Enacted Stigma and Adverse Mental Health in Chinese Gay and Bisexual Men

Abstract

Gay and bisexual men face disproportionately higher rates of adverse mental health conditions compared to their heterosexual counterparts. Grounded in the minority stress theory and set within the China’s stigmatized cultural context, this study probes deeply into the mediating roles of proximal minority stressors (including rejection sensitivity and internalized homophobia) and individual coping process (i.e., self-efficacy) in the relationship between enacted stigma and adverse mental health among Chinese gay and bisexual men. Furthermore, it examines the moderating roles of outness to the family on the interrelationships among enacted stigma, proximal minority stressors, and adverse mental health. A total of 728 participants, comprising 334 gay men and 394 bisexual men, completed measures of sociodemographics, enacted stigma, rejection sensitivity, internalized homophobia, self-efficacy, outness to the family, and adverse mental health. Results indicated that enacted stigma was positively associated with adverse mental health, with both rejection sensitivity and internalized homophobia acting as partial mediators. Furthermore, the sequential mediation role via proximal minority stressors and self-efficacy was statistically significant. Notably, the degree of outness to the family moderated not only the relationship between enacted stigma and internalized homophobia but also its indirect link on adverse mental health. These findings provide compelling cross-cultural evidence in support of the minority stress theory and spotlight pivotal intervention pathways aimed at addressing adverse mental health prevalent among Chinese gay and bisexual men.

1. Introduction

Worldwide, gay and bisexual men are confronted with substantially elevated risks of adverse mental health outcomes in comparison to their heterosexual counterparts [1, 2]. Within the gay and bisexual community, the prevalence of depression and anxiety is particularly high and exhibits an upward-trending trajectory [3]. This disparity can be predominantly attributed to external and internal stigma linked to the sexual minority status [4], a situation that is further aggravated within China’s stigmatizing cultural milieu [5].

China’s Confucian culture, deeply anchored in the tenet of “filial piety” and further reinforced by policies such as the previous “one-child” policy and recent “three-child” directive, heightens societal expectations for men to continue the family lineage [6, 7]. As a result, those who deviate from these cultural norms are marginalized [8]. Additionally, the values inherent in Confucianism uphold traditional gender roles and heteronormativity [9], thereby intensifying the rejection faced by gay and bisexual men from both society and family. Moreover, the precedence given to social and family harmony over individual autonomy exposes gay and bisexual men to discrimination and suppression, as their sexual orientation is often seen to threaten the cultural imperative of “face” (mianzi in Chinese), a construct tied to both self-perception and external evaluation [10]. This cultural construct emphasizes maintaining family honor and social reputation through conformity to social norms [11], which can stigmatize not only the individual but also the entire families, leading to collective shame and humiliation [10]. To preserve face, parents often pressure their children into heterosexual marriage and childbearing, rather than offering support for their sexual orientation [12]. These perceptions amplified internalized stigma and psychological distress, frequently resulting in identity suppression, confusion, and a sense of aimlessness [11].

Notwithstanding these challenges, in contrast to Western research, empirical evidence exploring the relationship between sexual minority stigma and adverse mental health in Eastern cultural contexts, especially in China, is growing but limited [7, 13–19]. In particular, studies addressing enacted stigma and its consequences are notably scarce. Grounded in the minority stress theory, this study investigates how enacted stigma—as the behavioral manifestation of distal sexual minority stigma, defined as the experience of discrimination, harassment, threats, and criminal victimization directly related to one’s sexual identity [20, 21]—is linked to the adverse mental health of Chinese gay and bisexual men, with a particular emphasis on proximal minority stressors as mediators. It also explores the sequential mediation role through proximal minority stressors and self-efficacy. Considering the specificities of China, the study further examines the moderating roles of outness to the family in shaping adverse mental health.

2. Background

2.1. Enacted Stigma and Adverse Mental Health

Meyer [22] proposed the minority stress theory, positing that LGB individuals in a heterosexist society endure minority stress stemming from their stigmatized social status. This minority stress encompasses both distal and proximal factors related to discrimination and marginalization, with sexual minority stigma serving as the fundamental stressor. Specifically, actual prejudice events, such as housing or employment discrimination and victimized violence such as being bullied, were elaborated into the concept of distal minority stress [4]. Herek [20] argued that enacted stigma is visibly demonstrated through interpersonal actions against the LGB communities, including antigay remarks, slurs, social exclusion, ostracism, and overt acts of discrimination or violence [20, 21]. Gower et al. [23] provided further insights into the experiences of enacted stigma among LGB youth across various settings, especially in schools and communities. These experiences of enacted stigma cover a wide array of victimization forms, including microaggressions and microinsults (e.g., witnessing anti-LGB jokes, slang, or misgendering), verbal harassment (e.g., name-calling or disapproval of sexual orientation or gender identity), and physical violence (e.g., being beaten, strangled, or threatened with violence). As previously emphasized, gay and bisexual men in China encounter a complex and multifaceted stigmatized cultural context. To measure distal sexual minority stigma endured by this specific population, the China MSM stigma scale, an instrument tailored to the cultural context, was developed [24]. This scale effectively captures the objective manifestations of discrimination, violence, and prejudice that sexual minority men encounter and is frequently utilized within China’s unique sociocultural context [14, 25].

