The Mediating Role of Perceived Body Weight, Fat, and Muscularity in the Relationship Between Weight Status and Psychological Health

Abstract

Background: Past studies have primarily focused on the impact of body weight perception on psychological health. However, other components (e.g., perceived body fat and muscularity) may also play a role. This study aimed to examine the association between weight status (i.e., normal weight and obesity/overweight) and psychological health, and how different components of body perception mediate the association.

Methods: From February to June 2022, 621 undergraduates completed an online cross sectional survey, which included questions about height, weight, psychological health (i.e., well-being, quality of life, depression, anxiety, and stress), and body perception. Participants with a body mass index (BMI) between 18.5 kg/m2 and 25 kg/m2 were classified as normal weight, while those over 25 kg/m2 were classified as individuals with obesity/overweight. Path analysis tested the association between weight status and psychological health and the mediating role of perceived body weight, fat, and muscularity.

Results: Obesity/overweight was associated with lower well-being (β = 0.128, p = 0.002) and physical health-related quality of life (β = 0.089, p = 0.024), and higher depression (β = −0.133, p = 0.002) and stress (β = −0.104, p = 0.013). These associations were fully mediated by perceived body fat, with estimates ranging from −0.122 to 0.112. Perceived body weight and perceived muscularity did not significantly mediate these associations.

Conclusion: Perceived body fat was the only component of body perception that explained the association between weight status and psychological health. This finding suggests that research on psychological health in individuals with obesity or overweight needs to extend beyond mere perceived body weight and incorporate different components of body perception. Furthermore, interventions aimed at improving psychological health in individuals with obesity or overweight need to consider the potential effect of perceived body fat.

1. Introduction

Overweight and obesity rates are on a global upswing. As of 2016, over half of the world’s adult population consists of people with obesity or overweight, marking a threefold increase since 1975, according to the World Health Organization [1]. In Australia, the situation mirrored the global trend. The Australian Bureau of Statistics [2] reported that 65.8% of the adult population consisted of people with obesity or overweight in 2022. The World Health Organization [1] defines overweight as a body mass index (BMI) greater than or equal to 25 kg/m2 and obesity as a BMI greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2. High BMI is a major public health concern because it is a leading risk factor for a number of physical health problems, such as cardiovascular diseases (mainly heart disease and stroke) [3], type 2 diabetes [4], musculoskeletal disorders (especially osteoarthritis) [5], and various forms of cancer [6, 7]. High BMI also has an impact on psychological health [8–15].

Psychological health within positive sychology is conceptualized as both the absence of psychological illness and the presence of positive qualities (e.g., well-being and good quality of life in the physical, emotional, social, and spiritual domains) [16, 17]. Previous research has found that higher BMI is associated with lower physical health-related quality of life [10, 14] and higher emotional distress (i.e., stress, anxiety, and depression) [18]. Obesity is also associated with greater risk of anxiety [9]. In addition, the raised prevalence of depression amongst those with obesity is widely documented [13], and a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that obesity was associated with an elevated risk of future depression [11]. Therefore, it is important to investigate the processes that may explain the association between higher BMI and poor psychological health.

Weight-based stigma, defined as the devaluation and denigration of an individual due to their body weight, and weight bias internalization (or self-directed weight stigma) have been linked to higher BMI and poor psychological health [19]. These phenomena are more prevalent among people with obesity or overweight. Correlations have also been found between higher BMI, higher frequency of weight stigma experiences, and greater weight bias internalization across the entire weight spectrum [20, 21]. Romano, Heron, and Henson [22] proposed that theoretical models explaining these associations should account for the role of certain aspects of body image, such as body dissatisfaction. Body image has two main components: (1) the perceptual component—the picture we have in our minds of the characteristics (i.e., the size, shape, and form) of our bodies and (2) the attitudinal component—the thoughts and feelings we have concerning these characteristics and our constituent body parts [23], including body dissatisfaction. Gavin, Simon, and Ludman [24] support Romano, Heron, and Henson’s [22] perspective and suggest that body dissatisfaction likely affects (by mediating or moderating) the association between obesity and psychological health. For example, Brdaric, Jovanovic, and Gavrilov-Jerkovic [25] found that body dissatisfaction moderated the relationship between higher BMI and higher levels of emotional distress in women. A longitudinal study also found that the positive effect of childhood overweight on depression is mediated through higher body dissatisfaction [26].

