Parents’ Experiences of Accessing Support for Adversities that Impact Their Parenting: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Evidence

Abstract

Adversities during childhood such as experiences of neglect, parental mental illness, substance use, financial stress, unstable housing and racism/discrimination have cumulative and harmful lifelong impacts. Early identification, intervention and support for parents, families and communities experiencing adversity can enhance their capacity to provide environments where children can thrive and reach their full potential. However, parents experience many barriers to seeking support including experiences of judgement, blame and discrimination when accessing services. This systematic review of qualitative evidence aimed to explore parents’ experiences of interactions with health, welfare and educational professionals when accessing support for adversities that impact parental capacity and children’s health, development or wellbeing in the early years (0–5 years). In doing so, we specifically aimed to explore elements of professionals’ interactions that parents viewed either positively or negatively to inform future policy, practice, education and research. After the screening process, 16 studies were included in the synthesis. Key findings highlighted that although health and welfare services should be promoting parental capacity to raise thriving children, parents frequently experienced professionals who were unwilling to listen, disrespectful and restricted parents’ participation. Furthermore, parents felt the complexity of their lives was not acknowledged and felt blamed for broader socioeconomic circumstances and intergenerational patterns of marginalisation. Conversely, positive experiences came from professionals who engaged in genuine relationships that provided emotional and practical supports that empowered parents to change. These findings highlight the need for change across all levels of service delivery, inclusive of individual professionals through to the systems and policies underpinning the structure and provision of services for parents and families. Further work is needed to explore how to implement and sustain effective change across multiple sectors to inform consistent, empathetic and therapeutic approaches to supporting parents, so children can grow and thrive within their own families and communities.

Summary

-

What is known about this topic:

- •

Adverse social and economic circumstances in childhood have lifelong impacts.

- •

Early support is necessary to ensure children thrive and reach their full potential.

- •

Seeking help is difficult, and parents face many barriers including stigma and blame.

-

What this paper adds:

- •

Parents seeking support encountered professionals who were disrespectful and unwilling to listen.

- •

Experiences included professionals who blamed parents for complex socioeconomic circumstances.

- •

Effective and sustainable change is needed for consistent and empathetic services across all sectors.

1. Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) refer to a wide range of potentially harmful circumstances during childhood inclusive of neglect, parental mental illness, substance use, financial stress, unstable housing and racism/discrimination [1, 2]. ACEs have a cumulative impact, meaning that more ACEs during childhood lead to a higher negative impact [1, 3]. Prevalence of ACEs varies due to different measures and local contexts, but around two thirds of young people internationally have experienced one or more ACEs [4]. Some population groups experience multiple adversities through compounding intergenerational cycles of disadvantage leading to lower educational attainment, poorer physical and mental health and/or increased contact with criminal justice systems [5–7]. Early identification, intervention and support for parents, families and communities experiencing adversity can enhance their capacity to provide environments where children can thrive and reach their full potential [8, 9].

Many countries have implemented strategies to promote early identification and support for families to mitigate the impacts of ACEs on children. However, when family and community circumstances place children at risk of harm, this may be labelled as child abuse and neglect. Child abuse and neglect is highly stigmatised, and many families subsequently avoid help-seeking and contact with supports when they perceive services as a pathway to child protection intervention [10]. This experience of child protection intervention is especially pertinent for First Nations Peoples who are survivors of the Stolen Generations (i.e., Australia and Canada) and continue to encounter racism, culturally unsafe services and overrepresentation within child protection [11, 12]. Reducing stigma and promoting help-seeking behaviours will require widespread changes in the systems, organisations and professionals who provide education, health and welfare services for children and families. However, current language of the policies and guidelines that underpin health and welfare practice emphasise protectionist responses, such as “child protection,” “keeping children safe” or “safeguarding,” which implicitly blame parents [13, 14]. When parents perceive judgement parents can feel pressured to present themselves in a positive light and are less likely to meaningfully engage in effective support [15–17]. Conversely, alternative language and discourses emphasising universal and early supports to keep families together are not yet well understood or universally shared amongst parents, communities and professionals [18].

