Work Participation of Patients Affected by Advanced Cancer: A Scoping Review of Current Knowledge

Abstract

Introduction: The increasing survival rates among patients with advanced cancer have brought attention to the issue of work participation for working-age individuals, while current studies predominantly focus on early-stage cancer patients. The objective of this scoping review was to summarize the current knowledge regarding the work participation of patients diagnosed with advanced-stage cancer.

Methods: A scoping review was conducted following Mak and Thomas’s guidelines and adhering to PRISMA-ScR standards. Three databases (PubMed, Web of Science, and PsycINFO) were systematically searched for articles published up to December 2023. An update was performed in September 2024. We included English and French studies on patients with advanced cancer, aged 18 years and over, with a focus on their work participation. The results are presented according to the arena model, which provides a framework for understanding different dimensions of work participation.

Results: Ten studies, primarily focusing on breast cancer, were included after screening 239 records. Key findings revealed that older women and certain ethnic groups face greater challenges in maintaining employment, with treatment side effects such as pain, fatigue, and cognitive impairment having a significant impact on work participation. The research emphasized the need for improved support and information from the healthcare system regarding employment issues.

Conclusion: This scoping review addresses the challenges of work participation for patients with advanced cancer, identifying personal, psychological, and workplace barriers. It emphasizes the need for tailored interventions and highlights a significant gap in healthcare professionals’ guidance on employment issues. Expanding research beyond breast cancer is essential to improve work participation for this population. The predominance of breast cancer in the current literature underscores the urgent need for broader research that includes a wider range of tumor types and male patients, in order to ensure that work participation strategies are inclusive and equitable.

1. Introduction

With the increasing survival rates among cancer patients [1], the employment status of working-age patients has emerged as a significant public health concern in the past 2 decades [2]. Since the side effects of the disease and its treatments, such as chemotherapy and hormone therapy, can last for many years [3], achieving a sustainable return to work (RTW) can be a complex challenge, creating uncertainty for cancer survivors, healthcare professionals, and employers [4]. While holistic approaches are currently proposed [5], they primarily target patients diagnosed with early-stage cancer, who have a favorable prognosis for recovery and a lower likelihood of relapse [6]. Notably, much of this research has focused on breast cancer, reflecting its high prevalence among women of working age and its prominent visibility in public health discourse [7]. A current trend is to extend observational research on the work participation of patients diagnosed with advanced cancer [8].

The term “advanced cancer” is generally used to describe cancers that cannot be cured [9]. It encompasses several different types of cancer: metastatic cancers, which include not only cancer cells that have spread throughout the body but also certain localized or locally advanced cancers that cannot be cured [10]. In all these cases, the aim of the treatment is to control the progression of the cancer pathology, i.e., to prevent further proliferation of cancer cells, or even to reduce their number [11]. The aim is therefore to slow down the progression of the disease and make it chronic.

The therapeutic landscape for managing patients diagnosed with an advanced cancer has also evolved in recent decades [12]. These medical advances have not only extended their life expectancy but have also resulted in longer treatment periods, which vary depending on the efficacy and tolerability of the treatment [13]. Patients diagnosed with advanced cancer also face a higher risk of relapse or lack of response to treatment, requiring treatment throughout their lives or alternating periods of treatment-free living with active surveillance and hospital care [14]. For working-age patients, work participation can significantly contribute to psychological and social well-being [15]. Consequently, recent studies have been proposed to gain a better understanding of the barriers and facilitators to work participation in advanced cancer patients [8]. However, it is probable that a significant amount of observational research will be replicated to eventually yield outcomes akin to those attained in studies involving patients diagnosed with early-stage cancer. We propose a scoping review on the findings focusing on work resumption and retention of patients diagnosed with advanced cancer.

2. Methods

A scoping review was conducted according to the guidelines proposed by Mak and Thomas [16]. Reporting has been performed in accordance with the guidelines for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [17]. The scoping review protocol was drafted a priori by the first and second authors (PG and SJ) and approved by the research team.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria were defined by the first, second, and last authors (PG, SJ, and BP). Studies were eligible if they (i) were written in English or French; (ii) included advanced cancer patients over 18 years of age; (iii) focused on the patients’ work participation (i.e., work status, RTW, or work retention); (iv) adopted an interventional or observational design; and (iv) used a qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-method design. Studies were excluded if (i) they did not correspond to the inclusion criteria, (ii) were identified as gray literature (e.g., thesis, conference abstracts, and books), (iii) were published as literature reviews (e.g., systematic and scoping reviews) or meta-analysis or meta-synthesis, or (iv) were published as research protocols.

