Patient Perceptions of Physical Rehabilitation and Its Method of Delivery for a Variety of Adverse Physical Effects following Breast Cancer Surgery: An Observational Mixed Methods Study

Abstract

Purpose. To investigate patient perceptions of physical rehabilitation received for various adverse physical effects following breast cancer surgery and the content and delivery methods of the physical rehabilitation received. Methods. Cross-sectional study of 509 Australian women living with breast cancer (n = 178 (35%) (Breast Conserving Surgery (BCS)), n = 168 (33%) (Mastectomy (MAST)), and n = 163 (32%) (Breast Reconstruction Surgery (BRS)). Retrospective, online survey investigated the physical rehabilitation received after surgery/treatment. The survey explored the respondents′ perceptions (open response) and satisfaction levels with the physical rehabilitation received and its content and delivery method (closed responses). Perceptions were analyzed using a thematic analysis; satisfaction levels and delivery methods for each adverse physical effect were tabulated. Results. Major perceptions: (i) unaware of and unprepared for adverse physical effects, (ii) unsuitable information delivery, and (iii) insufficient follow-up from health professionals. Physical rehabilitation content focused on shoulder issues and lymphedema; less than half of respondents received any information about scars, torso, and donor site issues or physical discomfort disturbing sleep. The proportion that received each delivery method varied for each adverse physical effect. Pamphlets and verbal instruction were the most common delivery methods and sessions with health professionals where issues were physically assessed, checked, or progressed the least common. Satisfaction levels varied for each adverse physical effect; all were less than 50%. Conclusion. Women perceived their physical rehabilitation did not prepare them for the adverse physical effects they experienced, the method and timing of delivery did not meet their needs at various stages of recovery, and the follow-up was insufficient. Quantitative data on the content and delivery method support these perceptions. Explanations of why these perceptions occurred and recommendations to improve physical rehabilitation through greater use of patient-related outcome measures and spreading limited physical rehabilitation resources using a three-level model of care are recommended. Although many women recover from breast cancer, improved physical rehabilitation could enable women to manage any immediate or long-term side effects of their breast cancer surgery and treatment.

1. Introduction

The increased number of women living with breast cancer has enabled greater emphasis to be directed towards physical recovery from breast cancer surgery/treatment to maximise long-term health and quality of life [1–8]. Physical recovery is required for the adverse physical effects of breast cancer surgery and treatment related to shoulder [3, 9–20] and torso issues [3], scars [3, 11, 14, 15, 17, 19, 21, 22], bra discomfort [3, 21, 23], physical discomfort disturbing sleep [3], donor site issues [3, 9], and lymphedema [3, 9, 11, 13, 14, 17, 19, 20, 24–27]. A high percentage of women perceive these adverse physical effects to be frequent and severe [3], and to last for years [5, 16, 17, 19, 28]. Moreover, poor physical recovery limits women from being physically active, resuming sport, paid work, and daily tasks [14, 16, 19, 20, 27–33], and so has health, economic, and quality of life consequences.

Many of these adverse physical effects, however, are responsive to physical rehabilitation [7, 11, 14, 24–26, 28, 34–43]; early intervention and treatment can minimise their duration, progression, and impact [3, 8, 11, 14, 24,26, 28, 38, 40, 42, 44–47]. Prehabilitation, prospective surveillance, and multidisciplinary models of care promote early detection and intervention [11, 14, 25, 26, 38,40, 42, 45, 48–52]. Within these models, assessment of physical function begins at diagnosis with education, which continues through and beyond treatment, and instigates comprehensive rehabilitation involving a multidisciplinary team [32]. In research studies, prehabilitation, prospective surveillance, and coordinated multidisciplinary rehabilitation have effectively prevented the onset, complexity, or progression of arm and torso morbidity and lymphedema [8, 51, 53, 54]. The essential components of survivorship care include prevention surveillance, intervention, and coordination of care [53], which together optimize the functional status of women living with breast cancer to enable them to resume sport, work, and life roles and maximise their quality of life and long-term health [20, 28, 32, 40, 42, 45, 48]. They are also cost-effective because they limit progression and sequelae, which are more complex and costly to manage.