Successful support for families is impacted by many factors, but therapeutic alliances such professionals’ interpersonal style, empathy, warmth and congruence accounts for around 30% of differences in client outcomes [19]. Professionals’ interpersonal style helps clients feel understood and accepted, thus building motivation and capacity achieve mutually agreed treatment goals [19]. Similarly, Loughlin et al. [20] found that clients’ most valued aspect of mental health early intervention was a positive relationship with at least one professional. Culturally safe, nonstigmatising communication from child and family professionals is core to ensuring all families feel comfortable when accessing services and seeking support. In doing so, families and communities are supported to provide safe and enriching environments where their children are enabled to grow and thrive. However, professionals’ therapeutic work with children and families is consciously and unconsciously influenced by the policies, systems and services that form the social context for their work [21, 22]. Policies, systems and services are underpinned by protectionist and parent blaming narratives, meaning professionals’ lived realities often reflect highly bureaucratised and risk-averse organisational contexts that impede genuine therapeutic relationships [23]. At the frontline, this means mainstream parent-blaming, risk-averse narratives may be lived out through language, communication and interactions with parents and families. Consequently, this review aimed to explore parents’ experiences of interactions with health, welfare and educational professionals when accessing support for adversities that impact parental capacity and children’s health, development or wellbeing in the early years (0–5 years). In doing so, we can identify elements of professionals’ interactions that parents viewed positively and negatively to inform future policy, practice, education and research.

2. Methods

A systematic review design of qualitative evidence was selected to explore the complexity of social phenomena and reflect the views of participants in the studies [24]. Qualitative evidence was pertinent to our review because we aimed to understand parents’ experiences of interactions with professionals when accessing support so we can make recommendations for education, policy and practice. Qualitative research enables an in-depth understanding of individual’s experiences that is not possible via quantitative statistical analysis [25]. The search protocol was registered with PROSPERO on 14th November 2022 (CRD42022370797).

2.1. Search Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were established in accordance with the study aims (Table 1). Parents were defined as any primary caregiver (social or biological) of a child. Foster or kinship carers who were legal caregivers of a child following statutory removal were excluded because their experiences are unique. Foster and kinship carers interact with supports before and/or after taking custody of children who were removed by child protection services, which is different from other parents.

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Qualitative (any design) and mixed method studies with a qualitative component |

|

To ensure a consistent understanding of parental adversities across the research team, we developed list of adversities (Table 2) from key international documents, namely, the World Health Organization [26], Centre for Disease Control’s Adverse Childhood Experiences [27], Australia’s Safe and Supported: National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children [28] and Public Health England’s No child left behind [29]. This list was comprehensive because no further potential parental adversities were identified during study screening and synthesis.

| Adversities that impact upon parental capacity |

|---|

|

3. Search Outcomes

A search was conducted in Medline, PsycINFO (via Ovid SP), Web of Science Core Collection (via ISI Web of Science), Social sciences abstract-(via ProQuest), Scopus and EmCare in November 2022 and repeated in July 2023. In addition, the reference list of included full texts was searched for any further relevant studies. No date limits or language limits were applied. A preliminary search was conducted in Medline (Ovid) to identify relevant articles, keywords and scope which guided development of a comprehensive search strategy (Supporting File 1). Search terms included combinations of all variations of the following words: “experience,” “attitude,” “perception,” “satisfaction,” “parent,” “father,” “mother,” “child,” “infant,” “baby,” “healthcare,” “child protection,” “child welfare,” “preschool,” “childcare,” “interaction,” “communication” and “relationship.” Articles retrieved from the Medline search were checked for inclusion of key publications, and the search was adapted for other databases by a research librarian.

