Current Prospects of Husbandry and Breeding Practices of Chicken Populations Rearing in Rural Communities: For Sustainable Improvement Interventions

Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the present scenario of chicken husbandry and breeding practices in the rural districts of Sidama Region, southern Ethiopia. Four districts, namely Hula, Shebedino, Aleta Chuko, and Boricha were purposefully selected based on their chicken production potential and agroecological distinctiveness. The study data were collected from 161 chicken-keeping households through interviews, on-farm follow-ups, group discussions, and field observations. Descriptive statistics and indexed ranking procedures were applied to summarize the data using SAS software. The chicken farming system was predominantly free-scavenging, followed by slowly growing semi-intensive and few intensive farming systems. The majority of rural farmers were keeping chickens primarily to support family income and for home use. A decreasing flock size of indigenous chickens and an increasing trend of improved chicken distribution and rearing were observed. It has been noted that farmers have a good experience of selecting hatching eggs, breeding cocks, and hens. In highland districts, pure breeding is common, while in midland and lowland districts, crossbreeding is more common due to the high distribution of exotic breeds. In all study districts, chickens mainly rely on scavenging with minimal feed supplementation and sit on simple perches fixed in family houses and kitchens. More than 65% of farmers use various traditional medications that were known by farmers to cure sick chickens. Furthermore, the study identified seasonal feed shortages, disease outbreaks, unplanned breeding, limited management knowledge, predators, and drought as major bottlenecks to chicken production. Thus, these findings could raise guiding information to improve small-scale chicken husbandry and breeding practices, which help poor rural families, and the major bottlenecks to ensure sustainable poultry farming were identified. Moreover, the high mortality of chickens observed during peak dry and wet seasons in the Boricha and Hula districts, respectively, calls for further research on the adaptation potentials of chickens in their respective ecologies.

1. Introduction

In the tropics, rural poultry production is an important livestock subsector, with a higher share of indigenous stocks that are better climate-resilient and disease-resistant breeds compared to imported commercial strains [1–6]. In Ethiopia, there are about 56.06 million chickens, of which 88.2% are indigenous chickens [7], and that produce about 90% of the eggs and meat produced for rural households as a major source of home use and market sale [3, 8]. Furthermore, indigenous chickens in Ethiopia are gifted with high genetic variations and high adaptation ability, which is the basis for selective breeding and genetic improvement strategies [9–11].

However, due to the small flock size and low outputs obtained from indigenous chickens, farmers pay little attention to overall management care, insufficient extension, and low attention paid to improvement interventions [6, 12–14]. The previous attempt to improve the low productivity of indigenous chickens through the distribution of exotic chicken breeds has resulted in low success in Ethiopia, particularly in rural settings [11, 15, 16]. In some areas, it has caused severe genetic dilution, a high inbreeding rate, and neglect of climate-resilient and disease-resistant indigenous chickens [5, 17, 18]. Furthermore, besides genetic improvement, husbandry practices like feeding, housing, healthcare, and the effectiveness of extension services could potentially determine the production potential of chickens under smallholder farmers [6, 19–23].

Moreover, the current changes in global climatic conditions, such as fluctuations in environmental temperature and humidity, greatly influence animal feed and water availability, cause seasonal disease outbreaks, and alter the overall production system. Besides, the rises in market demand for animal products, population growth, and urbanization have significantly impacted the stability of the existing poultry production systems, particularly in the tropics [5, 24, 25]. Thus, periodically assessing and identifying the production systems, production objectives, and prevailing problems in particular production circumferences are important for sustaining smallholder chicken husbandry practices. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the current prospects of chickens’ breeding and husbandry practices in rural settings in the Sidama region of Ethiopia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Areas

This study was conducted in four rural districts, namely Shebedino, Boricha, Aleta Chuko, and Hula of Sidama regional state, southern Ethiopia. The study districts were selected purposefully based on their chicken production potential and agroecological distinctiveness. Accordingly, Shebedino is located at 6°44′ to 6° 84′ N and 37° 92′ to 38° 60′ E with an altitude range of 1146–1350 m above sea level and partly rooted in the Great Rift Valley. This district represents midland agroecology with moderate temperatures ranging from 16 to 25°C and receives a mean annual rainfall of 1170 mm. Boricha district is the second district, which is situated at 6°46′N to 7°01′N longitude and 38°04′E to 38°24′E latitude. It has mainly the dry lowland, which accounts for 78% of the total land area coverage and typically represents a lowland agroecology with warmer temperatures and lower rainfall. The third district is Aleta Chuko, with the geographical location extends from 6° 46′N to 7° 01′N and 38° 04′E to 38° 24′E. It has an altitude of 1750–2300 m above sea level. For this study, Aleta Chuko is also considered a midland agroecology with annual mean temperature ranges from 18 to 28°C and mean rainfall of 1250 mm. The fourth district is Hula, which typically represents highland agroecology, which is characterized by cooler temperatures and higher rainfall with altitudes ranging from 2759 to 2829 m above sea level. The total indigenous chicken populations of the selected districts were Aleta Chuko has 158,420 chickens; Shebedino district has 156,625; Boricha district has 66,874; and Hula district has 59,830 chickens. The descriptions of the study districts and indigenous chicken populations were obtained from the Sidama Regional State Bureau of Agriculture and Livestock and Fishery Development for the 2023 fiscal year annual report (unpublished).

2.2. Data Collection Protocols

Multistage purposive sampling techniques were applied to select the study subjects. In the first stage, four districts were purposefully selected based on their chicken production potential and agroecological distinctness. In the second stage, based on the same criteria, three kebeles from each district were selected purposefully. In the third stage, a total of 161 households who possess at least five adult chickens and have at least 5 years of experience in chicken farming were purposefully selected and interviewed with a semi-structured questionnaire. Accordingly, 45 households from Hula, 38 from Shebedino, 43 from Boricha, and 35 households from Aleta Chuko district who keep indigenous and improved chickens (Sasso breeds and their crosses with indigenous chickens) were involved in the study. Chicken flock size and dynamics, farmers’ purpose of chicken farming, breeding, feeding, housing, and health management practices of chickens were assessed through interviews. The interviews were conducted at the farmers’ houses with the assistance of local agricultural extension officers. Out of the 161 households, 60 households participated in on-farm follow-ups on basic management and breeding practices in addition to the interviews. Moreover, farm observations and monitoring, as well as group discussions with experienced farmers, veterinarians, and extension workers, were conducted to obtain further information on feed shortage and disease outbreak seasons, common traditional medications, breeding and selection strategies, trends of chicken flock dynamics, and changes in chicken production systems.

