Treatment Refusal by Cancer Patients: A Qualitative Study of Oncology Health Professionals’ Views and Experiences in Australia

Abstract

In some cases, against medical advice, a person with cancer decides not to undergo any conventional, evidence-based cancer treatments including chemotherapy, radiotherapy hormone therapy and others. Estimates for treatment refusal range from 2.6% to 14.55%. Refusing evidence-based conventional cancer treatments is linked to rapid deterioration, poor prognosis and a higher risk of premature death. This study aimed to explore oncology health professionals’ experiences and views on why patients refuse standard cancer treatments. We employed an in-depth qualitative research design, adopting a social constructionist framework. Fourteen health professionals in Western Australia (WA) with experience working in oncology were interviewed. Four themes were identified: ‘They want to do it their way’; ‘Keeping the door open’; ‘It can be draining’; and ‘Where to from here?’. We found that treatment refusal had a disproportionate impact on individuals, families, health professionals and the health system, including time spent engaging with patients contemplating refusing treatment. The issue is complex and multifaceted, with several motivations for treatment refusal. Statistics on 5-year survival rates need to be presented in a number of ways so that people understand what these statistics mean. General information on cancer regarding incidence, treatments and survival rates could be presented via social media so that we reach more people. Supports for oncology health professionals are needed including training to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout.

1. Introduction

Conventional, evidence-based cancer treatments include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, immunotherapy and targeted therapy [1]. In some cases, against medical advice, a person with cancer decides not to undergo any of these treatments [2, 3]. This is referred to as treatment refusal. Estimates for the proportion of people who refuse standard cancer treatments are inconsistent and vary across settings and diagnoses. A retrospective cohort study of people diagnosed with head and neck cancer from the United States reported 2.6% of people (2165) refused surgery [4]. Similarly, Fields et al. [5] found that 2.6% of people (509) diagnosed with stage 1 rectal cancer and 3.5% (2082) with stage 3 and 4 cancer refused surgery. A higher proportion of people (9.7%) diagnosed with cutaneous malignant melanoma in Italy refused treatment [6], and a recent retrospective case analysis study conducted in southern China found that between 2014 and 2020 24.55% of women diagnosed with breast cancer had refused treatment [7]. Khankeh et al. [8] suggest that these figures are conservative as many people abandon treatments in silence and are not recorded in the healthcare systems. Refusing evidence-based conventional cancer treatments can pose significant risk to patients and is linked to rapid deterioration, poor prognosis [9] and a substantially higher risk of premature death [10]. Older adults more commonly refuse evidence-based cancer treatments, and refusal is associated with greater rates of cancer recurrence and lower survival rates [11]. Treatment refusal also has implications for clinicians, as the demands on time needed to engage hesitant patients may increase the risk of burnout [12].

Primary reasons for treatment refusal include concerns about the efficacy of oncology treatment and side effects that result from treatment [13–15]. Other reasons include loss of control, hopelessness, denial about their cancer diagnosis, concerns regarding quality of life, strong beliefs in ‘alternative medicine’, depression, spirituality and the prior loss of peers to cancer [10, 16–18]. Plausible findings from systematic reviews on older adults refusing treatment were that lower levels of health literacy, lack of trust in medical systems, concerns about decreased quality of life and lack of social support may lead to refusal of treatment [11, 19]. However, the authors caution that the findings were based on studies that were retrospective and descriptive. A recent study conducted in Ghana found that extreme religious convictions and a belief in fatalism, as well as a poor relationship with health professionals, led to refusal of evidence-based treatment [20].

People refusing conventional treatments may use non–evidence-based treatments, commonly referred to as ‘alternative therapies’, that have limited or no demonstrated benefits for managing cancer [10, 16]. Generally, those who choose ‘alternative therapies’ over conventional treatments are younger, female, have more formal education and a higher-than-average socio-economic status [16]. In line with this work, Radley and Payne [21] previously offered a sociological model of understanding cancer treatment refusal. They proposed that treatment refusal is driven by two key factors: (1) an individual’s relationship to conventional medicine, and (2) competing ideologies. Specifically, Radley and Payne [21] suggested that individuals may see conventional medical treatment as a social instruction and a threat to their personal independence. They may prefer alternative treatments as they do not view conventional medicine as the authority in health or disease management.

