Factors Influencing Overall Survival Period of Stage IV Cancer Patients

Abstract

Objective: Research has been conducted worldwide from the perspective of data detection in the hope of understanding the factors influencing the survival of stage IV cancer patients. However, the majority of existing research has only focused on single influencing variables. We collected the basic information, cancer type, sites of metastasis, performance status, pain, comorbidities, and relevant laboratory test data of inpatients with stage IV cancer to conduct a comprehensive assessment of the factors influencing survival period.

Methods: A cohort study design was adopted, in which data were collected from the medical records of stage IV cancer patients undergoing cancer treatment at a teaching hospital in Northern Taiwan from January 2018 to December 2022.

Results: Data were collected from the medical records of 739 stage IV cancer patients, among whom 488 patients passed away. The mortality risks of patients who had gastric or esophageal cancer and those who had hepatic cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, or pancreatic cancer were higher than those who had head and neck cancer. Furthermore, the mortality risks were higher for those with a body mass index (BMI) < 25 kg/m2, liver metastases, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status scores of 2 or higher, and peptic ulcers. Regarding blood test values, the mortality risks of stage IV cancer patients with albumin < 3.5 g/dL, hemoglobin (Hgb) < 10.0 gm/dL, and C-reactive protein (CRP) ≥ 10.0 gm/dL were also higher.

Conclusions: Cancer stage and metastasis conditions are beyond their control; however, effort can be devoted to maintaining the BMI and performance status of stage IV cancer patients, treating their peptic ulcers, and monitoring their albumin, Hgb, and CRP levels. These variables can serve as a reference for medical personnel in care decisions regarding stage IV cancer patients.

1. Introduction

Stage IV is the most severe stage of cancer where the cancer has metastasized to different parts of the body. Though it has the highest risk of mortality, it is not necessarily terminal [1]. With advancements in medical technology, new treatment methods introduced in recent years, such as novel chemotherapies as well as targeted drugs and immunotherapy, can effectively lengthen the survival period of stage IV cancer patients and enable them to live with their cancer [2]. At present, the medical community is divided on what factors affect the survival of stage IV cancer patients [3]; however, the most frequently asked question by patients and their family members is regarding the length of survival periods [1].

A number of factors may influence the predicted life expectancy of stage IV cancer patients. Demographic characteristics, such as gender, age, or body mass index (BMI), may be associated with survival. For instance, among patients with stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer, prognoses are much better for female patients than for male patients [4]; older cancer patients tend to have shorter survival periods [5, 6], and Tu et al. [7] noted that although being overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2) or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) increases the general risk of contracting cancer, it could in fact lengthen the survival period of patients.

Clinical care teams believe that the survival rate of stage IV cancer patients is linked to cancer type. For example, the five-year survival rate is 30% for breast cancer patients with distant metastasis but only 3% for small-cell lung cancer patients [8]. Some researchers have reported that the site to which the cancer has metastasized is the most crucial factor impacting cancer patient survival [9]. Other studies have indicated that the survival period of patients with aggressive cancer can only be accurately predicted based on the performance status or pain of the patients [10, 11]. It is common for cancer patients to simultaneously suffer from chronic diseases, and some studies have shown that these comorbidities are connected to the mortality of stage IV cancer patients [12, 13].

In another aspect, correlations also exist between clinical laboratory test data and the survival of stage IV cancer patients. For instance, a study conducted by Ju and Ma [14] on 1655 aggressive cancer patients undergoing treatment revealed that high C-reactive protein (CRP) to albumin ratios could be used as a predictor of their survival prognoses within 30 days. Anemia is also fairly common among stage IV cancer patients and has a significant and negative impact on survival [15, 16].

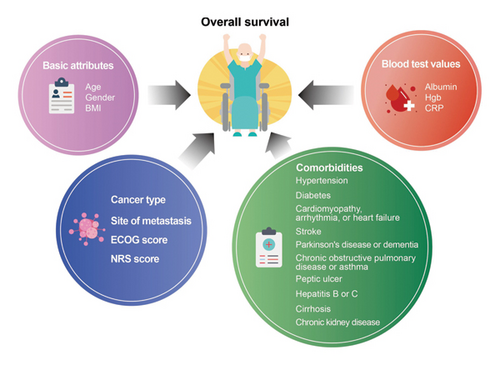

The majority of the existing research on the survival periods of stage IV cancer patients has focused on single influencing variables. We therefore collected the basic information, cancer type, sites of metastasis, performance status, pain, comorbidities, and relevant laboratory test data of inpatients with stage IV cancer to conduct a comprehensive assessment of the factors that influence the survival period. Furthermore, this should provide a valid basis for medical teams to assess the survival periods of stage IV cancer patients. We also compiled relevant literature and established the framework of this study (Figure 1).

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Samples

We adopted a cohort study design and collected data from the medical records at a large-scale teaching hospital in Northern Taiwan during a five-year period from January 2018 to December 2022. Our targets were conscious hospitalized stage IV cancer patients over the age of 18 undergoing cancer treatment (their main admission diagnosis was confirmed as stage IV cancer). The follow-up duration (in months) began from the day of their admission. Patients who had nonsolid malignant tumors, were diagnosed with more than one type of primary malignant tumor, or were lost to follow-up due to discharge or transfer (and whose exact time of death was unknown) were excluded from our analysis. Thus, 739 stage IV cancer patients were tracked. The period from the day of their admission to the date of their last outpatient visit or death served as a reference for the calculation of survival period.