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Chicken Production Systems

As presented in Table 1, the majority (78.5%) of farmers practice a free-scavenging system of chicken farming, followed by a semi-intensive system (18%), and the remaining few farmers exercise intensive chicken farming. In all districts, there was a growing practice of semi-intensive production systems for exotic chicken breeds. Moreover, in Boricha and Shebedino districts, few private limited cooperatives, youth and women, were practicing small-scale intensive chicken farming. In these two districts, there was access to and distribution of improved chicken breeds from government and non-governmental organizations. As a result, these districts had a relatively better tendency in terms of constructing good shelters for chickens, supplementing mixed rations, practicing better health management, and maintaining larger flock sizes, which are characteristics of an intensified farming system.

| Management system | Districts (%) | Overall | X2 | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hula | Boricha | Shebedino | Aleta Chuko | ||||

| Free-scavenging | 86.7 | 72.1 | 71.0 | 85.3 | 78.5 | 2.70 | 0.85 |

| Semi-intensive | 13.3 | 20.9 | 21 | 14.7 | 18.1 | ||

| Intensive | — | 7.0 | 8 | 3 | 4.4 | ||

3.2. Chicken Flock Size and Breed Population Dynamics

Table 2 presents the indigenous chicken flock size of households, cock-to-hen ratio, and trend of flock dynamics within 5–10 years of the study districts. Accordingly, the indigenous chicken holdings ranged from 7 to 13 chickens. Significantly (p < 0.05), higher chicken flock size was observed in the Boricha district. Likewise, a higher proportion of layers, in addition to chicks, were recorded in all districts. The cock-to-hen ratio observed in the study districts ranged from 1:4.5 to 1:5.8. Moreover, it has been found that, within a 5- to 10-year interval, the distribution of exotic breeds has been significantly increasing. Except in the Hula district, the trend of farmers’ indigenous chicken holdings was decreasing in all other districts, while the trend of exotic chickens was showing an increasing trend (Table 2).

| Flock size and age structure | Districts (mean ± S.D.) | Overall | F-value | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hula (highland) | Boricha (lowland) | Shebedino (midland) | Aleta Chuko (midland) | ||||

| Total chicken holding | 7.80c | 12.3a | 10.4b | 10.70b | 10.31 | 6.45 | 0.012 |

| Chicks (up to 8 weeks) | 2.1b ± 0.6 | 4.0 a ± 1.1 | 3.7ab ± 0.3 | 3.4b ± 0.7 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 4.76 | 0.003 |

| Pullet (8 weeks to 1 year) | 1.3b ± 0.7 | 2.0a ± 0.7 | 1.5b ± 0.6 | 1.6ab ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 1.24 | 0.033 |

| Cockerels (8 weeks to 1 year) | 1.0c ± 0.4 | 1.4a ± 0.8 | 1.2b ± 0.6 | 1.3b ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 4.80 | 0.003 |

| Cocks | 0.5 ± 0.03 | 0.9 ± 0.7 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 2.27 | 0.083 |

| Hens | 3.0b ± 0.4 | 4.1a ± 0.5 | 3.4ab ± 1.2 | 3.5b ± 0.9 | 3.5 ± 0.8 | 8.42 | <0.001 |

| Hen-to-cock ratio | 5.8:1 | 4.5:1 | 5.6:1 | 5:1 | 5.2:1 | — | — |

| Trend of chicken flock size within 5–10 years | |||||||

| Indigenous chickens | ↔ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | — | — | — |

| Exotic breeds | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | — | — | — |

- Note:a, ab, b, cMeans with different superscript letters between districts are significantly different at 5%. ↓ Refers to the decreasing trend of a breed type in the districts. ↔ Refers to no difference recognized. ↑ Refers to the increasing trend of a breed in the districts.

Households in all districts raise more improved chickens (Table 3) than indigenous chickens (Table 2). Moreover, Shebedino, Aleta Chuko, and Boricha districts have higher improved chicken flock sizes than the highland (Hula) district due to better introduction of exotic chickens to midland and lowland locations of the Sidama region. Likewise, a large number of improved chickens reared in all districts were chicks, followed by pullets and hens. It has also been observed that the improved chickens’ cock-to-hen ratio was also substantially higher than that of the indigenous chickens (Tables 2 and 3).

| Flock size and age structure | Districts (mean ± S.D.) | Overall | F-value | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hula (highland) | Boricha (lowland) | Shebedino (midland) | Aleta Chuko (midland) | ||||

| Total chicken holding | 9.0c | 13.6ab | 13.9a | 12.6b | 13.2 | 6.45 | 0.005 |

| Chicks (up to 8 weeks) | 2.3b ± 1.0 | 4.3ab ± 0.7 | 4.4a ± 1.1 | 3.2b ± 0.5 | 3.6 ± 0.8 | 4.76 | 0.045 |

| Pullet (8 weeks to 1 year) | 2.7b ± 0.7 | 3.1a ± 0.9 | 3.3a ± 0.4 | 3.4ab ± 0.7 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 1.24 | 0.039 |

| Cockerels (8 weeks to 1 year) | 1.2c ± 0.8 | 1.5ab ± 0.02 | 1.6a ± 0.3 | 2.0b ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 4.80 | 0.003 |

| Cocks | 0.8c ± 0.1 | 1.6a ± 0.5 | 1.2b ± 0.1 | 1.4b ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 2.27 | 0.001 |

| Hens | 2.0b ± 0.7 | 3.0a ± 1.0 | 3.4a ± 0.2 | 2.8b ± 0.7 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 8.42 | 0.018 |

| Hen-to-cock ratio | 2.5:1 | 1.8:1 | 2.8:1 | 2:1 | 2.1:1 | — | — |

- Note:a, ab, b, cMeans with different superscript letters between districts are significantly different at 5%.

3.3. Purpose of Chicken Keeping

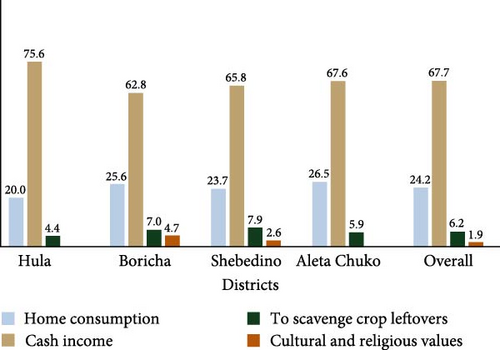

The reported purposes of keeping chickens in the study districts were for home consumption, source of cash income, and for social and religious services (Figure 1). In all districts, keeping chickens as a source of income was considered a primary choice, followed by home consumption. Since chickens were particularly owned by young children and women, eggs, and chickens were sold in local markets to cover the cash needs of households. Moreover, few farmers (1.9%) use chickens for cultural and religious services. For instance, white roosters were sacrificed as an expression of best wishes, and black or darker chickens were slaughtered to protect the family from any sorcery or curse. The summary of survey data from the study households revealed that chickens reared in the Hula and Aleta Chucko districts do not have cultural or religious values. Moreover, about 6.2% of farmers keep chickens for the purpose of feeding crop aftermath during harvesting seasons and scavenging kitchen wastes.

