Mapping Case Management Activities to Support Implementation and Fidelity of a Pediatric Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Program

Abstract

Background: Hospital-based violence intervention programs (HVIPs) provide community-based case management to victims of violence and address recovery across a range of needs, including safety, medical, mental health, legal, and basic needs. Describing and standardizing program practices are essential in supporting victim service program replication and growth. Our aim was to explicate the discrete activities undertaken within a pediatric HVIP to support resolution of client needs. With this information, we developed visual goal maps, which can be used to enhance fidelity and delivery of evidence-informed HVIP case management services.

Methods: As part of a formative evaluation of a pediatric HVIP affiliated with a major urban Level I pediatric trauma center, we coded a retrospective sample of HVIP encounter notes (n = 2218) from a random sample of 67 former clients, stratified to ensure representation of a diversity of client demographics and needs. Program activities, resources, outputs, and outcomes were identified using a structured coding schema. Using a directed content analysis approach, we reviewed coded data to categorize discrete programmatic activities undertaken in support of clients’ recovery goals.

Results: We developed visual goal maps that illustrate common and exemplar activities HVIP case managers complete as they support clients in addressing recovery goals across 12 need domains. Maps illustrate common and exemplar activities HVIP staff complete as they support clients in addressing recovery goals across 12 need domains. Organizing the activities is used to achieve goals within need domains differentiated between case management services (e.g., obtain insurance information) and measurable recovery goals (e.g., provide mental health therapy).

Conclusions: These maps provide a user-friendly visualization to inform case management services to support client recovery. Within victim service programs, the maps may be useful tools to enhance training, guide care planning, support supervision, standardize program services, and ensure implementation fidelity.

1. Introduction

Rates of violent injury in the pediatric (age ≤ 18 years) population, including injuries from both penetrating and nonpenetrating mechanisms, have increased in the years following the COVID-19 pandemic [1–3]. Intentionally being stuck by or against (e.g., blunt trauma) remains the highest cause of all nonfatal, violence-related emergency department (ED) visits for pediatric patients (ages 5–18 years), resulting in nearly 170,000 ED visits in 2022 [4]. An urgent need exists to address recovery of children and adolescents from intentional violence, regardless of the injury mechanism. Hospital-based violence intervention programs (HVIPs) are a viable means of supporting the physical and emotional recovery of injured individuals and their families and reducing retaliation and recidivism [5, 6]. HVIPs typically provide community-focused and trauma-informed case management to individuals and their families following medical care of violence-related injuries, with the mission of supporting physical and psychosocial recovery, while addressing social determinants of health contributing to the risk of future violence [5]. HVIPs promote healing through wraparound and psychoeducational services, serving as a bridge for violently injured individuals and their families between hospital- and community-based resources. While adult-focused HVIPs largely support victims of firearm violence, in the pediatric setting, HVIPs and other hospital-based services commonly provide care to pediatric patients injured through a broader variety of mechanisms, including assault and blunt traumas [7]. As HVIPs gain popularity as a means to infuse a public health approach into violence prevention, their establishment within trauma centers continues to surge, including greater expansion into pediatric healthcare settings [8–11].

Existing studies of HVIPs demonstrate cross-program similarities regarding service domains and needs addressed, which are commonly related to mental health, employment, and education, among other social determinants of health-related needs [6, 12–14]. However, limited specifications presently exist regarding the activities programs undertake to assist clients in resolving these commonly identified recovery needs. This limits our ability to standardize and replicate the HVIP model, be good financial stewards of resources for prevention, and evaluate programmatic fidelity and impact, particularly across different programs and settings [15, 16]. With the expansion of HVIPs nationally, the need for tools to support consistent and replicable program implementation is pressing as lack of intervention fidelity has long been identified as a key driver of inconsistent outcomes when programs are translated beyond the research context [15, 17, 18]. Further, such tools will be valuable in assisting HVIP programs with achieving and implementing programs in alignment with the recently released Health Alliance for Violence Intervention (HAVI) Standards and Indicators [19]. A 2022 national survey of HVIPs found diversity in program models, staffing, funding types and levels, and extent of hospital buy-in [11]. This heterogeneity increases the likelihood of cross-program differences related to intensity, capacity, and service provision. As Smith et al. identified in their trial exportation of their HVIP program into another trauma center, “a blueprint of the intervention must be established” prior to successful program replication [15].

