising the influence of dominant voices on the expert panel and supporting a more equitable consensus-building process [29, 30]. The modified Delphi panel facilitated an organised systematic approach, allowing experts to prioritise intervention components, provide feedback and reach a supported consensus on the multicomponent intervention [32, 33]. However, this consensus technique was not chosen to explore the more suitable SP model because it is less interactive due to its asynchronous, questionnaire-based structure, losing the opportunity to explore nuances or clarify points in real time, which can limit the depth and fluidity of responses [32]. Using structured methods collects the expert’s opinions and systematically organises the individual ideas and comments that emerge in a group [30]. Composed of heterogeneous expert groups during consensus building, they can capture different backgrounds, experiences, needs, concerns and perspectives. By leveraging the strengths of both consensus techniques, we aim to develop an SP model, and a multicomponent intervention grounded in expert consensus.

2. Methods

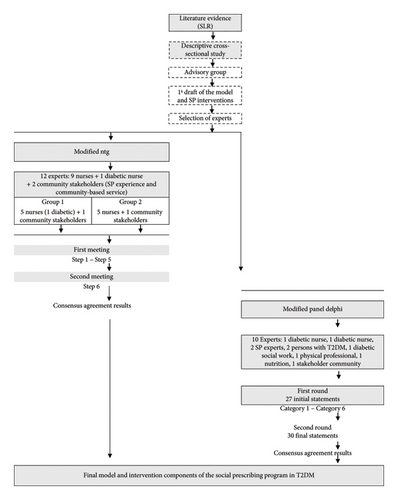

Due to the limited information available, an initial systematic literature review on the effectiveness of SP interventions in achieving health outcomes for T2DM patients was conducted. This review also helped identify the existing SP models, as well as the providers and facilitators involved [26]. A descriptive cross-sectional study was subsequently carried out to identify the specific self-care needs of the target population [34]. Based on evidence from the literature and the identification of T2DM individual needs, the research team developed a preliminary design of the SP model between primary healthcare and the community and the SP intervention multicomponents in T2DM patients. Following a person-centred approach and recognising the importance of early involvement of the person and communities, a diverse advisory group was engaged to discuss face-to-face and coproduce the future SP T2DM intervention collaboratively [35]. The contents of the different intervention categories were based on evidence from the literature and international recommendations for self-care in T2DM [36–38]. Once the first draft of the model and components had been planned, we used a modified NGT and a modified Delphi panel for four months developed remotely, between June and September 2023 (Figure 1). The NGT was used as an initial step to facilitate open online discussion among experts, allowing for collaborative brainstorming and prioritisation of key elements in the model. Following the NGT, a modified Delphi panel with a different sample of NGT was conducted to refine the specific components of the intervention. The experts that joined consensus groups were characterised by their heterogeneity, knowledge in the discussion areas or context, and contributions from different perspectives (as users and or providers) [39].

3. Study Design

3.1. NGT

NGT, a systematic and organised technique, uses nominal groups of 9 and 12 experts in the field to reach a consensus, led by a facilitator who uses a well-defined structure in the session’s advanced [39, 40]. This consensus technique was chosen because it facilitated independent discussion, giving each participant an equal opportunity to share their perspective and vote individually, ultimately reaching a consensus. Group meetings provided space to explore, refine and collaboratively shape ideas, supporting the development of new interventions [41]. The 12 invited expert panels were divided into two small groups of six participants. The two online sessions lasted 2 h via Microsoft Teams®, and the second session occurred 3 weeks after the first. Each session was recorded and saved in one drive with access only to the research team. A trained facilitator from the research team led the sessions to ensure a structured, balanced, and efficient debate between the participants. The facilitator’s experience in guiding and conducting group dynamics, encouraging equal participation from each participant, made it possible to keep the focus on the defined objectives. The experts were asked to vote anonymously on the relevance of each step using a Likert scale between 1 and 9. In Stages 1–3, the experts conclude that the stage is not indicated (very low agreement); in Stages 4–6, the expert has doubts about the stage (low agreement); and in Stages 7–9, the expert feels that the stage is indicated (agreement) [40]. Voting was used inside the Microsoft Teams®, the Polly® engagement application that captures the participant’s feedback in real time. All the parts of the model discussed were accepted as a consensus when the answers obtained a score ≥ 75%. If a rating ≥ 75% was not achieved at the two planned meetings, an analysis would be carried out based on the participants’ comments and proposed for further discussion by the group of experts until a consensus was reached.

