Use of Geriatric Assessments in Cancer Care: An Umbrella Review

Abstract

Background: Geriatric assessments (GAs) can guide treatment decision-making for older adults with cancer and identify those at risk of treatment complications. Given the number of systematic reviews conducted in the last 10 years, this umbrella review aimed to summarise and synthesise the evidence for (i) what constitutes a GA in cancer care, (ii) how GAs are conducted, and (iii) how implementation of GAs in cancer settings are reported.

Methods: PsycINFO, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane Library and Web of Science databases were searched and updated in September 2024. Systematic reviews with or without meta-analyses that (i) described the use or value of GA for older adults with cancer, or (ii) information related to GA implementation in cancer settings were included in this review. Quality of the reviews were assessed using the AMSTAR-2 tool, and results were descriptively summarised using a narrative synthesis.

Results: Twenty-nine reviews were included. A GA was commonly defined as a systematic, multidimensional evaluation of an older person. Recommendation for domains included within the GA differed across reviews. However, commonly reported domains and tools across reviews broadly mapped to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline recommendations. Fifteen reviews specified timing of GA; most reported assessments were performed prior to treatment and administered by a range of individuals including patient themselves, the multi-disciplinary team, individual nurse or cancer specialists or geriatrician-led consultation or assessments. Barriers and enablers to GA implementation were discussed in three reviews. Four reviews described GA feasibility, primarily reporting patient acceptability of self-administered or computer-based assessments.

Discussion: Heterogeneity across reviews in GA definition could impact on perceived feasibility of GA implementation. Standardisation of GA domains is required to facilitate evidence-based research and to guide integration of GA and GA-based interventions within cancer settings.

1. Introduction

Cancer management for older adults is often complex and challenging due to presence of multimorbidities or age-related vulnerabilities which can impact tolerance of cancer treatment [1, 2]. Furthermore, the under-representation of older adults in clinical trials [3] results in a lack of empirical evidence which makes treatment decision-making difficult for this population. As such, patients can be potentially overtreated or undertreated [4, 5]. To reduce the risk of suboptimal care and capture the presence of multimorbidities and / or age-related vulnerabilities, there is a need for a comprehensive assessment to inform decision-making. One such approach is the use of geriatric assessments (GAs).

Traditionally used in geriatric medicine, a comprehensive GA (CGA) is defined as a ‘multidimensional, interdisciplinary, diagnostic process to identify care needs, plan care and improve outcomes of frail older people’ [6]. Multiple domains incorporating physical health (nutrition, senses, multimorbidity), functional status, psychological health (cognition and mood) and socio-environmental parameters are assessed within a CGA [6, 7]. In the context of cancer, multiple international organisations such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [8], the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) [9, 10] and International Society of Geriatric Onoclogy [11] recommend conducting a GA to guide cancer treatment decisions and manage identified impairments. The use of a GA to inform treatment decision and management was also recommended in a recently published position statement led by the European Society of Medical Oncology and International Society of Geriatric Oncology Cancer in The Elderly Working group [12].

There is an increasing evidence demonstrating the value and effect of GA and GA-guided interventions for older adults with cancer [13–15] evidenced by the number of systematic reviews conducted in the last 10 years [16–20]. However, there has been little focus on implementation of GAs within routine cancer care [21]. Across reviews, lack of consensus on the domains, assessment tools, resourcing and time are often cited as barriers to implementation of GAs [22]. Consolidating review evidence will facilitate understanding of how GAs should be implemented as part of routine cancer care. As such, an umbrella review methodology was used as this allows for the synthesis of evidence from several reviews into one document to address specific questions [23]. An umbrella is informative when multiple systematic reviews have already been published on a specific research topic as this type of review systematically integrates, evaluates and aggregates the results of systematic reviews [24]. An aim of umbrella reviews is to present whether the evidence base for a topic is consistent or conflicting [24].

- i.

What constitutes a GA in cancer care?

- ii.

How is a GA conducted?

- iii.

How is implementation of GA in oncology settings reported? (i.e., the role, timing and implementation outcomes)

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

This review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42022338842). Results are reported according to the PRISMA guidelines [26].

2.2. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

PsycINFO, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane Library and Web of Science databases were searched. As Puts et al. (2012)’s review [16] was the first review synthesising results on the use of GAs in oncology, the search was limited to post-2012. An updated search was conducted September 2024. (see Supporting Table 1 search strategy).

Based on the aims of the umbrella review, we included systematic reviews with or without meta-analyses published in English that (i) described the use or value of GAs in cancer settings, or (ii) information related to implementation of GAs in cancer settings. The study population was older adults (age undefined) with any cancer and/or health professionals conducting GAs. Reviews not published in English and without a systematic methodology, commentaries, protocols and conference abstracts were excluded.

2.3. Study Selection Process

Title and abstract and full-text screening were conducted independently by two reviewers (SH and JS) using Covidence [27]. Disagreements were resolved through discussions.

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data extracted included: review aim(s), patient population (e.g. age, cancer type, cancer stage, treatment type), number of studies included, GA definition, methods for GA implementation and reported outcomes of the GA.

The data were descriptively synthesised and tabulated. Given that the GA domains and tools listed in the NCCN [8] recommendations have been grouped thematically, this allows for a systematic basis for collating the diversity of domains included across reviews. Therefore, the domains and tools reported in the reviews were mapped to the NCCN [8] recommendations.

2.5. Quality Assessment

The quality of included reviews were assessed (SH and JS) using the A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR-2) tool [28].

3. Results

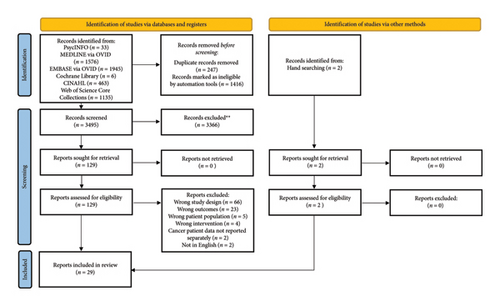

Database searches identified 3494 articles after duplicates were removed. Title and abstract screening resulted in 128 articles that were full-text reviewed. A total of 29 reviews were included. PRISMA flowchart is provided as Figure 1.

3.1. Review Characteristics

Of the 29 reviews [16–20, 29–52] identified, only two reviews [20, 49] specifically reported implementation outcomes. All other reviews focussed on the GA domains and outcomes. Most reviews (n = 20) [16–20, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 37, 38, 41, 43, 47–52] included all cancers/solid malignancies; however, three [30, 40, 44] were haematological specific, and seven reviews [33, 35, 36, 39, 42, 45, 46] reported on single-tumour populations. Three reviews [33, 35, 47] examined GA within surgical settings, and one in radiation oncology [43].

