Adherence to the EAT-Lancet Diet is Not Associated With Weight Status in a Latin American Urban Multicentric Study

Abstract

The overweight/obesity high prevalence and the effects of climate change in Latin America underscores the possible positive outcomes of adopting a healthy and sustainable diet to respond to the region’s burden of nutrition-related noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). However, research on adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet in Latin America and its association with overweight/obesity is limited. This study explores the relationship between the EAT-Lancet diet adherence and overweight/obesity in a cross-sectional and urban multicentric study involving 6683 participants aged 15–65. Adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet was evaluated using the Planetary Health Diet Index (PHDI). The findings indicate that high adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet (fifth quintile) was not significantly associated with overweight/obesity (reference: first PHDI quintile, PR: 1.057, CI: 0.993–1.125, p-trend = 0.140) after adjusting for key covariates. Equivalent outcomes were found when assessing adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet using the EAT-Lancet Index, the World Index for Sustainability and Health (WISH), and the Healthy and Sustainable Diet Index (HSDI), after adjusting for the same variables. The persistently high prevalence of overweight/obesity among different adherence levels to the dietary pattern and the study’s design, do not appear to be the key factors contributing to the lack of association between these variables. Instead, the considerably low adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet in the sample as well as the low variability in adherence across participants with and without excess weight might help explain the lack of observed association. However, further research is needed to verify this conclusion.

1. Introduction

The main cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide is noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), with overweight/obesity (excess weight) as significant risk factors [1–3]. Currently, the mean consumption of healthy foods is substantially below ideal levels, while the intake of unhealthy foods continues to rise, contributing to the growing prevalence of excess weight. This trend not only increases the burden of nutrition-related NCDs and excess weight but also leads to environmental degradation [4].

In response, a healthy and sustainable reference diet was proposed by the EAT-Lancet Commission to reform global food systems, improving human health while decreasing environmental impact. The EAT-Lancet diet is a predominantly plant-based pattern, and such diets, when compared to nonvegetarian diets, have been linked to a lower risk of obesity and nutrition-related diseases, as well as benefits for metabolic, cardiovascular, and cognitive health [5–7]. While the EAT-Lancet diet and other plant-based diets share similarities in promoting plant-derived foods, it stands out by incorporating both health and environmental sustainability into a framework that could be adapted to diverse global contexts [4].

According to the EAT-Lancet Commission report, the proposed diet emphasizes, based on nutritional epidemiology, the predominant consumption of nuts and seeds, vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, and unsaturated oils. It also recommends low to moderate consumption of fish, seafood, poultry, and dairy, and minimum consumption of red and processed meat, animal fats, and added sugars [4, 8, 9].

The EAT-Lancet Commission estimates that adopting this reference diet could potentially prevent up to 23.6% (11.6 million) deaths per year worldwide by lowering the incidence of nutrition-related NCDs, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and stroke, while reducing environmental impacts as well [4]. This raises the question of whether the body mass index (BMI) differs between individuals who closely follow the EAT-Lancet diet and those who do not. This is particularly pertinent as various studies suggest that the positive impacts of the EAT-Lancet diet on the risk of certain NCDs and mortality are largely mediated by the BMI [10–12]. Even though overweight/obesity are considered significant risk factors for diet-related NCDs [2], research on the relationship between adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet and overweight/obesity is limited and presents mixed results.

Findings from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil)2010 [9], the Danish Diet, Cancer and Health Cohort study [13], the National Health and Nutrition Survey of Mexico (ENSANUT 2018–2019) [14], and the Multiethnic Cohort Study in Hawaii and Los Angeles, USA [15] have indicated that a more similar diet to the EAT-Lancet diet is linked to a lower prevalence or risk of overweight/obesity, elevated BMI, and waist circumference. In contrast, studies from the Finnish Institute of Health and Welfare [16], the Brazilian National Dietary Survey 2017–2018 [17], and the Canadian Community Health Survey-Nutrition (cycles 2004 and 2015) [18] did not find a significant connection between the reference diet adherence and excess weight. Furthermore, even with a lower total energy intake (TEI) than that of the EAT-Lancet diet, obesity rates in India continue to rise [19]. Additionally, a Swedish study even reported a slight increase in BMI among men who followed the EAT-Lancet diet more closely [11].

