Centering Humanizing, Individualized Care Amid Systemic Barriers: A Qualitative Exploration of Provider Approaches to Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Unhoused Adults

Abstract

Palliative and end-of-life (PEOL) care offers many benefits to those with life-limiting illness; however, people experiencing homelessness face systemic and social barriers to accessing such care. Healthcare (HC) and social service (SS) providers who work with unhoused individuals have essential roles and insight for how PEOL needs are addressed among this population which may inform opportunities to improve care. This study, therefore, explores Colorado-based HC and SS providers’ approaches working with unhoused individuals with PEOL needs. An exploratory–descriptive qualitative approach was used to conduct semistructured interviews with HC and SS providers in Colorado who provided direct care or services to adults. An iterative thematic analysis approach was used to code and analyze interviews. Seventeen providers were interviewed between June and September 2022, representing settings including hospitalist specialty services, hospice, housing/homeless services, aging services, and community mental health. Amid systemic challenges, including lack of resources and pervasive stigma toward unhoused individuals, providers highlighted person-centered and holistic approaches to care that prioritize building trust and honoring dignity and autonomy. Providers emphasized the importance of organizational commitment to these humanizing approaches while transforming culture surrounding poverty and end-of-life. Further, interviews identified potential solutions to improve PEOL care for individuals experiencing homelessness, including specialized interventions (e.g., mobile palliative care). These findings highlight realistic, humanizing approaches to care providers can incorporate into everyday practice and support the need for specialized PEOL services, policy reform in housing and HC (better housing solutions, hospice reimbursement, etc.), and efforts to address and disrupt homelessness stigma.

1. Introduction

According to the National Academy of Medicine, access to palliative and end-of-life (PEOL) care, including hospice, is essential for alleviating pain and suffering while providing quality care to people with life-limiting or terminal illness [1]. Life-limiting illness refers to an advanced, chronic illness that limits someone’s life expectancy, such as cancer, heart failure, or chronic kidney disease [2], while terminal illness is the end stage of life-limiting illness marked by irreversible decline and likelihood of death within a matter of months [3]. Individuals who receive PEOL care often show reduced pain and symptom intensity and less existential distress and even live longer than terminally ill individuals who do not receive palliative-focused care [4]. PEOL services can also reduce healthcare (HC) expenditures by minimizing the need for emergency department (ED), hospital, and intensive care services and associated costs [5].

Despite these benefits, inequities in PEOL services persist. In fact, the basic assumptions that drive PEOL practices—having an informal support network to provide care, having a stable, secure living arrangement, and financial resources to afford room and board costs in long-term care facilities or additional in-home care—exacerbate these inequities [6, 7]. People experiencing homelessness in particular face many barriers to receiving PEOL care, an issue which has become a focus of research and advocacy across international contexts [6, 8–12].

The United States is facing a worsening affordable housing crisis and an increase in the number of unhoused individuals, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, rising inflation, and growing economic inequalities [13–15]. In 2024, 771,480 people were recorded as experiencing homelessness in the United States—the highest number ever recorded in the country and an 18% increase from the previous year [13]. According to the state of Colorado’s Point-in-Time Count, approximately 14,439 people were experiencing homelessness in 2023, demonstrating a 39% increase in the state from 2022. Over 30,000 people accessed homelessness services in the city of Denver alone [16].

People experiencing homelessness face higher rates of chronic and life-limiting illness and higher disease burden than stably housed populations [17, 18]. They die at younger ages than stably housed individuals, are less likely to receive comprehensive care, and are more likely to die in unsupportive settings, including on the streets [12, 19–21]. Unhoused individuals have high rates of acute HC utilization, including ED visits and hospital admissions [22]. And although the average life expectancy of someone experiencing chronic homelessness is 50 years, the aging unhoused population is growing, with one-third of unhoused adults aged 50 years or older [23–25].

