What is “Coaching” in Interventions for Patients in Cancer Care Research? A Systematic Scoping Review

Abstract

Objective: Cancer has an impact on psychosocial well-being as well as on mental health. Coaching increasingly appears as a source of psychosocial support to cancer patients. However, we currently lack a clear framework for coaching in that context. The present review aims to better define the concept of coaching in interventions for patients in cancer care research, as well as to synthesize frameworks, techniques, and providers.

Methods: A conceptual scoping review based on PRISMA was performed on studies focusing on coaching and cancer published in peer-reviewed journals until November 2024. Studies on coaching and cancer were systematically extracted from five online databases and then screened.

Results: A total of 237 studies were included after screening. Less than 15% of the studies provided an explicit definition of coaching. Six coaching categories were identified based on their goal, in addition to a general form of coaching. Coaching in cancer care occurs during the acute treatment phase as well as during the posttreatment phase. Most providers were healthcare professionals, despite an important heterogeneity. Techniques were sorted into 9 sets of techniques implemented in coaching interventions, including goal setting, providing support, and self-regulation.

Conclusions: This review provided structure to the field of coaching in cancer. It also showed that defining a field only on the word “coaching” does not appear sufficient to reflect the current heterogeneity. Consequently, there is a necessity for the field to clarify its theoretical frameworks, targets, and intervention components to increase the necessary reproducibility and cumulative knowledge.

1. Introduction

Cancer, a group of diseases characterized by the rapid creation of abnormal cells that grow beyond their usual boundaries, is a potentially life-threatening disease with an increasing incidence [1]. Cancer patients’ life expectancy is currently improving [2], but patients still face an important cognitive, emotional, and social burden [3]. Surviving patients also have to face different psychosocial challenges, such as returning to work [4], adjusting to neurocognitive dysfunction [5], or fear of recurrence [6], while maintaining or adapting their identity [7]. Research is increasingly focusing on stepped-care approaches, to provide low- to mid-intensity psychological support to patients who do not need high-intensity support (with mixed results, see [8]). In the last two decades, a growing number of psycho-oncology studies and interventions have relied on “coaching” approaches and tools to provide such (cost-)effective support to patients in addition to existing ones.

Initially, coaching was associated with work-oriented challenges and focused on supporting individuals to thrive in their work and address work-related issues [9]. It was meant as a task or attitude performed by the managers, “coaching” their employees. This approach of coaching quickly expanded to accompany self-defined goals in general, whether in the work context or outside of it. Subsequently, coaching was defined as a collaborative relationship that focuses on goal-setting designing solutions, or attainment processes [10]. It is about improving the achievement of self-congruent goals and promoting conscious self-change and self-development [11], as well as attaining better well-being using the individual’s resources [12]. In that context, coaches are seen as learning facilitators that support individual processes.

Such a definition encompasses several approaches and theories, each addressing different facets of human experience and behavior [13, 14]. Some of the most common forms are as follows: executive coaching focusing on performance and well-being enhancement at work [10]; stress (self-)management coaching to help individuals cope with their stress (inside and outside of work) [15, 16]; and life (or personal) coaching to improve the achievement of personal life goals [17]. In that regard, it can be considered as one operationalization of positive psychology, including through a focus on growth and change [18], as well as the reliance on techniques that originate from that field [19].

Yet, there appears to be no consensus on the definition, conceptualization, and operationalization of coaching as a field [11]. Moreover, it is acknowledged that coaching has no clear set of skills, training, or theories that would unify the practice behind the word [20]. This issue stems from the fact that coaching has organically and incrementally grown while being at the crossroads of several fields (e.g., behavioral sciences and organizational studies) [10]. Although often cited, coaching, however, remains an ambiguous field that requires structure. Several reviews have tried to provide such necessary structure in coaching, with various fortunes [10, 11, 21].

Coaching has also been applied to chronic diseases—including cancer—often under the label of “Health and Wellness Coaching” (HWC) [22]. HWC is a form of coaching targeting the improvement of health behaviors (e.g., physical activity and diet). Recent reviews on HWC have highlighted its potential for behavioral and psychosocial outcomes [22, 23]. However, HWC only reflects one delineated instance of “coaching” in cancer care, and numerous coaching studies in cancer were therefore not included, leaving them not fully understood and categorized. As such, cancer coaching studies targeting, for example, self-management [24], education [25], or motivational interviewing [26] are not yet included. This impairs a proper definition and delineation of coaching in the cancer context.