Given the high prevalence of diet-related NCDs in Latina America [20], adopting a healthy and sustainable dietary pattern could substantially reduce the region’s burden of these diseases and climate change effects [21]. A previous study using data from the Latin American Study of Nutrition and Health (ELANS), a multicenter study conducted in urban areas across eight Latin American countries, found a low adherence rate (29.7%) to the EAT-Lancet diet across all countries [22]. The study showed that greater adherence was linked to a higher risk of inadequate intake of cobalamin, vitamin D, and calcium, while reducing the risk of inadequate intake of pyridoxine, folate, vitamin C, magnesium, and zinc [22]. Despite this evidence, a deeper understanding of the adherence to a sustainable diet and the prevalence of other health outcomes, such as overweight and obesity, is essential for public health stakeholders to make informed decisions and promote dietary patterns aligned with sustainable food systems.

Currently, research on the EAT-Lancet diet adherence in Latin America and its relationship with overweight and obesity remains limited, as most studies on this topic have been conducted in the Global North, including Canada [18], the United States of America [15], and Europe [13, 16]. This study, using data from the ELANS sample, aimed to evaluate the association between the EAT-Lancet diet adherence and the prevalence of excess weight among the urban population in the region.

2. Materials and Methods

This study shares several methodological aspects with the previous study published by Vargas-Quesada et al. [22], which are briefly described below.

2.1. Design, Setting, and Participants

This study analyzed baseline data from the ELANS, a regional survey with cross-sectional design performed between 2014 and 2015 in eight countries of Latin America [23–25]. The ELANS employed a multistage probability sampling strategy to assess anthropometric characteristics, dietary patterns, and physical activity levels (PALs) in urban populations, representing over 80% of the region’s inhabitants [23]. The initial sample included 9218 participants, but individuals with unreported PALs were excluded based on standardized protocols [26, 27 ], which resulted to a final analytical sample of 6683 adolescents (15–18 years) and adults (19–65 years).

2.2. Ethical Considerations

The ELANS protocol received ethical approval from several institutions, including the Western Institutional Review Board (Approval No. 20140605) and each country corresponding IRB. Additionally, it was listed on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02226627). Furthermore, on June 21, 2023, the Scientific and Ethics Committee of the Costa Rican Institute for Research and Education in Nutrition and Health (INCIENSA) granted approval for this study (Approval No. IC-2023-02). The study adhered to ethical guidelines, securing informed consent from adults and assent with guardian consent for minors.

2.3. Data Collection: Sociodemographic, Anthropometric, and Dietary Intake

Sociodemographic data, including sex, age, and socioeconomic status (SES), were collected using structured questionnaires [28]. SES classification followed national standards, categorizing participants as low, middle, or high [23, 28].

Anthropometric data were gathered by trained nutritionists using standardized protocols [29]. Weight status was determined using categorized BMI based on the age-specific WHO recommendations [30, 31]. Participants with underweight or normal weight were grouped as non-overweight/obesity, while those with overweight or obesity were classified as a single category.

PALs were determined using the validated Spanish translation of the long-form International Physical Activity Questionnaire [23]. Overall PALs and the classification of participants according their PALs (low, moderate, or high) were performed following the recommended methodology [25, 32, 33].

Food consumption was determined using two nonconsecutive 24-h dietary recalls (24-h), ensuring representation of both weekdays and weekends [25]. Data were collected by trained interviewers under nutritionist supervision. Nutrient intakes were analyzed using the NDS-R software [34], accounting for national food fortification policies [25, 28]. The estimation of usual dietary intake of total energy and the 16 components of the Planetary Health Diet Index (PHDI) was conducted using the Multiple Source Method [35, 36].

2.4. PHDI

The PHDI quantifies the EAT-Lancet diet adherence by assessing dietary patterns based on energy intake distribution [8, 37]. It includes 16 components grouped into four categories: adequacy (nutrient-rich foods), optimum (balanced health-effect foods), ratio (proportional intake measures), and moderation (foods to be limited) [4, 8].

For analytical consistency, all reported foods were disaggregated into individual ingredients and assigned to PHDI components, as recommended by Cacau et al. [8]. Ultra-processed food items underwent further decomposition to quantify the content of vegetable oil, saturated fat, and added sugars. This classification process was independently reviewed by trained nutritionists to ensure accuracy and reduce potential bias.

According to Cacau et al. [8], the PHDI score ranges from 0 to 150, with higher values reflecting greater conformity to the EAT-Lancet diet. To standardize comparisons, dietary adherence can also be expressed as a proportion of the maximum PHDI score [17]. Additional methodological details on PHDI development, scoring criteria, cutoff thresholds, and validation procedures can be found in prior studies [8].