3.4. Breeding Practices

3.4.1. Mating Practices and Source of Breeding Stock

The predominant mating system of chickens in the study districts was pure breeding (49.4%), followed by crossbreeding (30.4%), and a combination of both (21.2%), as presented in Table 4. A significantly (p < 0.001) higher proportion (57.8%) of farmers in the Hula district were practicing pure breeding. However, in all other districts, 29%–37% of farmers practice crossbreeding. Likewise, about half of the studied households use their neighbors’ cocks (53.4%) for mating, and the remaining farmers use their own cocks. While doing so, farmers prioritize heavy and well-built, double-combed, and plumage colors other than pure white or pure black cocks when selecting cocks for mating.

| Breeding practices | Districts (%) | Overall | X2 | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hula | Boricha | Shebedino | Aleta Chuko | ||||

| Mating systems | 40.6 | 0.001 | |||||

| Pure breeding | 57.8a | 46.5b | 44.7b | 42.8b | 49.4 | — | — |

| Crossbreeding | 26.7b | 30.2ab | 28.9ab | 37.2a | 30.4 | — | — |

| Both | 15.6c | 23.3ab | 26.3a | 20.0b | 21.2 | — | — |

| Source of breeding cock | 3.47 | 0.324 | |||||

| Own flock | 37.8 | 46.5 | 47.4 | 57.1 | 46.6 | — | — |

| Neighbor cock | 62.2 | 53.5 | 52.6 | 28.9 | 53.4 | — | — |

| Source of breeding stock | 5.16 | 0.523 | |||||

| Own flock | 55.6 | 51.2 | 55.3 | 54.3 | 54.0 | — | — |

| Purchased from local market | 26.7 | 37.2 | 18.4 | 27.7 | 27.3 | — | — |

| Purchased from rearing farms (exotic stocks) | 17.8 | 11.6 | 26.3 | 20 | 18.7 | — | — |

| Strategies to break broodiness in hens | 8.66 | 0.731 | |||||

| Remove sitting nests | 33.3 | 32.6 | 39.5 | 34.3 | 34.1 | — | — |

| Hange on perches | 11.1 | 16.3 | 7.9 | 11.4 | 11.8 | — | — |

| Pour water into the nest | 24.4 | 27.9 | 23.7 | 28.6 | 26.0 | — | — |

| Put hens in neighbors’ home | 13.3 | 18.6 | 18.4 | 14.3 | 16.1 | — | — |

| Others ∗ | 17.8 | 4.7 | 10.5 | 11.4 | 11.2 | — | — |

- Note:a, ab, b, cValues with different superscript letters between districts are significantly different at 5%.

- ∗Refers to inserting feathers into hen’s nostrils, tying a sound-producing plastic on hen’s tail, and chasing hens away from the brooding nests.

In all study districts, the main source of replacement stock was the progeny of their own flock (>50%), while 18.4%–37.2% of farmers purchase foundation stocks from local markets, and 11.6%–26.3% of farmers purchase replacement stock from cooperatives’ rearing farms, respectively. As part of breeding management practices, farmers have several traditional strategies through which the broodiness behavior of hens can be broken. Most importantly reported were removing sitting nests, pouring water into sitting nests, and moving hens to a neighbor’s home. Additionally, a few farmers also hang hens on perches, insert a feather into the hen’s nostril, and tie sound-producing plastic material on the hen’s tail feather to disturb and forget the behavior of the broodiness. Farmers revealed that when doing so, hens stop broodiness and leave their sitting nest within 4–5 days. The observed broodiness-breaking strategies of farmers across districts are presented in Table 4.

3.4.2. Selection Criteria of Hatching Eggs and Breeding Chickens

Ranked choices of farmer’s selection criteria for hatching eggs, breeding hens, and cocks are presented in Table 5. Accordingly, egg size, the hen’s own performance, the hen’s pedigree, and egg shape were ranked as guiding criteria to select a good hatching egg in order of importance. Moreover, farmers have good indigenous knowledge of not incubating eggs laid in the first and last 4–5 days of a clutch. As justified by farmers, the earliest eggs have been resulting in smaller chicks, and the later leads to late hatching, so these eggs are removed from incubation by broody hens. Moreover, farmers perceive that eggs are not hatched as normal chicks if handled by bare hands. Thus, they rub their hands with ash or cover eggs with a clean cloth before handling them.

| Traits | Farmer’s choice | Index | Rank | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | |||

| Hatching eggs | |||||||

| Egg size | 83 | 60 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0.30 | 1 |

| Egg shape | 25 | 30 | 31 | 29 | 45 | 0.19 | 4 |

| Hen own performance | 72 | 41 | 32 | 15 | 0 | 0.27 | 2 |

| Hen pedigree history | 52 | 41 | 38 | 16 | 13 | 0.24 | 3 |

| Breeding hen | |||||||

| Egg production (size and number) | 118 | 33 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0.13 | 1 |

| Laying pattern | 58 | 41 | 51 | 7 | 3 | 0.105 | 4 |

| Body size | 72 | 42 | 22 | 11 | 13 | 0.108 | 3 |

| Wing size and feather cover | 38 | 31 | 28 | 22 | 41 | 0.081 | 10 |

| Pedigree history | 55 | 43 | 33 | 29 | 0 | 0.102 | 5 |

| Fertility rate | 46 | 49 | 26 | 22 | 17 | 0.092 | 7 |

| Broodiness and mothering behavior | 41 | 36 | 40 | 31 | 12 | 0.091 | 8 |

| Comb type | 42 | 50 | 31 | 35 | 2 | 0.097 | 6 |

| Plumage color | 29 | 44 | 39 | 22 | 26 | 0.086 | 9 |

| Hardness/adaptability | 67 | 45 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 0.11 | 2 |

| Breeding cock | |||||||

| Growth rate | 80 | 46 | 15 | 19 | 0 | 0.17 | 2 |

| Body size and conformation | 105 | 51 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0.20 | 1 |

| Plumage color | 51 | 37 | 31 | 21 | 20 | 0.14 | 4 |

| Comb type | 44 | 41 | 24 | 24 | 27 | 0.13 | 5 |

| Mating behavior | 37 | 30 | 22 | 28 | 43 | 0.12 | 6 |

| Hardiness/adaptability | 57 | 45 | 28 | 20 | 10 | 0.15 | 3 |

Regarding hen selection, egg production, particularly egg size, and number, was ranked first, followed by hardness or adaptability, body size, egg laying pattern, pedigree performance, comb type, fertility rate, broodiness and mothering ability, plumage color, and wing feather coverage, in order of their importance. Moreover, traits such as hens’ feather cover and good sitting behavior have implications for better hatching, and brooding characteristics were important criteria for hen selection. Furthermore, red, brown, and a mixture of multiple-colored hens were preferred, but pure black and white hens were disliked. Double- and large-combed hens are more preferred than single- and rudimentary-combed hens.

