How Digital Self-Efficacy Boosts Employment Hope: A Multigroup Analysis Across Organizational Levels

Abstract

The digital transformation of the workplace reshapes career development, making digital confidence a critical factor in employability. Beyond technical skills, individuals must also believe in their ability to navigate digital environments and adapt to evolving job demands. Digital self-efficacy (DSE) represents this belief, influencing how individuals perceive their career prospects and ability to succeed in technology-driven workplaces. While self-efficacy has been widely studied in career research, less attention has been paid to DSE, and even less is known about how its impact on employability perceptions varies across organizational hierarchies. This study examined the extent to which DSE predicts employment hope (EH), a psychological construct that captures employability perceptions through psychological empowerment (PE) and goal-oriented pathways (GOPs), and whether this relationship differs among senior executives, middle managers, and operational-level staff. Using survey data from 471 workers in Ecuador, we applied partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLSs-SEM) to test the DSE and EH dimensions, and multi-group analysis (MGA) to assess group differences. The results indicate that DSE positively influences both PE and GOP, reinforcing its role as a key psychological resource for employability. However, the effect of DSE on GOP is significantly stronger among senior executives than among the other groups, suggesting that individuals in higher positions can more effectively channel their digital confidence in career planning and strategic decision-making. In contrast, the relationship between DSE and PE remains consistent across all job levels, indicating that DSE fosters career confidence, regardless of organizational rank.

1. Introduction

The modern job market is evolving owing to rapid technological advancements, automation, and changing employment landscapes [1]. Digital transformation is no longer limited to the technological sector. This reshapes career trajectories across industries [2]. Employers now seek professionals who can navigate digital environments, analyze data, and leverage technology to improve their performance [3, 4]. Technical expertise alone is insufficient [5, 6]. Success depends not only on having digital skills but also on the confidence to apply them effectively in complex and evolving environments [7].

Digital self-efficacy (DSE) refers to an individual’s confidence in their ability to use digital tools, learn new technologies, and solve digital challenges [8]. Studies suggest that individuals with higher DSE exhibit greater career adaptability, workplace resilience, and learning agility [9–11]. Despite the growing relevance of this construct, limited research has examined whether its influence on employability perceptions differs according to organizational role. Individuals occupying different levels of responsibility within organizations, such as senior executives, middle managers, and operational-level staff, may translate digital confidence into career opportunities in diverse ways [12, 13].

Employment hope (EH) is a psychological construct that reflects an individual’s motivation, perceived control, and goal-setting capacity in career development [14–16]. It consists of two dimensions: psychological empowerment (PE), which represents individuals’ perceived control over their career outcomes, and goal-oriented pathways (GOPs), which reflect the ability to plan and pursue career strategies. Unlike traditional measures of employability that emphasize external labor conditions, EH focuses on internal psychological readiness.

Grounded in social cognitive theory (SCT) [17], self-efficacy influences how people set goals and engage in career behaviors. This perspective is complemented by the conservation of resources (CORs) theory [18], which suggests that individuals strive to build and preserve personal resources to manage uncertainty. From this dual-theoretical perspective, DSE can be viewed as a psychological resource that enhances EH. Whether this dynamic varies across hierarchical levels remains unclear.

The extent to which individuals leverage DSE for empowerment and goal setting may depend on their organizational position. Senior executives often possess greater autonomy and decision-making authority, which may help them convert their digital confidence into strategic career moves. Middle managers might face structural pressures that limit this capacity, while operational-level staff often lack influence over their career progression [19, 20]. Therefore, the relationship between DSE and EH may not be consistent across organizational hierarchical levels.

This study explored how DSE fosters EH across hierarchical levels using multigroup analysis (MGA). Specifically, it examines whether DSE differentially predicts the dimensions of EH (PE and GOP) among senior executives, middle managers, and operational-level staff members.

By integrating DSE into employability research, this study contributes to understanding how psychological resources shape career perceptions in digital work environments. It also explores the extent to which organizational hierarchy moderates the effects of DSE on employability-related outcomes. This is particularly relevant in a job market characterized by continuous technological change and uncertainty.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: First, the literature on DSE, EH, and theoretical perspectives on job-related resources are reviewed. Next, the hypotheses are developed and the methodology is described. Finally, the findings are presented, implications discussed, and future research directions outlined.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. DSE in the Digital Era

The rapid pace of digital transformation has made digital proficiency crucial for career success [5, 6]. As organizations adopt new technologies, employees must adapt to emerging digital tools, platforms, and workflows [21, 22]. However, technical competence alone does not ensure success in digital environments [23, 24]. DSE, or confidence in using digital tools, now significantly affects workplace behavior and growth [25–27].