Across reviews, an older adult was defined as over 60 years in one review [47], over 65 (or reported a mean/median age of 65) in 15 reviews [16, 19, 20, 32–35, 37, 41, 43, 48–52] and mean age of 70 a single review [38]. Ten reviews [17, 18, 29–31, 39, 42, 44–46] did not impose an age limit and included studies with participants ranging from 18 to 99 years. Table 1 shows the Review Details.

| Reviews specifically reporting on GA implementation or integration in oncology settings (n = 2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First author (year) | Review context | Geriatric definition | GA definition | Aims | Key findings |

| Okoli (2021) [49] | Included study designs: Clinical studies, reviews, retrospective data analysis, clinical practice guidelines | Older adults: ≥ 65 years | Introduction: Reference to literature | To identify and map available evidence on integrating GAs into clinical oncological practice and ascertain which domains have been implemented | • Inconsistencies across domains that should be assessed within a GA. Comorbidity and functional status most consistently included |

| Number of included studies (articles): 38 (38) | Age of included study participants: NR | Inclusion criteria: not defined | • 27 articles reported on strategies for implementation. This varied and included self-administered paper based CGA, computer-based CGAs and brief versions of the CGA | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): Mixed/NR/NR |

|

||||

| Clinical setting: mixed (e.g., inpatient/outpatient, trial setting) | • Four papers reported on models for GA implementation. Models of GA implementation varied across papers. USA leads publications of models and integration of GA into oncology practice | ||||

| McKenzie (2021) [20] | Included study designs: mixed (e.g., surveys, qualitative studies, secondary data analysis, observational, cross-sectional, pilot studies) | Older adults: ≥ 65 years | Introduction: reference to literature | To review the literature on GA implementation in oncology settings, focussing on strategies that can be employed to overcome major implementation barriers | • Four programme theories were developed to address the common barriers to implementation of GA in oncology settings |

| Number of included studies (articles): 53 and 20 key stakeholder interviews | Age of included study participants: age NR (n = 16); ≥ 70 years (n = 14); ≥ 65 years (n = 10); ≥ 60 years (n = 4); ≥ 75 years (n = 4); median age 80 years (n = 2); ≥ 50 years (n = 1); mix 65 or 70 years (n = 1) | Inclusion criteria: not defined | • (1) ‘Leveraging on nonspecialists’ to address time barriers, (2) ‘creating a favourable health economics’ to address funding issues, (3) ‘establishing the use of GA in cancer care’ to address practicalities and (4) ‘managing limited resources’ | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): Mixed/mixed/NR | |||||

| Clinical setting: oncology (mixed) | |||||

| Reviews reporting on the use and or evidence of GA in oncology setting (n = 21) | |||||

| First author (year) | Review context | Geriatric definition | GA definition | Aims/research questions | Key findings |

| Puts (2012) [16] | Included study designs: prospective observational, cross-sectional observational, retrospective or chart reviews | Older adults: mean or median age ≥ 65 years | Introduction: not explicitly defined | (1) To provide an overview of all GA tools used in oncology settings, (2) to examine the feasibility and psychometric properties of the GA tools and (3) to systematically evaluate the impact of GA tools in predicting or modifying outcomes | • Common tools used to assess domains within a GA included Katz (ADL), Lawton (IADL), CCI or CIRS-G (comorbidity), MMSE (cognition), GDS (depression), MNA or BMI (nutrition), ECOG or Karnofsky (performance status), self-reported falls (falls risk) |

| Number of included studies (articles): 73 (83) | Age of included study participants: 65–99 years | Inclusion criteria: not defined | • GA generally took 10–45 min | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): Mixed/mixed/mixed | • Most of the 11 studies reporting on psychometric properties or diagnostic properties, examined diagnostic accuracy of short forms of the GA with a full GA. Short form GA generally had good diagnostic accuracy | ||||

| Clinical setting: mixed (e.g., hospital, inpatient/outpatient) | • Two of four studies reported GA impact on treatment decisions | ||||

| • Impairments on at least one GA domain were associated with treatment toxicity or complications (reported in 6/9 studies), mortality (in 8/16 studies), healthcare use in two studies | |||||

| • Impairments in ADL, comorbidity and poor mental health commonly associated with treatment toxicity and mortality | |||||

| Puts (2014) [19]–update to Puts (2012) | Included study designs: longitudinal observational, cross-sectional observational, retrospective | Older adults: mean or median age ≥ 65 years | Introduction: not specifically defined | (1) To provide an overview of all GA tools used in oncology settings, (2) to systematically evaluate their impact on the treatment decision-making process and their effectiveness in predicting outcomes from cancer and its treatment | • Common domains assessed within a GA included ADL, IADL, comorbidity, depression and cognitive function |

| Number of included studies (articles): 34 (35) | Age of included study participants: 55–99 years | Inclusion criteria: not defined | • Meta-analysis across six studies demonstrated GA-modified treatment decisions in 23.2% (weighted percent modification) | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): Mixed/mixed/mixed | • Heterogeneous results on predictive value of GA on treatment toxicity or complications in seven studies, and mortality in 11 studies | ||||

| Clinical setting: mixed (e.g., hospital, geriatric oncology clinic) | • Similar to previous review, impairment in ADL, performance status, depression and frailty associated with treatment complications or mortality | ||||

| • One study reported association between increasing frailty and increased cost of care | |||||

| Hamaker (2012) [31] | Included study designs: Cohort studies. | Older adults: no limit | Introduction: reference to published recommendation/position statement | • Median of five geriatric domains assessed per study | |

| Number of included studies (articles): 37 (51) | Age of included study participants: 18–99 years | Inclusion criteria: A GA was defined as an assessment using validated assessment tools composed of ≥ 2 of the following domains: cognitive function, mood/depression, nutritional status, ADL, IADL, comorbidity, polypharmacy, mobility/falls and frailty | To summarise all available evidence on the association between GA and oncological outcomes | • Frailty (in 9/10 studies), nutritional status (in all four studies), comorbidity assessed using CIRS-G (in 4/5 studies) predicted mortality | |

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): Mixed/mixed/mixed | • Frailty (in 2/3 studies) predicted chemotherapy toxicity | ||||

| Clinical setting: mixed (e.g., hospital, inpatient/outpatient | • Impairment in cognition (in 2/3 studies), comorbidity (in 2/3 studies), ADL impairment (in 2/3 studies) was associated with chemotherapy completion | ||||

| • Impairment in IADL (in 3/4 studies) was associated with peri-operative completion | |||||

| • No studies found reporting on association between GA and radiotherapy toxicity/completion | |||||

| Parks (2012) [36] | Included study designs: pilot study, prospective, retrospective, cross-sectional observational, retrospective review, multicentre study | Older adults: no limit | Introduction: reference to literature | To analyse current evidence regarding CGA in early breast cancer and highlight possible areas for further research | • Limited articles examined CGA with early breast cancer only |

| Number of included studies (articles): 9 (9) | Age of included study participants: > 70 (n = 4); ≥ 70 (n = 1); ≥ 71 (n = 1); ≥ 65 (n = 3) ^ | Inclusion criteria: not defined | • Quality of evidence is not strong enough to impact on immediate change in clinical practice | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): Early-stage breast cancer/mixed/mixed | • Common theme across studies was that CGA was used to identify comorbidities and factors that may influence/guide treatment decision or adjust treatment plans | ||||

| Clinical setting: mixed (e.g., hospital, inpatient/outpatient | |||||

| Ramjaun (2013) [32] | Included study designs: prospective cohort studies | Older adults: ≥ 65 years | Introduction: reference to cancer literature | To identify CGA domains that are most predictive of clinical outcomes in patients ≥ 65 years receiving treatment for nonmetastatic cancer | • One study reported association between comorbidity measured by CIRS-G and post-operative complications (OR = 5.62, 95% CI 2.18–14.50) |

| Number of included studies (articles): 9 (9) | Age of included study participants: NR | Inclusion criteria: defined as a CGA conducted before treatment which included functional status or autonomy, nutritional status, cognitive function, polypharmacy and the presence of geriatric syndromes (i.e., depression, osteoporosis, delirium) | • Treatment-related toxicity examined in three studies. Functional status (OR 1.71–2.47) and impaired hearing (OR = 1.67, 95% CI 1.04–2.69) associated with treatment-related toxicity | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): Mixed/NR/mixed | • At least one or more domains of CGA significantly predicted mortality (6/7 studies). Nutrition (HR 1.84–2.54), presence of geriatric syndromes, specifically depression measured by the GDS (HR 1.51–1.81) and impairment in functional status (HR 1.04–1.22) were strongly associated with mortality | ||||