In a broader context of a hard-to-define field, coaching often flirts with pseudoscience and must therefore be well-defined, which includes an evaluation of coaching practices [27]. Because cancer coaching is expected to grow in the coming years, it appears therefore necessary to provide a framework for future practice, research, and evaluation in the field. Therefore, the present work proposes to make a conceptual systematic exploration of what is referred to under the umbrella term of “coaching” in cancer care.

1.1. Objectives

The present review aims at structuring all literature that refers to itself as “cancer coaching.” The objectives of this scoping review are twofold. First, the goal is to list all studies that combine the labels of “cancer” and “coaching” to explore what definition was used for coaching in that context and see if categories or distinct fields of research can be defined. Second, and beyond the sole term of coaching, the goal is to list the techniques and modes of delivery in these studies, to have a comprehensive collection of what is currently performed. This would provide a necessary overview of how coaching is actually implemented.

2. Methods

The present study consists of a systematic scoping review [28] with specific attention given to a conceptual review of what “coaching” entails in cancer research [29]. This approach was chosen because it provides a framework to explore and structure existing research while accounting for its lack of current structure (impairing further exploration, e.g., meta-analysis of efficacy). The present work is therefore seen as a necessary step to establish a structure for future works and reviews.

The present review follows the PRISMA extension for scoping review [30].

2.1. Protocol and Registration

The protocol has been registered in the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/7yce4). The sole deviation from the protocol was to not include the efficacy of the coaching and the quality assessment of each study in the present review. This was decided based on the large number of studies and their important heterogeneity which first requires structure before synthesis and in favor of a conceptual focus on the included studies.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria, Information Source, and Search

The focus was on studies that empirically associated cancer and coaching. Therefore, studies were included if they (1) address both “cancer” and “coaching” (as broadly defined above), (2) were empirical interventions on cancer patients, (3) were published in a peer-reviewed journal or book, and (4) were published in English, irrespective of their publication date or design (e.g., feasibility study, randomized control trial [RCT]). Studies were excluded if they addressed separately “coaching” and “cancer” and did not contribute to the understanding of their combination. Studies were also excluded if they did not focus on the treatment or the survival phase of cancer (e.g., focusing on cancer screening) or focused solely on sports coaching, as the present focus is on psychosocial coaching. Only studies where the patients were targets of the intervention were included (alone or with their informal caregivers or partners).

The studies were retrieved from five key online databases in the fields of medicine and psychology: Embase, PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. As the objective was to synthesize published studies, no attempt was made to explore the grey literature. This extraction of online databases was performed in December 2022 (updated in November 2024) and focused on all available studies published until that moment. Keywords to retrieve studies are presented in Appendix 1. Previous existing reviews were hand-searched to identify additional references.

2.3. Selection of Sources of Evidence

Identified records were merged using EndNote, and duplicate records were removed using a deduplication method [31]. Using an online spreadsheet app, two researchers (P.G. and A.M.) each independently screened all titles and abstracts (yes/maybe and no) based on the inclusion criteria. Disagreement was solved through consensus. Full texts were screened by two reviewers (P.G. and A.M.). The update from 2024 was performed by the first author (P.G.). Following PRISMA recommendations, the reason for exclusion was only mentioned at the full-text stage.

2.4. Data Charting Process and Items

A data extraction spreadsheet was used to extract information on study description; participants’ characteristics; study design; study objectives; coaching approach; implementation of the coaching component; and coaching intervention. Data extraction was shared by two authors (P.G. and A.M.).

