Polymicrobial Osteomyelitis in a Patient With Isolation of Trueperella bernardiae: A Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

Background: Trueperella bernardiae is a Gram-positive rod that has been described as an opportunistic pathogen in immunocompromised patients. In a significant number of documented cases, infections with Trueperella bernardiae have been associated with polymicrobial infections, which highlight the fact that important bacteria–bacteria relations might be involved in the natural course of these infections, especially in patients with chronic disease courses and a history of multiple antibiotic treatments.

Case Presentation: We present a case of a 24-year-old woman with a 3-year history of a chronic pressure ulcer on the right foot associated with varus and cavus deformity. As per relevant medical history, she was positive for multiple wound healing sessions with wound debridement and a large number of antibiotic treatments with minimal improvement. Microbiological cultures were taken from the wound, and a soft tissue infection diagnosis was initially made. Empirical treatment was initiated with levofloxacin. At 48 h, cultures were positive for Providencia stuartii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus penneri, Streptococcus agalactiae, and Trueperella bernardiae, and the susceptibility test was performed. Three weeks later, the symptoms progressed to purulent exudate of the wound and foul-smelling with the positive probe-to-bone test. Diagnosis was changed to polymicrobial osteomyelitis, and antibiotic therapy with ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was prescribed for a 4-week course of treatment, achieving the complete remission of symptoms.

Conclusions: Trueperella bernardiae represents an emerging bacterium that can be isolated in various clinical presentations. On osteoarticular infections, the presence of comorbidities, mobility limitations, and a history of multiple antibiotic treatments may be determinant. Their isolation as part of polymicrobial infections highlights relevant interspecies interactions. Research is still lacking in determining standardized methodologies for susceptibility testing and specific clinical breakpoints to guide clinical decisions.

1. Background

Trueperella bernardiae is a Gram-positive rod, predominantly coccobacilli, non-spore-forming, non-motile, facultatively anaerobic, catalase-negative, oxidase-negative, and indole-negative bacterium, with colony diameters ranging from 0.5 mm to 1.5 mm [1–4]. It can be found as a commensal in the human skin [3–6], oropharynx [3–5], and urogenital tract microbiota [2, 3]. The pathogenic role of T. bernardiae in human disease has not been established due to difficulties related to its isolation [2, 6, 7], its consideration as a contaminant in cultures [2, 7], and its low frequency as a part of a pathogenic process as well [4, 8]. However, the use of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) technology has allowed clinical microbiologists to identify it. Therefore, it is increasingly documented in the literature [3].

Some authors have classified this microorganism as an opportunistic pathogen [1, 9], in which the presence of comorbidities related to an immunocompromised state, such as chronic degenerative diseases [3, 10–15] or reduced mobility [7, 8, 16–18], is frequently reported. In some cases, a history of multiple surgical procedures [7, 8, 19, 20] or prolonged antibiotic treatment courses [10, 21, 22] appears to be a common factor for infection with this pathogen, especially for polymicrobial infections. Therefore, the clinical context seems to be the most relevant component of T. bernardiae infection.

To our knowledge, only 39 cases associated with human infection have been reported in the medical literature, which consist of 4 cases of urinary tract infection [2, 10, 19, 20], 8 cases of joint and prosthesis infection (hip and knee) [2, 7, 11, 12, 23–25], 10 cases of soft tissue and wound infection [1, 2, 4–6, 8, 13–15], 13 cases of bacteremia or sepsis [2, 3, 9, 16, 17, 21, 26–28], 2 cases of cerebral abscess [22, 29], 1 case of endocarditis [18], and 1 case of Lemièrre syndrome [30].

A notable number of articles have documented cases of Trueperella bernardiae infection where more than one microorganism has been involved, in which patients have long antibiotic treatments due to the presence of chronic infections. These observations suggest a potential association between Trueperella bernardiae and the establishment of interspecies relationships that may contribute to its pathogenicity. Nevertheless, the precise nature of these relationships remains to be established in the context of this infection.

Here, we present a case of a young woman with a history of chronic soft tissue infection that later evolved into polymicrobial osteomyelitis caused by Trueperella bernardiae infection. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this case report.

2. Case Report

A 24-year-old woman was referred to our institution because of a 3-year history of soft tissue infection in the right lower limb associated with varus foot deformity. She had received multiple antibiotic treatments and wound-healing sessions with minimal improvement. As part of her relevant medical history, the patient underwent myelomeningocele correction at birth and numerous correcting surgeries in both feet for varus and cavus deformity. The last correction surgeries were in 2002 for a tenotomy in the left lower limb and instrumentation of the right foot with placement of the osteosynthesis material in 2017. Otherwise, her past medical history was unremarkable.