A number of studies have identified barriers to accessing PEOL services among unhoused individuals across individual-, provider-, and structural-level factors [21, 26, 27]. The daily challenges of homelessness present competing priorities for survival (i.e., finding food/shelter), often placing long-term disease management below what may be perceived as more urgent needs [12]. Further, many unhoused individuals report having fractured relationships with families and overall poor social support [21]. At the provider level, gaps in knowledge of PEOL care or homelessness as well as challenges in treating life-limiting illness with cooccurring substance use or mental illness often present barriers in addressing PEOL needs for unhoused individuals [26, 28, 29]. Further, stigmatized attitudes toward homelessness among providers, particularly within HC organizations, may impact care decisions and create distrust among unhoused individuals requiring care [12, 30, 31]. In fact, negative perceptions of HC providers and fear of poor care from a history of mistreatment and discrimination have been emphasized as critical factors influencing unhoused individuals avoiding PEOL care across multiple studies [21, 27, 32].

At the structural level, many organizations are unprepared to address the complex needs of unhoused individuals and as a result often fail to provide holistic, individually appropriate plans of care [12]. In fact, there are few specialized services to address the needs of people experiencing homelessness with life-limiting or terminal illness [33]. Program restrictions or policies around substance use limit the eligibility of unhoused individuals who use substances to receive care [34, 35]. Further, multiorganizational collaboration and coordination often required to appropriately address complex care needs is rarely achieved and difficult due to fragmented HC and social services (SSs) [27]. Ultimately, public perceptions of poverty and homelessness influence not only the quality of care but also policies that impact the health of unhoused individuals and the availability of services [18, 36].

HC and SS providers are essential facilitators in access to care or services for unhoused individuals, often serving as advocates for ensuring unhoused individuals are referred to appropriate services or levels of care and helping them navigate complex systems [37]. Conversely, as illustrated in provider-level barriers to PEOL care above, they can also potentially hinder care. Given their critical roles, this study focuses on access to PEOL care among unhoused individuals from the provider perspective. While previous studies have examined PEOL issues from the perspectives of unhoused individuals, PEOL clinicians, and homeless service providers [27, 38], few have included perspectives of providers working outside PEOL or homelessness services. Further, a deeper understanding of provider approaches to care in the context of Colorado’s social and political environment may yield valuable information to direct solutions toward improving PEOL care for this population within the state. The purpose of this qualitative study is, therefore, to explore the perspectives and approaches of HC and SS providers on access to PEOL for individuals experiencing homelessness in Colorado. The following research questions guided the study: (1) How do HC and SS providers describe their approach working with adults experiencing homelessness with life-limiting illness? and (2) how do HC and SS providers describe potential resources or solutions that may better support PEOL needs for adults experiencing homelessness?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Theoretical Framework

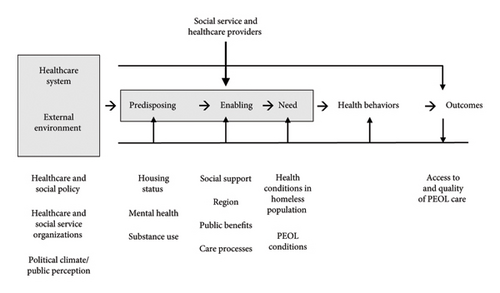

Using an exploratory–descriptive qualitative approach [39], individual semistructured interviews were conducted between June and September 2022 with 17 SS and HC providers. The study design and data collection were guided by the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations (BMVPs) to explore the provider role as an enabling factor within the context of other influences of PEOL service use and outcomes for unhoused individuals. The BMVP expands on Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use to include “vulnerable domains” of predisposing (individual characteristics), enabling (which impact the ability to obtain care), and need factors (health conditions and comorbidities) that commonly characterize certain marginalized group experiences, including those experiencing homelessness [40, 41]. Within this model, providers are considered enabling factors alongside other mechanisms within health and SSs, including organizational financing, care processes, volume of patients/clients, and provider-to-population ratio [41, 42]. To account for systemic factors that may influence providers’ approaches to care, the current study adapted the BMVP framework to include environmental factors (e.g., HC and social policy), which were included in an update of Andersen’s original model [42] (Figure 1). The current study focuses on enabling factors (providers and the organizations they work within) and external environment (systems) within the context of access to PEOL care for unhoused individuals.

2.2. Sampling and Recruitment

Colorado-based HC and SS providers whose roles included direct care or services to adults over age 18 were included in the study’s sample. Eligibility criteria were intentionally broad to allow individuals to participate from diverse professions and settings that interact with unhoused adults with life-limiting illness. For this study, HC providers included individuals working within HC settings who provide direct care to patients (nurses, physicians, social workers, etc.). SS providers included those working in the SS sector (aging services, housing/homelessness services, etc.) who provide direct services to clients.