On the other hand, breeding cocks were selected based on multiple economic and visual criteria; primarily, body size and conformation, vigorous growth at cockerel age, hardness, plumage color, comb type, and mating behavior were considered by farmers. Accordingly, cocks that have a larger body size and good conformation, a vigorous growth rate, adaptability to harsh production conditions, a double and large comb, and a red or multicolored plumage color are most preferable. Black or white plumage-colored and single-combed cocks have low market value, so such chickens were hardly liked by most farmers in all districts.

3.4.3. Culling of Chickens From Flocks

There was no significant (p > 0.05) difference between the culling practices applied by farmers in all districts (Table 6). The majority (90%) of farmers practice culling chickens for various reasons, but the remaining were not culling chickens. Accordingly, low egg production, small body size, slow growth rate, and unwanted plumage color (pure black or darker and pure white) were the most important reasons for culling chickens from a flock. About 4.7%–8.9% of farmers cull chickens due to poor pedigree performance, poor hatching behavior, and feather or vent pecking behavior. The selling of chickens (84.4%) was the predominant method of culling. Moreover, culling by selling chickens was also practiced during feed shortages and heavy rainy seasons.

| Culling practices | Districts (%) | Overall | X2 | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hula | Boricha | Shebedino | Aleta Chuko | ||||

| Do you practice culling? | |||||||

| Yes | 91.1 | 88.4 | 89.5 | 91.4 | 90 | 0.21 | 0.975 |

| No | 8.9 | 11.6 | 10.5 | 8.6 | 10 | — | — |

| Reasons for culling | |||||||

| Low egg production | 26.7 | 23.3 | 23.7 | 22.8 | 24.2 | 9.06 | 0.989 |

| Slow growth rate | 20 | 18.6 | 15.8 | 14.3 | 17.4 | — | — |

| Small in body size | 15.6 | 18.6 | 26.3 | 22.8 | 20.5 | — | — |

| Poor pedigree performance | 8.9 | 4.7 | 7.9 | 8.6 | 7.4 | — | — |

| Poor brooding behavior | 6.7 | 7 | 5.3 | 5.7 | 6.2 | — | — |

| Unwanted plumage color | 8.9 | 9.3 | 13.2 | 14.3 | 11.2 | — | — |

| Aggressiveness/pecking behavior | 6.7 | 4.7 | — | 5.7 | 4.3 | — | — |

| Others | 6.7 | 14 | 7.9 | 5.7 | 8.7 | — | — |

| Culling method applied | |||||||

| Selling | 86.7 | 83.7 | 81.6 | 85.8 | 84.4 | 1.22 | 0.976 |

| Slaughtering at home | 4.4 | 7 | 5.3 | 2.8 | 5.0 | — | — |

| Avoiding eggs for hatching | 8.9 | 9.3 | 13.2 | 11.4 | 10.6 | — | — |

3.5. Chicken Feed Resources and Feeding

The most predominant feeding system for chickens in all districts was scavenging with supplementation (>93%) (Table 7). Although the amount and type of supplemental feed vary across seasons and districts, almost all households practice supplementing their chickens. Accordingly, among the cereal grain supplements, maize grain was predominantly offered to chickens in a higher proportion in the Boricha, Shebedino, and Aleta Chuko districts, while barley was mostly offered in the Hula district. Purchased feed supplements, such as milling byproducts (wheat bran), and purchased rations were most commonly offered in Boricha, Shebedino, and Aleta Chuko districts due to the high proportion of improved chickens in the farmer’s flock. Kitchen wastes, byproducts of locally processed human food leftovers such as kocho and bula (a white product extracted from local processing of enset [Ensete ventricosum]), were supplemented in all districts in almost equal proportions. Wheat grain was supplemented with a minimal amount due to its high purchasing cost.

| Feeding practices | Districts (%) | Overall | X2 | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hula | Boricha | Shebedino | Aleta Chuko | ||||

| Feeding options | |||||||

| Scavenging-only | 6.7 | 4.7 | 2.5 | 5.7 | 5.0 | 0.76 | 0.858 |

| Scavenging with supplementation | 93.3 | 95.3 | 97.5 | 94.3 | 95.0 | — | — |

| Supplementary feeding resources | |||||||

| Maize grain | 13.3b | 30.2ab | 31.6a | 29.4ab | 26.1 | 35.5 | 0.024 |

| Barley | 15.6a | 0.0b | 0.0b | 0.0b | 3.9 | ||

| Frushika | 8.9a | 16.3a | 13.2a | 14.7a | 13.3 | ||

| Kitchen leftover | 33.3a | 16.3c | 26.3b | 26.5b | 25.6 | ||

| Maize powder soaked with water | 4.4c | 9.3b | 13.2a | 10b | 9.2 | ||

| Enset byproduct, Kocho, and other leftovers | 11.1a | 4.7c | 5.3c | 8.8b | 7.5 | ||

| Milling by product | 4.4c | 14.0a | 7.9b | 11ab | 9.3 | ||

| Wheat | 8.9a | 9.3a | 2.6b | 0.0b | 5.2 | ||

| Supplementation frequency for adult chickens | |||||||

| Once | 37.8 | 33.3 | 34.2 | 34.3 | 34.8 | — | — |

| Twice | 48.9 | 61.9 | 65.8 | 60.0 | 58.4 | 6.73 | 0.347 |

| Three times | 13.3 | 7.1 | — | 5.7 | 6.8 | — | — |

| Feeding equipment | |||||||

| Throw on ground | 88.9 | 86 | 81.6 | 80.0 | 84.5 | — | — |

| Plastic sheet | 4.4 | 9.3 | 10.7 | 8.6 | 8.1 | 3.01 | 0.807 |

| Plate (plastic tray or wooden) | 6.7 | 4.7 | 7.9 | 11.4 | 7.5 | — | — |

| Severe feed scarcity months | June to October | January to March | June to August | June to August | — | — | — |