Physical examination revealed varus of the right lower limb with cavus deformity of the foot. A 7 × 2 × 3 cm painful ulcer was noted in the lateral aspect of the right heel with well-defined margins, a clean bottom, and no evidence of purulent exudate. Sensitivity and range of motion were preserved without vascular involvement. The patient denied any history of fever, dizziness, nausea, or vomiting. The laboratory included a blood leukocyte and platelet count of 7700/mm3 and 639,000/mm3, respectively, C-reactive protein (CRP) levels of 2.95 mg/L, and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 20 mm/hr. Due to multiple antibiotic courses, clinical history, and adverse wound evolution, it was decided to obtain a biopsy for microbiological cultures. The specimens were inoculated onto 5% blood sheep agar (BD DIFCO, Beckton, Dickinson and Company, US), MacConkey agar (BBL, Beckton, Dickinson and Company, US), both under aerobic conditions, and phenylethyl alcohol agar (PEA) (TM Media, Bhiwadi), under anaerobic conditions, at 37°C. Preliminary Gram staining of the exudate revealed abundant Gram-negative bacilli and Gram-positive cocci. A primary diagnosis of soft-tissue infection was made. The wound was initially treated locally with Prontosan (B|Braun) solution washings with surgical debridement.

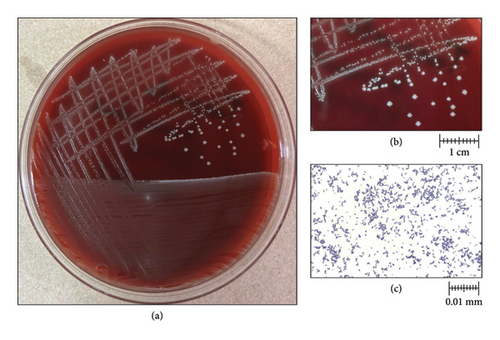

Three Gram-negative bacilli were isolated from aerobic MacConkey agar culture, and one Gram-positive cocci was isolated from 5% blood sheep agar two days after culture incubation. Species identification with MALDI-TOF MS, Vitek MS (BioMérieux, France) technology revealed the presence of Providencia stuartii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus penneri, and Streptococcus agalactiae. On PEA, small, whitish, nonhemolytic, and round colonies were observed (Figures 1(a) and 1(b)). Gram staining revealed Gram-positive coccobacilli (Figure 1(c)), which later were identified as Trueperella bernardiae by Vitek MS [31]. The identification was confirmed by Sanger sequencing targeting the 16S rRNA gene.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for susceptibility tests was performed by the broth microdilution technique Vitek2 System (BioMérieux, MarciÈtoile, France) in all isolates, with the exception of Trueperella bernardiae. Providencia stuartii showed resistance to ampicillin-sulbactam (> 32 μg/mL) and ciprofloxacin (2 μg/mL), and Proteus penneri showed intermediate resistance to imipenem (2 μg/mL). Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Streptococcus agalactiae were pansusceptible.

Trueperella bernardiae MIC was determined by the agar dilution method in Brucella agar supplemented with hemin (5 μg/mL), vitamin K1 (1 μg/mL), and 5% sheep blood. As no specific clinical breakpoints have been established for resistance to Trueperella bernardiae, the “MIC breakpoints for Anaerobes” of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guides were used [32]. Trueperella bernardiae MIC values are shown in Table 1. Considering microbiological isolations, a severe polymicrobial soft tissue infection diagnosis was made, and empiric antibiotic treatment with levofloxacin (750 mg of PO daily for 7 days) was initiated.

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/mL) | Antibiotic | MIC (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillin | S (≤ 0.25) | Ertapenem | S (≤ 2) |

| Ampicillin | S (≤ 0.25) | Amikacin | R (≥ 8) |

| Ampicillin/sulbactam | S (≤ 4/2) | Ciprofloxacin ∗ | R (2) |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate | S (≤ 2/1) | Levofloxacin ∗ | R (4) |

| Ceftriaxone | S (≤ 8) | Vancomycin ∗∗ | NA (≤ 2) |

| Cefoxitin | S (≤ 8) | Piperacillin/Tazobactam | S (≤ 16/4) |

| Imipenem | S (≤ 2) | Metronidazole | R (≥ 32) |

| Meropenem | S (≤ 2) | Tetracycline | S (≤ 2) |

- Note: The agar dilution method was used for minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determinations. Susceptibility interpretation was guided by “MIC breakpoints for Anaerobes” of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI).

- ∗Susceptibility interpretation guided by EUCAST PK/PD (non-related species) clinical breakpoints.

- ∗∗Clinical breakpoints for MIC interpretations are not standardized for this antibiotic by any guide.

Three weeks later, a medical assessment by the Infectious Diseases staff showed a purulent exudate and a foul-smelling of the wound with a positive probe-to-bone test. The antibiotic therapy was changed to ciprofloxacin (500 mg of PO q8h) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg of PO q8h) for 4 weeks as polymicrobial osteomyelitis was established.

Fourteen days later, the patient showed symptoms of dyspepsia and decided to discontinue treatment on a personal basis. On clinical assessment, a significant wound improvement was noted, with a reduction in size to 4 × 3 × 2 cm, cleaned margins, and no purulent exudate. The importance of continuing treatment after 1 month was emphasized to the patient. Estericide solution (ESTERIPHARMA) washings were performed with wound debridement, and KitosCell gel (Cell Therapy and Technology) and Sorbact dressings (BSN medical) were applied.

