Individual and Contextual Factors Associated With the Prevention of Corruption: A Qualitative Study Among Iranian Public Employees

Abstract

Background: Little research has been done to identify the individual-level factors contributing to the prevention of administrative corruption. Specifically, Iranian public employees are an understudied population in terms of individual and contextual factors that contribute to the prevention of administrative corruption. This study aimed to identify the perception of public servants about the psychosocial factors that facilitate the prevention of corruption.

Method: Data were collected using semistructured interviews with 14 individuals working in public sector departments or agencies in Tehran.

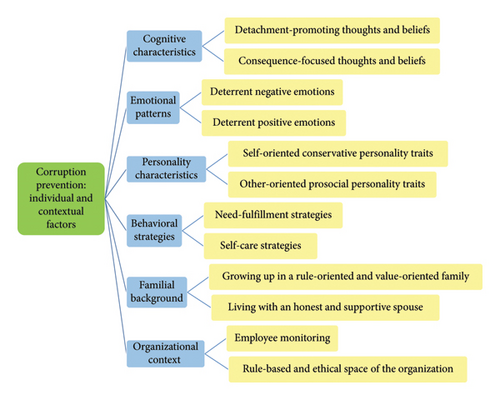

Results: Six main themes emerged from the data: cognitive characteristics (including “detachment-promoting thoughts and beliefs” and “consequence-focused thoughts and beliefs”), emotional patterns (including “deterrent negative emotions” and “deterrent positive emotions”), personality characteristics (including “self-oriented conservative personality traits” and “other-oriented prosocial personality traits”), behavioral strategies (including “need-fulfillment strategies” and “self-care strategies”), familial background (including “growing up in a rule-oriented and value-oriented family” and “living with an honest and supportive spouse”), and organizational context (including “employee monitoring” and “rule-based and ethical space of the organization”).

Conclusion: The study reveals some psychological and contextual factors that could be involved in preventing administrative corruption in Iran. These factors can be taken into consideration when designing preventive measures and policies aimed at reducing corrupt behaviors in public agents and promoting ethics in public service.

1. Introduction

Corruption has been widely recognized as a major obstacle to development and sustainability. The study of corruption in government, and efforts to prevent or contain it, lies at the very core of modern public administration [1]. Prioritizing corruption prevention over merely addressing it after the fact is crucial for maintaining the integrity and functionality of institutions. Preventive measures help to establish a culture of transparency and accountability, reducing the opportunities for corrupt practices to take root. According to the U.S. Strategy on Countering Corruption, effective prevention can mitigate the extensive social, economic, and political damage caused by corruption, which includes undermining public trust and exacerbating inequality [2]. This study seeks to examine the perceptions of Iranian public employees regarding the individual and contextual factors that enable them to avoid engaging in administrative corruption within their professional experiences.

Administrative corruption (also called petty corruption and bureaucratic corruption) occurs when an official or public servant uses official capacities for personal purposes and benefits. The authors in the field [1, 3, 4] have mentioned several examples of administrative corruption practices: among others, collusion (an agreement between two or more people that is made with the purpose of deception, and fraud of people’s legal rights and obtaining unfair benefits), bribery and kickback (receiving gifts, money, sexual favors, political benefits, etc., in exchange for discriminatory behavior or disclosure of secrets), embezzlement (where a person illegally appropriates funds or property), graft (a type of political corruption in which politicians, by abusing their position and power, divert the budgets approved for certain projects in a way that maximizes benefits for their relatives), extortion (including threats of violence or illegal imprisonment or even threats to reveal a person’s previous crimes), influence peddling (a person’s abuse of their influence in the government entities and their familiarity with government officials to obtain discriminatory treatment for the personal benefit of a third party), networking (the networker tries to establish friendly and close relationships with employers, employee selection boards, etc., hoping to use these relationships to influence their decision to hire an unqualified job applicant), nepotism (favoritism; injustice, discrimination, and substitution of a relationship instead of rules in which influence is exerted in favor of one of the relatives or friends), selling confidential information of the organization to others (transferring classified information outside the organization in exchange for personal benefits), and patronage (supporting subordinates in order to gain their support in the future).

Several causes and factors for the commission of administrative corruption have been mentioned. Dimant and Tosato [5], in their study, identified the causes of corruption as follows: greed for money and power, the existence of a monopolized economy, weak civil participation, very little transparency, cumbersome bureaucracy, low press freedom, insufficient integration into the global economic system, poverty, low level of education, and absence of job rotation policy. Some researchers have also mentioned the mechanisms and legal loopholes that make possible the occurrence of administrative corruption and money laundering [6]. Klitgaard [7] puts forward the hypothesis that administrative corruption will occur if the benefit is greater than the punishment or fine multiplied by the probability of arrest and trial.

A line of research has approached the determinants of corruption focusing on the individual and psychosocial factors that influence the commission of corruption. This approach argues that despite conflict of interests, lack of transparency, problems in the law, and the like, corruption is ultimately done by a human agent and based on his/her thoughts, decisions, and actions. In the following, some theoretical and research efforts in this field have been reviewed.

Gender has been one of the individual-level factors investigated in the field of corruption. In countries where more women are involved in governance and workforce, corruption is becoming a less serious problem [8, 9]. However, this correlation does not necessarily imply causation [10]. Some countries even followed this hypothesis in practice. For example, in 1998, Peru’s traffic police was all women, and in 2003, the Mexican Customs Service launched an all-female anti-graft force [11]. Han [12] examined the effect of individual-level determinants on the justifiability of corruption by South Asian people and their tolerance toward corruption, showing that relatively younger and/or less educated and/or collectivistic people are more likely to justify corruption, while older and/or more educated and/or individualistic people are less likely to legitimize it.