2.2. Search Strategy

- •

PubMed (MEDLINE): (((“cancer∗” [Title] OR “carcinoma” [Title] OR “neoplasm” [Title] OR “tumor∗” [Title]) AND (“advanced” [Title] OR “metastas∗” [Title] OR “metastat∗” [Title])) AND (“return to work” [Title] OR “back to work” [Title] OR “work resumption” [Title] OR “work retention” [Title] OR “job retention” [Title] OR “occupational” [Title] OR “work participation” [Title] OR “employment” [Title] OR “work ability” [Title] OR “work” [Title] OR “job” [Title])) NOT (“occupational exposure∗” [Title]).

- •

Web of Science: (((TI = (“cancer∗” OR “carcinoma” OR “neoplasm” OR “tumor∗”)) AND TI = (“advanced” OR “metastas∗” OR “metastat∗”)) AND TI = (“return to work” OR “back to work” OR “work resumption” OR “work retention” OR “job retention” OR “occupational” OR “work participation” OR “employment” OR “work ability” OR “work” OR “job”)) NOT TI = (“occupational exposure∗”).

- •

PsycINFO (EBSCOhost): TI (“cancer” OR “carcinoma” OR “neoplasm” OR “tumor”) AND TI (“advanced” OR “metastas∗” OR “metastat∗”) AND TI (“return to work” OR “back to work” OR “work resumption” OR “work retention” OR “job retention” OR “occupational” OR “work participation” OR “employment” OR “work ability” OR “work” OR “job”) NOT TI “occupational exposure”.

2.3. Study Collection

The articles identified through the database search were first imported into Zotero (https://www.zotero.org). After eliminating duplicates, the article selection process consisted of two stages: (i) title/abstract screening and (ii) full-text selection. During Stage 1 (title/abstract screening), two authors (PG and SJ) independently conducted the screening and subsequently compared their respective lists of selected articles. In the event of disagreement, a discussion was initiated, and if necessary, a third author (BP) was consulted to reach a final decision. Stage 2 (full-text selection) followed the same process as Stage 1, involving the same authors (PG, SJ, and BP). The same process has been put in place to select additional papers after the update.

2.4. Study Analysis

After selecting the articles and extracting the data of interest, we decided to organize the results according to Loisel’s arena model, as it is well utilized to describe the overview of work participation of cancer survivors [18]. It considers that the problem in question must be approached in a global social context, which includes four facets: the personal system/coping, the healthcare system, the workplace system, and the legal and insurance system.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

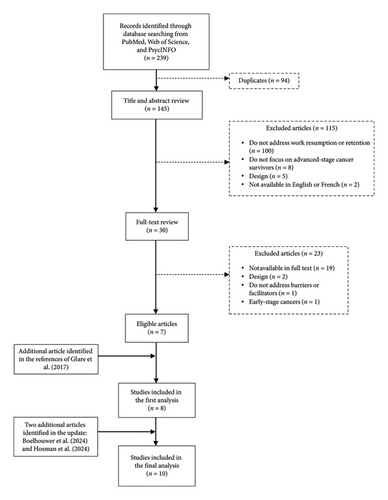

The search identified 239 references, of which 94 were duplicates, leaving 145 titles and abstracts to be screened. A total of 115 records did not meet the inclusion criteria, leaving 30 papers for full-text review. Of those, a further 23 articles were excluded, leaving seven studies for final analysis. Finally, we sifted through the references of these seven studies to make sure we had not missed one or more important articles. Through this process, we identified one additional article of interest. An update was carried out on September 30, 2024, and identified two new articles corresponding to our inclusion criteria. In total, we therefore included 10 articles in the analysis (Figure 1).

