A Missed Opportunity to Institutionalise Health Equity: A Qualitative Study on COVID-19 Vaccination for Socially Marginalised Groups in Emilia-Romagna (Italy)

Abstract

Health equity for people who have been socially marginalised (PSM) is still a major challenge for health systems, further exacerbated by the COVID-19 syndemic and vaccination campaign. Nevertheless, the relevance of these events may open windows of opportunity to reorient health policies from an equity perspective. Based on this premise, a qualitative study was conducted in the Emilia-Romagna region (Italy) during the COVID-19 vaccination campaign, with the aim to identify the policies and practices adopted by local health authorities in order to ensure vaccination of PSM. The study involved key informants working in dedicated outpatient clinics for PSM or in primary healthcare (PHC) departments. A short checklist was used to assess local practices, followed by semistructured interviews to further understand areas such as (a) strategies to promote accessibility/access, (b) approaches for vaccination delivery, (c) information system and data collection, (d) planning and governance and (f) opportunities and future perspectives. The findings show that the regional COVID-19 vaccination campaign was based on a tailored approach, promoting multimethod strategies to increase accessibility for PSM. Limitations of the study are the lack of direct experience of PSM and the lack of correlation between the identified strategies and vaccination rates. However, the study confirms the existence of systematic shortcomings and barriers in accessing PHC services, which contribute to the process of social marginalisation that is responsible for health inequalities among PSM. In this respect, the COVID-19 vaccination campaign ensured broader access to a specific intervention without addressing the structural and organisational determinants of health inequalities among PSM, thus representing a failed opportunity to institute health equity. Our findings suggest the need to strengthen political commitment and promote effective participatory health policies capable of identifying and overcoming structural barriers in order to achieve a structural change towards greater health equity.

1. Introduction

As decades of research have illustrated, health and disease are unevenly distributed within society, with ill health and premature mortality disproportionately affecting people who have been socially marginalised (PSM) [1]. These include people who have a migratory background, those experiencing homelessness, as well as groups and communities who are exposed to systematic and structural forms of discrimination [2, 3]. The resulting inequalities in health status depend on multiple factors, many of which are beyond the reach of healthcare services. However, health policies, practices, and particularly accessibility to primary healthcare (PHC) services can have a significant impact in mitigating (or reproducing) inequalities [4].

The Italian health legislation adopts a universalistic approach that guarantees healthcare coverage to all people living on the national territory, regardless of their country of origin and legal status. Nevertheless, different groups of people with migratory background have different entitlements; for instance, refugees and asylum seekers (RASs) holding a residence permit are enrolled in the Italian National Health Service (NHS) on an equal basis with Italian citizens. On the other hand, people who cannot register to the NHS (such as undocumented migrants) can only access emergency care and a range of essential secondary treatments, including prophylaxis of communicable diseases, through a specific health registration (STP: temporarily present foreigner), while access to PHC varies from region to region [5, 6]. This results in inequalities in the right to access healthcare based on different jurisdictions and relevant acceptance or refusal of asylum claims. Other factors may influence accessibility to health services, including bureaucratic, economic, cultural and linguistic barriers [7]. The presence of these barriers may vary in different regional and local contexts, as well as the mechanism of action, and for this reason, they need to be investigated in context-specific ways [5, 6].

In Emilia-Romagna, a region with a well-developed PHC network [8, 9] and with one of the highest rates of people with a migratory background in Italy [10], basic services for PSM facing barriers to healthcare are provided through dedicated outpatient clinics. These clinics are unevenly distributed throughout the region and can be either part of the NHS or established by civil society organisations (CSOs), with different degrees of public–private collaboration [11, 12]. Local evidence highlights the existence of health inequalities between the native population and people with migratory background, as well as between people who experience different levels of social marginalisation [13–16]. These inequalities have been partly linked to barriers in accessing health and social services, fragmentation of the PHC network and lack of policies to ensure equitable care for people with migratory background [11–13, 17].

In this scenario, the COVID-19 vaccination campaign, with its universalistic mandate, strongly oriented public services to develop strategies to increase accessibility and guarantee collective health [18]. Starting in December 2020, local health authorities (LHAs) in Emilia-Romagna invested a large amount of economic and human resources to guarantee the development of dedicated vaccination centres, pop-up clinics in urban areas and open days [19]. These efforts were complemented by a national measure introduced by the Ministry of Health in May 2021, which progressively made the COVID-19 immunisation certificate (Green Pass) mandatory to access bars, restaurants, workplaces, shelters and public offices.