2.2. Measures

- 1.

Cancer-related research defines patients who are 65 years old or above as elderly [17, 18]. Accordingly, we divided the patients into two age groups for analysis: < 65 years old and ≥ 65 years old.

- 2.

BMI is a person’s weight (kg) divided by the square of their height (m). Based on cancer-related research, we divided the patients into two BMI groups for analysis: < 25 kg/m2 and ≥ 25 kg/m2 [7, 19].

- 3.

We used ECOG scores, which range from 0 to 5, to evaluate the performance status of the patients (0 means physically normal and able to engage in predisease work activities without restriction; 1 means restricted in physically strenuous activity but able to carry out light work activities; 2 means ambulatory, capable of self-care, and not confined to a bed or chair for more than 50% of waking hours, but unable to carry out any work activities; 3 means capable of only some self-care and confined to a bed or chair for more than 50% of waking hours; 4 means completely disabled and confined to a bed or chair and incapable of self-care; and 5 means deceased). Patients with ECOG ≥ 3 are considered to have poor performance status, and those with ECOG ≤ 2 are considered to have good performance status. Clinically, this standard is widely used to assess the physical capacity of cancer patients and determine whether they can continue receiving treatment [20, 21]. We therefore divided the patients into three ECOG score groups for analysis: 0-1, 2, and 3 or higher.

- 4.

Pain was rated using the NRS, which is a 10-cm horizontal line with 11 points marked 0 on the very left, which indicates no pain, and 10 on the very right, indicating severe pain. The higher the number, the greater the intensity of pain. As suggested in cancer-related research, we divided the patients into three NRS score groups for comparison: no/very mild pain (NRS scores 0–3), moderate pain (NRS scores 4–6), and extreme/very severe pain (NRS scores 7–10) [22].

- 5.

The blood test items included albumin, Hgb, and CRP. The normal reference range for albumin is 3.5–5.5 g/dL. As suggested in another study, we used 3.5 g/dL as the cutoff point for albumin [23]. The normal reference values for Hgb differ slightly depending on gender: male adults, 13.0–18.0 g/dL; and female adults, 11.0–16.0 g/dL. The World Health Organization and the National Cancer Institute of the US define anemia using Hgb [24]. Hgb levels of 10 g/dL are the lower limit of the normal range and indicate mild anemia; Hgb levels of 8.0–9.9 g/dL indicate moderate anemia; and Hgb levels below 8 g/dL indicate severe and life-threatening anemia [25]. We used 10 g/dL as the cutoff point for our statistics. Furthermore, although CRP is not a marker specific to cancer, it may rise in cancer patients and is clinically relevant in determining prognoses [26]. As suggested by studies regarding cancer and the guidelines of the US Food and Drug Administration on care for inflammatory diseases, we used 10 μg/mL as the cutoff point for CRP [27, 28].

2.3. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Taipei Medical University-Joint Institutional Review Board (TMU-Joint IRB) before data collection began. It was ensured that the personnel participating in this study would never disclose any personal or private information. The patients whose medical records that we reviewed were all cases that received routine treatments. All treatments had been completed before this study was proposed; therefore, consent by the subjects was waived. All medical records and test data that were copied during this study were also de-identified to protect the rights of the patients and uphold research ethics.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows 21.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). We first used descriptive statistics to explain the distributions of the samples. All comparisons of the survivors and the deceased involved categorical variables and were thus analyzed using chi-squared tests. We then used the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and the Cox proportional hazard model to analyze survival and follow-up durations with personal attributes (including age, gender, and BMI), cancer-related variables (including cancer type, site of metastasis, ECOG score, and NRS score), comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy/cardiac dysrhythmia/heart failure, stroke, Parkinson’s disease or dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma, peptic ulcer, hepatitis B or C, cirrhosis, and chronic kidney disease), and blood test data (including albumin, Hgb, and CRP) as independent variables. To identify influence factors, the multivariate Cox proportional hazard model first selects variables that are significantly correlated with survival and follow-up duration using univariate analysis and subsequently analyzes the influence of these variables on survival and follow-up duration using a multivariate model. Those with p values less than 0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Attributes and Basic Information of Stage IV Cancer Patients

The median follow-up duration of the stage IV cancer patients in this study was 6.1 months (25%–75% IQR = 2.4–13.3). During the study period, a total of 488 patients passed away (overall survival 66.0%). The mean age of the patients was 62.45 ± 11.89 years old. Male patients, of whom there were 405, accounted for over half of the patients (54.8%). The majority of the patients had a senior high school degree or lower (80.8%). Most of the patients were married (75.4%). Among the patients, 68.5% were unemployed or retired, and 52.8% were religious. Their mean BMI was 22.72 ± 4.45 kg/m2. The most common cancer type among the patients was colorectal cancer, which 193 of the patients (26.1%) had. Head and neck cancers were the second most common cancers (18.5%). In terms of sites of metastasis, the most common sites were the pleura, pericardium, mesentery, or neck lymph nodes (55.2%), followed by the lungs (35.2%) and the liver (34.4%). Over half of the patients, i.e., 411 patients (55.6%), had ECOG scores of 0-1. The NRS score of the majority of the patients (547 patients, 74.0%) was 0–3. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (36.5%) and diabetes (24.5%). The mean albumin, Hgb, and CRP levels were 3.4 ± 0.65 g/dL, 10.8 ± 1.98 gm/dL, and 7.1 ± 7.61 μg/mL, respectively (Table 1).