3.2. Study Characteristics

The topic of work resumption and retention in advanced cancer patients is relatively recent. Indeed, the first article identified dates back to 2014, and only nine other articles have been published since. Most studies have been carried out in the United States and are quantitative in nature. Finally, the most studied population corresponds to women with breast cancer (Table 1).

| n (/10) | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Year of publication | ||

| 2014 | 1 | Cleeland et al. [19] |

| 2016 | 1 | Tevaarwerk et al. [20] |

| 2017 | 1 | Glare et al. [21] |

| 2019 | 1 | Lyons et al. [22] |

| 2020 | 1 | Samuel et al. [23] |

| 2022 | 2 | Beerda et al. [24], Sesto et al. [25] |

| 2023 | 1 | Johnsson et al. [26] |

| 2024 | 2 | Boelhouwer et al. [27], Hosman et al. [28] |

| Country | ||

| The United States of America | 6 | Cleeland et al. [19], Glare et al. [21], Lyons et al. [22], Samuel et al. [23], Sesto et al. [25], Tevaarwerk et al. [20] |

| The Netherlands | 3 | Beerda et al. [24], Boelhouwer et al. [27], Hosman et al. [28] |

| Sweden | 1 | Johnsson et al. [26] |

| Methods | ||

| Quantitative | 8 | Boelhouwer et al. [27], Cleeland et al. [27], Glare et al. [21], Hosman et al. [28], Johnsson et al. [26], Lyons et al. [22], Samuel et al. [23], Tevaarwerk et al. [20] |

| Qualitative | 1 | Beerda et al. [24] |

| Mixed methods | 1 | Sesto et al. [25] |

| Design | ||

| Observational | 9 | Beerda et al. [24], Boelhouwer et al. [27], Cleeland et al. [27], Glare et al. [21], Johnsson et al. [26], Lyons et al. [22], Samuel et al. [23], Sesto et al. [25], Tevaarwerk et al. [20] |

| Interventional | 1 | Hosman et al. [28] |

| Population | ||

| Advanced breast cancer patients | 5 | Cleeland et al. [19], Johnsson et al. [26], Lyons et al. [22], Samuel et al. [23], Sesto et al. [25] |

| All types of advanced cancer patients | 5 | Beerda et al. [24], Boelhouwer et al. [27], Glare et al. [21], Hosman et al. [28], Tevaarwerk et al. [20] |

3.3. Main Results

Table 2 summarizes the main barriers and facilitators to work resumption and retention in advanced cancer patients.

| Authors | Focus | Participants | Outcome(s) | Identified barriers | Identified facilitators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beerda et al. [24] | Experiences and perspectives regarding work resumption and retention |

|

|

|

|

| Boelhouwer et al. [27] | Psychological capital and work functioning of workers with recurrent or metastatic cancer beyond return to work |

|

|

• Work ability is significantly lower among workers with cancer recurrence or metastases (controlling for age) | • A higher level of hope is positively associated with work ability and work engagement |

| Cleeland et al. [19] | Correlations between symptom burden and perception of activity and work impairment |

|

|

|

|

| Glare et al. [21] | Perspectives on the work–life, changes in work status, and predictors of remaining in employment |

|

• Work status |

|

|

| Hosman et al. [28] | Outcomes and feasibility of an occupational care programme (TERRA) to support the work ability of rare and advanced cancer patients |

|

|

• Problems at work, causing stress |

|

| Johnsson et al. [26] | Extent of RTW, demographic and tumor-related factors that influenced RTW, and impact of contemporary oncological treatment on RTW |

|

• Return to work for more than 90 and 180 WND, during the year after diagnosis | • Age ≤ 50 (aOR = 1.54; 95% CI: 1.35–1.84) | |

| Lyons et al. [22] | Associations of demographic, clinical, and cancer-related characteristics with patients’ continued employment, distress regarding vocational limitations, and interest in receiving help to re-enter the workforce |

|

|

|

• Physical exercise (OR = 4.7; p = 0.014) |

| Samuel et al. [23] | Ethnic differences in cancer-related changes in work for pay and cost-management behaviors |

|

|

• Other ethnicity than non-Hispanic White | |

| Sesto et al. [25] | Work status and information needs, importance of work, including motivations impacting work-related decisions |

|

|

|

|

| Tevaarwerk et al. [20] | Overall employment patterns and factors associated with stable employment versus a change to no longer working |

|

• Employment status and stability |

|

• Hormonal treatment (OR = 0.2; p = 0.03) |

- Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; aOR adjusted odds-ratios; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; OR, odds-ratios; RTW, return to work; WND, working net days.

We began by presenting the main outcomes and then detailed the results according to the different facets of the arena model (personal, healthcare, workplace, and legislative and insurance systems). Finally, we discussed the only interventional study.