Considering the COVID-19 vaccination campaign as a “natural experiment” to test the ability of health services to extend their reach towards greater health equity, this study analyses the strategies that were implemented in Emilia-Romagna to ensure access to COVID-19 vaccination for PSM, with a particular focus on people who face barriers in accessing or who are not enrolled in the NHS, such as refugees and asylum seekers, undocumented migrants and people experiencing homelessness. With reference to the relevant literature and existing guidelines, the study identifies the strengths and weaknesses of the adopted approaches and discusses the policy implications for equity oriented PHC services.

2. Materials and Methods

This study follows a qualitative approach and has a multiphasic and multicentred study design. The description of the study and the results follow the standards for reporting qualitative research (SPQR) guidelines for qualitative studies [20].

2.1. Study Design and Setting

The study took place in the Emilia-Romagna region between August 2021 and September 2022 (the second year of the COVID-19 vaccination campaign). It involved key informants, such as healthcare managers and professionals working in clinics for PSM, who had a role in the implementation of the COVID-19 vaccination campaign in the different provinces of the region. Inclusion criteria were based on purposive sampling, guided by previous work by the research team that had identified, for each province in the region, all key actors involved in the management of PSM clinics, whether public or private, or involved in local health authorities planning for PSM healthcare [11, 12]. Key informants were contacted by members of the research group by telephone to explain the aim of the study. Afterwards, the study protocol and consent collection form were sent by email.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Data collection took place in two subsequent phases. A rapid assessment (August–December 2021) was conducted through a short checklist (Supporting Information 1), which explored the operating procedures and the strengths and weaknesses of the strategies implemented by local health authorities and dedicated outpatient clinics to ensure access to COVID-19 vaccination for PSM. The checklist was emailed by the research group, completed by key informants and returned to the research team. The data collected through the checklists were reported on a digital grid and analysed through qualitative thematic analysis [21] based on key areas, identified from a scoping review of the existing guidelines on COVID-19 vaccination for the focus populations (Table 1) conducted during the study, through searching on the main national and international health institutional organisation websites.

| Strategies to promote vaccination accessibility |

|---|

| • Contrast vaccine misinformation and increase health literacy [22] |

| • Provide culturally and linguistically appropriate, accurate, timely and userfriendly information [23–25] |

| • Avoid stigmatising language [25] |

| • Involve community health workers, local, community and religious leaders [24, 26] |

| • Organise social media campaigns [24, 27] |

| Approaches for vaccination delivery |

| • Outreach measures: Pop-up or targeted clinics and vaccination buses at settings of convenience (faith settings, community venues, walk-in centres, drive-through facilities, homeless shelters, reception centres for migrants and asylum seekers, marketplaces and meal service sites) [22, 24, 27, 28]; |

| • Facilitate vaccination registration [29] |

| • Offer vaccine on a recurring basis in the same location [28] |

| • Overcome financial and potential administrative barriers: a) guarantee free and b) establish protocols that facilitate equitable access, especially for undocumented migrants’ access [28–30] |

| • Identify vaccination providers and staff who are known and trusted by historically marginalised communities to help build vaccination confidence [28] |

| Information systems, data collection and monitoring |

| • Gather local data on the behavioural and social drivers of vaccination [23] to address barriers and inform the design and evaluation of targeted strategies [22, 26] |

| • Reinforce information systems and data transmission [30] |

| Planning and governance |

| • Plan to use multiple and focussed strategies [28] |

| • Form intersectoral partnerships and involve diverse stakeholder groups in decision-making and planning processes [23, 24, 27, 28, 30] |

| • Strengthen collaboration across health departments [28] |

Subsequently (May–September 2022), a deeper and more comprehensive data collection phase was conducted through semistructured interviews with open-ended questions (Supporting Information 2), targeting the same key informants. The interviews aimed to ensure the validity of the data collected through the checklists and to explore in more detail local policies and practices, particularly in relation to (a) strategies to promote accessibility, (b) approaches for vaccination delivery, (c) information system and data collection activities, (d) planning and governance plans and (f) opportunities and prospects. Interviews were conducted in person or online, depending on logistical issues (distance and participants’ workload) and were conducted by at least two researchers, one conducting the interviews and the other taking field notes and assisting the interviewer. The interviews were conducted in Italian, recorded with the consent of the interviewee and then anonymised and transcribed verbatim. Given the nature of the study and according to the relevant Italian legislation (DM 26 January 2023 art.1 c.2 and EU Reg. n.536/2014 art.1 -2), ethical committee approval was not required.