A combination of purposive, convenience, and snowball sampling was used to recruit prospective participants. Most participants were recruited from a previous online survey of Colorado-based HC and SS providers. After survey completion, respondents could indicate interest in future interview participation and provide contact information. Prospective interviewees from the survey were contacted for study participation if they indicated experience working with unhoused patients or clients in their role. Additional participants were identified through snowball sampling or direct outreach via professional networks with the goal of including individuals from a diverse array of SC and HC settings who could share perspectives on working with unhoused adults.

A total of 22 individuals were contacted for participation through survey respondent volunteers (17) and direct outreach via snowball sampling or professional networks (5); 20 of whom agreed to schedule an interview. Of those 20 individuals, three did not complete interviews: Two canceled their interview times due to scheduling conflicts, and one did not make their interview and could not be reached again upon follow-up. Ultimately, a total of 17 participated in the study, and the authors stopped recruitment once no new insights were emerging from the interviews.

2.3. Data Collection

Interviews were conducted virtually via Zoom software by the first author, who was a doctoral candidate at the time of data collection and is a white, cisgender woman with a background in HC and social work research and over 7 years of experience conducting qualitative interviews. Interviews lasted an average of one hour (ranging from 30 to 90 min). A semistructured interview guide, informed by the literature and input from providers with expertise in PEOL and/or homelessness, was used to inquire about participants’ organizational setting, their experiences and approaches in working with unhoused individuals with life-limiting illness and PEOL needs, facilitators and barriers to addressing PEOL needs, and resources required to improve access to care. Interviews were audio-recorded with participant permission and transcribed using Rev Artificial Intelligence (AI) software. Following transcription, transcripts were reviewed and cleaned for accuracy before being uploaded to Atlas.ti qualitative software for storage and coding. Participants also filled out a questionnaire that included sociodemographic items (gender, race, and age) and questions about their current position, organizational setting, and number of years working in their profession.

2.4. Ethics Considerations

The study was approved by the University of Denver Institutional Review Board (approval no. 1879181). Participants were provided with a document outlining study participation and consent information prior to the scheduled interview. Additionally, all participants engaged in a virtual, face-to-face informed consent process with the first author and provided verbal consent twice prior to the start of the interview (once prior to the recording and again at the beginning of the recording). Participants received a $25 gift card for their time.

2.5. Analysis

Thematic analysis was used to analyze the data using six phases: (1) familiarizing with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report [43]. Three authors (M. Pilar Ingle, Elise K. Matatall, and Asia Cutforth) participated in both the coding and analysis process to improve coding consistency and reduce bias.

Coding was conducted in two stages using a mixed inductive–deductive approach. The first stage included an inductive process, where coders separately open-coded four interviews. One interview was read separately by each coder and reread to generate an initial list of codes. The next interviews were reviewed only after open codes were discussed and agreed upon for each preceding interview. In the second stage, an initial codebook was developed—informed by the interview guide and organized into categories according to factors in the BVMP framework—based on open codes developed in the first stage. All interviews were then coded by the first author and split between two second coders. Each coding dyad met to discuss coding decisions. All three coders met periodically to resolve coding differences and discuss any changes to the codebook as needed.

Following coding completion, codes were sorted into potential themes using tables in Microsoft Office Word. Candidate themes and subthemes were selected, reviewed, and refined by reading through related interview excerpts. Then, candidate themes were reviewed in relation to the entire dataset through visual mapping using Freeform, a digital whiteboarding software [43]. Final themes and subthemes were selected, defined, and reviewed by all authors.

2.6. Analytic Rigor and Trustworthiness

The authors exercised ongoing reflexivity throughout the study via memoing, peer debriefing, and mentor supervision to promote awareness of researcher bias, values, and experiences that had the potential to impact the interview process and interpretation of the findings [44]. For example, the analysis team began a discussion of each interview with the question “What came up for you as you read this transcript?” We would discuss any notable reactions identified by each coding team member and explore how that may have impacted coding or interpretation. Several strategies were incorporated to address qualitative rigor and trustworthiness, including the use of triangulation, audit trails, and team debriefing. Member checking was also used both during and after the interviews. Throughout the interviews, the first author would often repeat statements back to participants or ask for clarification to ensure understanding of their meaning. Further, a table of initial themes, including definitions and summaries of each theme, was shared with each participant in February 2023 with an invitation to respond with feedback. Four participants responded, each with a positive reception of the themes. No changes were made to the findings based on member checking.