In addition, body perception has a significant role in psychological health. For example, perception of body weight during adolescence significantly predicted symptoms of depression and anxiety in young adulthood [27]. Perception of body weight has also been found to mediate the association between obesity and depression [28]. In addition, a systematic review reported that body perception was consistently found to mediate the association between obesity and depression [13]. However, despite growing knowledge of the role of body perception, our understanding is confined by the methodological limitations of existing studies.

One methodological limitation in previous research concerning the role of body perception in psychological health is that the predominant focus has been upon body weight [28–31]. For example, Gaskin et al. [30] examined the association between depression and perceived weight status and demonstrated that women who perceived themselves as being about the right weight were less likely to have depression compared with women who perceived themselves as being underweight or overweight. However, components of body composition, such as perceived levels of body fat and muscularity, may also affect psychological health. For example, Griffiths, Murray, and Touyz [32] demonstrated that dissatisfaction with body fat and muscularity were both associated with disordered eating in men. Dissatisfaction with body fat has also been found to predict depressive symptoms among gay men [33]. Further, in a meta-analysis investigating the associations between body dissatisfaction and anxiety and depression, Barnes et al. [34] stated that dissatisfaction with different components of body composition may be equally important and so accordingly encouraged future research to include different components (e.g., weight, fat, and muscularity) in a single model to test their relationship with psychological health. To address this limitation, the current study aimed to examine the roles of perceived body weight, fat, and muscularity in a single model to test their relationship with psychological health.

To achieve this, it is important not to confound the perception of body weight and perception of body fat as found in some previous research, despite body weight and body fat being distinct. An example of this problem is apparent in the methodology employed by Paulitsch, Demenech, and Dumith [28] to investigate the mediating role of perception of body weight in the association between obesity and depression. Paulitsch, Demenech, and Dumith [28] used the question “How do you feel today regarding your weight?”. However, the response options concerned perception of body fat (i.e., “very fat”, “fat”, “a little bit fat”, etc.), instead of perception of body weight per se (i.e., “overweight”, “about the right weight”, “underweight”, as used by [35]). Perceived body weight and fat should nevertheless be considered separate constructs because body weight and body fat are distinct, and they have different impacts on health. To illustrate, body weight can be affected by body fat and other components of body composition, such as muscle mass [36]. Therefore, an increase in body fat may not necessarily lead to an increase in body weight if, at the same time, there is a decrease in other relevant components, such as muscle mass. Furthermore, body weight and mortality have a U-shaped association [36], whereas increased body fat generally has a negative impact on health [37]. Therefore, it is important to consider perceived body weight, fat, and muscularity as three distinct constructs and investigate the extent to which each of these are associated with psychological health [34].

Hence, the present study served to contribute to the literature by investigating the mediating roles of all three components (i.e., perceived body weight, fat, and muscularity) in the association between weight status (obesity/overweight and normal weight) and psychological health. Perceived body weight, fat, and muscularity refer to an individual’s perception of their body weight, body fat mass, and body muscle mass. They are distinct but also interrelated, due to the aforementioned effect of fat and muscle mass on body weight. Therefore, it is essential to consider these constructs collectively for a comprehensive understanding of the role of body perception in psychological health. To provide a holistic understanding of psychological health, this study aimed to test the association of weight status with both positive and negative aspects of psychological health (i.e., the presence of positive qualities of psychological health and the absence of psychological illness). More specifically, this study investigated the association of weight status with well-being, the physical and mental components of health-related quality of life, depression, anxiety, and stress. We predicted that individuals with a weight status of obesity/overweight would likely experience poor psychological health (decreased well-being, the physical and mental components of health-related quality of life; and elevated depression, anxiety, and stress). We also predicted that perceived body weight, fat, and muscularity would mediate the association between weight status and psychological health. Consistent with previous studies, we included gender and age as control variables [9, 18].

