Intravenous Misplacement of the Nephrostomy Catheter Into the Renal Vein Following Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy (PCNL): A Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

Background: After percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL), intravenous misplacement of a nephrostomy tube is a very rare clinical occurrence. This report summarizes the characteristics and management of intravenous misplacement of a nephrostomy tube.

Case Presentation: We present a rare case of intravenous nephrostomy catheter misplacement after PCNL in a 63 years old male. The tip of the tube was located in the left renal vein. The patient was managed conservatively and treated safely.

Conclusion: Intravenous nephrostomy tube misplacement is a rare PCNL complication. Good Imaging can rule out through and through renal vein perforation and thus patients can be safely managed using conservative approach.

1. Introduction

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) was first introduced by Fernstrom and Johansson in 1976 [1]. It has become as a method to temporarily alleviate the obstruction, infection, and dilation of the kidney and is also the treatment of choice for renal calculi [2]. There are two mandatory steps of PCNL, i.e., puncturing and dilation. Rarely, during dilatation, dilators can cause direct injury to the main renal vein or its tributaries [3]. A nephrostomy tube is routinely placed after PCNL in the renal pelvis in order to control bleeding and drain the collecting system. Although it is a well-established procedure but complication rates of up to 7% have been reported [4]. Intraoperative complications include bleeding, damage to visceral organs, injury to the renal collecting system, pulmonary complications, extra-renal migration of stone fragments, thromboembolic disorders, and incorrect placement of the nephrostomy tube. On the other hand, postoperative complications include infection, persistent urinary fistula, sepsis, bleeding, infundibular stenosis, and, in severe cases, nephrectomy and patient mortality [4]. Therefore, the mechanism and cause of injury should be investigated properly. We report a case of misplacement of nephrostomy tube, who underwent PCNL.

2. Case Presentation

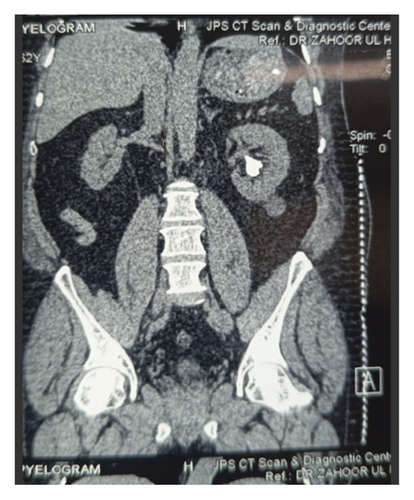

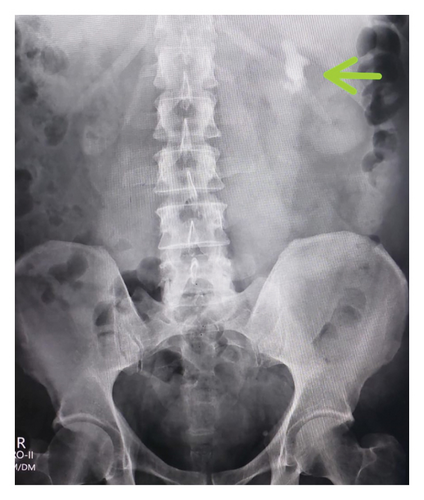

A 63-year-old male with no known comorbidities presented with a six-month history of left flank pain and lower urinary tract symptoms. Radiological investigations revealed renal calculi in the left kidney as shown in Figures 1, 2 and 3 indicating a need for PCNL. The procedure was performed, and a DJ stent was placed for postoperative drainage as shown in Figure 4. Additionally, a nephrostomy tube was inserted for drainage purposes.

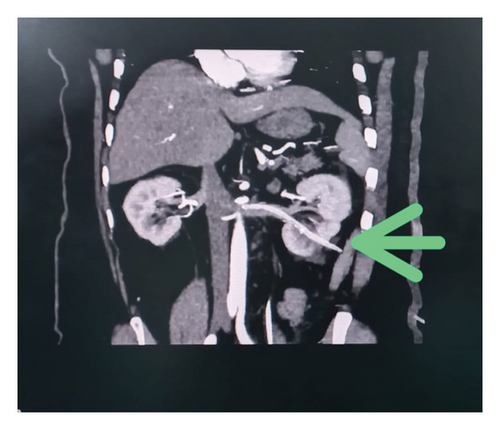

The patient experienced intense bleeding after 5 h following the nephrostomy tube insertion, which subsequently resulted in hypotension later on. He was transferred to the High Dependency Unit (HDU), for resuscitation. Four units of blood along with fresh frozen plasma (FFP) were transfused, stabilizing the patient’s hemodynamics. On further radiological imaging, specifically a CT angiogram, showed that the nephrostomy tube had accidently traversed the lower pole calyces of the left kidney, reaching the left renal vein, with its tip positioned only 2 mm away from the inferior vena cava (IVC) ostium (Figure 5). Patient was kept stabilized through fluid resuscitation and by keeping the PCN tube clamped.