2.7. Statement of Positionality

The authors approach this work from a health equity- and systems-oriented lens, operating from the assumption that health inequities in PEOL contexts for unhoused individuals are preventable and unfair [45]. All with training in social work, the authors represent a variety of professional backgrounds including research in gerontology, social work, and public health, and clinical practice in HC (palliative care, oncology, and inpatient adult/geriatric psychiatry), transitional housing, and mental health. None of the authors have personal experiences of homelessness, and one author has several family members who have experienced housing instability and homelessness.

3. Findings

Seventeen HC (n = 10) and SS (n = 7) providers participated in interviews (Table 1). With a mean age of 42, most participants identified as women and white and reported working in their profession for at least 4 years. The interviews represented a variety of HC and SS settings, outlined in Table 1.

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Woman | 11 | 65 |

| Gender queer | 1 | 6 |

| Man | 5 | 29 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander | 1 | 6 |

| White | 16 | 94 |

| Setting | ||

| Healthcare | 10 | 59 |

| Hospice or palliative care | 5 | 29 |

| Family medicine | 1 | 6 |

| Hospitalist or specialty service | 3 | 18 |

| Recuperative/respite service | 1 | 6 |

| Social services | 7 | 41 |

| Housing/homeless services | 4 | 23 |

| Aging services | 1 | 6 |

| Community mental health | 1 | 6 |

| Nonhospice end-of-life services | 1 | 6 |

| Role | ||

| Case manager | 3 | 18 |

| Director | 4 | 23 |

| Death doula | 1 | 6 |

| Graduate social work intern | 1 | 6 |

| Nurse | 1 | 6 |

| Nurse practitioner | 2 | 12 |

| Physician | 1 | 6 |

| Social worker | 4 | 23 |

| Years in profession | ||

| Less than 1 year | 1 | 6 |

| 1–3 years | 4 | 23 |

| 4–6 years | 5 | 30 |

| 10+ years | 7 | 41 |

| Years in current role | ||

| Less than 1 year | 3 | 18 |

| 1–3 years | 7 | 41 |

| 4–6 years | 3 | 17 |

| 7–9 years | 2 | 12 |

| 10+ years | 2 | 12 |

| Colorado Region | ||

| Southwest | 1 | 6 |

| Denver metropolitan | 11 | 65 |

| Northern Colorado | 4 | 23 |

| Central Colorado | 1 | 6 |

- Note: N = 17. Participants were on average 42 years old (SD = 11.37).

Parallel to previous literature [21], the interviews described systemic and social barriers to PEOL care for unhoused individuals, with one participant stating, “we’re dealing with an inhumane lack of resources.” In addition to this lack of resources, participants described issues surrounding siloed SS and HC systems preventing better continuity of care and interagency collaboration, emotional and workplace strain on providers, and encountering stigmatized attitudes within their organizations and among colleagues toward unhoused patients or clients.

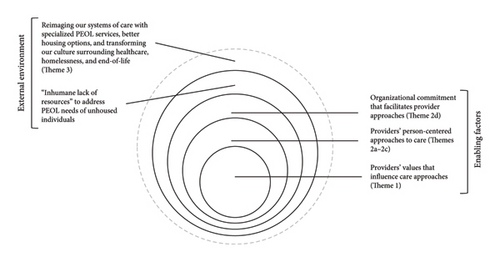

Amid these systemic challenges, participants described approaches to addressing the PEOL needs of their unhoused patients or clients. Three overall themes were identified illustrating provider approaches to care and their suggested solutions to improving PEOL services for unhoused individuals. We first describe the providers’ overarching values that enable and guide their care approaches with unhoused individuals (Theme 1), followed by the providers’ enabling approaches to care in practice (Theme 2). Finally, we describe providers’ suggested solutions which reimagine our health care system and external environment that could improve PEOL care for people experiencing homelessness (Theme 3). Figure 2 illustrates our themes in relation to one another and as they pertain to the external environment and enabling factors within the BMVP.