While refusing evidence-based conventional treatment is not a new phenomenon among cancer patients, changes in the ways people access information may be influencing them to opt for potentially risky, non–evidence-based treatments [22]. People increasingly use the internet to research their illnesses, which enables them to take a more active role in their treatment and find practical advice [23]. However, the internet can also be used to access misinformation that promotes the use of non–evidence-based treatments for treating cancer [22]. These ‘alternative therapies’ represent a multibillion-dollar industry, and their products are aggressively promoted via the internet [22, 24]. Social media and internet blogs allow users to join groups of other people who share similar beliefs, resulting in the reinforcement of antiscience views, which often remain unchallenged [22, 25]. A study by Johnson et al. [26] reported on reviews by two cancer experts of 50 of the most popular social media articles on each of the 4 most common cancers. Of 200 articles, 32.5% (n = 65) contained misinformation.

Evidence-based approaches to encourage the use of standard cancer treatments over non–evidence-based therapies are urgently needed. However, currently, few efficacious evidence-based approaches to increase conventional treatment uptake exist. Developing a nuanced understanding of the relationship between health professionals and patients is seen as a key first step to develop such approaches [27, 28]. As such, this study aimed to explore oncology health professionals’ experiences and views on why patients refuse standard cancer treatments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

We employed an in-depth qualitative research design. Qualitative research focuses on individuals’ understandings and experiences and relies on people’s accounts and reflections rather than numerical data [29]. Qualitative research was advocated by Dias et al. [19] as imperative in understanding the reasons people refuse conventional cancer treatments. We adopted a social constructionist approach, as the study explored complex ideas and was grounded in applied settings. This approach acknowledges that meaning is constructed, and people’s interpretations of their experiences are shaped by culture and background. This approach has been successfully used in previous psycho-oncology research [14, 15, 30]. The study’s approach was in line with the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist [31]; see Supporting Information 2 for the checklist.

2.2. Participants

We recruited using convenience sampling through networks and contacts, purposive sampling whereby we actively sought people from a variety of backgrounds and disciplines, and snowball sampling where we asked participants who else they would suggest. We recruited participants from all healthcare disciplines, public and private sectors, and they had different levels of experience in the field. Fourteen participants were recruited from a range of organisations and sites. Participants in this study were health professionals in Western Australia (WA) with experience working in oncology. Inclusion criteria were working in an oncology setting, over 18 years of age, and having at least 1 patient who had refused evidence-based treatment. Exclusion criteria were not working in an oncology setting and no experience of patients refusing treatment.

2.3. Data Collection

Semistructured interviews were conducted in late 2021 and 2022 to explore oncology health professionals’ experiences of, and views on, cancer treatment refusal by patients. The interviews were conducted via video conference or telephone (depending on participant preference), or face to face at the participant’s office. Semistructured interviews are useful for exploratory research of this nature, as they can elicit rich information about the desired topic while still providing participants with flexibility to express themselves organically [32]. The semistructured interview questions were developed from discussions with oncology health professionals and team members, and from the literature on the topic (see the Supporting Information 1 for the interview guide). Team members were researchers and clinicians with extensive experience in oncology research, working in oncology settings, with wide-ranging networks of oncology health professionals and clinicians. We included questions on key aspects of participants’ experiences with, and views of, treatment refusal among cancer patients, such as barriers to and facilitators of standard treatment uptake, the types of alternative treatments used by people, and types of communications they had about standard and alternative treatments with cancer patients. Example questions included: Can you tell me about patients who have refused evidence-based treatment? This was followed by a prompt to give examples. Can you tell me what you think motivated people to refuse treatment? What do you consider to be the key reasons for refusing treatment? How many people per year (on average) refuse treatment? What strategies do you use to communicate with people refusing treatment? Are you aware of clinicians with different views to you (in relation to communication and keeping the door open)? Interviewers prompted participants for more information when required and asked for examples, and the semistructured interview schedule was flexible to allow for natural conversational flow. Interviews were digitally recorded for transcription purposes. Data collection ceased when information power was reached (i.e., when sufficient depth and richness were attained) [33]. The quotes were lengthy and included rich, detailed information, relevant to the research aim. This concept suggests that if information relevant to the topic of interest is provided, then fewer participants are needed [33]. We also collected information from a specific and relatively homogenous sample of health professionals, and the study had a narrow focus and aim. The interviews took an average of 85.7 min (standard deviation = 12.82; range = 62–105 min). Similar methods have previously been used to examine cancer care and treatment decisions among patients and health professionals [33, 34].