The analysis of the interviews was conducted by four researchers from the team following the framework method using thematic analysis and a deductive–inductive approach [21, 31]. The transcripts were divided between the researchers and labelled according to the main thematic area of the interview guide (a–f) and emerged from the literature review. Then, for each area, a second step of analysis was carried out collectively to identify subthemes and to avoid possible personal misinterpretation by individual researchers. All analysis processes were conducted through/using a digital grid (Microsoft Word) and have been anonymised. No specific analysis software was used for the analysis. Data were grouped per label and organised in tables. Finally, the results were conceptualised following the perspective of comprehensive PHC (accessibility, continuity of care, community participation and governance) social determinants of health and biopolitics in health (governmentality and micropolitics), in order to identify possible insights for equity in healthcare policy (4, 32-34). To increase the trustworthiness and credibility of the data, the results were presented and discussed with the participants of the study during a meeting of the Regional Network of Medicine of Migration of Emilia-Romagna1 (Bologna, 31/01/2023).

3. Results

Data were collected in eight of the nine provinces of Emilia-Romagna (Table 2). Thirteen healthcare services were involved, of which seven were clinics run by CSOs, three were clinics run by NHS, and three were PHC departments of local health authorities. Of all the services identified, only the PHC department of the local health authorities of Rimini did not participate. Twenty one different healthcare professionals participated in the study, of which sixteen were doctors, three nurses, and two social workers. The checklists were collected in nine cities: eight provincial capitals (out of nine) and one smaller city and for all the 13 healthcare services. In three provinces (Bologna, Reggio-Emilia and Forli-Cesena) more than one checklist was collected per city, reflecting the number of clinics and key informants operating. Of the 13 services involved in the first assessment, only nine participated in the semistructured interviews, covering seven provinces of the region. In four services, no interviews were conducted because in three clinics run by CSOs (Faenza, Forli and Modena), the checklists highlighted that they had not been directly involved in the vaccination campaign, while in one PHC department (Bologna), the interview could not be arranged due to logistical issues. Of the nine interviews conducted, three were with professionals from NHS-run clinics, four were from CSO-run clinics and three were from the PHC department of local health authorities. Of these interviews, four were individual interviews with doctors and five were group interviews, with doctors, nurses and social workers who had filled in the checklist.

| Province/city | Involved services/checklist collected | Type of interview | Typology of personnel involved | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Piacenza | NHS-run clinic | Online/individual | 1 doctor |

| 2 | Reggio-Emilia | NHS-run clinic | Online/group | 1 doctor, 2 nurses, 2 social workers |

| CSO-run clinic | In person/individual | 1 doctor | ||

| 3 | Parma | NHS-run clinic | Online/group | 1 doctor, 1 nurse |

| 4 | Modena | CSO-run clinic | / | 1 doctor |

| 5 | Bologna | CSO-run clinic | In person/group | 2 doctors |

| CSO-run clinic | In person/group | 2 doctors | ||

| PHC department of local health authorities | / | 1 doctor | ||

| 6 | Ferrara | CSO-run clinic | In person/group | 2 doctors |

| 7 | Ravenna | PHC department of local health authorities | In person/individual | 1 doctor |

| Faenza (RA) | CSO-run clinic | / | 1 doctor | |

| 8 | Forli-Cesena | PHC department of local health authorities | Online/individual | 1 doctor |

| CSO-run clinic | / | 1 doctor | ||

| 9 | Rimini | / | / | / |

| Tot. | 13 | 9 | 21 | |

- Abbreviations: CSO, Civil Society Organization; NHS, National Health System; PHC, primary healthcare.

Findings are reported following the main area of the interview guide and integrated with the most representative translated quotes. The interview transcripts and data analysis are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

3.1. Strategies to Promote Vaccination Accessibility and Literacy

“Many people came specifically to ask about it …[…] for us the proactivity was face to face explaining what the vaccine is, what was in it, why they had to do it, what happened if they did it, and what happened if they didn’t do it…[…]here we were able to make a more in-depth cultural translation…”

(Doctor, NHS-run clinic)

“Many people would come here even if they could go to the vaccine hub…they would come to us so they could apply for the STP card”.

(Doctor, NHS-run clinic)

“Information meetings were organised for asylum seekers at the reception centre…[…]…They were usually always done in two languages— French and English”.