3.1. Theme 1: “These Are Human Beings That Deserve Basic Care”

Across interviews, providers emphasized the urgent need for improved care for unhoused individuals with life-limiting illnesses, grounded in the humanity and individuality of these clients. While talking about the need to improve care for this population, a program manager for an outpatient hospital service stated, simply, “These are human beings that deserve basic care.”

Oftentimes these are folks who haven′t felt valued, who haven′t felt respected by a medical system, who haven′t felt respected in society… We can come in and show them that we still value them as people. (Physician, palliative care)

It′s this narrative that giving people who are experiencing homelessness something is better than nothing… We′re really trying to flip that script to say that this population deserves just the same amount of resources that everybody else can access. Just because they′re unhoused doesn′t mean that they deserve less. (Director of health initiatives, homeless service organization)

Part of my brain always goes back to classism. It′s just another way people without resources are getting harmed in this country. They don′t even have the ability to die with dignity, and I just can′t think of any other fundamental thing everyone should agree on. (Director, respite service)

I want you to think about [how] these folks are no different than anybody else… It’s always difficult for people to lose control in their lives, but when you’ve spent years having to be on the alert all the time for any kind of danger, and then suddenly you’re in this place where there are people that you don’t know… It can be pretty difficult. (Director, shelter-based organization)

When somebody passes away, we have a memorial service… And I think the craziest part is when people hear about it and providers show up… Hospital people come out and police officers, and first responders, and people that I didn′t even realize whose lives he′s touched… Everyone just told stories about how amazing this guy was. (Lead case manager, permanent supportive housing)

There were resources that should have been available for this person. And [how do you] do what you can to prevent that from happening again? Especially when you tend to care very deeply for the people you work with. (Social worker, outpatient service)

3.2. Theme 2: Prioritizing Individualized, Holistic Care

Guided by their values described in Theme 1, and amid systemic challenges they faced, participants managed to center individualized, holistic care for the unhoused individuals they worked with. Central to this care were building rapport and trust, honoring dignity and autonomy, and advocating for their unhoused clients at the organizational level while addressing stigma among colleagues. In some cases, providers offered examples of how their agency’s organizational commitment to supporting unhoused individuals facilitated these approaches to care.

3.3. Theme 2a. Building Rapport and Trust

Building rapport with clients experiencing homelessness was described as a central component of establishing trusting relationships to better understand individual needs and promote continuity of care. Participants described trust as vital for unhoused individuals who have likely been mistreated in HC service and/or SS and, consequently, may have understandable distrust in providers.

Within a couple months he trusted me and he began to tell me some of the things that were issues in his life that were barriers to him seeking care… He was able to trust me enough to understand that I was trying to help him. (Nurse practitioner, palliative care and geriatrics)

The approach that we take is patient-centered… It′s about showing someone respect no matter what′s going on socially in their life, and proving to them that you care, and showing up. I think being up front just serves as well. It′s a bridge built from both sides. I′m gonna show up and build my side of the bridge. They also have to show up and build their side.. Showing a person respect is still holding them accountable for what their role in their care is.

[We] can follow patients from the ED all the way into the community… Instead of you having to retell your story constantly to new providers, which is a reality at a large metropolitan hospital, you could have one person, hopefully you had really good rapport with, that you knew you could reach out to… You wouldn′t have to retell your story of trauma, which I thought was really important. (Program manager, outpatient service)

3.4. Theme 2b. Honoring Dignity and Autonomy

Honoring dignity and autonomy when working with unhoused individuals was also described as a core approach to care. Providers discussed the importance of showing respect to individuals who have so often been disrespected and discriminated against in their daily encounters within HC and society, while valuing their goals and wishes. A director of a shelter-based service said, “We call ourselves resident-driven. We try to do what the resident wants and needs. They’ve already been traumatized enough.”

