Agromorphological and Physiological Trait Diversity in Ethiopian Mustard (Brassica carinata A. Braun) Germplasm

Abstract

Ethiopian mustard (Brassica carinata A. Braun) is a versatile oil crop cultivated for vegetable and oilseed production. Despite the availability of numerous landraces, a comprehensive understanding of their phenotypic diversity remains limited, hindering breeding efforts to improve the crop. This study evaluated 386 Ethiopian mustard accessions for 21 agromorphological and six physiological traits over two growing seasons using an augmented block design. This comprehensive analysis aimed to uncover the extent of phenotypic variation within the germplasm collection and identify promising genotypes with desirable traits for breeding. Significant variation (p ≤ 0.001) was found among accessions, highlighting their substantial phenotypic diversity. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed that the top 5 components explained 61.23% of the total variation, providing insights into the major contributors to phenotypic variability. Cluster analysis grouped the accessions into four distinct clusters, with the highest intercluster divergence (18.21) observed between clusters 3 and 4. This suggests the potential for selecting diverse genotypes across phenotypic groups, which could be valuable for broadening the genetic base of breeding programs. Cluster 2 exhibited the highest intracluster distance (6.71) and mean genetic distance (5.23), implying extensive agromorphological and physiological variability, valuable for breeding to develop cultivars with diverse traits. Overall, this study identified several superior performing genotypes: acc-192, acc-386, acc-1, acc-192, acc-377, acc-1, acc-235, acc-294, acc-302, acc-112, acc-331, acc-152, acc-55, and acc-72 characterized by high seed yields and oil content. These accessions are promising candidates for further improvement and incorporation into breeding programs. These findings reveal extensive genetic diversity in Ethiopian mustard and provide valuable insights for future breeding programs, highlighting the potential of conserving genetic resources to enhance the crop’s performance, adaptability, and versatility, ultimately supporting sustainable agriculture and alternative energy development initiatives.

1. Introduction

Ethiopian mustard (Brassica carinata A. Braun), also known as Gomen zer, Yehabesha gomen, Ethiopian rape, and Abyssinian mustard, is a vital oilseed crop with a 4000-year cultivation history in Ethiopia [1]. The crop is a self-pollinating annual plant belonging to the Brassicaceae family [2]. It demonstrates remarkable adaptability to diverse ecological conditions and plays a crucial role in Ethiopian agriculture, supporting over 3 million smallholder farmers [3, 4]. This crop is the third most important oilseed crop in Ethiopia, following nigerseed and flaxseed, with a total yield of 74,766.6 tons produced over 45,167.81 hectares [5].

In Ethiopia, B. carinata holds significant cultural and economic value [6, 7]. Its ground seeds are traditionally used to lubricate “injera“ baking pans, whereas young leaves serve as a vegetable relish [8]. The seeds also possess medicinal properties and are used in traditional beverages [9]. The oil extracted from B. carinata seeds has substantial industrial potential, primarily for biofuel production, owing to its high erucic acid content [10]. Furthermore, B. carinata serves as an excellent rotational and intercropping partner for various food crops, contributing to improved soil health and productivity [11–13]. As a cover crop, it mitigates soil erosion, reduces herbicide use, and promotes a nutrient balance [14]. Its resilience to harsh environments and pests makes it suitable for cultivation on marginal lands [15, 16]. The combination of its agricultural versatility, industrial applications, and environmental benefits makes B. carinata a promising candidate for addressing contemporary challenges in food security, sustainable agriculture, and renewable energy production. These multifaceted attributes have attracted the global attention for B. carinata as a potential crop for sustainable agriculture and alternative energy development [17].

Ethiopia has a diverse collection of over 400 B. carinata accessions, maintained at the Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute (EBI), along with released varieties at the Holeta Agricultural Research Center (HARC) [18, 19]. This rich germplasm pool provides significant opportunities for the development of superior cultivars with enhanced seed yield (SY), oil quality, and secondary metabolite content. However, a comprehensive understanding of the phenotypic variability within this collection remains limited, which impedes effective germplasm management and cultivar improvement. This knowledge gap underscores the need for comprehensive characterization of the available gene pool to fully exploit the potential of the crop in breeding programs aimed at developing new cultivars with enhanced SY and oil quality traits. Such characterization is crucial for identifying and selecting desirable traits, understanding genetic diversity, and guiding targeted breeding efforts to meet agricultural and industrial needs. Multiple approaches, including morphological, physiological, biochemical, and molecular marker techniques, have been reported for comprehensive diversity studies; however, morphophysiological diversity analysis remains the primary method for initial germplasm characterization [20].

The rich morphophysiological diversity in plants, including B. carinata, is the result of centuries of cultivation, selective breeding, and natural variation, and represents a valuable resource for crop improvement [21]. This approach provides a cost-effective and readily accessible means for assessing diversity, particularly in resource-limited settings. Moreover, morphophysiological traits are often directly related to agronomic performance and adaptability, making them valuable indicators for breeding programs. This characterization serves as a foundation for more advanced genetic studies and targeted improvements. Systematic evaluation of morphophysiological traits across the B. carinata germplasm collection can reveal patterns of variation, identify promising accessions, and inform strategic decisions in breeding programs.

Recent studies have successfully employed various analytical techniques to assess the agromorphological and physiological diversity of Brassica species, including classification and regression tree algorithms [22] and morphophysiological trait analyses [23]. Although previous studies have provided valuable insights into the morphological variation of B. carinata [1, 3, 6, 24, 25], they have been limited in scope, focusing primarily on a small number of accessions (36–64) and solely on morphological traits which do not provide a holistic picture of the genetic potential of B. carinata. Hence, a more comprehensive understanding of both morphological and physiological diversity in broader germplasm collections is necessary to unlock the full potential of this valuable crop. To address this knowledge gap, the present study was designed to systematically employ a combination of morphological and physiological diversity analysis techniques and evaluate 386 Ethiopian mustard accessions for both quantitative agromorphological and physiological traits. This comprehensive analysis aimed to determine the extent of phenotypic variation within the germplasm collection across multiple quantitative traits, identify promising genotypes with desirable traits for breeding, inform strategic conservation efforts, and lay the groundwork for developing improved cultivars tailored to diverse environments and applications. These findings are expected to provide a holistic picture of the genetic potential of B. carinata and contribute significantly to efficient germplasm management and exploitation, ultimately supporting sustainable agriculture and alternative energy development initiatives.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Experimental Site

The experiment was conducted during summer and autumn (June–December) main cropping seasons in 2022 and 2023 at the HARC, located in Holeta, Ethiopia. The site is representative of the central Ethiopian highlands and is situated at 9°06′ N and 38°31′ E, ~30 km west of Addis Ababa. It sits at an altitude of 2400 m above sea level, characterized by red-brown fertile soil with a pH range of 6.0–7.5, and an average annual rainfall of 1100 mm. The average maximum and minimum temperatures are 22 and 6°C, respectively [26].