3.1. Study Selection

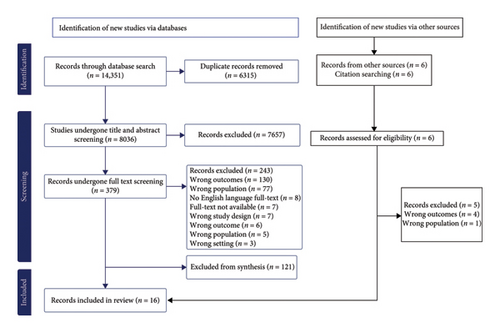

Next, citations were collated in Endnote and uploaded into Covidence where 6315 duplicates were removed. Independent title and abstract screening was undertaken by two authors and disagreements resolved through discussion. Next, 388 full texts were retrieved, imported into Covidence and assessed against the inclusion criteria. Full-text screening identified that many (n = 136) studies met the inclusion criteria but were not directly applicable to the context of interest (Australia). Therefore, only 16 studies which were conducted in Australia were included in the review synthesis (Figure 1). Key differences included (1) health and social care structures and services, (2) educational preparation and roles of professionals and (3) health and social issues not relevant to the Australian population. Consequently, the authors synthesised only Australian studies to enable meaningful recommendations for policy and practice. Thus, 16 qualitative manuscripts were included, with a full summary of search and study inclusion represented in Figure 1 (PRISMA chart). One challenge experienced when implementing inclusion and exclusion criteria was inadequate reporting of children’s ages. The authorship team decided to include studies where children’s age was unclear if studies otherwise met eligibility criteria to ensure relevant findings were not missed. Only three studies clearly reported children’s ages, but in other studies (n = 7), the service context (postnatal) or study inclusion criteria meant it was apparent all children were under 5 years. In the remaining six studies, it was not possible to determine children’s ages.

3.1.1. Quality Assessment

Studies were assessed for quality using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research [30] and a summary is available in Supporting File 2. All studies demonstrated congruity between philosophical perspectives, research methodologies, research questions and methods. However, some studies (n = 2) [31, 32] did not provide clear details of their analysis and interpretation, and some studies (n = 5) [31, 33–36] mentioned ethical practices (e.g., informed consent and confidentiality) but did not explicitly state whether their research had ethical approval. Only two studies [13, 37] discussed researchers’ cultural or theoretical backgrounds, and just one study [13] discussed the influence of the researchers on the research. No studies were excluded based on methodological quality.

3.1.2. Data Synthesis

Included studies were imported into NVivo (Version 12) to facilitate content analysis of study findings relating to parents’ experiences. Analysis was guided by the three steps of content analysis: (1) reading and rereading through the manuscripts, (2) identifying meaning units and (3) reflecting on themes and subthemes [38, 39]. In Step 1, the lead researcher read and reread the manuscripts to become familiar with their overall content. Next, in Step 2, the same researcher identified key meaning units from parents’ experiences by iteratively coding and recoding the findings sections of the manuscripts. These key meaning units were shared and discussed with the research team regularly to clarify understanding and promote accurate representation of the data. Finally, in Step 3, the researcher reflected upon codes and worked iteratively across the manuscripts to condense and resynthesise codes into themes and subthemes. Trustworthiness was promoted by a second researcher reading and reviewing one third of the subthemes to check for clarity, duplication and accurate representation of the data. The second researcher agreed with most subthemes, with the remaining three subthemes collaboratively reorganised by these two researchers to enhance precision and reduce duplication across subthemes.

4. Findings

Sixteen studies from Australia included in this review and an overview is presented in Table 3. These studies of parents’ experiences accessing support for parental adversities came from primarily statutory child protection (n = 8) and also from targeted nurse home visiting (n = 3), compulsory parent support (n = 2), perinatal mental health (n = 2) and hospitalisation for terminal illness (n = 1). Parental adversities were not always comprehensively reported, but included parents were experiencing one or more of the following challenges: mental and physical health concerns, substance use, domestic and family violence, housing insecurity, experiences of trauma, discrimination, social isolation, financial hardship, disability and/or incarceration. Throughout the results and findings, we use the term “parent” to describe study participants irrespective of whether they were mothers, fathers, grandparents or other primary caregivers.

| Authors, date & title | Study aims | Methods | Service context and parent characteristics | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

To understand power dynamics that shape parents’ experiences of family inclusion in child protection services. |

|

Parents (n = 6) who experienced removal of a child by the child protection service. Parental adversities included domestic and family violence, housing insecurity, substance use and intergenerational trauma. |

|

|

To improve child protection services by listening to parents’ and grandparents’ experiences of child protection services and what needs to change. |

|

Parents and grandparents (n = 9) who had experiences with child protection services for their children or grandchildren. Details of parent/grandparent adversities not reported. |

|

|

To understand how changes in practice (nursing and parental) were accomplished and how participants experienced partnership-based approaches |

|

Mothers (n = 3) who had been involved in a partnership-based nurse home visiting program for mothers with post-natal depression. |

|

|

Critical ecological study aiming to identify and understand experiences of parents using formal support services and the service and worker characteristics parents valued. |