2.5. Synthesis of Results

Based on existing recommendations in the reporting of scoping reviews, the results were synthesized narratively and with tables [28, 32]. A first synthesis focuses on the definition and approaches of cancer coaching. We regarded as a “definition” any statements or indications within the introduction and methods sections that elucidate the authors’ conceptual understanding of coaching, while deliberately excluding explicit descriptions of the coaching activities implemented in the intervention. These elements of definition were then thematically synthesized by exploring the common elements among the different studies, to build a synthesized definition. A second focuses on the content of the interventions. Given the large number of studies available, a two-step approach was used to organize the existing literature. In Step 1, studies were sorted based on how the authors labeled the coaching component in their paper to form a preliminary series of categories. Based on that first categorization, main group of studies could be identified, relying on the common target of these coaching approaches (e.g., on health behaviors and decision-making) rather than the providers (e.g., “nurse coaching” and “digital coaching”). In Step 2, uncategorized studies (i.e., studies that only mentioned “coaching” or “coaches,” as well as studies that did not fit with the definition of the category that was first assigned based on their label) were then assigned to one category to then refine and make sense of each of them. A thorough analysis then led to forming a definition of each category. Following that, the components of the coaching interventions (e.g., providers, focus, and techniques) were synthesized for each coaching category based on cross-referencing elements of the extraction sheet.

To relate to existing frameworks in intervention techniques, the present study relied on the Behavior Change Technique (BCT) Ontology, which is a work that aims to unify definitions of all behavior change intervention components by providing a structured ontology (see [33]). It consists of a comprehensive framework of 20 higher level groups of BCTs, each with its identification code, wherein most (if not all) BCTs can be grouped. This ontology is part of a larger creation of complementary ontologies aiming at providing a clear structure to behavior change intervention studies to facilitate their comparison [34].

The synthesis was performed by the first author, with regular iterative reports, discussions, and adjustments made with the other coauthors to improve validity and clarity.

3. Results

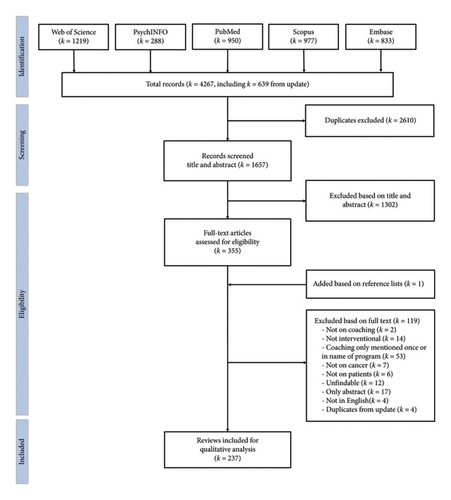

At first, a total of 4267 studies were included from the different databases (see Figure 1). After duplicate screening, 2610 studies were excluded, followed by 1302 based on title and abstract screening. This left 355 studies for full-text screening, among which 119 were excluded and one included. This led to the inclusion of 237 studies in the present review.

Because of the high number of studies (k = 237), the summary of each study can be found in Appendix 2. Due to the journal’s constraints, not all studies could be cited directly in the text and only representative studies were therefore cited. Consequently, the exhaustive reference list of the studies included in the present review is displayed in Appendix 3.

Studies were mainly originating from English-speaking high-income countries (75.5%), i.e., 138 from the United States (58.2%), 18 from Australia (7.6%), 12 from Canada (5.1%), and 11 from the United Kingdom (4.6%). The rest mainly originated from continental Europe (15.6%) and East-Asian countries (8.0%). They mainly focused on adults (89.5%), the rest focusing on either children, adolescents, or young adults, or a combination. Most studies focused on various forms of cancers taken together (50.6%), whereas the rest focused on a specific form of cancer, among which the most common were breast cancer (23.6%), prostate cancer (5.1.%), lung cancer (3.8%), and colorectal cancer (2.5%).

As per our inclusion criteria, the designs of the studies were heterogeneous, ranging from feasibility studies to RCTs (see Appendix 2). Forty-seven different labels were used to define the design of the included studies, the most common being RCT (k = 103, 43.5%), pilot study/trial/test/RCT (k = 40, 16.9%), and feasibility study (k = 27, 11.4%).

3.1. Definitions of Coaching

The first goal was to explore the definitions of coaching used in the included studies. Less than a fifth of the included studies (k = 34, 14.4%) provided an explicit definition of coaching or mentioned a coaching framework in their work. Different elements mentioned in these definitions can be used to provide a synthesis of the definition provided.