People want to maximize their material interests; at the same time, they want to see themselves as ethical actors. Thus, there is a balance between maximizing personal gain and maintaining a view of oneself as a moral person. Köbis et al. [13] have proposed two metaphorical arguments in this regard: the “slippery slope” and the “steep cliff.” In the “slippery slope” hypothesis of corrupt behavior, small acts and small crimes gradually lead to bigger acts. That is, corruption is likened to a “slope” that when a person starts it, he/she gradually speeds up and becomes more and more corrupt. The reason is that most people consider themselves to be “right” in general, and if they do something wrong, they feel like they are going against their identity. Therefore, it takes time for them to become a corrupt person. On the other side of this spectrum (steep cliff), there are so-called “golden opportunity” moments, whereby a single event is tempting by itself; it means that people deal with one-time and big corruptions more easily than small corruptions. Of course, the result of the research by Köbis et al. [13] indicates that the probability that people unexpectedly do something extremely unethical is more than that they are prepared for it, so the possibility of being thrown off the “steep cliff” is higher. Most people believe that they are moral people, so if they do something unethical, they have to adapt it to their identity. Psychologically, it is easier to justify a mistake than mistakes repeated several times. One-off mistakes may create less tension between being ethical, on the one hand, and enjoying the benefits of cheating, on the other. Probably, the person does not consider what was done once as a true indicator of their character. However, in a slippery slope situation, one has to deal with successive immoralities.

Moral compensation theory claims that moral behavior is motivated by the desire to maintain one’s self-image. According to this theory, people compensate to restore their self-image, which is based on the perception of their morality [14]. Concerning compensatory behavior, this theory posits that an initial unethical act threatens a person’s self-worth and subsequently motivates them to pursue a restorative moral act. For example, a person negotiates with himself; she/he donates some money to charity and gives himself/herself the freedom to be more relaxed about something else.

The traditional deterrence-based approach, which is based on rationality, emphasizes the role of controlling and deterring factors in preventing corruption. Followers of this approach believe that government agents consider corruption as a result of rational calculations of costs and profits (cost-benefit analysis). That is, decision makers are rational beings who try to further their interests in a world of scarce resources, and they analyze the cost and benefit of the money or potential power gained versus the risk of getting caught, and even moral torture before making decisions. Lianju and Luyan [15] demonstrated that punishing corruption after it has occurred is not a good way to prevent it from happening in the future, and such corrupt practices are only stopped when their risk is much greater than their potential reward.

Manara et al. [16] explored the intra-individual cognitive-motivational decision-making processes underlying corruption among individuals sentenced for corruption. They intended to identify the specific decision-making stages that people engaged in before deciding to behave corruptly. For most of the typical forms of corruption, their qualitative data support the idea that the process leading to corruption resembles general decision-making models and proceeds through different stages, including the identification of a problem and goal formation, information search, and evaluation of this information. However, their results highlight that corruption may involve a more elaborate decision-making process than previously considered in models of unethical and immoral decision making. In the domain of goals, the informants mentioned not only their personal and organizational goals but also several social goals, including helping farmers, improving public facilities, and aiding the general public. Therefore, they showed that corruption, generally considered immoral behavior used to advance personal goals, can also be a means of achieving prosocial and morally sound goals.

However, Rangone [17] believes that some hidden cognitive factors are involved in the corruption process that should be considered. Rationality has a limited capacity to assess risks and possibilities; it is usually overly optimistic and driven by other biases and heuristics. Cognitive science challenges the hypothesis that people are rational. In the real world, people often do not want to rethink their decisions; they care more about current losses than future gains. Dupuy and Neset [18] also showed that cognitive processes such as justifying narratives (rationalization defense mechanism) are effective in committing corruption.

Othman et al. [19] presented a model of factors influencing administrative corruption based on a qualitative study in Malaysia. This model was designed based on research conducted among experts, representatives of government agencies, and senior public sector employees. In this model, the three main factors of administrative corruption are as follows. (1) Power: This dimension refers to the ability to influence and the ability to exert will, and this originates from the job position in which the person is appointed. (2) Opportunity: Opportunity alone cannot give people self-confidence, but when it is combined with legal power, the amount and frequency of corruption increases due to high self-confidence in committing the act. (3) Moral impurity: Another reason why people commit corrupt acts is the lack of moral values and moral commitment. Farhadinejad [20] also mentioned the low level of adherence to ethics as one of the psychological factors of administrative corruption. Tian [21] showed that there is a significant relationship between the ethical philosophy of Chinese business managers and illegal payments, such as bribes. It is argued that moral relativism has a positive correlation with bribery, and to prevent corruption, absolute ethics should be expanded.

The low level of faith and religiosity is mentioned among the psychological factors of administrative corruption [19, 20]. Khadem and Hemayatkhah [22] surveyed 200 employees of Jahrom University of Medical Sciences and showed that religiosity is a predictor of work ethics. The result of their research indicated that with increasing levels of the experiential dimension of religiosity, organizational ethics increased, and organizational corruption decreased.

High greed has also been found as one of the causes and roots of corruption [5, 19, 20, 22–24]. Not all those who commit administrative corruption are in so much trouble in terms of livelihood that they have to surrender to it, but in some cases people engage in administrative corruption because of extravagance and ambition. The low level of work ethic and conscientiousness has also been identified as one of the factors leading to administrative corruption [20, 25]. In addition, the high degree of risk-taking and lack of fear of deterrent punishments are among the psychological factors [20, 24]. Zhao et al. [26] examined the association between the Dark Triad of personality (i.e., Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy) and corruption through a mediator—belief in good luck. The results indicated that while the Dark Triad of personality positively predicted bribe-offering intention, it was mediated by the belief in good luck in gain-seeking. Their findings also revealed that the Dark Triad of personality was positively related to bribe-taking intention; the link between narcissism and bribe-taking intention and that between psychopathy and bribe-taking intention were mediated by the belief in good luck in penalty avoidance. This research extended previous research by providing evidence that belief in good luck can be one of the reasons explaining why individuals with Dark Triad are more likely to engage in corruption regardless of the potential outcomes.