| Feature | Population |

|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 62.45 ± 11.89 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 334 (45.2) |

| Male | 405 (54.8) |

| Educational background | |

| Senior high school or below | 597 (80.8) |

| Junior college or above | 142 (19.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 557 (75.4) |

| Single, divorced, or widowed | 182 (24.6) |

| Current state of employment | |

| Employed | 233 (31.5) |

| Unemployed or retired | 506 (68.5) |

| Religious | |

| Yes | 390 (52.8) |

| No | 349 (47.2) |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 22.72 ± 4.45 |

| Cancer type, n (%) | |

| Head and neck cancer | 137 (18.5) |

| Colorectal cancer | 193 (26.1) |

| Breast cancer | 120 (16.2) |

| Genitourinary cancer | 55 (7.4) |

| Gastric or esophageal cancer | 97 (13.1) |

| Cholangiocarcinoma, hepatic or pancreatic cancer | 79 (10.7) |

| Lung cancer | 58 (7.8) |

| Site of metastasis, n (%) | |

| Bones | 225 (30.4) |

| Lungs | 260 (35.2) |

| Liver | 254 (34.4) |

| Brain | 67 (9.1) |

| Other (pleura, pericardium, mesentery, or neck lymph nodes) | 408 (55.2) |

| ECOG score, n (%) | |

| 0-1 | 411 (55.6) |

| 2 | 218 (29.5) |

| 3 or higher | 110 (14.9) |

| NRS score, n (%) | |

| 0–3 | 547 (74.0) |

| 4–6 | 178 (24.1) |

| 7–10 | 14 (1.9) |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | |

| Hypertension | 270 (36.5) |

| Diabetes | 181 (24.5) |

| Cardiomyopathy, arrhythmia, or heart failure | 95 (12.9) |

| Stroke | 40 (5.4) |

| Parkinson’s disease or dementia | 15 (2.0) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma | 18 (2.4) |

| Peptic ulcer | 64 (8.7) |

| Hepatitis B or C | 91 (12.3) |

| Cirrhosis | 25 (3.4) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 45 (6.1) |

| Blood test values | |

| Albumin, g/dL (mean ± SD) | 3.4 ± 0.65 |

| Hgb, gm/dL (mean ± SD) | 10.8 ± 1.98 |

| CRP, μg/mL (mean ± SD) | 7.1 ± 7.61 |

| Overall survivala (months), median (25%–75% IQR) | 6.1 (2.4–13.3) |

- Note: Hgb, hemoglobin; IQR, interquartile range.

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; SD, standard deviation.

- aOverall survival: The period between the day of patient admission and the date of their last outpatient visit or death served as a reference for the calculation of survival period.

3.2. Attributes and Clinical Basic Information of Survivors and Deceased Among Stage IV Cancer Patients

A comparison of the stage IV cancer patients divided into a survivor group and a deceased group revealed significant differences in age (p = 0.032), BMI (p = 0.033), liver metastases (p < 0.001), ECOG score (p < 0.001), and NRS score (p < 0.001) as well as comorbidities peptic ulcer (p < 0.001) and chronic kidney disease (p = 0.041). They also presented differences in albumin (p < 0.001), Hgb (p < 0.001), and CRP (p < 0.001) levels as well as in the overall survival of the patients (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

| Feature | Survivors n = 251 | Deceased n = 488 | pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age | 0.032 | ||

| ≤ 65 years old | 163 (64.9) | 277 (56.8) | |

| > 65 years old | 88 (35.1) | 211 (43.2) | |

| Gender | 0.386 | ||

| Female | 119 (47.4) | 215 (44.1) | |

| Male | 132 (52.6) | 273 (55.9) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.033 | ||

| < 25 kg/m2 | 177 (70.5) | 379 (77.7) | |

| ≥ 25 kg/m2 | 74 (29.5) | 109 (22.3) | |

| Cancer type | 0.268 | ||

| Head and neck cancer | 61 (24.3) | 76 (15.6) | |

| Colorectal cancer | 64 (25.5) | 129 (26.4) | |

| Breast cancer | 52 (20.7) | 68 (13.9) | |

| Genitourinary cancer | 10 (4.0) | 45 (9.2) | |

| Gastric or esophageal cancer | 24 (9.6) | 73 (15.0) | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma, hepatic or pancreatic cancer | 16 (6.4) | 63 (12.9) | |

| Lung cancer | 24 (9.6) | 34 (7.0) | |

| Site of metastasis | |||

| Bones | 68 (27.1) | 157 (32.2) | 0.155 |

| Lungs | 77 (30.7) | 183 (37.5) | 0.066 |

| Liver | 61 (24.3) | 193 (39.5) | < 0.001 |

| Brain | 20 (8.0) | 47 (9.6) | 0.456 |

| Other (pleura, pericardium, mesentery, or neck lymph nodes) | 134 (53.4) | 274 (56.1) | 0.475 |