At present, however, in the varied and rapidly growing landscape of HVIPs, limited practice-based guidance exists to describe the day-to-day activities undertaken by program staff to address individual and family needs [16]. This contributes to what evaluators term the ‘black box’ phenomenon, wherein the mechanisms of interventions, their delivery, and for whom interventions are most effective are poorly explicated and understood [20]. Thus, there is a critical need for formative work in the HVIP field to develop practice-focused tools that can serve as a blueprint for implementation of an exemplar HVIP and support emerging programs as they consider potential resources, staffing, and partners required for replication of common HVIP activities.

To address a need for practice-based tools to support HVIP program fidelity and advance efforts to explicate the “black box” activities in which HVIPs engage, we conducted a formative evaluation of our pediatric HVIP, with the intention of establishing the resources, activities, outputs, and outcomes of our program. As part of those efforts, we aimed to identify the discrete activities carried out by HVIP case managers in partnership with clients and families to resolve client recovery goals. We built on our HVIP’s existing needs and goals directory, used for collaborative goal setting between case managers, clients, and families, to describe and illustrate the program activities associated with each recovery goal and inform care provision across 12 need domains. Within our pediatric HVIP, the goal maps created through this foundational work will be used to guide care delivery and monitor process outcomes and fidelity of evidence-informed care. For new and emerging HVIPs, these maps represent a valuable technical assistance resource to support staff training and enhance replicability of case management services. Furthermore, defining our program activities can support our elucidation of a theory of change for short-, medium-, and long-term outcomes in future work.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

We conducted a retrospective, qualitative analysis of 2218 encounter notes from a sample of 67 former clients of a single pediatric HVIP affiliated with an urban level I pediatric trauma center in the mid-Atlantic United States. Our pediatric HVIP supports patients aged 8–18 years who receive care in the ED or trauma unit for blunt or penetrating injuries resulting from nonfamilial, interpersonal violence. All participants resided within Philadelphia County at the time of their injury. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (protocol #19-017196). Because retrospective study activities involved no contact with identifiable subjects or identifiable data and were deemed minimal risk, the IRB granted the study team a waiver of consent, assent, and HIPAA authorization.

2.2. Data Source

We extracted encounter notes, documented by case managers after each encounter with or on behalf of a client, for a representative stratified random sample of 67 former clients from our program’s clinical data management system. The sample was selected from all HVIP clients with intake dates beginning in 2016 (reflective of our HVIP’s current structure) and discharge dates prior to March 14, 2020 (the initiation of COVID-related restrictions at our local institution). We stratified the sample by age at intake (< 12, 13–15, and 16–18 years), sex, and discharge status (completed case management vs. lost-to-follow-up or withdrew from services) to align with cumulative program characteristics. Age tertiles were established to reflect stages of adolescent development and the changing nature of caregiver engagement throughout adolescence. Our program enrolls roughly equal proportions of male and female clients, and thus, we selected our sample to reflect these equal gender proportions. The proportion of clients selected who completed case management versus discontinued care were based on the existing proportions of these dispositions at the time of our study. These efforts ensured accurate representation of the diversity of experiences of HVIP clients within our sample data.

After generating the random client sample, we reviewed a descriptive summary of the selected sample’s need domains to ensure that all potential existing case management need domains were represented in relative proportion to their frequencies program wide. These needs are initially identified in partnership with youth and families at the start of case management following a comprehensive biopsychosocial intake and continue to be identified throughout program participation as recovery needs evolve. All personally identifiable information (such as client and caregiver names, staff names, and dates) was removed from sampled encounter notes. The demographic and program completion characteristics of the final sample are provided in Table 1.

| Characteristic | n (%) or median (IQR) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 35 (52%) |

| Male | 32 (48%) |

| Racea | |

| Black or African American | 60 (90%) |

| Other racial identity or multiracial | 4 (6%) |

| White | 3 (4%) |

| Hispanic/latinxa | 3 (4%) |

| Mechanism of injury | |

| Blunt assault | 60 (90%) |

| Firearm | 5 (7%) |

| Stabbing | 2 (3%) |

| Age at HVIP intake (years) | 14 (12, 16) |

| Final program disposition | |

| Completed case management | 45 (67%) |

| Discontinued case management prior to goal resolution | 22 (33%) |

- aClients self-identified their race and ethnicity during program intakes.

