Economic Evaluation of Traditional Treatments for Localized Prostate Cancer: A 10-Year Cohort Study

Abstract

Objectives: To perform a cost-effectiveness analysis based on primary data from a cohort of patients with localized prostate cancer followed throughout 10 years, comparing radical prostatectomy, brachytherapy, and external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) and applying disease-specific utilities, from a national health system’s perspective.

Materials and Methods: Patients diagnosed with localized prostate cancer were consecutively recruited in 2003–2005 from 10 Spanish hospitals (n = 674) (ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT01492751). The expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) and short-form 36 (SF-36) questionnaires were administered through telephone interviews before treatment and annually during follow-up. The outcome measures to evaluate the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio between treatments (ICER) were quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), calculated by the patient-oriented prostate utility scale (PORPUS) utility index, obtained with a mapping from the EPIC and the SF-36, and survival data. Ten-year medical activities were used to derive costs. Both unweighted and propensity score-weighted analyses were performed.

Results: The weighted mean of 10-year QALYs was the highest for radical prostatectomy (8.53), followed by brachytherapy (8.49) and external radiotherapy (8.20), but the difference was only statistically significant with the latter. Costs were significantly higher for brachytherapy (€21,348) than radical prostatectomy (€12,281) and EBRT (€7,560). Compared to EBRT, the weighted ICER for radical prostatectomy was €14,169/QALY gained and €48,417/QALY for brachytherapy.

Conclusion: Our findings support that radical prostatectomy was the most cost-effective alternative, but the differences in effectiveness among the three treatments were small. The incremental cost of radical prostatectomy and brachytherapy compared to EBRT, however, does not justify restricting these alternatives.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01492751

1. Introduction

Worldwide, 1.4 million new cases of prostate cancer were estimated in 2022, making it the most common noncutaneous cancer in men [1]. Prostate cancer patients present a high age-standardized 5-year relative survival, which increased in Europe from 73% to 82% in a decade [2]. Most patients are currently diagnosed in localized stages and become long-time survivors [3].

There are numerous treatment alternatives available for the management of localized prostate cancer, including surgery, radiotherapy, or active surveillance. In 2016, the ProtecT trial [4, 5] confirmed that there are no differences in overall survival among these alternatives in patients with low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Nevertheless, surgery and radiotherapy were associated with lower incidences of disease progression and metastases [4] but worse patterns of side effects through patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) [5]. On the other hand, these treatments could vary greatly in cost.

There are several European cost-effectiveness studies comparing treatments for patients with localized prostate cancer, employing different techniques to model a lifetime horizon [6–8]. Two of them, modeling data from the ProtecT trial, showed that radiotherapy is the most cost-effective alternative and it dominates open radical prostatectomy at a lifetime horizon [7, 8]. These results were also confirmed in the only nonmodeled cost-effectiveness analysis of the ProtecT trial from the UK national health system’s perspective at a 10 years’ median follow-up [9], applying societal preferences through the EQ-5D-3L, an econometric generic instrument to estimate quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). Although generic measures are widely used for economic evaluations, they do not cover the main symptoms and side effects of prostate cancer treatments (i.e. urinary, sexual, or hormonal).

As far as we know, only the cancer of prostate strategic urologic research endeavor (CaPSURE) [10] has used a prostate cancer-specific econometric instrument, the patient-oriented prostate utility scale (PORPUS) [11], for the economic evaluation of localized prostate cancer treatments. This study, applying Markov models from the US payer’s perspective over 8 years to real-world outcomes and costs prospectively collected, found that radical prostatectomy is more cost-effective than external or interstitial radiotherapy in patients with prostate cancer of low risk. The PORPUS utilities were obtained in the CaPSURE study by a mapping from the University of California-Los Angeles-prostate cancer index (UCLA-PCI), which does not cover hormonal symptoms nor storage and voiding urinary symptoms [12]. This instrument was the precursor of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC), which solved these limitations.

Our aim was to perform a cost-effectiveness analysis, with PORPUS utilities mapped from the EPIC and the SF-36, to compare external radiotherapy with radical prostatectomy and brachytherapy, from the Spanish national health system’s perspective at a 10-year follow-up. Prospective data on outcomes and cost come from the multicentric Spanish group of clinically localized prostate cancer cohort, whose results on effectiveness at 5 [13], and 10 years [14, 15] after treatment have been published.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a prospective observational study of a localized prostate cancer cohort of patients whose primary treatment had been either external radiotherapy, radical prostatectomy or brachytherapy as a monotherapy, followed from time of diagnosis to ten years post-treatment. The study was approved by the ethics review boards of the participating hospitals, and written informed consent was obtained from patients, following the 2000 revision of the Helsinki Declaration.