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Undergraduate students from an Australian university were recruited from February 21 to June 1, 2022 through an advertisement posted on the online participant pool (SONA), which included a link to the online survey created using Qualtrics. The online survey was pilot tested twice. Using a group of postgraduate students, the survey was tested and improved to ensure the questions and response options were gender-neutral and culturally inclusive. The survey was then tested and improved using a group of undergraduate students to ensure the survey questions were clear, concise, and easy to understand. The survey materials are available in the supporting information. Eligibility criteria included being 18 years or older, in full-time enrolment at the university, and proficient in English. There were no other exclusion criteria. The University Ethics Committee approved the study on 25 February 2022 (reference number: 52022992436323), and all participants provided written consent for their data to be used in research. In return for participation, they received course credit.

Of the 898 respondents to the online survey, five participants identified “other” as their gender (nonbinary: four and gender fluid: one and were excluded from further analyses because of the limited number of participants in this category. In addition, 191 participants were excluded due to missing height or weight data (16 males and 175 females). Eighty-one underweight participants (8 men and 73 women) were also excluded from further analyses because the current study aimed to investigate why individuals with obesity or overweight were more likely to report poor psychological health compared to those with normal weight. This resulted in a total of 621 participants (male: n = 147, 23.67%; female: n = 474, 76.33%; mean age = 21.46; SD = 6.849). The majority of them were born in Australia (Australia: 83.09%, New Zealand: 0.48%, other places: 16.43%). Table 1 shows the demographic information of the participants by weight status. The SONA pool at the time consisted of 1740 participants, yielding a response rate of 51.32% prior to exclusions. After exclusions, the response rate was 35.69%.

| Variables | Obesity/overweight (n = 192) | Normal weight (n = 429) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/frequency | SD/% | Mean/frequency | SD/% | |

| 1. Age | 23.849 | 9.183 | 20.394 | 5.159 |

| 2. Gender | — | — | — | — |

| Male | 58 | 30.21% | 89 | 20.75% |

| Female | 134 | 69.79% | 340 | 79.25% |

| 3. Place of birth | — | — | — | — |

| Australia | 159 | 82.81% | 357 | 83.22% |

| New Zealand | 0 | — | 3 | 0.70% |

| Other | 33 | 17.19% | 69 | 16.08% |

| 4. Highest level of education | — | — | — | — |

| Never attended school | 0 | — | 1 | 0.23% |

| Primary school | 1 | 0.52% | 0 | — |

| Some high school | 7 | 3.65% | 8 | 1.86% |

| High school graduate | 151 | 78.65% | 385 | 89.74% |

| College/university graduate | 15 | 7.81% | 26 | 6.06% |

| Postgraduate masters | 3 | 1.56% | 2 | 0.47% |

| Postgraduate Ph.D. or doctorate degree | 0 | — | 0 | — |

| Other | 12 | 6.25% | 6 | 1.40% |

| Missing | 3 | 1.56% | 1 | 0.23% |

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

Depression, anxiety, and stress were assessed by the 21-item version of depression anxiety stress scale [38]. Its reliability and validity have been demonstrated among clinical and nonclinical samples [39, 40], and good reliability was demonstrated in the current study (α = 0.953). The scale consists of three seven-item subscales with a four-point Likert response scale, ranging from 0 to 3 (0 = did not apply to me at all; 1 = applied to me to some degree, or some of the time; 2 = applied to me to a considerable degree, or a good part of time; and 3 = applied to me very much, or most of the time). The total score for each subscale ranges from 0 to 21 with higher scores representing greater severity/frequency of experiencing each state over the past week.

2.2.2. Well-Being

Well-being was assessed by the WHO-5 well-being index [41] that comprises of five items with a six-point Likert response scale, ranging from 0 to 5 (0 = at no time; 1 = some of the time; 2 = less than half the time; 3 = more than half the time; 4 = most of the time; 5 = all of the time). The total score ranges from 0 to 25 with higher scores indicating greater well-being. The WHO-5 well-being index has adequate reliability and validity and has been extensively used across a wide range of study fields [42]. Reliability of the WHO-5 index is good in the current study (α = 0.883).

2.2.3. Health-Related Quality of Life

Health-related quality of life was assessed using the short form 12 health survey [43] that comprises of 12 items, with six items assessing each of the two components (i.e., physical health-related quality of life and mental health-related quality of life). The 12 items use various response scales (yes/no, three-point scale, five-point scale, and six-point scale), and the possible range of score for each item is converted to a number from 0 to 100. The average score for each component was used in the current study, with higher scores indicating greater physical and mental health-related quality of life, respectively. Ware, Kosinski and Keller [43] found support for the reliability and validity of the short form 12 health survey, which also demonstrated good reliability in the current study (α = 0.759).