2.4.1. Alternative EAT-Lancet Diet Indices

To validate the results, analyses were also conducted using other indices designed to assess the EAT-Lancet diet adherence: the EAT-Lancet Diet Index (ELDI) [11], the World Index for Sustainability and Health (WISH) [38], and the Healthy and Sustainable Diet Index (HSDI) [14]. The methodologies for calculating each index differ slightly from that of the PHDI [8]; however, their main objective is to evaluate from different approaches how well diets adhere to the EAT-Lancet diet.

2.4.1.1. ELDI

The ELDI created by Stubbendorff et al. [11], consists of 14 components grouped into two categories; those that should be prioritized and those that should be restricted. The scoring of each component ranges from 0 to 3 points, depending on how well one follows the daily intake recommendations for each food group. For the prioritized components, the lowest adherences is represented with a score of 0, while the greatest adherence with a score of 3. In contrast, the rating for the limited components is reversed. As a result, the score can fall between 0 and 42 points. The ELDI was originally developed to validate the relationship between the EAT-Lancet diet and mortality in the Malmö Diet and Cancer cohort (n = 22,241) with a mean relative adherence of 42.6% (17.9 points out of 42). All-cause, cancer and cardiovascular mortality were lower in the highest adherence (≥23 points) group compared to the lowest adherence (≤13 points) group [11].

2.4.1.2. WISH

Developed by Trijsburg et al. [38], the WISH includes 13 components. Each component is assigned a score on a scale of 0–10 points, where 0 signifies no adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet while 10 indicates full adherence. The overall WISH index score can fall between 0 and 130 points. The WISH was validated using duplicate 24-h from 396 urban Vietnamese male and female participants with a mean adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet of 35.4% (46 points out of 130). Initial findings indicated that the WISH was effective in distinguishing healthy and sustainable diets [38].

2.4.1.3. HSDI

The HSDI developed by Shamah–Levy et al. [14], comprises 13 food groups. The proportional energy contribution from each food group is evaluated against its recommended intake. A binary system is then used to assign 1 point to a food group if the energy contribution recommendation is met, and 0 points if it is not. The HSDI score can fall between 0 and 13 points. Using from the Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey (2018–2019), a large sample of adults (n = 11,506) was used to validate the HSDI. The mean relative EAT-Lancet diet adherence in this sample was 51.5% (6.7 points out of 13). Notably, males with elevated HSDI scores had a reduced prevalence of obesity; however, no significant association was observed among female participants [14].

2.5. Data Analyses

The Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to assess the normality assumption for continuous variables. Medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) were used to report continuous variables, while frequencies (%) were used for categorical variables. Differences in TEI and PHDI scores among categories of sex, age group, country, SES, PALs, and weight status were assessed using the Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests, with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. Participant frequency distributions across PHDI quintiles were analyzed using Chi-square tests.

Poisson regression models with robust variance controlled for key covariates (including sex, age, TEI, SES, PALs, and country) were used to assess the association between the EAT-Lancet diet adherence (PHDI) and the prevalence of weight excess. This modeling approach was chosen over logistic regression due to its ability to produce risk estimates with narrower confidence intervals and prevent the overestimation of risk, which can occur in cross-sectional studies with highly prevalent outcomes (≥10%) [39–43]. Additional Poisson regression models examined associations between overweight/obesity and alternative dietary indices derived from the EAT-Lancet framework (PHDI, ELDI, WISH, and HDSI). In these models, each index was treated as a continuous variable to explore individual associations with the outcome of interest.

Trend analyses were performed using orthogonal polynomial contrasts, incorporating linear, quadratic, cubic, quartic, and joint trend assessments within PHDI quintiles. Multicollinearity was detected using the variance inflation factor, while over-dispersion was assessed using negative binomial models. Age group and sex categories were used to conduct stratified analyses in order to explore potential confounding effects in multiadjusted models. Separate Poisson models treated PHDI as an ordinal variable (quintiles) and alternative EAT-Lancet indices as continuous predictors, with results presented in the Supporting Information Tables S1–S4.

Statistical tests were performed two-tailed, with significance set at p < 0.05. Data processing and analysis were conducted in Stata (version 14.1, College Station, TX, USA) [44], IBM SPSS (version 27, IBM Corp.) [45], and jamovi (version 2.3.28) [46].

