Examining Recruitment and Retention Strategies in Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Trials: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

Background: To ensure equitable and successful treatment outcomes for hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), the recruitment and retention of diverse participants in clinical trials is critical. However, current approaches may neglect under-represented populations, potentially limiting the result application.

Objective: This study aimed to evaluate existing recruitment and retention strategies in HS trials, identifying gaps and proposing methods to improve inclusivity and participant retention.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 36 HS clinical trials from January 2018 to December 2023, following PRISMA guidelines. Trial characteristics and specific recruitment/retention approaches were assessed through data extraction and Stata 18 SE statistical analysis.

Results: Of the 36 trials, 18/36 (50.0%) reported use of specific retention strategies, while 1/36 (2.8%) of the trials documented recruitment strategies for under-represented groups. Diversity goals were also unreported in recruitment processes. Most trials (63.9%) received industry funding, and therapeutic intervention was the most common treatment type (97.2%).

Limitations: Only articles from 2018 to 2023 were analyzed, limiting the finding generalizability over broader timeframes.

Conclusion: This study reveals significant gaps in recruitment/retention strategies within HS trials, which is important for enhancing result relevance and inclusivity, particularly among historically marginalized populations. Implementing specific approaches and innovative methods is critical for improving HS treatment efficacy and reducing health inequities.

1. Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), also known as acne inversa, is a chronic inflammatory dermatologic condition characterized by recurrent painful nodules, sterile abscesses, and sinus tracts. Intertriginous areas, such as the axillae and groin, are primarily affected, but depending on severity, other areas can be implicated in the disease. The current literature elucidates HS to be an inflammatory disorder originating from the hair follicle with follicular rupture releasing bacterial and keratin debris resulting in relapsing and remitting cutaneous inflammation [1].

Despite its clinical significance, HS remains an under-recognized disease with an average diagnostic delay of 7–10 years, greatly impairing the patient’s quality of life and poor outcomes from disease-specific sequalae [2]. Notably, the disease is more prevalent among women and African Americans, with some cases being inherited in an autosomal dominant manner from mutations in the γ-secretase complex [1, 3, 4]. The prevalence of HS varies widely across different populations and regions, with estimates ranging from 0.05% to 4% of the general population [5]. On average, Black Americans consult with a dermatologist around 5 years after the onset of HS, which is approximately 2 years later than their White and Hispanic American counterparts [6]. These factors can lead to the worsening of symptoms and increased complications. This delay, along with the challenges in diagnosis, treatment, and management of HS, contributes to substantial physical and psychosocial burdens for those affected. A recent meta-analysis finding revealed the prevalence of comorbid depression (26.5% vs. 6.6%) and anxiety (18.1% vs. 7.1%) in those with HS versus control [7]. Additionally, those with HS are found to have higher rates of substance abuse, psychotic and bipolar disorders, and an increased suicide risk compared to the general population [8].

Inequities in the prevalence and management of HS exist among inequitable populations, including racial and ethnic minorities, persons with low socioeconomic status, and those with limited access to healthcare resources. Research indicates that these populations are disproportionately affected by HS, experiencing higher disease burden, delayed diagnosis, and poorer treatment outcomes compared to their counterparts [9]. Factors such as genetic predisposition, environmental exposures, and healthcare access contribute to these inequities, exacerbating the physical and emotional toll of HS on marginalized communities.

Our cross-sectional study intends to examine the recruitment and retention strategies employed in clinical trials in HS research. By synthesizing the existing literature and analyzing current practices, we seek to identify potential inefficiencies and barriers that hinder the inclusion of diverse participants. Understanding these challenges is crucial for improving the validity and relevance of research findings, as well as for informing the development of more inclusive and effective recruitment and retention strategies. Ultimately, our study aims to advance equitable and accessible interventions for HS, addressing the pressing need to reduce inequities in dermatological health outcomes and improve the quality of care for all individuals affected by this debilitating condition.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional analysis was conducted to investigate strategies employed in recruiting and retaining participants in clinical trials concerning HS. This study followed guidelines from the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [10, 11]. Since this study used systematic review methods, we did not adhere to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guideline (STROBE), as PRISMA guidelines were more applicable. Our protocol was submitted to the Institutional Review Board (IRB), which concluded that the study did not involve human subject research according to the United States Code of Federal Regulations [12]. Our study protocol, search strategy, pilot-tested Google forms, supplemental data, included and excluded study details, and statistical analyses were submitted a priori to the Open Science Framework (OSF) for reproducibility and transparency [13]. This study was completed alongside other studies that used similar methodologies in other areas of medicine [14]. (Supporting File 1)

2.2. Use of Language

A standardized guide for language, Advancing Health Equity: A Guide to Language, Narrative, and Concepts, by the American Medical Association (AMA) was used throughout our manuscript [15].