DSE is based on Bandura’s [28] idea of self-efficacy, meaning belief in one’s ability to perform tasks. In digital settings, DSE involves confidence in learning and using digital tools [8], influencing responses to challenges and digital learning.

High DSE correlates with digital engagement, adaptability, and proactive learning [29–31]. Employees with strong DSE pursue new technologies, experiment with digital solutions, and take initiative in upskilling [26, 27]. This belief affects responses to challenges, innovation adoption, and digital learning [11].

While DSE’s impact on workplace outcomes is noted, its effect on employability perceptions is unclear. Research shows digital proficiency enhances job market positioning [32, 33], but confidence in applying these skills professionally is crucial. DSE may influence how individuals perceive employability, pursue goals, and develop career optimism [34, 35].

2.2. Understanding EH and its Dimensions

In an uncertain job market, employability perceptions are shaped by external labor conditions and psychological factors affecting confidence in securing employment [36, 37]. EH reflects an individual’s belief in achieving career goals despite market uncertainties [14]. Unlike traditional employability measures focused on qualifications and labor demand, EH emphasizes motivational and cognitive processes shaping career optimism and perceived agency [38, 39].

EH has two dimensions: PE and GOPs. PE reflects an individual’s belief in controlling career outcomes [40]. This includes confidence in job transitions, responding to challenges, and maintaining professional direction [14]. Higher PE leads to greater career resilience and motivation. Individuals with lower PE often experience career uncertainty and disengagement [41, 42].

GOPs refer to creating and implementing career strategies to improve employability [14]. This includes behaviors such as setting goals, identifying needs, and seeking advancement [16]. Those with strong pathways invest in upskilling and adapt to market changes, while individuals with weaker pathways rely on passive strategies, limiting opportunities.

Previous research examined EH as a single construct and two distinct dimensions [39, 43]. Studies show PE and GOP are influenced by different psychological antecedents, leading to distinct outcomes despite global EH scores indicating employment optimism [15, 44]. This distinction enables better understanding of employability perceptions shaped by internal resources like DSE [45, 46]. This study analyzed PE and GOP dimensions to assess DSE’s effects on EH.

2.3. DSE as a Resource in Employability

Today’s labor market needs resources to help individuals navigate career challenges [47, 48]. While education remains important, psychological resources like self-efficacy are critical enablers of career adaptability [49, 50]. DSE enables individuals to use digital tools in digitally mediated work environments [10, 26].

The CORs theory [18] explains how DSE affects employability perceptions. COR theory states individuals seek resources for managing stress and goals [51]. In digital labor markets, DSE functions as a psychological resource that enables individuals to identify opportunities [52]. Those with higher DSE are more likely to pursue digital learning.

Self-determination theory (SDT) [53, 54] states motivation increases when individuals feel competent and control their growth. DSE fulfills these needs by fostering digital confidence. Job crafting theory [55, 56] suggests self-efficacious employees shape work to match their strengths. DSE enables individuals to remain competitive in the labor market.

Empirical studies show individuals with higher DSE report stronger job market confidence [57]. Research indicates psychological readiness plays a prominent role in employability outcomes [58]. Perceived digital ability predicts employability better than technical knowledge [11].

The relationship between DSE and EH remains understudied. EH combines PE and GOPs, capturing individuals’ agency in career development. DSE may influence EH by enhancing perceived control [26, 27, 59].

DSE’s impact on employability perceptions varies across organizational roles, making context understanding essential for developing workforce adaptation interventions.

2.4. The Relationship Between DSE and EH: A SCT Perspective

Individuals’ perceptions of employability are shaped by beliefs about capabilities [60, 61]. SCT [17, 62] explains how self-efficacy influences career outcomes. SCT posits that beliefs about task performance shape motivation and behavior, influencing how individuals interpret challenges during career transitions [63].

DSE may support employability by enhancing proactive behavior in handling digital demands. As a psychological resource, DSE could reinforce EH through perceived career control [52]. Research shows individuals with higher DSE adapt better to labor market shifts [35].