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics, Energy Intake, and PHDI

A total of 6683 participants with a mean age of 36.0 ± 14.1 years (data not shown) were included in the study sample. Most of the participants were female (51.8%), within the age range of 19–59 years (83.0%), of low SES (52.0%), with low PALs (58.9%), and participants with overweight/obesity (60.0%) (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Total | TEI (kcal) | p-Value2 | PHDI score (points) | p-Value2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%)1 | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | |||

| Overall | 6683 (100) | 1882 | 584 | — | 44.3 | 12.5 | — |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 3223 (48.2) | 2087 | 569 | <0.001 | 44.5 | 13.0 | 0.472 |

| Female | 3460 (51.8) | 1699 | 478 | — | 44.3 | 12.1 | — |

| Age group | |||||||

| 15–18 years | 683 (10.2) | 2028a | 590 | <0.001 | 43.2a | 13.0 | 0.008 |

| 19–59 years | 5544 (83.0) | 1880b | 582 | — | 44.4b | 12.5 | — |

| 60–65 years | 456 (6.8) | 1688c | 513 | — | 45.1b | 12.2 | — |

| Country | |||||||

| Argentina | 885 (13.2) | 1961a | 690 | <0.001 | 38.2a | 11.7 | <0.001 |

| Brazil | 1444 (21.6) | 1800b | 585 | — | 47.3b | 12.2 | — |

| Chile | 611 (9.1) | 1748b | 494 | — | 44.2c | 11.4 | — |

| Colombia | 879 (13.2) | 1927a | 564 | — | 41.8d | 11.3 | — |

| Costa Rica | 564 (8.4) | 1815b | 577 | — | 49.2e | 12.9 | — |

| Ecuador | 557 (8.3) | 2027c | 559 | — | 46.5b | 10.7 | — |

| Peru | 877 (13.1) | 1959a | 538 | — | 44.0c | 11.6 | — |

| Venezuela | 866 (13.0) | 1826b | 519 | — | 44.9c | 12.3 | — |

| Socioeconomic status | |||||||

| Low | 3479 (52.0) | 1886a | 607 | 0.022 | 44.0a | 12.3 | <0.001 |

| Middle | 2546 (38.1) | 1897b | 559 | — | 44.7b | 13.1 | — |

| High | 658 (9.9) | 1908b | 560 | — | 45.4c | 11.7 | — |

| Physical activity level | |||||||

| Low | 4,024 (60.2) | 1820a | 545 | <0.001 | 44.4a | 12.5 | 0.037 |

| Moderate | 1832 (27.4) | 1911b | 580 | — | 44.1a | 12.3 | — |

| High | 827 (12.4) | 2107c | 635 | — | 45.1b | 12.9 | — |

| Weight status3 | |||||||

| Non-overweight/obesity | 2664 (39.9) | 1910 | 578 | <0.001 | 44.0 | 12.9 | 0.009 |

| Overweight/obesity | 4019 (60.1) | 1863 | 579 | — | 44.6 | 12.3 | — |

- Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; PHDI, Planetary Health Diet Index; TEI, total energy intake.

- a,b,c,d,eMedian values within the same variable that do not share a common letter are significantly different (p < 0.05).

- 1Values are presented as frequencies (%) or medians (IQR), unless otherwise specified.

- 2p-value is derived from the Mann–Whitney or Kruskal–Wallis tests used for group comparisons.

- 3Weight status based on BMI categories.

The median TEI and PHDI score of the sample were 1882 kcal/day (IQR: 584) and 44.3 points (IQR: 12.5) out of 150, respectively (Table 1). The TEI was significantly higher in male participants, the adolescents group, participants with middle–high SES and high PALs; and slightly higher in those with overweight/obesity. In contrast, TEI was lower in female participants, those aged 60–65, individuals with low SES and PALs, and those with overweight/obesity (p < 0.001). Regarding country, median TEI ranged from 1748 kcal/day (IQR: 494) in Chile to 2027 kcal/day (IQR: 559) in Ecuador, with significant differences among countries (p < 0.001) (Table 1).

A slightly higher median PHDI score was observed in the 19–59 years and 60–65 years age groups, participants with high SES and PALs, and those with overweight/obesity. In contrast, the PHDI score was lower in adolescents, individuals with low SES and low–moderate PALs, and those with overweight/obesity (p < 0.001). Significant differences in PHDI scores were observed across countries (p < 0.001) and ranged from 38.2 points (IQR: 11.7) in Argentina to 49.8 points (IQR: 12.9) in Costa Rica (p < 0.001) (Table 1). No significant differences in PHDI scores were observed between male and female participants (p = 0.472) (Table 1).