| Clinical setting: mixed | |||||

| Versteeg (2014) [34] | Included study designs: prospective studies | Older adults: ≥ 65 years | Introduction: reference to guideline | To summarise the data on the predictive value of a GA on treatment toxicity, mortality and treatment decisions in elderly patients with solid cancer who are being treated with chemotherapy | • Six studies reported on predictive value of GA and treatment toxicity. Inconsistencies across studies in terms of domains that predicted toxicity. 49%–64% of older patients experience chemotherapy-related toxicity (at least grade 3) |

| Number of included studies (articles): 13 (13) | Age of included study participants: 65–99 years | Inclusion criteria: not defined | • Malnutrition, impairment in functional status and comorbidities, lower performance status and frailty associated with mortality. Malnutrition as consistent predictor of mortality across all studies | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): Mixed/NR/chemotherapy | • Across five studies, treatment modifications were made to 21%–53% of patients following GA. Impairment in functional status or malnutrition were common reasons for treatment modifications | ||||

| Clinical setting: mixed (e.g., medical oncology surgical, radiation oncology) | |||||

| Caillet (2014) [48] | Included study designs: prospective, cross-sectional, randomised trials | Older adults: ≥ 65 years | Introduction: referred to as a multidimensional assessment of patient’s health status using geriatric scales/tests to allow development of individualised geriatric interventions | To review evidence on the usefulness of CGA in assessing health problems, guiding decisions about cancer treatments, predicting outcomes and developing a coordinated programme of tailored geriatric interventions | • CGA identified a number of geriatric problems that could affect or interfere with treatment. |

| Number of included studies (articles): 40 (40)+ | Age of included study participants: 65–99 years | Inclusion criteria: defined as an assessment of at least five CGA domains (from nutrition, cognition, mood, functional status, mobility and falls, polypharmacy, comorbidities and social environment) | • 21%–49% of treatment decisions were influenced by a CGA. Five studies suggested function and nutritional status have the strongest effect | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): Mixed/NR/mixed | • Functional impairment, malnutrition and comorbidities were common predictors of mortality and chemotherapy-related toxicity | ||||

| Clinical setting: mixed (e.g., oncology, geriatric oncology clinics) | • Only three RCTs reported on effect of GA-based intervention with mixed results. Two reported benefits for older surgical patients, one RCT which reported on intervention plan for delirium did not report decreased occurrence of postoperative delirium | ||||

| Feng (2015) [47] | Included study designs: prospective studies | Older adults: ≥ 60 years | Introduction: referred to as an assessment of a patient’s physical, mental and social well-being | To assess which components of the CGA predict clinically relevant outcomes in geriatric surgical oncology | • Impairment in IADL, ADL, fatigue, cognition and frailty were associated with increased post-operative complications |

| Number of included studies (articles): 6 (6) | Age of included study participants: > 60 years | Inclusion criteria: any combination of CGA components were included, such as fitness assessment, mental and/or cognitive assessment, depression, nutrition, comorbidities, fatigue and/or laboratory values | • No CGA components predicted postoperative mortality (assessed in 4/6 studies) | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): solid tumours/NR/surgery | • Impairments in IADL and depression predicted discharge to a nonhome institution (assessed 2/6 studies) | ||||

| Clinical setting: surgical oncology | • Impairment in ADL (1 study), malnutrition (2 studies), inability to feed or shop for oneself (1 study) and polypharmacy (1 study) were associated with longer length of stay. In one study, frailty predicted postoperative readmission | ||||

| Schulkes (2016) [39] | Included study designs: cohort studies | Older adults: no limit | Introduction: reference to published recommendation/position statement | To assemble all available evidence on the relevance of the GA in treatment decisions, outcome prediction, and the prevalence of geriatric conditions in older patients with lung cancer | • Prevalence of geriatric conditions in older adults with lung cancer was high, median range 29% for cognitive impairment to 70% for impairment on IADL |

| Number of included studies (articles): 18 (23) | Age of included study participants: 73–81 years | Inclusion criteria: A GA was defined as an assessment using validated tools, composing ≥ 2 domains: cognitive function, mood/depression, nutritional status, ADL, IADL, polypharmacy, objectively measured physical capacity (e.g., hand grip strength, gait speed or balance tests), social support and frailty. Excluded medical history, comorbidity and PS as considered routine oncological workup | • Objective physical function and nutritional status were commonly associated with mortality (6/10 studies) | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): Lung/mixed/mixed | • Few significant associations found between GA domains and chemotherapy-related toxicity (noted across five studies) | ||||

| Clinical setting: NR | • Two studies looked at the correlation between treatment response and GA, however there was no significant association | ||||

| • Two of four studies found an association between GA and treatment completion | |||||

| • Treatment modification and implementation of nononcologic interventions were made based on a GA (across four studies) | |||||

| Molina-Garrido (2017) [42] | Included study designs: cohort studies | Older adults: | Introduction: A CGA was defined as a multidisciplinary and multidimensional evaluation of an elderly patient | To assemble all the evidence on the models of CGA, the main frailty screening tools which have been used in elderly patients with prostate cancer and their feasibility | • Geriatric impairments are prevalent in older adults with prostate cancer |

| Number of included studies (articles): 8 (8) | Age of included study participants: 65–93 years | Inclusion criteria: not defined | • No consensus on CGA model to be used for older adults with prostate cancer | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): prostate/NR/NR | • One study reported on association between basal information from CGA and early discontinuation, another article reported on association between frailty (based on CGA) and survival, treatment toxicity | ||||

| Clinical setting: NR | • Two studies reported that the VES-13 screening tool correctly identified frail patients (72.6%–90% accuracy) | ||||

| Van Deudekom (2016) [46] | Included study designs: longitudinal studies | Older adults: no limit | Introduction: not defined | To study the association of functional, cognitive impairment, social environment and frailty with adverse health outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer | • Impairment in functional status, depression symptoms and social isolation are prevalent in head and neck cancer patients |

| Number of included studies (articles): 31 (31) | Age of included study participants: mean age > 60 years& | Inclusion criteria: NR-only specified functional, cognitive impairment, social environment and frailty | • Most studies reported significant association in impairment in function, cognition, mood or social environment with adverse outcomes | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): head and Neck/mixed/mixed | • Cognitive function (reported in 2/31 studies), frailty and objectively measured physical function were not assessed for all head and neck cancer patients | ||||

| Clinical setting: mixed (e.g., medical oncology, radiation oncology) | |||||

| Van Deudekom (2018) [45] | Included study designs: longitudinal studies | Older adults: no limit | Introduction: not defined | To study the association of functional, cognitive impairment, social environment and frailty prior to any treatment with adverse health outcomes after follow-up) in patients diagnosed with oesophageal cancer | • Impairment in function, cognition, frailty were significant associated with adverse health outcomes (19/53 studies) |

| Number of included studies (articles): 19 (19) | Age of included study participants: mean age 55.23–79.5† | Inclusion criteria: NR-only specified functional, cognitive impairment, social environment and frailty | • Functional impairment or social environment significantly associated with adverse health outcomes (4/6 studies) | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): Oesophageal/mixed/mixed | • Objectively measured physical function, cognition (measured in 1/19 studies) and frailty were not measured in all oesophageal cancer patients | ||||

| Clinical setting: mixed | |||||

| Szumacher (2018) [43] | Included study designs: retrospective, cross-sectional and prospective trials | Older adults: mean or median age ≥ 65 years | Introduction: referred to as a ‘multidimensional, interdisciplinary evaluation, primarily used by geriatricians’ | (1) To provide an overview of all CGA instruments and geriatric screening tools that are used in the radiation oncology setting; (2) to examine the feasibility and psychometric properties of CGA and screening tools; and (3) to evaluate the impact of CGA instruments and geriatric screening tools on the radiation therapy treatment decision-making and their effectiveness in predicting cancer and treatment outcomes | • VES-13 and G8 were the most frequently used screening tools across five studies (used as standalone (n = 2); used to refer to CGA (n = 3) |