Study details and treatment modalities have been described elsewhere [13–15]. Briefly, newly diagnosed patients with localized prostate cancer (stages T1 or T2, and low/intermediate risk) were consecutively recruited in 2003–2005 from ten hospitals funded by the Spanish national health system. Exclusion criteria were not being treated in one of the participating centers and a previous transurethral prostate resection. The decision regarding treatment selection was made jointly by patients and physicians: 192 patients underwent open radical retropubic prostatectomy, 317 underwent brachytherapy (seeds of I125 with a prescription dose of 145 Gy to the reference isodose, 100%), and 195 patients were treated with 3-dimensional conformal external beam radiotherapy (EBRT), delivered with 1.8–2.0 Gy daily fractions.

Demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline were recorded at the clinical sites before treatment, including age, tumoral stage, PSA, and Gleason score. The EPIC-50 [12] and the short form-36 health survey (SF-36) [16] were administered centrally through telephone interviews before treatment and during follow-up at one, three, six, and 12 months after treatment in the first year and annually thereafter.

2.1. Effectiveness

Effectiveness was evaluated considering QALYs for ten years post-treatment, which is a measure of disease burden combining the value of both the length and quality of life measured with the PORPUS.

The PORPUS utility index was estimated from the participants’ responses to the EPIC-50 and the SF-36v2 through a mapping algorithm [17], which showed good predictive capacity (R2 = 0.88) and an excellent intraclass correlation coefficient (0.95). The PORPUS has a 10-attribute health state classification system that includes 5 broad items of health-related quality of life (pain, energy, social support, communication with doctor, and emotional well-being) and 5 prostate cancer-specific items (sexual function and desire, urinary frequency and incontinence, and bowel function). Response options are on 4- to 6-level Likert scales, resulting in 6,000,000 potential health states. The missing data of utilities were estimated through multiple imputations.

The PORPUS utility index, ranging from 0 (dead) to 1 (perfect health), was constructed with the multiattribute utility function estimated from 3 cohorts of patients with prostate cancer (localized, metastatic, and nonmetastatic survivors) [11], who had undergone hormonotherapy (42%), radical prostatectomy (32%), or radiotherapy (31%). QALYs were calculated by adding up the annual products of survival and utilities over the ten years of the study with a yearly discount rate of 1.5% [18].

2.2. Resource Use, Unitary Costs, and Cost Estimates

The cost analysis assumed the healthcare system’s perspective, and direct healthcare costs were estimated by micro-costing calculation and a bottom-up approach. To calculate cost, we used patient-level data from a subsample of the cohort with patients recruited at a functional unit for prostate cancer composed of two hospitals (n = 289) and a multiple imputation for the rest of the cohort. This was due to the availability of individually registered health care activities only from two centers.

Inpatient and outpatient services utilization data were collected retrospectively from the hospitals’ databases for the period between 90 days before and ten years after treatment initiation, except for the resources used during the diagnostic process before treatment, which were excluded.

Activities attributable to prostate cancer treatment were selected by a comprehensive analysis of their relationship with the disease and time sequence. Specific study data were used for including the relapse rescue treatment with hormone therapy (from the clinical follow-up form) and use of diapers for urinary incontinence (from an EPIC item). Data on hormonal therapy dispensed by pharmacies at the individual level were extracted from the regional pharmacology register.

Unit costs were obtained from reimbursement tariffs of a Spanish database of costs [19], selecting the most recent data available for each resource from the Catalan health system [20–22]. Ex-factory pharmacological prices were considered.

Adding up these costs, the direct cost of the treatment during ten years or until death was estimated for each patient. A yearly discount rate of 3.5% was applied to all costs from the year of treatment initiation [18]. Costs were in Euros, and the price was updated to April 2024, adjusted according to a median yearly inflation of 2.1%. This article has been written according to the ISPOR CHEERS checklist [23].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

To account for treatment selection bias, propensity scores were obtained from the predicted probabilities estimated in separate logistic regression models (Supporting Information, Table S1), contrasting radical prostatectomy with each of the other two treatment groups. The c-statistic obtained was 0.80 for the EBRT model and 0.92 for the brachytherapy model, indicating a good discriminant ability. The standardized morbidity ratio (SMR) weighting [24] was applied by giving a weight of one to patients in radical prostatectomy, while weights for patients in other treatment groups were defined as the ratio of the estimated propensity score to one minus the estimated propensity score. Differences among treatment groups were tested using the χ2 test for categorical variables and the ANOVA or F-Fisher test for unweighted and weighted continuous variables, respectively. All results were estimated as unweighted and weighted with propensity scores.