|

Parents (n = 6) who had been referred to an intensive family support service by child protection after being identified as “in crisis.” |

|

|

|

|

Parents (n = 40) who had recently been investigated by the child protection service. Details of parent adversity not reported. |

|

|

To explore young families’ participation in decision making in child welfare services. |

|

Parents (n = 11) who had experienced substantial child protection intervention, including temporary removal of a child by the child protection service. Adversities included homelessness, domestic and family violence, substance use and/or mental health. |

|

|

To explore women’s experiences of support and treatment for postnatal depression |

|

Women (n = 7) currently or recently experiencing postnatal depression. |

|

|

To explore how mothers living with severe mental illness experience mothering after removal of their children by child protection services |

|

Women (n = 8) with a mental illness (nonacute phase) and had experienced removal of a child by the child protection service. |

|

|

|

|

Aboriginal parents (n = 26) and carers (n = 19) who had direct experience with child protection. Parental adversities included discrimination, domestic violence, substance use and/or incarceration. |

|

|

To explore consumers’ experiences of the meaning and relevance of their compulsory participation in a tertiary level child and family centre following a notification of child abuse and/or neglect. |

|

Women (n = 7) who participated in structured group activities to develop parenting skills and promote emotional responsiveness to their children. Parental adversities included social isolation, financial insecurity, trauma and domestic and family violence. |

|

|

To report women’s experiences of the child protection system. |

|

Women (n = 6) who had experienced removal of a child by child protection services. Women’s adversities included mental health, domestic violence and housing instability. |

|

|

To explore how women interpret and experience specialist perinatal and infant mental health (PIMH) services. |

|

Women (n = 11) who were referred to and accessed PIMH services for mental health and/or psychosocial concerns. Specialist PIMH services offer multidisciplinary inpatient care from a team of nurses, psychologists, social workers and psychiatrists. |

|

|

To explore mothers’ perspectives of an intensive home visiting program in South Australia by exploring their experiences of participation in the program and their experiences of the program as empowering them to change |

|

Women (n = 8) who had participated in the family home visiting program, delivered by nurses for “at-risk” mothers until child reaches age 2 years. |

|

|

To explore perspectives of patients diagnosed with incurable end-stage cancer and their families of parenting-related supportive care and what factors facilitate and hinder optimal parenting supportive care? |

|

Parents (n = 8) with incurable end-stage cancer and their partners (n = 4) accessing noncurative treatment at a large metropolitan hospital. |

|

|

To generate knowledge focused on parents’ involvement with child protection services in these two Australian jurisdictions during pregnancy and with their newborn. |

|

Parents (n = 13) who were involved with child protection services pre- or postbirth and/or had an infant removed due to concerns about child abuse/neglect. Parental adversities included housing insecurity, disability, incarceration and domestic and family violence. |

|

|

To investigate women’s perceptions of the Maternal Early Childhood Sustained Home-visiting (MECSH) program and the impact it had, upon reflection when their child was aged 5 years. |

|

Mothers (n = 36) who received the MESCH intervention. MESCH is a home visiting program delivered by nurses for at risk mothers antenatally until child reaches 2 years. |

|

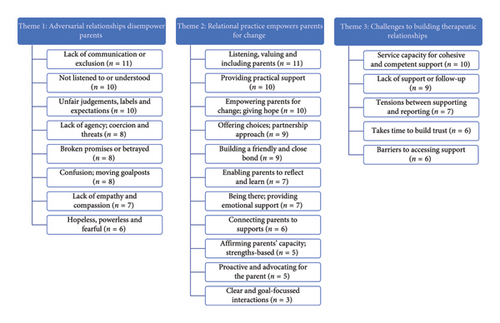

Studies’ publication dates ranged from 2002 to 2023, but no differences were found in findings from older studies compared with the more recent studies. Findings are presented within three key themes which are (1) adversarial relationship disempower parents, (2) relational practice empowers parents to make change and (3) challenges to building therapeutic relationships. The structure of themes and subthemes is represented visually in Figure 2 and are supported with representative excerpts from included studies in Supporting File 3.

4.1. Theme 1: Adversarial Relationships Disempower Parents

Theme 1 “Adversarial relationships disempower parents” described how parents’ perceptions of interactions with professionals as adversarial rather than supportive. Parents reported lack of empathy and often felt prejudged or blamed by professionals or situations where communication was inadequate or inappropriate.