Contextual and situational factors have also been subject of research inquiries. Manara et al. [16] demonstrated that contextual factors (e.g., task type, time pressure, and hierarchical structures) can determine whether individuals engage in rational or intuitive corruption and dishonesty. Furthermore, an important environmental factor in the appearance of corruption, especially in private organizations, is the criminal nature of the organization itself, which is caused by the profit motive and free market competition. The economic motivations of the organization can cause employees to behave unethically and sometimes illegally for the benefit of their employers, and they benefit indirectly as well [27]. The receipt of salaries depends on the persistence of corrupt practices within organization. Campbell and Göritz [28] investigated the underlying assumptions, core values, and norms in organizations where corruption is most prevalent. In this study, content analysis was conducted on interviews with 14 independent experts about their experience in corrupt organizations. They found that there is an obvious assumption in the culture of such organizations: “The end justifies the means.” An important norm in these organizations is the punishment of deviant (i.e., noncorrupt) behavior. The corrupt people in the organization not only have “ethical blindness” but also tend to protect the “social cocoon” they have built by severely punishing those members who do not want to join in breaking the law. As long as the cocoon rejects outside ideas, the group remains corrupt. On the other hand, in a group environment, newcomers tend to change their personality to adapt to the group identity and be accepted into the group.

Recently, the role of family of origin, as a context, has also been emphasized in anti-corruption research. For example, Nugroho et al. [29] claim that if anti-corruption campaigns are to be effective, mothers must be involved in anti-corruption education, especially for children; they contend that the process of character-building will require early inculcation of anti-corruption ideals to prevent the manifestation of corrupt behavior in the future, and the creation of the virtual community character education will likely help prevent future corruption.

As mentioned above, among other predictors of corruption, several individual and contextual factors can also cause employees to engage in administrative corruption. However, little research has yet been done to identify the individual and contextual factors contributing to the prevention of administrative corruption. Specifically, to our knowledge, there is a paucity of research in this regard among Iranian public servants. It should be noted that although administrative corruption exists in most parts of the world, especially in developing countries, it is a serious problem in Iran. The Islamic Republic of Iran is one of the countries with a high rate of administrative corruption [1, 30, 31]. In its 2023 report, Transparency International, considering the Corruption Perception Index (CPI), has ranked Iran 149th among 180 countries in terms of the spread of financial corruption, and this is Iran’s worst ranking position in recent years [32].

This Iranian study seeks to tackle this gap by qualitatively exploring the individual and contextual factors associated with administrative corruption avoidance. The research question we set out to answer is “what is the perception of public sector employees about the psychological/contextual factors potentially involved in the prevention of administrative corruption?”

Using a constructivist research paradigm and a qualitative approach, our inquiry helps view the phenomenon from the perspective of the actors and through an intrapsychic lens. In our study, we selected individuals who were not involved in corrupt activities as our research sample. This approach contrasts with previous studies that included participants who were perpetrators of corruption. By focusing on nonperpetrators, our research takes a positive and preventive perspective, which we believe is innovative and enhances the value of our study.

In summary, this study aims to explore the perception of Iranian public employees about the individual and contextual factors that are associated with avoidance of corruption in their personal work experience. By addressing micro-level protective factors, we aim to contribute to research on the multifaceted and complex puzzle of corruption prevention.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was qualitative in design, and we used semistructured interviews to collect data.

2.1. Sample

The participants included 14 public employees in Tehran, who were selected using the convenience sampling method (volunteer sampling type) and through posting a call on social media for inviting the potential research participants. First, a conversation was held with potential participants (20 persons); those who met the inclusion criteria (16 persons) were selected. The process of sampling and data collection continued until the conceptual saturation of the categories (interview with 14 persons). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) employment in one of the public sector departments or agencies in Tehran; (2) declaration of having experience of not committing instances of administrative corruption in cases where there was an opportunity for it; and (3) at least five years of work experience. Table 1 shows the participants′ demographics.

| # | Gender | Age | Education | Marital status | Work experience (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Man | 40 | Bachelor’s | Married | 15 |

| 2 | Woman | 35 | Master’s | Single | 6 |

| 3 | Man | 32 | Bachelor’s | Single | 8 |

| 4 | Man | 41 | Doctorate | Married | 10 |

| 5 | Woman | 44 | Bachelor’s | Divorced | 12 |

| 6 | Woman | 32 | Master’s | Single | 5 |

| 7 | Man | 49 | Bachelor’s | Married | 25 |

| 8 | Man | 51 | Master’s | Divorced | 26 |

| 9 | Man | 39 | Master’s | Married | 9 |

| 10 | Man | 38 | Master’s | Single | 6 |

| 11 | Man | 42 | Doctorate | Married | 13 |

| 12 | Woman | 47 | Bachelor’s | Married | 21 |

| 13 | Man | 40 | Master’s | Single | 12 |

| 14 | Man | 42 | Master’s | Divorced | 9 |

According to Table 1, 10 of the study participants (71%) were men and four of them (29%) were women. The average age of these participants was 40.85 years. Seven informants (50%) had a master’s degree, five (36%) had a bachelor’s degree, and two (14%) had a PhD degree. Six of the participants (43%) were married, five (36%) were single, and three (21%) were divorced. The average work experience of the respondents was 12.64 years.

2.2. Procedure

As this qualitative study is descriptive and explanatory, the focus has been on giving descriptions of the respondents′ experiences, while at the same time, the researcher’s preunderstanding and personal involvement have been toned down. To this end, semistructured interviews were used for data collection. This data gathering method expands not only our knowledge but also our understanding of the subjective dynamics of corruption prevention. Semistructured interviews allow researchers to adjust the interview guide based on participants′ responses, delve deeper into specific topics, and follow up on interesting points. This adaptability ensures that relevant information is captured. During semistructured interviews, unlike structured interviews, participants more likely feel heard and valued, which enhances rapport and encourages openness. This approach is especially valuable when studying sensitive topics like corruption.

The questions asked from the participants were based on an interview guide (see Table 2). The interviewer also used clarifying questions, such as “Could you tell me more?” It should be mentioned that the central and supplementary questions of the interview protocol were formulated based on the research objectives as well as the research literature; after obtaining the opinions of two research experts in behavioral and social sciences, the interview guide was modified and finalized. Data collection was carried out from November 2022 to March 2023. The interviews were conducted in Persian and by a Ph.D. student in Counseling, at the time of the participants′ choice and via a video or audio call (via Skype, Google Meet, or phone). Each interview took approximately 45–90 min (average duration 50 min per participant). Due to the sensitivity of the subject and to gain trust, we did not audio-record the interviews, and the interviews were instantly written verbatim on paper. To create a safe atmosphere for the respondents in which they could openly and honestly represent their experiences, we ensured their privacy and confidentiality during data collection.

|

|

2.3. Data Analysis

Data were inductively analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) [33]. RTA facilitates a comprehensive understanding of participants′ experiences, perspectives, and the sociocultural contexts influencing them. Thus, we believe it is relevant for categorizing the individual and contextual elements reported by informants for corruption avoidance. RTA helps to see the bigger picture by grouping similar ideas and experiences into distinct themes. We did not intend to fit our findings into a predetermined theoretical mold; using RTA, we followed this inductive approach, allowing the themes to emerge naturally from the data rather than forcing them into pre-existing categories.