2.3. Analysis

Using an inductive approach, we developed a coding scheme, wherein we generated codes to describe programmatic inputs, activities, and outputs through a line-by-line reading of a subset of the encounter notes. Two trained research staff coded encounter notes using the established coding scheme (see coding overview in Table 2) in an iterative process using Dedoose (Version 8.1), a cloud-based qualitative data management application. Initially, both coders independently coded encounter notes of four clients after which a satisfactory level of agreement was reached (Kappa > 0.80). A single coder coded encounter notes of remaining clients, with approximately 15% of remaining notes double-coded to check for coder drift and ensure continued high inter-rater reliability (average Kappa = 0.87).

| Root codes | Subcodes | Exemplar note(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Case management |

|

|

| Mental health interventions |

|

|

| Psychosocial support | N/A |

|

| Safety planning |

|

|

| Instrumental and tangible support |

|

|

| Program termination | N/A | “CM said she would come out to see (family) one more time and then close the case.” |

Using a directed content analysis approach, we reviewed coded data to categorize the discrete programmatic activities case managers perform to support clients within the program’s existing framework of 12 need domains and affiliated goals (Table 3). Case managers routinely use this framework as they partner with clients and their caregivers to identify recovery goals and to document client progress. A project team member (CM) developed visual maps for each need domain outlining specific activities case managers undertake to support each associated goal, as well as for general case management activities, which included activities common to multiple need domains broadly addressing: (1) advocacy and care coordination, (2) information provision, (3) emotional support and psychoeducation, and (4) skill building. These goal maps underwent an iterative member checking and revision process, through which HVIP case managers, case management supervisors (JT), evaluation staff (HMK), and program directors (RKM, LV) shared feedback to ensure accuracy of the interpretation and categorization of various activities, optimize formatting, and refine the level of included detail for optimal utility in program practice.

| Domain | Exemplar-affiliated goals |

|---|---|

| Basic needs |

|

| Education |

|

| Extracurricular |

|

| ID-license | • Assist the client/caregiver with procuring identification materials |