Extensive research has underscored the detrimental effects of distal minority stress on the mental health of gay and bisexual men [14, 26–28]. Recent empirical research has further emphasized the nuanced role of enacted stigma in exacerbating mental health issues. For example, it has been associated with depression and anxiety [29–32] and has been found to create barriers to accessing care [33]. A qualitative interview study with LGBTQ + youth revealed that enacted stigma compelled individuals to modify their daily routines, restrict movements, and limit participation in extracurricular and socialization opportunities [23]. Additionally, Swann et al. [34] demonstrated that enacted stigma from multiple minority identities increased the risk of intimate partner violence among sexual minority youth of color. In China, a 4-year cohort study found that enacted stigma could directly affect depressive symptoms among MSM [35].

Frost and Meyer [36] have emphasized the necessity of culturally specific components to refine the minority stress model and enhance its applicability across diverse cultural contexts. However, studies specifically focusing on Chinese gay and bisexual men remain limited, particularly in exploring the underlying mediating mechanisms connecting enacted stigma with adverse mental health within China’s distinct cultural context. Bridging this research gap is crucial for understanding how culturally embedded norms and values influence the stressful minority experiences and the effects of mental health challenges faced by this population.

2.2. Mediating Roles of Proximal Minority Stressors

The minority stress theory further posits that distal minority stress may indirectly affect mental health outcomes through proximal minority stressors. These proximal minority stressors are inherently subjective, as they rely on individual perceptions and appraisals [4]. Rejection sensitivity, which is defined as the anxious expectation of rejection and a heightened tendency to perceive and interpret ambiguous interpersonal behaviors as rejection, encompasses the affective and behavioral responses of individuals to external stigma [37]. Internalized homophobia, described as “the direction of societal negative attitudes toward the self”, represents a form of negative self-cognitive internal stigma among sexual minority individuals [22]. Empirical evidence has consistently demonstrated an association between proximal minority stressors and adverse mental health among gay and bisexual men [19, 38].

In addition, proximal minority stressors have been identified as mediators linking distal minority stress to internalizing symptoms [39, 40]. The perceived experiences of discrimination and prejudice have been shown to correlate with increased rejection sensitivity and internalized homophobia [27]. A 6-month longitudinal study found that enacted bi + stressors consistently predicted increases in anxiety and depression, with internalized and anticipated bi + stigma mediating this relationship [41]. While research in non-Western societies is limited, existing studies indicated that enacted stigma could amplify proximal minority stressors, thereby exacerbating adverse mental health challenges, particularly in China [14, 35]. However, the underlying mechanisms of proximal minority stress in the relationship between enacted stigma and adverse mental health remain underexplored, especially when it comes to Chinese gay and bisexual men. This research gap underscores the need for further investigation to clarify these mechanisms and offer culturally relevant insights for mental health interventions.

2.3. Sequential Mediation Effect of Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy, a core component of the coping framework of the minority stress theory, operated as an individual coping mechanism, enabling sexual minority individuals to navigate self-stigma and its resultant mental health conditions by effectively appraising challenges and mobilizing resources to mitigate proximal minority stressors [4, 42]. Defined as an individual’s belief in their ability to organize and execute actions essential for managing prospective challenges [43], self-efficacy has been identified as a mediator between distal stress and depressive symptoms in the general population [44]. Guided by the minority stress theory, Frost and Meyer [36] explicitly posit that the negative impact of stressful experiences and the ameliorative effect of individual-level coping interact to predict the overall health outcomes. Among sexual minority men, lower self-efficacy has been associated with greater psychological distress [45]. For instance, problem-focused coping self-efficacy has been found to mediate the association between perceived stigma and psychological distress among sexual minority people of color [46]. Similarly, internalized homophobia has been shown to reduce self-efficacy, which in turn predicts more severe depression symptoms [47]. Drawing on nationally recruited nonclinical samples of LGB adults, Denton et al. [27] identified a serial mediation pathway from distal minority stressors to proximal minority stressors, to coping self-efficacy, and ultimately to physical health symptom severity. Supporting this framework, a recent study in China among MSM demonstrated a full mediation pathway from intimate partner violence victimization to depression via homosexual self-stigma and self-efficacy [48]. Despite such evidence, the potential mediating role of self-efficacy (the individual coping process) between proximal minority stressors and adverse mental health among gay and bisexual individuals in China remains underexplored, highlighting the necessity for further research in this domain.