| ECOG score | < 0.001 | ||

| 0-1 | 194 (77.3) | 217 (44.5) | |

| 2 | 45 (17.9) | 173 (35.5) | |

| 3 or higher | 12 (4.8) | 98 (20.1) | |

| NRS score | < 0.001 | ||

| 0–3 | 229 (91.2) | 318 (65.2) | |

| 4–6 | 21 (8.4) | 157 (32.2) | |

| 7–10 | 1 (0.4) | 13 (2.7) | |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Hypertension | 86 (34.3) | 184 (37.7) | 0.357 |

| Diabetes | 55 (21.9) | 126 (25.8) | 0.242 |

| Cardiomyopathy, arrhythmia, or heart failure | 30 (12.0) | 65 (13.3) | 0.599 |

| Stroke | 9 (3.6) | 31 (6.4) | 0.115 |

| Parkinson’s disease or dementia | 2 (0.8) | 13 (2.7) | 0.088 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma | 7 (2.8) | 11 (2.3) | 0.655 |

| Peptic ulcer | 7 (2.8) | 57 (11.7) | < 0.001 |

| Hepatitis B or C | 32 (12.7) | 59 (12.1) | 0.796 |

| Cirrhosis | 7 (2.8) | 18 (3.7) | 0.522 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 9 (3.6) | 36 (7.4) | 0.041 |

| Blood test values | |||

| Albumin | < 0.001 | ||

| < 3.5 g/dL | 48 (20.8) | 317 (66.9) | |

| ≥ 3.5 g/dL | 183 (79.2) | 157 (33.1) | |

| Hgb | < 0.001 | ||

| < 10.0 gm/dL | 33 (13.1) | 238 (48.8) | |

| ≥ 10.0 gm/dL | 218 (86.9) | 250 (51.2) | |

| CRP | < 0.001 | ||

| < 10.0 μg/mL | 149 (87.6) | 285 (68.0) | |

| ≥ 10.0 μg/mL | 21 (12.4) | 134 (32.0) | |

| Overall survivala (months), median (25%–75% IQR) | 14.6 (8.4–24.0) | 3.6 (1.6–7.3) | < 0.001 |

- Note: Hgb, hemoglobin; IQR, interquartile range.

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale.

- aCategorical variables were analyzed using chi-squared tests.

3.3. Risk Analysis of Survival Period of Stage IV Cancer Patients Using Univariate Factors

The univariate Cox regression analysis in Table 3 shows that the regression coefficients of age > 65 years old (HR = 1.37, p = 0.001), BMI < 25 kg/m2(HR = 1.37, p = 0.004), and cancer type being colorectal cancer (HR = 1.49, p = 0.006), genitourinary cancer (HR = 2.13, p < 0.001), gastric or esophageal cancer (HR = 1.96, p < 0.001), hepatic cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, or pancreatic cancer (HR = 2.48, p < 0.001) were significant. The regression coefficients of lung metastases (HR = 1.28, p = 0.008) and liver metastases (HR = 1.53, p < 0.001) were also significant. For ECOG scores, the regression coefficients of ECOG scores of 2 (HR = 2.24, p < 0.001) and 3 or higher (HR = 3.65, p < 0.001) were significant. Regarding NRS scores, the regression coefficients of NRS scores 4–6 (HR = 2.10, p < 0.001) and 7–10 (HR = 2.87, p < 0.001) were significant. The regression coefficients of the comorbidities stroke (HR = 1.48, p = 0.036) and peptic ulcer (HR = 1.96, p < 0.001) and those of the blood test values for albumin < 3.5 g/dL (HR = 3.66, p < 0.001), Hgb < 10.0 gm/dL (HR = 2.77, p < 0.001), and CRP≥ 10.0 μg/mL (HR = 2.04, p < 0.001) were also significant, thereby indicating clear associations between these variables and survival period. Thus, these variables were included in the multivariate model analysis.

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age > 65 years old (reference group: ≤ 65 years old) | 1.37 (1.15–1.64) | 0.001 | 1.00 (0.81–1.23) | 0.983 |

| Female (reference group: male) | 1.07 (0.90–1.28) | 0.438 | ||

| BMI < 25 kg/m2 (reference group: ≥ 25 kg/m2) | 1.37 (1.11–1.70) | 0.004 | 1.32 (1.04–1.69) | 0.023 |

| Cancer type (reference group: head and neck cancer) | ||||

| Colorectal cancer | 1.49 (1.12–1.99) | 0.006 | 1.20 (0.84–1.71) | 0.317 |

| Breast cancer | 1.09 (0.78–1.51) | 0.609 | 1.27 (0.87–1.86) | 0.213 |

| Genitourinary cancer | 2.13 (1.47–3.09) | < 0.001 | 1.40 (0.93–2.10) | 0.109 |

| Gastric or esophageal cancer | 1.96 (1.42–2.71) | < 0.001 | 1.66 (1.15–2.39) | 0.007 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma, hepatic or pancreatic cancer | 2.48 (1.77–3.49) | < 0.001 | 1.57 (1.05–2.35) | 0.030 |