First, we repeatedly read the interview transcripts, searching for concepts. Then, we coded the data and categorized the concepts that were conceptually related. The categories and subcategories were linked to related codes in the material. The research analysis was an iterative and reflexive undertaking. After four iterations of coding, discussion, and refinement, a high level of inter-coder agreement was achieved (about 90%). Finally, we found six main themes and described them. Following the completion of the analysis process, we identified the fundamental characteristics of the psycho-contextual factors that are associated with informants’ avoidance of administrative corruption. After all interviews had been analyzed, the main citations (participant responses and statements) for each category were translated into English by the researchers.

2.4. Trustworthiness

To ensure the trustworthiness of the present study, the criteria suggested by Lincoln and Guba [34] were followed. We took into account the diversity in participants′ age, gender, occupation, and education. Written notes were taken during the interviews, contributing to the quality of the data. A peer examination was carried out by three experts who verified the coding and categorization process. All research group members were involved in checking interview drafts and verifying all codes and categorizations.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

In this investigation, all the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were considered. The participation of the participants in this study was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from them. Additionally, prior to the interview, participants were assured of the anonymity of the information they provided. The interviewees had the right to withdraw the research at any time without any consequences to them. This study was also reviewed by the Research Ethics Committee of Allameh Tabataba’i University and was approved in terms of compliance with ethical guidelines for research involving human subjects (protocol code: IR.ATU.REC.1399.077).

3. Results

The results of thematic analysis led to the formation of six main themes: “cognitive characteristics,” “emotional patterns,” “personality characteristics,” “behavioral strategies,” “familial background,” and “organizational context.” These main themes are described below. Figure 1 presents an overview of our findings.

3.1. Cognitive Characteristics That Prevent Administrative Corruption

This main theme refers to thoughts and beliefs that are perceived by the person to help him/her refrain from committing corruption through considering themselves needless of the benefits from corruption or through considering its multifaceted consequences. Twelve participants (86%) endorsed this theme. In this main theme, two patterns (subthemes) were observed: “detachment-promoting thoughts and beliefs” and “consequence-focused thoughts and beliefs.”

Understandably, the economic pressure is high… but we sometimes fuel some of our problems and are not satisfied! Another thing that helps me is to compare my situation with my past and not with the situation of others… Some women are keeping up with the Joneses, and this comparison of themselves with others may cause them or their spouses to step on the wrong path and do deviant work in their jobs…

I often think that all people are experiencing this inflation and economic pressure, and it′s not just me. This calms the person down, and the person does not feel pressured to do something wrong…

One issue that I think is very effective is the reputation issue. I am very afraid of dishonor; it is very important to me what position and image I have in the minds of others, and to maintain this reputation, I am very careful about my decisions and behavior in the workplace… (Informant #14)

Just like glass when it is broken, it will not be the same glass as it was before, it cannot be repaired… When a person realizes that the damage they do to themselves and their society cannot be repaired and compensated, it becomes very scary to do it… (Participant #2)

I also believe in the importance of earning halal income. I don’t like to feed my baby with the food prepared from haram earning… (Participant #9)

I see God always present and watching and I believe that He is watching me and I should not upset and anger Him with my actions… (Respondent #12)

I may not do some religious activities and rituals, but God’s satisfaction is very important to me. Sometimes my working hours were over and I was not obliged to stay, but I stayed at work for an extra hour so that people’s work could be done. I had God’s satisfaction in mind (Interviewee #7)

I believe in the return of the results of actions to oneself; something like karma. It means whatever you do, you will get it. If you do something good, you will see… if you do something bad, it will happen to you. If I want to mislead the client or take a bribe from them, someone else will do the same to me or my family one day… (Participant #6)

The authenticity of my existence is important to me. What am I striving for in my job? To create a false self for myself? The one I don’t like? I don’t like my self-image to be black! (Participant #2)

Doing the right thing never means making a loss… It is not worth winning the world outside in return for losing the world inside… (Respondent #3)

My deviation and mistake have an erosive effect and I have to pay the psychological and time cost. I always have to justify myself and my conscience for that decision, and this takes away from me being in the moment and being calm… (Interviewee #2)

3.2. Emotional Patterns That Prevent Administrative Corruption

This main theme includes feelings that have a positive effect on the individual in preventing cases of administrative corruption. Ten participants (71%) endorsed this theme. In this theme, two patterns were observed: “deterrent negative emotions” and “deterrent positive emotions.”

Well, I am a religious person. One of the reasons for my divorce was the lack of certain obligations in my husband. Sometimes, when an unethical work situation occurs in our department, the feeling of fear of God and the fire of hell makes me not follow those paths…

There was once a situation where I could change a purchase invoice for my benefit. But I overcame this temptation and I felt like a hero that I won over my ego. This is a very good feeling and can help in similar cases. Of course, the important thing is that you are able to do something wrong, but you don′t do it… (Informant #3)

I like purity for itself. Purity has a special pleasure that cannot be described at all, and I don′t want this feeling to be damaged by doing fraudulent work…

3.3. Personality Characteristics That Prevent Administrative Corruption

This main theme implies distinctive personality traits in a person, which probably play a role in their tendency to refrain from engaging in corrupt affairs. This theme was endorsed by 13 participants (93%) and consists of two patterns: “self-oriented conservative personality traits” and “other-oriented prosocial personality traits.”