2.3. Search String

We searched for interventions regarding Cochrane systematic reviews on HS in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The returns were screened to identify relevant search terms to use when generating our search string for each database. In developing our search string, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms (i.e., “HS”[MeSH Terms]) were employed. On May 28, 2024, we systematically searched medical literature databases including Embase (Elsevier), MEDLINE (PubMed), and Clinicaltrials.gov for clinical trials regarding HS treatments. The search returns were uploaded to a systematic review platform, Rayyan (https://rayyan.qcri.org/). Two authors (Jeanie Marchbanks and Eddy Bagaruka) screened the results in a masked, duplicate fashion, adhering to guidelines from the Cochrane Collaboration to avoid bias and enhance the reliability of our findings [16].

2.4. Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria for our cross-sectional analysis of clinical trials were as follows: (1) included trial participants with HS, (2) assessing the efficacy of an intervention (pharmaceutical, behavior, supplemental/holistic, or other management), (3) published between January 1, 2018 and December 31, 2023, and (4) trials conducted in the United States or countries with a national or multinational ethnic fractionalization index (EFI) of ≥ 0.3. The EFI measures ethnic diversity within a population and gives the probability that two individuals selected at random from a given region or country belong to different ethnic groups [17]. An EFI value closer to one indicates a more diverse population, while a value closer to 0 indicates a more homogenous population. This is frequently used as a method of assessing the diversity of a country and is the potential for diversity within clinical trial populations.

We excluded (1) interim analyses, (2) secondary analyses, (3) trial updates, (4) erratum, (5) corrigendum, (6) non-English studies, and (7) animal studies. The two authors (Jeanie Marchbanks and Eddy Bagaruka) screened the studies based on the inclusion criteria and reconciled any discrepancies. If there were any disagreements, a third author (Merhawit Ghebrehiwet) was consulted to resolve the issue.

2.5. Data Extraction: General Characteristics

In a masked, duplicate fashion, two authors (Jeanie Marchbanks and Eddy Bagaruka) extracted data using a standardized Google form to gather the following information from each eligible trial: publication year, source of funding, first author names, corresponding author and contact information, the total number of authors including each author’s first name, interventions and their classification (therapeutic, behavioral, supplement/holistic, and other), duration of the study, location site (country), target efficacy outcome, masking type and randomization (single, double, or greater than double-blind), study population (target population by disease, comorbidities, or specific subgroups), excluded comorbidities, and age (range and mean).

2.6. Data Extraction: Specific Characteristics

In addition, data were extracted regarding recruitment and retention strategies and recorded. Specifically, a trial would be credited for having a recruitment strategy if it included efforts to recruit under-represented groups, employed community engagement practices, or used strategies such as culturally tailored materials, local recruitment sites, or incentives to encourage diverse participation. The intention-to-treat sample size, withdrawals, and loss to follow-up were also recorded. Retention-related variables include comparison of the planned diversity goals with the recruited population, measures put in place to reduce dropouts, and ethical considerations regarding the recruitment of diverse populations. Any challenges and limitations experienced by the authors about diverse recruitment were documented.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Gender-API.com, an artificial intelligence program with a Google Sheets extension, was used to predict the author’s gender. Gender-API compiles global data to determine the likelihood that an individual’s first name is a specific gender. It is known to be one of the most precise gender-detection tools in meta-analysis research [18]. General study characteristics and the use of recruitment and retention strategies were presented as percentages and frequencies. All data analyses were performed using Stata 18 SE (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

For trials located at multinational sites, the unweighted and weighted mean EFIs were calculated. If trials documented country-specific sample sizes, the weighted mean was calculated; otherwise, the unweighted mean was calculated. The unweighted mean EFI was calculated by taking the average of each country’s EFI. The weighted mean EFI was calculated by multiplying the total number of participants per country by the country’s EFI, summing these products, and dividing by the total number of participants in the trial [17].