2.2. Plant Materials

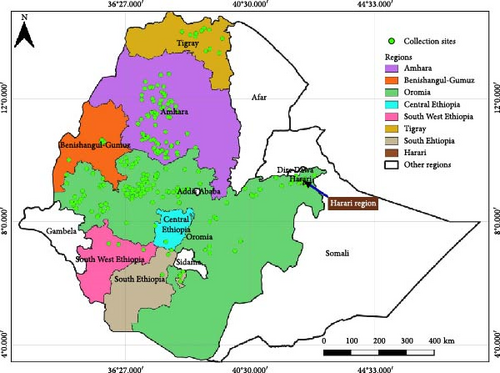

The experiment evaluated a total of 386 B. carinata genotypes collected from diverse growing regions across Ethiopia (Figure 1) between 1984 and 2022 by EBI and HARC. These genotypes included 339 accessions obtained from EBI, 36 accessions, and five released varieties (Derash, Holletta-1, S-67, Tesfa, and Yellow Dodolla) sourced from HARC and the remaining six accessions were collected by researchers. Passport data for the accessions are available in Supporting Information 1: Table S1.

2.3. Experimental Set-Up, Design, and Management

The experiment was laid out using an augmented block design (ABD) with two replicates per block. Four main blocks, each measuring 3.6 × 49.8 m, were established with 2 m pathways separating them. Each main block was divided into two sub-blocks, and two plots were established within each sub-block. To ensure unbiased evaluation, the positions of the accessions and check varieties were randomized. Individual accessions were randomly planted in 1.5 m long ridges. Check varieties were sown after every 10 accessions in a double ridge plot with a spacing of 10 × 30 cm, following HARC [19] guidelines. Seeds were hand drilled at a rate of 10 kg/ha, and fertilizers were applied at rates of 46 kg/ha N and 69 kg/ha P2O5. Standard agronomic practices were employed throughout the experiment, adhering to national B. carinata recommendations [19].

2.4. Data Collection

Data on 21 agromorphological and six physiological traits were collected from 10 randomly selected B. carinata plants per plot (midrow). Trait selection and measurement followed the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources guidelines for Brassica and Raphanus descriptors [27]. The agromorphological traits were recorded at various stages of the plant’s growth cycle including days to emergence (day days from seeding to 90% seedling emergence), petiole length (PL) (cm), number of leaves, leaf length (LL), leaf diameter, number of primary and secondary branches (NPB and NSB) per plant, days to flowering (days from sowing to 90% flower emergence), flower inflorescence length, days to harvest (days from sowing to harvest), plant height (m), diameter of stem, number and length (cm) of siliques per plant, number of seed per siliques, silique diameter, number of seed/plant, oil yield (OY), 1000-seed weight (g), SY (t/ha), and oil content (%). The oil content was analyzed using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMRS) equipment (Newport 4000, UK) following the protocols established by the Oregon State University Seed Laboratory (https://seedlab.oregonstate.edu/). Physiological data were collected in the morning during the vegetative stage of the plants, including the number of stomata per leaf surface area, width of stomata, stomatal conductance (SC) (mmol CO2 m−2 s−1), photosynthesis rate (µmol CO2 m−2 s−1), transpiration rate (mL), and chlorophyll fluorescence (FU). Detail information about trait types, their corresponding codes, measurement time, and methods, along with their respective units of measurement are provided in Supporting Information 1: Table S2.

2.5. Data Analysis

Prior to analysis, the data were checked using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) 9.4 [28] to ensure that the analysis of variance (ANOVA) assumptions were met. The 2-year morphophysiological data were then combined and analyzed using the same package with a significance level of α = 0.05. For multivariate ANOVA, the combined means were standardized (mean = 0, variance = 1) via R 4.3.2 [29] to address potential data scale discrepancies. Multivariate principal component analysis (MPCA) and cluster analysis were conducted using the FactoMineR package [30] in R to identify key traits and patterns. Correlation analysis was performed via the corrplot package in R to assess the strength and direction of relationships between traits. The unweighted pair group method with arithmetic (UPGMA) mean with agglomerative hierarchical clustering based on Euclidean distances was employed, as described by Lance and Williams [31]. Euclidean distances were calculated via the Factoextra package R [32] to determine genetic distances between accessions, as described by Gan, Li, and Li [33].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. ANOVA

3.1.1. Morphophysiological Traits Variability Based on Univariate Statistics

ANOVA conducted on averaged seasonal data indicated that the year had no significant (p > 0.05) effects on any agromorphological or physiological traits. Consequently, data from both seasons were combined for further analysis. The combined ANOVA results revealed highly significant (p ≤ 0.001) differences across all 27 morphophysiological traits examined (Table 1), highlighting the existence of rich phenotypic diversity within the B. carinata germplasm. This diversity is crucial for breeding programs aimed at developing cultivars with improved yields, oil content, disease resistance, and adaptability to various environmental conditions. The observed genetic richness not only offers immediate breeding opportunities but also represents a valuable resource for long-term crop improvement and adaptation to future challenges. These results are consistent with those of [1, 25, 34] who reported significant variations in the agromorphological traits of characterized B. carinata accessions. However, the current study’s larger sample size and broader range of examined traits provide a more comprehensive picture of species diversity.

Univariate analysis revealed highly significant (p ≤ 0.001) variations in most of the agromorphological and physiological traits (Table 1), indicating the diverse genetic makeup of the B. carinata accessions studied. However, traits such as the number of siliques, silique diameter, oil content, stomatal number, and width exhibited minimal variation due to both replication and season (p > 0.05). This minimal variation suggests the effectiveness of blocking design in mitigating seasonal and field-related effects. The successful minimization of environmental influences through proper experimental design provides reliable data for breeders to identify superior genotypes. Traits that are less susceptible to environmental influences are typically more heritable and predictable in breeding programs. These results highlight the reduced environmental influence on the collected data, enhancing their reliability in representing the accession performance. Conversely, traits such as days to harvest, plant height, number of seeds per silique, number of seeds per plant, SY, OY, photosynthesis rate, and SC showed nonsignificant (p > 0.05) variation within replicates due to blocking, further confirming the importance of blocking in reducing field variability. These findings are consistent with those of previous reports on B. juncea [23] and sugarcane [35] which documented reduced within-study variation attributed to unpredictable environmental and climatic factors. The observed patterns of trait variation provide valuable insights into breeding programs for B. carinata. Traits exhibiting high heritability and low environmental influences, such as silique characteristics and oil content, may be more suitable targets for direct selection. In contrast, traits showing greater environmental sensitivity, such as SY and physiological parameters, may require more complex selection strategies or multienvironmental trials to ensure stable performance across diverse conditions.

This study also revealed strong correlations between the analyzed traits and B. carinata performance, with coefficients of determination (R2) reaching up to 99.8% for chlorophyll FU (Table 1). Even the lowest observed R2 value of 68.65% for days to flowering demonstrated substantial explanatory power. These high R2 values suggest that the selected traits effectively capture the variation within the B. carinata population, providing breeders with reliable indicators for selecting desired characteristics. The results align with the findings of Montgomery [36] who reported that high R2 values (approaching 100%) indicate robust variability within a population. Additionally, all measured traits exhibited coefficients of variations (CVs) below the established critical threshold of 30% (Table 1), suggesting effective control of experimental variability. Notably, the minimum CV observed was a mere 2.61%, further emphasizing the limited influence of uncontrolled factors on the experimental outcomes. These consistently low CV values across all traits underscore the reliability and reproducibility of the data, providing a solid foundation for informed breeding decisions. These results support those of Gomez and Gomez [37] who reported that CVs below 30% are acceptable for agricultural field experiments. In general, the combination of high R2 values and low CVs observed in this study highlights the robustness of the experimental design and the significance of the selected traits in characterizing B. carinata accessions. These results not only validate the choice of traits for evaluation but also provide valuable insights into the genetic diversity present within the studied population. Such information is crucial for developing targeted breeding strategies aimed at improving yield, oil content, and other agronomically important traits in B. carinata.