2.2.4. Weight Status

BMI was calculated as weight (in kilograms/height2 (in meters)) for each participant after converting the self-reported body weight and height to the metric scale where necessary. Following the classification of BMI by the World Health Organization, BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 was categorized as underweight, BMI ≥ 18.5 kg/m2 and <25 kg/m2 was categorized as normal weight, and BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 was categorized as obesity/overweight [44]. Normal weight and obesity/overweight were coded as “1” and “0” for weight status, respectively.

2.2.5. Perceived Body Weight, Fat, and Muscularity

Perceived body weight, fat, and muscularity were evaluated based on the answers to the question “Do you consider yourself to be…?” This question has three different sets of response options. For body weight, the response options are “about the right weight”, “overweight”, and “underweight”. The same question and response options for measuring perceived body weight have been used in many studies [30, 45]. We modified these response options for measuring perceived body fat and muscularity. For body fat, the response options are “about the right size”, “too thin”, and “too fat”. For muscularity, the response options are “about the right size”, “not muscular enough”, and “too muscular”. The answers were coded as “1” and “0” = “just about right” and “not right” (e.g., “1” = “about the right weight” and “0” = “underweight” or “overweight” for perceived body weight).

2.2.6. Demographic Information

Demographic information, including age, gender, place of birth, and highest level of education completed, was collected by a self-report questionnaire, and is presented in Table 1.

2.3. Analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed using SPSS to describe the characteristics of the participants. The Shapiro–Wilk test was performed using SPSS to assess normality of the score distribution of the variables of psychological health.

Path analysis was performed using Mplus Version 8 [46] to test the association between weight status and psychological health. Maximum likelihood estimation robust to non-normality was used because the score distribution of the variables of psychological health were not normally distributed. Two models (models 1 and 2) were estimated with weight status being specified as the predictor of the variables of psychological health: (1) the negative aspect of psychological health, including depression, anxiety, and stress; (2) the positive aspect of psychological health, including well-being, and the physical and mental components of health-related quality of life. Gender and age were included as control variables and were specified as the predictors of the variables of psychological health in both models 1 and 2.

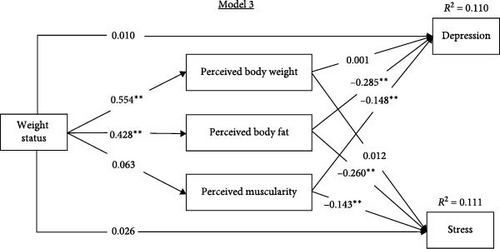

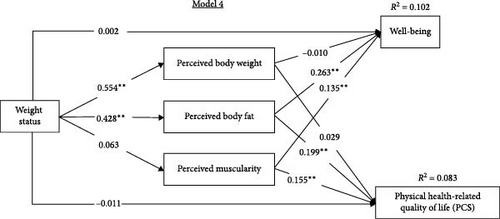

Path analysis was also performed to test the mediating roles of the body weight, fat, and muscularity perception. Maximum likelihood estimation with a bootstrap draw of 5000 samples was used. Two models (models 3 and 4) were estimated as depicted in Figures 1 and 2. Variables of psychological health were specified to be predicted by weight status via perceived body weight, fat, and muscularity. According to the results of model 1, gender, and age were included as the control variables, specified as the predictors of the negative aspect of psychological health in model 3. According to the results of model 2, gender was included as the control variable, specified as the predictor of the positive aspects of psychological health in model 4. Mediating effects were considered statistically significant when 95% bootstrap confidence intervals did not include zero [47]. According to Kline [48], an adequate sample size should be at least 10 times, and ideally 20 times, the number of parameters being estimated. The expected number of parameters being estimated was 36 and therefore a target sample size of at least 360, ideally 720, was set during the research design phase. In the current mediation models (models 3 and 4), the estimated parameters were 26 and 24, respectively. This suggests a required sample size of at least 260, ideally 520. Given the current sample size of 621, the sample size is adequate.