Coaching appears as a patient-centered [35–37], individualized [38–44], relational, and dialectic [36, 37, 45–47] support [36, 38–40, 46–51] to cancer patients. Its final goal appears to be the improvement of the patient’s wellness [36, 40, 45], well-being [37, 40, 50, 52], and quality of life [53], with a strong emphasis on increasing self-management [26, 35, 36, 43, 45, 52, 54, 55] and (self-)empowerment [35–37, 47, 50, 54, 56–60], as well as self-efficacy [35, 38, 50, 51, 54, 59] and self-confidence [59]. As such, coaching seems to be relying on goal-setting [36, 37, 47, 51, 61], goal achievement [35, 41, 51, 53, 59, 60], and the engagement in and maintenance of behavior change [35–38, 40, 42, 44, 45, 52, 55, 60, 62]. It is also seen as relying on motivational work [38, 40, 43, 60] and education [36, 49, 54], based on the patient’s own resources [51, 59], strengths [37], and potential [53]. Regarding its theoretical anchorage, some authors support that coaching is evidence-based [43, 45] but mostly theory-based [26, 38, 41, 44, 51, 55, 62], notably by relying on sociocognitive theory or the transtheoretical model of change. Finally, coaching is mentioned as being result-oriented [37], which can in certain cases facilitate the transition to postcancer life [39] or guarantee continuity during treatments [36]. The providers of coaching are often explicitly referred to as coaches [35–38, 40, 45, 47, 48, 53, 60, 61] and are seen as partners [49] who could be peers [56].

3.2. Categories of Coaching in Cancer

Table 1 displays the seven different categories of coaching that were identified based on the included studies (see Appendix 4 for the 20 original categories identified in Step 1). Six have specific targets and a seventh (i.e., General and Multifaceted Coaching) has a broader scope. The six specific categories of coaching interventions target, to different extents, a biopsychosocial challenge raised by the disease. One study was set aside from other studies, as the coaching component’s main aim was to promote the participation of patients in clinical trials [63].

| Category of coaching | Goal |

|---|---|

| Health and Wellness Coaching k = 92 | Encourage and guide cancer patients toward healthier behaviors, with a major emphasis on increasing physical activity and improving dietary habits. Health coaching typically assists patients in identifying and pursuing behaviors that they themselves perceive as important for their well-being or that are defined as healthy |

| Self-Management Coaching k = 49 | Empowering individuals to effectively manage their health conditions. It involves providing individuals with the tools and support necessary to take active control of their disease, as well as the side effects and consequences of treatments. It covers a wide array of aspects, including medication, fatigue, pain, or sexuality |

| Communication and Decision Coaching k = 32 |

|

| Mental Health and Well-being Coaching k = 27 | Supporting the mental well-being of patients, addressing issues like anxiety, depression, and fear of recurrence |

| General and Multifaceted Coaching k = 26 | Not specifically target a single component of care but instead address a mix of physical, mental, and emotional health aspects. It reflects a more holistic approach of addressing patients’ needs, sometimes including a personalized approach |

| Life Coaching k = 6 | Supporting patients’ overall growth based on their personal goals and needs. Using individual resources to meet challenges in their lives and increasing the self-confidence through the definition, pursuit, and attainment of self-selected goals [51] |

| Cognitive Coaching k = 4 | Enhance cognitive abilities that might have been affected by cancer treatments (e.g., working memory, attention, processing speed, and executive function). It aims at maximizing the effectiveness of the cognitive training program and ensuring participants’ engagement and progress |

- Note: One study did not fall into a category [63].

3.3. Integration of Coaching in Intervention Design

Although all studies needed to have a coaching component to be included in the present review, the centrality of the coaching component varied importantly. As such, it appears that most studies were coaching interventions (k = 98; 41%)—where coaching was the main or only component of the investigated intervention [64]; e.g., [26]—or part of multicomponent interventions studies (k = 102, 43%)—where coaching held equal importance to other components (e.g., accompanying an education module). In these studies, the coaching was therefore integrated alongside other components (e.g., alongside a nutritional intervention [65]; or in addition to an educational module [66]). The last set of studies consisted of studies where coaching was only present to support the main intervention of studies. This took two distinct forms, based on how studies were reported. The first was when “coaches” were the ones performing the intervention (k = 6; 3%), often with no clear specification as to why they were labeled as coaches (e.g., [67, 68]). The second consisted of studies where the coaching component was only there to support the main intervention (k = 31; 13%), notably to ensure compliance with the intervention or to solve problems encountered (e.g., problems with the online self-help platform [69]).