| Feed shortage alleviation strategies | |||||||

| Stop supplementing | 57.8 | 51.2 | 47.4 | 42.8 | 50.3 | — | — |

| Purchase milling byproducts | 15.6 | 25.6 | 21.1 | 17.1 | 20.0 | — | — |

| Purchase grains or commercial feed | 8.9 | 14.0 | 18.4 | 25.7 | 16.1 | 7.11 | 0.625 |

| Reduce flock size by selling | 17.7 | 9.3 | 13.2 | 14.4 | 13.6 | — | — |

| Do you offer clean water to your chickens? | |||||||

| Yes | 95.6 | 100 | 92.1 | 97.1 | 95.7 | 5.47 | 0.461 |

| No | 4.4 | 0 | 7.9 | 5.9 | 4.3 | — | — |

| What is the main source of water for chickens? | |||||||

| River water | 88.9 | 90.7 | 84.2 | 91.2 | 88.2 | — | — |

| Pipe water | 4.4 | 9.3 | 7.9 | 5.9 | 6.8 | 2.92 | 0.558 |

| Any source consumed during scavenging | 6.7 | 0 | 7.9 | 5.9 | 5.0 | — | — |

- Note:a, ab, b, cValues with different superscript letters between districts are significantly different at 5%.

Almost all farmers have the practice of providing water to their chickens every day. Most commonly, river water is offered to chickens, while few farmers use pipe water, and others leave chickens to drink water when scavenging from any source. There is no practice of using standard feeding and watering troughs for chickens in all districts. The majority (84.5%) of the farmers offer feed to chickens through throwing it on the ground, using trays (7.5%), and using plastic sheets for soft and soaked feeds. Some of the plastic and plate trays used by farmers to provide feed to chickens are displayed in Figure 2a–c.

3.6. Chicken Housing Practices

Most farmers (81.4%) have no separate shelter, and chickens share the same house with family (Table 8). Perches fixed in family houses (32.5%) and in kitchens (22.3%), separate houses outside the family house (19.3%), and simple shelters attached to family houses (26.0%) were the most common chicken house types observed in the study districts. However, the housing practices did not significantly (p > 0.05) vary across districts. As shown in Figure 3a–f, households often use wood perches along with houses made of wood with mud, bamboo, wood made with iron sheets, or grass-covered houses. Moreover, as a good practice, about half of the studied farmers have various types of laying nests for hens. Old clothes and soft materials like dry enset (Ensete ventricosem) leaf, hay, straw, jars, and old carpets were used by farmers to set up a laying nest (Figure 4b). A few farmers made mud nest boxes (Figure 4c). In Hula, Shebedino, and Aleta Chuko districts, farmers use an oval-shaped material (Figure 4a) made of bamboo as a laying nest and brooding for newly hatched chicks until they are able to sit on perches.

| Housing practices | Districts (%) | Overall | X2 | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hula | Boricha | Shebedino | Aleta Chuko | ||||

| House for chickens | 1.13 | 0.769 | |||||

| Separate | 15.6 | 23.3 | 15.8 | 20.0 | 18.6 | — | — |

| Sharing the same house with owners | 84.4 | 76.7 | 84.2 | 80.0 | 81.4 | — | — |

| Observed housing types | 4.60 | 0.868 | |||||

| Perches fixed within family houses | 42.2 | 30.2 | 28.9 | 28.6 | 32.5 | — | — |

| Perches in kitchens | 24.4 | 20.9 | 23.7 | 20 | 22.3 | — | — |

| Separate wooden house outside | 15.6 | 23.3 | 21.1 | 17.1 | 19.3 | — | — |

| Shelter attached to family house | 17.8 | 25.6 | 26.3 | 34.3 | 26.0 | — | — |

| Reasons to have a separate chicken house | 2.78 | 0.972 | |||||

| Small flock size and require small space | 53.3 | 51.1 | 50 | 45.7 | 50.5 | — | — |

| Tradition of housing chickens with human | 17.8 | 16.3 | 23.7 | 22.8 | 19.8 | — | — |

| To prevent from climate stress | 20 | 18.6 | 15.8 | 14.3 | 17.3 | — | — |

| To safeguard from thieves/predators | 8.9 | 14.0 | 10.5 | 17.2 | 12.4 | — | — |

| Laying nest for hens | 3.73 | 0.293 | |||||

| Supplied | 44.4 | 62.8 | 47.4 | 45.7 | 50.3 | — | — |

| Not supplied | 55.5 | 37.2 | 52.6 | 54.3 | 49.7 | — | — |

| Feeders and drinkers for chickens | 1.56 | 0.668 | |||||

| Provided | 80 | 74.4 | 89.5 | 82.8 | 81.5 | — | — |

| Not provided | 20 | 25.6 | 10.5 | 17.2 | 15.5 | — | — |

Figure 4a is the cone-shaped bamboo-made material that is used for laying and brooding purposes. In the 1st picture (the upright), farmers put old clothes or any soft material inside it, and hens would sit to lay and incubate eggs. In the 2nd picture (turn down), in this position during day or night, newly hatched chickens dwell under it (for brooding purposes).

Figure 4b shows an indigenous hen incubated Sasso hen’s eggs on a nest made from old clothes. Figure 4c shows a mud-made individual laying nest for chickens in the Boricha district.

3.7. Health Management Practices

Chickens’ health-related management practices were summarized and presented in Table 9. Accordingly, all farmers reported that there had been illness conditions and deaths of chickens in their flocks in the past 12 months. Across the study districts, there was a significant (p < 0.05) difference in the season of disease occurrence and the causes of chicken death. In Hula district, most (88.9%) disease outbreaks and the death of chickens have been commonly observed during the wet season. While in the Boricha district, the illness and death of chickens occurred during the dry season. Moreover, due to feed shortages caused by erratic rainfall distribution, high chicken mortality was observed during peak dry months (mid-December through mid-February) in the district. However, in the Shebedino and Aleta Chuko districts, disease outbreaks have been reported almost uniformly during both wet and dry seasons due to the relatively optimized weather conditions in the midlands.