| Number of included studies (articles): 12 (14) | Age of included study participants: 61–95 years | Inclusion criteria: not defined | • A CGA was used in seven studies, a geriatrician-led assessment in four of the seven studies, and other studies patient self-administered | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): mixed/mixed/radiotherapy | • CGA required 80–120 min to complete (reported across three studies) | ||||

| Clinical setting: radiation oncology | • One study reported treatment modification based on CGA for five of six patients | ||||

| • There were a nonsignificant association between CGA impairment and treatment tolerance (in 6 studies) | |||||

| • Two studies reported correlation between mortality and lower G8 score and nutritional risk | |||||

| Hamaker (2013) [30] | Included study designs: cohort studies | Older adults: no limit | Introduction: reference to published recommendation/position statement | To determine relevance of GA for older patients with haematological malignancy and domains that are predictive of patient and cancer-related outcomes | • Prevalence of geriatric conditions was high despite good performance status |

| Number of included studies (articles): 15 (18) | Age of included study participants: 58–86 years | Inclusion criteria: A GA was defined as an assessment using validated tools, composed of ≥ 2 of the following domains: cognitive function, mood/depression, nutritional status, ADL, IADL, polypharmacy, objectively measured physical capacity (e.g., hand grip strength, gait speed/balance tests), social environment and frailty | • Predictive value of GA for mortality reported in 10 studies. Impairments in IADL (55%), cognition (83%), physical function (100%) and malnutrition (67%) were associated with mortality. Comorbidity, physical function and nutritional status retained significance in multivariate analysis | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): haematological/not applicable/mixed | Excluded medical history, comorbidity and PS as considered routine haematological workup | • One study found an association between comorbidity and chemotherapy-related nonhaematological toxicity | |||

| Clinical setting: haematological setting | • One study reported association between summarised outcome of GA and chemotherapy-related toxicity and response rates | ||||

| • Poor performance status, palliative treatment intent and renal dysfunction were associated with treatment noncompletion in multivariate analysis (reported in a single study) | |||||

| • Changes in GA during and after induction chemotherapy was reported in two studies | |||||

| Bruijnen (2019) [37] | Included study designs: Prospective, retrospective, unclear‡ | Older adults: ≥ 65 years | Introduction: reference to literature | To determine which domains of a GA predict patient- and treatment-related outcomes and therefore should be included within a GA | • At least one of the following domains: functional status, nutrition, cognition, mood, physical function, fatigue, social support and falls, predicted mortality, postoperative complications or treatment-related outcomes |

| Number of included studies (articles): 46 (46) | Age of included study participants: 65–99 years | Inclusion criteria: excluded comorbidity as GA domain as considered routine oncological workup, and frailty as usually defined as presence of one or more impairment on GA domain | • Physical function (5/8 studies) and nutritional status (13/23 studies) were common predictors of mortality. Similarly physical function (all four studies) and malnutrition (8/14) predicted chemotherapy-related outcomes (consisting of toxicity, dose modification, early withdrawal, functional decline) | ||

|

|

||||

| Salazar (2019) [40] | Included study designs: cohort studies (prospective and retrospective) | Older adults: not defined | Introduction: reference to published recommendation/position statement | To gather, evaluate and synthesise all available evidence on the effectiveness of GA and frailty scores in predicting mortality and drug toxicity in patients receiving treatment for multiple myeloma | • ADL, IADL, CCI, R-MCI, HCT CI and KFI were domains included in the GA across seven studies. Cognition, nutrition, polypharmacy and social support were not assessed in any of the included studies |

| Number of included studies (articles): 7 (7) | Age of included study participants: mean age 58–74 years | Inclusion criteria: GAs must include ≥ 2 of the following domains: nutrition, cognition, functional status, polypharmacy, social support and/or comorbidities. Frailty models based on a combination of age, comorbidities, performance/functional status and/or physical conditions or other published models of frailty were eligible | • Three studies reported association between GA and treatment-related toxicity | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): multiple myeloma/NR/mixed | • Predictive value of GA and mortality reported in all studies | ||||

| Clinical setting: myeloma setting | • Meta-analysis of three studies (3/7) reported increased risk of mortality for patients who had an activity of daily living score of less than or equal to 4. Based on frailty scores, increased risk of mortality for frail patients compared to fit patients | ||||

| Scheepers (2020) [44] | Included study designs: not specified | Older adults: no limit | Introduction: referred to as a systematic assessment of an older patient health status focussing on somatic, psychological, functional and social domains | To give an update of all currently available data on the association between geriatric impairments and haematologic cancer-related outcomes | • Polypharmacy (in a median of 51% of patients), risk of malnutrition (median 44%), IADL impairments (median 37%), impaired physical capacity (median 27%), ADL impairments (median 18%) symptoms of depression (median 25%; range, 10%–94%), and cognitive impairment (median 17%) were commonly reported geriatric impairments |

| Number of included studies (articles): 44 (54) | Age of included study participants: Me(di)an age 58–86 years | Inclusion criteria: an assessment composed of ≥ 2 of the following domains: cognitive function, mood, nutritional status, ADLs, IADLs, polypharmacy (≥ 5 drugs), objectively measured physical capacity (e.g., gait speed, hand grip strength/balance tests), social support and frailty (using screening tool or summarised GA). Excluded medical history, comorbidity and PS as considered routine haematological workup | • Frailty (defined by screening tool or summarising GA) was associated with mortality, treatment-related toxicity and noncompletion | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): haematological/not applicable/mixed | • 10 studies considered treatment-related toxicity as an outcome. Frailty associated with treatment-related toxicity in 4/6 studies | ||||

| Clinical setting:Haematological setting | • Association between geriatric impairment and treatment completion reported in 4/5 studies. Frailty was associated with higher risk of treatment non-completion | ||||

| • Six of seven studies reported association between geriatric impairment and healthcare use. Impaired physical capacity commonly associated with healthcare utilisation (reported in 4/6 studies) | |||||

| • Quality of life hardly assessed in included studies | |||||

| Xue (2018) [33] | Included study designs: cohort studies | Older adults: ≥ 65 years | Introduction: reference to cancer literature | To conduct a meta-analysis to identify the effectiveness of CGA for predicting postoperative complications in gastrointestinal cancer patients | • Comorbidity, polypharmacy, function, cognition, depression and nutritional status were evaluated in ≥ 4 studies |

| Number of included studies (articles): 6 (6) | Age of included study participants: mean age 64–81.5 years | Inclusion criteria: not defined | • Meta-analysis (6 studies) identified predictive value of comorbidity (measured by CCI), polypharmacy (≥ 5 drugs/day) and impairments ADL with 30-day postoperative major complications in gastrointestinal cancer patients | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): gastrointestinal/NR/surgery | • Polypharmacy, pain scale score > 0 and ≥ 10% weight loss independently related to 90-day postoperative major outcomes reported in single study | ||||

| Clinical setting: surgical oncology | |||||

| Lee (2022) [41] | Included study designs: clinical trials (randomised trials, post hoc prognostic studies, single-arm studies) | Older adults: at least one patient ≥ 65 years | Introduction: reference to published guidelines | To synthesise the literature on GA use in cancer clinical trials | • Across 63 studies, there were 74 reasons as to why a GA was used. The most common reasons were to determine association between impairments in GA domains and clinical trial outcomes (38%) |

| Number of included studies (articles): 63 (63) | Age of included study participants: me(di)an age 74–77 years for most studies (34/63, 54%) | Inclusion criteria: not defined§ | • GA mostly conducted prior to treatment initiation | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): mixed/NR/NR | • 258 GA domains assessed, physical status and comorbidities were commonly domains | ||||