At the core of parents’ experiences of adversarial relationships was a lack of empathy and compassion ( n = 7) [31, 32, 40–43, 45, 48], including where they were not listened to or understood ( n = 10). A lack of empathy included patronising attitudes [31, 41] and disregard for parents’ feelings [40, 43, 48]. Some professionals implemented supportive interventions but helpfulness was diminished if not paired with empathy. For example, one mother acknowledged helpful intent but explained: “You are looking for the human understanding, not the man or woman behind the seat that tells you what you have to do to feel better” [41]. Parents frequently felt professionals did not listen, or when they did “listen,” parents did not feel “heard.” For example, “I did not feel understood. They listened but were quite dismissive” [35]. Parents emphasised the value of listening to build understanding of “different stories” [40] for a nuanced picture of complex circumstances [13, 34, 35, 44].

Parents also experienced a lack of communication or exclusion ( n = 11) [13, 31, 32, 34–36, 40–44, 48]. Examples of lack of communication included failure to seek parental perspectives: “I am pretty much in the dark as to what is happening… there is not much communication” [35]. Difficulties also included parents feeling their input was rejected when professionals set boundaries on participation, “we were not allowed to ask her what school she’s at, if she’s progressing, where she’s got friends, whether she’s happy” [43]. At other times, communication was inadequate for parents’ needs, leading to confusion; moving goalposts (n = 8) [31, 32, 34, 36, 40–43, 48]. One parent needed ‘step by step’ explanations, saying “I could not see what they were trying to say in black and white. It was so confusing” [43]. At other times, parents experienced broken promises or betrayed (n = 8) [31, 32, 34, 35, 40, 43, 44, 48] after being misled: “They led us to believe we are keeping her [the baby] … [and later] handed me a piece of paper and said, we’re taking your baby” [48].

In addition to poor communication, some parents also experienced a lack of agency, coercion and threats (n = 8) [13, 31, 32, 34, 35, 43, 45] from professionals. Parents felt the lack of courtesy stemmed from unfair judgements, labels and expectations (n = 10) [13, 31, 32, 34–36, 40, 41, 48]: “they would not talk to us. They avoided us like we had herpes” [32]. At times, this meant parents felt they were seen as “part of the problem” [31]. First Nations families also experienced racism and discrimination: “we have different ways of looking after our children—they do not know how we act” [31]. Professionals’ negative judgements were not only unhelpful but also unfair because they did not acknowledge the complexity of parents’ circumstances. Many parents were impacted by past trauma [13, 31, 45, 46] and/or felt held responsible for their partner’s choice to use violence [36]. When parents did not meet expectations, they were scolded and/or coerced into “appropriate” behaviour which they had little power to challenge [13, 31, 32, 34, 35, 43, 45].

In summary, parents experiencing adversity often encountered poor communication and lack of respect from professionals. Consequently, instead of feeling supported to respond to challenges impacting parenting, parents felt ignored, blamed and without effective support.

4.2. Theme 2: Relational Practice Empowers Parents for Change

This theme reports positive relationships with professionals which helped parents feel validated and supported, introducing the possibility of change. All studies reported some examples of positive interactions with professionals. Key elements included the professionals’ interpersonal skills such as being there; providing emotional support (n = 7) [33, 35, 40, 44–46, 49] while listening, valuing and including parents (n = 11) [13, 34–36, 40, 41, 44–46, 49]. For example, one parent described the professionals as “just being supportive—emotional support, letting us know they are interested, knowing if we are having difficulty we can call them for help” [35]. Parents impacted by highly distressing circumstances needed a listening ear: “they let you express yourself and talk it all through … I was sitting here blubbering my eyes out, I was a mess and they care, I can tell them what problems I am having and they give me ideas of what to do” [44]. Professionals facilitated building a friendly and close bond (n = 9) [33–35, 44–46, 49]; this was especially valuable for parents with lower social capital: “Without them, I do not know what I would do, I have nobody else” [44]. Although relationships were friendly, some parents mentioned the importance of clear and goal-focussed interactions (n = 3) [33, 34, 36] clearly centred around parents’ health and wellbeing.