I think our team identifying what his goals were. Honoring his dignity and worth and his process… Being on the same page around what his goals were and how did we leverage that to then engage with him more frequently outside of crisis situations so we could help him meet those basic needs. (Social work intern, general hospital)

We do a really good job of meeting people where they’re at… Give them the choice of how much, or how little support they want. Those that want active support in helping to find shelter for them or some place for their care, we fully dive in and try that… But we also respect those that [have] no intentions of ever living anywhere but on the streets. And so, what kind of support can we provide in order for that to happen? (Nurse, hospice organization)

[The] primary care providers are so used to managing [PEOL needs] on their own… Almost making a palliative care plan with the patient, but it’s just their primary care doc that’s saying, “Hey, we’re gonna try to manage just as best as we can.” Because that’s the person they trust and that’s the person that they can go in to see… Maybe they’re not getting specialized palliative or hospice care, but there’s some things being done. Just by other people. (Social worker, family medicine)

3.5. Theme 2c. Advocating for Unhoused Clients

Part of our work is realizing we establish a baseline and a history with a client… We know when new behaviors come up, we can call and say this is new behavior. There’s no way that they are okay… Please re-evaluate. (Director of health initiatives, homeless service organization)

We try really hard to humanize these people because usually they’ve done some amazing stuff… “Did you know that this person did this?”… So that it changes people’s automatic, “She’s just a bipolar, homeless frequent flyer” and trying to take away those labels. We love to find the gems and share them, because it stops people in their tracks. (Nurse practitioner, inpatient palliative care)

3.6. Theme 2d. Organizational Commitment to Supporting Unhoused Individuals

We really live by our mission, which is to be able to meet people where they are and provide end-of-life care how they want it… We try not to say no to anybody. (Nurse, hospice organization)

We have altered our program a bit to cater to some of that barrier. So, if a hospital has a person experiencing homelessness who meets our other criteria and is also hospice appropriate, we will significantly reduce the rate that the hospital pays so that we can assume the role of guardian and get them into the appropriate level of care. (Director of case management, guardianship services)

My leadership team was great at letting me be really intentional with the budget, and I can’t have everything, but they’ve supported this being a really unique, one-of-a-kind environment and one of the better programs in the nation to really promote healing and community. (Director, respite services)

[My colleague] and hospital leadership and some others worked to apply for [funding source] to essentially pay the salaries of myself and [colleagues] to create… a program for people who are experiencing housing deprivation and engaged with services [at the hospital]. (Hospital-based social worker, outpatient service)

3.7. Theme 3: Reimaging Our Systems of Care

Finally, providers described what they saw as necessary solutions to improve PEOL care for unhoused individuals. The interviews identified specialized PEOL services, better housing options, and transforming our overall culture around homelessness and PEOL care as mechanisms for better supporting unhoused individuals with palliative needs.

3.8. Theme 3a. Specialized Palliative and End-of-Life Services for Unhoused Individuals

It’d be really cool to have a hospice facility that specializes in caring for folks that are unhoused. Because it’s different and it takes a different set of training and skills. (Social worker, family medicine)

Having a place for people to go is a big thing… And more people there to help them… The caseloads in all areas are huge for everybody and a lot of people fall through the cracks, especially in the homeless population. If there was more people to go around to help them, that would mean more money for the organization serving them. (Social worker, hospice organization)

Us being able to provide hospice on the street as safe as possible for folks that wanna be there, and then [social model hospice] homes where there′s no kind of structured rules around how that building has to operate. And it′s just funded by donors and there′s great food and therapy dogs… And everyone can hang out by the pool… or whatever they wanna do with their last month or two of life. (Director, respite services)

When I think specifically about folks who are experiencing homelessness that are facing life limiting illness, lack of community is one of the biggest drawbacks and lack of support around the end of life… That′s why I love [local social model hospice home], here is where they can come and here′s where they can be surrounded by people who are offering support. (Death doula, nonprofit organization)

3.9. Theme 3b. Better Housing Options

I do wonder if unhoused individuals would do well living housed… Just having more access to free housing would [address] some of the subpar services that we currently have. (Nurse practitioner, inpatient palliative care)

I would probably start with secure housing, obviously. Housing with specific need housing… I would love to have an onsite medical thing. So, when those small things start, they can get caught. Something like getting blood work done is a huge barrier for a lot of our population. So having an onsite nurse who is able to do those things. (Lead case manager, permanent supportive housing)

If I were to wave a wand, [shelters] would be much more robust. If primary care or complex care physicians could be more present out in community at those places, I think that could be neat… If there was more healthcare professionals meeting people where they are, that could go a long way. (Case manager, permanent supportive housing)