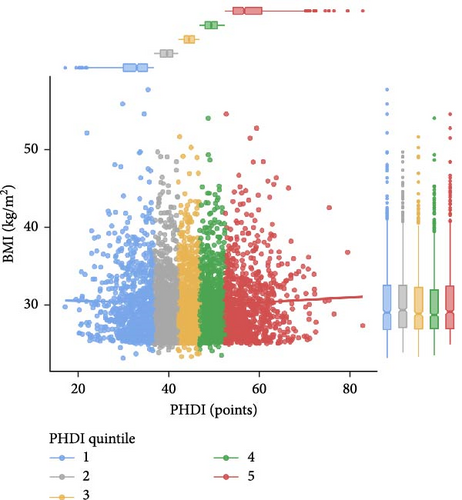

3.2. BMI and PHDI Distribution

Mean BMI values did not significantly differ among PHDI quintiles (p = 0.141) (Table 2). However, the frequency of participants with overweight/obesity according to the PHDI quintile showed a trend of higher accumulation in the second to fifth PHDI quintiles (60.8%–61.5%), compared to the first quintile (56.3%) (p = 0.035). The opposite was true for the participants without overweight/obesity.

| Characteristics1 | Total | PHDI quintile2 | p-Value3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | Third | Fourth | Fifth | |||

| Overall, n (%) | 6683 (100.0) | 1337 (20.0) | 1336 (20.0) | 1337 (20.0) | 1337 (20.0) | 1336 (20.0) | — |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.9 ± 5.5 | 26.7 ± 5.7 | 27.1 ± 5.5 | 26.9 ± 5.5 | 26.9 ± 5.3 | 27.0 ± 5.6 | 0.141 |

| Weight status4, n (%) | |||||||

| Non-overweight/obese | 2664 (39.9) | 584 (43.7)a | 526 (39.2)b | 517 (38.8)b | 523 (39.1)b | 514 (38.5)b | 0.035 |

| Overweight/obese | 4019 (60.1) | 753 (56.3)a | 814 (60.8)b | 817 (61.2)b | 813 (60.9)b | 822 (61.5)b | — |

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; PHDI, Planetary Health Diet Index.

- a,bValues within the same row that do not share a common letter are significantly different (p < 0.05).

- 1Values are presented as frequencies (%) or means ± SD, unless otherwise specified.

- 2PHDI quintiles (min–max score): first: 13.4–36.7; second: 36.8–42.0; third: 42.1–46.8; fourth: 46.9–52.2; fifth: 52.3–82.8.

- 3p-value is derived from the Chi-square test used to compare frequencies across PHDI quintiles.

- 4Weight status based on BMI categories.

The distribution of the BMI among participants with overweight/obesity showed that the BMI values are widely distributed across all PHDI quintiles (Figure 1). This widespread distribution of BMI values limits the ability to establish a clear trend in the relationship between the EAT-Lancet diet adherence (PHDI) and excess weight, evidenced in similar values for BMI medians among PHDI quintiles (right-side box plot, Figure 1).

3.3. Association Between the EAT-Lancet Diet Adherence and Overweight/Obesity Prevalence

Regarding overweight/obesity prevalence, the unadjusted model indicated a 9.2% significantly higher prevalence of excess weight observed among participants with high adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet (fifth PHDI quintile) compared to those with low adherence (first PHDI quintile) (p-trend = 0.013). However, after controlling for sex and age (Model A1), no significant difference in the prevalence of overweight/obesity was found between participants with high adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet and those with low adherence (p-trend = 0.112). Similarly, after full adjustment in the model (Model B1: adjusted for sex, age, TEI, country, SES, and PALs); participants with high EAT-Lancet diet adherence did not have significantly higher prevalence of excess weight compared to those with low adherence (p-trend = 0.140) (Table 3). In addition, no significant associations were found for quadratic, cubic, quartic, or joint trends (p-trend > 0.05, data not shown).