2.4. Procedure

After receiving human research ethics approval (HRE2021-0127), health professionals, identified via networks, team members and participants, were approached via email and invited to participate. All those contacted indicated an interest, and they were sent a study information sheet and consent form. Subsequently, three people declined to participate due to time restraints. Following the provision of written informed consent, a demographic questionnaire was provided, and an interview was arranged. The interviewers (M.O and T.W) provided a general introduction about the study, and participants had the opportunity to ask questions. Participants were reminded of their right to withdraw at any time.

2.5. Data Analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim and anonymised. The analysis was conducted manually. During the analysis and interpretation, we used a social constructionist lens to explore the meanings the health professionals attributed to patients’ decision-making and to discover possibilities for action and change [35]. Reflexive thematic analysis was used to analyse the data, which involved the researchers extracting meaning and themes from the data [36–38]. The process involved several steps; researchers (T.W., A.P. and M.O.) read the interview transcripts multiple times to familiarise themselves with the data and detailed notes were taken. The codes evolved using reflexive practice. We started with codes that were identified in the data, and we wrote notes and reflected on meanings and concepts that stood out. We then refined these codes into broader categories and reflected on how they related to each other and any underlying meanings we could identify. Finally, we identified overarching themes. M.O. and A.P. reviewed the themes independently, initially, then reviewed together and discussed. Again, we critically reflected on meaning and reached agreement.

2.6. Quality and Rigour

As per Guba and Lincoln [39], we used the concepts of credibility whereby we sought feedback on our findings before our final write-up; dependability and confirmability by ensuring clear documentation such as a transparent audit trail and reflexive notes, detailing the research process, decisions made and why, and contextual factors related to the interviews. We also reached confirmability and transferability by using extensive quotes and examples. Reflexivity was used throughout the analysis and interpretation. The final interpretation process was carried out by a team of researchers to allow for reflexivity and discussion.

3. Results

We recruited 9 males and 5 females with a mean age of 46.57 (SD 7.62). We recruited people working across public and private sectors and from a range of disciplines, backgrounds and roles. Participants had a mean of 14.13 years of oncology practice (SD 9.73). Table 1 provides the sample characteristics.

| Mean (SD) (range)/count | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 46.57 (7.62) (range = 36–62) | — |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 9 | 64.29 |

| Female | 5 | 35.71 |

| Sector | ||

| Public | 4 | 28.57 |

| Private | 4 | 28.57 |

| Both | 6 | 42.86 |

| Role | ||

| Medical oncologist | 4 | 28.57 |

| Radiation oncologist | 1 | 7.14 |

| Surgical oncologist | 2 | 14.29 |

| Cancer nurse | 1 | 7.14 |

| Haematologist | 2 | 14.29 |

| Orthopaedic surgeon | 1 | 7.14 |

| Allied health professional | 3 | 21.43 |

| Employment | ||

| Full-time | 9 | 64.29 |

| Part-time | 4 | 28.57 |

| Casual | 1 | 7.14 |

| Duration in oncology (years) | 14.13 (9.73) (0.88–31) | — |

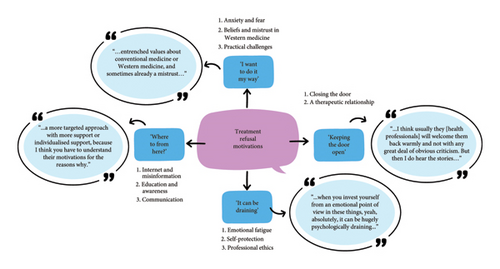

‘I want to do it my way’

The central organising concept of this theme can be summarised as navigating treatment refusal, autonomy, beliefs and mistrust in medical authority. Exploring participants’ experiences of people refusing standard conventional treatments for cancer revealed multiple, complex motives. These factors ranged from cultural beliefs to the fear of toxicity from standard treatments. Moreover, decisions by patients appeared to be influenced by the lived experiences of others’ treatment journeys.