(Doctor, CSO-run clinic)

“…When the campaign lost strength we decided to close all the small spoke vaccination centres and to we tried to develop outreach initiatives…[…]…with the aim of diffusing information, enhance awareness, etc…in the municipalities which were more distant from urban centres, if there were public initiatives…at the market or at the village festival to intercept seasonal farm workers…” (Doctor, PHC Department of local health authorities)

“…what worked in my opinion was this qualitative, information survey distributed to 100 people…which allowed us with a few, but clear questions to assess what people know about COVID-19 vaccination, the existing barriers, the points of reference and so on…afterwards, we did a training with cultural mediators and community workers…”

(Doctor, NHS-run clinic)

“…there is no representative of Pakistanis here, because the Pakistani representatives represent Pakistanis who have health cards, which are absolutely repulsive to those who do not…”

(Doctor, NHS-run clinic)

“…here and at the Centres we had all the translated materials available…however, it seemed to me, that they were colourful little sheets of paper that they had in their hands…you could tell by the questions they asked you…I never see any of my patients read one of the 5000 brochures out here…not even the ones that were hanging…word of mouth and the spoken word in your face is much more valuable…”

(Doctor, NHS-run clinic)

“Yes, let’s say there wasn’t much proactivity on our part…We were caught up in 1,000 things, although there was still a debate, a certain level of sensitivity, let’s say, we didn’t structure such high participatory moments or involvement, at least in the districts where I work such a composite corporate strategy wasn’t there…”

(Doctor, PHC Department of local health authorities).

3.2. Approaches for Vaccination Delivery

“…I used to do the prevaccinal part and the medical history collection, so they would come…because obviously in the vaccination centre it was not possible to manage cultural mediation for all languages…So we would do this step and they would come with the documentation ready”.

(Doctor, NHS-run clinic)

“…We had set days and times, defined for people without a code who were not regular, because for the Hub it involved an extra workload…. they didn’t want free access…[…]…the mediator…It was one of the main problems…there was the administrative aspect that was a bit more complex than with the Italians and the very aspect of communication”.

(Doctor, clinics run by CSO)

“…. There was a large variety…I had a meeting…with the head of the CUP (Administrative office of local health authorities) with his assistants…they had said…[…]…that they would take care … .whether or not it was correct to give them the STP…[…]…there were very few STPs cards in a year…then two people retired who were particularly hostile to this kind of thing and there was a different stance in the practices…”

(Doctor, CSO-run clinic)

“…So, if the person had a regular visa and had residency, then he no longer has a regular visa, it lapses, but he continues to have residency, so he can’t have the STP card because formally he is not a temporarily present migrant, he results as a resident and so there is this administrative conflict. And unfortunately, this is something that you can’t solve because either he lapses residency, that is, he is delisted as a resident, and then he can have the STP card, but if he is a resident, he can’t have the STP card…”

(Doctor, CSO-run clinic)

“For the asylum seekers, we did dedicated sessions…it was crazy to organise…[…]…then whether they kept to the schedule, that’s another story…it was a moment of absolute chaos…”

(Doctor, NHS-run clinic)

“Efforts were made to create and form sessions with users from similar ethnic groups, who could precisely speak the same language. So we had sessions with a Chinese mediator rather than sessions with an English-speaking mediator, because there is also the possibility of activating mediators in addition to those in fixed presence…then we would actually collect the list of people to whom we had given information or who access with the request to be able to do the vaccination, after which we created precisely clinics with ad hoc mediator” (Doctor, NHS-run clinic)

“…There were outreach sessions and open days, where hard-to-reach populations were vaccinated…In canteens, we went with the mobile unit several times… when they would say “there are people who want to be vaccinated” we would agree and go there…. It was more difficult there…”

(Doctor, PHC Department of local health authorities)

3.3. Information Systems, Data Collection and Monitoring

“…The number of vaccinated people can be reconstructed however, it was not collected in a systematic way…not verification of adherence or completion of the cycle…in some facilities it was easier, for example, many worked on farms and so there was control…other populations are really hard to reach…”

(Doctor, PHC Department of local health authorities)

“…the other mistake, in my opinion […] was the lack of a regional informative system… we have vaccinated a lot of foreigners (undocumented) but there is no database, and no data come out…and that the thing that is missing the most, because it’s like not having an idea of what you do…we don’t have data for example on people who did not want to vaccinate” (Doctor, NHS-run clinic)

“As far as the CASs periodically I do survey round that you have to do again also to remind the managers to sensitise their guests but especially to see at what level of vaccination status they have within the facilities, so a periodic assessment…[…]…you have an initial situation, and from there you start to ask those who mediate with their guests about adherence to vaccination, or to sensitise them to vaccination or to understand why they don’t want to do it. There have also been those who have told us no. So active research is there, you do it through surveys…”

(Doctor, PHC Department of local health authorities)

“…The other big problem was that for people with STP, you couldn’t download the green pass even though they were vaccinated…[…]…that took an enormous amount of time because there was an error, and by vaccinating with a fake code, afterwards, you couldn’t download the green pass anymore, so you had to do it and do it again…[…]…. to give you an example, someone who is supposed to get married, who had done the vaccinations, could not go to the municipality to get married because it was a public place, in the public place you accessed it with green pass…he was at a stage where they were not issuing him a residence permit…[…]…people who could no longer access work and because they did not have green pass…”

(Doctor, clinic run by NHS).