These effects relate to PE, a dimension of EH reflecting individuals’ beliefs in influencing employment outcomes. People with high DSE feel more capable of managing job demands [64], while those with lower DSE report higher uncertainty [65].

DSE may contribute to GOPs, the second dimension of EH, by influencing career development. According to SCT, self-efficacy shapes goal pursuit [28]. Those with high DSE engage in learning opportunities in technology-driven environments [66], aligning with GOP’s focus on career strategies.

While self-efficacy drives career motivation [67, 68], its role in EH remains understudied. Given digital capabilities’ importance, examining DSE’s effects on PE and GOP contributes to employability research.

2.5. Hierarchical Organizational Differences in the Relationship Between DSE and EH

Although DSE enhances EH, the effect may be shaped by organizational context. Employees at different levels face distinct demands, autonomy, and career resources [69, 70]. These differences may influence how DSE translates into empowerment and goal-directed behavior.

For PE, senior positions have greater control over career trajectory, involving decision authority and strategic responses [71, 72]. DSE may amplify their confidence in managing complex tasks, reinforcing empowerment. Operational staff rely more on organizational support and supervisor validation for career control [73, 74]. This suggests the DSE-PE relationship may be weaker in positions with lower autonomy.

Hierarchical differences may shape how DSE relates to GOPs. Upper-level roles engage more in structured career planning [75, 76], where DSE acts as a reinforcing mechanism. Middle managers and operational staff rely more on DSE for motivation when institutional career pathways are unclear [77, 78].

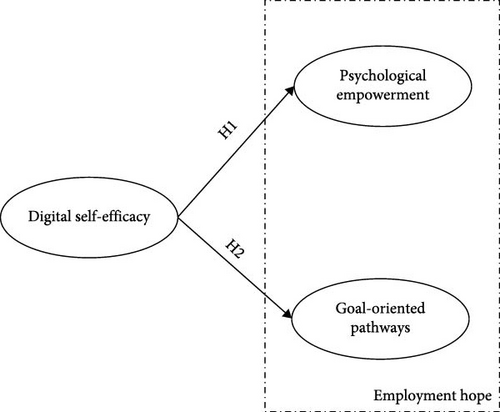

Based on these theoretical arguments, this study proposes the following hypotheses, which are visually summarized in Figure 1:

-

H1: DSE positively influences PE.

-

H2: DSE positively influences GOPs.

-

H3: The relationship between DSE and PE differs across organizational hierarchical levels (senior executives, middle managers, and operational-level staff).

-

H4: The relationship between DSE and GOPs differs across organizational hierarchical levels (senior executives, middle managers, and operational-level staff).

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection and Ethical Considerations

The data for this study were collected between June and August 2023 in the Guayaquil Metropolitan Area, Ecuador. Participants were recruited primarily through LinkedIn, a widely used platform for professional networking and labor-related interactions. In Ecuador, LinkedIn reports approximately 5.2 million users, providing access to a broad and diverse pool of working professionals across various sectors [79].

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities (FCSH) at Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral (ESPOL) under the project code FCSH-11-2022 and adhered to Ecuadorian data protection regulations. Responses were collected anonymously through Encuesta Fácil, a regional online survey platform that is commonly used in academic and institutional research. All participants were informed of the purpose of the study and provided written informed consent before starting the survey.

3.2. Participants

The study drew on a convenience sample of workers from the professional sector in Ecuador. A total of 753 individuals accessed the online survey and 517 completed it, yielding a response rate of 68.66%. To be included in the study, participants were required to be currently employed and to have held a paid occupational role for at least 12 consecutive months. After applying this criterion, 471 valid cases were retained for analysis.

The average age of the respondents was 34 years (SD = 11.30). Regarding educational attainment, 21.23% (n = 100) held a postgraduate degree, 52.44% (n = 247) held a university or technical degree, and 26.33% (n = 124) had completed a secondary or primary education. The detailed sample characteristics are presented in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 206 | 43.74 |

| Female | 261 | 55.41 |

| LGTBI+ | 4 | 0.85 |

| Age | ||

| 18–25 | 132 | 28.03 |

| 26–35 | 153 | 32.48 |

| 36–45 | 95 | 20.17 |

| 46–55 | 73 | 15.50 |

| 56–65 | 16 | 3.40 |

| +65 | 2 | 0.42 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 271 | 57.54 |