| Lung cancer | 1.15 (0.77–1.73) | 0.498 | 1.10 (0.70–1.75) | 0.672 |

| Site of metastasis | ||||

| Bones | 1.14 (0.94–1.38) | 0.180 | ||

| Lungs | 1.28 (1.07–1.54) | 0.008 | 1.07 (0.86–1.32) | 0.558 |

| Liver | 1.53 (1.27–1.83) | < 0.001 | 1.56 (1.25–1.95) | < 0.001 |

| Brain | 1.05 (0.78–1.43) | 0.729 | ||

| Other | 0.93 (0.78–1.11) | 0.435 | ||

| ECOG score (reference group: 0-1) | ||||

| 2 | 2.24 (1.83–2.74) | < 0.001 | 1.95 (1.55–2.47) | < 0.001 |

| 3 or higher | 3.65 (2.86–4.65) | < 0.001 | 2.68 (2.01–3.58) | < 0.001 |

| NRS score (reference group: 0–3) | ||||

| 4–6 | 2.10 (1.73–2.55) | < 0.001 | 1.22 (0.98–1.51) | 0.079 |

| 7–10 | 2.87 (1.64–5.01) | < 0.001 | 1.36 (0.74–2.49) | 0.326 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Hypertension | 1.17 (0.97–1.40) | 0.097 | ||

| Diabetes | 1.20 (0.98–1.48) | 0.072 | ||

| Cardiomyopathy, arrhythmia, or heart failure | 1.15 (0.89–1.49) | 0.297 | ||

| Stroke | 1.48 (1.03–2.13) | 0.036 | 0.99 (0.65–1.53) | 0.978 |

| Parkinson’s disease or dementia | 1.59 (0.92–2.77) | 0.097 | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma | 0.81 (0.45–1.47) | 0.492 | ||

| Peptic ulcer | 1.96 (1.49–2.59) | < 0.001 | 1.59 (1.16–2.17) | 0.004 |

| Hepatitis B or C | 0.97 (0.74–1.27) | 0.800 | ||

| Cirrhosis | 1.37 (0.85–2.19) | 0.195 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.11 (0.79–1.56) | 0.551 | ||

| Blood test values | ||||

| Albumin < 3.5 g/dL | 3.66 (3.01–4.45) | < 0.001 | 1.99 (1.57–2.53) | < 0.001 |

| Hgb < 10.0 gm/dL | 2.77 (2.31–3.32) | < 0.001 | 1.99 (1.61–2.46) | < 0.001 |

| CRP ≥ 10.0 μg/mL | 2.04 (1.66–2.50) | < 0.001 | 1.28 (1.02–1.62) | 034 |

- Note: Hgb, hemoglobin; 95% CL, confidence limits at 95%.

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HR, hazard ratio; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale.