I am generally content and not very ambitious. I prefer a simple but calm life without struggling. That′s why I don′t look for wealth and… (Interviewee #1)

I obsess over things. I always make life difficult for others and myself and have strict standards. I judge everything with my standards and conscience. That’s why I don’t allow myself to violate my standards… (Participant #4)

Well, there are times when the situation that comes up is very tempting… I took advantage of a situation once years ago… maybe you can call it rent… but I’m a coward. Now, when I think that after all these years of civil service, I may be fired or tried because of extravagance, it is a bit scary. Some employees may do false invoicing or manipulate salaries and benefits, but I don’t think it’s worth the risk… I’m not a risk-taker! (Participant #8)

The inflation is indeed terrible and the economic pressure is very high, but the fact that I see a ray of hope for the future, that the situation will probably improve and our welfare will improve, makes the situation more bearable for me. I keep hope in myself and when I talk to my colleagues about economic issues, I give them hope too… I am generally a hopeful person and I try not to disturb my peace because of external issues so that I don’t have to do something unreasonable subsequently… (Respondent #7)

Administrative and economic corruption causes the most damage to the country and the people of the society. I am a very strong patriot. When we protest against the unfavorable economic situation in the country, we must do the right thing first. I try to do the right thing for Iran and its progress. Once, one of my close relatives asked me to do something to hire him, i.e., nepotism; and I answered him in a bad tone: “You, who are constantly nagging about the country′s issues and problems, why are you looking for cronyism?”… Someone who loves his/her country will never replace meritocracy with anything else… (Informant #11)

I always tell my colleagues that even a small piece of bad work is too much! I am very absolutist. I don’t understand those people who say ethics is relative. Some people say that there is no problem [being unethical] for one time, but I say that being ethical in family life and at work is a universal and absolute principle. Ethics is a vital thing to help humanity… (Participant #13)

The person in there who is harmed by my immorality is very similar to me. When I walk in his shoes, I see that’s me myself! (Participant #2)

3.4. Behavioral Strategies That Prevent Administrative Corruption

In difficult economic conditions, having a second job is one way. For example, instead of doing illegal work in my main job, I spent some more time and started a part-time business to cover the deficiencies in my life…

In my opinion, employment and working in civil service destroy a person from the inside out. It destroys creativity and dynamism. The employee, like a robot, goes in the morning and comes back in the evening for a month to get a salary at the end of the month, but in this way, he does not progress at all and then he may be forced to do unethical things. I had nothing to do with my main job, which is being a public employee, and I only looked at it as an entertainment. But, in parallel, I attended financial literacy and wealth-building courses, and through investment and professional trading in the national and international stock market, I no longer need the income of my main job…

Another thing that helped me was changing my job. I used to be in a branch where there was a cabal-like atmosphere and high group pressure. I also witnessed cases of illegal gratuities, bid rigging, etc. … I was sick of this. Later, with a thousand troubles, I got a transfer to a new place… if one gets out of that toxic environment and changes his job, he will finally build his life the way he wants… (Participant #1)

Maybe a long time ago, I sometimes did less work in my job, but later I learned from a psychological counselor to check, every night before going to sleep, to see if the things I did during the day were in line with my goals or not, and which things were good and useful. And which of them were bad and useless. I do the same thing with my work. I believe that when a person goes down the wrong path, his mistakes get bigger and bigger… The fact that I constantly monitor and evaluate myself makes me pay attention to my work and not act against ethics… (Informant #12)

I believe that human brain starts with little, but it is not satisfied with little. It becomes a habit! I am very aware of myself to see the same little thing as big for me and not do it. According to the famous proverb, an egg thief becomes a camel thief! [A Persian proverb equivalent to “(he) who steals an egg, steals a cow”]. When deciding on any action, I give myself more time to think, I am not in a hurry, and I think about these issues (Participant #2)

3.5. Familial Background That Prevents Administrative Corruption

In my family of origin, there were clear boundaries and a kind of hierarchy. My parents had carefully drawn the boundaries. Children did not have the right to interfere in the affairs of mom and dad, or, for example, we had to knock on the door to enter any room. You know, my brother and I learned to respect boundaries and privacy from childhood. In the organizational position I have, maybe if someone likes it, he can do something secretly… but I try to take care of the boundaries of my responsibility and professional commitment. Of course, it′s really difficult… (Informant #10)

In our family, there was a lot of emphasis on doing the right thing, and if we did moral or godly things in our childhood and adolescence, our father encouraged us. For example, we had learned from Mom and Dad that if we find money or a wallet on the street, it is not ours and it is a trust, and we must look for its owner or finally give it to a charity… (Interviewee #4)

My parents were a practical example of a moral life. They did not carry out the parenting and educating of children merely by words and orders. … They educated practically and they lived honestly and righteously. I think it was very important and effective… (Participant #14)

Of course, religious teachings and education in the family are very effective. My mother always told me to live like faithful and honorable people and try not to lie and do injustice to anyone. Sometimes I hear my mother’s voice in my head and I don’t forget honor and piety (Participant #6)

Sometimes, exploitation and utilitarianism are not all the fault of the individual but partly due to the pressures and the blames from the family. If someone′s wife constantly blames him and keeps telling him “Look at your so-and-so colleague who started working in your office at the same time as you, how much better his financial situation is now,” he will be under a lot of pressure. But my wife has always been a supporter and companion in financial problems, and I was not under such pressure… (Respondent #7)

My wife is very sensitive to right and wrong and she observes it herself. When we got married, we promised each other about earning halal income. If there is something that smells of corruption and immorality, I will not do it at all. Her face and the principles of our marital life immediately come before my eyes… Sometimes when I feel like someone is being discriminated against in a governmental organization, I feel very bad, but I try never to do these things myself…

3.6. Organizational Context That Prevents Administrative Corruption

In our organization, monitoring and surveillance of employees and workers′ activity are very strong. The senior managers check every case that we have approved very carefully, for example, to see whether we have approved the loan and mortgages for someone who does not meet the loan conditions… If you leave people alone, likely they will do whatever they can. But if there is a committed manager or a camera [CCTV] and microphone above each employee′s head, he will take extra care… (Informant #14)

Periodic monitoring in the organization is very important, but random monitoring is even more effective. It means that a person does not know when his performance status is going to be audited and so he is alert and careful about his decisions every moment. In our organization, sometimes these random and intrusive audits are done… (Participant #9)

The head of our office is a very committed, respectable, and honorable person himself. In my opinion, the honor of the manager of an office is a very important point and can affect all the personnel and office workers. When the manager is corrupt, it seems like it becomes permission for others to abuse their job position if they can, but when the manager is morally healthy, employees are probably more careful about their work…

The atmosphere of communication between the personnel at my workplace is serious and professional and I like it very much. In some other organizations, colleagues are too friendly and intimate. Some do these planned befriending and affection intentionally, and later they abuse this intimacy; if they do something wrong, their colleague or boss will more likely overlook it. To prevent corruption, one way is to have strict professional boundaries between people in the organization.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to identify the perception of Iranian public servants about individual and contextual factors that prevent administrative corruption. The results of data analysis led to the formation of six main themes: “cognitive characteristics,” “emotional patterns,” “personality characteristics,” “behavioral strategies,” “familial background,” and “organizational context.” Some of the findings are discussed and explained in detail below.