3. Results

Of the 621 participants, 69.08% had a BMI within the range of normal weight and 30.92% had a BMI within the obesity/overweight range. Characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 2. The results of the Shapiro–Wilk test suggested that distributions of the psychological health variables were not normally distributed (p < 0.001 for all variables of psychological health).

| Variables | Obesity/overweight (n = 192) | Normal weight (n = 429) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/frequency | SD/% | Mean/frequency | SD/% | |

| 1. Perceived body weight | — | — | — | — |

| Just about right | 53 | 27.60% | 361 | 84.15% |

| Overweight | 139 | 72.40% | 41 | 9.56% |

| Underweight | 0 | 0% | 27 | 6.29% |

| 2. Perceived body fat | — | — | — | — |

| Just about right | 36 | 18.75% | 279 | 65.03% |

| Too fat | 156 | 81.25% | 114 | 26.57% |

| Too thin | 0 | 0% | 36 | 8.39% |

| 3. Perceived muscularity | — | — | — | — |

| Just about right | 76 | 39.58% | 199 | 46.39% |

| Too muscular | 104 | 54.17% | 219 | 51.05% |

| Not muscular enough | 12 | 6.25% | 11 | 2.56% |

| 4. Depression | 7.068 | 5.839 | 5.921 | 5.157 |

| 5. Anxiety | 5.521 | 4.818 | 5.329 | 4.545 |

| 6. Stress | 7.849 | 5.168 | 7.110 | 4.865 |

| 7. Well-being | 12.344 | 5.165 | 13.497 | 5.105 |

| 8. PCS | 73.199 | 21.334 | 76.991 | 20.125 |

| 9. MCS | 50.464 | 20.515 | 52.251 | 19.874 |

| 10. BMI | 29.522 | 5.357 | 21.694 | 1.731 |

- Note: Normal weight: BMI ≥ 18.5 kg/m2 and <25 kg/m2; Obesity/overweight: BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2. MCS, mental health-related quality of life; PCS, physical health-related quality of life.

Table 3 presents the standardized path coefficients, p values, and R-square statistics for the associations between weight status and psychological health. In model 1, the weight status of obesity/overweight was significantly associated with higher levels of depression and stress, but the association between weight status and anxiety was not significant. As the control variables, gender, and age were significant predictors of depression and anxiety. While gender was a significant predictor of stress, age was not. In model 2, the weight status of obesity/overweight was significantly associated with lower levels of well-being and physical health-related quality of life, but the association between weight status and mental health-related quality of life was not significant. As the control variables, gender was a significant predictor of well-being, physical and mental health-related quality of life, but age was not.

| Model pathways | β | p | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| Weight status → depression | −0.133 | 0.002 | — |

| Age → depression | −0.110 | 0.010 | 0.029 |

| Gender → depression | 0.086 | 0.024 | — |

| Weight status → anxiety | −0.076 | 0.059 | — |

| Age → anxiety | −0.173 | <0.001 | 0.056 |

| Gender → anxiety | 0.163 | <0.001 | — |

| Weight status → stress | −0.104 | 0.013 | — |

| Age → stress | −0.076 | 0.052 | 0.038 |

| Gender → stress | 0.165 | <0.001 | — |

| Model 2 | |||

| Weight status → well-being | 0.128 | 0.002 | — |

| Age → well-being | 0.053 | 0.221 | 0.027 |

| Gender → well-being | −0.117 | 0.003 | — |

| Weight status → PCS | 0.089 | 0.025 | — |

| Age → PCS | −0.038 | 0.402 | 0.024 |

| Gender → PCS | −0.125 | 0.001 | — |

| Weight status → MCS | 0.064 | 0.120 | — |

| Age → MCS | 0.032 | 0.446 | 0.024 |

| Gender → MCS | −0.146 | <0.001 | — |

- Note: MCS, mental health-related quality of life; PCS, physical health-related quality of life.