| Models | PHDI quintile | Overweight/obesity | p-Valueb | p-trendc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRa | 95% CI | ||||

| Unadjusted | — | — | — | 0.047 | 0.013 |

| First | ref | ref | — | — | |

| Second | 1.079 | 1.012–1.150 | 0.019 | — | |

| Third | 1.086 | 1.019–1.158 | 0.011 | — | |

| Fourth | 1.081 | 1.014–1.152 | 0.017 | — | |

| Fifth | 1.092 | 1.025–1.164 | 0.006 | — | |

| Model A1d | — | — | — | <0.001 | 0.112 |

| First | ref | ref | — | — | |

| Second | 1.051 | 0.990–1.117 | 0.103 | — | |

| Third | 1.048 | 0.987–1.113 | 0.128 | — | |

| Fourth | 1.051 | 0.989–1.117 | 0.106 | — | |

| Fifth | 1.056 | 0.994–1.121 | 0.075 | — | |

| Model B1e | — | — | — | <0.001 | 0.140 |

| First | ref | ref | — | — | |

| Second | 1.052 | 0.990–1.117 | 0.103 | — | |

| Third | 1.045 | 0.984–1.110 | 0.155 | — | |

| Fourth | 1.046 | 0.983–1.112 | 0.152 | — | |

| Fifth | 1.057 | 0.993–1.125 | 0.083 | — | |

- Note: Poisson regression analysis with robust variance estimation: aPrevalence ratio of overweight/obesity comparing the fifth PHDI quintile to the first quintile (reference group). bp-value is derived either from the overall test of the model or the Wald test applied to each PHDI quintile as a categorical variable within the model. cp-value for trend is derived from the linear trend across PHDI quintiles within each model. PHDI quintiles (min–max score): first: 13.4–36.7; second: 36.8–42.0; third: 42.1–46.8; fourth: 46.9–52.2; fifth: 52.3–82.8. dModel A1: Adjusted for sex and age. eModel B1: Adjusted for sex, age, total energy intake, country, socioeconomic status, and physical activity level.

- Abbreviation: PHDI, Planetary Health Diet Index.

As a validation of the previously established absence of relationship between the EAT-Lancet diet adherence and excess weight status, the other three indices (ELDI, WISH, and HSDI) used to evaluate the EAT-Lancet diet adherence also showed no association with excess weight after controlling for sex and age (Model A2), and for sex, age, TEI, country, SES, and PALs (Model B2) (Table 4).

| Model | Index | Overweight/obesity | p-Valueb | Global test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRa | 95% CI | p-Valuec | |||

| Unadjusted | PHDI | 1.003 | 1.001–1.005 | 0.008 | 0.008 |

| ELDI | 1.005 | 0.999–1.011 | 0.115 | 0.115 | |

| WISH | 1.000 | 0.999–1.002 | 0.731 | 0.731 | |

| HSDI | 1.009 | 0.994–1.025 | 0.246 | 0.246 | |

| Model A2d | PHDI | 1.001 | 0.999–1.003 | 0.181 | <0.001 |

| ELDI | 0.999 | 0.993–1.005 | 0.741 | <0.001 | |

| WISH | 0.999 | 0.998–1.007 | 0.283 | <0.001 | |

| HSDI | 0.989 | 0.974–1.004 | 0.136 | <0.001 | |

| Model B2e | PHDI | 1.001 | 0.999–1.004 | 0.210 | <0.001 |

| ELDI | 1.000 | 0.994–1.006 | 0.909 | <0.001 | |

| WISH | 1.000 | 0.998–1.001 | 0.808 | <0.001 | |

| HSDI | 1.002 | 0.986–1.017 | 0.846 | <0.001 | |

- Note: Poisson regression analysis with robust variance estimation: aPrevalence ratio of overweight/obesity for each EAT-Lancet index. bp-value is derived from the Wald test for each index as a continuous variable with each model. cp-value is derived from the overall test of the model. dModel A2: adjusted for sex and age. eModel B2: adjusted for sex, age, total energy intake, country, socioeconomic status, and physical activity level.

- Abbreviations: ELDI, EAT-Lancet Diet Index; HSDI, Healthy and Sustainable Diet Index; PHDI, Planetary Health Diet Index; WISH, World Index for Sustainability and Health.

Additional stratified modeling analyses by sex (male and female) and age group (adolescents and adults) also revealed no significant associations, whether using PHDI in quintiles as an ordinal variable or using a different EAT-Lancet index as a continuous variable in each model (Supporting Information Tables S1–S4).

Correlation analyses among indices used to assess the EAT-Lancet diet adherence showed significantly positive correlations between the PHDI and each additional index (ELDI: rs = 0.62; WISH: rs = 0.55; HSDI: rs = 0.50; p < 0.001) (data not shown).

