Family Needs in Parental Cancer: A Qualitative Analysis of Contextual Factors From the Perspective of Healthy Parents—Results From the Family-SCOUT Study

Abstract

Introduction: Parental cancer affects the whole family and can have negative impact on family as a system as well as on single family members. This multicentre, prospective, interventional and non-randomized family-SCOUT study aimed to implement a comprehensive psychosocial intervention to provide support for the family during and after the disease. The purpose of this study is to analyse the contextual factors that impact the subjective perceived effectiveness of family-scout support for families affected by parental cancer from the healthy parents’ perspective.

Methods: Semi-structured interviews with the healthy parent as a surrogate of family-SCOUT families from the intervention group were conducted. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and analysed using template analysis.

Results: Within two years, 23 interviews were conducted. Four themes were identified, highlighting contextual factors that indicate successful support for families: Ability to meet the support needs of families; cancer as a family disease—burdens in the context of the family system; coping strategies—how the individual family members deal with the situation and communication within the family.

Conclusion: Family-scouts can provide beneficial support to families affected by parental cancer, but individual time of the families, communication and stress factors need to be taken into consideration.

Trial Registration: Familien-SCOUT: NCT04186923

1. Introduction

Of the 15 million parents of underage children living in Germany, an estimated 37,000 are newly diagnosed with cancer each year, 20,000 of them are mothers [1]. Studies have shown that the negative psychological and physical effects of the illness can be enormous—not only for the sick parent (SP) but also for the healthy parent (HP) and their children [2–4]. These effects can involve high stress values, moderate to high depression and anxiety [2–4]. Furthermore, unmet psychosocial needs might lead to psychological problems in bereaved children and adolescents [2]. Psychological needs are, for example, to be able to have fun, to talk to someone at the own age who has been through a similar experience or to learn ways of coping with the added stress placed on the family. In a descriptive analysis of 278 bereaved children and 36 siblings, the highest proportion of unmet needs were ‘support from other young people’ and ‘time out and recreation’. Children’s and adolescents emotional functioning is furthermore associated with a functional family system. A high family cohesion, lower conflict and higher expressiveness in the family were associated with lower anxiety and depression among children and adolescents [5]. In addition, the well-being of children can be affected by a parents’ cancer in many ways and for a prolonged period. The parents are not only emotionally but also practically intensively involved in the disease management [6]. Some studies imply that offers of support should be designed for the entire family [7] and incorporate the family’s communicative resources as essential in accessing appropriate help [8]. A systematic review has identified psychosocial interventions and support services for families with parental cancer [9]. Inhestern and colleagues [9] included a total of 19 different interventions for families with minor children in their systematic review and identified barriers and facilitators for using psychosocial support. Family-centred interventions (n = 8) were covering a wide range of different settings (e.g., inpatient programs and ambulant care) and structures (e.g., weekly sessions vs. before and after death of the SP). Reported barriers for successful interventions were practical difficulties as time resources, disease characteristics or lack of collaboration with institutions, and reported facilitators were effective collaboration with institutions, facilitating emotional aspects, intervention characteristics (e.g., structure of the intervention and financial circumstances among others) and providing information. In Germany, there are currently no standardised services that children receive as soon as one of their parents develops cancer. Psycho-oncological counselling centres and cancer counselling centres can be the first points of contact, and there are also other (local) offers for counselling and psychological support for children [10].