3.3.1. Outcomes

Seven studies, five quantitative [20–23, 26], one qualitative [24], and one mixed [25], looked at the changes in occupational status between diagnosis and the time of the study. Three studies, one mixed [25] and two quantitative [27, 28], focused on work ability. In addition, one quantitative study described work productivity [19], and one quantitative study examined burnout complaints and work engagement [27].

3.3.2. Personal System and Personal Coping

The five studies that focused on sociodemographic criteria indicated that younger women were more likely to be employed than older women [22, 25, 26], and that in the United States of America, other ethnic groups (non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Asian, and American Indian) were more likely than non-Hispanic White patients with advanced cancer to report adverse changes in their employment status (reduction in hours and unpaid leave) [23] or to stop working [20].

“Whether I’m at home or at work, the pain is there anyway. (…) When I work, I forget everything. And yes, that is important to me. You don’t have to worry; you can just take care of others. The disease isn’t there for a while.”

Five studies highlighted the impact of cancer treatment side effects on the work participation of advanced cancer patients [19–21, 24, 25]. Three mentioned cancer-related fatigue [19, 20, 24], three spoke about cognitive impairment (including affected mental abilities, memory difficulties, numbness, and concentration problems) [20, 24, 25], two pointed out pain [21, 24], and two called attention to other psychological variables such as “the quest of meaning” and the “uncertainty of the illness’ course” [24, 25].

“When I came home after the very first day back at work, I was so extremely tired and overwhelmed that I couldn’t do it the next day. I was actually supposed to go in the next day, but I just couldn’t. I was exhausted for the rest of the week.”

In terms of cognitive impairment, one study highlighted that the mental abilities required to perform work were affected in patients with metastatic breast cancer [25], a second showed that memory problems and numbness were significantly associated with stopping work [20], and a third characterized concentration problems as one of the main problems interfering with work resumption [24]. In addition, pain was identified as one of the main issues hindering occupational reintegration [24] and was significantly associated with being unemployed [21].

One study showed that work ability was significantly lower in those with advanced cancer, and that a higher level of hope was positively associated with work ability [27]. This study also revealed that burnout complaints and work engagement were not significantly different between those who had advanced cancer and those who did not; it also revealed that a higher level of hope or of resilience was negatively associated with burnout complaints, and that a higher level of hope was positively associated with work engagement [27].

“It is necessary to hold on to things that belong to your life and work is part of that, even if it is only for a limited number of hours per week. It prevents you from getting lost and keeps you going. I experienced this very strongly when it turned out that I had metastasized cancer.”

3.3.3. Healthcare System

Four studies looked at the healthcare system [20, 22, 24, 25]. Regarding treatments for metastatic breast cancer, one study [22] showed that women who received more chemotherapy were less likely to be currently employed two and a half years after diagnosis, while hormonal treatment was significantly associated with continued employment in another study [20].

“I think it would have helped a lot if work had been included in my process from day one as a topic of conversation. I mean, that is such a big part of your life, for me anyway, you can’t just ignore it.”

Finally, one study [22] showed that women who exercised were much more likely to be interested in getting help from healthcare professionals regarding occupational limitations.

3.3.4. Workplace System

“There are some people who just don’t understand why I’m going to work at all or why I want to do that. (…) They don’t understand why I value work so much.”

“At one point, I really wanted to go back to my old contract, four days, and everyone just thought I was crazy for wanting that, but I thought, I’ll show them that I can come back.”

“Dare to ask questions, because of course it’s intense when an employee comes up to you like, sorry, I don’t know how long I have to live. I could be just one year. It is understandable that an employer struggles to initiate the conversation, but don’t leave it up to the patient.”

3.3.5. Legislative and Insurance Systems

“When the radiotherapy was finished, they said: “Maybe we can start an early process to apply for the IVA (full invalidity benefit regulations).” I thought that was very strange. I was only on sick leave for half a year and I thought, we are not there yet. I wondered if it was financially more beneficial for my employer.”

3.3.6. Intervention

The only interventional study examined the outcomes and feasibility of a program called “recalibraTe lifE and woRk with and afteR cAncer (TERRA)” [28]. This program consisted of five four-hour online sessions, incorporating various approaches (group discussions, paired dialogs, exercises, and homework), and was facilitated by employees from private companies. The sessions covered themes such as self-awareness and defining work objectives, work preferences and life trajectory, values and memories, strengths, aspirations, guidance, and future planning. The study demonstrated that the “TERRA” program had a modest positive impact on Readiness for Return-To-Work (RRTW), quality of life, fatigue, anxiety and depression, unmet needs, and self-efficacy. However, results relating to work ability, work intention, work–life conflict, and work involvement were inconsistent.