3.1.2. Morphophysiological Traits Variation Based on Range and Mean Values

Analysis of the B. carinata accessions revealed substantial variation in both means and ranges across a diverse array of agromorphological and physiological traits (Table 1). This extensive phenotypic diversity revealed rich genetic potential within the evaluated germplasm collection. Notably, SY, a critical agronomic trait, demonstrated remarkable variation, ranging from 11.75 to 12.40 t/ha, with a mean yield of 12.08 t/ha. This high average yield suggests the presence of promising lines within the germplasm collection, offering significant potential for breeding cultivars with enhanced seed-production capabilities. The study also revealed considerable variation in six key traits: OY (mean: 2.71 t/ha; range: 2.65–2.77 t/ha), days to harvest (mean: 168.94 days; range: 165.52–172.36 days), days to flowering (mean: 117.07 days; range: 81.0–140.0 days), number of seeds per silique (mean: 750.9; range: 70.2–3460), oil content (mean: 43.28%; range: 37.88%–46.98%), and silique number per plant (mean: 99.99; range: 15.1–546.1). The extensive range observed in days to flowering and harvest is particularly noteworthy as it indicates the potential to develop varieties suited to diverse planting windows and adaptable to varying environmental conditions. This flexibility in phenology could prove invaluable in breeding cultivars that are resilient to climate variability and are suitable for different agricultural systems. The substantial variation in seed number per silique and silique number per plant suggests opportunities for increasing the overall SY through targeted breeding efforts. Similarly, the range in oil content (37.88%–46.98%) presents an opportunity to develop superior varieties with improved OY per hectare. This rich agromorphological diversity within the germplasm collection represents a valuable resource for B. carinata improvement. It provides breeders with a robust foundation for targeted enhancements in seed and OYs, earlier flowering and maturation times, increased seed and silique production, and the development of cultivars with enhanced environmental adaptability. These findings align with previous reports on B. carinata [21, 38, 39] and related species, such as B. juncea [23] which have documented similar variations in flowering time, maturity, SY, oil content, and OY.

Furthermore, the analysis revealed significant phenotypic variations across a wide spectrum of agromorphological traits (Table 1). This extensive diversity suggests rich genetic potential within the evaluated germplasm collection, presenting valuable opportunities for targeted crop improvement. Notably, several key traits exhibited particularly wide ranges and substantial mean values, including number of secondary branches (range: 3.15–26.50, mean: 10.89), days to seedling emergence (range: 3.5–18 days, mean: 10.87 days), seed number per silique (range: 3.54–13.22, mean: 7.41), silique length (range: 3.19–8.91 cm, mean: 5.25 cm), 1000-seed weight (range: 2.44–6.05 g, mean: 4.05 g), leaf number (range: 2.40–37.40, mean: 15.21), and LL (range: 2.3–11.78 cm, mean: 7.23 cm). This remarkable variation in agronomically important traits highlights the potential of this collection as a valuable resource for selecting superior parental lines in breeding programs. For instance, the diversity observed in branching patterns could be exploited to develop cultivars with enhanced canopy architecture, potentially improving light interception and yield. Similarly, the variation in silique characteristics (length and seed number) and seed weight presents opportunities for increasing overall SY and quality. The observed phenotypic diversity suggests a wealth of genetic variability within the germplasm that can be leveraged for various breeding objectives. For example, the wide range of days to seedling emergence (3.5–18 days) could be utilized to develop varieties with improved early vigor or adaptability to different planting conditions. The substantial variation in leaf characteristics (number and length) may contribute to the development of cultivars with optimized photosynthetic capacities and stress tolerances. Furthermore, the diversity in 1000-seed weight (2.44–6.05 g) indicates the potential for breeding programs aimed at improving seed size and quality, which are crucial factors for market acceptance and processing efficiency. The considerable variation in silique traits, both in terms of length (3.19–8.91 cm) and seed number per silique (3.54–13.22), presents opportunities for enhancing reproductive efficiency and overall yield potential. Collectively, these findings emphasize the importance of this germplasm collection as a genetic reservoir for B. carinata improvement programs. The wide diversity observed across multiple traits provides plant breeders with a robust foundation for developing cultivars tailored to specific agronomic needs, environmental conditions, and market demands. The results align with previous reports on B. carinata [25, 38, 40] and other Brassica species [23, 41] which have documented extensive variation in morphological and agronomic traits.

In addition, this study revealed significant (p ≤ 0.05) variation in physiological traits among B carinata accessions as well (Table 1), highlighting the rich diversity within the evaluated germplasm. This physiological plasticity presents valuable opportunities for targeted crop improvement and adaptation to diverse environmental conditions. Key findings include stomatal characteristics (number of stomata: range 153.8–297.8, mean 227.56; stomatal width: range 5.40–60.5 μm, mean 21.39 μm; SC: range 118.0–399.7 mmol m⁻2 s⁻1, mean 283.8 mmol m⁻2 s⁻1), gas exchange parameters (photosynthesis rate: range 4.62–34.87 μmol m⁻2 s⁻1, mean 15.52 μmol m⁻2 s⁻1; transpiration rate: range 2.54–15.4 mmol m⁻2 s⁻1, mean 7.42 mmol m⁻2 s⁻1), photosynthetic efficiency: chlorophyll FU (Fv/Fm): range 0.86–0.92, mean 0.89 (Table 1). The extensive variation in stomatal characteristics, particularly the number (153.8–297.8) and conductance (118.0–399.7 mmol m⁻2 s⁻1), suggests significant diversity in water use efficiency and gas exchange capacity among accessions. This variation could be instrumental in developing cultivars adapted to different moisture regimes or with improved drought tolerance. The wide range observed in photosynthesis rates (4.62–34.87 μmol m⁻2 s⁻1) indicates substantial differences in carbon assimilation capacity among accessions. This diversity presents opportunities for selecting high-performing genotypes with enhanced biomass production and potentially higher yield potential. Chlorophyll FU values (Fv/Fm) ranging from 0.86 to 0.92 suggest overall good photosynthetic efficiency across the accessions, with potential for selecting genotypes with superior light utilization capacity.

This physiological diversity provides a robust foundation for breeding programs aimed at developing B. carinata cultivars with enhanced environmental adaptability and stress tolerance. Breeders can leverage this variation to select genotypes exhibiting superior physiological traits such as efficient gas exchange, optimal stomatal function, and increased photosynthetic efficiency. These selections can contribute to the development of cultivars better adapted to challenging environments, thus promoting sustainable agriculture in the face of climate variability. The results align with earlier studies on related Brassica species, including oilseed Brassicas [42], canola [43], and cabbage [44], which all consistently reported substantial variation in similar physiological traits.

3.1.3. Genotypes With Mean Performance Exceeding the Population Mean

The analysis of 386 B. carinata genotypes revealed substantial phenotypic diversity, with a significant proportion of accessions (27.9%–80.6%) surpasses the population mean values for various morphophysiological traits (Table 1). This extensive variation underscores the rich genetic potential within the evaluated accessions. Key findings include vegetative traits: leaf number: 75.59% (293 genotypes) exceeded the mean, leaf width (LW): 51.55% (199 genotypes) surpassed the mean, and secondary branches: 40.67% (157 genotypes) showed above-average values and plant height: 50.26% (194 genotypes) were taller than the mean. Among the reproductive traits: silique number: 36.01% (139 genotypes) exceeded the mean, seeds per silique: 41.45% (160 genotypes) surpassed the average, silique length: 36.27% (140 genotypes) were above the mean, and 1000-seed weight: 43.78% (169 genotypes) showed higher than average values. From yield components such as oil content: 27.98% (108 genotypes) exceeded the mean, SY: 49.74% (192 genotypes) surpassed the average.