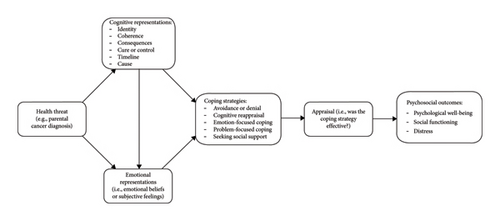

The complex psychosocial intervention family-SCOUT has been designed to improve care of the whole family, even after the death of the SP [11, 12]. The intervention provides a permanent, specially trained contact person (e.g., social worker), the so-called family-SCOUT, who provides information about all options available for organizational, emotional and communicative matters and facilitates access to existing support services [11]. Following the MRC Guidance for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions, the design of the intervention and the context are important to understand the mechanisms of action [13]. Context is defined as ‘any feature of the circumstances in which an intervention is conceived, developed, evaluated, and implemented’ [13]. Leventhal, Phillips, and Burns’s Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation is used as a theoretical framework for the contextual factors [14]. This model proposes a causal link between an individual’s belief about the illness, the coping strategies in response to the illness and the treatment [14]. Fletcher et al. [15] transferred the model for the illness cognition among adolescents who have a parent with cancer, see Figure 1 [15]. In response to an illness, an individual develops coping strategies which are consistent with their own representation of the illness. By identifying these beliefs or representations and their coping strategies, distress may be reduced and proposed by the authors, resulting in better psychological adjustment [15]. Furthermore, a positive coping style can have a positive impact on the psychological level of quality of life [17].

The aim of this study is to explore which family needs and contextual factors are associated with the subjective perceived effectiveness from the healthy parent’s perspective of the intervention. The results will be used in the intervention tailoring process to address specific needs of the family members and the family system.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

For the description of study design, data collection and data analysis, the COREQ guidelines were used, which can be found as Supporting Information [18]. The family-SCOUT study comprised a quasi-experimental, non-randomized, unblinded, prospective superiority control group design with two study arms (intervention and control) [11, 19]. In addition to quantitative data collection for summative evaluation, 50 semi-structured, partially longitudinal interviews were conducted in 32 families from intervention and control group for formative evaluation of the intervention. Due to the changes caused by the pandemic and the (temporary) stop of further data collection, the study team decided to conduct longitudinal interviews, which were not previously planned in the study protocol. In the second interview, the same interview guide was used as in the first interview; however, additional questions were asked about the situation during the pandemic and about the intensified communication within the families. The interview guideline can be found as Supporting Information, and the added questions for the second interview are underlined for better understanding. The interviews were conducted by two female members of the evaluation team, with a Master of Arts in Sociology and Social Research and with a Master of Science in Public Health. The researchers were trained in collection, management and analysis of qualitative data. No personal contact was established with the participants prior to the interviews. The central topics of the interview were the current situation in connection with the illness of a parent, the communication within the family and the need for support. Detailed information can be found in the study protocol [11]. The study was approved by the ethics committees of RWTH University Aachen (EK 195/18), University Hospital Bonn (267/18) and University Hospital Düsseldorf (2018-215-ProspDEuA). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The actively outreaching, family-centred, cross-sectoral intervention family-SCOUT was developed within the Comprehensive Cancer Center, Network Center of Integrated Oncology Aachen–Bonn–Cologne–Düsseldorf (CIOABCD) including four comprehensive cancer centers in the German Rhineland region [19]. The study was conducted at three participating cancer centers of excellence certified by the German Cancer Aid, namely, Aachen, Bonn, and Düsseldorf. The participants were recruited between January 2019 and December 2020 at the three study sites as well as at Bad Oeynhausen where only interview partners were recruited. These interview partners were added to address sampling diversity with including healthy parents from other regions in Germany. Inclusion criteria were an ICD-C diagnosis of at least one parent, custody of at least one minor child and sufficient German language skills. The exclusion criterion for participation was withdrawal of consent. The selection of interview families was made by purposive sampling. Criteria for selecting interviewees included gender, place of residence (urban/rural), number of children, perceived burden and educational background. The aim was to represent as heterogeneous a sample as possible. Information for the purposive sampling was obtained from the surveys of the summative evaluation.