3.2. Delphi Panel

The Delphi panel, a method of successive questionnaires interspersed with controlled feedback of opinions, aims to reach a consensus among experts on complex and wide-ranging topics [32, 33, 42]. The questionnaire was sent online and was divided into two parts, with clear instructions on how to fill it. The first part was dedicated to characterising the expert panel, and the second part to the intervention component categories built according to each domain of the SP intervention [26, 27]. SP intervention multicomponent was drawn up based on the person’s T2DM needs, the goals for T2DM self-management [37] and the COM-B model of the BCW [10]. The COM-B model makes it possible to understand the factors that facilitate or hinder the adoption of a desired behaviour, identifying barriers related to physical or psychological capacity, physical or social opportunity, or automatic or reflexive motivational order [10]. With this understanding and the use of appropriate Behaviour Change Techniques, it is possible to create more effective interventions to achieve the desired changes in behaviour [11]. All the categories were designed to create the opportunity to involve and empower the person with their T2DM self-care and to improve health literacy. Each expert was asked to express their level of agreement or disagreement via a five-point Likert scale (1—Strongly disagree, 2—Disagree, 3—I do not agree and I do not disagree, 4—Agree, 5—Strongly agree), with the option of open-ended questions. Rounds were planned until a level of agreement ≥ 75% was reached on each statement. Statements that did not get this level of agreement or that after analysis of the comments were considered important to be integrated, were modelled and moved on to the next round. After the results analysis was obtained, an email was sent to the participants with feedback from the previous round and a new link to a Google Forms questionnaire to participate in the next round. This approach allowed us to gather diverse perspectives, gradually building consensus among experts on the essential components of the intervention, while minimising the influence of any single participant.

3.3. Participants and Sample Size

The two consensus techniques used, the NGT and the Delphi panel, were employed with distinct sample groups for building the consensus of the complex SP intervention. Each selected expert received an invitation letter by email with an explanation of the study and a link to the NGT meeting using Microsoft Teams® or a link to a Google Forms questionnaire for the Delphi panel with informed consent. For NGT, a convenience sample of 12 experts was recruited. The experts were organised into two groups: the first group included five nurses and one community stakeholder from a community-based service and a member of the advisory group, while the second group comprised four nurses, one nurse with T2DM and a member of the advisory group, and one community stakeholder with experience in SP. In health research, different expert panels, such as clinical and nonclinical professionals, stakeholders, researchers and patients, were considered relevant and important for addressing Delphi panels [43]. For this Delphi panel, a heterogeneous group of experts participated: two clinical professionals with expertise in diabetes mellitus (with one also living with T2DM); two international clinical professionals with expertise in SP; one professional representative from the areas of clinical nutrition, social work (also living with the disease), physical education, sports and community partners (stakeholders); and two T2DM patients. Nurses were selected based on their expertise in primary healthcare, community health and diabetes, with two nurses, one in NGT and the other in the Delphi panel contributing with dual perspectives as both a diabetes specialist and a person living with the condition. Community stakeholders were invited, as representatives of the context and their insights into the local community context and for their experience in SP. The nonclinical professionals were recruited based on their working experience with people in the community in the different domains of self-care behaviour in T2DM. Two T2DM patients and two clinical and nonclinical professionals were invited to participate, able to give their perspectives as people who live with the disease daily and as future users of the intervention. All participants provided informed consent and agreed to participate.

3.4. Patient and Public Involvement

Involving the person in their care process and the community in building health programs is key to ensuring their relevance, effectiveness and long-term success [44]. Patients and community stakeholders bring unique experiences, providing essential information about the practical challenges and needs of those directly affected by health programs [44, 45]. In this context, people with T2DM, community partners, clinical (nurse and general practitioner) and nonclinical professionals were invited to participate as an advisory group, for the model and the intervention component coproduction. A preliminary study was conducted to understand the person’s needs in different areas followed by mapping the responses that voluntary and community sectors could offer in the community context. After a systematic review of the literature, and knowledge of the needs and activities provided by community partners, the co-construction of the model and its components began. This study used consensus techniques to establish an active partnership between T2DM patients, community stakeholders and a multidisciplinary team of experts in diabetes care, social services, nutrition, physical activity and community. This involvement ensures that interventions are tailored to real-world concerns, promoting a patient-centred approach with a coproduced health intervention. Previous studies have shown that community involvement in the development of interventions is crucial for adherence, retention and better health outcomes [35], promoting active and transparent collaboration and giving the person a leading role in managing their health [46]. To ensure engagement and gather diverse perspectives, two patients with T2DM, one clinical professional and one nonclinical professional living with T2DM and two community stakeholders from the advisory group participated in the consensus technique sessions. Throughout the study, feedback was given to all participants on the results of the techniques developed, and it is hoped that, in the future, people will continue to be involved in the implementation and dissemination phases of the results.

