Improving Sexual Well-Being Support for Men With Prostate Cancer: The Health Professional Perspective

Abstract

Purpose: The provision of evidenced-based sexual well-being support is considered a key metric of quality prostate cancer care. However, patients continually report high rates of unmet sexual health needs. To provide insight into the challenges healthcare professionals (HCPs) face in delivering sexual well-being support, we conducted a qualitative study.

Methods: HCPs were recruited via professional organisations/networks and snowballing. Interviews were semistructured, conducted via telephone/video and transcribed verbatim. Interviews explored work experience, sexual support provided, challenges faced and areas of prioritisation to improve care delivery. Data were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis. The lack of representation from urologists and radiation oncologists was a limitation.

Results: Twenty-one HCPs were interviewed, including nurses, pharmacists, sexologists, a physiotherapist and an oncologist. Eight key themes were identified. Themes 1–5 describe the challenges faced by HCPs in providing sexual well-being support, such as logistical issues and reliance on other HCPs. The remaining three themes describe areas of change recommended by HCPs to improve delivery of support, including standardisation of penile rehabilitation guidelines, training for specialists and GPs and prioritisation of multidisciplinary sexual well-being support as part of routine care.

Conclusions: HCPs face several challenges in providing sexual well-being support to prostate cancer patients, which could be ameliorated through greater awareness and education about the importance of sexual well-being support and through standardising pathways and guidelines. Addressing challenges faced by HCPs in the delivery of sexual well-being support may ultimately improve patient experiences and reduce unmet sexual health needs following prostate cancer treatment.

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in Australian men, affecting one in five men in their lifetime [1]. Although prostate cancer is a highly treatable disease and the 5-year survival rate exceeds 95% [1], patients will experience a plethora of short- and long-term side effects from treatment, particularly regarding their urinary, bowel and sexual function [2]. Quality survivorship care should involve the regular assessment and management of common treatment-related side effects, such as psychological distress, urinary, sexual and bowel dysfunctions and cancer recurrence monitoring. Ideally, it is recommended that prostate cancer survivorship care be managed by a multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals (HCPs), encompassing the urologist, other specialists including radiation and/or medical oncologists, prostate cancer specialist nurses, general practitioners (GPs) and allied health professionals [3].

Sexual well-being concerns are one of the most frequently reported unmet needs identified by prostate cancer survivors across all treatment modalities [4, 5], and research has demonstrated that sexual dysfunction significantly impacts men’s quality of life, self-esteem, mental health, relationships and masculinity [2, 6]. An international panel recently published their recommended guidelines on sexual healthcare for prostate cancer patients [7]. They considered the provision of evidence-based clinical care on sexual well-being to be a key metric of quality prostate cancer care. They strongly recommended that clinicians initiate discussions about sexual well-being prior to treatment, provide information on the likely outcomes of treatments on sexual function, discuss treatment for erectile dysfunction, counsel patients on lifestyle modifications and offer to provide/facilitate psychosexual support for patients not coping well [7].

Despite these expectations, research routinely identifies shortfalls in the care provided as a common cause for patient’s unmet sexuality needs posttreatment, such as the lack of clinician-initiated discussion or sense of responsibility for managing sexual well-being [8–12], and a perceived lack of education and comfort discussing and managing sexual issues (particularly for nonheterosexual patients) [13–16]. Given patients continue to report unmet sexual needs [17, 18] and do so up to 15 years postdiagnosis [5], barriers to the delivery of sexual well-being support should be further explored. Previous research in general healthcare settings suggests HCPs may avoid discussing sexual issues with patients due to a lack of knowledge/skills, poor confidence and concerns of offending patients [19]. It is highly likely that HCPs face additional challenges in providing support, particularly in the prostate cancer setting, as they are expected to provide information and support to patients in relation to sexual health issues within very short appointment times. By exploring and identifying the challenges in healthcare delivery from the HCP perspective, recommendations for change can be made to improve patient outcomes and experiences. Therefore, we conducted a qualitative study with HCPs involved in the provision of sexual well-being information and support to men with prostate cancer, with the aim of providing an in-depth insight into the challenges faced by HCPs in providing sexual well-being survivorship care.

2. Methods

This study was part of a broader research project investigating sexual well-being and support for prostate cancer patients and received ethics approval by the Southern Adelaide Clinical Human Research Ethics Committee in November 2023 (LNR/23/SAC/146).