As part of a pretest, three pilot interviews were conducted. No changes were made to the guide after pretesting. To determine the contextual factors for a successful intervention, the interviews of the intervention group were analysed. A total of 23 interviews in 16 intervention group families (seven longitudinal interviews) were conducted exclusively with the HP as a representative for the family. In order to keep the burdens within the families as low as possible, only the HP of the families was interviewed. The screening process already recorded how burdened the families are and the decision was made to keep the burden on the family as low as possible through the exclusive view of the HP and not interviewing children and/or the SP. Nine of the interviews were conducted face to face. Of these, eight took place at the families’ homes, and one interview took place in the hospital. The 14 following interviews took place by telephone. All interviews were recorded, transcribed and pseudonymized. Interviews were transcribed by an external transcription service. The transcripts were not presented to the participants.

2.2. Data Analysis

Template analysis, as a variant of thematic analysis, was carried out in this study [20–22]. The primary objective of template analysis is the development of a coding template derived from the examination of a segment of qualitative data, subsequently applied iteratively across the entire dataset with ongoing refinements [21, 22]. Noteworthy features of this approach encompass its coding structure’s adaptability, the formulation of a priori themes and the creation of an original template. The methodological progression comprised the following steps: (a) acquainting oneself with the data material; (b) preliminary coding of qualitative data, where evaluators identify and mark text segments deemed significant, and predefined a priori themes aid in organizing the data; (c) arranging themes into meaningful clusters and delineating their interrelationships, incorporating hierarchical connections that link narrower themes to broader ones; (d) defining and creating a preliminary coding template; (e) applying the preliminary template to the entire qualitative dataset, revising and reapplying it iteratively until a comprehensive understanding of themes and expressions is attained and (f) finalizing the coding template.

Following these methodological steps, the qualitative data within the context of the family-SCOUT project underwent analysis by five researchers within the evaluation team. This type of analysis was chosen because a pure content analysis of the data (as described in the study protocol) did not do justice to the depth and complexity of the data, and a more interpretive option was sought. Consistent engagement in weekly research workshops and meetings facilitated a continuous exchange of preliminary and initial findings, methodological challenges and procedures among the research team members. Challenges which encountered during the study were keeping the burden as low as possible for the HP and their families. The time and place of the interview were based on the wishes of HP, and interview breaks were offered if the burden became too high. Furthermore, due to the study design, families with higher levels of parental stress and more severe illnesses were thus more likely to be found in the IG. These circumstances needed to be addressed during data analysis, taking different stress and burden level into account. Due to the complexity of the data, no complete consensus was formed between the researchers.

3. Results

3.1. Sample

The average age of the 16 interviewed HP in the intervention group was 49 years (median 50 years and standard deviation of 10.2), with a range between 20 and 63 years. Nine of the interview partners were female, and seven were male. Detailed information of the sample can be found in Table 1. The interviews lasted an average of about 31 min. In total, five SP of the 16 families died before the first or between the first and second interview. The time between enrolment in the study and the interview date was between 22 and 268 days (on average 125.94) for the first interview. For the second interview, the time between study enrolment and interview was between 153 and 645 days (on average 419.43). The average time between the first and second interview was 257 days (median 261), with a standard deviation of 128. The shortest interval was 113 days, and the longest interval was 527 days.

| ID | Age of HP | Gender | Education | Net household income | Age first child | Age second child | Age third child |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 002 | 50–59 | Male | Intermediate secondary school education | Missing | 11–15 | ||

| 003 | 60–69 | Male | Lower secondary school qualification | 1.500€–2.000€ | 11–15 | 11–15 | |

| 004 | 30–39 | Female | Entrance certificate for a university of applied science | 3.000€–3.500€ | ≤ 5 | ||

| 005 | 50–59 | Female | Intermediate secondary school education | 2.000€–2.500€ | 6–10 | ||

| 014 | 50–59 | Male | University entrance certificate | 4.000€–4.500€ | 11–15 | ||

| 015 | 50–59 | Female | Intermediate secondary school education | 2.500€–3.000€ | 16–20 | ||

| 019 | 50–59 | Female | Entrance certificate for a university of applied science | 4.000€–4.500€ | 6–10 | 16–20 | |

