Telemedicine Using Telephone for Consultation in Haemato-Oncology and Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Realist Review

Abstract

Background: Telemedicine, use of telecommunication and information technology to provide remote healthcare, is an alternative to face-to-face consultations to support sustainability, increase quality and improve patient experience at lower cost. Using telephone in routine follow-up potentially improves healthcare access, convenience, and choice. However, research identifies health disparity and inequality for some. We focus on haemato-oncology due to the patients’ clinical and psychosocial vulnerability, complex disease behaviour, treatment, and care needs.

Objective: To undertake a realist review of the relevant literature to develop theories of what works, for whom, why and under what circumstances when telephone consultations are used for routine follow-up in haemato-oncology and haematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Methods: Electronic database, grey literature and forward citation searches (using Google scholar) identified studies assessing outcomes related to telephone consultations in haemato-oncology and HSCT patients. Included studies were assessed for relevance and rigour. Relationships between contexts (C), mechanisms (M), and outcomes (O) were extracted from sources. CMO configurations were developed and refined iteratively. A stakeholder group of cancer patients contributed to their refinement.

Results: Eleven included studies were synthesised. Final programme theory was developed from 19 CMOCs and included five inter-related themes: healthcare professional (HCP) relationship, confidence in telephone telemedicine, receiving care closer to home, COVID-19 and service resources. Findings highlight the importance of considering context at different levels: individual, interpersonal, institutional, and infrastructural. Final theory shows that key contextual factors (e.g., patient-HCP relationship) influence the workings of key mechanisms (e.g, trust and adherence) in producing outcomes and explain why, how and for whom telephone consultation works in this context.

Conclusions: This is the first realist synthesis in this area. The final programme theory suggests that individual patient-related contextual factors and the HCP-patient relationship should be considered by health professionals offering telephone consultations since these factors likely influence health inequality and patient safety.

1. Introduction

Telemedicine was first defined over 20 years ago as ‘the delivery of healthcare services, where distance is a critical factor… using information and communication… for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation’ [1]. It has potential to transform how people engage in and control their health care, empowering them to manage it in a way that is right for them [2]. It can deliver superior care, greater efficiency, flexibility in scheduling and huge economic savings [3] when used with the right patients in the right setting, by adequately trained personnel. Telemedicine encompasses a broad church of approaches that include remote consultations by telephone and video where patients converse live with their healthcare provider in place of face-to-face appointments. Governmental support for the implementation and uptake of telemedicine including remote consulting in health care is strong nationally and internationally [2, 4, 5], reflected in the recent NHS Long Term Plan commitment that ’every patient will get the right to telephone or online consultations’ [2]. However, research has shown that whilst there are many potential benefits, e.g., improved healthcare access, convenience and choice [6–9], it has not worked for everyone.

The implementation of telemedicine with telephone and video consultations was accelerated rapidly by the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic changed the way that people receive and perceive health care globally. It generated considerable UK investment in video consultation, with anticipation that this would enter standard clinical practice [10]. However, despite provision of funding, video consultation uptake remained static (< 0.6% general practice consultations) during and following the pandemic due to IT problems, reliance on in-person visual assessment, perception that video-consulting was additional work and concern that video would benefit those with IT skills and enforce health inequity for those without them [11]. Conversely, the ‘pandemic effect’ boosted telephone consultations from 2019 levels of 13% to 26% in 2022 [12]. A survey of NHS care episodes [13] corroborated this dominance of telephone consulting. However, as Greenhalgh highlights, relatively little research exists on this modality [10]. Furthermore, Rosen identified several risks with remote consultations, the majority of which were telephone, such as a shift towards more transactional consultations, care quality issues (missed diagnoses, safeguarding and overinvestigation) and increased patient responsibility to self-examine or navigate services [14]. Suggested mitigation measures included digital inclusion strategies, enhanced safety netting, staff training and support.