4. Data Analysis

The quantitative data from both techniques were analysed via the score obtained in the vote by the participants, and the mean, standard deviation (SD) and percentage were calculated using the JAMOVi software package 2.3.26 a free and open statistical software designed for analysing descriptive and inferential statistical data. During the voting process in the modified NGT, the poll was anonymous, and each expert did not have access to the vote of another expert participating in the meeting or questionnaire. The expert’s comments and responses were introduced and discussed during the first and second meetings of the modified NGT. The qualitative data were transcribed from the NGT meetings and, in the Delphi Panel, extracted from Google Forms® into an Excel spreadsheet. The data were analysed following the steps of deductive thematic analysis [47, 48]. The analysis was carried out independently by two members of the research team who coded the opinions of each participant according to the themes previously coded in the modified NGT (Role of the diabetes specialist nurse, Role of the social prescriber, Role of the community intervener, Prescription of the HP intervention and Articulation process) and the categories of the modified Delphi panel (cross-cutting components of the intervention, physical activity, nutrition, medication management, self-control and well-being). A third research team member reviewed the coding carried out by the other two research members and conducted the final analysis. Coding the qualitative data made it possible to analyse the experts’ perspectives and incorporate the intervention functions of the Behaviour Change Techniques [11] into the modelling of pre-established interventions or the creation of new ones. In this way, the integrated analysis of quantitative and qualitative methods aimed to ensure that each component was closely aligned with the established objectives and followed the experts’ perspectives. The endorsement or rejection of a statement was defined as a score on a Likert scale above 3.

5. Results

5.1. NGT

All 12 experts participated in both meetings on the modified NGT, achieving 100% attendance (Table 1).

| Nominal group technique experts (characteristics) | n (%) | M (± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 10 (83.3) | — |

| Male | 2 (16.7) | — |

| Age | — | 46.2 (± 6.7) |

| Nurse | 10 (83.3) | |

| Diabetes in primary care | 2 (20.0) | |

| Diabetes in primary care living with T2DM (advisory group member) | 1 (10.0) | |

| Specialised in medical surgery (diabetes) | 3 (30.0) | |

| Specialised in community and public health | 3 (30.0) | |

| Specialised in rehabilitation | 1 (10.0) | |

| Specialised in psychiatry and mental health | 1 (10.0) | |

| Community stakeholder | 2 (16.7) | |

| Community-based service (advisory group member) | 1 (10.0) | |

| Community stakeholder with experience in social prescribing | 1 (10.0) | |

| Job location | ||

| Primary care diabetes consultation | 4 (33.3%) | |

| Primary care | 2 (16.7%) | |

| Community public health unit | 1 (8.3%) | |

| Community care unit | 3 (25%) | |

| Local community | 2 (16.7%) |

- Note: Data are n (%) and M (± SD).

Steps 1 through 5 were addressed during the first meeting, while Step 6 was covered in the second meeting. Table 2 presents the consensus results obtained through online voting in Meeting I and Meeting II, including average scores based on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 9, where one to three indicates low consensus, four to six moderate consensus and seven to nine high consensus, as well as its representation in percentage.

| Agreement rate | ||

|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | % | |

| Meeting I | ||

| Step 1—presentation of the topic under discussion, objectives and voting rules | — | — |

| Step 2—role of diabetes nurse and process of identifying the needs of the person with T2DM | 8 (±0.74) | 88.91 |

| Step 3—prescribing the SP intervention and records in the information system | 8.25 (±0.74) | 91.67 |

| Step 4—social prescriber role and articulation process between diabetes nurse and the social prescriber | 8.42 (±0.67) | 93.53 |

| Step 5—social prescriber role and articulation process between the diabetes nurse and the social prescriber | 8.67 (±0.49) | 96.29 |

| Meeting II | ||

| Step 6—social prescribing model flowchart for the people with T2DM | 8.42 (±0.51) | 93.52 |

- Note: Data are M (±SD) and %.

-

Step 1—Presentation of the topic under discussion, objectives and voting rules.

-

At the beginning of the first meeting, the session organisation, the objectives and the role of each participant were presented. Before the next steps began, the voting method was clarified to the expert group via a Likert scale ranging from 1–3 (very low agreement), 4–6 (low agreement) and 7–9 (agreement).

-

Step 2—Role of the diabetes nurse and process of identifying the needs of the person with T2DM.

-

In the second step, the role of the diabetes nurse in the need identification process was discussed. It is the phase in which the nurse, through the interview, understands the person’s needs and helps them establish the objectives they want to achieve. With the subsequent development of an individualised and person-centred plan and recording of data in the person’s medical records in the computerised health system, this phase received 88.91% agreement among the experts.