4. Discussion

This scoping review aimed to assess the current understanding of work resumption and retention in patients diagnosed with advanced cancer, an area that remains relatively understudied compared to early-stage cancer. The review identified 10 relevant studies, with most focusing on breast cancer patients [19, 22, 23, 25, 26] and employing quantitative methods [19–23, 26–28]. The majority of studies were carried out in the United States [19–23, 25]. Although the research on this topic is still in its early stages, certain trends are emerging that warrant discussion.

The results revealed that the ability of advanced cancer patients to RTW is influenced by a range of personal factors, including age [22, 25, 26], cancer-related symptoms [19–21, 24, 25], and psychological variables [27]. Older patients [22, 25, 26] and those from ethnic minorities in occidental countries [20, 23] were more likely to report adverse changes in employment status. This finding aligns with previous studies on early-stage cancer [29–31], suggesting that sociodemographic factors play a crucial role across cancer stages in determining work participation outcomes. Moreover, advanced cancer patients frequently report that work provides a sense of normalcy, purpose, and connection to society [24]. However, the burden of cancer-related symptoms, such as fatigue, cognitive impairments, and pain, can significantly impede their ability to maintain employment [19–21, 24, 25, 27]. Fatigue is consistently associated with reduced work productivity [19] and cessation of employment [20, 24]. Cognitive issues such as memory loss and concentration difficulties also present substantial barriers [20, 24, 25], as echoed in studies on early-stage cancer patients [29]. Notably, patients with a strong sense of hope and resilience demonstrated higher work ability [27], emphasizing the potential importance of psychological interventions to support work retention.

While treatment modalities such as chemotherapy [22] and hormonal therapy [20] directly impact employment outcomes, patients often report insufficient guidance from healthcare professionals regarding work resumption [24, 25]. The lack of focus on work-related issues in clinical settings is a recurrent theme, with patients calling for more structured support, including having a designated point of contact to whom they can address employment concerns [24, 25, 32]. This need for improved coordination between healthcare providers and occupational professionals is critical to optimizing work participation in advanced cancer patients.

Interestingly, engagement in physical activity was positively associated with interest in receiving occupational advice from healthcare providers [22], suggesting that patients who are physically active may be more proactive in seeking work-related support [33]. This finding underscores the potential benefit of integrating occupational guidance with lifestyle interventions as part of a holistic survivorship care plan.

The workplace environment plays a pivotal role in facilitating or hindering the RTW process for advanced cancer patients. Supportive employers and colleagues can significantly ease the transition back to work [24], yet many patients report experiencing discrimination, lack of understanding, or reduced job opportunities [25]. Patients often feel compelled to take the initiative in discussing their work-related needs, as employers may hesitate to broach sensitive topics such as terminal illness [24]. Encouraging open communication and fostering an inclusive workplace culture are essential to improving work outcomes for this population. Job modifications, such as reducing physical demands or working fewer hours, were identified as effective strategies for managing cancer-related fatigue [24]. However, these adjustments are not always offered or adequately supported by employers, highlighting a gap in workplace policies and practices. Furthermore, some patients expressed frustration at being prematurely encouraged to apply for disability benefits, raising concerns about potential financial motivations from employers [24].

Patients’ concerns extend beyond the workplace to encompass legal and financial issues. Many advanced cancer patients are interested in receiving information about health insurance, disability benefits, and their legal rights [25]. This demand reflects a wider issue of poor communication between occupational physicians and patients, with some feeling pressured into applying for disability benefits before they are ready [24]. Addressing these concerns through better dissemination of information and more transparent processes could enhance patients’ confidence in their employment decisions.

The TERRA program, the only interventional study identified in this review, offers a promising approach to supporting work participation in advanced cancer patients [28]. While the program showed modest improvements in RRTW, quality of life, and psychological outcomes, the impact on work ability and engagement was mixed. These results suggest that more targeted interventions may be necessary to address the specific challenges faced by this patient population, including symptom management, psychological support, and workplace accommodations.