| 022 | 40–49 | Female | Intermediate secondary school education | 2.500€–3.000€ | 11–15 | 16–20 | |

| 023 | 30–39 | Female | Intermediate secondary school education | 1.500€–2.000€ | ≤ 5 | ||

| 028 | 30–39 | Female | Missing | 2.000€–2.500€ | ≤ 5 | ||

| 029 | 40–49 | Male | Intermediate secondary school education | Missing | ≤ 5 | ||

| 030 | 40–49 | Male | Intermediate secondary school education | 3.500€–4.000€ | 11–15 | 16–20 | |

| 031 | 50–59 | Female | Entrance certificate for a university of applied science | 3.000€–3.500€ | 11–15 | 11–15 | 16–20 |

| 032 | < 20 | Male | Missing | Missing | Missing | ||

| 033 | 40–49 | Female | University entrance certificate | 3.000€–3.500€ | 6–10 | ||

| 034 | 40–49 | Male | University entrance certificate | 4.000€–4.500€ | 11–15 |

3.2. Contextual Factors

Overall, template analysis identified four central themes which are crucial for the subjective perceived effectiveness from the healthy parent’s perspective of the intervention that describe the contextual factors that impact the perceived effectiveness of family-scout support for families affected by parental cancer (Table 2).

| Contextual factors | Themes | Topics |

|---|---|---|

| Contextual factors of the interventions | Ability of family-scouts to meet the needs of families | Support areas of family-scouts |

| Contextual factors of families | Cancer as a family disease—burdens in the context of the family system | Burdens and family patterns |

| Coping strategies—how the individual family members deal with the situation | Different coping strategies and their impact as contextual factors | |

| Communication within the family | Communication and coping styles | |

3.3. Contextual Factors of the Intervention

3.3.1. Theme 1: Ability of Family-scouts to Meet the Needs of Families

The support areas of family-scouts are organization and bureaucracy, communication within the family and family relationships as well as emotional support and advice on dealing with the situation.

“She supported me, for example, at the very beginning with all the insurances. I had to deal so much with the health insurance, I had to make so many phone calls, I just couldn’t do it anymore because I had to look after my husband, I had to look after my child. And it took so much work away from me, with all the health insurance. And, yes, it worked. When (name f-scout) came, then it worked, it became calmer, I became calmer.” I023 (second interview)

3.4. Contextual Factors of Families

3.4.1. Theme 2: Cancer as a Family Disease—Burdens in the Context of the Family System

“Because the f-scout asked: “Here, do you need something? We could only say: “No, this is on the way, this is on the way, THIS is on the way”. And so, great that he asked, but couldn’t DO anything for us.” I014

“Well, my husband and I, we are not exactly the open people who wear our hearts on our sleeves. It has always been a bit difficult for us to really open up to someone we don’t know […].” I028

And, yes, we are very happy that the (name of F-scout) then came. Then she had talked to my husband like that. With me, when I was there. Then she also talked to my mother-in-law when she was there. And with (name of daughter). And of course, also talked to my son.” I019

“And then, at some point, I agreed with the (name of F-scout) that she/ Because my husband absolutely: “No, no, we don’t need it”. I also told him: “It’s not just about you, is it? It’s a family disease, it’s also about us.” I022

3.4.2. Theme 3: Coping Strategies—How the Individual Family Members Deal With the Situation

“But in the beginning, she also called very often of her own initiative, I think she saw right through me that I’m someone who says, “I need help”, but has a lot of difficulty in finally getting it started.” I015

‘Until I told my psychologist, yes, it’s a bit, bad like that, I tell the child psychologist about my mother everything, then I tell with my husband and the psychooncologist. And I also have to tell my son. I think that’s really bad. And then my husband said, “okay, maybe that is the better solution with the family-scout. And then it worked out.”’ I019

‘I: Why didn’t your husband want the family scout to support you?