3.4. Coaching Intervention in the Cancer Continuum

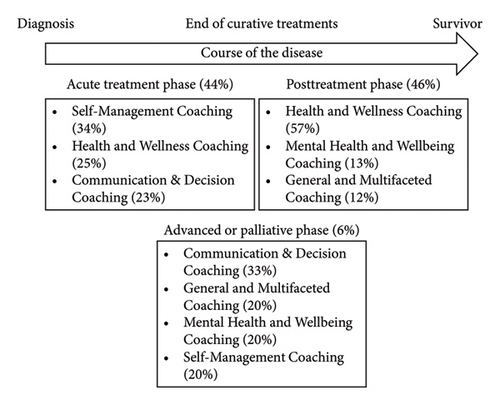

The interventions focused on the different phases of treatments, with a balance between the acute phase of treatments and the after treatments. Appendix 5 displays in detail the interplay between the phases of treatment and the categories of coaching, and Figure 2 presents a visual summary. A large proportion of coaching studies focused on the acute phase of treatments when patients undergo active treatment (k = 104, 44%), including one study specifically on reoccurrence [70] and another on chronic leukemia [54]. The coaching approaches during treatments were mainly focusing on Self-Management Coaching (34%), HWC (25%), and Communication and Decision Coaching (23%). Studies focusing on the period after main treatment were also frequent (k = 108, 46%), with studies focusing on cancer survivors, survivors with maintenance chemotherapy [71], and survivors in active surveillance [60]. Most of these posttreatment studies relied on HWC (57%), Mental Health and Wellbeing Coaching (13%), and General and Multifaceted Coaching (12%). A less frequent set of studies focused on more advanced and palliative (k = 15, 6%) forms of cancers, with a particular emphasis on Communication and Decision Coaching (33%), followed by General and Multifaceted Coaching (20%), Mental Health and Wellbeing Coaching (20%), and Self-Management Coaching (20%). Finally, a minor set of studies (k = 10, 4%) considered all kinds of cancer patients together.

3.5. Coaching Providers

Coaching in the included studies came from a variety of providers, including both professionals and nonprofessionals, trained and untrained individuals, and even automated or virtual systems (e.g., chatbot). However, most coaches came from a healthcare background (k = 106; 45%). This included nurses (k = 54, 23%), physiotherapists and physical therapists (k = 10, 4%), health educators (k = 8, 3%), occupational therapists (k = 5, 2%), psychologists (k = 3, 1%), dietitians (k = 2, 1%), or a combination of different healthcare professionals (k = 22, 9%). In several instances, the coaching was also provided by students (k = 12, 5%), mostly in training in medical professions. In some physical activity studies, the coaches were physical trainers (k = 4, 2%). Coaching was also performed by peers (k = 16, 7%) and informal caregivers (k = 1). The place of digital platforms providing coaching through apps, automated answer systems, or virtual agents was also nonnegligible (k = 23, 10%).

The rest of the studies were less clear. Coaching was performed by “coaches” in 26 studies (11%), often without clear specifications as to what was their initial training. The same issue was encountered when studies relied on research staff (k = 10; 4%) and laypersons (k = 4; 2%). In the last set of studies, it was either unclear (k = 11, 5%) or not mentioned (k = 20, 8%) who provided the coaching.

Appendix 6 displays the providers by the phases of the disease. Appendix 7 displays the providers by coaching categories.

3.6. Typology of Coaching Techniques

The last goal of the present review was to understand the techniques used in the coaching interventions.