| Clinical setting: cancer clinical trials | • Significant heterogeneity in tools used to assess GA domains | ||||

| • Most trials (32/63) that used a GA were a phase 2 clinical trial | |||||

| Szabat (2021) [35] | Included study designs: retrospective controlled clinical trial, prospective, retrospective cohort studies | Older adults: ≥ 65 years. | Introduction: reference to cancer literature | To summarise results of studies investigating individual domains of GAs and the GA among older patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery | • Common GA components include function (ADL, IADL), cognition (using MMSE), mood (using GDS), comorbidity (using CCI), polypharmacy (number of drugs) |

| Number of included studies (articles): 10 (10) | Age of included study participants: ≥ 70 years (n = 4); ≥ 75 years (n = 3); ≥ 65 years (n = 3) | Inclusion criteria: not defined | • Inconsistencies across individual domains that predicted postoperative complications. Reason for inconsistencies due to heterogeneity of included studies | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): mixed/NR/surgery | • Impairment in functional status was a reliable predictor for risk of postoperative complications | ||||

| Clinical setting: NR | • Authors confirmed effectiveness of cumulative GA in predicting postoperative complications following laparoscopic surgery | ||||

| Couderc (2019) [38] | Included study designs: prospective and retrospective observational studies, randomised clinical trials and nonrandomised interventional study | Older adults: mean age > 70 years | Introduction: reference to literature | To review the data available on the most frequently used tools to assess ADL, IADL in geriatric oncology setting and their predictive value on overall survival, toxicity, treatment feasibility/decisions, and postoperative complications | • The most commonly used tool to assess ADL was the Katz, and for IADL, the Lawton scale. The loss of ability to perform at least one activity on the Katz was used as the cut-off (i.e., categorise patient as dependent or independent), the same cut-off was used for the Lawton scale |

| Number of included studies (articles): 40 (40) | Age of included study participants: NR | Inclusion criteria: not defined | • Functional status predicted mortality in 11 of 22 studies, treatment feasibility in 2/5 studies, changes in treatment decisions for 2/3 studies and postoperative complications in 4/6 studies. Following a regression analysis, functional status was significantly associated with chemotoxicity in 2/7 studies | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): mixed/mixed/mixed | |||||

| Clinical setting: geriatric oncology | |||||

| Reviews reporting on the impact or efficacy of GAs (n = 7) | |||||

| First author (year) | Review context | Geriatric definition | GA definition | Aims/research questions | Key findings |

| Hamaker (2014) [17] | Included study designs: observational cohort studies | Older adults: no limit | Introduction: not defined | To summarise data on the effect of a geriatric evaluation (GE) on oncologic treatment decisions and implementation of non-oncologic interventions for older adults with cancer | • Frequently detected conditions were polypharmacy (median 67%), malnourishment (median 63%), functional impairments (IADL median 45%, ADL median 43%, mobility/falls median 33%), depressive symptoms median 34%, somatic comorbidity and cognitive impairments, followed by social issues (social isolation, caregiver burden) |

| Number of included studies (articles): 10 (10) | Age of included study participants: 70–99 years | Inclusion criteria: geriatric evaluation could consist of a geriatric consultation (i.e., specialist in geriatric or elderly medicine involving multidimensional assessment) or GA (i.e., evaluation of ≥ 3 of the following domains, preferably with validated assessment tools: Cognitive function, mood/depression, nutritional status, ADL, IADL comorbidity, polypharmacy, mobility/falls or frailty and performed by a cancer specialist, healthcare worker or (research) nurse) | • Effect of GE on treatment decisions considered in six studies. Treatment changes for approximately, 1/3 of patients, with most modifications to a less intensive treatment option | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): mixed/mixed/mixed | • Nononcologic interventions were recommended to over 70% of patients across six studies | ||||

| Clinical setting: mixed (oncogeriatric, MDT thoracic oncology) | • Frequently recommended interventions were social interventions (median 38%), modification to medication (median 37%), followed by nutritional interventions (median of 26%). Intervention for psychological, cognitive, impairments, mobility/falls risk or comorbidity were all recommended for a median of 20% of patients | ||||

| Hamaker (2018) [18]-update to Hamaker (2014) | Included study designs: randomised trials, cohort studies | Older adults: no limit | Introduction: not defined | To summarise all currently available data on the effect of a GE on oncologic treatment decisions, the implementation of nononcologic interventions and the impact on treatment outcome for older adults with cancer | • 11 studies compared treatment decision before and after GE, and adjustments were made in a median of 28% of patients (range 8%–54%). Mostly to a less intensive treatment option |

| Number of included studies (articles): 35 (36) | Age of included study participants: mean/median age 74–83 years | Inclusion criteria: geriatric evaluation could consist of a geriatric consultation (i.e., specialist in geriatric or elderly medicine or geriatrician consultation) or a multidisciplinary paramedical team evaluation (i.e., evaluation of at least three geriatric domains by two or more (para)medical healthcare professionals) or a GA (i.e., evaluation of ≥ 3 of the following domains, investigated with a validated assessment tool: cognitive function, mood/depression, nutritional status, ADL, IADL, comorbidity, polypharmacy, mobility/falls or frailty and performed by a cancer specialist, healthcare worker or (research) nurse | • 19 studies reported on nononcologic interventions. Common intervention included addressing social issues (39%), nutrition (32%) and polypharmacy (31%). GA-based interventions were recommended to a median of 70% of patients | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): mixed/mixed/mixed | • 13 studies reported on the effect of GE on treatment outcomes. Positive effect on treatment completion (higher completion in 3/4 studies), and treatment toxicity or complications (positive effect in 5/9 studies), lower rates of mortality (2/7 studies), heterogeneous results for healthcare use (in 8 studies) | ||||

| Clinical setting: mixed (oncogeriatric, MDT thoracic oncology) | • Two of three RCTs found positive effect of GE on quality of life or physical functioning | ||||

| Hamaker (2022) [29]-update on Hamaker (2018) | Included study designs: randomised control studies, cohort studies | Older adults: no limit | Introduction: referred to as a ‘multidimensional assessment of health status across somatic, functional and psychosocial domains’ | To summarise currently available data on the effect of a geriatric assessment on the treatment of older patients with cancer for oncologic treatment decisions, the implementation of nononcologic interventions, doctor–patient communication and the impact on treatment outcome. A second aim was to assess differences in impact based on the way the geriatric assessment is implemented | • Across 21 studies, treatment decisions were modified in a median of 31% of patients (range 7%–56%), mostly to less intensive treatment option. Modifications were higher when conducted by multidisciplinary team compared to assessment by oncology team or geriatric consultation |

| Number of included studies (articles): 61 (65) | Age of included participants: mean/median age 68–83 years | Inclusion criteria: A GA consist of a geriatric consultation (i.e., specialist in geriatric/elderly medicine or geriatrician consultation), an assessment by the oncology team (i.e., use of validated assessment tools on at ≥ 3 domains of cognition, mood/depression, nutritional status, ADL, IADL, comorbidity, polypharmacy, mobility/falls, or frailty and performed by cancer specialist or healthcare provider), or a multidisciplinary team evaluation (assessment of at least three geriatric domains by two or more (para)medical healthcare professionals) | • 33 studies reported on GA-based interventions. One or more interventions were recommended to a median of 72% of patients | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): mixed/mixed/mixed | • Across three RCTs, GA led to more age-related discussions and improved communication | ||||

| Clinical setting: mixed | • 21 studies reported on effect of GA on treatment outcomes. In most studies, GA led to lower treatment toxicity/complications, higher treatment completion (in 6/9 studies) and improved quality of life (in 4/6 studies) or physical functioning (in all three studies) | ||||