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

Eligible participants included any HCP working in Australia with experience caring for, or providing information and/or support, to prostate cancer patients, who were aged 18 years or older and proficient in English. Study advertisements were distributed via professional networks and organisations (such as the Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia), and those who registered their interest in the study were provided an information sheet and consent form to complete prior to the scheduling of an interview. Snowball recruitment methods were also utilised to recruit HCPs from those already participating in the study. We aimed to recruit a variety of HCPs, including clinical specialists, nurses, pharmacists and allied health professionals. As per Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis approach [20], the intention of recruitment was to include a broad range of HCPs involved in prostate cancer patient care and conduct rigorous interviews to ensure deep, meaningful data were collected.

2.2. Data Collection

All participants were recruited and interviewed by a female researcher (M.C.) with qualifications (PhD) in psycho-oncology and prostate cancer, and previous experience interviewing and conducting qualitative research methods. Participants were individually interviewed in March–April 2024, via telephone/video, and all interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. On the commencement of the interviews, the interviewer introduced themselves and detailed their role in the study, previous research experience and the study background/aims. Formal field notes were not taken, and transcripts were not returned to participants for review. Interviews were on average 62 min in length (ranging 44–87 min). A semistructured interview guide was used (see supporting information), which incorporated open-ended questions and prompts created by the authors. The guide was based on a review of previous research, clinical experience and through consultation with a prostate cancer patient advisory group. The interviews explored the HCPs work experience/background, the sexual well-being support they typically provide to prostate cancer patients and challenges in providing support.

2.3. Data Analysis

Transcripts were analysed using Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis approach due to its flexibility and adaptability as the analyses were exploratory [21]. This included six key stages: (1) immersion and checking of the transcribed interviews to ensure accuracy and familiarisation to the content; (2) initial coding of transcripts which involved both inductive coding and deductive coding of all raw data based on a simple framework adapted from the interview guide; (3) categorisation of codes; (4) refinement of categories into meaningful themes; (5) formalisation of defined themes; and (6) summarisation of themes with extracts from the data [21]. Some codes and themes were discarded during the analysis process as they either were not related to the research aims or were not backed up by enough data to draw meaningful conclusions. Analysis was primarily conducted by author M.C., though regular discussion of emerging codes and themes during the interview and early analysis process occurred with author K.B. The proposed themes, supported with extracts, were discussed with author K.B. prior to the final analysis. A summary of the results was provided to participants for comment prior to study publication. Illustrative quotes presented are notated with the participant’s number and occupation.

3. Results

3.1. Sample

Twenty-one HCPs were interviewed (out of 26 whom expressed interest). Those who were not interviewed were either unable to participate due to scheduling conflicts, nonresponse to interview scheduling follow-up or site-specific issues relating to the participation in research. The 21 participants comprised 13 nurses (including prostate cancer specialist nurses, urology nurse consultants and nurse practitioners), four pharmacists specialising in men’s health, two sexologists, one men’s health physiotherapist and one medical oncologist. Just over half of the participants (13/21) were women. A detailed overview of participant characteristics (gender, profession and speciality) is available in the supporting information. Participants worked in settings across Australia (varying in geographic remoteness) and in both private and public healthcare settings.

3.2. Overview of Themes

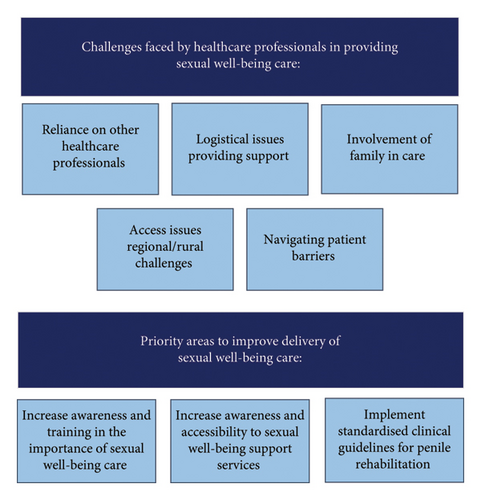

Based on our research aims and the perspectives of HCPs in the interviews, we identified eight key themes (Figure 1). The first five themes relate to the challenges faced by HCPs in providing sexual well-being support to prostate cancer patients (and their partners/families). Challenges included (1) reliance on other HCPs, (2) logistical issues in providing support, (3) the involvement of family in patient care, (4) specific regional/rural challenges and (5) navigating and overcoming patient barriers. The remaining three themes describe the areas of change identified by HCPs that were recommended to improve the provision of high-quality support to prostate cancer patients. These included wanting (6) increased awareness for the importance of sexual well-being in survivorship care, (7) increased awareness, accessibility (and provision) of support services and (8) standardised guidelines for penile rehabilitation after prostate cancer diagnosis. These themes are discussed in turn below, with accompanying illustrative quotes.