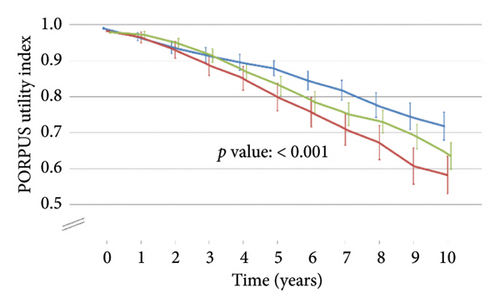

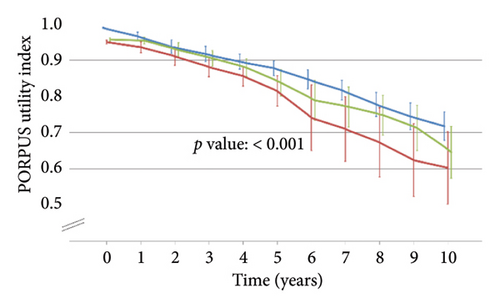

Figures were constructed showing the yearly evolution of the utility indexes and of the costs according to treatment groups. To account for repeated measures, differences among treatment groups in the time-trend evolution of these variables were tested using multilevel models for longitudinal data. We calculated the means, the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of QALYs, direct costs for each treatment group, and the difference between them, using EBRT as the reference group. To compare treatments, we estimated the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs): (mean cost of treatment X—mean cost of EBRT)/(mean QALYs of treatment X—mean QALYs of EBRT).

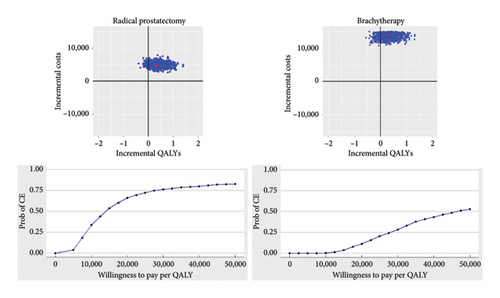

The bootstrapping method was used to assess uncertainty in the sampling distribution of the ICER. To represent graphically the uncertainty of the results, we performed a probabilistic sensitivity analysis, with all outcomes plotted in a cost-effectiveness plane showing the incremental cost and effectiveness of every random iteration. We also represented a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve to indicate the probability of cost-effectiveness according to the willingness to pay threshold, which has been established in €25,000 for the Spanish national health system [25].

Furthermore, a sensitivity analysis was performed with the generic SF-6D [16], which describes health on 6 dimensions obtained from the SF-36 (physical functioning, role limitations, social functioning, pain, mental health, and vitality), with 4-6 severity levels that describe 18,000 potential health states. The utility index was constructed applying societal preferences elicited with standard gamble [16] from a representative sample of the general public (n = 836). All analyses were performed using R version 4.2.2.

3. Results

Out of the 704 participants, 30 were excluded due to the lack of any PROM data, and the final sample included in all analyses was of 674 patients (see the flow chart in Supporting Information, Figure S1). During the follow-up, 135 participants died, 10 were lost, and finally, 476 of the remaining 529 participants completed the PROM evaluation at 10 years after treatment (median = 10.0 years; interquartile range: 8.0–10.0). The PROM completion rate of the participants while alive was 88.3%.

Table 1 shows the patients’ characteristics at diagnosis according to the primary treatment, which did not present statistically significant differences after applying propensity score weights. Figure 1 shows statistically significant differences among treatment groups in the PORPUS utility index, which decreased slightly over time from means close to 1 (perfect health) before treatment to 0.6–0.7 at the end of follow-up.

| Unweighted | Weighted applying propensity scores | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBRT | Radical prostatectomy | Brachytherapy | p value∗ | EBRT | Radical prostatectomy | Brachytherapy | p value∗∗ | |

| Participants, n | 188 | 178 | 308 | |||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 70.0 (5.3) | 64.2 (5.5) | 67.3 (6.4) | < 0.001 | 63.2 (1.0) | 64.2 (0.4) | 62.1 (1.7) | 0.369 |

| < 65 years, n (%) | 31 (16.5%) | 94 (53.1%) | 94 (30.5%) | < 0.001 | 58.5 (50.7%) | 94.0 (53.1%) | 100.6 (60.2%) | 0.301 |