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess the relationship between the EAT-Lancet diet adherence and the prevalence of overweight/obesity (excess weight) among the urban population in the region. It presents some methodological similarities to an earlier study published by Vargas-Quesada et al. [22], as both studies use the ELANS dataset and the PHDI score as a numerical indicator of adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet. However, this is the first research to explore the association between adherence to the reference diet and the excess weight prevalence among urban populations in eight countries of Latin America.

We observed that high adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet did not show a significant association with a lower prevalence of overweight/obesity. This finding contrasts with those observed in the ELSA-Brasil (2008–2010) [9] and the Multiethnic Cohort Study in Hawaii and Los Angeles, USA [15], which reported positive associations between adherence to the reference diet and a lower excess weight prevalence. However, results from the Finnish Institute of Health and Welfare [16] and the Brazilian National Dietary Survey 2017–2018 [17] align with our findings. The lack of association was confirmed in this study by applying other indices (ELDI, WISH, and HSDI) designed to assess adherence to the reference diet, to the same sample, confirming that the results were consistent regardless of the index used.

Another factor that could explain why high adherence to the reference diet did not correlate with excess weight in our study is the high prevalence of this outcome within the ELANS participants, which is uniformly distributed across all PHDI quintiles (Table 1 and Figure 1). This uniformity makes it challenging to associate a higher prevalence of overweight/obesity with participants’ adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet. However, the Multiethnic Cohort Study in Hawaii and Los Angeles found association between adherence to the reference diet and overweight/obesity, despite a similar prevalence of overweight/obesity (58.7%) compared to our study (60.1%) [15]. This suggests that obesity prevalence may not be a significant factor influencing the relationship between adherence and the prevalence or risk of overweight/obesity. Although the ELANS data were collected in 2014–2015, the study’s results would likely be consistent even if conducted more recently, as the prevalence of excess weight in both male and female participants has steadily increased across all Latin American countries since 1975 [47, 48].

The adherence level to the EAT-Lancet diet could be a critical factor in its association with overweight/obesity. Considering the study design (cross-sectional), it is possible that individuals with overweight/obesity may have adopted plant-based dietary habits, such as the EAT-Lancet diet, for weight management and the prevention of related comorbidities. This complicates the understanding of why adherence to the reference diet did not correlate with excess weight. Nevertheless, studies with different designs (cross-sectional or longitudinal), such as those conducted by Cacau et al. [8, 9] and Klapp et al. [15], which found greater adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet (40.2% and 52.1%, respectively), observed a significant negative correlation between adherence and excess weight. Additionally, in the Klapp et al. research [15], the highest percentage of participants with excess weight was concentrated in the lower adherence groups to the reference diet, rather than being evenly distributed across all adherence levels as observed in our study.

In this study, the median adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet was relatively low, at 29.5%, ranging from 25.5% in Argentina to 32.8% in Costa Rica. Similarly, other studies with different designs, such as those conducted by Marchioni et al. [17] and Suikki et al. [16], which reported lower relative adherence (30.6% and 27.7%, respectively), also failed to demonstrate a relationship between adherence to the reference diet and excess weight. This suggests that, more important than the study design, the lower adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet, combined with the narrow range of variation in PHDI score values observed across the study sample, could explain the difficulty in distinguishing the higher prevalence of overweight/obesity among participants according to their degree of adherence to the dietary pattern, as previously suggested by Suikki et al. [16]. This evidence is supported by two cross-sectional studies conducted in Brazil [9, 17], both of which reported similar prevalence of overweight/obesity: 58.4% for ELSA-Brasil 2008–2010 [49] and 52.9% for the Brazilian National Dietary Survey 2017–2018 [17]. An association between excess weight and adherence to the reference diet was identified only in the study with relatively high adherence (≥40%) [9]. In contrast, no association was found in the other study, where adherence was lower (30.6%) [17]. Despite this evidence, further studies are required to validate our explanation for the results of this study.

However, the observed low adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet in this study may be due to factors not explored here. The literature suggests that economic challenges and systemic barriers are major factors influencing adherence to the reference diet. Implementing this dietary pattern requires substantial investments in transforming food systems, including changes in land use, production methods, storage, distribution, and waste management [50, 51]. Additionally, like other healthy diets, its economic viability remains uncertain [51]. Socioeconomic disparities, especially in Latin American region [52], worsen affordability issues, making it harder to adopt. These inequities in accessing affordable, nutritious foods could significantly hinder the implementation of the EAT-Lancet diet in the Latin American region. This is especially important because food systems, regardless of their typology, are failing to provide adequate nutrition, environmental sustainability, health results, and equity and inclusion for everyone [53].