3.3. Challenges Faced by HCPs in Providing Support

HCPs involved in the study viewed sexual well-being as an essential part of survivorship care and, in general, described themselves as having sufficient knowledge and understanding of the issues patients face regarding the impact of prostate cancer treatment on sexual well-being. However, they described experiencing several challenges and issues related to the provision of sexual well-being support, which are discussed in turn below.

3.3.1. Reliance on Other HCPs

Urologists will be like, I don’t know how to write up for that drug, get your GP to do it. And the GP goes oh, I don’t write these scripts, the urologist needs to deal with it. And then there’s the patient going well, who’s doing this? So that′s yeah, quite tricky. (Participant #2, Pharmacist)

It′s been hard, you know, getting people to trust you. You know. Other people like the urologists were fine but getting the radiation oncologists and the medical oncologist to trust me to do this sort of stuff, because they didn′t know me [was hard]. (Participant #7, Nurse).

Our service doesn′t allow us to do that education. It′s quite time consuming. We just don′t have the resources. So we refer a lot of our patients. (Participant #4, Nurse).

It′s hard to convince men to pay to go and see a sexologist, or someone who will talk about intimacy, I don’t do those conversations very well… I don′t think I′m well equipped with the skill set to really to counsel them appropriately around, you know, maybe different intimacy strategies or things to try. I mean, I′m just, I′m not a psychologist, and I don′t have that skill set as part of what I do. So that′s a challenge and definitely a gap in the service … I′d love to be able to do a referral service where we could get them seen by, you know, a psychologist who has a special interest in sexual health or a sexologist and manage them that way, because I think a lot of relationships would benefit from that. (Participant #3, Nurse).

3.3.2. Logistical Challenges in Providing Support

I normally refer them to a website… mainly because of time constraints and also we don′t have much physical space in our clinic, and nowhere we can have an intimate conversation for sure. You′ll get walked in on. (Participant #4, Nurse).

If you phone them, you don′t know where they are. And I usually have to seek permission like, like one gentleman was in a golf course. So we′re not gonna talk about sexual function today… That to me is a challenge. (Participant #15).

I ended up just buying [the injection medicine] myself, because I′m like this is what I need in my clinic to give the best care. So not ideal… And the same with the vacuum pumps…There′s just no budget, I guess, for miscellaneous needs. But you know, I just went and bought them as well. So I have some pumps to show patient. (Participant #16, Nurse).

3.3.3. Involvement of Family in Care

“my hardest one is the old man that turns up with his daughter. You can’t ask [about sexual function]” (Participant #15, Nurse).

I find the difficult ones are when the partner′s not that supportive. I actually had to ask a partner to leave the clinic for the first time in 9 years. Because she was just so derogatory, so negative. Just did not understand that this was not about him getting his erections back for intimacy. It was he just didn′t feel like a man anymore. And he was very depressed. (Participant #18, Nurse).

3.3.4. Regional/Rural Challenges

Because some GPs don’t want to do it, won’t write them. They don’t know enough about it. So I used to have to get them to the urologist to write the script, but I can’t now. It’s very limited here. (Participant #5, Nurse)

So one of our barriers would be remote, rural and remote, and no phone or internet. So we′ve got a whole massive part of our catchment area for men that we look after… [that] has no phone or internet unless they have landline at home. (Participant #1, Nurse)

3.3.5. Navigating and Overcoming Patient Barriers

The financial restraints are difficult. So I′ll talk to people about trying different things. And they′ll, they′ll say to me, I can′t afford it. Yeah, I′ll say, Oh, what about we try this, I can′t afford it. And so there′s this really pushed back that they want me to fix the problem, but they′re not sort of able to commit to, to what that might require. (Participant #3, Nurse).

Cost comes up quite a bit, especially with vacuum pumps, too, and certainly the prosthesis surgeries. Well, yeah, you know, if you′ve got private health, we do them publicly here at the hospital, but they′re on a waiting list, and they could wait 5 to 10 years to get it done. (Participant #7, Nurse).

Unfortunately, there′s no Medicare rebate for a patient to see us [pharmacists]… But a public patient I waive that fee personally, so I′ve essentially seen them for free out of my own time. One to try and strengthen the relationships of referral. And two, because I really want these guys to spend their money on getting a product that they need. So if it′s a difference between paying to see me or paying to get a product, I’d prefer for them to walk out with something that they can use to actually better themselves. (Participant #2, Pharmacist).