3. Results

3.1. Trial Inclusion and Exclusion

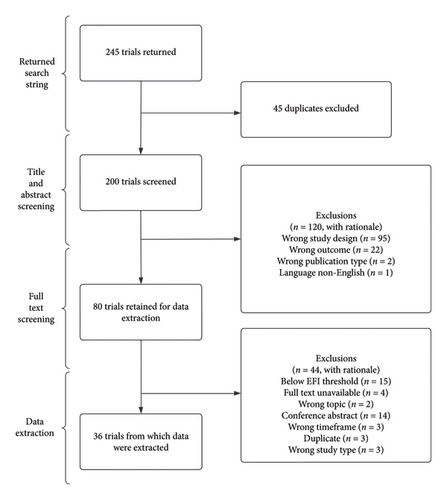

The database search yielded 245 records. Duplicates were removed, resulting in 200 records. The remaining records were screened, and 80 articles were retained after full-text screening. Thirty-six studies met the inclusion criteria for data extraction (Figure 1 and Supporting File 2).

3.2. Trial Characteristics

A total of 10 studies were performed in 2023 (10/36, 27.8%). Seventeen studies were conducted in multisite locations across the U.S. and other foreign countries (17/36, 47.2%), with a lesser amount not reporting the location of their study (2/36, 5.6%). Most trials received industry funding (23/36, 63.9%), and therapeutic intervention was the most commonly reported intervention type (35/36, 97.2%) (Table 1).

| General characteristics | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Time at which the study was conducted | |

| 2018 | 2 (5.6) |

| 2019 | 3 (8.3) |

| 2020 | 9 (25.0) |

| 2021 | 5 (13.9) |

| 2022 | 7 (19.4) |

| 2023 | 10 (27.8) |

| Location | |

| United States of America (USA) | 10 (27.8) |

| International, including USA | 17 (47.2) |

| International, excluding USA | 7 (19.4) |

| Unable to determine location | 2 (5.6) |

| Randomization | |

| Yes | 26 (72.2) |

| No | 10 (27.8) |

| Masking | |

| Single | 2 (5.6) |

| Double | 16 (44.4) |

| Greater than double | 7 (19.4) |

| None | 11 (30.6) |

| Funding | |

| Private | 1 (2.8) |

| Industry | 23 (63.9) |

| Self-funded | 0 (0.0) |

| Hospital/university | 8 (22.2) |

| Government | 1 (2.8) |

| No funding | 2 (5.6) |

| Not mentioned | 1 (2.8) |

| Mixed | 0 (0.0) |

| Classification of intervention | |

| Therapeutic | 35 (97.2) |

| Behavioral | 1 (2.8) |

| Supplemental/holistic | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) |

| Trials with more than 50% female authors | 5 (13.9) |

3.3. Recruitment Strategies

Of the 36 studies reviewed, 1/36 (2.8%) implemented recruitment strategies, utilizing remote methods due to the COVID-19 lockdown. Additionally, none of the studies mentioned planned diversity goals or any limitations or challenges throughout the recruitment process (Table 2).

| Item assessed | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| 1. Did the study mention recruitment strategies? | 1 (2.8) | 35 (97.2) |

| 2. Was a planned diversity goal mentioned in the methods? | 0 (0.0) | 36 (100.0) |

| 3. Were any considerations/ethical approvals taken concerning diversity recruitment? | 0 (0.0) | 36 (100.0) |

| 4. Are any limitations/challenges to recruitment mentioned? | 0 (0.0) | 36 (100.0) |

| 5. Were any measures taken to prevent participant dropout? | 18 (50.0) | 18 (50.0) |

3.4. Retention Strategies

Of the 36 studies, 18/36 (50.0%) studies took measures to minimize participant dropout rates. Retention strategies included but were not limited to the following: follow-up phone calls, texts, certified letters, and offers for transportation support to encourage participation and address potential barriers (Table 2).