2.4. Moderating Effect of Outness to the Family

Outness, which is defined as the extent to which sexual minority individuals disclose their sexual orientation, serves as a behavioral indicator of stigma adaptation [49]. Its impact is context-contingent, being shaped by relational, sociocultural, and environmental factors [50]. Within the minority stress theory, Frost and Meyer [36] conceptualized outness as a community-level resource situated along the distal-proximal continuum, reflecting how external social structures influence individuals through the process of socialization [4, 36]. The sexual identity development theory further posits that outness fosters a positive sexual identity [51], buffering individuals by enhancing self-acceptance and reducing internalized homophobia [4]. While outness could enhance social support and contribute to an individual’s well-being, it also exposes them to an increased risk of victimization and interpersonal microaggressions [52, 53]. In structurally stigmatized contexts, outness often correlates with worse mental health outcomes, while having less negative impact in more supportive settings [29].

In China’s cultural context, disclosing one’s sexual orientation, especially to family members, often elicits discrimination or rejection rather than understanding or support [54]. Parents who uphold Confucian traditional gender roles frequently perceive their children’s sexual identity as shameful or even pathological conditions, responding with overt anger, doubt, or violence in attempts to “normalize” them. Furthermore, high levels of outness to the family have been shown to strengthen the link between distal stress (such as childhood sexual abuse) and internalized homophobia, thereby exacerbating the indirect relationship between childhood sexual abuse and suicidal risks among Chinese gay and bisexual men [55]. A previous study also found that outness strengthened the positive association between traditional Confucianism and proximal minority stressors, further exacerbating depressive symptoms [25]. Although interpersonal disclosures and emotional expression are generally crucial for maintaining mental health [56], the pervasive stigma surrounding sexual minority individuals in China complicates this process. Thus, we hypothesize that in the Chinese cultural context, high levels of outness may amplify the adverse mental health impacts of enacted stigma, both directly and indirectly through proximal minority stressors.

2.5. The Present Study

In this study, we examined a moderated mediation model to investigate the underlying mechanisms linking enacted stigma with adverse mental health among Chinese gay and bisexual men. Specifically, we explored the mediating roles of proximal minority stressors (including rejection sensitivity and internalized homophobia) and the individual coping process (i.e., self-efficacy), along with the moderating roles of outness to the family within this relationship. We hypothesized that (H1) enacted stigma is positively associated with adverse mental health; (H2) proximal minority stressors, including rejection sensitivity and internalized homophobia, mediate the relationship between enacted stigma and adverse mental health; (H3) enacted stigma is indirectly associated with adverse mental health through the sequential mediation of proximal minority stressors and self-efficacy; (H4) outness to the family moderates the associations between enacted stigma and proximal minority stressors, as well as the indirect effects of enacted stigma on adverse mental health via proximal minority stressors; and (H5) outness to the family moderates the direct relationship between enacted stigma and adverse mental health.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sichuan University. We conducted a cross-sectional survey from March to June 2020. Recruitment was carried out via Chinese social networking platforms (including Baidu Post-Bar, Douban groups, and Sina Weibo) and applications (including WeChat and QQ). Detailed descriptions of the recruitment process and data collection procedures have been previously reported [57]. Prior to participants’ completion of the online questionnaire hosted on the Wenjuanxing survey website, informed consent was obtained from all of them. Eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) self-identifying as gay or bisexual men; (2) being 18 or above; and (3) residing in mainland China. Upon completion, participants received 15 CNY (approximately 2.5 USD) as compensation via their Alipay accounts. Data from participants who did not complete or submit the questionnaire were not collected, resulting in no missing data in the present study [25].

The initial sample comprised 810 male participants who self-identified as gay or bisexual men. After excluding individuals under the age of 18 (n = 67), did not report their age (n = 3), and residing abroad (n = 12), the final sample was composed of 728 participants aged between 18 and 40 years (M = 22.86, SD = 4.15). Among them, 334 (45.9%) were gay men, and 394 (54.1%) were bisexual men. Most participants had a college degree or higher (n = 619, 85.0%), with an annual income of less than 60,000 CNY (approximately 8300 USD, n = 543, 74.6%). They mainly resided in provincial capitals (n = 238, 32.7%) or megalopolis (n = 213, 29.3%). Additionally, 40.9% of the participants were enrolled as students (n = 298).

3.2. Measures

Enacted stigma was assessed using the enacted stigma subscale of the China MSM stigma scale [24]. This six-item subscale was designed to evaluate participants’ direct experiences of violence and discrimination. Incidents covered by these items included physical violence, loss of housing, and loss of a job due to their sexual orientation. Items were rated on a four-point Likert scale (1 = never, 2 = once or twice, 3 = a few times, and 4 = many times), with higher scores representing a higher level of enacted stigma. The scale has been previously utilized among sexual minority men [14, 58] and has shown satisfactory internal consistency and strong construct validity. In the present study, Cronbach’s α was 0.90.