Often with the guys that have had surgery, their focus is predominantly on their incontinence. And so they will say to me, I just want to get this incontinence sorted first, and then I′ll worry about my sexual function. And I say to those guys, if that′s a priority for you down the track… we need to do them simultaneously, we need to manage both now. Because the longer you delay penile rehab, the more difficult it is to basically rehabilitate that organ. And we talk about vascular blood flow and the fact that if that′s not happening, you will get shrinkage in the penis, you′ll get this decompression of the veins, and it will make it harder to work on erections after. So that group are challenging to convince to start penile rehab. (Participant #3, Nurse).

And so many patients will come in and they′ll really downplay how much it bothers them like, you know, one guy last week was saying to me, you know it′s not the end of the world. There are so many other people who are more unlucky than me. But I want, I want this. And you know, explaining to the patients that you know prostate cancer treatments are awful, and the importance of survivorship care, and the importance of quality of life. You know, when they finally get it, and that they see that you take this seriously. They′re like, Oh, okay, cool. Like. I don′t need to be embarrassed about wanting this to be fixed. (Participant #6, Nurse).

3.4. Areas of Change Needed to Improve Provision of Support to Patients

HCPs identified several priority areas that they felt required improvement or change, for them to better provide patients with comprehensive, high-quality sexual well-being support. These areas generally centred around the notion that sexual well-being and penile rehabilitation must be given more attention and considered more seriously by the healthcare system at large, beginning with the HCPs and extending to peak bodies such as government, professional organisations and non-for-profits. The following themes summarise the ways in which awareness could be raised and the changes to the existing system that could improve care provision, and ultimately, patient outcomes.

3.4.1. Increase Awareness of the Importance of Sexual Well-Being in Survivorship Care

[We need] a better culture around this service, the sexual health more broadly, and erectile function, penile rehabilitation. That conversation needs to be coming from every avenue and needs to have multiple checkpoints in the health system. (Participant #2, Pharmacist).

I′d love our doctors to actually realize the importance of sexual health for people… I really think our doctors need education. I think our GP’s need education. GP’s dismiss and just go here′s a script for Viagra good luck, catch you later. I know they′re busy. But like, we′re all busy, right? (Participant #1, Nurse).

A couple of our consultants tend to say we don′t need to address anything with sexual health or sexual wellbeing till 12 to 18 months… I actually have asked why do you not address penile rehabilitation and the psychosocial impacts of sexual wellbeing earlier? They don′t have an answer, other than ‘we’re about curing the cancer’. I′m like, yeah, that′s nice. But now these people actually have to live a whole life. Their marriage may break down, their family relationships, their friendship circle. (Participant #1, Nurse).

“[The nurse] absolutely drummed it into me that’s it’s bloody important. And it is incredibly important. So I actually raise it now.” (Participant #17, Medical Oncologist).

3.4.2. Increased Awareness, Accessibility and Existence of Support Services

The other part is just not having any real official training. Where we can go and say, Yep, I′m now accredited as a men′s health pharmacist. That doesn′t exist. So if it did, it might make those initial conversations a bit easier. (Participant #9, Pharmacist).

That′d be one thing, getting to see physio preoperatively, and perhaps in the public space, making specialized physiotherapy accessible to public patients. (Participant #21, Physiotherapist).

We have one sexologist here in [Town]. But her books are closed. They′ve been close for 3 years. So I do not refer anyone there. But we have a public sexual health clinic that we can refer to. I don′t refer there too often. Probably because there′s quite a long wait list. (Participant #1, Nurse).

HCPs in this study indicated that the ability to routinely involve such services in patient survivorship care would improve patient outcomes and allow them to provide more robust, comprehensive support to patients, in addition to reducing their already high workload. Participants called for additional funding and awareness for such services/experts, to ultimately improve accessibility for patients.

3.4.3. Standardised Guidelines for Penile Rehabilitation

I think that some men are like, yeah, I don′t have sex. I don′t really have any libido… But you might experience penile shrinking. That means you can′t actually urinate standing up, like this is actually, this is about your function, your physical quality of life outside of sex. (Participant #20, Sexologist).