Although many of the findings align with those from studies on cancer survivors diagnosed at an earlier stage, advanced cancer presents additional complexities. Unlike early-stage patients, whose treatments generally have a defined endpoint, advanced cancer patients typically undergo long-term or indefinite treatment. The cumulative side effects from multiple lines of therapy, combined with the cyclical nature of disease progression and remission, make it particularly challenging for these patients to maintain consistent work routines [19–21, 24, 25, 27, 28, 34]. Pain can fluctuate significantly, complicating efforts to plan and sustain employment [21, 24, 35]. The increased need for more intensive pain management, including opioids, further complicates matters, as side effects such as drowsiness can impair job performance [36].

Advanced cancer patients also face distinct social challenges. The desire to remain employed is often met with confusion or skepticism from colleagues, employers, and even family members [24], who may associate an advanced cancer diagnosis with a terminal prognosis [37]. This misunderstanding can lead to feelings of isolation and a lack of workplace support. In addition, these patients must navigate professional environments that often fail to accommodate their need for flexible working hours or task modifications, further complicating their ability to return to or retain employment [38].

4.1. Limitations and Strengths

This scoping review has several limitations. It was not feasible to consult additional databases, which limited the comprehensiveness of the research. This potential bias was addressed by systematically reviewing the references in the bibliographies of the identified articles until saturation was reached. There is also a potential selection bias, as only studies published in French and English were included.

Furthermore, in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR guidelines [17] and the framework proposed by Mak and Thomas [16], we did not conduct a formal appraisal of methodological quality, as this step is not required for scoping reviews. Our objective was to provide the broadest possible overview of the existing literature on work participation among patients with advanced cancer. However, we acknowledge that the absence of quality assessment may limit the interpretability of the findings and the strength of the conclusions, and this should be taken into account when interpreting the results.

Another important limitation of this review lies in the geographic concentration of the included studies, which predominantly originate from the United States [19–23, 25] and Western Europe [24, 26–28]. While these findings may not be directly generalizable to healthcare systems in Asia, Africa, or Latin America, is it noteworthy that research activity is beginning to emerge in Asia, particularly in countries such as South Korea [39, 40] and China [41], where recent studies have started to explore RTW outcomes among cancer survivors. This growing body of literature offers promising perspectives for future comparative and culturally informed studies.

In contrast, the landscape remains considerably less developed in many African countries. These geographic and systemic disparities underscore the need to first strengthen research and clinical frameworks within Europe, by harmonizing data collection tools and incorporating work-related outcomes in national cancer survivorship cohorts, before extending such structured approaches internationally.

Furthermore, the generalization and implementation of occupational support services depend on adequate public funding and supportive health and labor policies, which remain insufficient in many regions. Without sustainable financial investment and systemic endorsement, efforts toward cross-national adaptation may face significant barriers.

Lastly, the results should be interpreted with caution due to the predominance of studies focusing on women with advanced breast cancer [19, 22, 23, 25, 26], which limits the generalizability of the findings and to other tumor types, particularly those affecting male patients. This highlights a current limitation in the literature and underscores the need for more inclusive research.

Nonetheless, this review also has several strengths. First, it addresses a critical and timely issue, given the rising survival rates of advanced cancer patients and the increasing importance of their work participation. In addition, the use of PRISMA-ScR guidelines [17] and Loisel’s model [18] provides a structured and comprehensive framework, facilitating a systematic analysis of the included studies. Moreover, the review incorporates quantitative [19–23, 26–28], qualitative [24], and mixed-method [25] studies, offering a diverse and robust overview of the available data.

4.2. Future Directions and Clinical Implications

Given the growing population of advanced cancer patients, there is an urgent need for research and clinical interventions tailored to their specific needs [42]. Future studies should investigate strategies for optimizing work capacity, including cognitive rehabilitation [43], and pain [44] and fatigue management programs [45], as well as evaluate the effectiveness of workplace accommodations [46] such as flexible schedules and remote work options [5, 38]. Furthermore, enhancing employer and co-worker awareness through targeted training could help foster more supportive work environments for these patients [47, 48].