Figures 1 and 2 present the standardized path coefficients and R-square statistics for the models testing the mediating role of body weight, fat, and muscularity perception. In both models 3 and 4, the direct paths between the variables of weight status and psychological health were no longer significant when the mediating role of body weight, fat, and muscularity perception was estimated. As the control variables, gender (β = 0.099, p = 0.010) and age (β = −0.048, p = 0.030) remained significant predictors of depression. Gender was also a significant predictor of stress (β = 0.177, p < 0.001), well-being (β = −0.128, p = 0.001), and physical health-related quality of life (β = −0.137, p < 0.001). In both models 3 and 4, normal weight was significantly and positively associated with the perception that one is about the right weight; normal weight was also significantly and positively associated with the perception that one has about the right amount of body fat. However, the association between weight status and perceived muscularity was not significant in either model. In model 3, the perception that one has about the right amount of body fat was significantly associated with lower levels of depression and anxiety; the perception that one has about the right amount of muscle was also significantly associated with lower levels of depression and anxiety. However, perceived body weight was not significantly associated with depression or anxiety. In model 4, the perception that one has about the right amount of body fat was significantly associated with higher levels of well-being and physical health-related quality of life; the perception that one has about the right level of muscle was also significantly associated with higher levels of well-being and physical health-related quality of life. However, perceived body weight was not significantly associated with well-being and physical health-related quality of life.

Table 4 presents the standardized estimates for direct, indirect, and total effects, and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In both models, the direct effects between the variables of weight status and psychological health (i.e., depression, stress, well-being, and physical health-related quality of life) were not significant. Of the specific indirect pathways from weight status to depression, stress, well-being, and physical health-related quality of life, only the pathways through perceived body fat were significant.

| Model pathways | Direct | Indirect | Total effects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | (95% CI) | Estimate | (95% CI) | Estimate | (95% CI) | ||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||

| Model 3 | |||||||||

| BMI → depression | 0.010 | −0.079 | 0.100 | — | — | — | −0.121 ∗∗ | −0.203 | −0.037 |

| BMI → weight → depression | — | — | — | 0.001 | −0.056 | 0.057 | |||

| BMI → fat → depression | — | — | — | −0.122 ∗∗ | −0.167 | −0.081 | |||

| BMI → muscle → depression | — | — | — | −0.009 | −0.024 | 0.002 | |||

| BMI → stress | 0.026 | −0.062 | 0.115 | — | — | — | −0.087 ∗∗ | −0.169 | −0.063 |

| BMI → weight → stress | — | — | — | 0.007 | −0.048 | 0.062 | |||

| BMI → fat → stress | — | — | — | −0.111 ∗∗ | −0.157 | −0.068 | |||

| BMI → muscle → stress | — | — | — | −0.009 | −0.023 | 0.002 | |||

| Model 4 | |||||||||

| BMI → well-being | 0.002 | −0.091 | 0.094 | — | — | — | 0.117 ∗∗ | 0.040 | 0.194 |

| BMI → weight → well-being | — | — | — | −0.006 | −0.061 | 0.050 | |||

| BMI → fat → well-being | — | — | — | 0.112 ∗∗ | 0.073 | 0.155 | |||

| BMI → muscle → well-being | — | — | — | 0.009 | −0.002 | 0.023 | |||

| BMI → PCS | −0.011 | −0.100 | 0.076 | — | — | — | 0.100 ∗ | 0.020 | 0.179 |

| BMI → weight → PCS | — | — | — | 0.016 | −0.040 | 0.070 | |||

| BMI → fat → PCS | — | — | — | 0.085 ∗∗ | 0.045 | 0.129 | |||

| BMI → muscle → PCS | — | — | — | 0.010 | −0.001 | 0.024 | |||

- Note: BMI, Weight status; CI, non-symmetric confidence interval; Fat, perceived body fat; Muscularity: perceived muscularity; PCS, physical health-related quality of life; weight, perceived body weight.

- ∗95% confidence interval does not overlap with zero and ∗∗99% confidence interval does not overlap with zero.

4. Discussion

The current study aimed to examine the association between weight status and psychological health, as well as to explore the mediating roles of perceived body weight, fat, and muscularity in this association. Results showed that: (1) compared with individuals with a normal weight, people with obesity or overweight presented significantly higher levels of depression and stress, and significantly lower levels of well-being and physical health-related quality of life; (2) weight status was a significant predictor of perceived body weight and fat, but not perceived muscularity; (3) perceived body fat and muscularity, but not perceived body weight, significantly predicted the negative and positive aspects of psychological health; (4) perceived body fat fully mediated the association of weight status with depression, stress, well-being, and physical health-related quality of life. Taken together, the results demonstrate that the weight status of obesity/overweight/is associated with lower levels of psychological wellness and higher levels of psychological problems. Additionally, this association appears to be the product of the association of weight status with perceived body fat and the association of perceived body fat with psychological health. These findings provide a fruitful extension of research on how individuals with obesity or overweight may experience poor psychological health [9, 11, 13], and therefore provide insight for guiding clinical practices, public health measures, and strategies.