Cultural dietary preferences also play a crucial role, as the EAT-Lancet diet may not sufficiently account for diverse food traditions and practices [50, 51]. It is essential to respect cultural diversity in food systems and promote dietary recommendations that align with local culinary values. If the diet is perceived as incompatible with cultural norms, its adoption will likely remain limited [54].

Additionally, a lack of knowledge or understanding of the EAT-Lancet diet is another critical factor. It is necessary to ensure the equitable distribution of information and education on sustainable diets. Even with accurate information, adherence depends on individuals’ ability to afford and access the resources needed for dietary changes, assuming they are open to adjusting their food culture [50, 51].

This study has notable strengths that enhance the reliability of its findings: First, dietary data were collected using the 24-h dietary recall (24-h) method, which provides high accuracy. This is particularly important given that two 24-h were conducted for the entire sample. Second, the PHDI scoring system allows for precise quantification of intermediate dietary intakes, improving adherence assessment compared to indices that rely on binary food categorizations [37]. Third, the large analytical sample, restricted to plausible energy reporters, contributed to greater statistical precision, reduced outlier effects, and minimized estimation errors. Fourth, the analyses with Poisson regression models with robust variance ensured a methodologically sound approach for assessing the association between dietary adherence and excess weight prevalence, avoiding the risk overestimation inherent in logistic regression.

Also, several limitations in this research should be considered: First, the sample was limited to urban settings, meaning the findings cannot be generalized to rural areas. Second, cross-sectional study design only allows for associative conclusions, precluding any inference of causality. Additionally, individuals with overweight or obesity may have already altered their dietary habits (e.g., adopting a plant-based diet) as part of a weight management strategy, influencing observed associations. Third, ultra-processed foods were separated to estimate their content of critical ingredients (added sugar, vegetable oils, and animal fats), which a method susceptible to bias. To mitigate potential errors, this classification underwent independent review by four trained nutritionists. Fourth, while statistical models adjusted for key confounders (sex, age, TEI, country, SES, and PALs), additional factors—such as stress, sleep patterns, and food security—were not accounted for, potentially influencing the prevalence of overweight/obesity in the study sample. Fifth, the 24-h method, although a frequently employed used dietary assessment tool, is susceptible to recall bias, misreporting, and interviewer influence. To enhance data accuracy, all dietary recalls were supervised by trained nutritionists, and portion sizes were standardized in grams and milliliters.

5. Conclusion

Our study did not identify a significant relationship between excess weight prevalence and the adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet in a Latin American multicentric study. The consistently high prevalence of overweight/obesity across all levels of adherence to the reference diet and the study’s design do not appear to be key factors in explaining this lack of association. Instead, the relatively low adherence to the reference pattern within the study sample and the low variability in adherence across participants with and without excess weight could help explain the lack of a significant association. However, future studies are needed to confirm this conclusion. Further studies with longitudinal designs that consider structural barriers to adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet, such as food accessibility and affordability, as well as other factors (beyond dietary patterns, physical activity, and sociodemographics) that influence excess weight, might provide more comprehensive insights to confirm the absence of association between adherence to the reference diet and the prevalence of overweight/obesity.

Ethics Statement

The Western Institutional Review Board approved the ELANS protocol (Approval No. 20140605), and it was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (Registration No. NCT02226627). It also received approval from the local IRBs in each participating country. Written informed consent was provided by all adult individuals before participating in the survey, while minor participants (aged 15–18 years) provided written informed assent and obtained guardian consent through signed forms. To ensure voluntary participation, an independent witness unaffiliated with the research team cosigned the assent forms for minors. Additionally, on June 21, 2023, the Scientific and Ethics Committee of INCIENSA approved this study protocol (Approval No. IC-2023-02).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Rulamán Vargas-Quesada was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, data curation, software, formal analysis, project administration, and supervision, and also wrote the original draft. Rafael Monge-Rojas, Georgina Gómez, and Juan José Romero-Zúñiga contributed to methodology and supervision. All authors participated in the investigation and in reviewing and editing the original draft.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no acknowledgments to declare. No artificial intelligence software has been used to prepare this manuscript.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.