4. Discussion

Our study reveals a significant gap in the recruitment and retention strategies within HS clinical trials. Despite the prevalence of HS in under-represented populations, recruitment and retention strategies for these populations were limited in quantity. Additionally, none of the studies mentioned diversity goals in the recruitment process. These findings highlight a critical deficiency that may undermine the generalizability and relevance of HS trial outcomes, particularly in relation to diverse and marginalized populations. The unreported presence of these strategies suggests that current HS research may not adequately address the needs and experiences of all affected groups, potentially limiting the efficacy and applicability of new treatments and interventions developed through these trials.

Our analysis of HS clinical trials reveals a significant gap in the diversity of participant demographics, which limits the ability to generalize study findings to the broader HS population. While White participants comprised the majority in most trials, Black individuals, who are disproportionately affected by HS according to Bukvić Mokos et al., were under-represented in several trials despite their higher disease burden [19]. Similarly, Hispanic, Asian, Native American/Alaskan Native, and Pacific Islander/Hawaiian populations were either minimally included or not reported, making it difficult to assess whether their recruitment reflects their true HS burden. Sex was reported in 35 trials, with female participants being the majority, reflecting the higher prevalence of HS in women. These findings highlight the need for more inclusive recruitment strategies in HS research. Future trials should prioritize diverse enrollment, standardize race and ethnicity reporting, and address potential barriers to participation to ensure that findings accurately reflect the broader HS patient population (Supporting File 3).

Our findings align with the existing literature that underlines persistent challenges in recruiting and retaining under-represented populations in clinical trials, particularly among racial and ethnic minorities, individuals with lower socioeconomic status, and those with limited access to healthcare [20, 21]. For instance, Huang et al. emphasized the ongoing difficulties in recruitment and retention efforts for these populations [22]. HS interventions may vary in their effects across different racial groups, further complicating the landscape of clinical research. Dawson et al. proposed key recommendations for inclusive trial design, such as ensuring eligibility criteria and recruitment pathways that do not inadvertently limit participation, developing culturally sensitive trial materials, and fostering partnerships with community organizations [23]. These recommendations are critical for creating a more inclusive research environment that adequately represents the diversity of the patient population affected by HS.

The unreported presence of thorough recruitment and retention strategies in HS trials exacerbates existing health inequities, limiting the applicability of research findings to real-world, diverse populations. This lack of inclusivity in clinical research perpetuates health inequities and hinders the development of equitable healthcare interventions. Without addressing these inequities, the medical community risks developing treatments that are less effective or even harmful to under-represented groups, thereby widening the gap in healthcare outcomes. Therefore, it is imperative to implement strategies that ensure diverse representation in HS clinical trials.

To address these deficiencies, specific recruitment and retention strategies must be implemented. Recent recommendations call for legislative updates to support the inclusion of diverse populations in clinical research [24]. The application of strategies to increase accessibility to clinical trials has been found to support participation of more diverse populations [25]. This might be performed through providing incentives, such as financial stipends and gift cards, which has shown positive outcomes in increasing the representation of diverse populations [26]. Locating study sites within under-represented communities can also enhance accessibility and participation [27, 28]. By situating research centers in areas where under-represented populations live and work, researchers can reduce the logistical barriers to participation. Additionally, employing a field-based approach for recruiting Black Americans, as highlighted in studies on cultural humility, can build trust and improve participation. This approach involves engaging directly with the community, explaining the study’s objectives, and emphasizing the importance of participation in a culturally sensitive manner. Advertising in local newspapers and employing snowball sampling methods have also proven to be successful [29]. For retaining under-represented participants, strategies such as reminder telephone calls and addressing participants’ concerns about the study have been reported to increase trust and retention [29].

Future research should focus on developing and evaluating innovative recruitment and retention strategies tailored specifically for HS trials. This approach would provide researchers with valuable insights into increasing participation and preventing attrition among historically marginalized groups, thereby allowing for more representative outcomes in HS research. Additionally, ethnographic or phenomenological research exploring the experiences and perspectives of participants from diverse backgrounds can identify specific obstacles and facilitators to trial participation. Once effective strategies have been identified and implemented, establishing a centralized resource for these successful strategies and practices will be crucial. This resource would facilitate the widespread sharing of knowledge and foster the adoption of proven strategies in HS research. Furthermore, prioritized outreach to minority communities, culturally competent communication, and community engagement are essential components in overcoming barriers to participation. Providing logistical support, such as transportation and flexible scheduling, can also mitigate challenges faced by participants. Ensuring that recruitment materials are accessible and understandable to individuals with varying levels of health literacy is another critical aspect. Comprehensive strategies that address the unique needs of marginalized populations are necessary to achieve these goals and advance the field of dermatology.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