The treatment plan was accomplished, and total wound closure was observed. On physical examination, there was no evidence of exudates or fistulous tracts.

Eight months after the suspension of antibiotic treatment, the patient’s progress continued to be satisfactory. The computed tomography (CT) scan had documented the absence of data suggesting infection, and the orthopedic surgeon scheduled her for right tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis with a retrograde intramedullary nail for cavus deformity completion of treatment.

3. Discussion

Trueperella bernardiae is described as part of the normal microbiota of the skin, oropharynx, and urinary tract [3]. Since its description in 1995, its classification has been widely changed with the emergence of next-generation sequencing technologies (NGS) [33]. Originally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classified it as “Coryneform group 2” bacteria [34], given their differences from the group 1 and group 4A-Coryneform bacteria. They tested negative for catalase, esculin hydrolysis, nitrogen reduction, triple sugar iron, and gelatin hydrolysis. Then, in 1995, Funke et al. [35] performed the phenotypic characterization that led to their integration into the genus Actinomyces. Two years later, Ramos et al. [33] analyzed the hypervariable regions V1-V4 of the 16S ribosomal gene and reclassified Actinomyces bernardiae into the Arcanobacterium genus. It was Yassin et al. [36] who in 2011 finally proposed the conformation of the Trueperella genus where Arcanobacterium bernardiae was included.

Clinical presentations of Trueperella bernardiae infection have been observed to vary considerably, encompassing a spectrum of manifestations ranging from severe conditions, such as necrotizing fasciitis, brain abscesses, or bacteremia, to less severe forms, including soft tissue infections, bone and prosthetic joint infections, or urinary tract infections (Table 2). Some others have reported cases of endocarditis or Lemièrre syndrome; however, these presentations are rare. On the other hand, it seems that Trueperella bernardiae infection occurs in an opportunistic manner, frequently associated with comorbidities, such as obesity [13, 17], type 2 diabetes mellitus [9, 13, 26], multiple surgical interventions [6–8, 23, 24], cancer [3, 5, 12, 15, 18], decreased functional status [27, 28], and history of past infections [21–29].

| Author | Sex/age | Diagnosis | Clinical characteristics | Sample | Culture | Isolates | Identification method | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ieven et al. 1996 (Belgium) [19] | 69 years/male | Urinary tract infection/perirenal abscess/sepsis | P: fever, leukocytosis, bilateral hydronephrosis, nephrolithiasis, and left perirenal abscess. Not pyuria or bacteriuria | Urine from nephrostomy and blood cultures. | Both positive at 72 h | Actinomyces bernardiae | Biochemical identification | Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, 13 days |

| RCH: incomplete neurinoma resection in 1975, 1982, and 1985; neurogenic bladder dysfunction; and uretero-ileocutaneostomy in 1987 | ||||||||

| Adderson et al. 1998 (US) [11] | 19 years/female | Right hip infection and avascular necrosis | P: 3 days history of right hip and knee pain, fever, limitation of motion, and deteriorating renal function | Right hip aspirate | Positive at 5 days | Arcanobacterium bernardiae | Fatty acid profile/biochemical identification | Clindamycin, 6 weeks |

| RCH: 4-year history of treatment with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide for glomerulonephritis secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus and avascular necrosis of left hip | ||||||||

| Lepargneur et al. 1998 (France) [20] | 75 years/male | Urinary tract infection | P: history of right back pain, fever, dilatation of inferior right ureter, calcified stones | Urine from nephrostomy | Positive at 48 h of incubation | Arcanobacterium bernardiae | API coryne system/biochemical identification/16S sequencing | First: Netilmicin, cefixime, 5 days |

| RCH: urothelial carcinoma in1985, radical cystoprostatectomy, ureteral duplication, and ureteroileal anastomosis | Second: amoxicillin, time not specified | |||||||

| Bemer et al. 2009 (France) [8] | 63 years/male | Infection in the lower lib | P: Persistent wound drainage in the left knee | Peroperative specimens | Positive at 96 h | Arcanobacterium bernardiae/Staphylococcus aureus | API coryne system/biochemical identification | Clindamycin and fusidic acid, 3 weeks |

| RCH: tuberculosis arthritis of the knee, arthrodesis and femur lengthening, avascular necrosis of the bone and sequestrum, Pipeneau’s technique, and bone grafting. For 30 years, recurrent swellings, which required surgical debridements and multiple antibiotic therapies | ||||||||

| Loïez et al. 2009 (France) [23] | 78 years/male | Prosthetic joint infection (hip) | P: left lower limb hematoma secondary to trauma | Hematoma, muscle, femur, and acetabulum | Positive at 48 h | Arcanobacterium bernardiae | API coryne strip/16S sequencing | Rifampicin, ofloxacin, 12 weeks |