| Married | 158 | 33.55 |

| Divorced | 38 | 8.07 |

| Widowed | 4 | 0.85 |

| Education degree | ||

| Primary school | 6 | 1.27 |

| High school | 118 | 25.05 |

| Technical | 57 | 12.10 |

| University | 190 | 40.34 |

| Specialization | 20 | 4.25 |

| Master | 79 | 16.77 |

| PhD | 1 | 0.21 |

| Organizational hierarchical levels | ||

| Board of directors | 54 | 11.46 |

| Chief executives | 35 | 7.43 |

| Supervisors and team leaders | 144 | 30.57 |

| Department support team | 184 | 39.07 |

| Operatives | 54 | 11.46 |

| Job area | ||

| Executive management | 55 | 11.68 |

| Sales and marketing | 71 | 15.07 |

| Production and operations | 74 | 15.71 |

| Administration and management | 111 | 23.57 |

| Human resources | 24 | 5.10 |

| Accounting and finance | 63 | 13.38 |

| Purchases and foreign trade | 10 | 2.12 |

| Logistics and distribution | 46 | 9.77 |

| Information technology | 17 | 3.61 |

- Note: n = 471.

3.3. Measures

DSE was measured using the Spanish adaptation of Ulfert-Blank and Schmidt’s [8] scale, previously validated in Ecuador by Paredes-Aguirre et al. [26, 27]. This instrument aligns with the competence areas defined in DigComp 2.1 framework of the European Commission and provides a structured assessment of confidence in managing digital technologies in professional contexts.

EH was assessed using the 24-item EH Scale (EHS) developed by Hong et al. [14] and validated in Spanish-speaking populations by Cansing et al. [38]. The EHS captures two related dimensions: PE and GOPs. PE reflects individuals’ perceived control over their career outcomes and comprises three subdimensions: self-worth, which refers to belief in one’s value and potential in the labor market; self-perceived capability, defined as confidence in one’s ability to succeed professionally; and future outlook, which represents optimism about career opportunities. GOP refers to an individual’s capacity to plan and pursue strategies for career development and includes self-motivation, or the internal drive for professional growth; utilization of skills and resources, which captures how individuals apply their competencies to enhance employability; and goal orientation, defined as a sustained focus on achieving career goals.

To explore differences across organizational hierarchical levels, participants were grouped into three categories based on their self-reported occupational roles. Senior executives include individuals in the Board or Chief Executive roles. The middle managers comprised supervisors, coordinators, and team leaders. Operational-level staff refers to employees in support or execution-oriented positions who do not hold formal leadership responsibilities.

3.4. Data Analysis

To assess the factorial validity and dimensionality of the research model, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using partial least squares (PLSs) [80]. Model fit was evaluated using the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) [81] and normed fit index (NFI) [82]. Internal consistency and convergent validity were examined using Cronbach’s alpha (α), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) [83].

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion (1981) and AVE values were compared with interconstruct correlations. All analyses were conducted using the SmartPLS version 4. PLSs structural equation modeling (PLSs-SEM) was used to test the proposed hypotheses. In addition, a MGA was performed to examine whether the relationships between DSE and the two EH dimensions differ across organizational hierarchical levels. This allowed us to test the differences between the three organizational hierarchical levels in the structural model.

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of Common Method Bias and Nonresponse Bias

To assess the common method bias in the PLS-SEM model, collinearity diagnostics were conducted following Hair et al. [80] and Kock [84]. No indications of problematic collinearity were detected, as the variance inflation factor (VIF) values for all indicators remained below the recommended threshold of 5, suggesting that common method bias was not a concern in this model.

Nonresponse bias was examined by analyzing the response rate and the use of multiple imputation techniques. The final response rate was 68.66%, which exceeded the benchmark for adequate survey-based studies [85]. Furthermore, multiple imputation analysis showed no statistically significant differences in the main study variables between early and late respondents, indicating that nonresponse bias is unlikely to have affected the results [86].