‘…we’ve had a couple of patients [who] refused upfront but accepted later when things got really bad, when there isn’t a curative option, and that’s actually even more morbidity and heartbreak’ (Helen).

3.1. Anxiety and Fear

‘…I think anxiety is more of a prevalent problem. I think there’s a lot of patients who really struggle’ (Margot).

Participants recognised apprehension in people when it came to conventional treatment options, commenting that ‘…most people will have hesitancy from the beginning about accepting conventional medical treatments’ (Alicia). This participant added that such hesitancy appeared to be triggered by perceived severity of conventional treatments, ‘…there are some treatments that seem a lot worse than others’ (Alicia). However, participants stated that the ‘…fear [is] based on the view of cancer treatments that was real 10 years ago, not now’ (Craig). Participants recalled experiences with patients, commenting ‘[They are] saying that the CT scans and the contrast is poison, radiation is going to cause cancer, chemotherapy causes toxicity to the body’. (Ethan)

‘[It is mainly] middle aged men—I think there is a huge gender or societal component, culture, of not wanting to have stomas or bags…it is unfortunately still seen as a disability, just the whole idea that you can’t do anything once you have a bag … There is a huge stigma around it’. (Helen)

‘… if someone has a low rectal cancer and they know that eventually that means that they’ll have a permanent colostomy, sometimes that’s automatic, shutters go up, they’re not willing to accept that. They’ll try everything else first, they’ll try every experimental treatment, they’ll try chemotherapy and radiotherapy but that’s one thing that that’s their deal breaker’. (Margot)

Alongside fear participants also talked about loss of hope and identified that, at certain points, and after certain experiences, people start to question their treatment, for example, ‘It’s normally when I’m not giving them any good options, I’m taking away their hope or their hope is dwindling, [and] side effects of treatment are really starting to affect them’. (Craig)

3.2. Beliefs and Mistrust of Western Medicine

A further contributing factor to treatment refusal was a patient’s cultural beliefs and their thoughts about western medicine. Participants reflected on their experiences, commenting, ‘[decisions about treatment can be] much more cultural or religious… (Alicia)’. In some instances, it was acknowledged that there were ‘…entrenched values about conventional or western medicine and sometimes already a mistrust… (Ethan)’. Further, ‘There are certainly patients who come in with a completely different belief system to western medicine’, further acknowledging that such belief systems ‘[are] a really big challenge (Braden)’ when discussing treatment options with patients. Another participant added that ‘…sometimes what we hear is family members telling them it might not be the right way to go’ (Kristy). One participant summarised the cultural aspect of treatment refusal:

‘I think there’s sort of culture within cultures and the internet in recent years has probably made that even worse. What I see are people who are in kind of echo chambers of people who agree with them who think that chemotherapy particularly is poison and that big pharmaceutical companies are profiteering and don’t have your best interest at heart … they’re really afraid of having their philosophy challenged or having their belief system dismissed … they’re quite anti-authoritarianism; they don’t like experts, they don’t like being told what to do…They see themselves as choosing an alternative lifestyle and part of that alternative mindset is a philosophy that natural is better rand that anything that is made in a laboratory is probably not for them’. (Nora)

‘…it’s often mistrust of western medicine or a fear of complications of therapy or sometimes it borders on conspiracy theories. So it’s a mixture of things but the most frustrating situations are where the patient is just a non-believer or they believe that someone else can offer them a natural alternative or alternative medicine, and often it’s we’re going to offer you a treatment that has toxicities that are potentially significant versus another person who’s saying I can offer you something that’s definitely guaranteed to work and has no side effects. People get sort of stuck down that rabbit hole’. (Jason)

‘Sometimes there is religion that’s involved, and people will tell me “My God will save me, the people in church are praying for me, I believe that this will be cured without the need for any kind of treatment”’. (Ian)

The perception that cancer patients were reflecting on treatment outcomes based on the lived experiences of others was also identified.