| 65–70 years, n (%) | 49 (26.1%) | 59 (33.3%) | 93 (30.2%) | 40.1 (34.8%) | 59.0 (33.3%) | 34.9 (20.8%) | ||

| ≥ 70 years, n (%) | 108 (57.4%) | 24 (13.6%) | 121 (39.3%) | 16.6 (14.4%) | 24.0 (13.6%) | 31.7 (19.0%) | ||

| PSA (ng/mL), mean (SD) | 8.1 (3.4) | 7.6 (2.9) | 6.9 (2.2) | < 0.001 | 7.3 (0.5) | 7.6 (0.2) | 7.0 (0.4) | 0.336 |

| Gleason score, mean (SD) | 5.8 (1.1) | 6.3 (0.7) | 5.5 (0.9) | < 0.001 | 6.1 (0.1) | 6.3 (0.1) | 5.9 (0.2) | 0.099 |

| ≤ 5, n (%) | 97 (31.5%) | 15 (8.5%) | 48 (25.5%) | < 0.001 | 21.4 (18.6%) | 15.0 (8.5%) | 26.3 (15.7%) | 0.388 |

| 6, n (%) | 202 (65.6%) | 90 (51.1%) | 89 (47.3%) | 68.7 (59.6%) | 90.0 (51.1%) | 80.8 (48.3%) | ||

| ≥ 7, n (%) | 9 (2.9%) | 71 (40.3%) | 51 (27.1%) | 25.2 (21.8%) | 71.0 (40.3%) | 60.1 (35.9%) | ||

| Clinical T stage, n (%) | ||||||||

| T1 | 110 (58.5%) | 118 (66.3%) | 251 (81.5%) | < 0.001 | 97.8 (84.9%) | 118.0 (66.3%) | 107.6 (64.4%) | 0.074 |

| T2 | 77 (41.0%) | 60 (33.7%) | 57 (18.5%) | 17.4 (15.1%) | 60.0 (33.7%) | 59.4 (35.5%) | ||

| Tx | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | 0.2 (0.1%) | ||

| Risk group, n (%) | ||||||||

| Low | 104 (55.3%) | 84 (47.5%) | 273 (88.6%) | < 0.001 | 77.2 (67.0%) | 84.0 (47.2%) | 78.4 (46.9%) | 0.127 |

| Intermediate | 84 (44.7%) | 93 (52.5%) | 35 (11.4%) | 38.1 (33.0%) | 94.0 (52.8%) | 88.8 (53.1%) | ||

| Neoadjuvant hormonal treatment, n (%) | ||||||||

| No | 129 (68.6%) | 162 (91.0%) | 205 (66.6%) | < 0.001 | 97.8 (84.9%) | 162.0 (91.0%) | 149.5 (89.4%) | 0.530 |

| Yes | 59 (31.4%) | 16 (9.0%) | 103 (33.4%) | 17.4 (15.1%) | 16.0 (9.0%) | 17.7 (10.6%) | ||

- Note: EBRT: external beam radiotherapy.

- Abbreviations: PSA, prostate-specific antigen; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error.

- ∗p value was obtained with the χ2 test or the ANOVA.

- ∗∗p value was obtained with the χ2 test or the F-Fisher test.

The costs for the 289 patients with recorded information on their use of resources and overall treatment costs for the total sample after imputation are shown in Table 2. The total cost of primary treatment was €3,977.81 for EBRT, €4,640.01 for radical prostatectomy, and €18,601.37 for brachytherapy. Patients who underwent EBRT needed more medication (€2,343.00); radical prostatectomy patients presented a higher total cost for other related treatments (€1,683.85), tests (€2039.28), and other resources (€2,189.87); and those in brachytherapy needed more outpatient and emergency visits (€2,353.69). After applying imputation in cost variables, the discount rate of 3.5%, and propensity score weights, the overall costs were €7,560 for EBRT, €12,281 for radical prostatectomy, and €21,348 for brachytherapy. The evolution of costs over time is shown in Supporting Information, Figure S2.