| Healthcare management practices | Districts (%) | Overall | X2 | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hula | Boricha | Shebedino | Aleta Chuko | ||||

| Season chickens get sick more frequently | 38.69 | 0.001 | |||||

| Wet | 88.9a | 23.3c | 57.9b | 57.1b | 57.1 | — | — |

| Dry | 11.1c | 76.7a | 43.1b | 42.9b | 42.9 | — | — |

| Knowledge about chickens’ disease sources | 0.07 | 0.995 | |||||

| Yes | 17.8 | 16.3 | 18.4 | 17.1 | 17.4 | — | — |

| No | 82.2 | 83.7 | 81.6 | 82.9 | 82.6 | — | — |

| Treatment of diseased chickens | 1.26 | 0.974 | |||||

| Using traditional treatment | 66.7 | 65.1 | 65.8 | 68.6 | 66.5 | — | — |

| Take to veterinary clinics | 6.6 | 11.6 | 10.5 | 5.7 | 8.7 | — | — |

| Do nothing | 26.7 | 23.3 | 23.7 | 25.7 | 24.8 | — | — |

| Reasons for adult chicken illness and death | 24.78 | 0.003 | |||||

| Lack of vaccination and shortage of veterinary services | 55.5 | 46.5 | 71 | 62.8 | 59.6 | — | — |

| Feed shortage and weight loss | 22.2b | 28a | 23.7b | 22.8b | 24.3 | — | — |

| Extreme hot and/or cold weather | 13.1b | 25.6a | — | — | 10.5 | — | — |

| Poor hygiene | 8.9a | — | 5.3b | 8.4a | 7.4 | — | — |

| Main sources of chick mortality | 4.19 | 0.898 | |||||

| Disease | 15.5 | 14.0 | 26.3 | 25.7 | 18.0 | — | — |

| Predator | 53.3 | 60.5 | 47.4 | 45.7 | 70.0 | — | — |

| Accident/mechanical death | 8.9 | 7.0 | 55.3 | 8.4 | 7.4 | — | — |

| Poor brooding | 22.2 | 18.5 | 21 | 20 | 20.5 | — | — |

- Note:a, b, cValues with different superscript letters between districts are significantly different at 5%.

Furthermore, the majority (82.6%) of farmers do not have sufficient knowledge of the exact cause of a particular disease in their chicken flocks. It has been reported that high disease outbreaks and deaths of chickens across the study districts were mainly due to a lack of vaccination and shortage of veterinary services (59.6%), poor body condition (24.3%), hot or cold weather conditions (10.5%), and poor hygiene (7.4%). A higher proportion (66.5%) of households use traditional treatment options; however, few farmers (8.7%) take their diseased chickens to government or private clinics, and the rest leave chickens untreated. Commonly reported traditional treatment materials used by farmers were garlic juice, lemon juice, local herbs, and different parts of plant materials in grinded or raw form in mixtures with drugs like tetracycline, ash soaked with water, or salt. Some farmers also give food oils and butter in mixtures with other treatments and are given with feed, water, or alone. In all districts, predators (70%) are reported to be the main source of chick mortality, followed by poor brooding, disease, and accidents. Moreover, farmers reported a variety of predators, such as hawks, baggers, wild and domestic cats, dogs, and eagles.

Farmers recognize the diseased chickens based on the following general illness symptoms: sudden death, inactivity, dullness, closed eyes, unusual discharges from the mouth, nose, and eyes; abnormal droppings or diarrhea; loss of feathers; skin lesions; paralysis (neck twisting; leg and wing paralysis); abnormal sitting (lying down on the haunches); discolorations of the head, wattle, and comb; abnormal walking; and any local swelling and related symptoms. In addition to the symptoms mentioned by farmers, the district’s veterinarians mentioned that common chicken diseases such as Newcastle disease, pneumonia, avian influenza, and fowl pox occur mainly during dry seasons (December, January, February, and mid-March), whereas infectious bursal disease (Gumboro), fowl cholera, salmonellosis, fowl typhoid, coccidiosis, and other unrecognized diseases are common and occur during wet seasons (April, July, August, September, and October). As stated by farmers and veterinarians, Newcastle disease, pneumonia, and fowl typhoid were the most commonly reported diseases of chickens in all districts.

4. Discussion

As found in our study and reports of other studies, the share of semi-intensive and intensive farming systems in rural settings did not show significant expansion when compared with its long attempt to transform the predominant scavenging system. In addition, previous efforts, such as extension services and capacity-building trainings continually delivered to rural farmers by many organizations, have not impacted more in this regard. However, in urban and peri-urban areas, the intensive and semi-intensive production systems are better at expanding.

The observed higher chicken holding in the Boricha district might be due to the suitability of a warmer climatic condition that favors hatching and brooding processes used to build a larger flock size. Moreover, the better adaptability potential of chickens to lowland areas, where water and feed shortages are common for large ruminants, might be another reason farmers focus on chicken rearing. Similarly, Gebremariam, Mazengia, and Gebremariam [27] reported that higher chicken holding was observed in lowland areas than in highland and midlands in southern Tigray, Ethiopia. In addition, the higher proportion of layers obtained in this study was due to farmers keeping chickens mainly for egg production and rarely selling hens unless they are poorly productive. Moreover, the observed higher flock sizes in families with low-income status and more children were due to children and women using the sales of their chickens for an immediate family cash need. Likewise, Hailemicael et al. [28] and Alemayehu et al. [12] reported that indigenous chickens under smallholder farmers are mainly owned and managed by women and children. Similarly, in the tropics, women and children who spend most of their time around the homestead are the main owners and caregivers of indigenous chickens [29–31].

Due to the massive distribution of exotic chickens to improve the livelihood of rural families in the Shebedino, Boricha, and Aleta Chuko districts, the population of indigenous chickens was reducing. It has also been noticed that, in infrastructure-accessible areas, the proportion of improved chickens is rapidly increasing. In the proximity of urban and peri-urban areas, almost all farmers possess exotic chickens with two or three local chickens among a flock size of 10–15 chickens. On the other hand, in these districts, the future effect of genetic dilution due to indiscriminate crossbreeding should be given due attention.

The obtained indigenous chicken flock size (7–13 chickens) of this study is in agreement with a report by Habte et al. [32]: 7–10 mature birds per household in Ethiopia under a scavenging system; Emebet et al. [33], who reported on average 4.85 chickens per household in southern Ethiopia. However, Feleke and Tadesse [34] reported slightly higher flock holdings (14 ± 1.6 chickens for Bako Tibe and 6 ± 0.6 chickens for Dano districts in the Oromia region) than the current finding. Similarly, Negassa, Melesse, and Banerjee [35] reported similar average flock size per household of 10.3, 14.1, and 11.2, respectively, in the high-, mid-, and lowland agroecological zones of the Southeastern Oromia region of Ethiopia. The observed chicken holding variation among studies might be due to the availability of resources for chicken rearing, climatic conditions, and breed preferences of farmers.