In the included studies, an important variety of techniques are reported as part of the coaching components of the interventions. These techniques were inductively structured into 9 types displayed in Table 2. These 9 types of techniques are mainly focused on behavior change, from the initial phases of Education, Goal Setting, and building Motivation to Training and providing Feedback during their implementation. As mentioned, we refer to the BCT Ontology codes to integrate the present review in existing frameworks [33].

| Type of techniques | Definition | Examples | Related Behavior Change Technique (BCT) Ontology groups |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goal setting | Techniques related to defining specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and timely (SMART) targets. This involves setting behavioral objectives, formulating a plan of action, and discussing outcomes |

|

|

| Barrier identification, planning, and Problem-solving | Techniques that focus on recognizing obstacles and devising solutions for overcoming them |

|

|

| Self-Management & Monitoring | Techniques centered around tracking and reviewing personal data or behaviors related to health, symptom, and side-effect management and being able to act accordingly in response |

|

|

| Motivation | Techniques that involve building a patient’s motivation to change or maintain health behaviors |

|

|

| Self-regulation | Techniques used to develop better skills in self-regulation, including emotion and stress management in order to increase mental well-being |

|

|

| Feedback & Reinforcement | Techniques focused on providing patients with constructive feedback on their performance and reinforcing progress made toward their health goals |

|

|

| Education | Techniques involving the sharing of knowledge and information to assist patients in understanding their health condition, its management, and its implications |

|

|

| Support | Techniques that aim to foster a supportive relationship between the coach and the patient, providing encouragement, empathy, and guidance throughout the process |

|

|

| Training | Techniques supporting the acquisition, understanding, and application of knowledge, skills, and competencies. Beyond simply providing patients with educational resources, it ensures teaching them how to use them, and guiding them in practicing the learned skills. |

|

- Guide how to perform behaviour BCT (BCIO: 007050) |

- Note: The related BCT groups originate from Marques et al. [33] and are mentioned to relate to the gold-standard ontology of BTC.

The correspondence shows that most of the coaching techniques can, to some extent, be related to BCT, with 14 of the 20 groups of BCTs present in the included studies. A particular emphasis is put in the included studies on Barrier identification, Planning, and Problem-Solving. This type of technique (which loosely relates to BCIO: 007001; 007090; 007168; 007150) appears to be at the core of coaching. It shows the importance of co-elaboration and collaboration in the coaching relationship to find an adequate solution tailored to the patient. The importance of that collaboration was often highlighted in the included studies as a key component. This also includes particular attention to support techniques, in providing emotional support, reassuring, and using active listening.

However, the overlap with the BCT Ontology is not complete. For example, the important work on motivation (e.g., motivational interviewing), even though tied to Goal Setting, holds central importance in coaching studies but is less explicitly included in the BCT Ontology. Self-Management & Monitoring, if tied to Monitoring BCT (BCIO: 007017) goes beyond it as it includes an important array of specific behaviors that are specific to diseases and cancer, notably through symptom and side-effect management (e.g., [72]), as well as how to ask for questions or help when necessary, based on the said monitoring (e.g., [43]).

One notable element to highlight regarding the techniques included is that most of them are used by the coach during the sessions with the patients, but these techniques can also be used by the patients outside of that setting. For example, Goal Setting through SMART goal definition can span beyond the sole coaching moment and be used by patients in other contexts [69]. The self-regulation techniques, while used during the coaching sessions, are also aimed at being used outside of that setting [67].

4. Discussion

The present scoping review explored coaching in cancer to address the heterogeneity of the field and clarify what is coaching in cancer in interventional studies as well as to provide a framework for future studies and allow their meta-analysis. Consequently, this paper tried to clarify the definition of coaching, provide a categorization of the areas of coaching, structure the techniques that are often used in coaching, and provide a picture of the included interventions as to who provides coaching, the integration of the coaching component into the interventions, and the moments of the cancer journey during which the coaching is present.