3.4. Planning and Governance

“…it came a little bit from here…from the AUSL and from the public health department…there was not a good adherence from the migrant population, especially those from the reception centres…There was hesitancy to go to the public centres…fake news was going around…in certain groups, in certain nationalities…and so this idea of setting up a dedicated vaccination centre here emerged”.

(Doctor, CSO-run clinic)

“I would say from the local health authorities Direction. We saw that there was some difficulty…we brought our reports, after that it was the Health Directorate that made the arrangements by consulting directly with us”.

(Social worker, NHS-run clinic)

“The mayor himself, there is a council that is particularly sensitive with respect to these issues, and there is also the Mayor of the City, who was very present”

(Doctor, PHC Department of local health authorities).

“The dedicated task force was created in a natural way…then was the coordination group with the Health District and the primary health care Department, that put themselves there to collaborate to facilitate the whole pathway…”

(Doctor, PHC Department of local health authorities)

“The third sector, the dormitory, social and healthcare services…all those realities that revolve around my clinic, so they would propose the problem to me, and I would try to trade union them with the other offices, so I could figure out what relationships to put in place.”

(Doctor, NHS-run clinic)

“We went through an initial period when the path was not, let’s say, slim and smooth, it’s not so much now either, but back then it was much more nebulous and people risked waiting weeks or months, before they had in their hands a document that allowed them to be vaccinated and have all the rights of accessibility to public places…. I have to say, at least in my experience, it was difficult, in the sense that we lacked, at least I did, we lacked the information we needed…”

(Doctor, clinics run CSO)

“…My support over the years has been with XXX and YYY because we are similar. We have a similar approach…[…] we could phone each other to try to figure out what you do, what not to do, but informally …”.

(Doctor, NHS-run clinic)

3.5. Opportunities and Prospects

“Other needs, however, could be addressed in this way and, for example, for women…the problem of screening for cervix, for breast cancer…We could, however, make an active call for these people.”

(Doctor, clinics run by CSO)

“Meanwhile, one trivial but very true thing is that working alone doesn’t get you anywhere, in the sense that you have to form alliances…[…]…we did an assessment of all the low-threshold services in the territory, and we discovered things that we ignored until then…the goal is to apply everything in the prevention plan…there are quite a few ideas.”

(Doctor, PHC Department of local health authorities)

“…I am trying at all levels, including the regional one, to get our region to understand that every AUSL should have a reference point dedicated to migrants…I have photo that I would like to be able to send to someone who says to me…look at this thing…I’ve already seen it…I mean, it took me three years to make a diagnosis, because I didn’t know where to send it…”

(Doctor, NHS-run clinic)

“The most important lesson learned is the difficulty of continuity of care…[…]What indications can be structured in our area to ensure, if there is a need for continuity of care, but also different initiatives, how to be able to deliver these services to the hard-to-reach population in a context where social inequalities are increasing?”

(Doctor, PHC Department of local health authorities)

4. Discussion

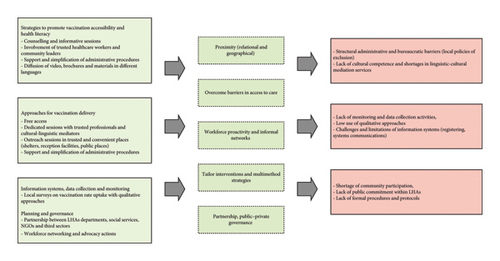

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first qualitative research describing the policies and practices that were implemented in Emilia-Romagna to guarantee access to COVID-19 vaccination for PSM. The data collected highlight the strengths and challenges of the strategies adopted by clinics and local health authorities and suggest considerations about promoting equity in vaccination and PHC services for PSM. Based on the available literature and existing guidelines, we argue that several of the adopted strategies were effective in increasing equity in access to vaccination and highlight shortcomings in their implementation. We also argue that more could be done to build on this experience in order to address structural barriers that limit the accessibility of the regional healthcare service for PSM. The following section will discuss the results of the study through the dialogue with key elements of equity-oriented policy in PHC: tailored interventions and multimethod strategies, community participation, data collection and monitoring, overcoming administrative and bureaucratic barriers, proximity and planning and governance (Figure 1).