Likewise, physiological traits: stomatal number: 77.98% (301 genotypes) showed above-average values, photosynthetic rate: 47.15% (182 genotypes) exceeded the mean, transpiration rate: 31.09% (120 genotypes) surpassed the average, SC: 80.57% (311 genotypes) were above the mean, and chlorophyll FU: 39.12% (151 genotypes) showed higher than population average values (Table 1). This extensive variation within the germplasm collection highlights its rich morphophysiological diversity, presenting a valuable resource for breeding programs. The observed diversity allows for the strategic combination of favorable traits in cultivar improvement efforts. For instance, genotypes exhibiting superior values for both yield components (e.g., silique number, seeds per silique) and physiological traits (e.g., photosynthetic rate, SC) could be selected as potential parents for developing high-yielding, stress-tolerant cultivars. The findings are consistent with previous reports on B. carinata [45] and related species such as B. juncea [41] consistently documented high mean values exceeding population averages for traits including plant height, SY, and oil content.

| Traits | Accession (385) | Sub-block (37) |

Replication (1) | Season (1) |

R2 (%) |

CV (%) | Range (min–max) |

Mean ± SE | # accession, > μ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days to emergence (day) | 18.104 ∗∗∗ | 1.173ns | 0.764 ∗∗∗ | 67.34 ∗∗ | 89.98 | 27.68 | 3.5–18 | 10.87 ± 0.15 | 308 |

| Petiole length (cm) | 18.104 ∗∗∗ | 1.173ns | 0.764 ∗∗∗ | 67.34 ∗∗ | 89.98 | 27.68 | 3.5–18 | 10.87 + 0.15 | 128 |

| Number of leaves (#) | 5.226 ∗∗∗ | 0.004ns | 3.526 ∗∗∗ | 1.051 ∗∗ | 93.95 | 27.15 | 1.09–10.57 | 5.95 + 0.08 | 293 |

| Leaf length (cm) | 55.883 ∗∗∗ | 3.603ns | 1.387 ∗∗∗ | 1.424 ∗∗ | 96.54 | 24.76 | 2.40–37.40 | 15.21 + 0.27 | 152 |

| Leaf width (cm) | 4.282 ∗∗∗ | 0.003ns | 3.171 ∗∗∗ | 0.535 ∗∗ | 98.88 | 20.25 | 2.3–11.78 | 7.23 + 0.07 | 199 |

| Number of primary branch (#) | 2.939 ∗∗∗ | 0.005ns | 3.235 ∗∗∗ | 3.538 ∗∗ | 92.86 | 24.34 | 1.40–8.75 | 4.98 + 0.06 | 301 |

| Number of secondary branch (#) | 11.644 ∗∗∗ | 0.007ns | 0.112 ∗∗∗ | 6.715 ∗∗∗ | 97.89 | 23.91 | 4.75–25.00 | 10.09 + 0.12 | 157 |

| Days to flower (day) | 35.416 ∗∗∗ | 0.008ns | 5.963 ∗∗∗ | 3.847 ∗∗∗ | 95.64 | 18.63 | 3.15–26.50 | 10.89 + 0.21 | 258 |

| Flower inflorescence (cm) | 251.15 ∗∗∗ | 1.5n49ns | 1.553 ∗∗∗ | 7.286 ∗∗∗ | 99.8 | 9.57 | 81.0–140.0 | 117.07 + 0.57 | 128 |

| Days to harvest (day) | 0.131 ∗∗∗ | 0.015ns | 0.186ns | 0.006ns | 90.55 | 8.56 | 0.57–1.92 | 1.38 + 0.01 | 220 |

| Plant height (m) | 541.85 ∗∗∗ | 77.698 ∗∗∗ | 68.35 ∗∗∗ | 690.28 ∗ | 88.20 | 5.08 | 102.5–196 | 168.94 + 0.84 | 194 |

| Diameter of stem (cm) | 0.125 ∗∗∗ | 0.002 ∗∗∗ | 1.82 ∗∗∗ | 0.004 ∗∗ | 99.44 | 2.61 | 0.72–2.15 | 1.64 + 0.01 | 198 |

| Silique number (#) | 1.866 ∗∗∗ | 0.108ns | 1.244 ∗∗∗ | 0.005 ∗∗∗ | 96.65 | 7.48 | 0.89–5.75 | 3.44 + 0.05 | 139 |

| Silique length (cm) | 3569.5 ∗∗∗ | 104.94ns | 747 ns | 129.7ns | 81.99 | 28.96 | 15.1–546.1 | 99.99 + 2.15 | 160 |

| Silique diameter (mm) | 2.406 ∗∗∗ | 0.169ns | 1.689 ∗∗∗ | 0.653 ∗∗ | 94.54 | 7.16 | 3.19–8.91 | 5.25 + 0.06 | 148 |

| Number of seed/silique (#) | 0.346 ∗∗∗ | 0.004ns | 4.01ns | 0.06ns | 97.75 | 8.65 | 0.76–3.46 | 2.36 + 0.02 | 194 |

| Number of seed/plant (#) | 9.225 ∗∗∗ | 0.07 ∗∗∗ | 0.07 ∗∗∗ | 0.06 ∗∗∗ | 99.28 | 27.00 | 3.54–13.22 | 7.41 + 0.11 | 139 |

| 1000-seeds weight (g) | 304,527 ∗∗∗ | 429.5 ∗∗∗ | 377.41 ∗∗ | 4220 ∗∗ | 98.17 | 4.96 | 70.2–3,460 | 750.9 + 19.9 | 169 |

| Seed yield (t/ha) | 1.46 ∗∗∗ | 0.003ns | 0.05 ∗∗∗ | 0.10 ∗∗∗ | 87.64 | 21.07 | 2.44–6.05 | 4.05 + 0.04 | 192 |

| Oil content (%) | 1101.86 ∗∗∗ | 0.03 ∗∗∗ | 0.03 ∗∗∗ | 0.08 ∗∗∗ | 78.42 | 14.97 | 2.65–2.69 | 2.71 + 0.01 | 108 |

| Oil yield (t/ha) | 11.10 ∗∗∗ | 0.40ns | 74.07ns | 26.11ns | 96.79 | 5.44 | 37.88–46.98 | 43.28 + 0.12 | 192 |

| Number of stomata (#) | 3890.86 ∗∗∗ | 16.11 ∗∗∗ | 15.49 ∗∗∗ | 104.4 ∗∗ | 94.82 | 16.24 | 11.75–12.40 | 12.08 + 0.62 | 301 |

| Width of stomata (μm) | 1674.8 ∗∗∗ | 698.6ns | 695.2ns | 260.4ns | 71.75 | 3.02 | 153.8–297.8 | 227.56 + 1.47 | 168 |

| Photosynthesis rate (μmol m−2 s−1) | 219.5 ∗∗∗ | 238.3ns | 175.7ns | 126.2ns | 81.03 | 28.53 | 5.40–60.5 | 21.39 + 0.53 | 182 |

| Transpiration rate (mL s−1) | 55.19 ∗∗∗ | 5.54 ∗∗∗ | 13.97 ∗∗∗ | 131.9 ∗∗ | 98.99 | 15.16 | 4.62–34.87 | 15.52 + 0.27 | 120 |

| Stomatal conductance (mmol m−2 s−1) | 9.04 ∗∗∗ | 3.14ns | 2.241 ∗∗∗ | 870.2 ∗∗ | 81.24 | 22.91 | 2.54–15.4 | 7.42 + 0.11 | 311 |

| Chlorophyll fluorescence (FU) | 0.015 ∗∗∗ | 0.011ns | 1.215ns | 3.219 ∗∗ | 68.65 | 6.86 | 0.86–0.92 | 0.78 ± 0.00 | 151 |

- Note: The numbers within the braces in the title bar represent the degrees of freedom of the corresponding sources of variation.