4.2. CFA and Reliability

CFA was conducted to assess the dimensionality of the study variables using PLSs-SEM. The model showed acceptable fit indices (SRMR = 0.070; NFI = 0.871), indicating acceptable model fit [82, 87]. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α), CR, and AVE. Thresholds were set at 0.60 for α and CR [88, 89] and 0.4 for AVE [90]. All indicators met the reliability criteria, as summarized in Table 2.

| Construct | α (95% CI) | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital self-efficacy (DSE) | 0.930 | 0.937 | 0.417 |

| Psychological empowerment (PE) | 0.899 | 0.918 | 0.501 |

| Goal-oriented pathways (GOP) | 0.965 | 0.969 | 0.726 |

Convergent validity was evaluated using AVE, with most latent variables exceeding the minimum recommended value. Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, which compares the squared root of AVE with interconstruct correlations [91]. While some correlations between the subdimensions of the EHS were high and the global constructs PE and GOP did not fully meet the Fornell–Larcker discriminant threshold, prior content validity testing conducted during the Ecuadorian adaptation [92] confirmed the distinction between these two dimensions. This justification aligns with previous psychometric practices in adaptation studies, where theoretical distinctiveness supports construct validity despite empirical overlap [93]. Table 3 shows the interconstruct correlation matrix used to assess the discriminant validity.

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSE-CSE (1) | 0.810 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| DSE-DSE (2) | 0.533 | 0.855 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| DSE (3) | 0.817 | 0.721 | 0.646 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| PE-FO (4) | 0.298 | 0.120 | 0.306 | 0.687 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| GOP-GO (5) | 0.303 | 0.162 | 0.349 | 0.729 | 0.869 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| GOP (6) | 0.335 | 0.152 | 0.367 | 0.738 | 0.936 | 0.852 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| DSE-ISE (7) | 0.685 | 0.416 | 0.773 | 0.330 | 0.368 | 0.388 | 0.856 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| DSE-PSE (8) | 0.478 | 0.548 | 0.805 | 0.215 | 0.248 | 0.249 | 0.462 | 0.839 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| PE (9) | 0.324 | 0.080 | 0.302 | 0.830 | 0.736 | 0.788 | 0.367 | 0.178 | 0.708 | — | — | — | — | — |

| DSE-SSE (10) | 0.523 | 0.459 | 0.793 | 0.214 | 0.291 | 0.320 | 0.547 | 0.570 | 0.227 | 0.806 | — | — | — | — |

| GOP-SM (11) | 0.307 | 0.126 | 0.329 | 0.726 | 0.841 | 0.949 | 0.347 | 0.221 | 0.750 | 0.294 | 0.911 | — | — | — |

| PE-SPC (12) | 0.318 | 0.086 | 0.292 | 0.730 | 0.702 | 0.763 | 0.337 | 0.170 | 0.945 | 0.229 | 0.726 | 0.847 | — | — |

| PE-SW (13) | 0.260 | 0.022 | 0.228 | 0.600 | 0.576 | 0.633 | 0.324 | 0.113 | 0.900 | 0.172 | 0.589 | 0.768 | 0.825 | — |

| GOP-USR (14) | 0.336 | 0.144 | 0.361 | 0.642 | 0.825 | 0.946 | 0.383 | 0.236 | 0.745 | 0.321 | 0.845 | 0.732 | 0.625 | 0.927 |

4.3. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

The hypotheses were tested using PLSs-SEM. The results indicated a significant positive relationship between DSE and both dimensions of EH across the full sample and across the three organizational hierarchical levels.

In the full sample, DSE was positively associated with PE (β = 0.394, p < 0.001) and GOPs (β = 0.343, p < 0.001), supporting Hypotheses H1 and H2. When analyzing the organizational levels separately, the relationship between DSE and PE remained significant in all groups. The strongest association was found among senior executives (β = 0.528, p < 0.001), followed by operational-level staff (β = 0.419, p < 0.001), whereas middle managers showed a weaker yet significant effect (β = 0.252, p = 0.007).

A similar pattern was observed for the relationship between the DSE and GOPs. The effect was strongest among senior executives (β = 0.463, p < 0.001), middle managers (β = 0.313, p = 0.001), and operational-level staff (β = 0.341, p < 0.001). These results provide preliminary support for the moderating role of organizational hierarchy in how digital confidence translates into employability-related outcomes. A detailed summary of the hypothesis testing is presented in Table 4.

| Hypothesis | Full sample | Senior executive’s positions | Middle managers positions |

Operational level positions |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 471) | (n = 89) | (n = 144) | (n = 238) | ||

| Standardized coefficients | |||||

| H1 | DSE→PE | 0.394 ∗∗∗ | 0.528 ∗∗∗ | 0.252 ∗∗ | 0.419 ∗∗∗ |

| H2 | DSE→GOP | 0.343 ∗∗∗ | 0.463 ∗∗∗ | 0.313 ∗∗∗ | 0.341 ∗∗∗ |

- Abrreviation: ns, not significant.