We know relatively little about patients’ or healthcare professionals’ (HCPs) satisfaction with telephone consulting as associated quantitative studies have been underpowered, rendering results inconclusive [9, 15]. Satisfaction is known to be linked with acceptability [16]. A few studies have cited positive findings regarding acceptability to patients of telephone follow-up in cancer services [17–20]. However, some participants in one study [17] reported negative experiences; they described consultations as rushed and impersonal, leaving them feeling isolated and less reassured.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused specific issues for immune-compromised people such as HSCT patients and those with a haemato-oncological diagnosis. Blood cancers are common—they are the fifth largest group of cancers with more than 200,000 people diagnosed each year and the third largest cause of cancer death [21]. For many, the only potentially curative treatment is HSCT. Each of the 48,512 European transplant recipients per year [22] requires specialist follow-up to manage complex physical and psychosocial sequalae, minimise morbidity and mortality and optimise outcomes. During the COVID-19 pandemic, clinically vulnerable HSCT recipients and people with haemato-oncological diseases appeared to benefit from remote consultations. Risk of COVID-19-related death in blood cancer patients was highlighted through the health analytics platform OpenSAFELY [23]. Remote consultations mitigated risk of nosocomial COVID transmission and reduced morbidity and mortality rates [24].

The extreme vulnerability and complexity of this group renders them different from those with cancer more generally [23]. Clinical, physical and psychosocial care needs of haemato-oncology and HSCT patients are unpredictable, with unstable health characterising early posttreatment and longer-term experiences [25]. The highly specialist, complex health needs of this group mean telemedicine follow-up schedules are potentially more difficult to institute and manage. Safe and effective implementation requires knowledge and understanding of the role of telephone consultation, a complex intervention, in this setting. Such knowledge is currently lacking. This synthesis used realist methods to explore why, for whom, how and under what circumstances, telephone consultations work (or do not work) in routine haemato-oncology and HSCT follow-up.

2. Methods

A realist synthesis was undertaken in accordance with Realist And Meta-Narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) reporting standards [26]. Realist synthesis is an approach to reviewing research evidence on complex issues which provides an explanation of how and why interventions work (or do not work), in particular contexts or settings [27]. Since interventions are embedded in multiple social systems, and events and social conditions are affected by relationships and behaviours, the same interventions are rarely, if ever equally, effective in all circumstances. This is because of contextual factors. Realist research explores causal links between the context in which healthcare interventions occur, the mechanisms which are triggered by the intervention in specific contexts and the specific outcomes that result [28]. Therefore, a realist approach to data synthesis reveals the relationships between contexts, mechanisms and outcomes (CMOs), offering an explanation (known as a programme theory) of why an intervention achieves what it does [29].

2.1. Synthesis Questions

- •

How, why and for whom does telemedicine work and in which contexts?

- •

What outcomes (positive and negative, intended or unintended) are produced or have been reported by patients and HCPs participating in routine monitoring and follow-up care provided by telephone?

- •

What mechanisms (resources offered by telemedicine, and responses to the resources) are linked causally to the outcomes occurring?

- •

What contextual factors impact on whether (or the extent) that mechanisms are triggered to produce outcomes (positive and negative, intended or unintended) in routine monitoring and follow-up care via telephone consultations?

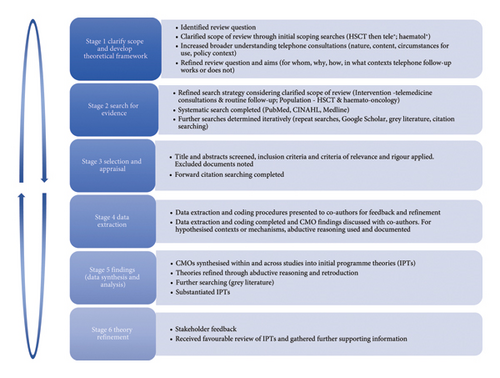

- 1.

Clarifying scope

-

Telephone consultations for follow-up of people with blood cancers have similar principles to HSCT follow-up and thus both were included in this review thereby offering a wider body of literature to draw from. Telemedicine is a complex intervention incorporating a range of elements such as clinical and symptom assessment and management, treatment planning, information delivery, support and onward referral. Initial scoping searches using broad terms integral to the intervention (telemedicine (tele∗), and population (haematol∗) under study, helped to ‘map the territory’ and identified a range of sources crossing traditional disciplinary and sector boundaries [26]. This overview offered insights and appreciation of various models of telemedicine consultation and the location of the existing theories on how such consultations are theorised to work, or not, in different contexts. This process of familiarisation or concept mining [31] was helpful in defining the search parameters and inclusion/exclusion criteria for this review.

- 2.

Searching for evidence

-

Three different search methods were utilised and outlined below.