4.1. Tailored Interventions and Multimethod Strategies

A first consideration is that, in all provinces, clinics and local health authorities developed a multimethod strategy to address the specific needs (and potential barriers) of different groups, in both vaccine promotion and delivery, with particular attention to vaccine hesitancy. Planning-tailored interventions is a central element, both in health promotion and in comprehensive PHC policies, and a recommended approach in different studies on equity in vaccination uptake, which suggest taking into account needs such as language, cultural differences and health literacy [35–37]. However, local assessment of vaccination attitudes and uptake rates, which is a recommended step to develop tailored interventions [22, 26, 38], has not been reported as a systematic practice, confirming the lack of structured data collection and monitoring activities on PSM at both the regional and local levels [39]. This is related to the limits of the regional healthcare information system in recording data on people who are not enlisted in the NHS, as well as to the lack of integration between the information system of clinics and the regional one. Limited experience and practice in qualitative research, which may help fill the information system gaps and deepen the understanding of local access patterns, also plays a role [11, 12, 40–44]. Based on these considerations, we highlight the existence of systematic issues and shortcomings in data collection and monitoring activities concerning PSM at the regional and local levels, which were not overcome during the COVID-19 vaccination campaign. These represent crucial barriers to achieving health equity, as they contribute to overshadowing the existence of certain population groups and their health needs, reducing the possibility to plan effective and tailored public health policies and perpetuating dynamics of institutional discrimination and structural exclusion [45–47].

4.2. Community Participation

Another key element for organising tailored and effective interventions in vaccination rollout for PSM is community participation [23, 24, 27, 28, 30, 48–53], which represents a central pillar of PHC policies and of equitable and rights-based approaches to health at the organisational, community and individual levels [33, 54]. Our evidence suggests that community participation and engagement by local health authorities have been absent or insufficient during the Emilia-Romagna COVID-19 vaccination campaign, at both the level of policies and of implemented practices. When spontaneous practices have emerged, such as information sharing on COVID-19 vaccination opportunities and access through word of mouth, they have been reported as being very relevant in supporting access. However, most of the interventions to promote and deliver COVID-19 vaccination were based on top-down approaches or on a process of consultation between clinics or local health authorities and other institutions (municipalities, third sector organisations and prefectures) not involving communities and PSM. These results are in line with previous works and confirm the limits and the challenge of the NHS in involving communities, especially if socially marginalised [12, 55, 56]. Lack of community participation represents a barrier to achieving health equity, not only because it influences the possibility of developing tailored policies and interventions, but also because it may contribute to generating mistrust and misconceptions towards healthcare services, increasing social exclusion and health inequalities [33, 53, 54, 57, 58]. The interpretation of community participation as a process of consultation corresponds to an idea of “inclusion” of situated viewpoints and ideas that aim to make interventions more effective and efficient, without, however, guaranteeing a space for negotiation between services and the community on priorities for allocation of resources and interventions and for action on the social determinants of one’s health [33, 53, 56–58]. Using this interpretation of participation means losing the transformative potential needed to address inequalities, overcome structural barriers and promote health equity.

4.3. Overcoming Administrative and Bureaucratic Barriers

Among the strategies adopted to address access barriers, actions to simplify administrative procedures have been reported in our research as effective in increasing vaccination uptake, a result also found in the literature [28–30, 52, 59]. Nevertheless, despite the national commitment to universal access and the efforts made by clinics and local health authorities, administrative barriers have been reported as one of the main challenges during the COVID-19 vaccination campaign as well as in accessing PHC services. This highlights their systematic and structural nature, pointing to the unresolved tension between the recognition of the right to health, as defined by international conventions, and national policies that regulate access to healthcare based on legal status [60]. To address this tension and interrupt the systematic exclusion from essential services of certain population groups, such requirements should be removed and access to the NHS should be universally guaranteed, as indicated by Article 32 of the Italian Constitution [45, 61]. In line with previous local research, our study also shows a persistent gap between the national policy framework and its implementation across local health authorities [11, 12, 17, 60]. In fact, access to healthcare at the local level is organised through bureaucratic procedures which work as “local policies of exclusion” [60] by requiring additional documents to access services, creating barriers that contribute to social exclusion and to poorer health outcomes. Identifying and addressing these barriers is therefore necessary to promote health equity at the PHC level [45]. In this respect, training of healthcare professionals and communication campaigns on how to overcome administrative problems and prevent discriminatory behaviours are recommended, together with monitoring of the policies’ implementation at the regional and local levels [33, 38, 39, 50, 52–67].