- ∗p < 0.05.

- ∗∗p < 0.01.

- ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

4.4. MGA Across Organizational Hierarchical Levels

To examine whether the structural relationships between DSE and the dimensions of EH varied across organizational hierarchical levels, a MGA was conducted. Following the recommendations of Cheah et al. [94], the analysis included both a permutation-based approach and Bootstrapped MGA, implemented using SmartPLS version 4. Prior to comparing path coefficients, the measurement invariance of composite models (MICOM) procedure was applied to test the configural and compositional invariance. The results confirmed that the measurement structure was consistent across groups.

Given the directional nature of the hypotheses, one-tailed significance tests were applied to assess between-group differences in the path coefficients, following standard practice in hypothesis-driven MGA. The analysis showed that the relationship between DSE and GOPs was significantly stronger among senior executives than middle managers (Δβ = 0.276, p = 0.004, one-tailed; p = 0.008, two-tailed). The difference between senior executives and operational-level staff members was not statistically significant (Δβ = 0.109, p = 0.104, one-tailed; p = 0.207, two-tailed). Regarding the relationship between DSE and PE, no statistically significant differences were found across groups (Δβ senior–middle = 0.150, p = 0.083; Δβ senior–operational = 0.122, p = 0.093).

These findings suggest that the influence of DSE on career planning and strategy formulation is stronger in higher organizational roles. In contrast, the relationship between DSE and perceived control over career outcomes remained consistent regardless of the position held. Table 5 presents the detailed results of the MGA.

| Path | Difference (high–middle) | Difference (high–low) | Difference (middle–low) | One-tailed p-value (high vs. middle) | One-tailed p-value (high vs. low) | Two-tailed p-value (high vs. middle) | Two-tailed p-value (high vs. low) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSE → GOP | 0.276 | 0.109 | −0.167 | 0.004 ∗∗ | 0.104 | 0.008 ∗∗ | 0.207 |

| DSE → PE | 0.150 | 0.122 | −0.028 | 0.083 | 0.093 | 0.167 | 0.186 |

- Abbreviation: ns, not significant.

- ∗p < 0.05.

- ∗∗p < 0.01.

- ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

5. Discussion and Conclusion Remarks

5.1. Main Findings

This study contributes to the literature on DSE and employability by demonstrating that DSE significantly predicts both dimensions of EH: PE and GOPs. Grounded in SCT [28, 62, 63], these findings support the idea that beliefs about one’s digital competence shape motivation and behavior in career development. Participants with high DSE reported a greater sense of control over their career outcomes and were more likely to engage in proactive planning and skill development. This finding reinforces the role of DSE as a psychological resource relevant to employability.

These findings are consistent with research on career self-efficacy and its influence on job-related motivation, persistence, and adaptability [67, 68]. However, this study extends prior work by linking DSE to broader psychological constructs that influence how individuals perceive their employability. The results showed that the relationship between DSE and PE was slightly stronger than its link with GOP. This suggests that while digital confidence contributes to a sense of control and empowerment, its influence on strategic career planning may also depend on contextual variables, such as access to training, managerial support, or sector-specific demands.

The MGA revealed variations in the strength of these relationships across organizational levels. The association between DSE and GOP was significantly stronger among senior executives than middle managers. This pattern implies that individuals in higher positions may benefit from greater autonomy and access to career resources, which enhances their ability to act with digital confidence when planning their careers. Middle managers and operational-level staff showed weaker effects, indicating that organizational constraints may moderate their capacity to translate DSE into goal-oriented behaviors. This asymmetry suggests a potential limitation in the generalizability of the GOP pathway because its effectiveness may depend on structural conditions that are not equally available to all roles.

By contrast, the relationship between DSE and PE was consistent across all organizational levels. This suggests that digital confidence contributes to feelings of control and PE independent of one’s hierarchical position. The stability of this association highlights that PE may be a foundational element of employability in a digital context.

These findings challenge traditional views of employability that emphasize external conditions or purely technical skills [36, 37]. Self-perception of digital ability appears to be critical in shaping career confidence, aligning with recent evidence that DSE can be a stronger predictor of adaptability than technical proficiency alone [11]. This perspective supports the inclusion of DSE in the updated employability models.