| EBRT | Radical prostatectomy | Brachytherapy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean units (SD) | Mean cost (SD) | Mean units (SD) | Mean cost (SD) | Mean units (SD) | Mean cost (SD) | |

| Primary treatment | 1.0 | 3977.81 | 1.0 | 4599.01 | 1.0 | 18,601.37 |

| Number of EBRT sessions | — | — | 0.5 (3.9) | 40.99 (347.84) | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Hospitalization | ||||||

| Number | 0.0 | — | 1.0 | — | 1.0 (0.1) | — |

| Days | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.8 (3.0) | a | 3.1 (0.6) | a |

| Total primary treatment cost | 3977.81 (0.00) | 4640.01 (347.84) | 18,601.37 (0.00) | |||

| Other related treatments | ||||||

| EBRT | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.4 (10.0) | 304.35 (902.15) | 0.6 (4.7) | 55.90 (425.74) |

| Other hospitalizations | ||||||

| Number | 0.1 (0.5) | — | 0.2 (0.7) | — | 0.1 (0.4) | — |

| Days | 0.6 (5.5) | 614.11 (5543.85) | 1.3 (6.1) | 942.37 (4240.14) | 0.5 (2.0) | 324.72 (1377.96) |

| Other surgery | 0.0 (0.1) | 3.19 (29.55) | 0.2 (0.9) | 437.12 (2655.00) | 0.1 (0.6) | 306.17 (1358.79) |

| Total other treatment cost | 617.30 (5543.57) | 1683.85 (6559.82) | 686.79 (2683.54) | |||

| Visits | ||||||

| Outpatient visits | 15.3 (8.5) | 1161.74 (631.96) | 21.5 (21.4) | 1638.05 (1456.93) | 24.8 (9.7) | 1847.91 (751.59) |

| Emergency visits | ||||||

| Number | 0.2 (0.7) | — | 0.4 (1.1) | — | 0.5 (1.8) | — |

| Days | 0.2 (1.0) | 146.74 (783.33) | 0.5 (1.4) | 448.10 (1165.16) | 0.6 (1.9) | 501.68 (1679.57) |

| Day hospital | 0.1 (0.4) | 13.81 (91.85) | 0.3 (1.1) | 62.25 (272.89) | 0.0 (0.1) | 4.10 (31.19) |

| Total visits cost | 1343.07 (1231.43) | 2148.40 (2048.54) | 2353.69 (2058.58) | |||

| Test | ||||||

| Laboratory | 13.2 (12.3) | 788.79 (733.02) | 23.8 (8.4) | 1420.41 (501.04) | 17.9 (8.8) | 1068.60 (525.12) |

| Emergency laboratory | 0.5 (1.9) | 29.19 (110.68) | 3.2 (3.2) | 188.37 (191.00) | 1.8 (2.2) | 108.20 (133.62) |

| Biopsy | 0.0 (0.2) | 4.22 (27.51) | 1.1 (0.4) | 204.00 (73.72) | 0.2 (0.6) | 28.16 (100.85) |

| X-rays | 0.9 (2.8) | 14.78 (45.81) | 2.3 (2.7) | 37.43 (43.39) | 0.9 (1.5) | 14.90 (23.90) |

| Echography | 0.2 (0.6) | 7.12 (17.20) | 0.4 (1.0) | 12.41 (29.74) | 0.6 (1.3) | 19.40 (39.90) |

| CT-scan | 0.2 (0.5) | 22.24 (62.21) | 0.4 (0.9) | 44.52 (106.31) | 0.1 (0.4) | 12.37 (43.01) |

| Gammagraphy | 0.5 (1.0) | 47.01 (102.48) | 0.3 (1.0) | 30.67 (97.00) | 0.6 (1.5) | 59.24 (150.30) |

| Electrocardiogram | 0.0 (0.1) | 0.27 (2.46) | 0.7 (0.6) | 14.95 (13.00) | 0.2 (0.6) | 5.51 (13.73) |

| Other tests | 0.1 (0.3) | 22.58 (134.39) | 0.5 (1.3) | 86.52 (226.39) | 0.2 (0.8) | 39.16 (148.62) |

| Total tests cost | 936.21 (915.94) | 2039.28 (738.65) | 1355.53 (774.41) | |||

| Medication (hormonotherapy) | 12.5 (18.9) | 2343.00 (3896.80) | 3.3 (11.3) | 621.10 (2178.04) | 2.4 (9.6) | 199.92 (808.89) |

| Total medication cost | 2343.00 (3896.80) | 621.10 (2178.04) | 199.92 (808.89) | |||

| Other resources | ||||||

| Diapers | 185.7 (754.1) | 193.43 (785.51) | 1820.1 (2490.9) | 1896.03 (2594.84) | 301.7 (1051.9) | 314.27 (1095.81) |

| Cures | 0.0 (0.1) | 1.55 (14.42) | 1.1 (0.9) | 143.83 (122.12) | 0.1 (0.4) | 9.22 (55.22) |