3.10. Theme 3c. Transforming Our Culture

Everyone is deserving of care. Healthcare, housing, those are human rights in my opinion… I think hospice and palliative care are vital, ‘cause people are going to get chronic and fatal illness. All of that is important, but I think there’s a lot of other things that at the very least we need to work on… And that is addressing and mitigating the social and economic forces that hasten the death of poor people and exacerbate and deny care for people with debilitating illness. (Hospital-based social worker, outpatient service)

Transforming our complete medical system so that all the social determinants of health were taken into consideration early on in a person’s life so that there were no people unhoused. A culture shift in our whole country around end of life… that death isn’t a failure. (Nurse practitioner, palliative care and geriatrics)

The first is around community and culture… What does a sense of community, accountability, and safety look like there? Culture of the surrounding community as well. Changing NIMBYism culture. Having productive and meaningful community engagement in a living environment, no matter where that is. (Social work intern, general hospital)

4. Discussion

The findings from this qualitative study remind us of the humanity of individuals enduring homelessness, and the simple, yet imperative notion that everyone is deserving of care. HC and SS providers in the interviews highlighted person-centered care approaches that promote trust, autonomy, and dignity. Our findings build on literature illustrating systemic and organizational barriers to PEOL care for unhoused individuals—and the providers who work with them—and offer opportunities to improve care for these individuals to counter and address current systemic challenges. The following discussion considers systems-level implications that influence PEOL care and homelessness, and how HC and SS providers can engage in value-guided practices despite systemic barriers, including an inhumane lack of resources.

As illustrated in the BMVP, the external environment (including HC and social systems) and enabling factors (including services organizations and their providers who work directly with clients) play critical roles in understanding health services use, and ultimately health outcomes, among unhoused individuals with PEOL needs [41, 42]. While the current study primarily focuses on the role of the provider, the perspectives shared in the interviews implicate organizational and systemic issues that impact the unhoused individuals they work with in addition to their ability to provide care. Alongside many social inequities in the United States, centuries of racism and classism have caused and maintained homelessness, the dehumanization of those experiencing homelessness, and the resulting systemic failures to provide dignifying and quality PEOL care [46–48]. Unsurprisingly, then, the implications and potential solutions to this issue are complex, but not impossible. If anything, our findings highlight that providing humanizing care and garnering organizational support to do so are possible, even while our broader policies and systems have not yet provided the infrastructure to standardize such approaches and eliminate health inequities. The value-guided approaches described within these findings align with antioppressive practices used by social workers in individual case work, such as recognizing injustices and structural barriers, providing care that combats discrimination experienced by clients, critically reflecting on how power is exercised, and maintaining aspirational and long-term goals to advance social justice [49].

Rooting approaches to care in the inherent dignity and worth of unhoused individuals is—disturbingly so—an essential perspective to underscore in the U.S.’s current social and political context surrounding homelessness. Amid societal stigma, homelessness criminalization policies (including the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent Johnson vs. Grants Pass ruling), and continuing evidence of poor health outcomes for these individuals, the reminder that unhoused individuals are “humans that deserve basic care” is an urgent baseline that providers and organizations must operate from to improve outcomes.

Prior work demonstrates that unhoused individuals are commonly dehumanized, and this dehumanization has been linked with public support for harmful antihomelessness policies and punishment for violating such policies [50–52]. Conversely, humanizing and having empathy for unhoused individuals are associated with intentions to help this group. Notably, however, one study suggests the perceived humanity of unhoused individuals is not a predictor of intent to help this group without a concurrent investment in social justice issues [53]. Essentially, perceiving unhoused individuals as human, while necessary, is the bare minimum, and these findings offer actionable care approaches that live into the values of humanizing care and equity in PEOL contexts.

Multiple studies incorporating the perspectives of both unhoused individuals and HC/SS providers have highlighted the importance of trusting relationships between unhoused individuals and the providers they work with, emphasizing rapport, respect, and continuity as key factors in trusting, therapeutic relationships [26, 35, 54]. Such approaches are rooted in core values across multiple health disciplines including nursing, social work, and medicine, including respect for human dignity, beneficence, and justice [55–57].

Yet, our workforce shortage, caseload burden, and workflows often do not offer time and resources for these antioppressive, value-guided practice approaches. Not only does this reinforce and exacerbate poor outcomes among unhoused individuals with life-limiting illness, but also this impacts HC overall. In a system that prioritizes profit over care, how does HC as a field prioritize humanizing and person-centered care for all patients? A focus on solutions and long-term change needs to coincide with these daily practices to improve PEOL care for all patients.