| Job |

|

| Legal |

|

| Medical |

|

| Mental health |

|

| Peer groups |

|

| Parenting support | • Refer the caregiver to parenting class |

| Public benefits |

|

| Safety |

|

3. Results

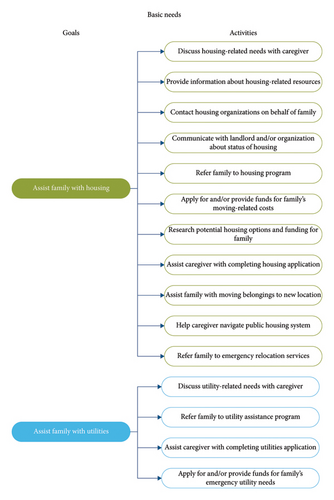

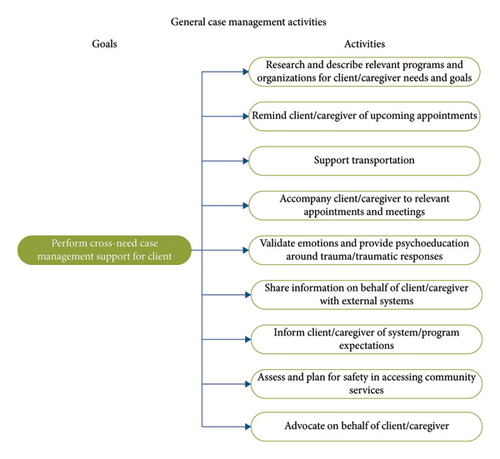

Based on review of the coded encounter notes, we identified case management activities aligning with 62 discrete goals across 12 need-specific domains. We additionally identified a series of activities reflective of general case management services, which were implemented and repeated across goals. While the need-specific domains (Table 3) were related to areas of physical and psychosocial well-being, the general case management domain captured cross-cutting activities documented across need domains, reflecting commonly documented case management activities used to address the diverse range of case management needs. With these categorized data, we created data-informed goal maps to explicate the discrete HVIP case management activities and their alignment with client goals within our HVIP’s pre-existing programmatic framework. We developed user-friendly goal maps to serve as visual summaries of the case management process (see examples in Figures 1 and 2 and https://violence.chop.edu/cvts-activity-maps for full collection of developed maps).

These maps exemplify the breadth of activities case managers and program staff perform, including both internal service provision (e.g., program-sponsored mental health therapy) and navigation within external systems to advocate with and on behalf of clients, connecting them to community-based resources. The maps summarize the activities case managers engage in to support a client in resolving specific goals, providing an outline of sequential actions staff undertake to guide clients throughout their recovery. The maps also provide an outline and trajectory of activities building upon one another (e.g., “Refer family to housing program” and “Assist family with moving furniture” are activities linked to the goal of “Assist family with housing needs”) in pursuit of supporting achievement of client’s goals.

4. Discussion

Informed by analysis of a stratified random sample of encounter notes from 67 clients participating in a well-established pediatric HVIP, we identified the activities commonly undertaken by program staff to support clients and their families in resolving postinjury recovery needs. We used these data to generate goal maps illustrating and describing the progressive actions program staff undertake to fulfill specific client and family goals. Looking forward, we believe that these evidence-based tools may serve multiple purposes for both new and existing HVIPs. First, these maps can be tools to standardize care within HVIPs, by supporting staff training in how to engage in goal-directed case management and enhancing replicability of case management practices across programs and staff. Further, we believe that these maps can be used prospectively to monitor program implementation fidelity, which is foundational to undertaking more rigorous evaluations of HVIPs, and aide in efforts to assess which activities may be related to specific outcomes.

Researchers have documented the heterogeneity of HVIPs in service offerings and program delivery models and identified need for greater model explication and standardization to advance the quality of implementation and evidence-informed program expansion [10, 11, 21, 22]. Our goal maps represent a novel effort toward this standardization through rigorously elucidating one model of pediatric-focused HVIP case management. Within programs, such maps may support intentional and aligned program delivery, ensuring the relevance of activities to client needs. In particular, they may provide a visual representation of program activities that case managers can use in discussions with clients to facilitate collaborative and transparent care planning and establish clear expectations for case management activities. These maps may help to democratize case management goal setting, by making clearer the activities a client or family can expect and creating a shared or common understanding of program support among both participants and program staff. From a supervisory perspective, maps may facilitate standardization of staff on-boarding and training and facilitate structured discussions about HVIP services between case managers and supervisors. In thinking toward continued dissemination of the HVIP model, these maps contribute a clear depiction of an established HVIP for emerging programs seeking to define and standardize their own models. The maps serve to advance shared understanding of the services provided and core activities carried out by program staff in support of clients’ recovery and offer a guiding tool for identifying resources to sustain a HVIP in addition to funding [23], including internal staffing and diverse community partnership needs. In the future, continued evaluation and development of these maps may provide helpful ways to further communicate program expectations and activities directly with clients, strengthening the shared understanding of program services, helping to ensure that activities are fully responsiveness to clients’ needs, and preparing clients to access resources in the future on their own.

We also believe our work to be an important and needed precursor to monitoring HVIP service fidelity. Fidelity monitoring is crucial for quality and consistency of care, enhanced programmatic and interventional outcomes, and successful program replication across fields, including mental health, substance abuse treatment, and case management [18, 24–30]. When used as a supportive practice, fidelity monitoring may also aid in staff retention [30]. Despite being widely recognized as a central factor to program quality, impact, and sustainability, fidelity monitoring tools remain underutilized in the case management and social work fields [31, 32]. The goal maps developed through this project provide a necessary prerequisite to developing data-informed fidelity monitoring tools for our local and other HVIPs.