B: He doesn’t deal with his illness. He doesn’t want to give the illness any more space than it already is. I then told him, “That’s all well and good, but it’s not just about you in that case.”’ I022

The handling of the children with the illness situation is a contextual factor for the intervention that is difficult to assess. The inner handling of the children was answered rather vaguely by the HPs and hardly linked to the intervention. In some cases, the HP reported that the children liked the family-scout and had conversations. This was mostly the case with younger children.

3.4.3. Theme 4: Communication Within the Family

‘Well, my husband and I are not exactly open-minded people who carry our hearts on our sleeves. It was always a bit difficult for us to really open up to someone you don’t know, but it was helpful because you know you have someone you can call, email, who cares, who comes over.’ I028

‘And my husband was also impressed because someone came to him and listened to him. And asked him what he needed, what he liked. And if he is well. And through her neutral views, she gave me some good advice, also in terms of my relationship with my in-laws.’ I019

In families where the coping styles are different, conflicts and alienation of the partners were reported. Communication is either conflict-ridden or hardly present. The intervention only failed in cases where extreme avoidance was present from both partners, making conversations about the topic almost impossible. In cases with opposite communication styles, the family-scout found an approach point with the more open parent to help the family.

Just like with coping style, communication with the children is difficult to evaluate and to link to the success of the intervention. In one case, where the parents had a different communication style, loyalty conflicts of the children were reported, who received contradictory information. Most parents are striving for age-appropriate and topic-appropriate communication and describe themselves as open to the children. The impression arose that the parents’ way of dealing with the illness was partly transferred to the children.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore which family needs and contextual factors are associated with the subjective perceived effectiveness of the family-SCOUT intervention from the healthy parent’s perspective. Semistructured interviews with the HP of families affected by parental cancer were evaluated using a template analysis. Four different themes of the contextual factors of the intervention were evaluated.

The various contextual factors interact individually in the families and led to differently pronounced help needs, which were reported by the HP. The family-scouts were perceived as an important reference person especially in organization and bureaucracy, communication within the family and family relationships and emotional support and counselling for dealing with the situation. They offered support tailored to the individual needs of the families, reducing barriers to help services and linking the different providers. The family-scout was perceived to be helpful in transitional situations such as diagnosis of the cancer disease and death of the SP, and the flexible response to family and individual needs through interventions directed to all members (HP, SP and children) was valued. Other service providers seemed to be limited to acute illness or treatment phase needs and to one person, usually the sick person, only. The intensity and degree of stress influence the individual need for help, with severe courses of disease associated with intensive secondary problems and increased help needs [6]. The HP of minors with a partner suffering from cancer is often burdened by everyday tasks, caring for the SP and financial problems due to the loss of income [23]. Whether the disease is the determining problem or interacts with further underlying problems has an impact on the need for help. Partners have a higher risk of mental health problems when treatment enters the palliative stage [24] besides offering psychological support and logistic assistance for their spouse [25].

A close relationship between communication style and coping strategy was observed. Those families who actively dealt with the situation showed a willingness to communicate and interact with others. Defensive attitude was usually associated with the desire not to be confronted with the topic in conversations. When couples had similar coping styles, conflicts seemed to be less reported by the HP. Conflicts and drastic alienation processes could result from different coping strategies. Pitceathly and Maguire showed that relationship problems increase the risk of mental health problems [24]. For success of intervention, an open attitude and communication style of one partner was sufficient [24]. Coyne et al. concluded that open and normalizing communication enable families to gain better access to resources, positive adaptation strategies and appropriate support [6]. Information about communication with children was sporadic and mostly superficial, so it should be given great importance in further investigations into effectiveness of the study and the intervention as open communication by parents helps support affected children [26]. Some parents are not aware of the importance of communicating with children about the illness [27]. Thastum et al. found emotional communication between parents and children can take place to limited extent, but children observe the parental emotional states and react with different coping strategies [26]. Therefore, further studies should investigate the perspective of children and the SP in more depth and should focus on children’s perceptions, burdens and coping strategies.