| Chuang (2022) [52] | Included study designs: RCTs. | Older adults: ≥ 65 years | Introduction: reference to published guideline and cancer literature | To evaluate whether implementation of a CGA could reduce treatment-related toxicity in older patients undergoing nonsurgical cancer treatments | • Meta-analysis of six RCT evaluating CGA-based intervention for non-surgical cancer treatment compared to usual care demonstrated association with CGA-based interventions and reduced incidence of Grade 3+ toxicity, and a lower rate of reducing treatment dosage during treatment |

| Number of included studies (articles): 6 (6) | Age of included study participant: ≥ 70 years (n = 5); ≥ 65 years (n = 1) | Inclusion criteria: not defined | • There was no significant difference for early treatment discontinuation, treatment modification (i.e., reduction in treatment intensity), treatment delay or hospitalisation or mortality between CGA-based interventions and control groups | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): mixed/mixed/mixed | |||||

| Clinical setting: oncology | |||||

| Disalvo (2023) [51] | Included study designs: RCTs phase 2 pilot RCTs, prospective cohort study | Older adults: mean or median age ≥ 65 years | Introduction: reference to published recommendation/position statement | To summarise the data on the effect of a comprehensive geriatric assessment or geriatric assessment with intervention on cancer care, treatment completion, adverse effects, GA domains and survival | • CGA/GA impacted decisions around treatment intensity and improved health-related quality of life scores |

| Number of included studies (articles): 10 (10) | Age of included study participant: NR | Inclusion criteria: not specified in methods—noted studies were GA-evaluated and < 3 domains were excluded | • CGA/GA increased treatment completion, and increased supportive care interventions | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): mixed/NR/systemic therapy | • CGA/GA reduced grade 3 or more chemotherapy toxicity | ||||

| Clinical setting: oncology | • CGA/GA did not impact on survival rates | ||||

| Anwar (2023) [50] | Included study designs: RCTs | Older adults: ≥ 65 years | Introduction: reference to literature and cancer literature. | To synthesise information on the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of comprehensive geriatric assessment (with or without implementation of recommendations) compared with usual | • Meta-analysis of 17 RCTs found that treatment toxicity was significantly lower in intervention group compared to usual care; however, no differences reported for mortality risk, treatment reduction, early treatment discontinuation and hospitalisation |

| Number of included studies (articles): 17 (19) | Age of included study participant: mean age 72–80 years | Inclusion criteria: CGA should have been conducted by a geriatrician, a trained nurse, a multidisciplinary geriatric team, or by using a combination of validated, evidence-based tools and criteria applied by research personnel. No limits on number or types of domains for CGA inclusion | • No significant differences in functional outcomes between intervention and control group reported across 8 RCTs | ||

| Sample (cancer type/stage/treatment): mixed/mixed/mixed (combination n = 9, chemotherapy n = 4, surgery, n = 3, radiotherapy n = 1) | • Only 6 RCTs evaluated quality of life, with mixed results reported | ||||

| Clinical setting: mixed (any clinical setting) | • No studies reporting on cost-effectiveness | ||||

- Abbreviations: ADL = activities of daily living, BMI = body mass index, CCI = Charlson comorbidity index, CGA = comprehensive geriatric assessment, CIRS/CIRS-G = cumulative illness rating scale, cumulative illness rating scale-geriatric, GA = geriatric assessment, GDS = geriatric depression scale, IADL = independent activities of daily living, MMSE = mini-mental state examination, NR = not reported, RCT = randomised controlled trials.

- ^ Based on study recruitment.

- &Based on 12/31 studies.

- †Based on 17/19 studies reporting on mean patient age.

- ‡2 studies had unclear study designs.

- §Noted that identified GA domains classified into recommended GA domains: functional status, comorbidities, psychological disorders, cognitive ability, nutrition, social and financial support, polypharmacy, falls/imbalance, urinary, vision/hearing, delirium, sexual function, dentition, and goals/preferences of care.

- +Calculated based on separate search strategies used.

3.2. Overlap of References

A total of 487 publications (range 6–83 publications) were included across 29 reviews (Supporting Table 2). Only 35% of studies were reported across two or more reviews. The lack of overlap was likely due to broad review aims, diversity of inclusion criteria and the range in publication dates.

3.3. Quality Assessment

None of the 29 reviews met all 16 of the AMSTAR-2 criteria. However, over 80% of the AMSTAR-2 criteria were met in 22 reviews [16–20, 29–32, 35, 37–41, 45–47, 49–52]. Most reviews (n = 24) [16–19, 29–33, 35–41, 43–47, 50–52] assessed risk of bias. Only five reviews [19, 33, 40, 50, 52] included a meta-analysis, with many indicating meta-analysis was not possible due to data heterogeneity. Reviews were not excluded based on the quality assessment (Supporting Table 3).

3.4. What Constitutes a GA in Cancer Care?

3.4.1. Definition of GAs in Cancer Care

Of the 29 reviews, only three reviews [34, 41, 52], explicitly defined GAs based on guidelines such as the SIOG practice guidelines, NCCN or ASCO guidelines. Seven reviews [27, 28, 31, 37, 38, 42, 47] defined GA as screening only, without specifying the care plan. A further five [30, 31, 39, 40, 51] reviews used definitions based on published recommendations or position statements, and nine reviews referred to definitions used in existing cancer research [32, 33, 35] (n = 3), general literature [20, 36–38, 49] (n = 5) or both [50] (n = 1). Four reviews [16, 19, 45, 46] did not explicitly define what they considered a GA. Despite some reviews referring to guidelines and recommendations, the number and types of domains considered essential to GAs differed across reviews, from no limit [50] or any combination [47] to assessment of at least five domains [48].

3.5. How Is a GA Conducted?

Twelve reviews [16–19, 29, 31, 39, 43, 47, 49–51] discussed conduct of GAs. Despite variability, clinician assessment using validated measures was commonly reported, although patient self-assessment, clinical interviews or geriatrician-led consultations were also reported. Seven reviews [16, 19, 34, 36, 43, 47, 49] reported GA completion time which ranged from 8 to 120 min.

3.5.1. GA Domain Assessments

Mapping the common domains included in each review (n = 24) [16, 17, 19, 30–49, 51] to the NCCN Older Adult Oncology guidelines [8], only eight reviews [16, 17, 19, 33, 34, 42, 49, 51] included all recommended domains. A summary of the common measures and assessments reported across reviews mapped to the NCCN [8] recommendations is provided below and in Table 2.

| Domains | Common tools | N reviews where tools were common∗ | N reviews that reported tools (%) | NCCN-recommended tools (Y/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported function and mobility | Katz (for ADL) | 9 | 12 (75) | Y |

| Lawton–Brody (for IADL) | 9 | 11 (82) | Y | |

| Falls history | 3 | 8 (37) | Y | |

| Objective function and mobility | TUG/GUG | 5 | 12 (42) | Y |

| Comorbidity | Charlson | 7 | 12 (58) | Y |

| CIRS-G (including CIRS) | 6 | 12 (50) | Y | |

| Social functioning and support | MOS social support/activity survey | 2 | 10 (20) | Y |

| Cognition | MMSE | 12 | 15 (80) | Y |

| Psychological | GDS (including short forms) | 12 | 15 (80) | Y |

| Nutrition | MNA (including short form) | 8 | 13 (61) | Y |

| BMI | 4 | 13 (31) | Y | |

| Polypharmacy | n of pills | 7 | 8 (87) | N |

| Performance status∧ | ECOG-PS | 8 | 9 (89) | Y |

- Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index, CIRS/CIRS-G = cumulative illness rating scale, cumulative illness rating scale-geriatric, ECOG-PS = Eastern cooperative oncology group-performance status, GDS = geriatric depression scale, MMSE = mini-mental state examination, MOS = medical outcomes study, TUG/GUG = timed up and go, get up and go.