Rejection sensitivity was assessed using the gay-related rejection sensitivity scale [59], which encompassed 14 items. Each item delineated a specific scenario in which participants might potentially encounter rejection due to their sexual orientation (e.g., “You are in a locker room in a straight gym. One guy nearby moves to another area to change clothes.”). Participants first rated how concerned or anxious they would feel if such a situation occurred due to their sexual orientation (1 = very unconcerned to 6 = very concerned). Then, they rated the likelihood of each situation occurring due to their sexual orientation (1 = very unlikely to 6 = very likely). The total scores for the two subscales were multiplied, with higher values indicating a greater degree of rejection sensitivity. The Chinese version was translated by Xu et al. [40]. In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.96.

Internalized homophobia was evaluated using the nine-item internalized homophobia scale [22]. Participants responded to statements such as “I feel that being gay/bisexual is a personal shortcoming.” on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating a higher level of internalized homophobia. Previous studies have demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency for this scale [25, 60]. In the present study, Cronbach’s α was 0.93.

Self-efficacy was assessed using the generalized self-efficacy scale [61]. This 10-item scale evaluates individuals’ confidence and ability to cope with challenging or stressful situations. An example item is “I can always manage to solve difficult problems if I try hard enough.” Responses were recorded on a four-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree), with higher scores reflecting a greater degree of self-efficacy. This scale has displayed acceptable internal reliability and construct validity among gay and bisexual individuals [27]. The Chinese version of this scale was translated by Wang et al. [62]. In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.91.

Outness to the family was assessed using a four-item subscale of the outness inventory originally developed by Mohr and Fassinger [63] and adapted by Xu et al.’s team [25, 55]. Participants gauged the degree to which they had disclosed their sexual minority orientation to their mother, father, siblings, and other family members on a five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 2 = probably does not know but never talked about, 3 = probably knows but never or rarely talked about, 4 = definitely knows and sometimes talked about, and 5 = completely disclose and openly talked about), with higher scores indicating a greater level of “outness” within their family networks. The Chinese version of this scale was translated by Xue and Xu [55]. For our sample, the Cronbach’s α was 0.89.

Adverse mental health was evaluated by the short version of the depression anxiety stress scale [64], which comprised 21 items. DASS measured three dimensions—depression, anxiety, and stress—to evaluate participants’ overall adverse mental health outcomes. Example items include “I felt downhearted and blue.” for depression; “I was aware of dryness of my mouth.” for anxiety; and “I found it hard to wind down.” for stress. Participants rated each item on a four-point Likert scale (1 = it did not apply to me at all to 4 = it applied to me most of the time), and higher aggregated scores across the respective subscales indicated more severe adverse mental health outcomes. The Chinese version of the DASS has demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity in previous research [65, 66]. In this study, Cronbach’s α for depression, anxiety, and stress subscales was 0.90, 0.87, and 0.87, respectively.

3.3. Statistical Analyses

Data analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 22.0 and AMOS 22.0 software. To validate the latent construct of adverse mental health, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed, with depression, anxiety, and stress serving as observed indicators. Sociodemographics, including age, education, occupation, annual income, and location, were incorporated as covariates in the analysis [67]. First, descriptive statistics were computed for the main variables, and differences between self-identified gay and bisexual men were examined using the independent sample t-test and the Chi-square test. Second, bivariate correlations and partial correlations (H1) were tested. Third, structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to explore the relationship between enacted stigma and adverse mental health, with a particular focus on the mediating roles of proximal minority stressors (H2) and the sequential mediation involving proximal minority stressors and self-efficacy (H3). Fourth, outness to the family was integrated into the mediation model as a moderating variable to examine its respective potential effects (H4 and H5). A 95% bootstrapped confidence interval (CI) was calculated based on 5000 bootstrapped samples. Mediation effects were considered significant if the 95% CI excluded zero, while moderation effects were deemed significant if the 95% CI for the interaction term did not contain zero [60].

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 outlines the sociodemographics and core variables’ characteristics of the sample. The mean scores and standard deviations for other psychosocial variables in the entire sample were as follows: enacted stigma (M = 10.88, SD = 5.02), rejection sensitivity (M = 200.12, SD = 107.16), internalized homophobia (M = 24.35, SD = 9.22), self-efficacy (M = 26.49, SD = 6.02), and outness to the family (M = 8.89, SD = 4.93). Bisexual men generally reported higher levels across variables compared to gay men. Significant differences were observed between gay and bisexual men for depression and anxiety, except for stress.