Our cross-sectional study had several strengths, including the use of masked duplicate data extraction to minimize bias and adherence to standardized language guidelines for discussing HS. These methodological approaches ensured that our findings are reliable. However, our study also had limitations, such as being restricted to articles published between 2018 and 2023, which may limit the generalizability of our findings across broader timeframes. Furthermore, our findings were constrained by the decision to include only published HS clinical trials. Although we conducted an additional search on clinicaltrials.gov, we found that none of the unpublished clinical trials provided the necessary information on recruitment or retention strategies for historically marginalized populations. This represents an area that warrants further investigation in future studies. Additionally, excluding non-English studies could have introduced language bias and restricted our sample size. Future research should aim to include studies from a wider range of time periods and languages to provide a more comprehensive understanding of recruitment and retention strategies in HS trials.

Another limitation of our study was that we used the trial registrations on ClinicalTrials.gov and the corresponding publications to locate information about recruitment and retention strategies. This information may have been written about elsewhere, such as in detailed study protocols or materials submitted to institutional review boards. Our search for study protocols yielded one protocol that mentioned recruitment and retention strategies, noting that the COVID-19 lockdown in the UK led to the adoption of remote methods. It is possible that trialists carried out methods to recruit or retain participants that are not described in the trial registrations or publications. We argue that better reporting is needed in trial publications. The CONSORT Equity extension proposes that authors should “Report whether methods of recruitment were designed to reach populations across relevant PROGRESS-Plus characteristics” [30]. Doing so would improve the reader’s ability to fully understand the extent and nature of recruitment and retention practices.

5. Conclusion

Our study emphasizes the urgent need for more inclusive recruitment and retention strategies in HS clinical trials. Addressing these gaps is essential for ensuring the external validity of research findings and for developing effective, equitable interventions for all populations affected by HS. By prioritizing diversity and inclusivity, researchers and healthcare providers can contribute to reducing health inequities and improving outcomes for historically marginalized communities. The promotion of innovative methods and adhering to inclusive, education-based medicine could contribute to improved representation in clinical trials. Additionally, implementing culturally sensitive programs tailored to diverse populations is essential. The development of standardized guidelines for diverse recruitment and retention practices in HS research is imperative to achieve these goals. Future research is necessary to understand the barriers to participation and attitudes toward clinical trials within these communities to enhance the effectiveness of efforts.

Ethics Statement

Our protocol was submitted to the Institutional Review Board (IRB), which concluded that the study did not involve human subject research according to the United States Code of Federal Regulations.

Disclosure

This work was previously presented in an abstract form at the 2024 Symposium on Tribal and Rural Innovations in Disparities and Equity for Health and is available at the following link: <https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation%26hl=en%26user=Qm92tAQAAAAJ%26citation_for_view=Qm92tAQAAAAJ:8k81kl-MbHgC>.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Matt Vassar reports the receipt of funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the US Office of Research Integrity, Oklahoma Center for Advancement of Science and Technology, and internal grants from Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences—all outside of the present work. Dr. Alicia Ito Ford reports the receipt of funding from the Center for Integrative Research on Childhood Adversity, the Oklahoma Shared Clinical and Translational Resources, and internal grants from Oklahoma State University and Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences—all outside of the present work. The authors had no impact on the results or outcomes of the study if this is accurate. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Jeanie Marchbanks: drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data.

Eddy Bagaruka: major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data.

Merhawit Ghebrehiwet: drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data.

Andrew Wilson: drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data.

Payton Clark: drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data.

Josh Autaubo: drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data.

Chase Pitchford: drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data.

Alicia Ito Ford: drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data.

Matt Vassar: drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data.

Funding

This study received no funding.

Acknowledgments

No AI software was used to prepare the manuscript.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on the Open Science Framework (OSF) and are accessible for reproducibility and transparency. All data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.