- Abbreviations: >, greater than symbol; μ, population mean; CV, coefficients of variation; FU, fluorescence unit; HARC, Holeta Agricultural Research Center; R2, coefficient of determination; SE, standard error; , accessions mean.

- ∗, ∗∗, ∗∗∗, and nsIndicates significant at p ≤ 0.05, p ≤ 0.01, p ≤ 0.001, and nonsignificant at p > 0.05, respectively

3.1.4. Comparison of Means of Accessions to Checks

Compared with the checks, the B. carinata accessions presented superior performance across several traits, including faster germination; increased vegetative development (evidenced by increased leaf number, branching, stem thickness, and plant height); greater SY and oil content/yield; wider stomata; elevated photosynthetic rates; and improved chlorophyll FU (Table 2). This extensive phenotypic variation presents breeders with an opportunity to leverage the germplasm collection for targeted selection of parental lines. By combining desired traits, such as high-yield and oil-rich genotypes with improved plant architecture and maturity characteristics, breeders can develop superior cultivars. These findings are in direct agreement with previous reports [25, 41, 42] which documented significant variation in branch number, seed/OY, and content among B. carinata genotypes.

3.1.5. Comparison of Means of the Top 5% Genotypes With Population and Checks

Analysis of the top 5% (19 genotypes) revealed superior mean performance for most traits, with the exception of LL and LW, stem diameter, 1000-seed weight, number of stomata, and transpiration rate, when compared to both the population mean and check varieties (Table 2). Notably, when selecting genotypes based on SY, oil content, and OY, significant increases were observed compared to both the population mean and the check. Specifically accessions: acc-192, acc-194, acc-377, acc-1, acc-386, acc-247, acc-235, acc-294, acc-302, acc-112, acc-331, acc-152, acc-55, and acc-72 demonstrated SY increases ranging from 16.70% to 44.30%. Similarly, acc-386, acc-1, acc-21, acc-383, acc-192, acc-31, acc-12, acc-381, acc-193, acc-378, acc-331, acc-235, acc-302, acc-375, acc-72, acc-124, and acc-152 showed oil content increases between 27.4% and 58.7%, while acc-192, acc-194, acc-1, acc-193, acc-386, acc-152, acc-377, acc-331, acc-299, acc-126, acc-281, acc-43, acc-328, acc-72, acc-77, and acc-17 exhibited OY increases ranging from 22.6% to 35.8% (Table 2). Furthermore, when selecting genotypes based on critical agromorphological traits such as leaf number, length, and diameter, plant height, days to flowering and harvest, SY, oil content, and OY, accessions: acc-301, acc-192, acc-1, acc-193, acc-311, acc-386, acc-173, acc-381, acc-331, acc-131, acc-194, and acc-108 exhibited top performance (Table 2). This suggests that these elite genotypes hold significant potential as parents for breeding programs aimed at developing high-yielding, stress-tolerant cultivars tailored for diverse end uses. These elite genotypes also represent a valuable resource for further characterization and prioritization to create offspring with maximized genetic variation, crucial for successful marker-assisted selection (MAS) and genomic selection (GS) programs. These findings are in line with previous reports on B. carinata [46] and B. juncea [47] which also identified superior genotypes.

| Traits | of accessions | of checks | Difference | T-value | p-Value | High-performing genotypes (n = 19) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days to emergence (day) | 10.865 | 8.08 | 2.785 | 0.064 | 0.012 | 301, 281, 311, 21, 381,51, 331, 271, 131, 351, 291, 371, 171, 141, 341, 321, 211, 221, 31 |

| Petiole length (cm) | 6.909 | 5.942 | 0.967 | 0.831 | 0.026 | |

| Number of leaves (#) | 21.171 | 15.1 | 6.071 | 0.533 | 0.011 | |

| Leaf length (cm) | 7.216 | 8.09 | −0.874 | 0.966 | 0.087 | |

| Leaf width (cm) | 4.972 | 5.687 | −0.715 | 0.972 | 0.175 | |

| Number of primary branch (#) | 10.074 | 8.3 | 1.774 | 0.986 | 0.02 | |

| Number of secondary branch (#) | 11.5 | 8.864 | 2.636 | 0.174 | 0.032 | |

| Days to flower (day) | 108.04 | 100.6 | 7.44 | 0.822 | 0.001 | 301, 281, 311, 21, 381, 51, 331, 131, 271, 351, 291, 371 |

| Flower inflorescence (cm) | 1.377 | 1.181 | 0.196 | 0.084 | 0.018 | 331, 131, 21, 381, 35, 281, 11, 171, 141, 136, 121, 31 |

| Days to harvest (day) | 165.9 | 150.8 | 15.1 | 0.095 | 0.001 | 220, 88, 217, 224, 244, 353, 245, 286, 18, 22, 66, 166 |

| Plant height (m) | 2.142 | 1.639 | 0.503 | 0.124 | 0.017 | 21, 381, 51, 131, 331, 271, 311, 281, 171, 291, 371, 351 |

| Diameter of stem (cm) | 3.939 | 3.902 | 0.037 | 0.662 | 0.051 | 261, 271, 68, 264, 262, 3, 96, 1, 91, 134, 147, 115, 140 |

| Silique number (#) | 108.3 | 106.75 | 1.55 | 0.720 | 0.011 | 239, 21, 311, 51, 331, 271, 301, 131, 281, 351, 291, 371 |

| Silique length (cm) | 5.238 | 6.328 | −1.09 | 0.804 | 0.003 | 5, 13, 27, 10, 33, 21, 46, 193, 167, 173, 171, 250, 282 |

| Silique diameter (mm) | 2.354 | 2.508 | −0.154 | 0.578 | 0.438 | 126, 162, 362, 138, 244, 237, 319, 133, 128, 206, 213, 84 |

| Number of seed/silique (#) | 7.403 | 7.65 | −0.247 | 0.996 | 0.059 | 111, 61, 1, 81, 101, 215, 106, 136, 54, 145, 224, 107, 234 |

| Number of seed/plant (#) | 936 | 928.5 | 7.5 | 0.970 | 0.002 | 239, 21, 311, 51, 331, 271, 301, 131, 281, 351, 291, 371 |

| 1000-seeds weight (g) | 4.056 | 4.064 | −0.008 | 0.964 | 0.391 | 369, 45, 23, 35, 60, 292, 204, 322, 13, 305, 38, 49, 5, 355 |

| Seed yield (t/ha) | 2.738 | 2.652 | 0.086 | 0.807 | 0.038 | 192, 194, 377, 193, 1,386, 247, 235, 294, 302, 112, 331,152, 55, 72 |

| Oil content (%) | 46.835 | 46.822 | 0.013 | 0.156 | 0.023 | 386, 1, 21, 383, 31, 12, 381, 193, 378, 331, 235, 302, 375, 72, 124, 152 |