| Gay men n = 334 | Bisexual men n = 394 | t/χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 23.30 (4.39) | 22.49 (3.91) | −2.43∗ |

| Education, N (%) | |||

| Senior higher or lower | 32 (9.6) | 77 (19.5) | 16.86∗∗ |

| College | 255 (76.3) | 282 (71.6) | |

| Postgraduate or higher | 47 (14.1) | 35 (8.9) | |

| Occupation, N (%) | |||

| Student | 153 (45.8) | 145 (36.8) | 6.06∗ |

| Nonstudent | 181 (54.2) | 249 (63.2) | |

| Annual income, N (%) | |||

| < ¥60,000 | 243 (72.8) | 300 (76.1) | 8.93∗ |

| ¥60,000–¥100,000 | 29 (8.7) | 49 (12.5) | |

| > ¥100,000 | 62 (18.6) | 45 (11.4) | |

| Location, N (%) | |||

| Rural area | 16 (4.8) | 20 (5.1) | 9.92∗ |

| Urban area | 32 (9.6) | 20 (5.1) | |

| General city | 73 (21.9) | 116 (29.4) | |

| Provincial capital | 109 (32.6) | 129 (32.7) | |

| Megalopolis | 104 (31.1) | 109 (27.7) | |

| Enacted stigma, M (SD) | 9.58 (4.41) | 11.99 (5.24) | −6.11∗∗∗ |

| Rejection sensitivity, M (SD) | 172.99 (100.7) | 223.12 (107.2) | −6.54∗∗∗ |

| Internalized homophobia, M (SD) | 20.79 (8.66) | 27.37 (8.59) | −9.86∗∗∗ |

| Self-efficacy, M (SD) | 25.72 (5.97) | 27.14 (6.00) | −3.01∗∗ |

| Outness to the family, M (SD) | 8.04 (4.48) | 9.62 (5.17) | −4.05∗∗∗ |

| Adverse mental health, M (SD) | |||

| Depression | 8.57 (5.51) | 9.89 (5.23) | −3.58∗∗∗ |

| Anxiety | 8.42 (4.93) | 10.22 (5.01) | −5.00∗∗∗ |

| Stress | 10.18 (5.08) | 10.75 (4.76) | −1.74 |

- ∗p < 0.05.

- ∗∗p < 0.01.

- ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

4.2. Preliminary Analyses

Table 2 presents the bivariate and partial correlations among core variables. The results indicated that enacted stigma was positively associated with all adverse mental health dimensions including depression, anxiety, and stress, supporting H1. Furthermore, both rejection sensitivity and internalized homophobia were positively correlated with self-efficacy and all adverse mental health dimensions. Self-efficacy was positively associated with anxiety but did not exhibit a statistical association with depression or stress. Outness to the family was positively associated with enacted stigma and adverse mental health dimensions.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Enacted stigma | 1 | 0.54∗∗ | 0.57∗∗ | 0.26∗∗ | 0.51∗∗ | 0.46∗∗ | 0.50∗∗ | 0.37∗∗ |

| 2. Rejection sensitivity | 0.56∗∗ | 1 | 0.48∗∗ | 0.20∗∗ | 0.26∗∗ | 0.36∗∗ | 0.42∗∗ | 0.33∗∗ |

| 3. Internalized homophobia | 0.60∗∗ | 0.49∗∗ | 1 | 0.24∗∗ | 0.23∗∗ | 0.33∗∗ | 0.42∗∗ | 0.31∗∗ |

| 4. Self-efficacy | 0.28∗∗ | 0.21∗∗ | 0.25∗∗ | 1 | 0.23∗∗ | −0.04 | 0.10∗∗ | −0.01 |

| 5. Outness to the family | 0.56∗∗ | 0.29∗∗ | 0.29∗∗ | 0.25∗∗ | 1 | 0.31∗∗ | 0.30∗∗ | 0.24∗∗ |

| 6. Depression | 0.48∗∗ | 0.38∗∗ | 0.37∗∗ | −0.03 | 0.33∗∗ | 1 | 0.79∗∗ | 0.79∗∗ |

| 7. Anxiety | 0.52∗∗ | 0.44∗∗ | 0.44∗∗ | 0.10∗∗ | 0.32∗∗ | 0.80∗∗ | 1 | 0.83∗∗ |

| 8. Stress | 0.37∗∗ | 0.34∗∗ | 0.32∗∗ | −0.01 | 0.24∗∗ | 0.79∗∗ | 0.83∗∗ | 1 |

- Note: Bivariate correlations are below the diagonal, and partial correlations controlling for age, education, occupation, annual income, and location are placed above.

- ∗∗p < 0.01.

The latent construct of adverse mental health, measured by depression, anxiety, and stress, demonstrated strong intercorrelations among its components (r > 0.78, p < 0.001), high factor loadings (0.93, 0.94, and 0.93, respectively), excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.92), and robust reliability and convergent validity (CR = 0.95, AVE = 0.87). The KMO and Bartlett’s test (KMO = 0.76, χ2 = 1687.89, df = 3, p < 0.001) confirmed the factorability of the data.