3.4. Predictors of Survival Period of Stage IV Cancer Patients

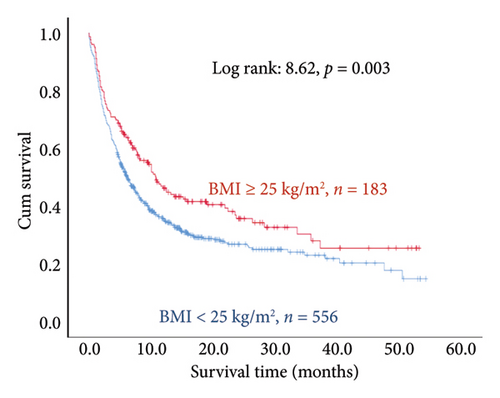

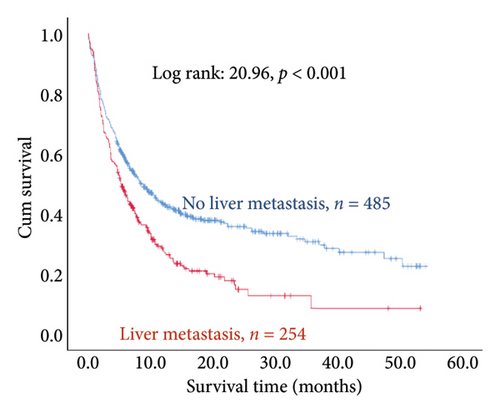

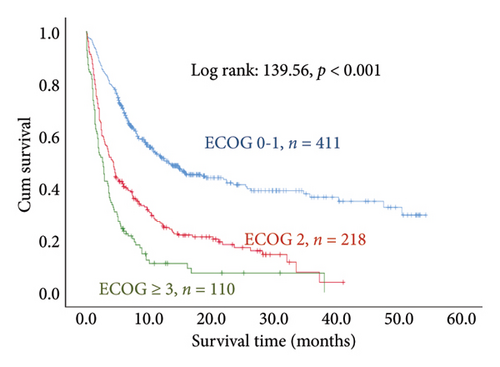

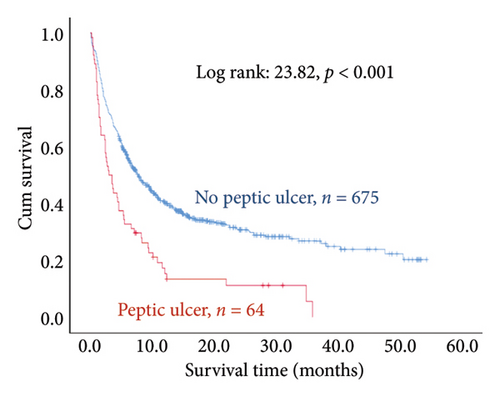

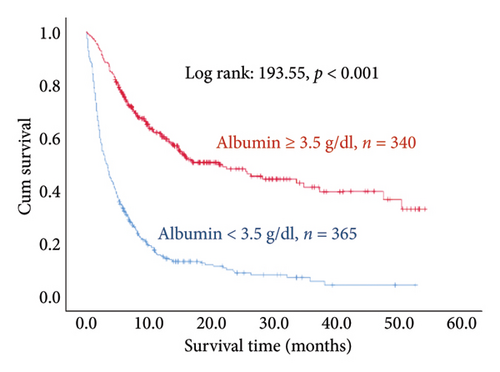

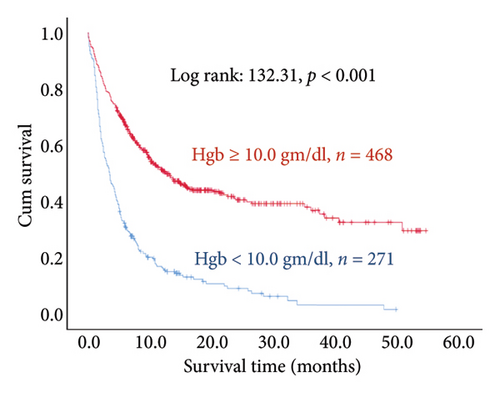

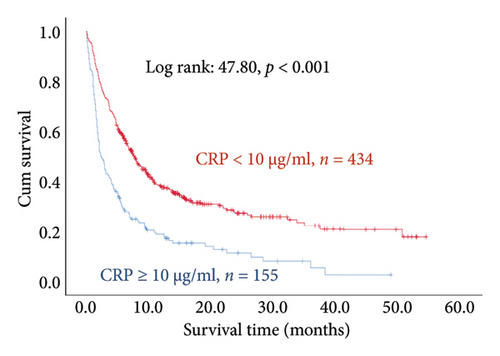

The results of the multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that the regression coefficient of BMI < 25 kg/m2 (HR = 1.32, p = 0.023) was significant. A Kaplan–Meier survival analysis also indicated that the survival periods of patients with BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 were longer than those of patients with BMI < 25 kg/m2 (log rank: 8.62, p = 0.003). In cancer type, the regression coefficients of gastric or esophageal cancer (HR = 1.66, p = 0.007) as well as hepatic cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, or pancreatic cancer (HR = 1.57, p = 0.030) were significant. For the site of metastasis, the regression coefficient of liver metastases (HR = 1.56, p < 0.001) was significant. A Kaplan–Meier survival analysis also indicated that the survival periods of patients with no liver metastases were longer than those of patients with liver metastases (log rank: 20.96, p < 0.001). Regarding ECOG scores, the regression coefficients of ECOG scores of 2 (HR = 1.95, p < 0.001) and 3 or higher (HR = 2.68, p < 0.001) were significant. A Kaplan–Meier survival analysis also showed that the survival periods of patients with ECOG scores of 0-1 were longer than those of patients with ECOG scores of 2 and those of patients with ECOG scores of 3 or higher (log rank: 139.56, p < 0.001). In comorbidities, the regression coefficient of peptic ulcer (HR = 1.59, p = 0.004) was significant, and a Kaplan–Meier survival analysis also revealed that the survival periods of patients with no peptic ulcers were longer than those of patients with peptic ulcers (log rank: 23.82, p < 0.001). For blood test values, the regression coefficient of albumin < 3.5 g/dL (HR = 1.99, p < 0.001) was significant, and a Kaplan–Meier survival analysis indicated that the survival periods of patients with albumin ≥ 3.5 g/dL were longer than those of patients with albumin < 3.5 g/dL (log rank: 193.55, p < 0.001); the regression coefficient of Hgb < 10.0 gm/dL (HR = 1.99, p < 0.001) was significant, and a Kaplan–Meier survival analysis indicated that the survival periods of patients with Hgb ≥ 10.0 gm/dL were longer than those of patients with Hgb < 10.0 gm/dL (log rank: 132.31, p < 0.001); the regression coefficient of CRP ≥ 10.0 μg/mL (HR = 1.28, p = 0.034) was significant, and a Kaplan–Meier survival analysis indicated that the survival periods of patients with CRP < 10.0 μg/mL were longer than those of patients with CRP ≥ 10.0 μg/mL (log rank: 47.80, p < 0.001) (Table 3 and Figure 2).