| Oil yield (t/ha) | 13.252 | 12.955 | 0.297 | 0.816 | 0.030 | 192,194, 1, 193, 386, 152, 377, 331, 299, 126, 281, 43, 328, 72, 77, 17 |

| Number of stomata (#) | 237.34 | 244.6 | −7.26 | 0.109 | 0.099 | 301, 281, 311, 21, 381, 51, 331, 271, 131, 351, 291, 371, 171 |

| Width of stomata (μm) | 27.335 | 25.48 | 1.855 | 0.115 | 0.002 | 68, 288, 93, 214, 311, 287, 67, 97, 94, 286, 285, 325, 95 |

| Photosynthesis rate (μmol m−2 s−1) | 15.527 | 15.22 | 0.307 | 0.204 | 0.053 | 192, 124, 377, 112, 1, 386, 55, 331, 235, 302, 375, 72, 171, 98, 20 |

| Transpiration rate (mL s−1) | 7.405 | 8.152 | −0.747 | 0.693 | 0.545 | 120, 231, 112, 241, 42, 46, 345, 44, 190, 225, 183, 25, 188 |

| Stomatal conductance (mmol m−2 s−1) | 342.5 | 336.03 | 6.47 | 0.825 | 0.013 | 311, 281, 301, 291, 386, 321,192,171, 31, 331, 351, 21, 51 |

| Chlorophyll fluorescence (FU) | 0.785 | 0.757 | 0.028 | 0.509 | 0.003 | 112, 124, 181, 331, 55, 231, 101, 251, 221, 71, 384, 261, 191 |

- Abbreviations: >, greater than symbol; μ, population mean, FU, fluorescence unit; , accessions mean.

3.2. Multivariate Principal Component (PC) and Cluster Analysis

3.2.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA offers a dimensionality reduction technique for high-dimensional data. It transforms complex datasets into a smaller set of key PCs that capture the most significant variation and underlying patterns within the original data [48]. Eigenvalue analysis guides the selection of informative PCs to retain for further analysis [46]. Factor loadings associated with a particular PC quantify the influence of individual traits on that PC [42]. Traits with higher absolute factor loading values (closer to 1 or −1) exert a stronger influence on the PC [49]. Additionally, the sign of the factor loading (+/−) reflects whether a trait is positively or negatively correlated with the PC [41]. This information empowers breeders to prioritize traits on the basis of their contribution to PCs and develop targeted breeding strategies for efficient crop improvement.

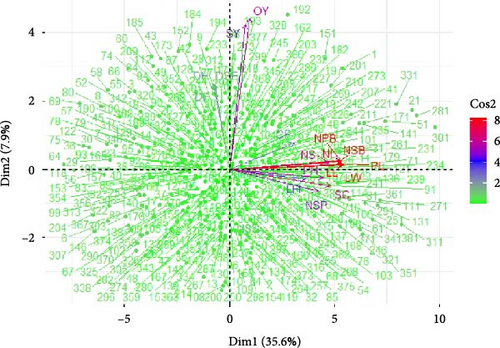

PCA of B. carinata accessions revealed distinct patterns of variation (Figure 2). The top 5 PCs, each with eigenvalues exceeding 1.341, collectively explained 61% of the total variance (Table 3). These findings deviate slightly from previous reports [50, 51] on B. carinata, where the top 5 PCs explained 68.2% and 70.8% of the total variation, respectively. This variation likely arises from differences in the experimental environments, accessions employed, and traits included in each study.

PCA revealed that the first PC (PC1) explained 35.59% of the variation observed among the B. carinata accessions (Table 3). Traits with high factor loadings exerted the strongest influence on PC1, include PL: 0.982, LW: 0.981, LL: 0.978, NPB and NSB: 0.965, SC: 0.871, silique number: 0.858, number of seeds per plant: 0.764, plant height: 0.808, flower inflorescence length: 0.658, chlorophyll FU: 0.564, and stomatal number: 0.348. These findings highlight the critical role that these traits play in morphophysiological variation within the B. carinata germplasm. Focusing on these traits during breeding programs has the potential to increase selection efficiency for targeted improvement. These results align with previous study on B. juncea [50] that PC1 explained 37.8% of the total variation, with PL, LW, and LL identified as the top contributing factors.

The second PC (PC2) accounted for 7.9% of the observed variation and grouped accessions primarily on the basis of SY (factor loading: 0.770) and OY (factor loading: 0.799) (Table 3). This pattern suggests that prioritizing these traits during breeding would be beneficial for developing cultivars with superior seed and OYs. These findings are consistent with previous reports on B. carinata [50–52] highlighted the importance of PC2 in explaining variation and its strong association with oil and SY traits.

The remaining PCs (PCs 3–5) explained additional variation and grouped accessions on the basis of specific trait combinations (Table 3). PC3 accounted for 6.82% of the variation and primarily reflected growth and development traits, with days to emergence (0.518), flowering (0.651), and harvest (0.591) exhibiting positive factor loadings, whereas oil content displayed a negative factor loading (−0.311). PC4 explained 5.91% of the variation and grouped accessions on the basis of silique characteristics (number: 0.654, width: −0.531, and length: 0.433) and photosynthetic efficiency (0.439). Finally, PC5 explained 4.97% of the variation, with 1000-seeds weight (−0.619), stem diameter (0.385), and transpiration rate (−0.311) contributed most significantly. By identifying these key traits associated with each PC group, breeders can strategically select parental lines during hybridization, allowing them to target desired traits for cultivar improvement. These findings are consistent with previous studies on B. carinata [45, 53] which reported associations between specific PCs and distinct sets of traits related to growth, yield, oil content, and other physiological processes.

| Traits | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days to emergence (day) | −0.124 | 0.449 | 0.518 | 0.263 | 0.089 |

| Petiole length (cm) | 0.982 | 0.027 | 0.081 | −0.067 | −0.004 |

| Number of leaves (#) | 0.965 | 0.042 | 0.076 | −0.132 | −0.049 |

| Leaf length (cm) | 0.978 | 0.020 | 0.081 | −0.059 | 0.014 |

| Leaf width (cm) | 0.981 | 0.024 | 0.079 | −0.061 | 0.002 |

| Number of primary branch (#) | 0.965 | 0.042 | 0.064 | −0.122 | −0.032 |

| Number of secondary branch (#) | 0.965 | 0.045 | 0.068 | −0.130 | −0.044 |

| Days to flower (day) | −0.134 | 0.438 | 0.651 | 0.055 | 0.112 |

| Flower inflorescence (cm) | 0.658 | −0.054 | 0.088 | 0.164 | 0.159 |

| Days to harvest (day) | −0.141 | 0.453 | 0.591 | 0.099 | 0.217 |

| Plant height (m) | 0.808 | −0.046 | 0.109 | 0.087 | 0.106 |

| Diameter of stem (cm) | 0.217 | −0.149 | −0.211 | 0.166 | 0.385 |

| Silique number (#) | 0.858 | 0.035 | 0.034 | −0.044 | −0.104 |

| Silique length (cm) | 0.132 | −0.129 | −0.141 | 0.433 | 0.398 |

| Silique diameter (mm) | 0.089 | −0.066 | 0.008 | −0.531 | 0.359 |

| Number of seed/silique (#) | 0.265 | −0.262 | −0.122 | 0.654 | −0.124 |

| Number of seed/plant (#) | 0.764 | −0.116 | −0.049 | 0.366 | −0.183 |

| 1000-seeds weight (g) | −0.242 | 0.070 | 0.063 | −0.135 | −0.619 |

| Seed yield (t/ha) | 0.137 | 0.770 | −0.484 | 0.004 | 0.098 |

| Oil content (%) | 0.131 | 0.250 | −0.311 | −0.036 | −0.072 |

| Oil yield (t/ha) | 0.174 | 0.799 | −0.551 | −0.013 | 0.071 |

| Number of stomata (#) | 0.348 | −0.072 | 0.026 | −0.185 | −0.019 |

| Width of stomata (μm) | −0.057 | −0.082 | 0.058 | −0.191 | 0.067 |

| Photosynthesis rate (μmol m−2 s−1) | −0.060 | 0.220 | −0.050 | 0.439 | −0.166 |