Despite these benefits, translating prospective surveillance and comprehensive cancer rehabilitation services into clinical practice has many barriers and is consequently limited [11, 14, 32, 34, 39, 40, 42, 45, 55–58]. More commonly, a traditional, reactive, impairment-based rehabilitation model is used that relies on the oncologist or surgeon identifying physical impairments or swelling (i.e., with lymphedema) and then referring on a case-by-case basis for treatment by a physical therapist, occupational therapist, or exercise physiologist. Physical therapy is not a standard component of cancer care in many healthcare systems [40, 42, 45, 49]. In addition, because the referral process lacks standardized criteria and inconsistent communication, the referral is commonly delayed until the physical impairment or lymphedema is more advanced [42, 45, 46, 59].

Patient perceptions of their physical rehabilitation after breast cancer surgery, investigated in focus groups and semistructured interviews, show women are ill-informed of possible adverse physical effects, have limited access to coordinated comprehensive care, and receive inadequate attention from healthcare providers [32, 34–36, 53, 59, 60]. Physical therapists involved in cancer care also perceive that patient needs are not met by the physical rehabilitation provided in clinical practice [34, 35, 47, 56]. Most research on prospective surveillance has been in Canada, America, and Europe [48, 61]. Further research on the physical rehabilitation women receive in Australia could provide insight into the translation of prospective surveillance within Australia and facilitate the development of strategies to improve physical rehabilitation [32, 34–36, 61, 62].

The study aimed to investigate patient perceptions of physical rehabilitation received for various adverse physical effects following breast cancer surgery and the content and delivery methods of the physical rehabilitation they received. We hypothesized that respondents would perceive the physical rehabilitation they received did not meet their needs, that a low percentage of women would be satisfied with their physical rehabilitation, and that data on the content and delivery of physical rehabilitation education and treatment received would support these perceptions.

2. Participants and Methods

2.1. Participants

We invited women over 18 years who had breast cancer surgery within the previous 10 years to participate in an anonymous online survey advertised across Australia on breast cancer websites (Breast Cancer Network Australia, Register4, Reclaim Your Curves, and breast cancer support groups). The exclusion criteria were metastatic breast cancer. Tacit consent was deemed by respondents clicking an “agree” button after the participant information sheet on the survey. The methodology was approved by the University of Wollongong Human Research Ethics Committee (HE15/453).

2.2. Online Survey

Survey development was based on previous breast cancer education/exercise intervention studies [14, 37], research on the common adverse physical effects following breast cancer surgery [16, 21, 29], and semistructured interviews with oncology physiotherapists where we investigated the common adverse physical effects and education and treatment content and delivery methods (n = 6). The entire survey had three parts: (i) the adverse physical effects commonly experienced and their effect on physical activity/function; (ii) access to treatment following different types of breast cancer surgery (standard care versus independently accessed); and (iii) patient perceptions of physical rehabilitation, its method of delivery, and satisfaction ranking (see supplementary files). This paper will present the data on part three of the survey, patient perceptions of physical rehabilitation, and its content and delivery method. Parts one and two of the survey are published elsewhere [3, 63].

Quantitative data on the delivery method of physical rehabilitation education and treatment for seven common adverse physical effects were asked in 18 closed questions. The adverse physical effects were: pain, decreased range-of-motion and muscle strength associated with: (i) scars, (ii) shoulder, (iii) torso and (iv) donor site issues (only for respondents with autologous breast reconstruction); (v) lymphedema, (vi) physical discomfort disturbing sleep, and (vii) bra discomfort (i.e., difficulty finding a comfortable bra). Respondents were asked to select the delivery format that best described the highest level of education/treatment they received from four to six options for each adverse physical effect. The options were consistently ranked from lowest to highest level of care. For example, the options for scar issues were (i) No one gave me any information about massaging my scars; (ii) I was told to massage my scars, with no detailed instructions; (iii) I was told to massage my scars and given detailed instructions; (iv) Someone demonstrated how to massage my scars; (v) Someone massaged my scar for me; and (vi) Someone checked that I was massaging my scar correctly. Respondents were then asked to rank their satisfaction level with the physical rehabilitation received for each adverse physical effect as satisfied, neutral, or dissatisfied. Lastly, responents were asked their perceptions of the physical rehabilitation they received and recommendations to improve physical rehabilitation (open-ended questions).