4.3.1. Proximity

Another adopted strategy was the practice of “proximity,” again something very central to any PHC approach. In our understanding, proximity includes geographical and relational dimensions and is tightly linked with concepts such as proactivity and outreach [68]. In a healthcare system that is still strongly based on a reactive rather than proactive approach, such as the Italian NHS, the efforts made by clinics to promote COVID-19 vaccination and organise vaccination sessions close to or inside different life contexts are to be highlighted. Several studies, confirmed by our data, emphasise the crucial importance of outreach activities in vaccine rollout to facilitate physical accessibility and contrast vaccine hesitancy [22–24, 27–30, 52, 69–72]. Evidence also suggests that outreaching helps to contrast mistrust towards the healthcare system, which is often related to physical distance from services, poor relationships with professionals and the feeling of being abandoned by the authorities [44, 70, 73, 74]. This is particularly true when trusted professionals are involved in promotional and delivery activities [28, 75–78], something which happened widely across the provinces involved in our research, thanks to the engagement of healthcare staff of clinics and social and other workers operating in reception centres, shelters and dormitories for PSM. However, our data also confirm what previous works have shown in terms of shortfalls of CLM and widespread lack of cultural competence across PHC services. Together with the presence of an adequate number of health professionals, CLM and cultural competence are crucial elements for implementing an effective proximity approach in a nondiscriminatory, respectful and welcoming way for PSM [23–25, 44, 52, 59, 74, 80]. Moreover, although it is possible to identify a proximity-oriented approach throughout the COVID-19 vaccination campaign for PSM, our study confirmed how these population groups still face several barriers in accessing healthcare and are often excluded from public PHC services. As detailed in the introduction, healthcare for PSM is guaranteed through clinics which, particularly when operated by CSOs, struggle to act as effective access points to the broader healthcare network, for lack of coordination with other public PHC services. This limits the benefits of their proximal role. Moreover, their uneven distribution and the absence of a coherent regional plan for ensuring equitable access to healthcare for all population groups result in geographic inequalities across the region [39, 45, 61]. Lastly, while confirming the crucial role that clinics play in ensuring accessibility to PHC for PSM, our study also leads to question their broader impact on the development of an equitable healthcare system. In fact, they can be seen as part of a delegation mechanism to ease the responsibility of the NHS towards the health needs of all population groups, something which may perpetuate, rather than contribute to addressing, the structural inequalities embedded in the national health policy [80].

4.3.2. Planning and Governance

Another aspect that deserves attention is related to the governance and planning of the COVID-19 vaccination campaign. While our results show that the COVID-19 vaccination campaign in Emilia-Romagna was a multistakeholder effort, involving clinics (both of the NHS and run by CSOs), local health authorities, municipalities and, in some cases, prefectures, they also highlight a reported lack of commitment and coordination (in the form of planning, protocols and procedures) by local and regional health authorities, which have the mandate to organise health interventions on their territory on an equitable basis for all population groups. This lack of structured public governance has been reported in Emilia-Romagna, as well as in other Italian regions, as a neglected area in PHC policies for PSM, particularly at the juncture between the local health authorities and clinics run by CSOs [12]. Consequently, in the context of the COVID-19 vaccination, as well as the more general PHC for PSM, the strategies and actions promoted to truly ensure access and equity have been advocated and acted upon mainly by clinics, social services and to the will and motivation of professionals, rather than on the implementation of structural policies [11, 12, 17]. The study also highlighted, in this respect, the role of formal networks (such as the Regional Network for Immigration and Health, GrIS or the health professionals’ network related to the ICARE European project), as well as informal ones activated by practitioners. These networks not only enabled the sharing of strategies and practices but also led to joint advocacy actions, at both local and regional levels, contributing to filling some of the planning and coordination gaps of the regional health authority. The role of formal and informal networks between health professionals in overcoming the structural barriers which are encountered by PSM and in driving institutional change in healthcare policies through bottom-up agency is well known, and the impact of advocacy efforts by GrIS and other CSOs in advancing health equity, at regional and national levels, has also been documented [60, 80–83]. However, relying on ad hoc networks (whether created through dedicated projects or promoted by third-sector organisations), to ensure core activities of the public healthcare system, poses the risk of perpetuating the structural failures of the NHS in fulfilling its mandate [60, 80, 81].

4.4. Implications for Equity-Oriented Health Interventions in PHC

- •

Promoting tailored strategies and personalized approaches: policies should prioritise multimethod and culturally sensitive interventions to address the specific needs and barriers of socially marginalised groups, adapting to different contexts, settings, resources and needs [35, 37, 38];

- •

Reinforcing data collection and informative system: PHC services should implement robust multimethod data collection and informative systems to better identify health inequities, inform targeted interventions and actively contrast and prevent institutional mechanisms of invisibilisation and discrimination [45–47];

- •

Promoting community engagement and participation: LHAs should improve community participation in health planning and delivering to contrast and prevent social exclusion, to promote social cohesion, rebuild trust and ensure that health interventions are planned and oriented with communities and marginalised people, avoiding mechanism of participation based on consultation and pursuing truly emancipatory participatory practices; [33, 53, 54, 57, 58];

- •

Facilitating healthcare accessibility: LHAs should actively adopt local policies and practices aimed to remove geographical, administrative, bureaucratic or economic barriers to accessing healthcare, including through the proximity of care delivery, the continuous training of practitioners, the proactive auditing of possible mechanisms of exclusion and discrimination on grounds of income, citizenship, residence or legal status [33, 38, 39, 50, 52–68].