‘…or it’s personal experience that their own relatives … or friends who have undergone therapy, usually for a cancer that’s not colorectal, and have had a [bad] outcome.’ (Helen)

A related point was ‘…family history type things or historical things in their own lifetime that they’ve seen…the worst of what can happen when someone goes through treatment for cancer’. (Nora)

Participants acknowledged that seeing the side effects of treatment on others resulted in refusal, commenting that some people say, ‘I don’t want any treatment; my mother or father or family member had a terrible time on chemo and it was just a disaster’ (Craig).

3.3. Practical Challenges

‘…family and transport but the other thing is … becoming homeless, losing all that connection with families and not having a place to stay and they’re going couch surfing or just going to different towns and that sort of messes up the routine for them.’ (Kristy)

‘Keeping the door open’

The central organising concept of this theme is maintaining open communication, balancing professional guidance and patient autonomy in cancer care. Participants highlighted that it was essential to keep lines of communication open between clinicians and the patient, and that, generally, a key focus was to keep the doors open to patients, even those who sought alternative treatments.

3.4. Closing the Door

‘I do hear of that [closing the door] happening still. I mean, it shocks me that it does happen, but it certainly does …’ (Braden)

‘I think there’s still some clinicians out there that have that mentality of this is my knowledge, this is my experience, this is my recommendation. And either take it personally if the patient doesn’t acquiesce or if the patient refuses or questions. … Their body language can change, they might become disinterested in what the patient’s saying or quite dismissive I think is something that I’ve seen, where they can say you can go and do that but you’ll be back in my office in six months’ time begging me for treatment’. (Margot)

‘…lots of them [health professionals] keep the door open and are not so judgmental and, you know, they might feel worried or sad for these patients who go off track for a while but I think usually they will welcome them back warmly and not with any great deal of obvious criticism. But then I do hear the stories … [people] get told that they are stupid and that they’re taking their life in their hands’. (Nora)

3.5. A Therapeutic Relationship

‘I’m not trying to dismiss what they’ve heard or learnt about’ (Ethan), however, ‘…by showing open-mindedness and a respect, you create an open door that the person can come back through.’ (Braden)

‘I have a skillset to help patients with a range of diseases through surgery. I am part of a team and partner with the cancer patient to get the best possible results and not to judge if they make irrational decisions but inform and educate about the consequences of those decisions…I keep the door open’. (Derek)

‘…my approach is not to tell them and bully them into it but you want them to come along on the journey with you so to be very open and honest, give them a chance to think about it, give them more information’. (Craig)

‘It can be draining’

Our central organising concept for this theme is: The emotional and professional burden of cancer treatment refusal, navigating compassion, ethics and systemic pressures. Health professionals mentioned the impact that patients refusing treatment had on them. Challenges included the emotional toll, time taken to work with patients who are refusing or not adhering to standard treatment, professional tensions, ethical considerations and trying to accommodate patients’ wishes.

‘[They are] some of the hardest patients to deal with’ (Jason) and situations where family members ‘collude’ was seen to be frustrating ‘…and you feel like banging your head against a wall….this is your daughter you’re talking about’. (Ian)

Participants also stated that patients were sometimes not open with them, and reflected on how secretive some patients can become about the treatments that they were undertaking, for example ‘…my hunch, but they are [patients] probably not telling us [about] a lot of the stuff that they’re doing…’ (Craig). This had an effect on therapeutic relationships.

3.6. Emotional Fatigue

‘Well, I mean, there is a little bit of—not necessarily compassion fatigue, but there is a little bit of fatigue, so I think it goes unrecognised, the level at which some clinicians do adapt their practice to understanding where they’re coming from’. (Helen)

‘…some of the things we deal with are emotionally confronting and when you invest yourself from an emotional point of view in these things it can be psychologically draining and then compassionate, emotional barriers are put up to protect yourself against some of these things’. (Helen)

Participants said: ‘the first few times it happens to you it is really distressing’. (Ian) But went on to say they had learned to say ‘OK, this is not a situation I’m going to win’. (Ian)