Other elements contributing to positive relationships included affirming parents’ capacity; strengths based (n = 5) [34–36, 44, 49], where professionals emphasised parents’ merits: “they praised me for the job I was doing” [35]. Professionals built parental agency by offering choices; partnership approach (n = 9) [13, 31, 33, 34, 36, 44, 46, 48], for example: “she would never tell me what to do” [33]. Given parents’ immediate social, financial and/or health needs, they also valued providing practical supports (n = 10) [13, 31, 34, 35, 37, 44, 46–49] and connecting parents to supports (n = 6) [31, 37, 41, 46–49]. Practical supports were tailored to parents’ circumstances to improve parental capacity: [Child protection] helped us out immensely, … they advocated on our behalf to get a house… gave us hampers, toys and tucker [31]. When professionals could not directly provide assistance, they linked parents with relevant services including parent support, playgroups, healthcare and counselling [37, 41, 49]. Helpfulness included being proactive and advocating for the parent (n = 5) [13, 32, 37, 45, 48] based on professionals’ anticipation of parental needs.

Through positive relationships with professionals, parents’ practical needs were met and their confidence and sense of agency were boosted. Parents were given opportunities to reflect on past experiences to consider ways to move forward. Thus, professionals were empowering parents for change, giving hope (n = 10) [13, 31, 33, 34, 36, 44–48] and enabling parents to reflect and learn (n = 7) [33, 34, 40, 43, 44, 46, 49]. Parents came from immensely difficult situations, but professionals’ support could build parents’ hopes of a better life: “she used to give me hope” [48]. In addition, parents appreciated how professionals enabled parents to reflect upon their assumptions and learn more positive ways of interacting, as outlined by one mother: “If I am calm, he [son] will be calmer … I have learnt it depends on how I talk to him too and he will answer back” [44]. Through positive interactions, professionals facilitated change for parents with flow-on benefits to parenting capacity.

This theme reported parents’ experiences of helpful, therapeutic interactions that made parents feel validated and supported to respond to challenges. For some parents, professionals’ supportive responses empowered parents to reflect and gain new perspectives, opening possibilities for change.

4.3. Theme 3: Challenges to Building Therapeutic Relationships

Although this review primarily explored elements of individual professional interactions, broader factors beyond individual professionals impacted parents’ experiences. Factors included service influences and parental characteristics. This final theme outlines parents’ key challenges to building therapeutic relationships as context for understanding parents’ experiences.

Parents reported barriers to accessing support (n = 6) [13, 32, 37, 41, 45, 49], including apprehension [13, 32, 37, 45], logistical challenges [13] or not knowing where to access help [41, 49]. Once parents did engage, they explained it takes time to build trust (n = 6) [13, 31, 36, 37, 45–48], especially because many parents had difficult histories [13, 31, 37, 45].

Although parents could establish trust with one professional, this did not necessarily carry through to other professionals or services. Parents highlighted service capacity for cohesive and competent support (n = 10) [13, 31, 34–36, 40, 43, 45, 48], such as helpful individuals [35, 45], but expressed frustrations about repeating their story [40] and poor coordination [13, 36]. At other times, parents’ experiences were clouded when service criteria did not fit parents’ complex needs [34, 36, 40, 48] or lead to unwanted child protection intervention [32, 43]. For example, one mother recognised her need for support but did not meet the criteria: “I asked for help for [daughter] because of her special needs and they pretty much said “Well, you’re not on a case, we can’t help you” [32].

Parents’ attempts to access support were often met with a lack of support or follow-up (n = 9) [31, 32, 34, 35, 37, 40, 41, 45, 48]. Sometimes, services had extensive waiting lists [41, 45], only provided short-term support [34] or did not follow-up [37]. Services parents engaged with were statutory child protection agencies (n = 8) or compulsory parenting services (n = 2), or other services where professionals were mandated reporters [50]. Consequently, tensions between supporting and reporting (n = 7) [31, 32, 34, 35, 43, 44, 48] arose when professionals prioritised child safety over parent support needs. Some parents disputed the validity of reports; other parents acknowledged professionals’ duty to respond to concerns of child harm: “I fully understand their duty of care…” [44]. Irrespective of perceived validity, parents expressed a desire for a greater transparency [34, 44].

In summary, parents’ interactions with professionals are influenced by individual professionals but also broader organisational and social factors. It is important to understand these factors to inform future service innovations and professional development.