-

From this initial reflection, the experts emphasised the importance of including the family or caregiver in the process. They also highlighted the need to assess a person’s economic situation beforehand, as financial limitations may affect their ability to maintain behaviours such as following a balanced and adequate diet. Additionally, exploring a person’s health beliefs and behaviours is crucial for understanding their knowledge about the illness and their ability to manage and control future complications.

-

Step 3—Prescribe and record the SP intervention in the information system.

-

At this stage, discussions focussed on how diabetes nurses can propose community activities tailored to individual needs, aimed at improving the control and management of T2DM, with the support of a purpose-designed algorithm (supporting file 1). Furthermore, the group debated the necessary documentation of these interventions in the health primary care information system. A consensus of 91.67% was achieved on these points. The experts highlighted the importance of allowing the person time to reflect and choose activities that align with their personal goals and needs between the nursing interview and the appointment with the social prescriber. They also stressed the need to formalise the individual’s commitment to the intervention, ensuring accountability and promoting adherence to the process.

-

Step 4—Social prescriber role and articulation process between diabetes nurses and social prescribers.

-

The fourth phase explored the social prescriber role and the referral process with diabetes nurses. Each person is presented with the different activities that may arise as a response to the identified problems. In this study, the role of the social prescriber was taken on by a diabetes nurse and research team member. The follow-up carried out by the social prescriber and the number and frequency of contacts with the person with T2DM were also discussed. A 93.53% consensus was reached. The experts also discussed the event of withdrawal or difficulties; the social prescriber should inform the diabetes nurse, and the person should continue to be followed up in the context of regular appointments.

-

Step 5—The social prescriber and the voluntary and community stakeholders reference person liaison.

-

At this point in the process, the voluntary and community stakeholders were debated, and the liaising process with the social prescriber was discussed, with 96.29% agreement. It has been proposed that in the event of nonadaptation to the activity to be carried out in the community, the community stakeholder should inform the social prescriber of the difficulties encountered by the person with T2DM. Subsequently, the social prescriber should work with the person to validate these difficulties, adjust or redefine their path, and provide feedback to the community stakeholder on the person’s decision.

-

Step 6—SP model flowchart for people with T2DM

-

During the second meeting, the final flowchart of the SP model for T2DM (see supporting file 2) was presented. The flowchart outlined the interactions between key participants in the intervention, including the person with T2DM, the diabetes nurse, the social prescriber and the voluntary and community stakeholders. This model provided a clear visualisation of all articulation points, facilitating the consolidation of previously discussed topics. Ultimately, the final model achieved 93.52% consensus among the experts.

6. Delphi Panel

The first phase comprised quantitative data analysis and the second phase qualitative analysis of the comments corresponding to each item. Individually, every comment was analysed and considered for integration or modelling of the items listed under study and subject to expert evaluation in the next round. After round one and the comment analysis, before round two, some points were clarified with the experts through feedback on the results of the first round.

6.1. First Round

In the first round, all 10 panellists (100% of the sample) (Table 3) voted on 27 interventions, which were divided into six categories: Category 1, cross-cutting components of the intervention; Category 2, nutrition; Category 3, physical activity; Category 4, medication management; Category 5, self-monitoring; and Category 6, well-being (Table 4).

| Delphi panel experts (characteristics) | n | M (±SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 8 (80.0) | — |

| Male | 2 (20.0) | — |

| Age | 50.2 (± 9.7) | |

| Nurse | 2 (20.0) | — |

| Specialised in Medical-Surgery (Diabetes) | 1 (10.0) | — |

| Specialised in rehabilitation (diabetes in primary care) living with T2DM | 1 (10.0) | — |

| T2DM person | 2 (20.0) | — |

| Social prescribing expert | 2 (20.0) | — |

| Community stakeholder (community-based service and advisory group member) | 1 (10.0) | — |

| Nutrition professional | 1 (10.0) | — |

| Physical professional | 1 (10.0) | — |

| Social worker (living with T2DM) | 1 (10.0) | — |

- Note: Data are n (%) and M (± SD).

| First round | % Per question | Second round | % Per question (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category 1: cross-cutting components of the intervention (T) | 91.6 | |||

| T1—… the participant is informed by the Diabetes Nursing about the different activities of physical exercise, nutrition, management of the medication regime, safety (self-monitoring), well-being and health literacy in the community | 90 | |||

| T2—… the participant is provided with the ‘Diabetes Social Prescribing Passport’ which explains the recommendations for basic care in T2DM and the different resources in the community that offer an integrated response | 90 | |||

| T3—… the participant is informed that they will be accompanied by a social prescriber and will have face-to-face and telephone contacts: 4 x telephone contacts (1st, 2nd, 6th and 10th week) 2 X face-to-face contacts (4th and 8th week) | 92.5 | |||