- •

Systematic Search in Databases

-

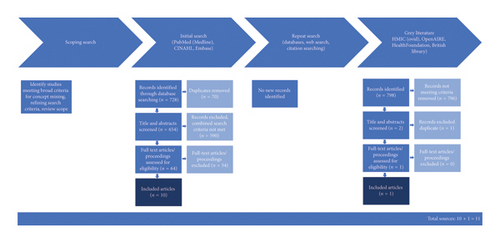

A systematic database search of PubMed (Medline), CINAHL (via EbscoHOST) and Embase (via EMBASE.com) was initially performed in September 2021. Alerts for new articles were set up in PubMed to facilitate addition of new publications during the synthesis. The start date was set at 2000 to capture advances in the 1990s in telecommunication technology (greater connectivity and coverage, network expansion and increasing access to cell phones) and declining associated costs [32] and growing body of evidence for clinical and cost effectiveness driving telephone consulting into health policy and relevance to health services today. No set end date enabled capture of recent studies; including those reporting on follow-up consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic. A flowchart summarises search results (Figure 2). Searches were rerun in February 2022 and May 2024 and revealed no new relevant papers.

-

Search terms for databases comprised two concepts [1]: intervention (telemedicine consultations AND routine follow-up) [2] and population setting (HSCT or haemato-oncological disease) and were guided by keywords, MeSH terms, topic indexing and search strategies reported in retrieved documents.

- •

Grey Literature

-

Search terms were adapted to the different databases as follows: HMIC (Ovid) (Haemato∗ OR Hemato∗AND Tele∗ OR Remote, OpenAIRE—Haematology AND Telemedicine), Health Foundation (Telemedicine OR Remote consultation), British Library (Telemedicine haematology) and Google Scholar (Telemedicine AND haematology).

- •

Citation Searching

-

A search of reference lists from identified papers was performed along with forward citation searching using Google Scholar.

- •

- 3.

Selection and Appraisal

-

Titles and abstracts were screened (by MK) followed by screening of all included full-text articles using inclusion criteria:

- •

Adult participants of telephone telemedicine consultations for routine follow-up (patient and HCPs).

- •

People and setting of follow-up for a haemato-oncological condition or after HSCT.

- •

Scheduled, routine care.

- •

Acute care setting.

- •

Physician only, nurse only or physician- and nurse-led consultations.

- •

Document/journal article/peer reviewed paper/sources including blogs, webpages, diaries and newspapers written in English language.

- •

Publication 2000 onwards.

- •

-

Characteristics of included studies were extracted (Table 1), and papers were assessed for relevance, i.e., whether the study helped to refine or substantiate programme theories and rigour, i.e., the methods used to generate data were credible, plausible and trustworthy [28]. Document selection was driven by capacity to contribute knowledge to theory development. Selection and appraisal were cyclical with findings from one search informing a further search.

- 4.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

-

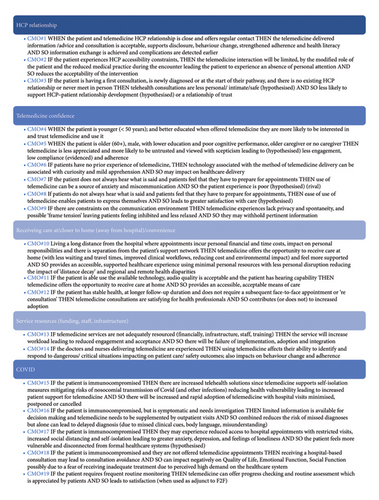

Several analytical strategies were deployed. Data extraction centred around identifying CMO configurations (and partial configurations, e.g., C-M, M-O or C-O) from included studies that helped to answer the synthesis questions. All authors independently extracted data from the initial four papers to ensure rigour and consistency. Where studies included both telephone and video consultations, data specific to video consultations alone were disregarded. The resulting configurations are presented as ‘if, then and so’ statements for ease of comprehension, and an example of realist synthesis data extraction is shown in Supporting file S1. Consolidation of CMO configurations followed, looking at how they related before synthesising and organising thematically (Figure 3).

- 5.