- •

Reinforcing the governance of health equity: LHAs should strengthen the governance health equity system to ensure coordinated and equitable health care planning, ensure adequate resources and training of healthcare workers and plan the sustainability of interventions [83, 84];

4.5. Limitations

Our study presents some limitations. The COVID-19 vaccination campaign, as well as the COVID-19 syndemic, has been important and has been historical event in public health, which have interested and influenced different aspects of PHC services. In this regard, our study mainly focuses on clinics and specific activities of local health authorities for PSM, without looking at the overall rollout of the COVID-19 vaccination campaign. Moreover, since we used a qualitative approach based on interviews with healthcare professionals, our results neither speak to the lived experience of PSM,nor do they indicate whether the identified strategies have been effective in terms of uptake rates, something very challenging to assess, given the described limitations of the regional health information system.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study show that the COVID-19 vaccination campaign in Emilia-Romagna has been formally accessible for PSM with minor differences in the strategies adopted between groups and between local health authorities or clinics (whether run by the NHS or by CSOs) [11, 12]. The study also shows that these strategies were in line with what the literature recommends. In particular, the regional COVID-19 vaccination campaign was based on a tailored approach that allowed for the promotion of multimethod strategies, which made PHC services more accessible. On the other hand, the results highlight how, despite the efforts made by clinics and local health authorities, the COVID-19 vaccination campaign in Emilia-Romagna has not been without critical issues and barriers, which had earlier been reported also for PHC services [7, 11–13, 16, 17]. In particular, the study suggests that the presence of these barriers is systematic and contributes not only to reduced accessibility to healthcare services, including COVID-19 vaccination, but also to processes of social exclusion and marginalisation that are responsible for health inequalities among PSM. These shortcomings, as structural, precede and do not seem to have been affected by the policy promoted in the context of the COVID-19 vaccination campaign. In this regard, we argue that the COVID-19 vaccination campaign has been a missed opportunity to improve health equity. In fact, despite being backed by a universalistic thrust and supported with significant resources, the COVID-19 vaccination campaign ensured broader accessibility of a specific intervention, without interfering with the structural and organisational determinants of health inequalities among PSM (both at the level of healthcare accessibility and at the one of social exclusion and marginalisation). How health systems might be reformed or strengthened to improve health equity calls into question the matter of what we mean to be “equal” and “equity” within healthcare. From a social justice perspective, equity means positively discriminating in favour of those who start at a disadvantage. Applying this concept to health services means to “pay the equity premium” so that those in greater need than others can benefit from it [84]. To reach this goal and achieve (structural) change towards greater health equity, our findings suggest the need to strengthen the public and political commitment and to promote effective participatory health policies that are able to recognize and overcome structural barriers [32, 34, 79].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study. The costs of the publication are borne thanks to the University of Bologna.

Acknowledgements

The realisation of this work was possible thanks to the contribution of the following entities: Regional Network for Immigration and health, Emilia-Romagna; Ass. “Sokos”; Poliambulatorio “Biavati”; Ass. “Porta aperta”; Ass. “Querce di Mamre”; Ass. “Farsi prossimo”; Ass. “Salute e Solidarietà odv”; Center for Migration Medicine, AUSL of Piacenza; Center of Health of Migrants family, Azienda USL of Reggio-Emilia; Center for Migration Medicine, Azienda USL of Parma; Operative Unit of Migration and Vulnerability, Azienda USL of Bologna. In addition, parts of the manuscript were previously published as abstracts of the Virtual Conference on Migrant Health: Risk Communication and Protection against Discrimination during Health Crises (DOI: 10.5282/ubm/epub.10772) [85].

Endnotes

1The Emilia-Romagna Regional Network of Migration and Health (GrIS-ER) is a network of health and other professionals, who work in the field of migrant healthcare. It represents the regional branch of the Italian Society of Migration Medicine, and it aims to promote the rights and health of migrant people. To this end, it carries out practice exchange, dissemination and training, research and advocacy activities with local institutions.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data analysed during the current study are not publicly available due privacy reasons but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.