I would love to see patients referred for sexual health counselling as a routine part of that preoperative treatment, like as part of their pretreatments, like not just teaching them about the surgery, but a comprehensive sexual health assessment, you know. You see the pre-op nurse, you see a physiotherapist, you see a sexual health nurse. Just to cover the bases. (Participant #6, Nurse)

I have this pipe dream that I′d love for every patient to be given a free vacuum pump after surgery, for example, and I have heard of other prostate nurses who, through charity and grants, have managed something like that. So it′s something on my agenda for this year. (Participant #13, Nurse).

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to provide an in-depth insight into some of the challenges HCPs face in the delivery of sexual well-being support to prostate cancer patients and identify areas for change to improve care delivery and patient outcomes. We interviewed HCPs, including nurses, pharmacists, sexologists and a physiotherapist and a medical oncologist, who were all involved in providing information and/or support to prostate cancer patients (and their families) relevant to their sexual function and well-being. We identified a number of challenges and issues experienced by HCPs which complicated care delivery, including the necessary reliance on other HCPs to facilitate/support care, logistical issues (e.g., having private space available for appointments), the involvement of partners/family, regional/rural issues and patient-specific barriers (e.g., patients’ financial circumstances). HCPs also recommended several priority areas in which change to the current system: (1) increased education for treating specialists and GPs on sexual well-being in survivorship, (2) greater prioritisation and resourcing for multidisciplinary care teams in survivorship and (3) the creation of standardised penile rehabilitation guidelines.

As similarly reported in other Australian-led research with HCPs on the provision of sexual well-being support in cancer [22], participants in the present study described sexual impacts of cancer as more than a change in sexual function and fertility; rather they encompassed a range of biopsychosocial elements, including mental health, masculinity, body image and relationships with others. HCPs in this study considered sexual well-being as an important aspect of prostate cancer survivorship, which should be routinely discussed with patients throughout their journey. This increased awareness for the importance of addressing sexual well-being in survivorship care likely reflects the ongoing research that identifies sexual issues as one of the biggest unmet needs among men with prostate cancer [4, 5, 17, 18, 23]. The recently published Guidelines for Sexual Healthcare for Prostate Cancer Patients [7] stress the importance for all clinicians to consider the biopsychosocial impacts of prostate cancer on sexuality and counsel patients accordingly. In line with this, HCPs in the present study (particularly nurses and pharmacists) felt strongly that further awareness and education, particularly for clinical specialists (i.e., urologists, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists) and GPs, was required to improve patient outcomes, as well as mitigate some of the challenges they experienced when providing support.

One of the most difficult challenges HCPs faced in delivering sexual well-being support was the necessary reliance on other HCPs for providing and facilitating care. The success of this shared care approach was largely impacted by the level of importance that HCPs placed on sexual well-being in care, as well as their knowledge of treatment/support options. Nurses in this study often described having to educate treating specialists themselves to ensure that patients were referred to their service and provided access to erectile dysfunction treatments—an account which was triangulated by the medical oncologist who was also interviewed. The provision of further training to increase awareness of the biopsychosocial impacts on sexuality prostate cancer can have, in addition to treatment and support options to manage these impacts, was strongly recommended by participants in the study, especially for treating specialists and GPs. As per the recommendations in the sexual healthcare guidelines for prostate cancer patients, clinicians involved in patient care should discuss all available erectile dysfunction treatment options with patients, including PDE-5 inhibitors, ICI therapy, vacuum erection devices and penile implants [7]. While most of the HCPs in the study described feeling confident in fulfilling this role, they often felt that many treating specialists and GPs lacked the knowledge to support these discussions and assist in facilitating treatment where necessary. Research suggests that HCP avoidance of discussing sexual well-being is often due to a lack of education and confidence in discussing a patient’s sexual well-being, in addition to a lack of time available in appointments [19, 24, 25]. To ensure HCP participation in further education/training, it must be accessible, concise and relevant. One solution may be the provision of a brief, mandatory e-learning module tailored to treating specialists and GPs who manage prostate cancer survivorship care. A recent pilot study conducted in the United Kingdom with 44 HCPs involved in prostate cancer care confirmed that this strategy was acceptable and effective in improving HCP knowledge and understanding of sexual issues after prostate cancer and increased HCP confidence in discussing sexual well-being with patients [26]. Whilst further research on this intervention is required, results are promising, and such training modules warrant consideration for adaption and integration into the Australian healthcare context.

Other recommendations made by HCPs in the study were for a more standardised treatment and care pathway for patients—both in regard to the referral and inclusion of allied health professionals for pre- and posttreatment care, and for the development and adoption of penile rehabilitation clinical guidelines. Penile rehabilitation is defined as interventions used to restore penile health and erectile function [27]. Currently, there are no standardised treatment regimens or clinical guidelines for penile rehabilitation for prostate cancer patients in Australia, though typically involves the use of PDE-5 inhibitors (to restore blood flow to the pelvis/penis), vacuum erection devices (to prevent atrophy) and, if desired, erectile dysfunction treatments such as ICI therapy (to restore erections) [27].