4. Discussion

The results demonstrate that the survival periods of stage IV cancer patients with BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 were significantly longer than those of stage IV cancer patients with BMI < 25 kg/m2. In cancer type, the mortality risks of patients who had stage IV gastric or esophageal cancer and those who had stage IV hepatic cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, or pancreatic cancer were higher than those who had stage IV head and neck cancer. Moreover, the mortality risk of patients with liver metastases was higher, and the mortality risks of patients with ECOG scores of 2 or higher were higher than those of patients with ECOG scores of 0-1. Furthermore, the mortality risks of stage IV cancer patients who had peptic ulcers were even higher. Regarding blood test values, the mortality risk of stage IV cancer patients with albumin < 3.5 g/dL was higher than that of stage IV cancer patients with albumin ≥ 3.5 g/dL; the mortality risk of stage IV cancer patients with Hgb < 10.0 gm/dL was higher than that of stage IV cancer patients with Hgb ≥ 10.0 gm/dL, and the mortality risk of stage IV cancer patients with CRP ≥ 10.0 gm/dL was higher than that of stage IV cancer patients with CRP < 10.0 gm/dL.

This study employed the Cox proportional hazard model to assess the influence of different cancer types on the survival of stage IV cancer patients. In this model, we regarded cancer type as an independent variable in consideration of the heterogeneity among different cancers [29]. Owing to our separate hazard analyses of colorectal cancer, breast cancer, genitourinary cancer, gastric or esophageal cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, hepatic or pancreatic cancer, and lung cancer, we discovered significant differences in the mortality risks of different cancers, indicating that the personal attributes of patients with different cancer types are already reflected in the cancer type variable. This analysis method enables the recognition of the heterogeneity among different cancers and furthers our understanding of the impact of cancer characteristics on patient survival.

Collet et al. [19] analyzed 272 patients with aggressive cancer. A Kaplan–Meier survival analysis that they conducted indicated that the survival periods of patients with BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 were significantly longer than those of patients with BMI < 25 kg/m2 (p = 0.015). A meta-analysis performed by Greenlee et al. [30] on 22 clinical trials also presented similar results; the authors believed that male patients with aggressive cancer and BMI < 25 kg/m2 have poorer prognoses and higher mortality risks. In support, the results of our study were also consistent: the mortality risk of stage IV cancer patients with BMI < 25 kg/m2 was 1.32 times higher than that of stage IV cancer patients with BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2. Indeed, evidence in existing research supports the notion that obesity caused by overeating can lead to antitumor effects by reducing the proportion of immature CD8+ T cells and increasing the size of bone marrow cells [31].

This study also found that the mortality risk of patients with stage IV gastric or esophageal cancer was higher than that of patients with stage IV head and neck cancer. Verstegen et al. [32] reported that over half of gastric or esophageal cancers had already metastasized by the time of diagnosis. Due to the high incidence of local recurrence and distant metastasis, the prognoses of gastric or esophageal cancer patients are generally poor. Similarly, the prognoses of liver cancer patients are also poor, and cholangiocarcinoma and pancreatic cancer are even bigger medical challenges at present because these cancers are more difficult to diagnose and treat than other cancers [33–35]. Pancreatic cancer, in particular, is widely recognized as one of the most lethal types of cancer; the 5-year survival rate of stage IV pancreatic cancer is only 2.9% [36]. In contrast, a large-scale database study indicated that although the mortality risk of patients with head and neck cancer is 7.72 times higher than that of individuals of the same age and gender with no cancer, the mortality risk of patients with other types of cancer is 8.87 times higher than that of individuals of the same age and gender with no cancer, thereby proving that the mortality risk of patients with head and neck cancer is lower than those of patients with other types of cancer [37].

We found in our study that patients with liver metastases had a higher mortality risk. Other studies have also demonstrated that cancer metastasis to the liver increases the risk of mortality compared to metastasis to other locations. A large-scale database cohort study conducted by Wang et al. [38] found that among 1.6 million cancer patients, liver metastases were present in 6.46% of these patients, and the median survival period of these patients was only 4 months. Similarly, Li et al. [39] investigated the prognoses of lung cancer patients whose cancer had metastasized to different sites and discovered that among all patients with distant metastasis, those with liver metastases had the shortest survival periods.

This study considered and included pre-existing conditions in the multivariate analysis model. For instance, peptic ulcers were listed as a risk factor, and our analysis demonstrated that they were significantly correlated with survival. Although this study did not examine previous cancer treatments (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or immunotherapy) in detail, it emphasizes the impact of physical condition (ECOG score) and physiological indices (albumin, Hgb, and CRP), which play key roles in clinical decisions. The ECOG score is generally used to assess the physical capacity of patients; higher scores indicate poorer physical conditions and are associated with poorer prognoses [40]. Albumin, Hgb, and CRP provide information on the nutritional, inflammatory, and anemic conditions of patients, which are also closely associated with patient survival [14, 41] due to their direct reflection of a patient’s overall health and tolerance to treatment. These clinical indices can not only help medical teams to evaluate the health status of terminal cancer patients but also serve as decision aids for the selection and adjustment of palliative care plans.

An early research study by Walsh et al. [42] indicated a connection between the performance status and survival period of aggressive cancer patients; they found that for each one-point increase in the ECOG score, the mortality risk of the patient increases by 1.4 times. Recent research has identified similar findings, making the ECOG score a crucial factor in predicting the survival period of patients with aggressive cancer [43]. We analyzed the performance status of stage IV cancer patients and similarly found that their mortality risk is higher in patients who have an ECOG score of 2 or 3 or higher compared to patients with an ECOG score of 0-1.