The study findings showed that consequence-focused thoughts and beliefs are associated with a reduction in administrative corruption. Belief in the need for authenticity and self-concept preservation, the belief in the irreparability of deviation in human existence, the belief that it is not worth winning the world outside in return for losing the world inside, and belief in the erosive effect of immorality on human existence were among these beliefs. These findings are in line with those of Dunning [14]. Moral compensation theory claims that moral behavior is motivated by the desire to maintain one’s self-image. According to this theory, people compensate to restore their self-image, which is based on the perception of their morality [14]. Concerning compensatory behavior, this theory posits that an initial unethical act jeopardizes a person’s self-worth and subsequently motivates them to pursue a restorative moral act. In the current study, participants believed in the necessity of authenticity and preservation of self-concept, as well as the irreparable nature of deviation in human existence, and this probably caused them to avoid falling into the abyss of corruption.

Thinking about the consequences of one’s actions on others and believing in the importance of reputation and social status were other indicators of consequence-focused thoughts and beliefs. This finding is in line with the research results of Lianju and Luyan [15]. According to the individual rationality theory, the decision to commit corruption is affected by the result of rational calculations of costs and benefits [35, 36]. Such corrupt practices are only stopped when their perceived risk outweighs their potential reward (i.e., benefits of engaging in corrupt undertakings) [15]. The participants in the present study, probably influenced by factors such as thinking about the consequences of their actions on others and considering their reputation and social status, have kept in mind the consequences of committing corruption and have considered them when evaluating their decisions and actions.

Belief in the necessity of halal earning, belief in God’s supervision and omnipresence, and belief in the positive effect of honesty on obtaining God’s satisfaction were also found as signs of consequence-focused thoughts and beliefs in this study, which in a way represent faith in God and having divine piety. This finding is consistent with Othman et al. [19], Khadem and Hemayatkhah [37], and Farhadinejad [20] who identified the low level of faith as one of the psychological factors of administrative corruption. It seems that authentic adherence to religion likely leads to the creation of expectations related to religious roles and may facilitate the emergence of moral awareness and judgment and, consequently, moral conduct and moral behaviors.

The belief that the result of the action will return to the person was another consequence-focused belief associated with the prevention of administrative corruption that was identified in our investigation. To the authors′ knowledge, to date, no findings similar to this have been mentioned in previous studies. The Iranian-Islamic cultural background of the participants in this study can be used to explain this finding. Iranian people are always proud of their rich literature, love Iranian poets, and usually read and sometimes memorize the poems of these poets. Some of these poems have become common expressions and proverbs among Iranians [38]. On the other hand, the official religion of the country is Shiite Islam and this religious culture has been flowing throughout the history of this territory for centuries [39].

He said, “I am the muskdeer on account of whose gland this hunter shed my pure blood.

Oh, I am the fox of the field whose head they from the covert cut off for the sake of the fur.

Oh, I am the elephant whose blood was shed by the blow of the mahout for the sake of the bone.

He who hath slain me for that which is other than I, does not he know my blood sleepeth not?

Today it lies on me and tomorrow it lies on him: when does the blood of one such as I am go to waste like this?

Although the wall casts a long shadow, the shadow turns back again toward it.

This world is the mountain, and our action the shout: the echo of the shouts comes to us.”

The sword is in your hand but do not slay for God will recompense you on that day; the blade was no more forged for the unjust than grapes for outlawed wine are pressed to must.

The Prophet Jesus, strolling on a day, found at his feet a man slain on the way; and in amazement, spoke thus to the corpse;

“Whom did you murder, that now with such remorse, yourself lie slaughtered in the dusty lane?

By whom in turn shall he who killed, be slain?”

Don’t spoil your knuckles knocking at the gate of strangers; and be spared the blows of Fate.

Furthermore, many common Persian proverbs such as “whatever you put in the pot, come in your spoon,” “you reap what you sow,” “whatever you give with your hand, you get back from the same hand,” and “whatever you do, you do it to yourself, whether good or bad” are also proof of the existence of this cultural element. There are many references to this concept in Islamic teachings as well. For example, in the Holy Qur’an, verse 39 of Surah An-Najm: “and that a man shall not deserve but (the reward of) his own effort.” Also, verse 7 of Surah Al-Isra: “If you do good, you do good for yourselves; and if you do evil, [you do it] to yourselves. Then when the final promise came, [We sent your enemies] to sadden your faces and to enter the temple in Jerusalem, as they entered it the first time, and to destroy what they had taken over with [total] destruction.” Verses 7 and 8 of Surah Az-Zalzalah also indicate: “So whosoever does an atom’s weight of good shall see it. And whosoever does an atom’s weight of evil shall see it.” In verse 84 of Surah Al-Qasas, we read: “Whoever comes [on the Day of Judgment] with a good deed will have better than it; and whoever comes with an evil deed—then those who did evil deeds will not be recompensed except [as much as] what they used to do.”

The way people view the world is partly based on their socialization in the culture in which they were raised [40, 41]. Through a cultural lens, it was observed that “belief in the return of the results of actions to oneself” as a factor in preventing the commission of administrative corruption-related offenses might have been potentially affected by the cultural heritage of the participants. Of course, it should not be overlooked that the existence of potential cultural components in a society is not enough by itself, and how cultural teachings are transferred to people and how people internalize and actualize them is very important and can make a difference.