There is a plethora of evidence to suggest that penile rehabilitation after treatment improves patient outcomes in both their physical function and quality of life [28–31], though a significant proportion of the research focuses on postprostatectomy patients [31]. Further research studies, including randomised controlled trials, are required to better inform treatment algorithms and recommendations for both surgical and radiation treatment modalities. Regardless, given many HCPs are recommending and/or implementing penile rehabilitation protocols as part of routine care, standardisation of guidelines informed by the currently available evidence is recommended and will likely improve patient care delivery and outcomes.

HCPs in the present study also suggested that allied health professionals, particularly sexual well-being specialists (i.e., specialist nurses, pharmacists, physiotherapists and sexologists) and mental health experts, should also be involved from diagnosis onwards to both facilitate and support patient’s rehabilitation and survivorship care. There is growing evidence and support for specialised nurse-delivered survivorship care improving patient outcomes [32–34]. Australian survivorship care has seen an increasingly prominent role played by government and charity-funded prostate cancer specialist nurses, with demonstrated competency in managing aspects of survivorship care. However, the number of specialist nurse positions falls well short of what is required to guarantee all men with prostate cancer have access to this support. With further resourcing, there is an opportunity for specialist nurses to assume a more central role in sexual survivorship care, linking in with other HCPs and taking advantage of other available services.

There are several limitations to the present study which should be considered when interpreting these results. First, the sample of HCPs was somewhat limited such that only one specialist clinician (a medical oncologist) was recruited into the study, despite significant efforts to recruit urologists and radiation oncologists. In addition, whilst our sample did include two sexologists, we were not able to recruit any other HCP who specialised in counselling, such as psychologists. While qualitative research does not necessarily aim to be representative and generalisable, inclusion of these professionals would have offered greater diversity in perspectives and contributed to the understanding of issues/challenges faced by HCPs when providing sexual well-being support. Furthermore, this study was limited to practitioners working in Australia, and therefore, the experiences and perspectives of the HCPs involved reflect the Australian healthcare system. Differences in HCP roles and responsibilities, as well as healthcare and treatment options available to patients, may differ in other settings, particularly those without government-funded medical care.

5. Conclusions

This study utilised a qualitative approach to provide in-depth insight into the issues in prostate cancer sexual well-being survivorship care delivery from the perspectives of the HCPs providing such care. HCPs face numerous challenges in providing sexual well-being care to men with prostate cancer, many of which can be addressed by increasing the awareness of the importance of sexual well-being as part of high-quality survivorship care, at both the HCP level and through the greater healthcare system at large. Key priority areas for change, as informed by the HCPs in this study, include the creation and standardisation of penile rehabilitation guidelines, increased training for treating specialists and GPs and greater access to and involvement of nursing and allied HCPs with expertise in sexual health as part of routine care both pre- and posttreatment.

Ethics Statement

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Southern Adelaide Clinical Human Research Ethics Committee in November 2023 (LNR/23/SAC/146).

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The authors confirm that all participants consented to the inclusion of their deidentified quotes being used for publication.

Disclosure

The funders had no role in the design or conduct of the study including the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript or decision to submit for publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Megan Charlick: conceptualisation, methodology, data collection, validation, formal analysis, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing and project administration. Kerry Ettridge: writing–review and editing. Tenaw Tiruye: writing–review and editing. Michael O’Callaghan: writing–review and editing and project administration. Sally Sara: writing–review and editing. Alexander Jay: writing–review and editing. Kerri Beckmann: conceptualisation, formal analysis, writing–review and editing and funding acquisition.

Funding

This work was supported by the Hospital Research Foundation (grant number: 2022-CP-IDMH-018). Authors K.E. and K.B. are currently supported through the Cancer Council SA’s Beat Cancer Project, on behalf of its donors and the State Government of South Australia through the Department of Health and Wellbeing (2024–2026).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to all the participants who expressed interest and participated in the study, as well as the organisations and colleagues who assisted in study advertisement and recruitment. They would also like to thank the participants of the consumer advisory group who willingly shared their experiences, opinions and feedback on the study design, materials and findings.

Supporting Information

The supporting information provided includes the interview guide used in this study and the participant profile (supporting table 1).

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical concerns.