| RCH: left total hip prosthesis 27 years previously. No chronic diseases | ||||||||

| Clarke et al. 2010 (USA) [13] | 62 years/female | Abdominal necrotizing fasciitis | P: 3 days history of left lower quadrant abdominal pain, redness of the skin, tender mass on the skin, and fever | Purulent drainage | Positive at 48 h | Arcanobacterium bernardiae/Morganella morganii | 16 S sequencing | Vancomycin, aztreonam, piperacillin-tazobactam, time not specified |

| RCH: type 2 DM, neuropathy, obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, COPD, osteoarthritis, depression, and tinea pedis | ||||||||

| Sirijatuphat et al., 2010 (Thailand) [10] | 60 years/male | Urinary tract infection (kidney abscess and perinephric abscess) and thoracic empyema | P: 3-week history of fever, dysuria, left loin pain, and weight loss. 1-week prior admission progressive breathlessness | Purulent drainage and pleural effusion | Not specified | Arcanobacterium bernardiae | 16S sequencing |

|

| RCH: poor controlled type 2 DM and several years of left renal stones | ||||||||

| Weitzel et al. 2011 (Chile) [16] | 72 years/female | Bacteremia secondary to sacral pressure ulcer infection | P: 2 days history of fever, chills, anorexia, and progressive prostration. At admission: hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnea, mental impairment, and sacral pressure ulcer | Blood specimens from surgical debridement | Both positive at 48 h |

|

API coryne system/16S sequencing | Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, 6 days |

| RCH: Alzheimer disease, hospitalization secondary to chronic pressure ulcers, and infection 6 months prior presentation | ||||||||

| Otto et al. 2013 (France) [17] | 78 years/female | Sacral pressure ulcer and bacteremia | P: fever (40°C), tachycardia, polypnea, and sacral ulcer | Sacral ulcer, urine, and blood |

|

Trueperella bernardiae/Bacteroides fragilis/Enterococcus. avium | 16S sequencing | Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, 10 days |

| RCH: obesity, superinfected chronic pressure ulcers in lower limbs, and multiple antibiotic treatments | ||||||||

| Parha et al. 2015 (UK) [22] | 68 years/female | Brain abscess | P: confusion, vomiting, slurry speech, and double incontinence | Purulent drainage | Not specified | Trueperella bernardiae/Peptoniphilus harei | 16S sequencing | Ceftriaxone, 12 weeks |

| RCH: diabetes insipidus, rheumatoid arthritis, long-standing chronic suppurative otitis media, mastoiditis, and multiple antibiotic schemes | ||||||||

| Schneider et al. 2015 (Denmark) [9] | 45 years/male | Bacteremia secondary to diabetic foot infection | P: diabetic foot, pressure ulcers in lower limbs, fever (38.2°C), and tachycardia | Purulent discharge | Positive at 48 h | Trueperella bernardiae/Peptostreptococcus lacrimalis | MALDI-TOF MS/16S sequencing | Amoxicillin, 14 days |

| RCH: obesity, type 2 DM, atherosclerosis, neuropathy, chronic foot ulcers, and amputation of two toes of the right foot | ||||||||

| Gilarranz et al. 2016 (Spain) [7] | 73 years/female | Prosthetic joint infection (knee) | P: chronic pain of the left lower limb, hematoma in the left knee, and no fever | Synovial fluid | Positive at 48 h | Trueperella bernardiae | MALDI biotyper/VITEK MS | Ciprofloxacin, 14 days |

| RCH: bilateral knee osteoarthritis, bilateral total knee replacement, surgical site infection, and patellar tendon necrosis | ||||||||

| Rattes et al. 2016 (Brazil) [1] | 24 years/female | Surgical site infection in laparoscopic cholecystectomy | P: fever, abdominal pain, and periumbilical purulent discharge | Purulent discharge | Positive at 96 h | Trueperella bernardiae | MALDI-TOF | Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, 7 days |

| RCH: laparoscopic cholecystectomy 7 days before | ||||||||

| VanGorder et al. 2016 (USA) [14] | 77 years/female | Soft tissue infection (abscess) | P: 2 weeks indurated lesion on the back, painful, with purulent secretion | Purulent discharge | Positive at 48 h | Trueperella bernardiae | MALDI-TOF MS | Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, 10 days |

| RCH: lesion 2 years before with the same characteristics; resolved with antibiotic empiric treatment. No chronic diseases | ||||||||

| Cobo et al. 2017 (Spain) [15] | 69 years/female | Surgical site infection | P: fever, pain, and purulent discharge on the surgical site | Purulent drainage | Positive at 72 h | Trueperella bernardiae | MALDI-TOF MS/16S sequencing | Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, 7 days |

| RCH: colostomy relocation 7 days before the presentation, rectal cancer, multiple abdominal surgeries, and recurrent episodes of pericolostomy eventration | ||||||||