Coaching in cancer is a patient-centered, individualized, relational, and dialectic form of support aimed at enhancing the wellness, well-being, and quality of life of cancer patients. It focuses on goal-oriented (behavior) change to empower patients throughout their cancer journey. Subsequently, coaching can be seen as a facilitating process focusing on initiating, supporting, and consolidating change. The coaching process is geared toward working on patient’s needs, by helping them clarify, define, and attain realistic goals, using their resources. Coaching may have various targets that are challenged by the disease, which include the improvement of health behaviors, self-management, communication and decision processes, mental health, or attainment of life goals. It can be a stand-alone intervention but can also be present to support other interventions or programs. Coaches are the providers of coaching and can be healthcare professionals, lay individuals, peers, or even digital tools. They rely on a vast array of techniques, including goal-setting, problem-solving, self-regulation and -management, education, and support.

This definition reflects the heterogeneity of the coaching field but also that it seems to be held together by common principles. The most common principle of coaching in cancer is the support of personal growth, empowerment, behavior change, and well-being through the activation and improvement of the patient’s resources and skills, in various domains (e.g., health behaviors, self-management, communication, and decision-making). As such, coaching probably seeks to provide support through an alternative to psychological support. This is also reflected by those who provided coaching in the included studies, where psychologists were rarely present. This observation echoes the works attempting to identify the boundary between coaching and mental health counseling practices, ending up pointing them on a continuum [73]. In that context, coaching interventions in cancer can be seen as first-line interventions that are “briefer, problem-focused and targeted at improving wellbeing in nonclinical populations.” ([74], p. 288).

This seemingly clear definition must however not hide the fact that the included studies are highly heterogeneous on different intertwined levels. At this stage, the important variability in definitions, categories, techniques, and coaching providers interrogates the assumption that coaching can be considered as a unified concept and practice.

The difficulty in defining and clarifying what is coaching starts with the difficulty that the word “coaching” appears polysemous in the included studies. On the one side, we can observe research labeling itself as “coaching” research, relying on some form of coaching framework, provided by people defining themselves as coaches [13]. On the other side, we see various studies using “coaching” interchangeably with “support,” suggesting a generic form of aid or assistance without a clear specific framework. In between the two, there were studies where “coaching” implies a certain structured form of patient support but still lacks a concrete definition or reference to a cohesive theoretical coaching framework (related to coaching research or not). This confusion underscores an urgent need for future research to articulate what is meant by “coaching” to distinguish between these varied uses. The implicit and undefined use of “coaching” by some authors—while not necessarily indicating a lack of theoretical underpinning for their study as a whole—contributes to an ambiguity that hinders the precise demarcation and evaluation of coaching in cancer care.

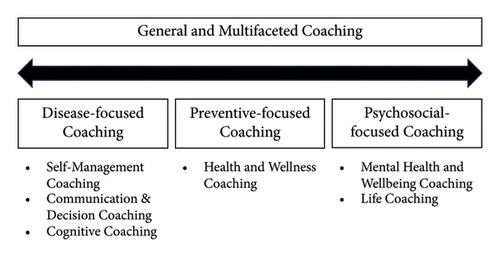

Seven categories of coaching approaches were identified through the present review, from the known HWC to more discrete instances, such as Cognitive Coaching. To provide a framework for future studies, we propose that these categories can be further structured around a continuum of patient-centered coaching interventions (see Figure 3). On the one end, coaching studies focus more on the challenges that the patients face due to the disease and its management, as well as the relationship with the healthcare professionals. On the other end, coaching studies focus more on the psychosocial challenges of the patients, which are linked to the disease, but not exclusive to it. In between, HWC studies focus on increasing the patients’ physical recovery from the disease, but also increasing protective factors against potential reoccurrence (including stress management). This continuum structure provides the opportunity to consider that coaching interventions for cancer patients, while always patient-centered, have varying degrees of focus on the disease. The end of disease-focused coaching is tied to the disease while psychosocial-focused coaching can be related to the disease but could be implemented without the patient being ill.

Beyond the sole label, we can identify that coaching is a set of techniques that a person can take to support behavior change. That behavior change lens combined with the important heterogeneity of BCTs included shows that coaching is a polymorph form of support. Consequently, the need for coaching interventions (and particularly in research) should be to clarify which BCTs they are based on. For now, this is not clear. The present review provided a structure to help future studies in reporting a clear(er) set of definitions of the BCTs included to help replicate coaching interventions and provide the opportunity to better assess their efficacy (and efficiency) [75]. Relating to existing frameworks of BCTs might also help in linking coaching research to broader research, and not focusing only on the coaching side of evidence.