| T4—… the social prescriber evaluates the participant′s progress in the face-to-face and telephone sessions according to the personalised plan defined in the different areas of fundamental care in DMT2 (records in the health system) | 95.5 | |||

| T5—… the participant is encouraged to record in the ‘Diabetes Social Prescribing Passport’ their difficulties/barriers or facilitators in complying with the agreed plan in the different areas of fundamental T2DM care throughout the program | 92.5 | |||

| T6—… the participant is informed that they will receive messages (SMS) encouraging and reminding them about the different essentials of T2DM care (2 x weeks) | 72.5 | T6—… the participant is informed that they will receive messages (SMS) encouraging and reminding them about the different essentials of T2DM care (1 x weeks). | 92.5 | |

| T7—… the participant is encouraged at the Diabetes Nursing Appointment to evaluate their objectives, and the goals achieved through their participation in the program (records in the computerised health system): … 12th week (90d) | 90 | |||

| T8—… the participant is encouraged to use their Social Prescription Kit (consisting of a rucksack, pedometer, water bottle, and ‘T2DM Social Prescribing Passport’) | 90.6 | |||

| T9—… the participant is informed that they should bring their ‘DMT2 Social Prescribing Passport’, which contains their individual SP program, with timetables and activities, for validation with community partners | 90.6 | |||

| Category 2: physical activity (P) | 88.5 | |||

| P1—the participant is encouraged to do different physical activities in the community, in groups (e.g., yoga, pilates, zumba and gymnastics) or individually, to carry out 150 min/week of moderate physical activity and/or 75 min/week of intense physical activity (minimum) (WHO, 2020) | 90 | |||

| P2—… the participant is encouraged to record their physical activity in their ‘Social Prescribing Passport’ | 90 | |||

| P3—… the participant is encouraged to do gymnastics, dance, and participate in the folkloric ranch (moderate physical activity) 120 min/week (WHO, 2020) | 85 | |||

| P4—… the participant is encouraged to take part in theatre classes (multicomponent intensity activity (strength and balance) … 2 x weeks (WHO, 2020) | 85 | |||

| P5—… the participant is encouraged to carry out moderate/intense physical activity individually on walking trails in the city three times a week/50 min | 85 | |||

| P6—… the participant is encouraged to carry out moderate physical activity (walking) in a Diabetes support group (APDP—Associação Protectora dos Diabéticos de Portugal): … 1 x a month/120min | 77.5 | P6—… the participant is encouraged to do moderate physical activity in walking groups: … 2 x a month | 90.6 | |

| P7—… the participant is encouraged to take 7,000 steps a day, using a step counter (pedometer and mobile application): daily | 82.5 | P7—… the participant is encouraged to take 7,000 steps a day, using a step counter (pedometer, mobile application) with a daily record in the Social Prescribing Passport | 93.8 | |

| Category 3: nutrition (N) | 87.6 | |||

| N1—… the participant is encouraged to record their diet (e.g., eating mistakes) in their ‘Social Prescribing Passport’ | 85 | N1—… the participant is encouraged to record their diet (e.g., difficulties, strategies, goals) in their ‘T2DM Social Prescribing Passport’ | 90.6 | |

| N2—… the participant is encouraged to attend the ‘healthy snacks’ workshop: … 1x in the program, lasting 60 min | 85 | |||

| N3—… the participant is encouraged to attend a group session on ‘Uncomplicating Diabetes… what is the responsibility of my diet in my disease’: … 1x in the program, lasting 60 minutes | 85 | |||

| N4—… the participant is encouraged to attend a group session on ‘What labels tell us—let′s investigate’: … 1x in the program, lasting 60 min | 90.5 | |||

| N5—… the participant is encouraged to take part in a visit to the municipal market… ‘Let′s get to know different options and make healthy choices’: … 1x in the program, lasting 50 min | 92 | |||

| Category 4: medication management (M) | 88.15 | |||

| M1—… the participant is encouraged to attend Health Literacy classes on the medication regime 1 x program, lasting 50 min | 82.5 | |||

| M2—… the participant is encouraged to attend a group session on ‘Uncomplicating Diabetes… what is the responsibility of my medication in my illness’: … 1x in the program, lasting 60 minutes | 93.8 | |||

| Category 5: self-monitoring (S) | 90.5 | |||

| S1—… the participant is encouraged to session on ‘Let′s look down … at my feet’: … 1 x program | 92 | |||

| S2—… the participant is encouraged to attend Health Literacy classes on self-monitoring in diabetes: … 1 x program, lasting 50 min | 82.5 | |||

| S3—… the participant is encouraged to attend a group session on ‘Uncomplicating Diabetes… what is it? What are its complications’: … once in the program, lasting 60 minutes | 93.8 | |||