Theory Refinement

-

A local cancer services research user group comprising 8–10 service user—who had also informed the initial design for this review—provided comments on the CMOCs, initial programme theories and interpretation. Their comments verified the relevance of the initial theory; no new or missing information was identified. Pawson’s four contextual layers [27] were used to provide a framework for further analysis and organisation of CMOCs into a final programme theory (Figure 4).

| Author (year) | Condition(s) | Study design | Methods | Setting | Intervention type | Participants | Intervention purpose | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auret et al. [36] (2020) | Haematological malignancy | Mixed methods |

|

Australia Regional Cancer Centre | Combined video and face-to-face |

|

Follow-up |

|

| Dyer et al. [34] (2016) | HSCT | Quantitative | Cross-sectional survey and five other validated scales (FACT, Depression and Anxiety 21, cGvHD activity, Lee Symptom Scale, PTGI) | Sydney, Australia | Options surveyed inc TC, local haematologist, telemedicine, satellite | HSCT | Follow-up | 20% preference for telemedicine with 20% (n = 18) of these telehealth alone |

| Ellehuus et al. [43] (2021) | Haematological malignancy | Quantitative |

|

Denmark Dept of Haematology COVID-19 | Telephone or video |

|

Follow-up |

|

| Kumar et al. [38] (2021) | Haematological general (55% haematological malignancy) | Quantitative |

|

India COVID-19 | Telephone |

|

75% follow-up | Feasible 1/3 needed follow-up appointment |

| McGrath [33] (2015) | Haematological malignancy | Qualitative | Open-ended interviews | QA, Australia | Telephone and video | Purposive sample | Follow-up | Used to extend time between f2f appts |

| McGrath [41] (2015) | Haematological malignancy | Qualitative | Interviews | QA, Australia | None | Purposive sample (as above) | NA | Information-generated support care close to location |

| Palandri et al. [39] (2020) | Haematological general inc malignancy | Quantitative | Questionnaire (nonvalidated) | Bologna, Italy COVID | Telephone |

|

Follow-up, monitoring | Female prefer in-person, MPN prefer in-person |

| Postorino et al. [24] (2020) | Onco-haematology | Quantitative | Retrospective data analysis | Rome, Italy COVID | Telephone (with email support) | Haemato-oncology average age 57 y | Follow-up, monitoring | No adverse incidents, feasible delivery |

| Rochette et al. [35] (2021) | Onco-haematology | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews | Cancer centre, France |

|

|

Follow-up, monitoring on treatment |

|

| Zomerdjik et al. [40] (2021) | Malignant haematology | Mixed methods | Survey semistructured interviews (only interviews reported in this paper) | Melbourne, Australia COVID | Telephone and video | Purposive sample median 57 y 50% men | Follow-up |

|

| Banerjee and Loren [42] (2021) grey | HSCT survivors | Quantitative | Retrospective analysis | Haemato-oncology division, Philadelphia, USA | In-person and telephone | > 1 y post-HSCT | Follow-up | Driving distance superior predictor of long-term follow-up |

3. Results

3.1. Document Characteristics

Eleven papers met the inclusion criteria (Figure 2); they originated from Australia (n = 5), the United States (n = 2), Italy (n = 2), Denmark (n = 1), France (n = 1) and India (n = 1) (Table 1). All six quantitative studies used surveys, two with validated scales. The qualitative studies (n = 3) included purposively sampled populations and collected data through semistructured interviews. The remaining two evaluations used mixed methods in purposively sampled populations; both quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews were undertaken. Telemedicine using telephone—driven by the COVID pandemic—was the subject of five studies (quantitative = 4, mixed-methods = 1) that included data up until June 2020 reflecting the early pandemic response. Two studies [33, 34], explored perceived telemedicine preferences in patients without prior telephone consulting experience. No studies reported participant ethnicity, and HCP characteristics were generally not described except in Rochette’s [35] qualitative nurse-led telephone clinic study. Telephone consultation was the reported intervention in seven of the 11 included studies, while video and telephone consultations were delivered in the remainder. Overall quality of evidence was low to moderate; most quantitative studies had weak study designs (cross-sectional) and used nonvalidated tools (typically self-report, satisfaction and feedback) and none had control groups to allow comparison with usual care (in-person consultations). The qualitative and mixed methods studies, except one [36], included purposive samples.

3.2. Programme Theory

- 1.

HCP relationship.

- 2.

Telemedicine (telephone consultation) confidence.

- 3.

Receiving care at/closer to home (away from hospital/convenience).

- 4.

Service resources (funding, staff, infrastructure and training).

- 5.

COVID.