The research findings also showed that detachment-promoting thoughts and beliefs are associated with preventing administrative corruption. Thinking about death, refraining from comparing one’s level of welfare with others, and belief in the universality of financial problems are among these beliefs. Research shows that death awareness may move people toward doing right actions and may reduce their tendency toward unethical actions [42]. Remembering death probably causes people not to be so fond of the world, not to be seduced by its ornaments, and not to complain about its hardship and suffering perhaps because all these will disappear one day.

Explaining the role of “refraining from comparing one’s level of welfare with others” and “believing that financial problems are universal” in the prevention of administrative corruption, we support the idea that, as Peng [43] demonstrated, the level of perception of poverty is intensified as a result of comparing one’s life with various aspects of a prosperous life, and even when employees are paid well, since the feeling of need is rather subjective, they may compare themselves with employees of another organization who have more salaries than them. Due to such a comparison and the inability to respond to the infinite human needs, they may think that they have little income and this may be their justification for doing actions outside of moral and legal standards. Therefore, it seems that not comparing oneself with others and believing in the universality of financial problems can lead to a reduction in the perception of poverty among employees and may potentially help them avoid corrupt actions.

It should be noted that when discussing the function of detachment-oriented thoughts, we must differentiate it from that of workers′ preferences for job amenities. Employees do not work just to earn money, but they may also have other preferences in terms of job characteristics. In their study among the employees of cooperative credit banks in Italy, Nese and Troisi [44] focused on staff’s preferences for nonpecuniary characteristics to estimate their monetary valuations of nonmonetary job attributes such as low travel time, good work environment, probability of advancement, clear management rules, personal prestige, opportunities for learning/training, participation in decision-making processes, autonomy and responsibilities, and social aims. They found that low travel time is the most important attribute, followed by opportunities to learn. Moreover, the employees would be willing to accept a lower income in exchange for job characteristics such as low travel times, prospects for advancement, good working environment, potential for learning, and achievement of social aims (e.g., local development). Rowden [45] also underlined the positive association between workplace learning (both formal and informal) and job satisfaction in the context of small- to mid-sized firms. Lyons et al. [46] proposed that workers in the nonprofit sector value the societal contribution of their profession and the sense of personal fulfillment that they gain from their work. Put differently, employees in nonprofit firms are responsive not only to monetary incentives but also to the perceived social value of their job [47]. However, Bright’s [48] study on public service motivation indicated that in the public sector, in spite of its social impact, civil servants do not perceive their occupation as socially valuable as the nonprofit sector staff.

The findings also showed that, from the perspective of the participants, self-oriented conservative personality traits are tied to prevention of corruption. Contentment and lack of ambition, conscientiousness, risk aversion, hope for the future, and self-control were among these characteristics. Greed and ambition have been shown to be one of the factors of administrative corruption [5, 19, 20, 22–24]; therefore, here contentment is considered a protective factor. Work ethic and conscientiousness have been identified in the studies conducted by Rostami et al. [25] and Farhadinejad [20] in the field of corruption. Conscientiousness indicates being accurate and careful. Conscientious people tend to do every job well and take their duties toward others seriously [49]. Therefore, it seems that the participants with this personality characteristic took their duties and responsibilities more seriously and engaged in their work without violating ethics and law. Based on the previous studies [20, 24], high risk tolerance is one of the personality factors of committing corruption. It seems that the risk aversion factor identified in this study may have caused the participants to avoid deterrent punishments or other undesirable cases and not to take risks to commit cases of administrative corruption. High levels of risk aversion can cause a person to consider the risk higher than the potential reward when deciding to commit corruption. Therefore, this issue can play a role in the cost-benefit analysis proposed in rational choice theory.

“a moral dilemma emerges when different motivations of human behavior dictate opposite actions in a given decision-making context. In economic situations, the most appealing type of dilemma concerns the conflict between selfish monetary reward maximization and adherence to some ethical prosocial norm, especially when the latter implies an economic loss. The emotional implications of such conflicts seem to originate from the interplay between a basic impulse for greedy money-seeking motivations and alternative, more sophisticated social and personal ethical norms.”

In addition, the results of this study showed that the participants used some self-care strategies: leaving the job situation that induces corruption, continuous self-monitoring, and giving oneself an opportunity for reflection and not making premature decisions. An important contextual factor in administrative corruption is the corrupt atmosphere of the organization [27]. Therefore, leaving the situation contaminated with corruption can be a preventive strategy, which was also mentioned by some of our participants. The function of continuous self-monitoring in preventing administrative corruption can be explained through the slippery slope theory [13]. In the “slippery slope” hypothesis of corrupt behavior, small acts of corruption and crimes gradually lead to bigger ones. Therefore, the informants of the current study, using the continuous self-monitoring strategy, probably took special care of themselves so as not to enter this slippery slope. In addition, “giving oneself an opportunity for reflection and not making premature decisions” is another strategy that may help a person less likely to fall into the trap of heuristics. According to Rangone [17], rationality has a limited capacity to evaluate risks and possibilities and it may be guided by biases and heuristics. Therefore, it seems that deliberate and unhurried decision making can be considered as a way to avoid corruption.

5. Conclusions

Persistent corruption has been a long-standing challenge in Iran. Although the topic of corruption prevention has attracted a great deal of attention, existing research concerning micro-level factors is sparse. Our study among a group of public employees in Iran identified some of the potential individual and contextual factors contributing to administrative corruption prevention from the perspective of participants. Attempts were made to explain the results through relevant theories, logical arguments, and cultural components. In general, according to the findings of this research, it seems that if there is a financial need and also an opportunity to commit corruption, what can potentially help a person in self-control and self-restraint may be a set of psychological components (including cognitions, emotions, behavioral strategies, and personality traits) and some contextual factors (e.g., family context and organizational context).