We further discovered that stage IV cancer patients with peptic ulcers as a comorbidity had a 1.59 times higher mortality risk compared to patients without peptic ulcers. Furthermore, cancer patients may also succumb to noncancer causes. For instance, radiotherapy and chemotherapy are routine treatments for patients with unresectable cancer. However, these treatments are also toxic and can damage the gastrointestinal tract, making peptic ulcers a common problem. Peptic ulcers are a chronic progressive disease resulting from damaged gastrointestinal mucosa in which the protective effect is diminished. Complications such as erosion, bleeding, and perforation can lead to patient death [44]. Yang et al. [45] investigated the mortality rate of cancer patients with peptic ulcers and found that 4698 out of 8.4 million cancer patients died of peptic ulcers and that their mortality risk was 1.78 times higher than that of peptic ulcer patients with no cancer. The mortality risk of cancer patients with distant metastasis as well as peptic ulcers was even higher: 3.40 times higher compared to peptic ulcer patients without cancer.

In another aspect, researchers have presented strong evidence that albumin is an acute phase reactant of inflammation. Overly low levels of albumin in patients are a strong indication of cachexia [46, 47]; on the other hand, increases in albumin can hinder the progression of cancer cachexia and inflammation. We analyzed the albumin levels in stage IV cancer patients and found that cancer patients with albumin levels below 3.5 g/dL had higher mortality risks than those with albumin levels of 3.5 g/dL or higher. Viganò et al. [48] discovered that albumin levels below 3.5 g/dL are a crucial predictor of whether the patients could survive past the median survival time of 15.3 weeks.

In this study, the mortality risk of stage IV cancer patients with Hgb levels below 10.0 gm/dL was higher than that of stage IV cancer patients with Hgb levels at 10.0 gm/dL or higher. A systematic review based on two hundred papers conducted by Caro et al. [49] similarly indicated that anemia increases the relative mortality risk of cancer patients: anemia increases mortality risk by 19% in lung cancer patients, by 75% in head and neck cancer patients, by 47% in prostate cancer patients, and by 67% in lymphoma patients. Overall, anemia increases the risk of mortality by 65% in cancer patients.

When stimulated by interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α, liver cells synthesize increasing levels of CRP. Past research has shown that CRP is an independent factor that can be used to predict the survival time of late-stage cancer patients [50]. A study conducted by Stone et al. [51] found that increases in CRP are a significant predictor of whether patients can survive past the median of 14 days. Hart et al. [27] pointed out that CRP has unique properties in the development of prometastatic tumor microenvironments. In recent years, researchers have demonstrated that the CRP/albumin ratio can be used to effectively predict the prognoses of late-stage cancer patients [52, 53]. Recent studies have also indicated that ECOG scores and CRP/albumin ratios can both independently predict the survival period of late-stage cancer patients and that together, unfavorable values have a synergistic effect that accelerates the death of late-stage cancer patients [54]. This is consistent with the results of this study, in which a higher mortality risk was found in cancer patients with CRP levels of 10.0 gm/dL or higher.

4.1. Implications for Practice

For medical teams, cancer stage and metastasis conditions are out of their control; however, effort should be devoted to maintaining a healthy BMI and performance status of stage IV cancer patients, treating their peptic ulcers, and monitoring their albumin, Hgb, and CRP levels. For instance, medical teams must pay even closer attention to improving the nutritional status and physical conditions of stage IV cancer patients with a BMI below 25 and more proactively control the ulcer conditions of stage IV cancer patients with peptic ulcers in order to reduce their mortality risk. Clinically, additional nutritional support, treatments to improve anemia such as blood transfusions, or assessments of the source of inflammation and subsequent active measures should, respectively, be considered for stage IV cancer patients with albumin lower than 3.5 g/dL, Hgb lower than 10.0 gm/dL, or CRP higher than 10.0 μg/mL to improve their survival and quality of life.

4.2. Conclusion

This study examined 739 stage IV cancer patients for 6.1 months. The results showed that the overall mortality rate was 66.0% and that the mortality risks of gastric or esophageal cancer as well as hepatic cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, or pancreatic cancer were higher than that of head and neck cancer. Patients with BMI < 25 kg/m2, liver metastases, poor performance status, and peptic ulcers as a comorbidity also had a greater mortality risk. With regard to blood test values, we found a higher mortality risk in stage IV cancer patients with albumin < 3.5 g/dL, Hgb < 10.0 gm/dL, and CRP ≥ 10.0 gm/dL.

This study is unique in its comprehensive consideration of multiple variables that impact the survival of stage IV cancer patients, simultaneously taking into account demographic characteristics, cancer type and site of metastasis, physical conditions, pain conditions, comorbidities, and laboratory blood test data. We employed the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and Cox proportional hazard model to comprehensively assess the influence of different factors on survival, and these methods are more extensive than single-variable studies. Furthermore, this study demonstrated the predictive value of blood test data (albumin, Hgb, and CRP) for the survival of stage IV cancer patients, which has been underreported in other studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors have nothing to report.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.