| S4—… the participant is encouraged to attend a group session on ‘Uncomplicating Diabetes… how to interpret low and high values? What to do? 1x in the program, lasting 60 minutes | 93.8 | |||

| Category 6: well-being (W) | 87.1 | |||

| W1—… the participant is encouraged to take part in activities for relaxation and physical, psychological, and mental well-being (yoga, meditation): … 1 x a week | 85 | W1—… the participant is encouraged to take part in activities for relaxation and physical, psychological, and mental well-being (yoga, meditation): 2 x weeks | 90.6 | |

| W2—… the participant is encouraged to attend a volunteer activity in the city: … 1 x a week | 80 | |||

| W3—… the participant is encouraged to attend the religious choir group. … 1 x a week | 42.5 | W3 was excluded in Round 2 | ||

| W4—… the participant is encouraged to attend a cultural activity ‘Getting to know the city where I live’—Amadora Museum, lasting 50 min | 77.6 | W4—… … the participant is encouraged to attend a cultural activity (exhibition and museum visit), lasting 50 min | 90.6 | |

- Note: Data are %.

6.1.1. Category 1—Cross-Cutting Components of the Intervention

T6-‘… the participants were informed that they would receive messages (SMS) of encouragement and reminding them about the different essentials of T2DM care (2 x weeks)’

According to the experts’ comments, the frequency of the intervention was high, so the intervention was shaped by integrating the perspective presented. After modelling, the data were submitted again for analysis by the expert panel in the second round. For the expert’s commentary, two new interventions (T8 and T9) were proposed and voted on in the second round.

6.1.2. Category 2—Physical Activity

In the second category, interventions dedicated to physical activity were analysed. In this category, almost all the statements scored ≥ 80%. In intervention P6 which obtained 77.5% agreement.

6.1.3. Category 3—Nutrition

N1—‘… the participants were encouraged to record their diet (e.g., eating mistakes) in their T2DM SP Passport’.

6.1.4. Category 4—Medication Management

M2—‘… the participant is encouraged to attend a group session on ‘Uncomplicating Diabetes… what is the responsibility of my medication in my illness: 1x in the intervention, lasting 60 minutes’.

6.1.5. Category 5—Self-Monitoring

S3 intervention—‘… the participant is encouraged to attend a group session on ‘Uncomplicating Diabetes… what is it? What are its complications’’: … once in the intervention, lasting 60 minutes’

and

S4—‘… the participant is encouraged to attend a group session on ‘Uncomplicating Diabetes… how to interpret low and high values? What to do? in the intervention, which lasted 60 minutes’

6.1.6. Category 6—Well-Being

W1—‘… the participant is encouraged to participate in activities for relaxation and physical, psychological, and mental well-being (e.g. yoga, meditation) 1 x week’

W3—‘… the participant is encouraged to attend the religious choir group. … 1× a week’, In the last intervention of this category, intervention W4 obtained 77.6%.

W4—‘… the participant is encouraged to attend a cultural activity ‘Getting to know the city where I live’—Amadora Museum, lasting 50 min’,

Established on the experts’ suggestions, the data were refined and analysed in the second round.

6.2. Second Round

During the second round online, 8 panels of experts took part (80% of the sample). One nurse specialising in Medicine-Surgery (Diabetes) and one SP expert did not take part. After six interventions were modelled, one was removed, and five new interventions were incorporated, the second round took place, where 11 interventions were analysed. The second round produced a final list of 30 interventions, encompassing the six complex SP intervention categories.

6.2.1. Category 1—Cross-Cutting Components of the Intervention

T6—‘… the participants were informed that they would receive messages (SMS) of encouragement and reminding them about the different essentials of T2DM care (1 x week)’

The two new interventions resulting from the expert’s feedback, T8 and T9, achieved a consensus of 90.6%.

6.2.2. Category 2—Physical Activity

P6—‘… the participant is encouraged to do moderate physical activity in walking groups 2 x a month’

P7—‘… the participant is encouraged to take 7000 steps a day, using a step counter (pedometer, mobile application) daily with a daily record in the SP Passport’

6.2.3. Category 3—Nutrition

N1—‘… the participants were encouraged to record their diet (e.g., difficulties, strategies, goals) in their T2DM SP Passport’.

6.2.4. Category 4—Medication Management

For most people with T2DM, medication self-management is part of their day-to-day self-care through taking oral therapy or administering injectable treatment and some patients revealed have difficulty completing the prescribed medications according to the instructions [49]. Established on the experts′ comments, the new intervention M2 was built on the importance of the person’s knowledge of their responsibility for taking their medication and obtained a 93.8% consensus.