Despite growing recognition of work participation as an important aspect of cancer survivorship, interventional studies specifically targeting patients with advanced cancer remain limited. This may be partly due to persistent assumptions that employment is not a relevant goal for this population, given the uncertain prognosis and the chronic nature of treatment. However, existing interventions developed for patients with early-stage cancer, such as the FASTRACS program [49] or the work by Porro et al. on the RTW journey for breast cancer survivors [50], provide valuable foundations that could be adapted to address the specific needs of patients with advanced cancer. Rather than designing entirely new models, future research should prioritize the adaptation of these established interventions by integrating the unique challenges faced by this population, including fluctuating symptoms, ongoing long-term treatment, fatigue, and workplace stigma. Programs such as TERRA [28], which combine occupational counseling with coordination between oncology and occupational medicine, demonstrate the feasibility of such adaptations. Building on these approaches, we propose that future frameworks incorporate the following: multidisciplinary collaboration involving oncologists, occupational physicians, psychologists, and social workers; flexible, modular designs that accommodate evolving health conditions; telehealth options to enhance accessibility; individualized goal-setting that respects diverse employment aspirations (e.g., part-time work, volunteering, or maintaining a work identity); and early integration into care pathways, ideally beginning at diagnosis or treatment planning. To ensure the relevance and acceptability of these interventions, participatory design involving patients as co-developers should be actively encouraged.

To facilitate these adaptations, concrete tools can be used to identify patients’ employment-related concerns early in the care process. Instruments such as the RTW self-efficacy questionnaire [51] and the work ability index, even in its one-item version, which has demonstrated a strong predictive value [52], can be easily implemented during routine oncology consultations. These tools not only support timely referrals to appropriate professionals (e.g., occupational therapists, vocational counselors, and social workers) but also provide a foundation for developing hospital-based databases to monitor work-related outcomes and inform resource allocation.

In the longer term, structured intrahospital coordination pathways should be established to integrate vocational support into routine cancer care. Coordinated occupational consultations, bringing together oncologists, occupational physicians, psychologists, and social workers, could assist patients with complex needs through individualized and realistic RTW strategies. Embedding discussions about work in multidisciplinary team meetings and survivorship care plans, even for patients with advanced cancer, would further promote a holistic and patient-centered approach. To sustain these initiatives, oncology professionals should receive basic training on how to initiate conversations about work, use screening tools, and recognize when referrals are appropriate.

Importantly, future research should also aim to diversify study populations by including patients with a broader range of tumor types, particularly those underrepresented in the current literature, such as men and individuals from non-Western countries. This may involve the development of multicenter international cohorts, the integration of work outcomes into broader survivorship studies, and the implementation of targeted recruitment strategies to ensure more representative samples.

Clinically, the findings highlight the importance of personalized, multidisciplinary care that accounts for the variability in treatment responses and side effects. Healthcare providers, particularly oncologists and occupational health professionals, should collaborate closely with patients to address work-related challenges, offering guidance on legal rights, financial support, and necessary work adjustments. Incorporating these considerations into both clinical practice and public policy will be essential for improving quality of life and social participation in this vulnerable population.

5. Conclusion

This scoping review offers a comprehensive overview of the challenges surrounding work resumption and retention in patients diagnosed with advanced cancer, an area that has received limited attention compared to early-stage cancer. The review identifies the multifaceted factors influencing employment outcomes, including personal, psychological, and workplace-related barriers. Despite the early stage of research in this field, the findings underscore the importance of tailored interventions, particularly those targeting symptom management and psychological support, to enhance work participation in this population. Furthermore, the lack of sufficient guidance from healthcare professionals on employment-related issues highlights a critical gap in patient care. Addressing these challenges requires a concerted effort to develop more personalized, multidisciplinary approaches that bridge clinical care, occupational health, and policy reforms. Expanding research beyond the predominant focus on breast cancer in the United States to other cancer types and cultural settings will be essential to generating more generalizable findings. Ultimately, ensuring that advanced cancer patients receive the support necessary to maintain employment is vital for improving their quality of life and fostering greater work participation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

P.G. designed and planned the study, developed the search strategy, screened articles for eligibility, extracted and analyzed the data, interpreted the results, drafted the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript. S.J. designed and planned the study, developed the search strategy, screened articles for eligibility, and extracted the data. K.B. critically revised the scientific aspects of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript. Y.R. critically revised the scientific aspects of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript. B.P. designed and planned the study, developed the search strategy, coordinated all stages of the study, screened articles for eligibility, extracted and analyzed the data, interpreted the results, drafted the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This manuscript was prepared as part of the SIRIC ILIAD program supported by the French National Cancer Institute (INCa), the French Ministry of Health, the Institute of Health and Medical Research (Inserm), and ITMO Cancer; INCa-DGOS-Inserm-ITMOCancer_18011 contract.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.