4.3. Mediating Roles of Multiple Variables

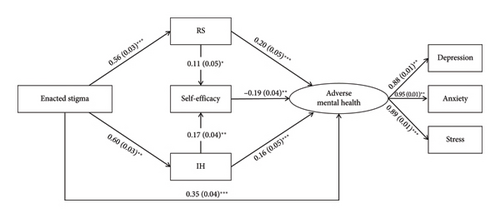

The model demonstrated an acceptable fit to the data, χ2 /df = 4.58, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.96, NFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.07, and 90% CI = [0.06, 0.08]. Mediation analyses confirmed a significant total effect of enacted stigma on adverse mental health (β = 0.53 [0.47, 0.59], p < 0.001). After including mediators, the direct role of enacted stigma on adverse mental health remained significant (β = 0.35 [0.27, 0.44], p < 0.001). As depicted in Figure 1, enacted stigma was significantly associated with rejection sensitivity (β = 0.56 [0.50, 0.61], p < 0.001) and internalized homophobia (β = 0.60 [0.55, 0.65], p < 0.01). Additionally, adverse mental health was significantly associated with both rejection sensitivity (β = 0.20 [0.11, 0.29], p < 0.001) and internalized homophobia (β = 0.16 [0.07, 0.25], p < 0.001). Furthermore, self-efficacy was positively associated with rejection sensitivity (β = 0.11 [0.02, 0.20], p < 0.05) and internalized homophobia (β = 0.17 [0.08, 0.25], p < 0.01), while negatively associated with adverse mental health (β = −0.19 [−0.27, −0.11], p < 0.01).

As summarized in Table 3, the indirect roles revealed that enacted stigma was associated with adverse mental health through rejection sensitivity (β = 0.11 [0.06, 0.17], p < 0.001) and internalized homophobia (β = 0.10 [0.04, 0.15], p < 0.01), supporting H2. Additionally, the sequential mediation role via rejection sensitivity and self-efficacy (β = −0.01 [−0.03, 0.00], p < 0.05) and via internalized homophobia and self-efficacy (β = −0.02 [−0.03, −0.01], p < 0.001) was both significant, supporting H3. These mediating pathways accounted for 20.9%, 18.3%, −2.2%, and −3.7% of the total effect, respectively, highlighting the pivotal roles of proximal minority stressors and self-efficacy in linking enacted stigma with adverse mental health.

| Paths | β | SE | 95% CI | Proportional mediation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ES ⟶ RS ⟶ AMH | 0.11∗∗∗ | 0.03 | [0.06, 0.17] | 20.9 |

| 2. ES ⟶ IH ⟶ AMH | 0.10∗∗ | 0.03 | [0.04, 0.15] | 18.3 |

| 3. ES ⟶ RS ⟶ self-efficacy ⟶ AMH | −0.01∗ | 0.01 | [−0.03, −0.00] | −2.2 |

| 4. ES ⟶ IH ⟶ self-efficacy ⟶ AMH | −0.02∗∗∗ | 0.01 | [−0.03, −0.01] | −3.7 |

| 5. Total effect | 0.53∗∗∗ | 0.03 | [0.47, 0.59] | |

| 6. Direct effect | 0.35∗∗∗ | 0.04 | [0.27, 0.44] | 66.0 |

| 8. Total indirect effect | 0.18∗∗∗ | 0.03 | [0.11, 0.24] | 33.3 |

- Note: Reported effects were all standardized.

- Abbreviations: AMH, adverse mental health; ES, enacted stigma; IH, internalized homophobia; RS, rejection sensitivity; SE, standard error.

- ∗p < 0.05.

- ∗∗p < 0.01.

- ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

4.4. Moderating Effect of Outness to the Family

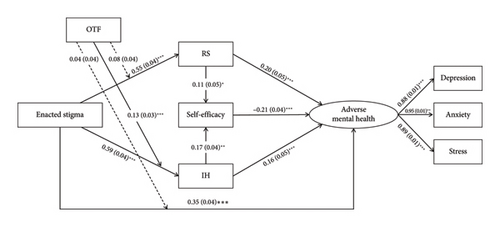

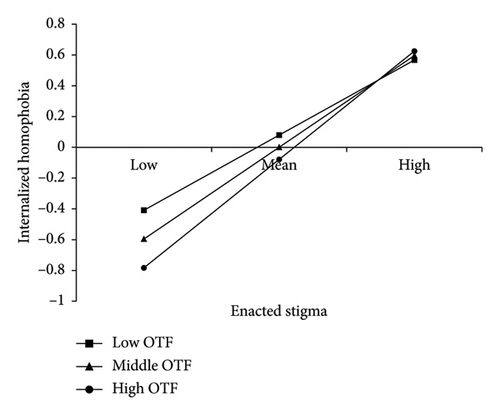

After incorporating the moderating variables, the model demonstrated an acceptable fit to the data, χ2/df = 4.46, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.96, NFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.07, and 90% CI = [0.06, 0.08]. As shown in Figure 2, outness to the family significantly moderated the link between enacted stigma and internalized homophobia (β = 0.13, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001) but not the associations with rejection sensitivity or adverse mental health, thus failing to support H5. Figure 3 illustrated that the relationship between enacted stigma and internalized homophobia was stronger at high outness levels (+1 SD, β = 0.69, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001) compared to middle (0 SD, β = 0.60, SE = 0.04, p < 0.01) or low levels (−1 SD, β = 0.50, SE = 0.06, p < 0.01). The significant moderated mediation index (β = 0.003 [0.001, 0.006], SE = 0.001) indicated that outness to the family strengthened the indirect link between enacted stigma and adverse mental health via internalized homophobia, supporting H4.