| Transpiration rate (mL s−1) | 0.071 | 0.137 | 0.112 | 0.230 | −0.311 |

| Stomatal conductance (mmol m−2 s−1) | 0.871 | −0.087 | −0.067 | 0.083 | 0.181 |

| Chlorophyll fluorescence (FU) | 0.564 | 0.141 | 0.032 | −0.117 | −0.414 |

| Eigenvalue | 9.610 | 2.144 | 1.842 | 1.596 | 1.341 |

| Individual (%) | 35.59 | 7.94 | 6.82 | 5.91 | 4.97 |

| Cumulative (%) | 35.59 | 43.53 | 50.36 | 56.26 | 61.23 |

- Note: PC1, PC2, PC3, and PC4, principal components 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

- Abbreviation: FU, fluorescence unit.

3.2.2. Relationships of Morphophysiological Traits and PCs

The PCA biplot visualization in Figure 2 depicts strong correlations between the analyzed morphophysiological traits in relation to the first two PCs: PC1 and PC2. Traits such as leaf size (PL, LW, and LL), branching (NPB and NSB), SC, silique number, plant height, number of seeds per plant, flower inflorescence length, and chlorophyll FU all presented high positive loadings on PC1. This pattern suggests that these traits are positively correlated and tend to covary. Similarly, SY, oil content, and days to maturity presented the highest positive loadings on PC2, indicating a strong correlation between them and their tendency to vary together. Understanding these intertrait relationships can inform selection strategies to avoid unintentionally impacting correlated traits during the selection process. These findings corroborate previous reports [53], on B. carinata, where traits with high loadings on different PCs were reported to indicate strong correlations and linked patterns of variability.

The PCA biplot (Figure 2) offers further insights on the basis of trait vector direction and length. Traits with vectors pointing in the same direction exhibit positive correlations. Notably, the coaligned vectors for PL and primary and secondary branch numbers all share positive correlations, indicating that they tend to increase or decrease together. Similarly, the same aligned SY and oil content vectors were positively correlated. Vector length, on the other hand, reflects a trait’s contribution to a particular PC. Longer vectors, such as the OY for PC2 and branch number for PC1, indicate a stronger influence on their respective PCs. Selection strategies can leverage these findings by targeting accessions with positive correlations for desired traits while considering the impact of highly influential traits (represented by long vectors) on overall variation. These observations are consistent with previous reports [45, 53] that documented coaligned trait vectors for leaf size, branching, SY, and oil content in B. carinata.

Overall, this study revealed that PL (PL: 0.982), LW (LW: 0.981), LL (LL: 0.978), the NPB and NSB (NPB = NSB = 0.965), SC (SC: 0.871), OY (OY: 0.799), and SY (SY: 0.770) were the most significant contributors to the phenotypic diversity observed among B. carinata genotypes. Therefore, genotypes exhibited superior mean values for these traits represent valuable targets for selection breeding.

The PCA biplot (Figure 2) again visualizes the extent of genetic variation among B. carinata accessions. The accessions positioned closer together and to the origin presented similar quantitative trait values, suggesting minimal genetic divergence. Conversely, accessions located far from the origin and each other represent more genetically divergent genotypes. Notably, accessions 1, 2, 15, 38, 58, 64, 69, 74, 80, 151, 152, 184, 192, 194, 204, 267, 301, 307, 311, 331, and 381 presented greater genetic divergence, making them promising candidates for crop improvement. These accessions can be directly selected for breeding programs or utilized as diverse parental lines in hybridization strategies to introduce valuable genetic variation and enhance breeding outcomes.

3.3. Cluster Analysis

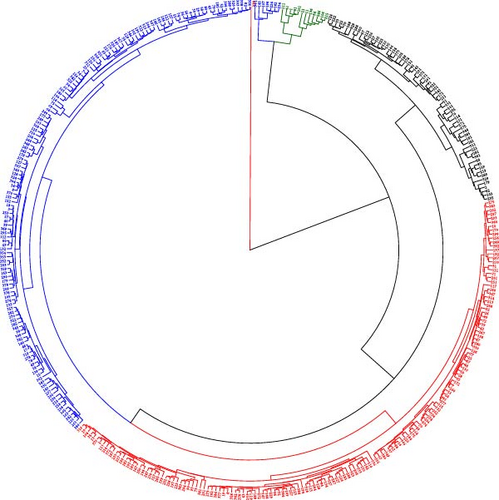

To classify the 386 B. carinata accessions based on genetic similarity, cluster analysis was performed using the UPGMA algorithm and Euclidean distance matrices. UPGMA prioritizes minimizing variation within clusters, making it ideal for identifying groups with high intracluster and low intercluster similarity [42]. Cluster analysis, using 27 morphophysiological traits, revealed four distinct diversity clusters (Figure 3). Cluster 1 (C1) comprised 153 accessions (39.64%) from various Ethiopian regions, while Cluster 2 (C2) was the largest with 157 accessions (40.67%) with Oromia (83), Amhara (49), Tigray (8), Benishangul-Gumuz (5), South Ethiopia (5), Southwest Ethiopia (4), Central Ethiopia (2), and Harari (1). Clusters C3 and C4 consisted of 12 and 64 genotypes, respectively, representing almost all the B. carinata growing regions (Figure 3, Table 4). This distribution of accessions suggests that genetic diversity is independent of geographic origin and likely reflects inter-regional germplasm exchange, common ancestral origin, or both. The presence of accessions from the same region within different clusters highlights morphophysiological diversity, probably arising from genetic variation due to ancestral differences or recombination events during hybridization. These findings align with those of previous studies on B. carinata [53] and sorghum [54], which stated that genetic factors play a more significant role in determining diversity than geographical location of the crop germplasm.

3.3.1. Estimation of Intra- and Inter-Cluster Distance

Cluster analysis revealed significant genetic distances (8.84–18.21) among the B. carinata accessions (Table 4). The greatest divergence was observed between clusters C3–C4 (18.21) and C2–C4 (14.44), suggesting substantial morphophysiological trait variation. This diversity indicates considerable potential for exploiting heterosis through breeding crosses between these genetically distinct clusters. Conversely, smaller genetic distances between clusters C1–C2 (8.84) suggest limited variation and potentially lower success rates for intragroup crosses. These results are consistent with those of previous reports on B. carinata [55] and B. juncea [22] which highlight the value of utilizing accessions with high genetic distances in breeding programs to maximize heterosis.