The survey also collected data on age, residential location, cancer surgery/treatments, lymph node removal, postoperative complications, healthcare system where they had their surgery (public/private), and preexisting musculoskeletal issues. Representatives from Breast Cancer Network Australia, Register4, regional breast cancer support groups, three clinicians, and three women with breast cancer conducted face validity of the survey questions using the think-aloud technique. Minor changes to language were made following face validity testing. Reliability of the survey was established by having three patients complete the survey twice, 2 weeks apart, and comparing their responses. These responses were found to have high reliability. This survey section took approximately 10 minutes to complete and was open for 10 months (July 2017 to April 2018) on Qualtrics (v0217; Provo, UT). Of the 729 women who visited the link to the site, 625 completed the survey (85.7% completion rate).

2.3. Statistics

We tabulated the percentage of respondents that received each delivery format for each adverse physical effect and their satisfaction ranking. A thematic analysis was used to identify, analyze, and report the main themes of the patient perceptions. These were extracted and entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Iterative coding of the dataset and familiarization was achieved by reading and rereading the extracted data. The primary researcher (DM) generated initial coding and with a secondary researcher (AM), the themes were reviewed and defined. The final themes and exemplary quotes to authenticate the themes were determined through consensus of both researchers. SPSS Statistics v26.0 for Windows (IBM® Inc., Armonk, U.S.A.) was used for all descriptive statistics.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Six hundred and twenty-five respondents fully completed the survey, which equates to approximately 1% of the 79,720 people living with breast cancer in Australia (diagnosed from 2013 to 2017) [64]. Respondents who completed the survey within ten years of their surgery (mean 4.5 years, SD 2.9 years) were included in the quantitative analysis (n = 509; 81% of respondents). Fifty-five percent (n = 281) of respondents completed the open responses of the survey for the qualitative analysis. The flow of participants and participant characteristics are displayed in Figure 1 and Table 1. The mean age of respondents was 59.5 years (SD 9.3 years, with range 29–85 years). Of the 509 respondents, n = 178 (35%) had Breast Conserving Surgery (BCS), n = 168 (33%) had a Mastectomy (MAST), and n = 163 (32%) had Breast Reconstruction Surgery (BRS), of which 99 (51%) had implant-based reconstructions and 97 (49%) had autologous reconstructions.

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Type of surgery | |

| Breast conserving surgery (BCS) | 178 (35) |

| Mastectomy (MAST) | 168 (33) |

| #Breast reconstruction surgery (BRS) | 163 (32) |

| Age | |

| Breast conserving surgery (yrs: mean (SD)) | 60.8 (8.2) |

| Mastectomy (yrs: mean (SD)) | 60.2 (9.5) |

| #Breast reconstruction surgery (yrs: mean (SD)) | 54.4 (8.9) |

| Postcode | |

| Regional | 158 (31) |

| Metropolitan | 346 (69) |

| Missing data | 5 |

| Health system type | |

| Public | 132 (26) |

| Private | 372 (74) |

| Missing data | 5 |

| Laterality of surgery | |

| Unilateral | 379 (74) |

| Bilateral | 130 (26) |

| Lymph nodes removed | |

| Yes | 395 (78) |

| No | 114 (22) |

| Radiation treatment | |

| Yes | 337 (67) |

| No | 170 (33) |

| Missing data | 2 |

| Preexisting musculoskeletal issue ∗ | |

| Yes | 62 (12) |

| No | 447 (88) |

| Postoperative complication† | |

| Yes | 261 (51) |

| No | 339 (49) |

| Missing data | 1 |

- ∗Preexisting shoulder or torso injury reported. †Includes infections, seromas, necrosis, and other identified complications. #n = 76 (47%) (autologous breast reconstruction); n = 87 (53%) (implant-based).