| 70 years/female | Soft tissue infection (inguinal granuloma) | P: fever, pain, and purulent discharge | Purulent discharge | Positive at 24 h | Trueperella bernardiae/Escherichia coli | MALDI-TOF/16S sequencing | Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, 7 days | |

| RCH: metastatic ovarian cancer, chemotherapy schemes (carbo-taxol, caclyx + carbo-taxol + topotecan), and resection of inguinal adenopathies | ||||||||

| Gowe et al. 2018 (US) [24] | 57 years/male | Olecranon bursitis | P: fever and purulent discharge of right olecranon | Intraoperative specimens | Positive at 24 h | Trueperella bernardiae | Vitek 2/MALDI-TOF | Doxycycline, 14 days |

| RCH: hypertension, gout, bursectomy, and tenotomy 2 years before presentation, farmer | ||||||||

| Lawrence et al. 2018 (UK) [2] | 45 years/male | Bacteremia secondary to septic thrombophlebitis in a IV drug user | P: fever, tachycardia, and necrotic abscess at the injection site. Multiple purulent lesions in the thigh and calves | Purulent discharge and thrombus | Positive at 48 h | Trueperella bernardiae | MALDI.TOF MS/16S sequencing | Amoxicillin plus amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, 4 weeks |

| RCH: IV drug user (heroin and cocaine), lick needle prior IV injection | ||||||||

| 56 years/male | Bone infection | P: Not specified | Bone specimen | Not specified | Trueperella bernardiae | MALDI-TOF MS | Not specified | |

| RHC: Diabetic foot infection | ||||||||

| 42 years/female | Urinary tract infection | P: Not specified | Urine | Not specified. | Trueperella bernardiae/Enterococcus faecalis | MALDI-TOF MS | Not specified | |

| RCH: Ileal conduit | ||||||||

| 32 years/female | Soft tissue infection | P: Not specified | Purulent discharge | Not specified | Trueperella bernardiae | MALDI-TOF MS | Not specified | |

| RCH: Breast abscess | ||||||||

| 42 years/male | Bone infection | P: Not specified | Bone specimen | Not specified. | Trueperella bernardiae/Citrobacter koseri/Corynebacterium sp. | MALDI-TOF MS | Not specified | |

| RCH: Diabetic foot infection | ||||||||

| 43 years/male | Bacteremia | P: Not specified | Blood culture | Not specified | Trueperella bernardiae/Fusobacterium gonidiaformans/Actinomyces funkei | MALDI-TOF MS | Not specified | |

| RCH: Septic thrombophlebitis in the injection drug user | ||||||||

| 50 years/female | Bacteremia | P: Not specified | Blood culture | Not specified. | Trueperella bernardiae/Escherichia coli | MALDI-TOF MS | Not specified | |

| RCH: Metastatic cervical cancer | ||||||||

| 32 years/male | Bacteremia | P: Not specified | Blood culture. | Not specified. | Trueperella bernardiae/Fusobacterium gonidiaformans | MALDI-TOF MS | Not specified | |

| RCH: Still disease | ||||||||

| Najwa et al. 2018 (USA) [18] | 70 years/female | Polymicrobial endocarditis | P: 2 weeks history of low-grade fever and fatigue. At ER, hypotension and supraventricular. Catheter insertion erythematosus | Blood culture (central and peripheral) | Not mentioned | Trueperella bernardiae/Globicatella sanguinis | MALDI-TOF MS/sequencing | Meropenem and gentamicin, 6 weeks |

| RCH: cervical cancer, stent failure, and end-stage renal disease. Stents changed 3 months prior to presentation | ||||||||

| Calatrava et al. 2019 (Spain) [4] | 39 years/female | Soft tissue infection (abscess) | P: 10 days history of right breast pain and swelling | Purulent discharge | Positive at 48 h | Trueperella bernardiae/Actinotignum sanguinis | MALDI-TOF MS | Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, 10 days |

| RCH: No chronic diseases | ||||||||

| Pan et al. 2019 (US) [29] | 5 years/male | Cerebral abscess secondary to suppurative otitis media | P: On the fifth day after bilateral tympanostomy: left otalgia, emesis, fever, and tonic-clonic movements | Purulent discharge form tympanostomy and cerebral abscess | Positive at 7 days |

|

MALDI-TOF MS |

|

| RCH: acute-on-chronic left otitis media, bilateral tympanostomy tube placement, and multiple courses of antibiotics | ||||||||

| Roh et al. 2019 (Korea) [26] | 83 years/female | Bacteremia | P: fever, hypotension. K. pneumoniae UTI 3 days prior presentation | Blood culture | Positive at 96 h | Trueperella bernardiae/Staphylococcus aureus | MALDI-TOF MS/16 sequencing | Teicoplanin, 11 days |

| RCH: type 2 DM, cerebrovascular disease, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation | ||||||||

| Casanova, et al. 2019 (Spain) [5] | 43 years/female | Soft tissue infection (abscess) | P: 2 days history of fever, pain, and swelling of the right lower limb | Purulent discharge | Positive at 48 h | Trueperella bernardiae | MALDI-TOF MS | Ciprofloxacin, 14 days |