3.2.1. Theme 1: HCP Relationship

The importance of the HCP–patient relationship in telephone consultations is evident. Relationship factors were identified as enabling contextual drivers—supporting regular contact or encouraging uptake [35, 37] (CMO#1)—or barriers, acting as deterrents and reinforcing telephone consultations as inferior [36, 38] (CMO#3). Furthermore, the HCP relationship is important at various timepoints and with different contextual factors such as familiarity, frequent or established contact and ease of access. Auret offers the idea that when patients have no existing relationship with the HCP or service, because they are newly diagnosed or referred, there is an impact on the consultation experience [36]. It is reasoned by the researcher to be one that feels less personal or intimate impacting trust, disclosure and the future HCP relationship (CMO#2).

Similarly, the HCP–patient relationship can be compromised or constrained when patients feel that HCP access is obstructed by the mode of consultation offered. The concept of ‘humanised monitoring’ is described by Rochette, whereby the patient needs to give a face to the voice [35]. Rochette’s participants attached importance for them to ‘meet from time to time…to create a relationship of trust’ (CMO#2) suggesting an optimal combination of remote and in-person consultations.

3.2.2. Theme 2: Confidence in Telemedicine (Telephone Consultation)

Several authors [24, 36, 37] describe how different demographic groups connect with, and trust, telemedicine to a greater or lesser extent. For example, younger age and higher education levels were associated with responses of interest and trust [37] (CMO#4). Conversely, CMO#5 was informed by evidence that older adults may have underlying negative responses to telemedicine as lack of trust in the process, scepticism, and a lower regard for telephone consultation leading to lower compliance [37, 39].

Familiarity (or lack of) with this consultation mode can give rise to ‘curiosity’ and apprehension [36] (CMO#6), while the ability to hear using the available technology increases or decreases acceptability [36] (CMO#7) [24], (CMO#8). The described challenges for patients with hearing difficulties gives rise to the rival theory (CMO#8) where preparation for—and ease of telephone appointments (e.g., using amplified telephones and accompanied appointments)—can act as an enabling mechanism, leading to improved communication and better outcomes.

Environmental constraints [36, 40] such as background noise, visual distractions, ‘attending’ the appointment while working or travelling can impact on attention and offer an unfavourable environment for revealing sensitive information. Increasingly, patients undertaking remote consultations are juggling pressures of normal life, and where there is frame tension (i.e., interactions and distractions happening during but not connected to the appointment) or lack of privacy, patients may withhold important information and HCPs may be reluctant to discuss difficult or sensitive topics (CMO#9).

3.2.3. Theme 3: Receiving Care at, or Closer to, Home and Convenience

Disruption to everyday life, separation from support networks and cost (in terms of financial impact and/time away from work) are particularly powerful contextual factors impacting on the effectiveness of telephone consultations [41]. Patients felt more supported when a consultation mode minimised these factors [36, 41].

Without access to telephone consultations, patients living a long way from the treating centre [33, 36, 41] may experience health disparity and inequality due to ‘distance decay’ [41, 42] (CMO#10). Furthermore, it is theorised that tension arises when personal finances become a compelling driver for health decisions, i.e., patients may choose a cheaper consultation mode even if health interests suggest otherwise.

Quality, availability and suitability of telephone technology are important contextual factors for receiving care at home and impact its acceptability [36], and telephone consultations appear to be appropriate in the context of frequent monitoring [34, 36] (CMO#11). It emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic that this approach is especially useful where ‘checking in’ and routine assessment are indicated [34] (CMO#19). However, the frequency of telephone consultations is not described, and they are only experienced as “satisfying” by patients as an adjunct to planned face-to-face consultations. Furthermore, when telephone consultation results in additional face-to-face ‘reconsultation’ or double consultation due to missing signs/symptoms, this negatively impacts HCP’s satisfaction, acceptance and adoption [38] (CMO#12), as well as increasing clinical risk to patients and potentially healthcare costs.

3.2.4. Theme 4: Service Resources (Funding, Staff and Infrastructure)

Service resources are a frequently cited barrier to implementation of telephone consultation. Auret et al. [36] reason that poorly resourced programmes are more likely to fail in implementation, adoption and integration as they lead to increased clinician workload and reduced acceptance (CMO#13). Skilled, knowledgeable and experienced HCPs can benefit patient behaviour change and healthcare adherence and is an important contextual factor which triggers (or not) the ability to identify and respond appropriately to different situations by telephone [37] (CMO#14).