6.2.5. Category 5—Self-Monitoring

The experts stressed the importance of understanding target glucose ranges and recognising abnormal blood sugar levels as key to effective diabetes management. They highlighted that a patient’s knowledge and ability to respond to off-target glucose levels can help slow disease progression and prevent complications. Based on these insights, the research team introduced two new interventions, S3 and S4, which reached an 87.5% consensus.

6.2.6. Category 6—Well-Being

W1—‘… the participant is encouraged to participate in activities for relaxation and physical, psychological, and mental well-being (e.g., yoga, meditation) 2 x week’

W4—‘… the participant is encouraged to attend a cultural activity ‘exhibition, museum visit’—, lasting 50 min’,

7. Discussion

Consensus techniques, such as the NGT and the Delphi panel, are important in comprehensive design and effective health programs, as they bring together different perspectives and generate agreement on complex issues [29, 30]. This study thus aims to synthesise the results of expert consensus by integrating the two consensus techniques, which allowed for a deeper understanding and greater refinement of the SP intervention model and its multicomponents. The decision to use both methods was based on the essential qualities that each offers which facilitate an in-depth exploration and analysis of the main points of discussion under study. Through their knowledge and experience, the participants contributed significantly to reaching a group consensus coproducing an SP intervention to promote self-care behaviours, empowerment and autonomy, commitment to health goals and informed decision-making. A person-centred SP model development is essential to ensure that health interventions align with what matters to people. At the same time, it proposes to improve health literacy, encouraging each patient to take a more active role in promoting their health and well-being. Improving health literacy through the intervention of SPs can help them better understand their condition, adopt healthy practices and use health services more efficiently. Through networking with voluntary and community sectors, the model allows participants to adapt and build a path to a healthier and more balanced life, aligned with their values and needs. It also provides time for the person to reflect, ask questions and be actively involved in their health journey. Living with a chronic and complex disease such as T2DM requires an approach aimed at improving the person’s involvement in their daily self-management. We are aware of the burden of T2DM and the different self-care behaviours that are required. Due to its complexity, this SP intervention has several multicomponents that make it up, which can lead to overburdening. However, we would like to emphasise that each person will define their objectives in a personalised and independent way, deciding which areas they wish to improve.

A clear structure with defined roles for primary care professionals, social prescribers and community partners improves the cohesion and effectiveness of the intervention. This SP approach ensures that people’s needs are accurately identified and addressed, with input from different health and community stakeholders [41]. Previous research suggests that limiting the number of clinical and nonclinical professionals involved in the SP intervention can avoid role confusion [50]. Thus, resulting from the consensus this model adopts an optimised and simplified process flow structure with clearly defined responsibilities aligned with the objectives of each participant. Using a flowchart for the model facilitates the understanding of the steps of a process, their sequence, responsible parties, scope (start and end points) and decision points with their possible outcomes [51]. Due to its simple and organized presentation, it can be thought about the transferability to different areas or in areas inside diabetes mellitus. In this model, the nurse plays the role of social prescriber by referring patients to community resources, assessing health needs and addressing the psychosocial factors that influence self-care and diabetes management. As in other countries, nurses have been chosen as social prescribers because of their proximity, ability to identify individual needs and ease of setting goals with the person [52]. Nurses are key to connecting patients with community activities, reinforcing the success of the intervention by aligning behaviour change plans with the motivations of each patient [53]. This model allows for integration into the national public health system, enabling it to be used by primary healthcare professionals and recorded in the patient’s medical record, allowing for greater reliability and evaluation of results, supporting the development and impact of the intervention. As an evolution of a deeper understanding of the model, participants gained a deeper comprehension of each stage of the process, allowing for continuous evaluation and refinement. Ultimately, this iterative approach led to a consensus among the experts, achieving an agreement rate of 93.52%.

Furthermore, this study reached a consensus on a set of multicomponent interventions that address multiple needs of T2DM patients and domains of self-care behaviours, providing a holistic and customisable intervention. Composed of six categories covering different areas such as physical activity, nutrition, medication management, self-monitoring and well-being, the expert panel mostly received the interventions with a consensus rate of 88.9%. Participants noticed the relevance of integrating different areas the person can develop according to their preferences and specific needs. Except for one intervention related to religion in the last category, this intervention was mostly rejected by the person with T2DM and some of the professionals involved. The research team therefore opted to remove it. However, the literature shows that religion and spirituality can play important roles in coping with the disease process and influencing self-care behaviours in the person with T2DM [54, 55]. It is sometimes reported that professionals find it difficult to approach religious activities and consider that they do not respond to the person’s needs in managing T2DM [55].