| RCH: 7 years history of chronic myeloid leukemia treated with nilotinib | ||||||||

| Tang et al. 2021 (US) [6] | 71 years/male | Soft tissue infection (abscess) | P: Pain, rubor, and swelling and purulent discharge from surgical scar on his right hip. A bulge was noticed 6 weeks before the presentation | Purulent drainage, and swabbing of fat and soft tissue form surgery | Not specified | Trueperella bernardiae | MALDI-TOF MS |

|

| RCH: Right hip arthroplasty performed 2 years before presentation | ||||||||

| Casale et al. 2021 (Italy) [3] | 78 years/female | Bacteremia secondary to gynecological surgery | P: fever and 5 days history of abdominal pain. Total vulvectomy with bilateral inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy was performed 2 months prior presentation | Swabbing from surgical wound | Positive at 26–74 h | Trueperella bernardiae/Bacteroides fragilis/Enterococcus avium | MALDI-TOF MS/16S sequencing. | Clindamycin plus metronidazole, 14 days |

| RCH: breast cancer treated with chemotherapy (QUART) 6 years before presentation, keratinizing squamous carcinoma, and hysterectomy | ||||||||

| Stone et al. 2021 (Australia) [25] | 70 years/female | Recurrent periprosthetic joint infection | P: periprosthetic joint infection 4 months after hip replacement. Symptoms not mentioned | Collection drainage | Not specified |

|

Not specified |

|

| RCH: not specified | ||||||||

| Matsuhisa et al. 2023 (Japan) [27] | 94 years/female | Sepsis following acute pyelonephritis | P: high-level fever (40°C), dyspnea, chills, and hypotension. Labs: leukocytosis, high PCR levels (12.31 mg/dL), leukocyturia, and bacteriuria. CT scan showed stones in both kidneys |

|

Not specified. |

|

MALDI-TOF MS/16S sequencing |

|

| RCH: hypertension, chronic heart failure, dementia, chronic kidney disease, osteoporosis, spinal cord compression fracture, and left femoral transverse fracture. Bedridden since then | ||||||||

| Kumai et al. 2023 (Japan) [30] | 60 years/female | Otogenic variant of Lemierre syndrome | P: 6 months otorrhea and headaches and fever (40.5°C) 4 days prior presentation. At ER, hypotension, seizures, neck stiffness, and jolt accentuation. Labs showed leukocytosis, elevated PCR, and severe thrombocytopenia. Cerebrospinal fluid with neutrophilia and low glucose. MRI showed subdural empyema and sigmoid sinus thrombosis | Blood culture | At day 11 | Trueperella bernardiae | Not specified |

|

| RCH: no comorbidities | ||||||||

| Mazin et al. 2023 (USA) [28] | 50 years/male | Multifactorial bacteremia in a paraplegic patient | P: several day history of abdominal pain and malaise. At ER hypotension, leukocytosis, AKI, and hyponatremia. CT scan showed nonobstructing bilateral kidney stones, right hydronephrosis, and abdominal collection |

|

Positive at 72 h |

|

Mass spectrometry |

|

| RCH: paraplegia, ischial pressure ulcer, bilateral staghorn struvite calculi, nephrostomy (multiple cystoscopies and bilateral stent placement), and type 2 DM | ||||||||

| Chapman et al. 2023 (USA) [21] | 45 years/male | Bacteremia due to PICC- associated infection in a paraplegic patient | P: severe muscle spasms, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. CT scan showed left hip fluid collection | Blood culture | Positive at 72 h | Trueperella bernardiae/Staphylococcus aureus | MALDI-TOF |

|

| RCH: T4-T5 spinal cord injury and multiple hospitalizations due to infections that required extended courses of antibiotics | ||||||||

| Saleem et al. 2023 (USA) [12] | 76 years/male | Pelvic osteomyelitis and sepsis | P: 3 weeks history of bilateral lower extremity weakness, lethargy, and chills. At ER, fever and hypotension | Blood culture | Positive at 48 h | Trueperella bernardiae | Not specified |

|

| RCH: prostate cancer, prostatectomy, chronic urinary retention with incontinence, and chronic foley with intermittent self-catheterization | ||||||||

| Delaye et al. 2024 (Mexico) | 24 years/female | Bone infection | P: pain, 3-year history of pressure ulcer on the right heel treated with multiple antibiotic schemes. Ulcer with well-defined margins, clean bottom, and initially no presence of purulent exudate. No history of fever, sensitivity, vascular, or motion compromised | Biopsy from ulcer | Positive at 48 h | Trueperella bernardiae/Providencia stuartii/Pseudomonas aeruginosa/Proteus penneri/Streptococcus agalactiae | MALDI-TOF MS/16s sequencing | Ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 4 weeks |

| RCH: myelomeningocele, multiple correcting surgeries for cavus foot deformity in both feet, tenotomy in the left lower limb, and instrumentation on the right foot | ||||||||

- Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; DM, diabetes mellitus; ER, emergency room; P, presentation; RCH, relevant clinical history.