Among the suggested solutions to improving PEOL care for this population, the interviews highlight the importance of PEOL services tailored to the unique needs of individuals experiencing homeless, including street-based or mobile palliative medicine and social model hospice homes. Studies comparing unhoused care recipients’ experiences in primary HC services tailored specifically to the unique needs of unhoused individuals versus nontailored services found that tailored services are more favorable and promote better experiences of care [58, 59]. Because of the unique PEOL needs for individuals experiencing homelessness, tailored services such as social model hospice homes and mobile-based palliative care may allow for the flexibility and approaches beyond “ordinary” palliative practices needed to adequately care for these individuals [10]. Interventions embedding PEOL services within shelters also demonstrated positive results. Staff members that received training about PEOL issues and services for their unhoused clients reported feeling more confident, more knowledgeable, and more prepared to care for clients with serious or life-limiting illness [60, 61]. Another study estimated significant HC savings by offering shelter-based hospice services instead of relying on alternative care locations including hospital settings [62].

Lastly, the findings emphasize the need for better, more affordable housing options, potentially mitigating many challenges experienced by unhoused individuals, including access to PEOL care. Many participants highlighted the need for housing options with wraparound services to include accessible HC. Addressing the issue of homelessness must include multifaceted solutions to represent the complex problems and experiences faced by unhoused individuals—including housing, HC, and community-based supports [63]. Furthermore, it is essential for services supporting seriously ill and/or older adults experiencing homelessness to include accessible housing options with colocated health services, in addition to mobile health to meet individuals where they are [64]. Another study emphasized the need for PEOL support within permanent supportive housing settings, given the increased prevalence of chronic conditions and mortality among unhoused (and formerly unhoused) individuals [65].

HC and SS providers can combine their individual practices with advocacy for HC and housing reforms. Individually, providers can engage in critical reflection to advance awareness of how dynamics of discrimination and social injustices impact everyday care interactions. Given that such critical reflection and awareness is a skill to be developed by professionals [49], supervisors can meaningfully address issues of value-guided practices, power dynamics, and structural forces with clinical staff. Organizational settings can embed reflective practice to learn from negative outcomes and foster authentic, caring interactions with unhoused individuals seeking PEOL care. Attending to these supervisory and organizational levels for solutions is needed to prevent burnout and the numbing of individual providers within PEOL care, given the inhumane, systemic barriers faced by unhoused individuals.

4.1. Limitations

This sample is limited to a racially homogenous group (primarily white) and to the context of Colorado, mostly pertaining to a large metropolitan area with more access to homeless-facing resources than rural or less resourced areas. Additionally, several perspectives were missing from the interviews that may further illuminate the context of PEOL care for unhoused individuals, including those working in EDs, emergency shelters for unhoused individuals, and Federally Qualified Health Centers (including specific Healthcare for the Homeless locations). Future research should explore the perspectives of such providers to better understand how PEOL needs are addressed in ED and Healthcare for the Homeless contexts, where unhoused individuals are likely seeking care most often. Despite these limitations, this study highlights humanizing, realistic approaches to care for unhoused individuals with life-limiting illness and offers opportunities to improve care. Further, this study is the first to our knowledge that examines PEOL care for this population in the state of Colorado outside of the veteran context.

5. Conclusions

Unhoused individuals with life-limiting illness have poor access to PEOL care, and HC and SS providers face multiple systemic challenges to addressing the needs of their seriously ill unhoused clients. Despite this, our findings highlight realistic, person-centered approaches HC and SS providers can incorporate into their daily practices that prioritize trust, dignity, and autonomy among their unhoused patients or clients. By describing these enabling approaches that HC and SS providers used, it is hoped that such practices could be incorporated across health and SS systems. Amid the U.S.’s worsening housing crisis, addressing social and economic inequities that drive homelessness in the first place and creating policies to support more affordable housing solutions are essential. Finally, health and SS organizations should examine how their policies and workflows can better support the complex care needs of unhoused individuals with life-limiting illness—including specialized PEOL programs when possible—in turn supporting their providers who work directly with these individuals.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study was funded by the University of Denver Graduate School of Social Work and Knoebel Institute for Healthy Aging.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.