The higher average cock-to-hen ratio obtained in this study suggested that there is no shortage of breeding cocks in the village flocks. Similarly, farmers most frequently raise both male and female chickens for fattening and egg production, which accounts for the increased cock-to-hen ratio (1:2.1) observed in improved chickens. Furthermore, several studies recommended the ideal male-to-female ratio to obtain good fertility and hatchability rates in chicken flocks. For instance, Habte et al. [32] recommended 1:7–12 hens to produce more fertile eggs for hatching; Appleby, Hughes, and Elson [36] recommended a mating ratio of 1:14–16 and 1:10–12 for exotic layers and broiler breeders, respectively; and Wilson [37] proposed mating ratios of 1:12–1:15 for light breeds and 1:10–1:12 for heavy breeds. However, in tropical chickens, Iyasere et al. [38] suggested a mating ratio of 1:9 for farmers where chickens are raised in a free-ranging system. Similarly, McGary, Estevez, and Bakst [39] reported that a mating ratio of 1:9 can yield satisfactory results in terms of fertile eggs as long as the cock is sexually competent and healthy. In another study, Chotesangasa [40] reported the lowest egg fertility in chickens with a mating ratio of 1:16 compared to that obtained in 1:8 and 1:12 in Thai native chickens. Moreover, a higher ratio cannot result in higher fertility; rather, it leads to high cock competition and fighting and a higher percentage of infertile eggs [41].

In agreement with this finding, Melesse and Negesse [42], Chala [43], Feleke and Tadesse [34], Korato, Hankamo, and Abebe [44], and Tilahun, Mitiku, and Ayalew [21] reported that chickens were kept for home consumption and as a source of income from the sale of eggs and live chickens, which were the primary objectives of chicken farming for all rural farmers in Ethiopia. Similarly, in tropical countries such as Rwanda, India, Kenya, and Tanzania, indigenous chickens contribute to food security, cash income, and socio-cultural roles for rural families. Accordingly, in Rwanda, 72% of households sell chickens and eggs for household income [45]. In India, indigenous chickens are vital for animal protein and socio-cultural life [46]. In Kenya, poultry is kept for home consumption, and the cleansing of spirits is mediated using indigenous chickens [47]. Ngongolo and Chota [48] reported that chicken production provides increased household income, employment, food source, esthetic value, manure, and spiritual value in Tanzania. Furthermore, Passarelli et al. [49] reported that backyard chicken production systems have been promised as a nutrition-sensitive strategy in low-income settings due to their potential for increasing income, improving consumption of nutritious foods, and empowering women. Similarly, in Southern Africa, Mtileni et al. [50] reported that indigenous chickens are used in witchcraft to foretell the future and are prescribed by traditional healers to treat illnesses and avert misfortunes.

The significantly higher proportion of farmers practicing pure breeding in the Hula district was due to the low distribution of exotic chickens in the communities. However, in all other districts where the Sasso chicken breed was introduced, there is unintentional crossbreeding. Moreover, under scavenging production systems, both hens and cocks run together, and thus uncontrolled mating is predominantly practiced, which is consistent with the observation of Chala [43], who reported that indiscriminate mating of cocks and hens without any control is common when flocks scavenge together.

While selecting breeding cocks, farmers prioritize heavy and well-built, rose-combed, and plumage colors other than pure white or pure black cocks for mating purposes. This was due to farmers’ assumptions that single-combed hens were poor egg producers, whereas white and colorful hens were susceptible to predators and evil eyes. Similar perceptions have been reported by Gebremariam, Mazengia, and Gebremariam [27] and Tilahun, Mitiku, and Ayalew [21] for different local chicken ecotypes in Ethiopia. Furthermore, besides the number and size of eggs, farmers consider the laying patterns and the pedigree history of hens while selecting quality hatching eggs, which is in agreement with the report of Muchadeyi et al. [51]. Furthermore, during breeding, farmers avoid using white plumage because it exposes chickens to predator attacks [52]. Consistent with the current study, Mahoro et al. [53] in Rwanda; Asmelash, Dawit, and Kebede [54], and Feleke and Tadesse [34] in Ethiopia reported that farmers of different areas focus on the production of a high number of eggs, good body size, growth rate, reproductive performance, comb shape, and better brooding ability when selecting hens and cocks for breeding.

Similar to our findings, Getachew et al. [55] in the Gambella region of Ethiopia reported that the predominantly indigenous chicken feeding system was characterized by free-scavenging with seasonal supplementations. Likewise, almost all farmers in Gurage Zone, central Ethiopia, practiced scavenging with additional supplementation and scavenging-only feeding systems for local chickens [21]. Furthermore, in Western Kenya, 99% of households left chickens to scavenge with minimal supplementation as the main practice of feeding Wambui, Njoroge, and Wasike [56]. Similarly, scavenging, household waste, kitchen leftovers, and industrial byproducts were the major feed resources of indigenous chickens’ [43]. Moreover, Padhi [46], Habte et al. [32], and Mahoro et al. [53] reported that chickens scavenge around the homestead areas during the day, eat kitchen waste, leftover cereals like rice, wheat, pulses, green grass, and any available feedstuff, and produce a good-quality, cheap source of animal protein.

In addition, the growing demand for meat chickens and eggs in rural and urban markets is encouraging farmers to supplement chickens with additional feed to harvest more products. The same was reported by other authors in Ethiopia [12, 55]. However, the quantity and type of feed available for scavenging chickens showed a wide variation among seasons and agroecologies. For instance, in all study districts, off-harvesting seasons are feed-deficit times. During this time, the majority of farmers cope by reducing flock size through the sale of less productive birds, avoiding using supplementary feed, preventing the hens from sitting on the eggs and purchasing additional feed. Moreover, farmers explained that laying and brooding hens and young chicks were preferentially supplemented during this time. It has been reported during focal group discussions with farmers and extension workers that a severe feed shortage of chickens occurs from June to October in the Hula district, from January to March in the Boricha district, and from June to August in Shebedino and Aleta Chuko districts. Concentrate and mixed rations were preferably fed to newly hatched chicks, brooding, and laying hens.