5. Discussion

Grounded in the minority stress theory and set within the distinct stigmatized cultural context, this study endeavored to conduct an in-depth exploration of the underlying mechanisms linking enacted stigma—a fundamental manifestation of distal minority stress—with adverse mental health through the mediating roles of proximal minority stressors (including rejection sensitivity internalized homophobia) and individual coping process (i.e., self-efficacy) and the moderating roles of outness to the family among Chinese gay and bisexual men. Participants who experienced higher levels of enacted stigma, rejection sensitivity, internalized homophobia, and lower levels of self-efficacy reported significantly more adverse mental health outcomes. Importantly, our findings identified rejection sensitivity and internalized homophobia as mediators linking enacted stigma with adverse mental health, with a sequential mediation pathway involving proximal minority stressors and self-efficacy. Additionally, outness to the family emerged as a critical moderator in the mediating model.

5.1. Enacted Stigma and Adverse Mental Health

To our knowledge, this study is the first to identify a positive association between enacted stigma and adverse mental health among Chinese gay and bisexual men, which is consistent with evidence from the West countries [29, 30, 32]. Furthermore, Dyar [68] highlighted that chronic stigma exposure amplified the negative emotional impact of daily enacted stigma, leading to greater increases in anxious and depressed effect. In China’s stigmatized cultural context, sexual minority individuals especially men are frequently perceived as deviating from Confucian traditional gender roles and the heterosexual norm [9], exposing them to widespread discrimination and violence [69]. In addition, their perceived inability to fulfill filial obligations, such as continuing the family line, is seen as a violation of Confucian-centered filial piety culture [6, 11], which is believed to disrupt familial and societal harmony. These perceptions have exacerbated public misunderstanding, fear, and prejudice, further marginalizing this group. Structurally, the absence of legal protections and the persistence of discriminatory practices in employment and marriage also contribute to the intensification of enacted stigma [70]. The stress of distal sexual minority stigma imposes profound psychological burdens on gay and bisexual men, significantly affecting their mental health and overall well-being. This study applied the enacted stigma scale in the Chinese context [24], which was specifically designed to capture enacted stigma experiences of Chinese gay and bisexual men. The findings not only validated the scale’s applicability but also provided novel cross-cultural empirical support for the minority stress theory, highlighting the importance of addressing enacted stigma within both local and global frameworks to improve the mental health of sexual minority individuals.

5.2. Mediating Roles of Proximal Minority Stressors

In this study, participants who experienced higher levels of enacted stigma reported increased proximal minority stress (including rejection sensitivity and internalized homophobia), aligning with prior research [27, 35]. As posited by the minority stress theory, minority stressors are unique, chronic, and socially constructed, with proximal minority stressors arising internally as a response to distal minority stress [4, 36]. Gay and bisexual men who are exposed to enacted stigma are particularly vulnerable to sociocognitive challenges, including physical violence, job loss, and daily discrimination [20, 23]. These distal sexual minority stigma experiences contribute to negative self-appraisals, fostering rejection-related cognitive biases [71] and deeply ingrained negative self-perception, cognition, and emotion processes [72]. Ultimately, this leads to an increase in both rejection sensitivity and internalized homophobia. Notably, rejection sensitivity and internalized homophobia mediated the relationship between enacted stigma and adverse mental health. This is consistent with the findings of Sun et al. [14] and Dyar et al. [41], who found that enacted stigma heightened sexual identity concerns, thereby resulting in adverse mental health conditions.

5.3. Sequential Mediation Roles of Proximal Stressors and Self-Efficacy

This study uncovered a significant sequential mediation effect of proximal minority stressors and self-efficacy in the relationship between enacted stigma and adverse mental health. As the individual coping process, self-efficacy served as an effective psychological intervention strategy to mitigate the detrimental effects of both external and internal stigma [26]. Consistent with prior findings among transgender and gender-diverse individuals, coping self-efficacy played a buffering role in mitigating stress-related effects [73]. However, diverging from previous studies [46, 47], the present research found that higher levels of rejection sensitivity and internalized homophobia were associated with higher self-efficacy, which in turn was linked to lower levels of adverse mental health. One possible explanation is that exposure to external stress may activate individuals’ subjective agency and self-motivation. A qualitative study among racially and ethnically diverse sexual minority adolescents described various voluntary engagement coping strategies, including cognitive self-talk, self-encouragement, and the development of a resilient self-concept—such as the sentiment “They don’t accept me, so I’ll just have to keep on moving forward.” [74]. Another possible explanation relates to cultural context. In Chinese culture, stress may paradoxically enhance self-efficacy. A large-scale three-wave longitudinal study showed that daily stress predicted improved mental health by fostering self-efficacy as part of an adaptive stress response mechanism [75]. Similarly, following a high-pressure postearthquake context, some Chinese researchers reported enhanced self-efficacy through successful coping, which improved both their performance and resilience [76]. In addition, individuals with high self-efficacy tend to exhibit better mental health outcomes in stigmatizing contexts, as they are more adept at mobilizing resources and seeking support [27]. These findings highlight the protective role of self-efficacy in buffering the impact of sexual minority stigma on mental health among gay and bisexual men, emphasizing its importance as a target for interventions aimed at improving the well-being of this marginalized population.