- ∗Tools were considered common if they used at least in 20% of studies within the reviews and commonly used across two or more reviews.

- ∧Some reviews reported this as a measure of functional status.

Function and mobility (n = 24 reviews): They were commonly assessed using NCCN-recommended tools Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living [53] (n = 9) [16, 17, 19, 31, 37, 38, 41, 42, 47] and the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) scale [54] (n = 9) [16, 17, 19, 31, 32, 37, 38, 41, 42, 47]. Lack of adherence to NCCN recommendations (in the last 6 months) was seen in the reporting of timeframe for falls history. However, studies across two reviews [19, 22] had varying timeframes (e.g., past three or 6 months) or did not specify timeframe. Measurement of falls using self-reported fall history or falls risk tools were reported in eight reviews [16, 19, 32, 33, 35, 37, 41, 42]. Objective measures such as the timed up and go [55] were also reported across the 12 reviews [16, 17, 19, 31–33, 36, 37, 42, 43, 45, 48].

Of the 16 reviews [16, 17, 19, 31–36, 40, 42, 43, 47–49, 51] where comorbidity was a commonly included GA domain, twelve [16, 17, 19, 31–33, 35, 36, 40–42, 48] specified measures are used. The NCCN-recommended Charlson comorbidity index [56] and cumulative illness rating scale (including CIRS-G) [57, 58] were commonly used within and across seven [16, 17, 31, 33, 35, 40, 41] and six reviews [19, 31, 36, 41, 42, 48], respectively. Another NCCN-recommended tool, haematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index [59], was reported in a single study by Puts et al. [19] and Salazar et al. [40].

Social functioning was commonly included in the GA across 14 reviews [16, 17, 19, 30, 36, 37, 39, 42, 43, 45, 46, 48, 49, 51]. Of the 12 reviews [16, 17, 19, 31–33, 35, 36, 40–42, 48] that specified measures, the NCCN-recommended medical outcome study subscales social activity survey and/or social support [60] were commonly used within and across two [16, 41] of the 10 reviews [16, 19, 33, 36, 37, 41, 42, 45, 46, 48], while six reviews used nonstandardised assessments [17, 42, 45, 46, 48] or nonrecommended tools [45].

Of the 20 reviews [14, 15, 17, 25–32, 34, 37–40, 42] that included cognitive function as a GA domain, 15 reviews [16, 17, 19, 31–33, 35–37, 41, 42, 45–48] specified tools used. These reviews primarily reported use of the NCCN-recommended mini-mental state examination [61] within and across reviews (n = 12 reviews) [16, 17, 19, 31, 33, 35–37, 41, 42, 47, 48]. Two reviews [37, 41] also reported studies using the Blessed Concentration Tool [62].

Nutrition Status was commonly included within a GA across 19 reviews [16, 17, 19, 30–37, 39, 42–44, 47–49, 51]. Commonly used tools across the 13 reviews [16, 17, 19, 31–33, 35–37, 41, 42, 47, 48] that specified measures was the mini-nutritional assessment [63], while a further four reviews [16, 19, 36, 41] used body mass index. Use of the mini-nutritional assessment short forms was reported in four reviews [19, 22, 35, 37].

Mood was a common domain included within a GA across 20 reviews [16, 17, 19, 30–37, 39, 42–44, 46–49, 51]. Tools used were specified in 15 reviews [16, 17, 19, 31–33, 35–37, 41, 42, 45–48]. Mood was commonly assessed using the NCCN-recommended geriatric depression scale [64], with only one review [46] reported using a nonrecommended tool. Another NCCN-recommended tool, the Mental Health Inventory (MHI-17), was reported as a common tool (11%), in Lee et al. [41]. Use of the geriatric depression scale short form was reported in three [19, 22, 46] reviews. Surprisingly, despite wide use in cancer more broadly, the NCCN-developed Distress Thermometer [65] was not commonly included.

Polypharmacy was commonly included as a GA domain in 14 reviews [16, 17, 19, 31–35, 42, 44, 47–49, 51]. In eight reviews [16, 19, 31–33, 35, 41, 42] where measures were specified, NCCN-recommended tools were not used. Most reviews reported this was determined by the number of medications, although definitions of polypharmacy varied within and across three reviews [33, 35, 42] (range > 3 to > 8).

In summary, commonly reported tools within and across reviews are mapped to NCCN recommendations, although there was some variation in timeframes for falls history, use of short forms for nutritional and depression assessment and lack of validated tools used to assess polypharmacy.

3.5.2. Use of GA Results

Most reviews [16, 19, 30–34, 37–40, 42–48] (n = 18) reported the predictive value of GA on outcomes. In Lee et al. (2022)’s review [41], the most common reason for conducting GAs was to determine the association between the GA and clinical outcomes. In 11 reviews [16, 19, 30, 31, 34–36, 38, 40, 42, 44], GA results were used to categorise patients as fit or unfit/frail and/or identify frailty. The criteria used for frailty varied across and within reviews. For example, in Hamaker et al. [31], eight studies identified frailty based on dependency for activities of daily living, three or more comorbidities or one or more geriatric conditions. However, many of these reviews did not specify how the summary score or categorisations impacted treatment decisions.

There were 14 reviews [16–19, 29, 34, 36, 38, 39, 41, 43, 48, 50–52] that explicitly reported the use or impact of GAs in guiding or adjusting treatment decisions. Only three reviews [19, 34, 48] specified criteria for adjustments, with impairment in functional status or malnutrition reportedly resulting in change to the treatment plan. In an additional review [38], the authors reported a significant correlation in activity of daily living scores and changes to treatment decisions in two of three studies. In Okoli et al. (2021)’s scoping review [49] describing integration of GAs in oncology, in two models, results were reviewed by a multidisciplinary team and a treatment plan formulated, and in another model, an initial review was conducted by a trained nurse who provided a summary to the treating team and relevant allied health professionals for review.

Only 10 reviews [16–18, 29, 34, 39, 48, 50–52] reported that referrals or interventions were recommended or implemented to address identified issues from the GA. Of the 10, seven [17, 18, 29, 34, 39, 48, 51] specified the number and or type of interventions recommended.

3.6. Implementation of GAs in Oncological Settings

Only three reviews [20, 48, 49] reported barriers and facilitators of GA, with only two [20, 49] specifying implementation or integration of GAs as a review aim. Lack of time and resourcing [20, 48] and insurance reimbursement [48] were identified. In Okoli et al. (2021), use of patient-led or self-reported assessments, computer-based or ‘mini’ versions of GAs were reported to facilitate GA implementation. In their realist review of implementation of GAs in oncology, McKenzie et al. [20] posited (1), ‘leveraging on non-specialists’ such as protocolisation of GAs to address workload barriers, (2) ‘creating a favourable health economics’ to address lack of funding, (3) ‘establishing the use of GA in cancer care’ such as using screening tools to identify patients that require a full GA to address practicality barrier and (4) ‘managing limited resources’ such as using technology to automatise processes as strategies to facilitate GA implementation.

3.6.1. Who Conducts the GAs?

Across and within reviews that described the healthcare professionals’ roles in conducting GAs (n = 12) [16–19, 29, 36, 43, 47–51], there was no consensus on staff responsibility. For example, in Feng et al. [47], the GA was delivered by a range of individuals including nurse practitioners, student doctors, research assistants and medical doctors, whereas in Szumacher et al. [43], majority of studies (n = 4, 57%) reported that the GA was delivered by a geriatrician, with three studies reporting patient self-assessment. Caillet et al. [48] reported a multidisciplinary team approach. The use of geriatrician led assessments varied across reviews, from four studies reported in Puts et al. [19] to 28 studies reported in Hamaker et al. [29].