The patient was taken back to the operating theatre to address the cause of bleeding on the second postoperative day. The nephrostomy tube was withdrawn from the renal vein under fluoroscopic guidance, and the plan was to keep it in the kidney pelvicalyceal system. However, due to a nonhydronephrotic system, it came out completely from the kidney, so it was kept as a drain for 24 h. The patient remained vitally stable afterward, and minimal hematuria was observed in the Foley’s catheter, which resolved with hydration alone. Serial ultrasounds were performed at intervals of 6 h, all of which were unremarkable. Subsequent monitoring showed stable hemodynamics as shown in Tables 1 and 2, and no further bleeding episodes occurred.

| Tests | Normal ranges | Unit | Immediately after surgery | 8 h postsurgery | 16 h postsurgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HGB | 13–16.5 | g/dL | 9.4 | 7.6 | 8.6 |

| HCT | 40–52 | % | 28.7 | 23.4 | 35.8 |

| RBC | 4.5–6.5 | 1012L | 3.14 | 2.57 | 2.97 |

| PLATELETS | 150–400 | 109/L | 187 | 183 | 147 |

| WBC | 4.0–11.0 | 109/L | 11.56 | 12.88 | 15.99 |

| Tests | Results units (on the day of procedure) (mg/dL) | Results units (4 days after the procedure) (mg/dL) | Reference range (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urea serum | 25 | 23 | 15–39 |

| Creatinine Serum | 0.9 | 0.83 | 0.5–1.5 |

3. Discussion

PCNL is now considered a standard procedure for patients with renal stones. The common complications after PCNL include sepsis, iatrogenic injury to adjacent structures (such as the liver, spleen, and bowel), failed renal access, perforation of the renal pelvis, pleural effusion, and pneumothorax [5]. The most significant complication associated with this procedure is hemorrhage. Severe bleeding can occur due to needle puncture, tract dilation, or nephrostomy tube placement [3]. The close association of the renal veins with the renal pelvis and major posterior calyces makes them susceptible to damage during the steps of PCNL [6].

In this case, PCNL was performed for renal calculi, and the nephrostomy tube was inserted for drainage of the collecting system. A DJ stent was placed to maintain the patency of the ureter after the procedure. Five hours after the placement of the nephrostomy tube, the tube was unclamped to observe urine output and the passage of residual stones. Upon unclamping, gross hematuria of approximately 500–1000 mL was observed. At that time, the patient was stable, so the PCN tube was kept clamped, and the patient was closely monitored alongside fluid replacement. Upon unclamping the PCN tube for the second time, similar gross hematuria with a blood loss of 500–1000 mL was observed. The patient subsequently became hemodynamically unstable and was shifted to the HDU, where 4 units of packed cell volume (PCV) and FFP were administered to maintain hemodynamics. Investigations were performed to identify the possible complications. An ultrasound was performed, but no significant findings were observed. On CT angiography, the nephrostomy tube was found to be in the renal vein, with its tip only 2 mm away from the IVC (as shown in Figure 5).

There are two possible ways to manage a misplaced nephrostomy tube: conservative and surgical. In our case, the patient was successfully managed using conservative treatment. In cases involving misplacement of a nephrostomy tube, depending on the postoperative time elapsed, nephrostomy tube transposition is advised under fluoroscopic guidance, and the surgical team should be prepared for emergency surgery if required [7]. Using fluoroscopic guidance with contrast, the nephrostomy tube was completely withdrawn, as the patient was hemodynamically and vitally stable. Repeated blood tests (Tables 1 and 2) and ultrasounds were performed. The patient developed slight hematuria, which was detected through the Foley’s catheter, but it was managed by hydrating the patient under the cover of a diuretic. The patient was kept under observation for 48 h to monitor for any possible recurrent hematuria, but none occurred. The patient was discharged successfully. The data from these and other similar publications are summarized in Table 3.

| Author | Age/sex | Operation type | Catheter type | Location | Catheter withdrawal | Subsequent treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dias Filho et al. [8] | 63/F | PCNL | Foley catheter | Left renal vein | 1-step under fluoroscopy | Second PCNL |

| Wah et al. [9] | 54/M | PCNL | Nephrostomy tube | Renal vein | 2-step under fluoroscopy | Exploratory |

| Mazzucchi et al. [7] | 52/M | PCNL | Nephrostomy tube | Renal vein | 1-step under fluoroscopy | No |

| Mazzucchi et al. [7] | 35/M | PCNL | Nephrostomy tube | Renal vein, IVC | 2-step under fluoroscopy | No |

| Li et al. [10] | 32/M | PCNL | Nephrostomy tube | Renal vein, IVC | 2-step under fluoroscopy | No |

| Wang et al. [11] | 66/M | PCNL | Nephrostomy tube | Renal vein | 1-step under fluoroscopy | No |

| Kotb et al. [6] | 50/M | PCNL | Foley catheter | Renal vein, IVC | 1-step open pyelotomy | Open pyelotomy |

| Chen et al. [12] | 42/M | PCNL | Nephrostomy tube | Renal vein, IVC | 2-step under CT guide | Second PCNL |

| Chen et al. [12] | 38/F | PCNL | Nephrostomy tube | Renal vein, IVC | 2-step under fluoroscopy | Simultaneous PCNL |

| Chen et al. [12] | 48/M | PCNL | Nephrostomy tube | Renal vein | 1-step under ultrasound | Second PCNL |

Nomenclature

-

- CT

-

- Computed tomography

-

- IVC

-

- Inferior vena cava

-

- PCNL

-

- Percutaneous nephrolithotomy

Consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient has given his consent for his images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that his name and initials will not be published, and due efforts will be made to conceal his identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. Any additional data or materials can be made available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.