5. Discussion

This systematic review of qualitative evidence explored parents’ experiences of interactions with professionals when accessing support for adversities impacting parental capacity and children’s health and wellbeing in Australia. Key findings highlighted how parents had a variety of experiences with professionals, ranging from positive and helpful through to disrespectful and dishonest. Given the significant impact of therapeutic relationships on client outcomes [19, 20], these findings will inform future policy, practice development and service innovation to better meet parents’ needs and enhance outcomes for children.

Although this review explored parents’ experiences of support for parental adversities from multiple different services and sectors, it was noteworthy that many (10 of 16) studies were in statutory child protection or compulsory parent support programmes. Child protection-focussed services have the primary aim of ensuring children’s health and safety, and supporting parental capacity is a mechanism to achieving children’s health and safety. Within this model of service provision, parents are positioned as a “problem” to be solved to improve children’s outcomes [13, 51]. The discourse of individual parents as “problem” stems from discriminatory discourses based on race, gender and class which are framed in medicolegal language of “risks” to children [52, 53]. Many parents with experiences of adversity have backgrounds of trauma, violence, marginalisation, discrimination and/or deprivation—which are not adequately acknowledged when abstracting individual parents from past experiences and broader interplay of socioeconomic factors [14, 18, 54]. Einboden [55] argued that these individualistic discourses allow professionals to separate themselves from the problem of child maltreatment by “othering” parents as “perpetrators,” whereby it is easier to legitimise treating parents disrespectfully. In doing so, children who were once “victims” in need of “protection,” grow up become parents with backgrounds of trauma, marginalisation and deprivation only reframed as perpetrators in a self-perpetuating system [56]. Consequently, there is a need to unearth destructive discourses of marginalised parents as abusers across every level from policy, education and service delivery for better support for parents experiencing adversity.

There are many well-established strategies and frameworks for engaging with families, such as “strengths-based” approaches, which emphasise parents’ strengths and resilience over parents “problems.” Growing evidence supports the positive impacts of strengths-based approaches where professionals partner with parents to identify strengths, support self-confidence and negotiate mutual goals [57]. However, not all professionals use effective evidence-informed strategies, instead using coercion and threats [58], shifting responsibility onto parents or avoiding sensitive topics [59, 60]. At times, ineffective strategies can be due to inadequate knowledge or perceptions that some aspects of care are outside their role [59, 61]. Furthermore, sometimes, professionals did not ask about experiences of adversity due to apprehensions about starting difficult and lengthy conversations that have no simple solution [62]. Professional knowledge and comfort with difficult conversations can be learnt over time through education and support [63]. If conversations about adversity are normalised across the spectrum of universal and targeted services, it can help destigmatise difficult conversations and reinforce the idea of child protection as a shared societal responsibility.

Parents within the included studies also reported experiences of challenging interactions with professionals that extended beyond the individual professionals. Challenges related to system organisation and service availability, such as poor service integration, long waiting lists, inflexibility and lack of assertive engagement [32, 34, 36, 41, 64]. However, parents also experienced hesitancy seeking and engaging with support until trusting relationships could be established; these relationships were easily damaged when professionals escalated concerns about children’s safety [31, 43, 44]. Although it was beyond the scope of this review to explore system impacts on parents’ interactions with professionals, the context of service provision must be considered when enhancing nonstigmatising support for parents experiencing adversity. For example, professionals’ work with families is often impacted by burnout, stigma of “dirty work” and organisational cultures of blame [65–67]. Furthermore, professionals can feel powerless to provide support to families in systems that are difficult to navigate, inadequately resourced and do not fit families’ needs [68]. Thus, if professionals are to work compassionately with families, it is essential they work in empathetic and supportive environments that enable effective working.

Importantly, interventions to support professionals to engage in therapeutic relationships with families must be consistent and coherent across services and sectors [69]. At present, services for families do not collaborate effectively for a multitude of reasons, and establishing shared ways of communicating with and about families across sectors will be core to enhancing parents’ ability to access nonstigmatising support [70]. At present, different professions each have unique roles and disciplinary perspectives for working with families that contribute to confusion and inhibit effective service coordination [71, 72]. There is a need for shared ways of relating across all professions working with children that also acknowledge the impacts of the social determinants of health and parents’ past experiences [54, 60, 73]. Further work is needed to establish key values, knowledge and skills required by all professionals in a system that compassionately prevents and responds to adversities.