The methods used to identify Trueperella bernardiae have undergone significant developments in the last years. NGS has proven invaluable in differentiating between various Trueperella species, establishing itself as the gold standard [37]. However, the utilization of methodologies such as MALDI-TOF has proven to be beneficial, as they facilitate identification in a shorter time [31]. Following the work of Hijazin et al., the validation of databases for identifying Trueperella bernardiae has commenced since 2012. From this moment, almost all documented cases of Trueperella bernardiae infection after 2015 have employed this technology for identification with good concordance when confirming with 16S sequencing. Overall, it appears that mass spectrometry is an effective method for the identification of Trueperella bernardiae and should be considered for the initial approach.

Trueperella bernardiae natural course infection is complicated to establish, given the coexistence with polymicrobial infections. However, in patients with osteoarticular and periprosthetic infection, it appears to be associated with infection courses of more chronicity. For example, Bemer et al. [8] reported in 2009 a case of a 63-year-old man who presented for almost 30 years with recurrent episodes of infection and knee swelling. In his last relapse, both Staphylococcus aureus and Trueperella bernardiae were isolated and required surgical debridement and antibiotic therapy. Another case was reported by Otto et al. [17], involving a 78-year-old woman with a history of a pressure ulcer in the sacral region. Clinically relevant history was positive for diabetes mellitus, obesity, and multiple episodes of superinfected ulcers in both lower limbs. Three strains were isolated from the wound: Bacteroides fragilis, Enterococcus avium, and Trueperella bernardiae. The patient developed bacteremia secondary to Bacteroides fragilis dissemination, which later resolved with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid for 10 days. In our case, the patient had a chronic ulcer with a protracted evolution, which was previously treated on multiple occasions with antibiotic therapy with no improvement. It was also presented in the context of a polymicrobial infection. Considering the similarity to the previously mentioned cases, it is expected that Trueperella bernardiae infection represents a long-standing infection that might coexist with other microorganisms at the time of the diagnosis, where an immunocompromising state plays an important role in the host’s susceptibility. The relationship between Trueperella bernardiae and anaerobic bacteria needs to be considered. In most of the cases where a polymicrobial infection was reported, other bacteria, such as Bacteroides fragilis [17], Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron [28], Fusobacterium gonidiaformans [2], Peptoniphilus harei [22], Peptostreptococcus lacrimalis [9], or Actynomices spp. [2], were also isolated. This particularity may correlate with the chronicity observed in clinical presentations that include isolates of anaerobic bacteria and the presence of Trueperella bernardiae, where, as noted above, it is frequently reported as part of chronic infections. Another important observation that might contribute to the polymicrobial nature of these infections is the relation between Trueperella bernardiae and Staphylococcus aureus. Almost 3 cases have been reported in the literature where both microorganisms were isolated as part of a soft tissue infection that later evolved into bacteremia. It is known that Staphylococcus aureus establishes relations with other microorganisms such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa. For example, in cases of pressure ulcers, P. aeruginosa is found to grow in the basal layers of the ulcer, and S. aureus grows more superficially [38]. By this, whether Trueperella bernardiae might benefit from S. aureus or P. aeruginosa warrants further investigations. Some potential mechanisms that could be involved in the development of this polymicrobial infection include the following: (i) the formation of bacterial biofilms, (ii) the presence of commensal interactions between the bacteria involved in the infection, and (iii) interspecies genetic exchange promoting antimicrobial resistance [38].

Antimicrobial treatment of Trueperella bernardiae infections remains a discussion topic, mainly because of the lack of consensus for antibiotic therapeutic regimens. According to literature-reported cases, the pharmacological approaches used in the susceptibility tests with the diffusion gradient epsilometry method (E-test) had been widely variable. This has resulted in difficulty to standardize MICs that are useful to establish clinical breakpoints for therapeutic decisions. Resistance to at least 16 drugs has been reported in the literature; among those that stand out are erythromycin [1, 2, 4, 7, 26], clindamycin [1, 4, 7], penicillin G [23, 26], cefotaxime [30], sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim [4, 23, 27], amikacin [23], norfloxacin [17], daptomycin [28], phosphomycin [17], ciprofloxacin [15], levofloxacin [27], meropenem, imipenem, moxifloxacin [5], gentamicin [30], and metronidazole [11] (Supporting Table 1). This interpretation must be taken with caution because, to date, neither the EUCAST nor the CLSI guidelines have yet established specific clinical breakpoints for Trueperella bernardiae. Furthermore, there is no consensus regarding the most appropriate methodology for testing susceptibility. Considering this, dilution methods such as macrodilution, microdilution, or agar dilution represent a good approach for the determination of antimicrobial susceptibility for unknown clinical breakpoint bacteria, as in the case of Trueperella bernardiae [39]. These methods offer an advantage over epsilometry, a diffusion method, as they permit a more precise control of the inoculum size. In this sense, the number of colony-forming units (CFU) determined by McFarland densitometry and the volume to be used during the inoculation can be more accurate with dilution methods than diffusion methods, where a swab is used to spread the inoculum on the agar plate. For this reason, diffusion methods for susceptibility testing reports might be a better approach for clinical breakpoint standardization.