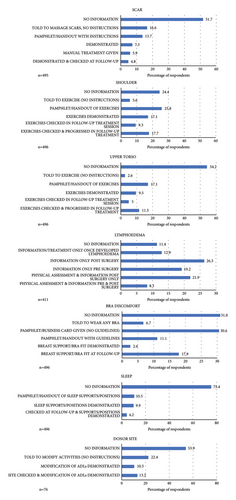

3.2. Delivery Method and Content of Physical Rehabilitation

Pamphlets and verbal instruction were the most common delivery methods; the least common were sessions where exercises, scar massage, breast support, and lymphedema were physically assessed and checked or progressed by a health professional (Figure 2). The proportion that received each delivery method varied for each adverse physical effect. For example, less than half of the respondents reported receiving any information about scars, torso, and donor site issues or physical discomfort disturbing sleep, whereas most respondents reported to have received information about lymphedema and shoulder issues (89% and 76%, respectively; Figure 2).

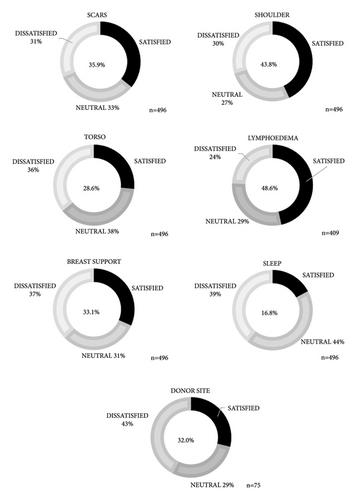

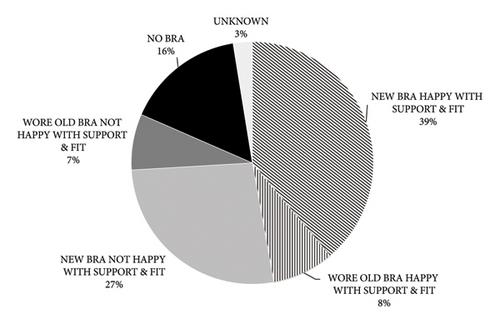

3.3. Level of Satisfaction

Variation was found in the satisfaction levels for each adverse physical effect (Figure 3); however, they were all less than 50%. The percentage satisfied was highest for lymphedema and shoulder issues (49% and 44%, respectively) and lowest for physical discomfort disturbing sleep (17%). Fifty percent of respondents were not happy with the fit and support of their bras, with 16% reporting they could not wear a bra (Figure 4).

3.4. Perceptions of Physical Rehabilitation

Three major themes that emerged from the thematic analysis of patient perceptions were (i) unaware of and unprepared for adverse physical effects; (ii) unsuitable information delivery; and (iii) insufficient follow-up.

3.4.1. Theme 1: Unaware of and Unprepared for Adverse Physical Effects

“My breast lymphedema became apparent eight months after radiation finished. It frightened the hell out of me because I thought the lumpiness was cancer returning. Huge scare!” (P444).

“I would have liked more information about the side effects of each treatment stage so that I could have been more prepared mentally” (P554).

“It would be good if healthcare professionals were able to alert patients to the potential for problems with scar pain, sleeping, bra discomfort etc. None of this was discussed with me and I just tried different remedies to help myself” (P299).

3.4.2. Theme 2: Unsuitable Information Delivery

“I had visits post-surgery in hospital, and I was very affected by pain killers. I don’t remember much about their advice then” (P309).

“Immediately post op there is so much information and hard to absorb and understand. This information needs to be continually provided …… not just be advised by the health professional and that box ticked and no further action taken. The mindset of the patient to understand and accept the information etc is not really understood” (P616).

“…follow up when relevant rather than convenient to health care. e.g., information about bras etc. does not sink in while you are waiting for pathology results” (P704).

“I was inundated with pamphlets, most of which I did not read” (P599).

“Pamphlets don’t cut the mustard. Too much info at once to a frightened patient about to lose an appendage is almost useless” (P580).