Time pressure was mentioned as an issue where the, ‘…first appointment is 40 min—diagnosis, treatment, side effects, impact on family, psychological health, everything and then having to discuss why the treatments offered are a better option than alternative therapies can add to that “time pressure”’. (Craig)

3.7. Self-Protection

‘Certainly, in the public system … if [the patient is] feeling uncomfortable with a situation, they may ask another oncologist to be involved as a second opinion—we do that quite commonly at [our] hospital and I think (1) to protect the patient and (2) to protect staff, particularly in difficult situations’. (Craig)

These protections also included taking ‘…detailed notes in case of litigation’. (Ian)

3.7.1. Professional Ethics

‘If we’ve got someone who we’ve said go away, think about it, come back again and we’ve seen them for five visits and spending 45 min with them every time, it’s a pretty big use of financial and other resources. I don’t know what the solution to that is’. (Ian).

‘Where to from here’

We identified the following central organising theme: Enhancing patient education and communication, addressing misinformation and strengthening engagement in cancer care. Examining health professionals’ experiences of, and views about, treatment adherence and refusal highlighted potential ways forward. These ways included increasing education for patients on how to locate, interpret and understand scientific data relating to treatment, education for health professionals on effective communication approaches, helping patients identify legitimate information, and the need to produce targeted campaigns to address misinformation.

3.7.2. Use of the Internet and Misinformation

‘…the modern access to digital information is really destructive … you can find anything you want on the internet to support your point of view and that’s a problem’. (Craig)

‘…the vastness of information that’s out there now, it’s hard to wade through and know what’s reliable and what’s not’. (Felix)

‘…a lot of it seems to be driven by stories and testimonials more than evidence and they convince people’. (Margot)

3.8. Increasing Education and Awareness

Participants discussed the effectiveness of increasing patient education and awareness. It was suggested that a targeted approach to patients should be considered, for example ‘I think in those patients, a more targeted approach with more individualised support, because I think you have to [take into account] their motivations for the reasons why [they refuse treatment] …’ (Ethan)

3.9. Communication

There was acknowledgement that treatment discussions are difficult and there is not one approach that fits all, for example, ‘… I will say there’s no one rule fits all in these situations. I mean, I think you have to gauge during the conversation how things are going’ (Ethan). However, when reflecting on the ability of health professionals to engage and have treatment discussions with patients, participants commented on the lack of training received, for example, ‘We need to have more effective communication training. … it was also identified that changing some health professionals’ approaches may be difficult, “…we won’t be able to change because they [doctors]—as you say, they’re busy, they’ve got other things and for them they’re just not going to [add anything]”’ (Alicia). To mitigate this challenge, it was suggested training a specialist team from the beginning to help manage patients questioning their treatment plans, for example, ‘…maybe educating others would be useful and maybe ensuring that there is a core of doctors who are better at managing these patients’. (Alicia)

‘I try to share balanced information, evidence-informed information to some of those groups and audiences [people using the internet or social media]…So I think education broadly but using the same tools that the charlatans use, that’s one way…there’s a game that’s being played and it’s all to do with the algorithms of all of their social media channels, you have to post regularly and at the right times and so no legitimate health organisation does that. The charities can’t do it, medical research institutes can’t do it…that’s what needs to be done. You need to meet the audience where they are and use some of the same hooks that get them in…So journal articles don’t get read but summarising systematic reviews and turning them into reels [which] are the latest thing on Instagram that get a lot of eyes on them; it’s like a quick slideshow of four or five tiles that just say did you ever wonder about this? Systematic review, 19 studies, 20,000 people, this was the results, find out more here. And then you link to the actual article’ (Margot)

4. Discussion

We identified four themes: ‘They want to do it their way’; ‘Keeping the door open’; ‘It can be draining’; and ‘Where to from here?’. All themes included detailed and nuanced examples and reflections. While a small proportion of people refuse treatment, which was borne out by our participants’ experiences, we found that treatment refusal had a disproportionate impact on individuals, families, health professionals and the health system, including time spent engaging with patients contemplating refusing treatment.