| Penile prosthesis | 0.0 (0.1) | 77.33 (717.09) | 0.0 (0.1) | 91.72 (778.29) | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Bone metastases treatment | 0.0 (0.1) | 21.88 (202.95) | 0.0 (0.1) | 12.98 (156.30) | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Nursing visits | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 (1.2) | 20.72 (44.82) | 0.1 (0.8) | 5.25 (30.60) |

| Telephone consultation | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 (0.1) | 0.36 (4.33) | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Parameter control and monitoring | 0.0 (0.1) | 0.30 (2.76) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Rehab session | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 (1.2) | 22.81 (274.72) | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Inpatient interconsultations | 0.0 (0.1) | 2.39 (22.14) | 0.0 (0.1) | 1.42 (17.05) | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Total other resources cost | 296.88 (1062.64) | 2189.87 (2773.60) | 328.74 (1111.41) | |||

| Overall treatment costs | ||||||

| Without imputation nor discount rate (DR), n = 289 (SD) | 9514.26 (8556.90) | 13,322 (9273.55) | 23,526.04 (5114.56) | |||

| With imputation and discount rate (DR), n = 674 (SD) | 9151 (456) | 12,281 (469) | 22,148 (357) | |||

| With imputation, DR, and PS weights, n = 674 (SE) | 7560 (518) | 12,281 (624) | 21,348 (413) | |||

- Note: EBRT, external radiotherapy. Bold values are the rows with information on total costs of each section.

- Abbreviations: DR, discount rate; PS, propensity scores; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error.

- aIncluded in cost of primary treatment.

Table 3 shows QALYs, costs, and ICERs over the 10-year period. After applying propensity score weights, QALYs were higher for radical prostatectomy (8.37) than for brachytherapy (8.21) and EBRT (7.98), but the difference was only statistically significant with the latter. EBRT was also statistically significantly cheaper than radical prostatectomy and brachytherapy. Compared to EBRT, the ICER was €14,169 per QALY gained for radical prostatectomy and €48,417 per QALY gained for brachytherapy, after applying propensity score weights. The results of the sensitivity analysis performed with the generic SF-6D are consistent with the main results obtained with PORPUS, although with lower QALYs (Supporting Information, Table S2).

| EBRT | Radical prostatectomy (RP) | Brachytherapy (BT) | Difference EBRT-RP | Difference EBRT-BT | Difference BT-RP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-year QALYs | ||||||

| Unweighted | 7.88 (0.13) [7.63; 8.13] | 8.53 (0.13) [8.28; 8.79] | 8.17 (0.10) [7.97; 8.36] | −0.65 (0.18) [−1.09; −0.22] | −0.29 (0.16) [−0.68; −0.10] | −0.37 (0.16) [−0.76; 0.03] |

| Weighted with the propensity score | 8.20 (0.10) [8.01; 8.39] | 8.53 (0.09) [8.35; 8.72] | 8.49 (0.12) [8.25; 8.72] | −0.33 (0.14) [−0.66; −0.01] | −0.28 (0.15) [−0.65; 0.08] | −0.05 (0.15) [−0.41; 0.32] |

| 10-year costs | ||||||

| Unweighted | 9151 (456) [8255; 10,048] | 12,281 (469) [11,360; 13,202] | 22,148 (357) [21,448; 22,849] | −3130 (654) [−4701; −1559] | −12,997 (579) [−14,387; −11,607] | 9867 (589) [8453; 11,281] |

| Weighted with the propensity score | 7560 (414) [6747; 8374] | 12,281 (402) [11,493; 13,070] | 21,348 (499) [20,369; 22,328] | −4721 (671) [−6106; −3336] | −13,788 (671) [−15,345; −12,232] | 9067 (640) [7530; 10,604] |

| ICERs (€/QALY) | ||||||

| Unweighted | 4815 | 44,817 | a | |||

| Weighted with the propensity score | 14,169 | 48,417 | a |

- Abbreviations: ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; QALYs, quality-adjusted life years.

- aLower QALYs and higher costs do not permit to estimate an ICER in these treatment groups.

Figure 2 shows the cost-effectiveness plane and acceptability curves. Both radical prostatectomy and brachytherapy would usually be costlier and more effective than EBRT, though radical prostatectomy is a more efficient option, with a probability of being cost-effective of almost 75% for a willingness to pay of €25,000 per QALY gained. On the other hand, the benefit in QALYs in brachytherapy is uncertain, while it significantly increases cost in the probabilistic sensitivity analysis. In fact, the acceptability curve shows that brachytherapy is not likely to be cost-effective compared to EBRT at any low willingness to pay. The sensitivity analysis with the generic SF-6D is also consistent with the PORPUS, although the willingness-to-pay is lower in both radical prostatectomy and brachytherapy (Supporting Information, Figure S3).