This study is just a small attempt to identify and clarify the possible role of individual and contextual factors in the prevention of administrative corruption. The main strength of this research is that, to the researchers′ knowledge, this is the first comprehensive scientific study of its kind in Iran, which examines the perception of civil servants about individual and contextual factors that contribute to prevention of administrative corruption; also, a qualitative method was especially used to gain more insight into this phenomenon. This study, by discovering some of the factors associated with a group of public employees refraining from committing possible administrative corruption, may contribute to the enrichment of knowledge in the field of occupational fraud. Previous research concerning administrative corruption has often focused on the macro-aspect, and the micro-aspect (etiology focused on the individual perspective) is understudied. In the few existing studies, the participation of “perpetrators of corruption” has been used, and therefore, the approach of the present study in recruiting “nonperpetrators of corruption” as a research sample and adopting a positive and preventive point of view is innovative. Thus, since most studies focus on the factors that lead to corruption, the idea of examining the contextual and individual factors tied to corruption prevention and resistance to corruption is new. It is hoped that this study will help increase the depth and scope of the literature on phenomenology of corruption, administrative corruption management, and public sector ethics.

It should be noted that we never intend to reduce the phenomenon of (non-) involvement in corruption to personal-level processes, but such micro-level findings may, hopefully, serve as potential pieces of the multifaceted puzzle of corruption prevention. As a crucial point regarding macro-level determinants, it should not be overlooked that Iran currently faces a high level of economic inflation. Inflation can undermine not only the economic foundations but also the moral fabric of society. Just as one cannot expect greens and flowers to grow in dry and salty lands, individual improvement requires a conducive environment.

5.1. The Limitations of the Study

The main limitation of this research is the use of convenience sampling. Furthermore, considering the sampling through the announcement of a call, the findings of this study do not reflect the experience of those who did not see the call or did not want to volunteer. Due to the sensitivity of the subject under investigation, probably some of those who could potentially be part of the volunteers did not express their interest. Participants who chose to be part of the study may have different characteristics than those who did not, potentially skewing the results (self-selection bias). Another limitation of this study is the sampling bias, as our sample was predominantly male. Therefore, we should be aware of the effect of gender, but we can hardly explain this effect on the results. In addition, the participants were not all from a specific organization, and therefore, the sample was not homogeneous in terms of the nature of the job and workplace. Given the role of subjectivity in qualitative research, the data collection and analysis processes may have been influenced by the researchers′ perspectives and biases. It is clear that due to the qualitative nature of this research as well as the limitations mentioned, our findings cannot be generalized and several complementary studies are needed to support these results.

5.2. Directions for Future Research

- •

In this study, as the first comprehensive study in the field in Iran, a general approach was adopted toward civil servants and types of administrative corruption. Considering that the environment of different organizations as well as the nature of the people who are usually employed in them may be different, it is recommended to recruit the sample from a specific public sector organization. Studies can be more detailed and deeper depending on the available types of corruption, white-collar crime, and workplace deviance.

- •

The development and validation of a questionnaire to measure individual-oriented strategies to deal with the temptations of corruption can be an interesting subject for future studies; thus, the basis for conducting quantitative and mixed-method studies is provided.

- •

Researching corruption and self-interested behavior from a psychological perspective is relatively new. Further inquiries into the psychopathology of corruption and the psychology behind corruption deterrents will likely provide counter-corruption departments and anti-corruption practitioners with more scientific evidence to rely on.

5.3. Practical Implications and Policy Recommendations

- •

It is suggested to pay more attention to individual factors and contextual factors in the programs to prevent and control corruption. These factors can be taken into consideration when designing measures and policies aimed at promoting ethical governance and reducing corrupt behaviors in public agents. Prevention policies must be seen in a multidisciplinary way, and focusing on micro-level factors can enhance the effectiveness of public sector strategies in curbing corruption.

- •

In line with combating corruption and administrative violations, various institutions seek to implement anti-corruption laws, but even if the toughest laws are passed and implemented, as long as people in any position do not believe in personal ethics, business ethics, and moral values, they may think of circumventing the laws. It is necessary to see which factors underlie the internal control of the public servants employed by government departments or agencies for public sector undertakings. Additionally, regular training and a transparent system for reporting and addressing corruption can empower employees to act with integrity.

- •

The findings of this study can be incorporated into developmental crime prevention strategies. Families and schools should be provided with resources to address the conditions that give rise to crime and corruption before these problems arise or become entrenched. We need a holistic view toward cultivating moral reasoning and moral resilience and reducing the frequency of public corruption cases in the long term. The best time to fight corruption is before it occurs.

- •

Understanding the factors that help prevent corruption among public employees is indeed crucial for improving governance and public trust. We recommend that planners and policymakers allocate more funds and facilities to facilitate the implementation of research projects with a focus on administrative processes and exercise of power in organizations, including its darker aspects like the abuse of power and corruption.

- •

Transparency Think Tank for Iran, General Inspection Office, Supreme Audit Court of Iran, Ministry of Justice, Judicial System of Iran, Special Prosecutor’s Office for Money and Banking Crimes, Law Enforcement Command (police force of the Islamic Republic of Iran), Iranian National Tax Administration, and municipalities can benefit from the results of this research. Moreover, “Fight against corruption” campaigns, governing officials, administrative policymaking groups, senior managers of government institutions and private companies, in particular, human resources and recruitment managers, experts of in-service training units and administrative violation boards, and specialists in the fields of management, professional ethics, criminology, behavioral ethics, organizational behavior, administrative sciences, behavioral public administration, psychology of corruption, auditing, law, forensic psychology, legal psychology, career counseling, and industrial-organizational psychology can use our findings at theoretical and practical levels.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Disclosure

This work is the result of a doctoral dissertation completed by Saeid Zandi in fulfillment of Ph.D. requirements at Allameh Tabataba’i University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Saeid Zandi and Masoumeh Esmaeili; data curation, Saeid Zandi; formal analysis, Saeid Zandi, Masoumeh Esmaeili, and Kumars Farahbakhsh; investigation, Saeid Zandi and Kumars Farahbakhsh; methodology, Saeid Zandi, Masoumeh Esmaeili, and Kumars Farahbakhsh; project administration, Saeid Zandi; resources, Saeid Zandi and Kumars Farahbakhsh; supervision, Masoumeh Esmaeili; writing–original draft, Saeid Zandi; and writing–review and editing, Saeid Zandi, Masoumeh Esmaeili, and Kumars Farahbakhsh.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of our informants who were cooperative in facilitating the interviews.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.