Our findings revealed complex and multifaceted motivations for treatment refusal. Treatment refusal is often based on balancing the positives and negatives of standard treatments; however, our findings suggest that health professionals consider the main motivations to be psychological in nature. These findings are in line with Khankeh et al. [8] grounded theory research with people diagnosed with cancer, carers and health professionals, Moodley et al. [40] systematic review of treatment refusal in colorectal cancer patients, and a 2015 systematic review of older people’s reasons for refusing cancer treatment [11], In Khankeh et al. [8] qualitative study, the health professionals interviewed highlighted that patients’ and families’ ‘reserves’ often run out resulting in a depletion of psychological and emotional resilience and, consequently, treatment refusal.

We found that fear of the implications of treatment generally played a major role in our study; with examples including treatment toxicity, and the potential need for a stoma in people with colorectal cancer. The fear spoken about was often exacerbated by recalling the negative experiences of relatives or friends with cancer. These findings echo Dias et al. [19] systematic review, where studies suggested that psychological aspects of care and treatment such as dealing with fear of adverse events need exploration and greater discussion. A systematic review of 38 studies relating to older adults’ treatment acceptance or refusal, also found that a key reasoning for treatment refusal was fear, particularly of side effects [18]. Fear is common among cancer survivors [41–43], and appears to be an important domain of consideration relating to cancer treatment refusal.

Overall, our findings emphasised that the beliefs and world views are significant in decisions to refuse conventional treatment. Similarly, Radley and Payne [21] reported that refusal can be driven by people’s views on conventional medicine. It is clear that some belief systems and world views, including a distrust of pharmacology and conventional western medicine generally, are major factors in resistance to conventional treatments [44, 45]. Verhoef et al. [28] reported that, in their study, a belief in holistic healing appeared to have promoted or encouraged treatment refusal. A qualitative study by Citrin et al. [46] also found many patients refused chemotherapy and radiotherapy due to their perception of such treatments as high risk. Participants in their study characterised chemotherapy as poison and placed greater trust in alternative therapies. Internet searches, profiling testimonials of the success of alternative cancer therapies strengthened participants’ beliefs.

A qualitative study of oncology medical professionals’ and patients’ perspectives on the use of complementary and alternative therapies (CAM) found that views between the 2 groups were, at times, very different and this could lead to tension and conflict as both groups’ points of view became more extreme [47]. Medical professionals emphasised medical reasoning and patients focused on their values. The authors suggested further education on CAM for oncology medical professionals; however, their findings indicated that many medical professionals do not consider this to be necessary. The authors concluded that shared decision-making can be challenging, but clear and respectful communication is vital.

The health professionals in our study spent a great deal of time talking to patients to explain their treatment options, and to accommodate the patient’s wishes. The discussions were described as intense and led to feelings of being ethically compromised as the time could have been available to other patients. They also resulted in a cost to an overstretched health system. The health professionals described the importance of acknowledging the values and beliefs of patients and respecting their autonomy in decision-making. Again, considerable time is required to achieve this, to establish and maintain rapport, develop respect, and to allay any fears or misconceptions. This contradicts findings that a poor relationship with health professionals contributes to treatment refusal by patients [20] but reflects findings reported in van Kleffens et al. [48] qualitative study from the Netherlands, where medical professionals stated that patients need sufficient medical information to have autonomy in decision-making and that medical professionals played a major role in communicating that information.

Such discussions and resulting tensions when balancing the needs of all patients and the health system took an emotional toll on health professionals in our study and were difficult and distressing. Turner and Kelly [49] reported that caring for people with chronic medical conditions, generally, resulted in strong emotional reactions among clinicians such as anxiety, which can lead to distress and emotional burden as the clinicians are exposed to patients’ and families’ ongoing suffering. These authors stated that these feelings may be balanced by a sense of accomplishment from providing consistent care. However, this balance is not necessarily achieved if patients refuse conventional treatment as clinicians may have feelings of failure, helplessness or concern [28]. It is important to acknowledge the emotional impact of treatment refusal and of the consequences of intense discussions to try and maintain treatment adherence for oncology health professionals, especially as research indicates that oncology health professionals experience greater levels of burnout than other health professionals [50]. A related area is the stressors related to the pandemic and caring for COVID-19 patients, and people who were antivaccination, led to an inordinate amount of time discussing the issues for intensivists [51, 52]. These stressors often resulted in compassion fatigue. Magnavita et al. [52] suggest the need for training and structural polices to support health professionals. Generally, interventions and supports are needed to prevent or reduce compassion fatigue and burnout. An evaluation of a 6 -week mindfulness-based compassion training intervention for health professionals involved in end-of-life care found the intervention reduced levels of anxiety, compassion fatigue (burnout), and emotional exhaustion and increased levels of compassion satisfaction and self-compassion [53].