3.4.3. Theme 3: Follow-Up Was Insufficient

“They were great in hospital but then there was no further contact, which is when the problems became evident. …I did not know how to access the information I needed for the range of problems I experienced, particularly which professionals I needed” (P102).

“Often problems/questions can occur later but without good background knowledge a person isn’t quite sure what is normal or not normal” (P242).

“More physio intervention whilst in hospital rather than saying; ‘lift your arms-oh you will be fine.’ Cording and truncal and lymphedema prevention should be discussed. As should scar management and sleeping with specialist in field rather than surgeon saying: ‘you will need to massage the scar for the rest of your life,’ and surgeon dismissing pain on sleeping” (P604).

“I was in a private hospital, but they had no breast care nurses so there was simply no information given” (P391).

“A rehab program is available but at a venue approx. 60 km from where I live” (P281).

“The availability of a breast care nurse in my regional area would have been a great help, plus G.P.’s support and advice could have been better. I sourced my own private lymphedema specialist who I had to travel 3 hours to see” (P541).

“Providing more information about what is likely to happen after the surgery. I think I was in shock for about two weeks, and I didn’t really take in what I was being told immediately after the surgery. I didn’t even understand what I needed to know (because you don’t know what you don′t know)” (P622).

“More initial information and then actually following up on patients to see how they are coping would go a long way” (P58).

“Private patient I needed to source a lot of information myself…Developed lymphedema-didn′t have info regarding assessment prior to surgery this should be a must” (P685).

“ …make info available in different forms, e.g., verbal, written pamphlet, online and video” (P98).

“I found the most useful help came from physiotherapists (strength/flexion and lymphedema). I would like to see surgeons and oncologists work more closely with physios. Patients should be referred to appropriate practitioners ASAP” (P408).

“In a perfect world there would be big speciality allied services centres near every cancer care centre that could support physical health during and after cancer treatment” (P48).

4. Discussion

Consistent with our hypothesis and previous research [28, 32–37, 53, 54, 56, 61, 62], the needs of respondents were not perceived to be met by their physical rehabilitation, and only a low percentage were satisfied. The major perceptions of respondents were that they were unprepared for the adverse physical effects they experienced, the delivery method and timing of physical rehabilitation were unsuitable, and follow-up with health professionals was insufficient. These perceptions were supported and justified by quantitative data where a large percentage of the women received no information about their scars, torso, donor site issues, or how to manage physical discomfort disturbing sleep, and only a minority received a progressive rehabilitation program across the range of adverse physical effects experiences (Figure 2). Our discussion will propose causes why these perceptions occurred and expand on respondent recommendations of potential strategies for how physical rehabilitation could be improved within similar healthcare systems as Australia.

The perceptions of the lack of awareness, insufficient follow-up, and the small percentage of women who received any continuity of care with health professionals provide evidence that a coordinated multidisciplinary approach, where a team evaluates the sum of problems that a survivor faces (e.g., physical function) and plans a treatment program, was not the standard model of care delivered to these women over this 10-year period [11, 33, 40, 42, 45–48, 52, 59, 60, 65]. Therefore, prospective surveillance, survivorship care plans, and coordinated comprehensive rehabilitation had not been translated into many hospital systems across Australia, consistent with previous research [32, 33, 61, 62]. Consequently, breast cancer treatment-related physical conditions and preexisting physical morbidities, such as frozen shoulder or rotator cuff tears (common in the age group of the highest proportion of patients diagnosed with breast cancer [53, 66, 67]), were not assessed preoperatively or in follow-up appointments by surgeons or oncologists. This explains the limited awareness of respondents and referral to physical rehabilitation, and, in turn, the self-directed physical rehabilitation sought by respondents [32, 33, 62]. Miscommunication between doctors and patients is another barrier to access identified in the qualitative data [32]; respondents stated they did not commonly discuss their adverse physical effects with their surgeons or oncologists because the doctors had not asked about their physical function and identified the need for rehabilitation referral [32]. The focus of follow-ups with oncologists was cancer progression, and with surgeons’ wound healing and aesthetics, neither doctor focused on physical function.