Only six reviews [16, 36, 47, 49–51] specified whether the individual(s) were trained and there was variability within and across reviews.

3.6.2. Timing of GAs

Of the 12 reviews [16, 19, 20, 30, 34, 36, 40, 41, 43, 47, 49, 51] that reported on timing of GAs, majority noted that the GA was typically conducted prior to cancer treatment. An additional three reviews [32, 45, 46] specified criteria of assessments conducted prior to treatment. Across reviews, the GA was recommended to be conducted prior to treatment to guide treatment decisions, determine the predictive value of GAs on adverse health outcomes or identify impairments and provide interventions to optimise health outcomes. None of the reviews explicitly discussed the use of GA for ongoing monitoring during treatment, although six reviews [16, 30, 34, 36, 41, 43] reported that repeat GAs (e.g., before and after treatment) were conducted in some included studies, to explore changes in patient health status [30, 43].

3.6.3. Reporting of Successful Implementation

Reporting of implementation outcomes was only addressed in four reviews [16, 36, 43, 49]. However, outcomes were limited to feasibility and acceptability of conducting GAs. For example, in Puts et al. [16], acceptability reported in 4/73 studies found that most patients (75%) could complete the GA without assistance and were satisfied with the length and content. One review [29] reported that standardised protocols facilitated greater implementation of GA-guided interventions. Disalvo et al. [51] reviewed the extent to which the included studies maintained or improved fidelity to the GA and management intervention and found there was generally high completion rate in the GA intervention arm; however, studies did not report on strategies used to maintain or improve fidelity. Other outcomes of implementation success such as cost-effectiveness or sustainability were not reported or discussed in these reviews.

4. Discussion

In this umbrella review, we identified 29 reviews that described the use of GAs for older adults with cancer. There were inconsistencies across reviews in relation to domains included in Gas, and assessments were typically conducted prior to initiating treatment. Few reviews explored implementation of GAs in routine cancer care.

A traditional CGA involves the development and implementation of care plans to address identified issues [6]. Our results highlight in the context of cancer, most research has focussed on the assessment component, although a few recent reviews [50–52] have reported on the effect of GA-led management. As such, majority of reviews defined a GA as a systematic evaluation of an older person using validated tools. However, reviews varied in the number and types of domains considered essential within a GA, possibly due to some reviews published prior to availability of international guidelines. Despite this variability, common domains and tools reported reflect the recommendations included in the NCCN [8] and ASCO guidelines [9]. This suggests there is general consensus that the GA should consist of an assessment of function and mobility (including falls), depression, cognition, nutrition, commodities, social functioning and support and polypharmacy. Similar to guideline recommendations [8–10], most reviews reported that the GA was conducted before cancer treatment. Interestingly, studies within six reviews reported additional GAs conducted during or after treatment. However, these reviews did not discuss the use of repeated GA to monitor patients during treatment. Given that studies have demonstrated changes in patient outcomes, during and after treatment [65], future studies should determine the impact of assessment of multiple geriatric domains across the treatment trajectory to confirm appropriateness of treatment and optimise patient outcomes.

4.1. Implementation of GAs in Cancer Care

The implementation science literature highlights health service change is most successful when staff feel confident in their ability and perceive they have sufficient resources to undertake practice change [66]. Our review identified a lack of focus on training for individuals administering assessments across reviews. In Hamaker et al. [18], more nononcologic interventions (e.g., psychological intervention, polypharmacy optimisation) were recommended for patients when the GA was performed by a geriatrician compared to cancer clinicians. This suggests the importance of training on geriatric principles for both individuals administering and interpreting GA results.

An important consideration when implementing GAs is to identify who will conduct the assessments [67]. Reviews reported a range of individuals, including the patient, multidisciplinary team, nurse and geriatricians. Self-administered assessments including computer-based assessments can reduce strain on human resources and time but health and digital literacy may impact on feasibility [49]. Although feasibility was not widely assessed, patient acceptability was reported in a small number of studies across reviews. Time and resources were commonly reported barriers, with reviews reporting large variability in completion time, suggesting inconsistency in the GA definition (screening vs. management) and tools used. This raises the question of feasibility of conducting GAs in busy oncology clinics.

In response to barriers and to facilitate GA-guided management, ASCO, in collaboration with the Cancer and Ageing Research Group, created the Practical Geriatric Assessment (PGA) tool which covers the eight domains (physical function/performance, functional status, nutrition/weight loss, social support, psychological, comorbidity, cognition), as well as identifying chemotherapy-related toxicity [10]. In our umbrella review, whilst majority of the common measures reported mapped to the NCCN recommendations, there was variability, suggesting that the measures used will depend on context specific issues such as resource availability. Therefore, the PGA tool may provide a feasible yet standardised approach to assessing geriatric domains and thus facilitate adoption as standard practice within cancer care. Further dissemination of this tool through educational modules and research to determine feasibility and uptake in practice is needed.

The reviews included in our umbrella review reported that GA results were used to predict or determine the association between impairments and outcomes and identify impairments or frailty and were associated with changes in treatment plans. Although exploration of GA-based interventions was not our aim, there were 10 reviews reporting on the number/type of interventions recommended following identification of GA impairments. While selection of tools and referral services or interventions may depend on local resources and preferences, protocols or pathways should be in place to facilitate interventions and ensure timely and appropriate follow-up care is provided when impairments are identified.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

This umbrella review is not without limitations. As an umbrella review synthesises the systematic review evidence, the effectiveness of umbrella reviews may be limited by the diversity in the aims, outcomes or reporting of the included systematic reviews [24]. In our umbrella review, many included reviews did not report tools used for all domains measured. This impacted on comprehensiveness of data reporting. Furthermore, there were heterogeneity of data in terms of definitions of GA, hence contributing to the lack of overlap in references across reviews. The inconsistency in GA definition also contributed to the large range in the time it takes to complete a GA. This could potentially impact on clinician’s perceptions of feasibility within clinical practice. However, umbrella reviews systematically integrates and aggregates results across systematic reviews highlighting similarities and conflicting information presented across included reviews [24]. Consolidation of review evidence allows for understanding for implementation of these assessments in routine care. Inclusion of recommended GA domains needs to be weighed against time and resource barriers and short-form assessments such as the PGA may improve screening feasibility. However, screening alone is not enough; for optimal cancer care, the screening results need to not only guide cancer treatment decisions but must also act as a conduit for appropriately tailored follow-up care for older people with cancer.

5. Conclusion

This umbrella review provides an overview of what a GA is in the context of cancer and how implementation of GAs is reported for older adults with cancer. This review highlights the importance of using consistent terminology and consistency in domains included to facilitate increased evidence-based research and implementation of GAs. Future research could also examine the feasibility of the ASCO-developed PGA tool developed to address barriers of GA implementation. Furthermore, there was a lack of reviews reporting on implementation of GAs. Use of implementation science frameworks to guide and evaluate use of GAs is crucial in facilitating the use of GAs as part of treatment decision-making and management as well as sustainability of implementation.

As such for clinical practice, selection of GA domains should represent a holistic assessment of the patient. Guidelines or recommendations by ASCO [10], NCCN [8] and SIOG [11] can be used to guide domain assessment. The tools used to assess each domain should be selected based on local context and resourcing to ensure feasibility. The Practical Geriatric Assessment may improve feasibility of screening as part of a GA. Use of implementation frameworks or criteria to guide and evaluate GA implementation to ensure effectiveness and sustainability of GA, this includes training for GA administration or interpretation of results.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript is an umbrella review. Articles included have been referenced in the manuscript. All data extracted from the reviews were summarised in the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.