A preliminary mapping of voluntary and community sector resources was important, as it helped to understand the offers made by these resources, to establish channels of communication between contexts and to co-design the intervention. Each domain of the multicomponent SP intervention was aligned to support the specific self-care behaviours of this model, supported using behaviour change techniques [11], which included strategies such as encouragement, support, motivation and resources to support the interventions developed. The use of resources is considered important in involving the person in the decision-making process, improving health behaviours and self-care management [44]. The information provided through resources should involve verbal, written or digital forms [44]. Among the cross-cutting components, the first category, different approaches have been combined, such as SMS messages, face-to-face and telephone follow-up, as well as resources such as pedometers and screening booklets. Each plays an essential role: face-to-face follow-up strengthens the bond between health professionals and patients and allows for more detailed assessments, while telephone follow-up keeps the person connected and offers ongoing support [56]. During the first round, the expert panel suggested the creation of an SP kit in T2DM, which would bring together the resources made available for the development of the interactive components. After analysing the perspectives presented, a kit consisting of a backpack, SP passport, pedometer and water container was included as a new intervention to be carried out and explained by the diabetes nurse during the counselling and referral process. Together, these approaches form an integrated SP intervention to empower people in self-care, promote health literacy and improve the quality of life and well-being of the person with T2DM. A final set of 30 SP interventions established the multiple complex components of the SP intervention in T2DM. The design for and with the person living with T2DM integrates a wide range of community resources and activities, promoting self-care, health literacy and physical, emotional and social well-being.

8. Strengths and Limitations

The expert group of clinical and nonclinical professionals, community stakeholders and the person who lives with T2DM collaborated in a cocreation process to refine the assessment of how specific SP interventions could impact the health behaviours of the person with T2DM. Their feedback, which drew from their expertise in areas such as diabetes, SP, nutrition, physical activity and social environments, played a crucial role in shaping the model and the components of the SP intervention future. The active involvement of T2DM patients, as future users of the intervention, was vital for conceptualising solutions that meet their specific needs and are feasible in terms of location, frequency and duration of use. Involving stakeholders from various backgrounds guarantees a more holistic perspective, addressing a wide range of needs and concerns that a more homogeneous group might otherwise be overlooked. As a key strength, a participatory approach increases the likelihood of the SP intervention acceptance and engagement, fostering trust between patients, healthcare providers and intervention developers.

One of the study’s limitations lies in the facilitating role of the modified NGT process. The facilitator, as a research team member, may inadvertently influence how the content is presented and discussed in group settings. This close relationship between the facilitator and the subject matter could introduce bias, steering discussions in a way that might foster specific ideas or perspectives, thus compromising the neutrality of the facilitation. This influence could impact group dynamics, potentially skewing the outcomes and undermining the objectivity of the results. Another limitation may stem from the small number of participants in the Delphi panel. The literature presents varying definitions regarding the ideal number of participants, with the adopted number being described as valid [53]. Although all relevant parties were represented on the panel, the number of participants, especially the number of T2DM patients included, could be improved in future research. However, the consensus achieved through the combination of both techniques involved a group of 22 experts, enhancing the robustness of the data obtained.

9. Conclusion

In managing chronic diseases such as T2DM, SP plays an essential role by providing support beyond traditional approaches, promoting lifestyle changes and encouraging self-care behaviours. A person-centred approach creates the opportunity to use community resources tailored to individual needs, empowering them to take an active role in their health and well-being. By building a consensus among various experts, it was possible to outline a solid and structured model and intervention components to support and respond to the specific self-care and management needs of the T2DM patient. The different perspectives, whether from health professionals, patients or community stakeholders, were important pillars in identifying gaps, building new interventions and consolidating the proposed interventions. The active inclusion of the person and the involvement of the community from the earliest stages of development is fundamental to guaranteeing the adaptability of interventions to local realities. Adopting these approaches increases suitability and adherence to future interventions, ensuring that SP interventions meet the diverse needs of the person and their community.

Nomenclature

-

- BCW

-

- Behaviour change wheel

-

- NGT

-

- Nominal group technique

-

- SP

-

- Social prescribing

-

- T2DM

-

- Type 2 diabetes mellitus

-

- WHO

-

- World Health Organization

Ethics Statement

The development of this study is part of a research study on self-care and health literacy among persons with T2DM, approved by the ARSLVT Health Ethics Committee under registration number 5078/CES/2022. In both consensus techniques, ethical principles were respected, and all invited participants took part based on their informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research does not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

This study is part of a larger project based at the University of Lisbon on Community health promotion through nursing intervention in Social Prescribing. The Lisbon Centre for Research, Innovation, and Development in Nursing (CIDNUR), ESEL’s research unit, supports the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants in this study for their support and collaboration.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

All the data that resulted from the consensus techniques are included within the body of this published article.