Previous research has also found many doctors unaware of the adverse physical effects experienced [32, 33, 45], their common risk factors (e.g., axillary lymph node dissection, radiation, postoperative infection or seroma, cording, and preexisting musculoskeletal issues) [3, 6, 24, 26, 53, 68–71], or their effect on the ability to exercise and resume sport, work, and daily tasks [32, 45]. Other barriers to access to physical rehabilitation include lack of knowledge of established criteria to assess physical function and limited physical therapy resources with breast cancer-specific expertise to lead programs or be referred to [32, 40, 42, 45]. Indeed, respondents reported that physical therapy resources within the public system focused on treating lymphedema or were limited to a single postoperative in-patient visit following mastectomy surgery only. This would explain why scar, torso, donor site, bra, or sleep discomfort were the worst gaps in care. Lymphedema and shoulder issues were still a gap for a quarter of respondents, and limited and inconsistent surveillance was provided across Australia [32, 48].

- (1)

Increase patients′ awareness of potential functional morbidities and “plant the seed” that they can be alleviated or resolved through physical rehabilitation.

- (2)

Identify preexisting morbidities to prompt physical therapy referral and a proactive approach to physical rehabilitation.

- (3)

Collect evidence of the incidence and severity of adverse physical effects to educate doctors and healthcare providers on the need for physical rehabilitation.

A PROM, such as the Quick Dash [72], takes as little as 5 minutes to complete and provides a quantitative framework to enable patients and doctors to monitor physical recovery and progress. It also enables patients to identify whether professional intervention is needed and provides data for clinicians and patients to determine realistic time frames for physical recovery. Indeed, in the qualitative data, respondents reported being given unrealistic time frames for physical recovery. If a consistent PROM format was utilized, the occurrence and progression of adverse physical effects and efficacy of physical rehabilitation programs could be evaluated and compared amongst different health districts.

The qualitative data found poor perceptions of the timing and method of delivery because patients were inundated with pamphlets or verbal instructions immediately postsurgery when respondents were not emotionally or cognitively capable of absorbing information and asking questions. Consequently, many respondents lacked the knowledge to self-manage their adverse physical effects and identify if they needed professional assistance. The insufficient knowledge about the disease and planned treatment leading to dissatisfaction, lack of control, and poor quality of life was consistent with previous research [32, 53, 62, 65].

Respondents recommended a staged approach to improve the timing of physical rehabilitation delivery, beginning pretreatment with greater diversity in its delivery methods (i.e., videos, podcasts, and telehealth) [20, 50, 52–54]. Although there is a plethora of information available on the Internet on breast cancer recovery, respondents desired [62] up-to-date sources of information that directed them to a structured and progressive program to self-manage their physical recovery throughout their cancer trajectory [8, 20, 62, 65, 73]. That included expected and realistic milestones and alerts to enable them to determine when and where to seek professional assistance [62, 73]. Equipping women with the knowledge to effectively self-manage would promote proactive behaviours to manage adverse physical effects, enhance well-bearing and resilience, and limit wasted time and money spent self-managing without direction [8, 25, 32, 35, 36, 65].

Expanding from respondent recommendations, the authors propose a strategy to maximise access to physical rehabilitation with limited resources by delivering different levels of care depending on the patient’s needs, recommended in previous research [40]. The lowest level of care is a freely accessible, evidence-based, online education resource that provides consistent education to empower women to self-manage a range of common adverse physical effects, monitor their progress through milestones, and alert them when and where to seek professional intervention [32, 62]. Following respondent recommendations, the format would be multimodal (i.e., videos, podcasts, and written information). The online format would allow patient access at a time relevant to their needs at different stages of recovery, cognitive capacity, and geographical location [51, 52]. The second level would involve group sessions of physical rehabilitation delivered in-person or via telehealth for women who needed more assistance and motivation with their physical recovery [8]. The delivery method for the highest level of care would be one-on-one sessions with a physical therapist, reserved for women who had more severe and complex adverse physical effects, such as lymphedema [3, 50–52, 65]. However, such a model of care would require an RCT to confirm its efficacy and cost efficiency.