One ethical and professional response to cancer treatment refusal was for health professionals to ‘keep the door open’. All participants in our study stated that they try to keep lines of communication open and to maintain trust by remaining open to patients returning to the system after an earlier period of treatment refusal. These findings reflect those reported by Verhoef and White [54] who acknowledged the importance of respecting patients’ views, listening and keeping the door open for patients to return to the system as they require further health care later in their cancer trajectory.

Participants in our study also believed the quantity of information available to patients via the internet is making it difficult for people to isolate reliable information. They articulated the way forward is not necessarily public health campaigns, but rather information targeted at individual patients. This supports our comments on the complexity of motivations for refusing treatment. Findings also acknowledged that oncology health professionals need to meet patients ‘where they are at’ and use social media, and other forms of education, to present evidence-based information in an up-to-date, social media friendly way. We believe this is a novel finding and one that warrants further attention and resources. Certainly, the internet promotes misinformation and often harmful information [26]. A suggestion by Puts et al. [11] is that a validated tool be developed to capture reasons for refusal. They also suggest that cognition is assessed, which is interesting in the light of recent cancer-related cognitive impairment (CRCI) research findings, which suggest that CRCI affects many aspects of people’s lives including decision-making [14, 15, 55, 56]. Puts et al. [11] also emphasise that supports and interventions are tailored to populations, particularly as people age.

We did not find that financial reasons were a motivation for treatment refusal as per a study conducted in China [7]. This may be due to people preferring not to disclose this to health professionals or that WA has a different medical system to China.

4.1. Limitations

Our interviews captured rich and layered information about treatment refusal from a range of oncology health professionals. However, we identified limitations. We acknowledge that we did not recruit participants who were not open to patients returning to the system and our participants may have self-selected into our study. We also note that we did not obtain data regarding how many patients refused evidence-based treatments. Further, given that the participants were recruited from one Australian state, we should be cautious when considering other locations.

5. Conclusions

Treatment refusal is complex and, as such, responses need to reflect this complexity and individual variability. Participants in our study articulated the need to keep the door open to patients who previously refused conventional evidence-based treatment but also highlighted that supporting these patients was draining for them. Statistics and research need to be presented in different ways, including via social media, for them to be palatable to people who are contemplating refusing conventional, evidence-based treatments. This approach would reflect what patients appear to value in alternative therapy sites. It would be particularly useful to have people who initially refused treatment or sought alternative treatments to tell their stories. Supports for oncology health professionals are needed to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout.

Disclosure

This research was presented at the MASCC/JASCC/ISOO Annual Meeting 2023 and the abstract from this presentation was published in Supportive Care in Cancer.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: M.O., T.W. and A.P. and D.H.; methodology: M.O., A.P. and T.W.; formal analysis: M.O., A.P. and T.W.; investigation: M.O., T.W., A.P. and D.H.; resources: M.O. and T.W.; data curation: M.O. and T.W.; writing – original draft preparation: M.O., T.W., A.P. and D.H.; writing – review and editing: M.O., T.W., A.P., J.J., N.H.H. M.T. and D.H.; supervision: M.O.; project administration: M.O. and T.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. N.H.H. and D.H. are joint senior authors.

Funding

Nicolas H. Hart was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council, APP2018070. This research received funding from the WA Clinical Oncology Group (WACOG), Cancer Council WA.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank and acknowledge all participants who generously gave their time to be interviewed. We would like to thank Professor Christobel Saunders who assisted in the initiation of the concept. We would also like to thank and acknowledge WACOG, Cancer Council WA, for their support.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Anonymised data may be made available from reasonable request from the corresponding author and to the satisfaction of the granting ethics committee.