Despite the lack of clinical breakpoints, the therapeutic approach to Trueperella bernardiae infection should prioritize the selection of an antimicrobial regimen that demonstrates optimal penetration into the affected tissue and provides good coverage against other microorganisms that may accompany the infection.

All treatments used to manage infections involving Trueperella bernardiae have been effective. In general, the antibiotic most frequently prescribed is amoxicillin with clavulanic acid for 7–14 days, depending on the clinical context of each patient. There have been reported cases where the treatment was extended for over a month. For example, Loïez et al. [23] used a 12-week therapeutic scheme for a hip prosthetic joint infection. Pan et al. [29] used a 6-month scheme with amoxicillin to treat a 5-year-old child with a cerebral abscess, and Lawrance et al. [2] reported a 4-week scheme with amoxicillin to treat a patient with bacteremia. The treatment of Trueperella bernardiae infections will typically depend on the location of the infection, the presence of a monomicrobial or polymicrobial infection, and the susceptibility of the isolates. In consideration of the cases that have been published, the recommended treatment duration for bone and periprosthetic joint infections is between six and eight weeks [1, 7, 11, 23–25]. The use of quinolones [7], clindamycin [11], tetracyclines [24], or carbapenems [25] has been demonstrated to be adequate for the treatment of these infections. In contrast, the use of beta-lactams and beta-lactam inhibitors such as amoxicillin with clavulanic acid has been demonstrated to be an effective approach for the treatment of soft tissue infections [1, 2, 4–6, 8, 14, 15], urinary tract infections [2, 10, 19, 20, 27], and bacteremia [2, 3, 9, 12, 16, 21]. The recommended duration of treatment for these infections is 2–4 weeks, respectively. In the case of central nervous system infections, the use of 3rd generation cephalosporins and amoxicillin has been effective with a treatment duration of 3–6 months [22, 29]. Just one case of abdominal necrotizing fasciitis has been documented, in which treatment with piperacillin-tazobactam was effective [13].

In our case, Trueperella bernardiae showed resistance to clindamycin (MIC ≥ 8 μg/mL) and metronidazole (MIC ≥ 32 μg/mL), according to the CLSI clinical breakpoints for anaerobes, and resistance to levofloxacin (MIC 2 μg/mL) and ciprofloxacin (MIC 4 μg/mL), given the EUCAST PK/PD for nonrelated species (Table 1). With this in mind, the patient initially received levofloxacin for 7 days. Then, because of the worsening of symptoms, the treatment was switched to ciprofloxacin and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim for 4 weeks until complete remission was achieved. It is well established that fluoroquinolones are recommended for the treatment of pressure ulcers or ulcers associated with venous insufficiency [40], as they provide good coverage against Staphylococcus aureus and gram-negative bacilli. Furthermore, in the context of bone involvement, they are an excellent option due to their ability to penetrate in such tissue [41]. The initial failure in our case was likely attributed to the polymicrobial nature of the infection. We opted for ciprofloxacin switching because of its well-known antipseudomonal activity and its effectiveness against Proteus species, while trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was selected for its efficacy against both Streptococcus and Proteus species. In addition to levofloxacin, antibiotics from the macrolide family, such as azithromycin, and first-generation cephalosporins, such as cephalothin, teicoplanin, or gentamicin, can also be useful.

Despite the resistance observed in the Trueperella bernardiae isolate, treatment was sufficient to achieve the complete remission of symptoms up to 8 months after treatment discontinuation.

4. Conclusion

Trueperella bernardiae is a variable hemolytic, facultatively anaerobic, Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacterium that can be found in patients with an immunocompromised state. Its isolation in the context of a polymicrobial infection, is a common finding among the medical literature, and a long course of treatment might be necessary for complete remission of the symptoms. The use of the MALDI-TOF MS system for bacterial identification appears to be effective. There is a lack of consensus on the best method to determine the susceptibility testing for Trueperella bernardiae, and this can be seen reflected in the lack of standardized clinical breakpoints for clinical decisions. So, it is important to define which method is better to homogenize the data reported in similar cases. Moreover, the antimicrobials to be tested in this type of assay are still needed, which might be solved if intrinsic resistance mechanisms are evaluated experimentally.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal. The requirement of ethical approval for this case report was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study by the ethics committee of the Instituto Nacional de Rehabilitación.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Acknowledgments

The authors have nothing to report.

Supporting Information

Supporting Table 1 (part I and II) describes the susceptibility profiles of the clinical strains of Trueperella bernardiae reported in similar case reports consulted in the current work. The methodology employed by each author for susceptibility testing is specified at the top of the column. Additionally, the reference guidelines utilized for the interpretation of the results are at the bottom of the table.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.