Evidence has previously been established for the longitudinal association between obesity and subsequent psychological illnesses, such as depression [49, 50]. However, the association between weight status and the positive aspects of psychological health, such as well-being, has received less research attention. The current study serves as an extension of the literature by providing evidence that the weight status of obesity/overweight is related to the negative aspects of psychological health (i.e., higher levels of stress and depression) and inversely related to the positive aspects of psychological health (i.e., lower levels of well-being and physical health-related quality of life). Regarding nonsignificant associations, the relationship between weight status and mental health-related quality of life was not significant in the current study. This finding is consistent with previous findings of a meta-analysis [14]. However, the current study did not find a significant relationship between weight status and anxiety. This finding is inconsistent with a previous study using a German sample that found people with obesity or overweight reported significantly higher levels of anxiety, compared with individuals with a normal weight [9]. Nonetheless, other studies [51, 52] have also found no significant association between weight status and anxiety. A possible explanation for these inconsistent findings is that the participants in different studies investigating the association are heterogeneous in terms of their demographic data, such as ethnicity. An epidemiologic study found ethnic differences in the association between BMI and anxiety, demonstrating that anxiety was significantly associated with obesity in the black population, but not in the Asian or Hispanic populations [53]. In addition, DeJesus et al. [53] found a U-shaped association between BMI and anxiety in the white population. Although data on ethnicity was not collected in the current study, the characteristics of participants in the current SONA participant pool showed that about 42.4% of the SONA participants were Caucasian, 25% were Asian, 11.2% were Middle Eastern, 1% were Indigenous Australian, and the rest of the SONA participants were from other backgrounds or did not provide the information. Therefore, it is unlikely that all participants of the current study have the same ethnic background, which may have affected our ability to detect a significant association between weight status and anxiety.

The current study is the first to test the role of perceived body weight, fat, and muscularity in a single model. The associations of perceived body fat and muscularity with the psychological health variables (i.e., well-being, physical health-related quality of life, stress, and depression) tested were significant. However, the current study did not find a significant association of perceived body weight with any of the psychological health variables tested, although a previous study demonstrated a significant association between perceived body weight and depression [30]. One explanation may be that perceived body weight was the only variable of body perception tested in the study of Gaskin et al. [30], while the current study tested the role of perceived body weight, fat, and muscularity in a single model. Since both women and men increasingly prefer a body with low body fat and toned muscles over weighing less [54], compared with perceived body fat and muscularity, perceived body weight may be a weaker predictor of psychological health, and hence the current study did not find a significant association of perceived body weight with psychological health when the role of perceived body weight, fat, and muscularity were tested within a single model.

Regarding the associations between weight status and perceived body weight and fat, people with obesity or overweight were less likely to consider themselves to be about the right weight and to have about the right amount of body fat. Regarding muscularity, a previous study found that higher perceived muscularity is associated with higher BMI among men [55], but whether this finding extends to women is unknown. In the current study, weight status was not significantly related to perceived muscularity. This could be due to the majority of the participants of the current study being female (76.3%), leading to not enough male participants for detecting a significant association between weight status and perceived muscularity. Although this distribution is relatively close to the gender imbalances in Australian higher education (i.e., female: 59%, male: 41% in 2019), it does not reflect the gender distribution in the general population [56]. Therefore, future studies could further examine the associations between perceived body weight, fat, and muscularity and weight status in males and females separately.

The current study extends upon existing literature by investigating the mediating roles of perceived body weight, fat, and muscularity in a single model for examining the mechanism underlying the relationship between the weight status of obesity/overweight and psychological health. Amongst these factors, perceived body fat was the sole variable that significantly mediated the associations between weight status and psychological health. Nevertheless, the association between weight status and psychological health was fully explained by the association between weight status and perceived body fat as well as the association between perceived body fat and the psychological health variables tested (i.e., well-being, physical health-related quality of life, stress, and depression). In contrast, only about 40% of the association between obesity and depression was mediated by body weight perception when Paulitsch, Demenech, and Dumith [28] tested the mediating role of body weight perception. Therefore, the findings of the current study advance our understanding of the associations between weight status and psychological health by demonstrating the critical role of perceived body fat.