3.2.5. Theme 5: COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic generated several papers describing rapid implementation of telephone follow-up. This mode was especially helpful for those immunocompromised and mitigated risks of nosocomial transmission [37, 43] (CMO#15) but also caused consultation avoidance in response to the offer of hospital-based appointments due to fear of infection [43] (CMO#18). However, in the context of symptomatic patients needing investigation, the information gleaned through telephone assessment needed to be supplemented by in-person visits [37] (CMO#16). This reduction of hospital-based appointments, coupled with patients’ perception that the health system was suffering from high demand, increased fears of receiving inadequate treatment and risk of harm and reduced quality of life. Furthermore, as Ellehuus explains, for the vulnerable and immunocompromised, when human contact is reduced (due to fewer hospital visits, social distancing and self-isolation), the response of anxiety, depression and loneliness may lead to increased vulnerability and greater disconnection from healthcare [43] (CMO#17).

4. Final Programme Theory

The inter-relationships between these initial programme theories are illustrated below (Figure 4).

4.1. Communication Environment and Interpersonal Relations

The communication environment (CMO#9) is a cross-cutting contextual factor appearing in all contextual layers, highlighting its importance and relationship to telephone consulting. Examples at the individual level could include patients travelling or looking after children during the appointment, and for HCPs, interruptions or mobile phone pings or rings, influencing mechanisms of consultation conduct and experience for both patient and HCP and to a certain extent the patient–HCP relationship. It potentially hindered the openness and transparency necessary to fully assess a problem and affected the degree of privacy and confidentiality experienced.

However, a key consideration at the institutional layer impacting relationships with both HCPs and the service more generally is the sense of belonging (to the department) that recurrent service users feel when virtual follow-up is combined with face-to-face [37].

4.2. Individuals and Interpersonal Relationship Factors

Haemato-oncology and HSCT patients severely immunocompromised a contextual factor that requires specific consideration (CMO#15, 16, 17, 18). Interventions that support these highly vulnerable patients at risk of infection are important, although an approach that supports both telephone and in-person consultations seems necessary for safe, effective care.

For patients, factors such as distance from hospital and cost of appointments (travel, work and childcare) (CMO#10) were key drivers for telephone consultation even if health stability and their previous experiences of telephone consultation did not favour this approach. This leads to speculation that some patients prioritise finance above health even if this is not in their best interests.

Many patients are satisfied with telephone consultations, but the highly vulnerable and precarious state of health of patients with a haemato-oncological diagnosis means that even when being cared for at a distance, HCP access ‘on demand’ remains a priority. Therefore, when patients experience telephone consultations as a barrier to HCP availability or access (in-person or remotely) or their telephone consultation does not meet their needs, this mode is perceived less favourably (CMO#2).

Patient demographics such as age, education levels and hearing ability (CMO#4, 5, 7, 8) and the impact these contextual factors have on the effectiveness of telephone consultations is described in the synthesised literature; however, these also give rise to rival theories especially if appointment preparation and support are facilitated.

There are fewer contextual factors described that related to HCPs at an individual layer. That said, the literature supported that HCPs must be skilled, knowledgeable and experienced (CMO#13), but these contexts or attributes are not defined further.

The patient–HCP relationship is an important contextual factor within which the telephone consultation occurs and an established relationship or being known to the HCP increases patient trust, disclosure and leads to satisfaction (CMO#1). The context of HCP accessibility also appears to be associated with the HCP relationship context; more specifically, contact frequency, ease of contact and familiarity. This in turn impacts on experience and perceptions of telephone consulting from both the individual provider and recipient perspectives integrated within the interpersonal relationship layer.

4.3. Institutional (e.g., Organisational and Department Level Contexts) Factors

Institutional contexts incorporate the rules, norms and customs local to the programme where the intervention is delivered, and structural features of the consultation setting. Two factors aside from communication environment were reported in the synthesised literature: service resources (finance, infrastructure and staff) and institutional/departmental endorsement.

Service resources (finance, infrastructure, staff and training) (CMO#13) are powerful contexts that demonstrate the institutions’ regard for this intervention and is linked to institutional/departmental endorsement. Endorsement is critical to the availability of appropriate service resources. Without management and institutional support to embed and normalise telephone consulting, it is more likely to fail [36, 37].