4. Discussion

Our study provides long-term results of cost-effectiveness for three of the most established attempted curative treatments in localized prostate cancer patients, obtained with observational data and applying propensity score weights. Over a 10-year period, only small differences were observed in QALYs among treatment groups, but patients treated with radical prostatectomy or brachytherapy incurred greater costs than those who underwent EBRT. However, the costs differences between treatments (from €4721 to €13,788) are not enough to consider any of the alternatives as not sustainable from the national health system’s perspective in patients with low and intermediate risk.

Our results on effectiveness, showing small differences in QALYs among the three treatment groups, which were only significant between EBRT and radical prostatectomy, are consistent with those obtained in the ProtecT trial [9] and the CaPSURE registry [10]. Nonetheless, the QALYs estimated in our study for external radiotherapy and radical prostatectomy (8.2 and 8.5) were higher than those observed in the ProtecT (6.9 and 7.1), also with a 10-year time horizon, but estimated with the EQ-5D-3L [9]. The QALYs obtained with the SF-6D in our study (6.8–7.2) are closer to those in the ProtecT trial, probably because both instruments are generic (see sensitivity analyses in Supporting Information, Figure S4). These lower utilities obtained with SF-6D or EQ-5D-3L would probably reflect the general health deterioration due to the aging process and associated multimorbidity, which is better covered by a generic instrument than by a disease-specific one.

Furthermore, the QALYs obtained with PORPUS for patients with low-risk prostate cancer in CaPSURE (7.7, 6.2, and 6.9 for radical prostatectomy, EBRT, and brachytherapy, respectively) were also lower than ours, which were all above 8. Differences could be partly explained by the lack of hormonal symptom assessment and the underestimation of urinary symptoms derived from data collected through the UCLA-PCI. Furthermore, the mapping algorithm applied in our study includes the prostate cancer-specific EPIC and the generic SF-36 instruments, covering both types of PORPUS’ constructs and achieving a higher predictive capacity (R2 = 0.88) [26], compared with the mapping applied in the CaPSURE study (R2 = 0.72) [27].

Our costs are higher than those published from the ProtecT trial [9], converted into euros and updated for inflation up to April 2024 ― €12,281 vs €7,942 (£7,519) for radical prostatectomy; and very similar €7,560 vs €7,776 (£7,361) for EBRT ―, but much lower than treatment costs from the CaPSURE study [10]. The latter also differs from our results in the relative cost differences between treatment options, being EBRT the most expensive treatment in CaPSURE (€51,208.57; $60,718), followed by radical prostatectomy (€46,435.86; $55,059) and brachytherapy (€33,506.79; $39,729). It is important to highlight this difference in radiotherapy costs among studies: external radiotherapy is the cheapest in the Spanish and British studies [9], but the most expensive one in the CaPSURE [10]. This could be partly explained by the differences among European and US health systems, which hinder the generalization of results in costs. Moreover, it is important to consider that there are also differences in the proportion of the treatment costs that are covered by the health system or paid by each patient. In our study, the Spanish health care system covered almost all costs, except for a very small out-of-pocket amount, mainly for medicines taken at home.

Due to the tight differences in QALY benefits among the three treatments, no alternative is dominant. Both results in the ICER and the acceptability curve consistently indicate that radical prostatectomy is a cost-effective alternative in comparison to EBRT, with a probability of being cost-effective of almost 75% for a willingness to pay €25,000 per QALY gained. Otherwise, brachytherapy is the most expensive and not a cost-effective alternative from the willingness-to-pay threshold of €25,000 per QALY gained. In the same line, the CaPSURE registry [10] estimated that radical prostatectomy would be cost-effective compared to brachytherapy with an ICER of $18,926 (€15.912) per QALY gained, and it would dominate EBRT in patients with low-risk prostate cancer. Furthermore, none of these ICERs for radical prostatectomy reach the willingness-to-pay thresholds in the Spanish national health system (€25,000 per QALY gained) [25], nor in the US system ($50,000 per QALY gained) [28].

Additionally, the multicentric Spanish group of clinically localized prostate cancer cohort did not include patients undergoing active surveillance, so this option could not be assessed in our economic evaluation. Results of the nonmodeled cost-utility analysis of the ProtecT trial concluded that active monitoring was the dominant alternative at 10 years for younger and lower risk patients [9]. However, it tends to be dominated over a lifetime horizon due to the risk of disease progression and metastasis in the modeled analyses [7, 8]. Other economic evaluations have also found that active surveillance is more cost-effective than radical prostatectomy [29], brachytherapy, and intensity-modulated radiotherapy [30]. Furthermore, the available evidence on efficacy and effectiveness endorses active surveillance to be currently considered the best management option for patients with very low- or low-risk prostate cancer in American and European urological guidelines [31, 32].