The findings of the current study also provide valuable insights to further develop existing weight stigma models that do not explicitly account for the role of body image in the associations between weight status and psychological health. For example, Tomiyama [57] introduced the cyclic obesity/weight-based stigma model to elucidate the mediational role of weight-based stigma in the associations between elevated weight and emotional distress (e.g., stress, anxiety, and depression). However, previous research has consistently found correlations between weight-based stigma, weight bias internalization, and aspects of body image, such as body dissatisfaction [22, 58]. In addition, Romano, Heron, and Henson [22] found evidence for a sequential mediational mechanism, where weight-based stigma led to weight bias internalization, body dissatisfaction, and more eating disorder symptoms. Therefore, it is plausible that including perceived body weight, fat, and muscularity in existing weight stigma models may improve our understanding of the underlying mechanisms that explain the associations between weight status and psychological health. Future research could examine models that account for the role of weight-based stigma, weight bias internalization, and perceived body weight, fat, and muscularity to further investigate the associations between weight status and psychological health.

Despite being a valuable addition to the existing literature, the cross-sectional nature of this study does not allow us to infer causality. Additionally, this study relied on self-reported data, which could introduce bias, such as social desirability or recall bias. Therefore, the current findings should be viewed as preliminary evidence. Future studies using longitudinal data, experiment designs, or multiple data sources (e.g., interviews) are required to validate the mechanism. Another limitation was the use of self-reported weight and height instead of weight and height information that is measured by trained health technicians. This might have affected the current findings if participants under- or over-estimated their weight and height. However, self-reported weight and height for the calculation of BMI have been shown to have acceptable levels of accuracy in a similar participant sample [59], and are widely used in many health survey studies [18, 28, 60].

Further, this study used a student sample but did not measure the potential effect of factors such as academic stress, which are uniquely relevant to students. Hence, the present results ought to be considered as initial evidence. In addition, compared to studies that used nationally representative samples [30], the use of online participant pool and online survey likely introduced sampling biases. Participants in the current study were likely in their late teens or early twenties and academically successful enough to be enrolled in a university. Therefore, our sample is not representative of the general adult population. It is recommended that future studies should use nationally representative samples to examine whether the current findings could be generalized.

Finally, the data on ethnicity were not collected, preventing the investigation of possible ethnic differences in the association between weight status and psychological health. The number of male participants of the current study (n = 147, 23.67%) also limited our ability to examine potential gender differences in the association between weight status and psychological health and the mediating role of body perception. Therefore, future studies could replicate this study in different ethnic groups, in larger and more gender-balanced samples to allow ethnicity-specific and gender-specific analyses. In addition, we modified the response options of a widely used survey question of perceived body weight to assess perceived body fat and muscularity in this study. The reliability and validity of the response options used for assessing perceived body fat and muscularity should be compared to other commonly used figural rating scale, such as Somatomorphic Matrix [61] and Stunkard Figure Rating Scale [62] to provide further support to our measures and findings.

5. Conclusions

The current study presented evidence for perceived body fat as a potential mechanism explaining how people with obesity or overweight report higher levels of stress and depression, and lower levels of well-being and physical health-related quality of life. These findings suggest that research on psychological health in individuals with obesity or overweight needs to extend beyond mere perceived body weight and consider the role of perceived body fat when designing intervention for treating psychological problems and promoting psychological wellness among individuals with obesity or overweight.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the University Ethics Committee.

Consent

Participants provided written consent for their data to be used in research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Catie Lai contributed to conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing the original draft, writing the review and editing, visualization, and project administration. Kevin R. Brooks contributed to writing the review and editing and supervision. Simon Boag contributed to writing the review and editing and supervision.

Funding

Catie Lai was awarded a scholarship funded by the Macquarie University Research Excellence Scheme. Open access publishing facilitated by Macquarie University, as part of the Wiley - Macquarie University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Acknowledgments

Catie Lai was awarded a scholarship funded by the Macquarie University Research Excellence Scheme. Open access publishing facilitated by Macquarie University, as part of the Wiley - Macquarie University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support this study cannot be publicly shared due to ethical or privacy reasons and may be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author if appropriate.