4.4. Infrastructure (e.g., Government Policy, Political Support and Wider Setting) Factors

The wider social, economic and cultural setting, in which telemedicine is embedded, has several elements warranting attention. The communication environment and the level to which this is socially accepted are discussed by Kumar, Auret and Zomerdjik [36, 38, 40]. The telephone consultation implementation drivers seen in the current health policy highlight the readiness of governments nationally and internationally [2, 4, 5] to utilise telephone consulting to deliver health care at a lower cost while potentially improving access, convenience and choice for patients and as such make resources available to deliver this (CMO#13). While normalising remote provision of a whole range of health- and nonhealth-related services, the COVID-19 pandemic was an important contextual lever for people adapting to receiving care differently (CMO#15, CMO#19), normalising telephone consulting in a way not previously established.

Finally, the wider social and cultural setting offers potential implementation barriers particularly considering the COVID-19 pandemic and the health isolation experienced by many patients who were unable to access health care in an acceptable mode, if at all (CMO#17, CMO#18).

5. Discussion

This is the first realist synthesis of telemedicine using telephone consulting that has focused on its use in haemato-oncology. More research is needed and conclusions are tentative at present. The paucity of local and national studies means that evidence for this synthesis was drawn from global perspectives with natural variation in the context of these studies. It was not possible to explore variability across nations. This is an evolving area, and the study of variability across nations could be a focus for future work.

A final programme theory based on rigorous development and refinement of preliminary programme theories explains how, for whom and in which circumstances remote consultations via telemedicine for routine follow-up work for haemato-oncological and HSCT patients. The findings of this synthesis, in particular the final programme theory with its focus on the HCP–patient relationship and the contextual factors that make it effective, are generalisable to people with cancer more broadly and many other groups.

The programme theory offers an overview of the circumstances under which telephone follow-up triggers (or does not) mechanisms that generate or cause certain outcomes. Acknowledging the inter-relationships between the four contextual layers, of particular significance, is the HCP–patient relationship. This includes the contexts under which it is initiated (CMO#3) and sustained (CMO#1, CMO#2), and the importance of continuity (CMO#1) and ongoing HCP access (CMO#2) in sustaining that relationship. Much of Rowe and Calnan’s work focussed on trust as a cornerstone of effective HCP–patient relationships, and moreover, trust in healthcare organisations and systems [44]. However, they argue that changes in healthcare delivery have eroded organisational trust, while broader social and cultural processes have empowered patients to be more informed, can contest expert knowledge and may seek further opinion. Nonetheless, trust remains central and is reciprocal [44]; it is built upon communication and information provision and an HCP–patient relationship that is nurtured through clinician competence, respect, information sharing and confidence [45]. Finally, Sabety’s work explored the real worth of continuity and confirmed that patients value having a relationship with their HCP, and furthermore, this value increases over the length of the relationship (Sabety A 2023). Notably, greater effort is required to establish rapport and trust remotely than during face-to-face consultations, and remote consultations are enhanced if this rapport has been established prior to their use [46].

Key individual contextual factors found to be important in this review were patient age, hearing ability and cognitive ability [24, 37, 39], and the ‘institutional’ (structural) telephone consultation environment. These factors impact telephone consultation responses of trust, exchanging/providing information and overall confidence in telephone consultations themselves. Additionally, when telephone consultation is not suited to that patient’s personal contextual factors, the risk of missing important information is higher (CMO#6, CMO#7). These factors have also been reported in research in other areas such as primary care where this has been studied more extensively, and telephone consultations are shorter than face-to-face with fewer problems raised [47].

For many patients, contextual factors such as personal financial and time costs, impact on personal responsibilities and separation from their support network can be addressed through telephone consultations [36, 41]. This potentially addresses health disparity and inequality for some, but several risks exist including a shift to more transactional consultations, care quality (missed diagnoses, safeguarding challenges, more investigations and treatment) and increased patient responsibility more generally [14]. However, it is not clear in any of the literature, the extent to which these risks are understood by patients or if consultation choice would be influenced by appreciation of these risks.

While studies in the broader literature suggest that telephone consultation is acceptable to patients in a variety of circumstances [8, 20], issues relating to patient (and HCP) satisfaction warrant further exploration [9]. This synthesis identified the patient–HCP relationship (CMO#1), appointment rehearsal (CMO#8), health stability (CMO#12) and frequent routine monitoring (CMO#19) as contextual factors associated with telephone consultation satisfaction although greater knowledge and understanding of these contextual factors is required.