In line with the current finding, Tilahun, Mitiku, and Ayalew [21] in Gurage Zone, Chala [43] in Guder Town, Oromia Region, reported that chickens have no separate houses and share a common house with family. Moreover, the authors reported that perches fixed in family houses and kitchens, simple shade attached to family houses, small separate shelters, and houses in baskets made up of wood were the common chicken housing strategies of farmers in different agroecologies. Furthermore, Wambui, Njoroge, and Wasike [56] reported that chickens were managed as a single flock with no separation of the different ages and sexes, and 65% of farmers used the kitchen to house the birds in Kenya. Moreover, as observed by the current survey, Chala [43], Habte et al. [32], and Dessie, Abebe, and Alebachew [23] also reported that chickens are housed with family due to small flock sizes, lack of awareness, shortage of land, and construction materials.

Regarding the health management conditions, the reported higher proportion of chicken illness and deaths during wet seasons in the Hula district (highland) could be due to the fact that during the rainy season, there is high parasitic proliferation due to high moisture and contamination of scavenging resources, which could lead to high risk of chicken ailments. However, in Boricha, during the dry season, there is a recurrently high ambient temperature, and chickens are highly affected by respiratory-related diseases due to the high dust. On the other hand, in the Shebedino and Aleta Chuko districts, the occurrence of diseases during both wet and dry seasons was almost uniform. The observed lack of vaccination and shortage of veterinary services in this study were similarly reported by Hailegebreal et al. [57] in the Sidama region. Furthermore, Ouma et al. [58] reported that poultry diseases are often not properly diagnosed, and vaccination programs can be difficult to implement in such systems due to limited veterinary extension services, challenges in maintaining a cold chain to keep vaccines viable, and unreliable vaccine production and distribution in resource-limited rural settings.

In agreement with this study, higher mortality of chickens in northwest Ethiopia occurred due to improper nutrition, substandard hygienic conditions, and a lack of an appropriate disease prevention and control program [59]. During discussions with farmers and extension workers, most farmers believed that traditional treatments have better curing power than modern drugs when applied by experienced farmers (mainly women). Similarly, traditional treatment strategies using local herbs and different homemade preparations were common practices used to treat diseased chickens in almost all parts of Ethiopia. Accordingly, Chala [43] in Guder town, Oromia region, reported that farmers used lemon and a traditional home-distilled alcoholic drink, “Areke,” by adding it to chicken feed and water. Gebremariam, MAzengia, and Gebremariam [27] reported that alcohol (areke), Holy soil (Emenet), lemon juice, Feto, hot pepper, and garlic were used by farmers in southern Tigray. Nebiyu, Berhan, and Kelay [60] reported that farmers treat diseased chicken using tobacco leaf, lemon juice, and cooking oil administered with drinking water in the Halaba zone. Moreover, Desta and Wakeyo [61] reported that a mixture of garlic and tetracycline with butter, garlic juice, rue (tena adam), limon with cassava leaf, and cassava leaf alone were offered to diseased birds in the Wolaita zone. Similarly, in India [62] and in Southern Zambia [63], farmers use traditional herbs such as Aloes vera, Azadirachta indica (neem), Mululwe (Cassia abbreviata/Singueana, Trema Orientalis) to treat diseased chickens.

Similar to our observations, several authors reported that wild birds and hawks cause the highest losses during the dry season, while the most dangerous predator during the rainy season is the wild cat. Domestic and wild cats, dogs, rats [60, 64], foxes, and hawks [60] are reported to be the main predators that attack chickens under the local production conditions. The dense vegetation cover at farmyards where chicks scavenge together with hens that favor the hiding of predators has worsened predatory attacks on chicks in all districts.

Regarding chicken diseases, Wubet et al. [65] reported that Newcastle, salmonellosis, fowl cholera, coccidiosis, and fowl pox were reported as the main infectious diseases that cause high morbidity and mortality in both indigenous chickens and large-scale farms in Bishofitu, Ethiopia. Newcastle Disease, Infectious Bursal Disease, Fowl Typhoid, and Coccidiosis were the most important diseases identified through longitudinal studies in the selected districts of the Sidama region [57]. Similarly, Kebede, Melaku, and Kebede [66] reported New Castle disease as the most reported disease, followed by coccidiosis, fowl pox, and ectoparasitism in northern Gondar, northwest Ethiopia. Likewise, Melesse and Negesse [67] reported that Newcastle disease, fowl cholera, coccidiosis, fowl influenza, fowl pox, and salmonella were the main diseases of chickens in 13 zones of southern Ethiopia. Similarly, Mujyambere et al. [68] reviewed that in East Africa, the indigenous chicken production system was constrained by disease burdens such as Newcastle, Gumboro, and Ecto-endo parasites. Mpenda et al. [69] and Simbizi et al. [70] also reported that Newcastle, Gumboro, coccidiosis, respiratory infections, and fowl pox are known to cause high chicken mortality in various parts of Africa. In Tanzania, Sindiyo and Missanga [71] reported that Newcastle causes up to 100% mortality in backyard chickens.

5. Conclusion and Future Research Areas

The study revealed that free-scavenging was a predominantly practiced chicken farming system in the study districts, implying that the long-term development and extension services delivered by several organizations to transfer this system have not adequately impacted it as expected. The overall management practices such as breeding, feeding, housing, and healthcare conditions were considered substandard, which limits the productive potential of both indigenous and improved chickens. Moreover, farmers’ indigenous knowledge applied in selecting breeding stocks and care of hatching eggs, use of traditional medications, selective culling of less productive chickens during feed-deficit times, and experience of not hatching chicks during harsh production conditions can be considered as best practices. Therefore, the current scenario, such as shifting of breed composition from indigenous dominant to exotic chickens, growing intensive production systems due to market conditions, changes in management practices, and indigenous knowledge of farmers during breeding stock selections, could be a valuable input while designing a suitable chicken improvement strategy that is compatible with rural setups. We recommend the observed serious feed shortage during heavy rains in highlands, prolonged dry months and cropping seasons in lowlands, an outbreak of various chicken diseases, unplanned introduction and crossbreeding of exotic chickens, and climate change impacts on chicken farming would be considered to set a sustainable chicken production in the study areas. Furthermore, the best indigenous experiences on chicken management practices exercised by farmers and the high mortality of chickens during peak rainy and dry seasons should be investigated by further research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

C.C., S.B., and A.M. contributed to conceptualization, data curation, methodology, software, and data analysis. C.C. contributed to investigation, original draft preparation, and writing–review and editing. S.B., A.S., and A.M. contributed to resources, validation, visualization–review and editing. All authors have read and agreed on the content of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Hawassa University Office of Research and Technology Transfer Vice President for the partial research support. The authors would like to express their deep appreciation to all chicken owners in all districts for their active involvement and cooperation during on-farm monitoring and survey work. We are also thankful to field assistants from all districts and district office experts for their kind cooperation.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request by the corresponding author.