Overall, the study demonstrates that DSE is not only associated with competence but also with psychological dimensions relevant to navigating the digital labor market. As workplaces become increasingly reliant on technology, employability frameworks must consider not only what individuals can do with digital tools but also how confident they feel in their ability to adapt, learn, and grow in digital environments.

5.2. Practical Implications

The findings highlight the importance of fostering DSE as a means of strengthening individuals’ perceptions of employability. Beyond developing digital skills, organizations and training programmes should address the psychological components of digital readiness. Confidence in applying technology plays a central role in how employees manage career-related demands and adapt to digital transformations.

For organizations, DSE can be enhanced by integrating digital mentoring, practical technology workshops, and structured upskilling initiatives into employee development programs. These approaches can increase employees’ sense of competence and autonomy in navigating technological changes. Given that the relationship between DSE and goal-oriented behavior was stronger among senior executives, interventions for middle managers and operational-level staff should focus on reducing structural barriers and increasing access to career-planning resources. Human Resources professionals should be aware that employees with lower DSE may face higher stress and disengagement during digital transitions and may benefit from targeted support.

For higher education institutions, DSE development should be incorporated as a transversal competence into their curricula. Exposing students to real-world digital tools and requiring active digital problem solving can help them build confidence before entering the labor market. Since this study was based on data from professionals already active in the workforce, the implications are particularly relevant for educational programs aimed at supporting career mobility and resilience among early- and mid-career professionals.

As digital demands continue to increase across industries, initiatives that enhance both digital skills and confidence in their applications may improve long-term adaptability, motivation, and career sustainability.

5.3. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, data were collected through self-report instruments, which may have introduced response bias. Participants may have overestimated or underestimated their DSE or employability perceptions depending on their confidence levels. Future research should combine self-reports with objective assessments of digital competence to obtain a more robust understanding of these constructs.

Second, the sample was drawn from formally employed individuals in Ecuador, primarily working in administrative, technical, or operational roles within organizations. This may limit the generalizability of the findings. The observed associations between DSE and EH may differ across industries, job functions, organizational cultures, or national contexts. Further studies should explore whether similar patterns emerge in other countries and among professionals at different career stages.

Third, the cross-sectional design limits causal inferences. Although DSE was found to predict both PE and GOPs, longitudinal research is needed to examine how changes in DSE over time influence employability perceptions and career outcomes. Experimental studies could also test the effectiveness of targeted interventions to enhance DSE and assess their impact on employment behavior.

Finally, although the overall model showed acceptable fit, the NFI was slightly below the conventional threshold. In addition, PE and GOPs showed partial discriminant validity. Although previous validation studies support their conceptual distinction, further refinement of these constructs may improve model fit in future applications. Moreover, while the MGA revealed significant differences in the DSE–GOP relationship across organizational levels, the underlying mechanisms behind this variation remain unclear. Future research should examine how organizational resources, autonomy, or career structures interact with DSE to influence employability outcomes.

5.4. Future Research Directions

This study underscores the potential of EH as a valuable construct in employability research. Although EH has been widely examined in the context of social work, its application in disciplines, such as human resources, organizational behavior, and education, remains limited. Future studies could investigate how EH relates to other constructs such as career adaptability, job satisfaction, and work engagement to better understand its contribution to professional development.

Further research is needed to explore how contextual factors shape the relationship between DSE and EH. Elements such as workplace support, access to digital learning opportunities, and sector-specific technological requirements may moderate how DSE translates into empowerment and goal-setting behaviors. Identifying these moderators could inform the design of targeted interventions that address the needs of professionals at different organizational levels.

Longitudinal studies should examine how DSE influences career trajectories. Early-career professionals may rely on DSE to secure employment, whereas mid-career employees may need to adapt to evolving digital demands. Senior professionals may use their digital confidence to guide strategic planning and lead to technological change. These patterns could offer insights into how DSE function across the stages of career development.

Beyond organizational hierarchy, future research should examine whether the effects of DSE on employability differ across sectors. Highly digitalized industries may offer environments that reinforce the value of DSE, while more traditional sectors may require deliberate efforts to support digital skill development. Comparative studies across sectors could help to clarify how the digital context shapes the impact of DSE on employability-related outcomes.

Finally, future research should consider how perceptions of DSE and employability evolve in response to emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence and automation. As digital skills continue to be integrated into workplace roles, identifying mechanisms that help individuals navigate technological change is essential for advancing both theory and practice in digital workforce development.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study was funded by Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral and Universidad ECOTEC.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.