The COVID-19 pandemic led to a surge in investigations of remote consultation, though most COVID-19-related studies included were conducted during the initial 2020 wave [24, 38, 43] and thereby heavily influenced by patient and HCP reaction to access and healthcare provision at that time. They do not reflect the later mood of frustration at altered health systems, reduced numbers of in-person consultations and subsequent impact of perceived primary care access challenges on secondary and tertiary care [48].

Safety is particularly significant in haemato-oncology since these patients are vulnerable to symptomatic (and asymptomatic) health problems triggering in-person consultations to mitigate risks of missed or delayed diagnoses. Suitability of clinical environments for in-person consultation has become especially important since the COVID-19 pandemic [49]. This is an area of sensitivity described by the Patient and Public Involvement and Experience (PPIE) group during discussion with them at the outset of this work and corroborates [37] that remote consulting offers immunocompromised people a protective resource against nosocomial transmission and contributes to strong and sustained support for this modality. However, telephone consulting is not a panacea and may foster in-person consultation avoidance. Symptomatic patients needing investigation (CMO#16) and those with complex care needs will still require in-person reviews. Video consulting receives much attention in the literature especially in primary care, in many ways is comparable to telephone consulting (consultation length and number of complaints discussed) and is similarly rated by patients [47]. However, despite the investment in video consultation infrastructure, international uptake has been low compared to telephone consultations [50] with age, low income and poor digital literacy among the barriers cited [4].

The social impact of remote consultations, whereby patients (and their carers) are inadvertently disconnected from the social opportunities and routines that arise from in-person appointments [51], is an area not explicitly described in the reviewed literature and warrants further attention.

The synthesis highlights the real value of further investigation to fully understand for whom telephone consultation works, why and under what contexts to achieve its intended outcomes. For some people and under some circumstances, using telephone for synchronous remote consultations has been transformative. However, to uncover the real potential of this intervention in all its glory, a much better understanding of this complex intervention, and the mechanisms that are activated across the various contexts, needs to be achieved.

6. Strengths and Limitations

The use of a realist approach (reported rigorously in line with published standards) [26] is a strength because unlike previous reviews it elucidates an otherwise disparate body of literature and evidence, understands how context impacts and uses a range of data that might not be considered suitable in a conventional systematic review.

Remote consultations are not new, originating decades ago to provide a more practical follow-up solution for those in rural communities, but research undertaken in the specific area of haemato-oncology were sparse until recently providing limited empirical evidence to support generative causation (to develop CMOs and programme theory).

Study selection was the sole responsibility of the lead author and although not imperative for a realist review, the inclusion of a second reviewer in the identification of empirical evidence may have ensured consistency in approach.

This synthesis includes four studies reporting both telephone and video consultations. These contribute important data (CMOs) that are specified in the papers as relating to telephone consultations only or to telemedicine (both telephone and video) generally. There are no data relating to video consultations alone and the data from these studies are consistent with and support findings from telephone only interventions.

Elements of some of the CMOs were built from evidence-inspired data and hypothesised in line with realist methods [29], rather than directly from empirical data due to them lacking in the latter which is a further limitation.

The landscape of remote consultations is still emerging in postpandemic healthcare systems. Telemedicine technology is constantly evolving, but most synchronous telemedicine interventions in the United Kingdom are still conducted using audio only, not video (10, 12). Therefore, a strength of the body of literature spanning over two decades, included in this review, is that it remains largely relevant today.

7. Conclusion

This is the first realist synthesis of the literature regarding telemedicine using telephone for remote consultations in haemato-oncology. The synthesis has highlighted contextual factors at different levels or layers impacting on how and for whom telemedicine works. Evidence is lacking in relation to some specific contextual factors and their impact on whether/how telemedicine and more specifically telephone consultations work. This includes populations that are harder to reach, are vulnerable or experience health inequalities and should be the focus for future research. The findings of this synthesis, whilst being highly relevant for haemato-oncological care, may be generalisable to other groups including other cancer populations. Furthermore, the findings are apt to address sustainability needs of NHS services and infrastructure while optimising telephone consultation use to ensure patient and clinician satisfaction and safety.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

There is no funding received for this manuscript.

Supporting Information

Supporting file S1: Realist synthesis data extraction example (Supporting Information).

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.