5.4. Moderating Effects of Outness to the Family

Outness to the family was found to amplify the direct link between enacted stigma and internalized homophobia, intensifying its indirect role on adverse mental health, while showing no significant moderating role on rejection sensitivity. This finding is consistent with prior research highlighting outness as a double-edged sword, potentially increasing exposure to discrimination and violence and serving as a risk factor for minority stress in high-stigma contexts [77]. In China’s Confucian framework, coming out disrupts traditional expectations such as “continuing the family line” and posing a threat to the family’s and society’s concept of “face” [6, 54], amplifying internalized homophobia among gay and bisexual men. Furthermore, Liu et al. [78] showed that the disclosure to parents and high disclosure profiles had higher enacted stigma from the family than the disclosure to the world and low disclosure profiles among Chinese LGB adults. Consequently, many Chinese sexual minority men remain closeted or partially disclose their identity to their parents. This behavior further strengthens the link between sexual minority identity and internalized homophobia, thereby exacerbating the negative impacts on mental health [55]. A study of 435 gay and bisexual men in southwestern China found that internalized homophobia was positively associated with the concealment of sexual identity to parents and others [19], suggesting that identity concealment itself may be both a consequence and a contributing factor of internalized oppression. Understanding the interplay between family support and outness can inform targeted interventions to improve the mental health of gay and bisexual men, particularly in the Chinese context.

5.5. Implications

This study puts forward recommendations at the societal, interpersonal, and individual levels to promote the well-being of gay and bisexual men. In China, while homosexuality is not a criminal offense, the lack of antidiscrimination laws leaves gay and bisexual men exposed to potential right violations. Enacting scientifically informed antidiscrimination legislation is crucial to explicitly protect sexual minority men from discrimination and violence, promote equality, and foster social harmony. At the societal level, public education initiatives are necessary to reduce prejudice and discrimination. This can be achieved by increasing awareness of sexual orientation diversity through media campaigns, school-based education programs, and community-led activities. Creating a supportive environment requires fostering understanding and inclusivity. Moreover, societal education should mitigate the psychological and social implications of “marriages of convenience” to improve the quality of life within the sexual minority community. On the individual level, psychological support services should be provided to help sexual minority individuals achieve self-acceptance and develop effective coping strategies for managing the negative emotions associated with stigma-related experiences, thereby enhancing their coping self-efficacy. Interventions should also extend to their families, particularly parents, to foster understanding and acceptance, thereby strengthening family support systems, alleviating psychological burdens, and promoting social cohesion. In conclusion, a coordinated, multilevel approach that integrates legislation, societal education, and individual and familial support is indispensable for reducing sexual minority stigma and improving mental health conditions for gay and bisexual men.

5.6. Limitations

Nevertheless, several limitations should be noted. First, its cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences, and the moderated mediation analyses are exploratory. Longitudinal studies are needed to confirm these findings. Second, the online recruitment method may restrict generalizability, as the sample primarily consisted of younger participants, students, and those with higher education. These results may not fully represent older or less-educated sexual minority men in China. Finally, all measures were self-reported, introducing potential biases such as recall and social desirability bias. Future research should adopt longitudinal designs, diverse sampling methods, and interviewer-administered assessments to enhance validity and generalizability.

6. Conclusion

Within the stigmatized cultural context of China, gay and bisexual men encounter severe sexual minority stress, placing a heavy burden on their mental health. High levels of distal minority stress (i.e., enacted stigma) and proximal minority stressors (including rejection sensitivity and internalized homophobia) are positively associated with adverse mental health. Rejection sensitivity and internalized homophobia mediate the relationship between enacted stigma and adverse mental health. A significant sequential mediation role revealed that proximal minority stressors and self-efficacy shape adverse mental health, with high self-efficacy buffering the impact of enacted stigma. Additionally, outness to the family amplifies both the direct role of enacted stigma on internalized homophobia and its indirect role on adverse mental health. This study provides cross-cultural evidence for the minority stress theory and offers important implications for clinical practice and policy development aimed at protecting the rights of gay and bisexual men in China.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The project was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (22CSH050), the Key Laboratory of Smart Policing and National Security Risk Governance 2024 Project (ZHKFYB2403), Sichuan University Youth Outstanding Talent Cultivation Project (SKSYL2023-08), Sichuan University Innovation Research Project (2023CX26), and Scientific Research Planning Project of Sichuan Psychological Association (SCSXLXH20240001).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Miss Yuxia Huang for her help in participant recruitment. The authors also thank all participants of this study.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.