All four themes can be assigned to the coping strategies in the Leventhal’s Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation applied to parental cancer [15, 16]. Based on the model, the coping strategies identified are influenced by the cognitive and emotional representations of the family and individual members [15]. These representations are based on information provided by three domains: social interactions, personal experiences and cultural knowledge of the disease [15]. The contextual factors which are associated with the subjective perceived effectiveness from the healthy parent’s perspective of the family-SCOUT intervention can therefore be a result of the experiences and beliefs about the cancer disease individually of each family, before the intervention started. This needs to be taken into account from the family-SCOUT and other support interventions. Avoidance or denial, emotion- or problem-focused coping along with the form and the degree of seeking (social)support of the family-scout can be all build on that. With regard to the four themes, previous experiences and beliefs about the three domains need to be identified to relate the context factors individually to the family and Leventhal´s Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation applied to parental cancer in more detail.

4.1. Limitations and Strengths

A methodological and the main limitation of this study is that the HP was interviewed as a representative of the family. The effort not to burden the families even more than they are by the disease and the associated changes already led to the following limitations: From this representative perspective, blind spots were created in the present analysis, since the perspective of the entire family could not be adopted. The contextual factors which are present in the study are describing the subjective perceived effectiveness from the healthy parent’s perspective of the intervention. Methodologically, we were not able to pick up the family perspective through the interview, and it became clear within the interviews that it was very difficult for the HP to report the perspective vicariously.

The form of purposive sampling was used to recruit the interview partners, which may cause a possible selection bias. Another limitation is the nonstandardized timing of the interviews. Therefore, HPs with little experience of the intervention were not yet able to make reliable statements about their satisfaction with the intervention. In terms of content limitations, it cannot be conclusively determined in some cases whether the low emotional engagement with the situation conveyed in the interview reflects the family or the experience of the participants. Another limitation is the selection of the urban regions of Aachen and Bonn, where the intervention took place. It can be assumed that there was a good connection to other health services, which could have influenced the subjectively perceived effectiveness of the intervention. Rural regions with poor connections to university hospitals, medical care or cancer counselling services were not included.

The methodological strengths of this study include the fact that the subjective experiences of the HP could be collected accompanying the intervention and partly longitudinally. This allows for a comprehensive formative evaluation of the intervention and thus the possibility of adapting the intervention in healthcare reality bases on the presented results. The HP’s view of the contextual factors of the intervention (in addition to the limitation) is also a major strength of the study: Initial findings on the family’s perspective could be collected and thus provide indications of subjective perceived effectiveness of the intervention. Studies based on the findings of the family-SCOUT study are currently being developed and will take up the findings and limitations to get a more comprehensive understanding of families affected by parental cancer, by taking the perspectives and experiences of children, SP and HP in account.

5. Conclusion

A new family-centred, complex psychosocial intervention has been developed. It has proven to be feasible and helpful for families affected by parental cancer. Family-scouts can provide beneficial support, but individual time of the families, communication and stress factors need to be taken into consideration. Possible follow-up studies can deal with, among other things, the frequency of individual topics, subdivided according to subgroups such as gender, number of children or socioeconomic status. A specific analysis of changes over time in the longitudinal interviews also represents a need for further research. Since the present study does not take into account the views of the complete family or the views of the children, further qualitative research is needed with regard to a more holistic subjective perception.

Ethics Statement

Family-SCOUT has been approved by the leading Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the RWTH Aachen University on September 26, 2018 (EK195/18). Approval from all other involved local Ethical Committees was subsequently requested and obtained. Family-SCOUT will be conducted in accordance with legal and regulatory requirements, as well as the general principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki, Section 15 of the German Medical Association’s professional code of conduct ‘Berufsordnung für Ärzte, BOÄ’, and the applicable data protection law.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the German Innovation Fund of the Federal Joint Committee (Grant number: 01NVF17043).

Acknowledgements

We want to thank all participating families in F-SCOUT.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, L.H., upon reasonable request.