Improvements in physical rehabilitation are a worthwhile investment because of the health, quality of life, and financial costs of this gap in care [42, 45]. The PROM surveillance and three-level care model’s proposed intervention strategies provide a framework for a modest health system investment that has considerable potential benefits for patients, the health system, and the economy. Early intervention can prevent lymphedema and minimise its morbidity and cost [11, 37, 61]. Maximising sleep by addressing physical discomfort, particularly in the postoperative period, promotes physical and mental recovery [3, 20, 53, 65]. Addressing issues with breasts [32] enables women to be physically active and resume sport. Early intervention prevents adverse physical effects related to scars, shoulder, and torso issues from progressing into secondary issues from misuse or disuse, which are debilitating and costly to manage [14, 41, 47, 42, 45]. Relieving these issues [32] enables women to achieve the level of physical activity required to maximise health, limit breast cancer reoccurrence, and resume work, sport, and daily activities [4, 32], ultimately maximising the quality of life of patients living with breast cancer and benefiting the health system and the economy.

4.1. Limitations

Although this study provides a unique insight into patient perceptions linked to the content and delivery of physical rehabilitation, several limitations limit the generalisation of this research. The data were collected retrospectively and up to 10 years postsurgery. Therefore, respondent recall accuracy could have been affected. Over the 10 years, physical rehabilitation delivered and the surgical techniques used could also have changed. Ascertainment bias is another limitation, whereby women who were very satisfied and contented with their physical rehabilitation might not have volunteered to participate. It is also possible that women did receive physical rehabilitation but did not absorb or remember it. Finally, the physical rehabilitation received after each type of breast cancer surgery could have differed but was grouped together. We recommend further research to prospectively investigate physical rehabilitation education, treatment, and patient perceptions over a more limited period after surgery to support or refute the findings of the current study.

5. Conclusion

Women perceived that their physical rehabilitation did not prepare them for the adverse physical effects they experienced. The method and timing of delivery did not meet their needs at various stages of recovery, and the follow-up with health professionals was insufficient. Quantitative data on the content and delivery method supported these perceptions. Causal factors for the perceptions were examined, and recommendations were made to improve physical rehabilitation by using PROMs and a three-level model of care to spread the limited physical rehabilitation resources for maximal effect efficiently. Although many women recover from breast cancer, improved physical rehabilitation could enable women to manage the immediate or long-term side effects of breast cancer surgery and treatment [1, 72].

Additional Points

Key Points. (i) A high percentage of women are dissatisfied with their physical rehabilitation following breast cancer surgery and treatment. (ii) Women perceive they are not aware or prepared for the adverse physical effects they experience, the method and timing of delivery of physical rehabilitation does not meet their needs at various stages of recovery, and the follow-up with health professional is insufficient. (iii) Quantitative data on the content and delivery methods of physical rehabilitation support these perceptions. (iv) Strategies to enhance women’s experience and physical recovery are recommended.

Ethical Approval

The University of Wollongong Human Research Ethics Committee approved all data collection procedures (HE15/453).

Consent

Tacit consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Disclosure

The authors are responsible for correctness of the statements provided in the manuscript. This manuscript was submitted as a preprint in the link https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-265448/v1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

Deirdre McGhee and Julie Steele contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Deirdre McGhee. Anne McMahon and Deirdre McGhee analyzed the qualitative data. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Deirdre McGhee and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Breast Cancer Network Australia, Register4, and breast cancer groups (including Reclaim Your Curves) for supporting recruitment for this project. The authors also thank Jodi Steel for her invaluable contribution as a consumer advocate and Robyn Box, Hildegarde Reul-Hirche, and Sandi Hayes for their contributions to the survey development. This study was funded by the University of Wollongong, Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health. Open-access publishing was facilitated by the University of Wollongong, as part of the Wiley-University of Wollongong agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Open Research

Data Availability

Data will be made available on reasonable request.