The fact that coaching is performed by different kinds of individuals, from laypeople to healthcare professionals, also fuels the observation of heterogeneity in coaching and the necessity to clarify how coaching interventions are delivered [76]. However, the important place of healthcare professionals does suggest that the people providing coaching should have some form of adequate knowledge, understanding, and training that allows them to be close to the experience of the cancer patients. Such observation has been supported by a recent review on the training of healthcare professionals in health coaching, highlighting the benefits (and challenges) of healthcare professionals in providing coaching to patients [77].

A last observation is the striking absence of return to work in the present review. Only two included studies emphasized coaching to support return to work [41, 78]. Despite an increasing focus on research, policies, and practices, return to work remains a key issue in cancer survivorship, which calls for new approaches to address it [79, 80]. This is particularly necessary since existing evidence shows the limited to absent impact of existing interventions [4, 81]. In that context, coaching can play an important role, notably because it takes its roots in organizational contexts. As such, future studies could provide fruitful synergies using (return-to-)work-related tools adapted to the specificities of the cancer context to open new avenues of research.

4.1. Study Limitations

The present review did not focus on the efficacy of coaching interventions. Its main motive was to create a framework for coaching studies in the face of a too-heterogeneous field that lacks adequate categories to allow comparability and any cumulative approach [28]. Therefore, it included all studies with interventional components, regardless of what they measured. Consequently, the present review does not conclude on the (in)effectiveness of coaching in cancer. Because of the qualitative nature of this summary and the significant number of studies included, other authors could also have produced a different framework than the one provided in the present paper, which reflects our reading of that field.

4.2. Clinical Implications

Cancer coaching as a “discipline” can hardly be summarized homogeneously. The categories of coaching displayed in Figure 2 provide a clear framework on how coaching can be implemented, based on the target. It should serve as a base for coaching intervention practices to call for a clear goal definition and a subsequent adapted requirement definition (e.g., having the necessary knowledge of the disease). The focus on types of techniques should also help define clearly what the coaching intervention implemented and the expected active component on which it relies. More broadly, the present review has shown the necessity to using the adequate label when creating a coaching intervention and to interrogate its theoretical underpinnings, as well as its potential overlap with psychological care.

5. Conclusion

The present work aimed at providing a framework for future studies in cancer coaching and a founding ground for them. The heterogeneity in the field, the challenges in defining coaching, the categorization of coaching, and the insights into techniques and approaches contribute to a complex but rich landscape. The direction for future research should involve a clearer use of the “coaching” word and what it entails, a closer examination of the underlying techniques used, and efforts to assess the efficacy of coaching in various contexts. It underscores the need for clarity, structure, and collaboration within the field to build upon this foundational understanding and create meaningful coaching interventions for cancer patients.

Disclosure

The protocol for this review was first posted on OSF (https://osf.io/7yce4) and relayed on the university portal https://researchportal.vub.be/en/publications/what-do-we-refer-to-as-coaching-in-cancer-research-a-scoping-revi.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

All authors (1) have made substantial contributions to the conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) have been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; (3) have given final approval of the version to be published; and (4) have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This work was funded by the Chair on Coaching and Cancer (Leerstoel Coaching & Kanker) at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, funded by the Belgian Cancer Foundation (Stichting Tegen Kanker—Fondation contre le Cancer) & Candras Foundation.

Acknowledgments

P.G., R.T., and E.V.H. were members of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) until the end of September 2023.

Supporting Information

Appendix 1: List of the keywords used to retrieve articles on online databases, as well as the research equation for each platform. Appendix 2: PDF file of the Excel sheet displaying all extracted information of the included studies. The present review is based on that table. Appendix 3: Complete list of references of the included studies (too long to be included in the manuscript). Appendix 4: Presentation of the two-step categorization of the coaching studies. Appendix 5: Crosstab between the phases of treatment and the categories of coaching. Appendix 6: Crosstab between the coaching providers and the phases of treatments. Appendix 7: Crosstab between the coaching providers and the coaching categories.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

All available information is present in supporting information.