Our methodical approach to identifying the key activities and outputs of our HVIP are additionally foundational to developing a clear theory of change for our and other HVIPs and establishing them as evidence-based practices. Illuminating the practices of HVIPs is crucial to meaningfully evaluating and successfully replicating these models of care [16]. HVIPs are diverse and complex, often offering individually tailored interventions to address myriad aspects of individual mental, physical, and social wellbeing. However, the mechanisms through which they promote recovery and resilience are poorly understood, limiting the ability to engage in rigorous impact and outcome evaluations [33]. Our maps define the activities through which our program model addresses specific client goals. These efforts are essential to supporting the future process and outcome evaluation. They create a shared knowledge of core case management activities and provide a framework for identifying outcomes which clients might most logically realize as a result of program services [20, 34]. While HVIP evaluations historically have centered reinjury as a primary outcome [35–38], our work may facilitate selection of specific measures to reflect nearer-term, salient program outcomes and contribute to more timely, interim program monitoring and evaluation [39, 40]. Further, this work may inform future thoughtful selection of program improvement activities to optimize program service delivery and realized outcomes [18, 20].

4.1. Limitations

The goal maps we produced have some limitations. Firstly, they were developed from the activities of a single pediatric HVIP that predominately provides longitudinal wraparound case management services for victims of community-based interpersonal violence and their families. As such, these maps cannot reflect the full spectrum of goals addressed and associated activities undertaken within all HVIP models, including peer-based models, brief hospital-based interventions, or those serving victims of other types of violence (e.g., intimate partner violence and trafficking). In particular, the pediatric nature of the surveyed program may limit the applicability of certain activities (such as those related to caregiver support or navigation of the education system) to adult HVIPs. However, the HVIP that informed our goal maps offers a wide range of internally and externally oriented services representative of those provided by other case management-based HVIPs, providing a guiding, if not all encompassing, framework. Our development process, framework, and template could also be extrapolated for use by the HVIP or victim service program with differing core services or client populations.

Our reliance on documented HVIP encounters as the primary source for generating case management activities is an additional limitation. This reliance may have led to the omission of activities due to a lack of documentation or over-emphasis on activities specific to the surveyed HVIP because of program- or locality-specific resources. Further, in defining HVIP goals and activities through existing documentation, our goal maps may not reflect the full spectrum of needed or desired services by clients and their families, particularly those which our HVIP may have been unable to address due to complex structural barriers or other resource constraints. However, the depth of our data, namely the size and diversity of our sample and the rigor of analysis, as well as continuous feedback from HVIP staff and leadership minimize this possibility. The rigor of our analysis is characterized by the coding of our entire sample with multiple coders and reviewers.

5. Conclusion and Future Directions

Through analysis of case manager documentation, we developed data-informed and practice-based HVIP goal maps elucidating the key activities case managers undertake to support violence-impacted clients and families in achieving their recovery goals. These goal maps offer a tangible tool for standardizing HVIP implementation and monitoring fidelity. As these maps are used within our program, future directions of this work include process evaluation to determine their feasibility of use for collaborative care planning with supervisors and clients, long-term acceptability among case managers, and their impact on HVIP service delivery. Our development methodology also describes a replicable process that can be adapted for other HVIP models or victim service programs who offer different or additional services. This formative work, specifically the elucidation of discrete programmatic activities, provides a new resource to facilitate dialogue regarding programmatic variation across HVIPs. It also may support thoughtful design of the cross-programmatic process and outcome evaluations.

Disclosure

The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication/program/exhibition are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Justice.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This project was supported by award no. 2019-V3-GX-0003, awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, the U.S. Department of Justice.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the HVIP clients who voluntarily participated in program services. They also thank Ami Deshpande, MSW, MPH, and Hannah Kim, BS, who supported qualitative coding of encounter notes.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.