5.1. Recommendations for Policy and Practice

This review has highlighted key challenges for Australian parents when accessing support for adversities that impact their parenting. The complexity of systems and service delivery means change will require sustained and collaborative action from all professionals and services responsible for children and families. For frontline professionals, this could include professional development opportunities to critically reflect upon their language and approaches for engaging with parents and building skills for difficult conversations. However, there are challenges around accessing suitable professional development because many current programs overemphasise risk-averse, child protective responses without incorporating skills for partnering with families experiencing adversity [74–76]. Consequently, building professionals’ capacity will require investment in development of professional education that teaches supportive, relational responses to parents to enable effective parenting [75, 77].

Professional knowledge and skills are important but must be underpinned by workplaces that enable relational practices. Organisations need strong leadership and commitment to implementing best-practice parental engagement, inclusive of clear guidelines, supervisory support and professional development for all staff. Specifically, this requires developing and enacting organisational cultures that promote partnerships with families in place of stringent adherence to risk-averse policies that marginalise parents and do not increase children’s safety [78, 79]. Examples of approaches that can promote engagement parents when embedded into services include strengths-based, trauma-informed, solutions-focussed and culturally safe practices [75, 77, 80]. Embedding these approaches into organisational practices requires a foundational culture of reflection and learning so professionals are not punished for unforeseeable poor outcomes for parents or children [79]. More broadly, best-practice strategies for engaging with parents must be consistent across services and sectors to inform shared approaches to parental support [81].

Furthermore, policy change should be founded upon a public health approach focussing on whole-of-population prevention and early support so fewer children require statutory child protection intervention [82]. In doing so, this public health lens can inform an Australia-wide service and sector orientation to explicitly acknowledge the complex interplay of current and historical socioeconomic conditions on families and reject narratives of individual blame [74]. Changes at all levels must to be guided by lived experiences of parents to ensure we effectively reduce experiences of stigma and blame that hinder help seeking and perpetuate cycles of marginalisation [83]. Further research is needed to identify effective intersectoral approaches to implement sustained change by all professionals, organisations and sectors working with families.

5.2. Limitations

This review has several limitations. First, the included studies do not represent the full range of sectors and services where parents may access support from health and social care professionals. Studies were primarily from statutory child protection services or compulsory parent support (10 of 16), while the others were from specialised services for parents experiencing severe adversities (mental health and terminal illness). There was minimal representation of parents’ experiences interactions with professionals within universal services which are the first point of contact. Second, studies did not always explicitly report children’s age, which made strict application of exclusion and inclusion criteria difficult. Consequently, it is possible some study findings also represented parents seeking support when experiencing adversities later in their parenting journey, such as with school-aged or adolescent children, where needs are different. Finally, our review excluded studies where the focus was on parents’ experiences of interactions when accessing routine health care rather than for support for a parental adversity. Although outside the scope of our review, studies about parents accessing routine healthcare services whilst also experiencing adversity may have further insights into parents’ diverse experiences. Despite these limitations, our review makes important contributions to understanding how parents experience interactions with professionals when accessing support, specifically in the Australian health and social care context. Therefore, it will inform future practice, policy and service innovation to improve parents’ experiences with accessing support from professionals when experiencing adversity.

6. Conclusion

This systematic review of qualitative evidence highlighted how parents accessing support for adversities in their children’s early years had many nontherapeutic and unhelpful encounters with professionals. Although health and welfare services should by nature promote parents’ capacity to raise thriving children, parents frequently experienced professionals who were unwilling to listen or even disrespectful. Importantly, professionals often did not acknowledge the complexities of parents’ past lives and blamed parents for complex circumstances and intergenerational patterns of disadvantage and marginalisation. These findings highlight the need for change across all levels of service delivery, from individual professionals through to the systems and policies that underpin the structure and orientation of services for parents and families. Further work is needed to explore how to implement and sustain effective change across multiple sectors to inform consistent, empathetic and therapeutic approaches to supporting parents so children grow up healthy and thriving in their own families and communities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors

Acknowledgements

The authors have nothing to report.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Supporting files are also described in text at the applicable section.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article or its Supporting information.