Further analysis of intracluster diversity revealed that C2 exhibited the greatest intracluster distance (6.71) and mean genetic distance (5.23) (Table 4). This pattern suggests a more diverse genetic composition within C2, implying that breeders can strategically select diverse parental lines from this cluster to broaden the genetic basis of the cultivars. These findings are consistent with previous reports on B. carinata [47] and sesame [56], in which clusters with varying levels of intracluster diversity have been reported.

| Cluster | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | Mean distance | Number of accessions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 6.542 | — | — | — | 4.915 | 153 |

| C2 | 8.844 | 6.714 | — | — | 5.234 | 157 |

| C3 | 14.265 | 9.592 | 5.974 | — | 2.821 | 12 |

| C4 | 12.997 | 14.443 | 18.213 | 6.396 | 3.746 | 64 |

- Note: C1, C2, C3, and C4, clusters 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

3.3.2. Analysis of Cluster Means

Cluster mean analysis revealed distinct agromorphological and physiological trait profiles within the B. carinata germplasm (Table 5). C1 accessions exhibited earlier flowering (114.61 days) with high stomatal density (233.33) and conductance (348.02 mmol m⁻2 s⁻1), traits potentially favorable for water management strategies. C2 accessions demonstrated rapid emergence (10.19 days), earlier maturity (159.69 days), and superior vegetative growth, characterized by longer petioles (8.07 cm) and leaves (9.34 cm), wider leaves (6.5 cm), taller plants (1.84 m), thicker stems (3.8 cm), and longer inflorescences (1.56 m). Additionally, C2 accessions showed greater numbers of leaves (22.31), primary branches (13.05), secondary branches (16.58), and siliques (188.85), as well as superior yield-related traits including more seeds per plant (2002.23), higher SY (1.75 t/ha), increased oil content (44.88%), and greater OY (0.78 t/ha). C2 accessions also exhibited enhanced photosynthetic activity, with the highest rates of photosynthesis (18.73 µmol m−2 s−1), transpiration (7.83 mL s−1), and chlorophyll FU (0.89 FU). These findings suggest that C2 accessions represent a valuable resource for breeding strategies aimed at improving seed and OY, environmental adaptation, and photosynthetic efficiency.

In contrast, C3 and C4 exhibited lower values for most traits but showed the highest values for 1000-seed weight (4.30 g), silique length (5.36 cm), and silique diameter (2.38 mm) (Table 5), indicating their potential utility in breeding programs targeting these specific traits. These results align with previous B. carinata studies reporting significant variation in trait distribution among clusters, including research on germination, maturity, and vegetative growth [45], early flowering and stomatal traits [53], and SY and oil content [52].

| Traits | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days to emergence (day) | 10.895 | 10.192 | 11.086 | 10.744 |

| Petiole length (cm) | 7.633 | 8.067 | 4.572 | 6.219 |

| Number of leaves (#) | 20.99 | 22.308 | 11.136 | 15.589 |

| Leaf length (cm) | 8.719 | 9.037 | 5.954 | 7.501 |

| Leaf width (cm) | 6.232 | 6.496 | 3.927 | 5.202 |

| Number of primary branch (#) | 12.66 | 13.050 | 8.147 | 10.378 |

| Number of secondary branch (#) | 15.557 | 16.581 | 7.594 | 11.216 |

| Days to flower (day) | 114.612 | 117.231 | 119.216 | 116.340 |

| Flower inflorescence (cm) | 1.502 | 1.563 | 1.221 | 1.445 |

| Days to harvest (day) | 168.037 | 159.692 | 171.392 | 168.076 |

| Plant height (m) | 1.804 | 1.864 | 1.455 | 1.699 |

| Diameter of stem (cm) | 3.547 | 3.838 | 3.337 | 3.458 |

| Silique number (#) | 137.201 | 188.850 | 70.237 | 101.955 |

| Silique length (cm) | 5.34 | 5.305 | 5.060 | 5.364 |

| Silique diameter (mm) | 2.335 | 2.123 | 2.359 | 2.380 |

| Number of seed/silique (#) | 9.094 | 11.534 | 5.745 | 7.730 |

| Number of seed/plant (#) | 1194.226 | 2002.226 | 397.039 | 759.387 |

| 1000-seeds weight (g) | 3.877 | 4.002 | 4.303 | 3.925 |

| Seed yield (t/ha) | 1.744 | 1.754 | 1.718 | 1.706 |

| Oil content (%) | 43.464 | 44.876 | 43.130 | 43.213 |

| Oil yield (t/ha) | 75.755 | 78.829 | 74.163 | 76.081 |

| Number of stomata (#) | 236.332 | 233.778 | 218.736 | 230.558 |

| Width of stomata (μm) | 21.774 | 19.073 | 21.770 | 21.116 |

| Photosynthesis rate (μmol m−2 s−1) | 14.887 | 18.728 | 15.456 | 15.580 |

| Transpiration rate (mL s−1) | 7.892 | 7.826 | 7.226 | 7.344 |

| Stomatal conductance (mmol m−2 s−1) | 348.023 | 373.856 | 222.309 | 299.890 |

| Chlorophyll fluorescence (FU) | 0.858 | 0.889 | 0.756 | 0.772 |

- Abbreviation: FU, fluorescence unit.

4. Conclusion and Prospects

This study revealed significant phenotypic variation across 27 agromorphological and physiological traits of Ethiopian mustard accessions. Diversity was evident through a wide range of trait means, PCA, and cluster analysis. Notably, 19 elite genotypes demonstrated substantial increases in SY (16.70%–44.30%) and oil content (27.4%–58.7%) compared with both the population mean and checks. PCA identified five PCs explaining over 61% of the variation, with leaf size, branching, SY, and OY contributing the most significantly. Cluster analysis revealed four groups with substantial genetic distances (8.84–18.21) between accessions, with the highest divergence occurring between C3 and C4. C2 exhibited the highest intracluster distance (6.71) and mean genetic distance (5.23), suggesting valuable morphophysiological variation in breeding programs.

- •

Group 1 (acc-192, acc-386, acc-1, acc-235, acc-294, acc-302, acc-112, acc-331, acc-152, acc-55, and acc-72) demonstrated significant potential for enhancing SY, OY, and quality traits. The superior performance of this group in these key areas makes them valuable candidates for future breeding programs aimed at increasing overall productivity and improving oil quality.

- •

Group 2 (acc-192, acc-124, acc-377, acc-112, acc-1, acc-386, acc-55, acc-331, acc-235, acc-302, acc-375, acc-72, acc-171, acc-98, and acc-20) exhibited a distinct profile, demonstrating particular suitability for water management strategies. Their early flowering patterns, combined with high stomatal density and conductance traits, suggest that these accessions possess inherent drought-tolerance mechanisms. These findings are significant for developing cultivars that can thrive in water-limited environments, which are becoming increasingly prevalent owing to climate change.

In conclusion, the identification of these two distinct groups highlights the rich genetic diversity within B. carinata and underscores the potential for targeted breeding efforts to enhance its agronomic performance. Further evaluation across multiple locations is recommended to assess commercial suitability. Future research on the molecular mechanisms underpinning these traits will be crucial for optimizing breeding strategies and realizing the full potential of these promising accessions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Y.D.A. conceived and conducted the experiments, collected and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. A.G.A. managed the project, whereas T.M.O. assisted with the data analysis. B.M.A. oversaw the field trial and data collection. All the authors contributed to the design of the study and also reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by an institutional collaboration between the Norwegian University of Life Sciences and Hawassa University, Phase-IV Project (NMBU-HU-ICP-IV and ETH-13/0027).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Norwegian University of Life Sciences and Hawassa University institutional collaboration project for funding, the Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute for supplying plant materials, and the Holeta Agricultural Research Center for their assistance with additional plant materials, research field management, and data collection.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The study data are provided within the supporting information files, and if additional data are needed, it will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.