Nevertheless, some limitations of this study should be considered. First, the main concern regarding observational studies is treatment selection bias because participants were not randomly assigned to treatment arms. However, the propensity score weights achieved the balance in the distribution of baseline clinical characteristics among treatment groups. Second, active surveillance was not included in our economic evaluation; therefore, our findings do not encompass the full spectrum of the most established management strategies for localized prostate cancer. Third, since treatment was applied during 2003–2005, the procedures used (3D-conformal radiation, open radical prostatectomy, and preplanned brachytherapy) differed from modern techniques such as the robotic surgery, real-time brachytherapy, or intensity-modulated external radiotherapy. However, economic evaluations based on modeled data [33, 34] showed negligible increments both in costs and QALYs for these new modalities. Finally, our economic evaluation was performed from the perspective of the Spanish health system. Nonetheless, performing the study from the society’s perspective required information on indirect costs, which is not recorded in administrative databases and/or medical records.

5. Conclusions

Findings from our primary economic evaluation at a median of 10 years after treatment of low- and intermediate-risk localized prostate cancer showed that no treatment is dominant, but radical prostatectomy seems the most cost-effective alternative. However, the differences in effectiveness among the three treatments were small. Similarly, although EBRT is cheaper than surgery and brachytherapy, the magnitude of their incremental cost does not justify restricting them. Our results support that health providers should continue offering all three treatments, considering the whole range of outcomes (side effects, progression, and mortality) when the clinical practice guidelines would recommend specifically one therapeutic modality or another. It is important to consider each patient’s preferences regarding their treatment strategy, with personalized information about the potential risks and benefits, during the shared decision-making process.

Disclosure

The funders of the study had no role in the study concept and design, acquisition of data, support, analysis, or interpretation; they also had no role in the preparation, writing, reviewing, and submission of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Study concept and design: V.Z., V.B., M.Á., and M.F. Acquisition of data: C.G., J.F.S., A.G., V.M., A.M., A.H., I.H., P.C., J.P.D.L., G.S., F.G., and M.C. Statistical analysis: A.P. Data interpretation: A.P., V.Z., G.B., V.B., F.C., and M.F. Drafting of the manuscript: V.Z. and G.B. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: V.B., O.G., M.Á., C.G., J.F.S., A.G., V.M., A.M., A.H., I.H., P.C., J.P.D.L., G.S., M.R.-V., F.C., and M.F. Obtained funding: M.F. and O.G. Study supervision: O.G. and M.F.

V.Z. and G.B. contributed equally to this work.

Funding

The study was funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and cofunded by the European Union (grant numbers: PI02/0668, PI08/90090, PI13/00412, and PI21/00023), Proyectos Estratégicos of the Fundación Científica Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer (PRYES223070FERR), Generalitat de Catalunya (grant numbers: AGAUR 2021 SGR 00624 and Exp. 2021 XARDI 00005), and CIBER de Epidemiología y Salud Pública CIBERESP (research funding CB06/02/0046).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Gemma Vilagut for her advice and statistical consulting for the imputations. They would also like to thank Áurea Martin for her proofreading, manuscript editing, and submission preparation process.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Table S1: Logistic regression models for external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) and brachytherapy to obtain propensity scores, comparing with radical prostatectomy: coefficient and standard error (SE).

Supporting Information Figure S1: STROBE flowchart of the participants.

Supporting Information Figure S2: Direct healthcare costs unweighted (A) and weighted with propensity scores (B) by year and by the treatment group (n = 674): EBRT (red line), radical prostatectomy (blue line), and brachytherapy (green line).

Supporting Information Table S2: Ten-year quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) obtained with short form (SF)-6D, costs, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs): unweighted and weighted means (SE) (95% confidence interval) (n = 674).

Supporting Information Figure S3: Cost-effective plane and acceptability curves for radical prostatectomy and brachytherapy (vs. EBRT), weighted with propensity scores, and QALYs (SF-6D) estimated using bootstrapping from the National Health System.

Supporting Information Figure S4: Mean scores of the SF-6D utility index unweighted (A) and weighted with propensity scores (B), at baseline and annual follow-ups per treatment group: EBRT (red line), radical prostatectomy (blue line), and brachytherapy (green line).

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.