Construction of a Novel Doxorubicin Nanomedicine Using Bindarit as a Carrier: A Multiscale Computer Simulation-Assisted Design-Based Study

Abstract

Nanomedicines typically use polymeric materials or liposomes as carriers. This provides targeting advantages but may lead to a series of defects, such as low drug loading, high risk in terms of safety, and high production costs. Herein, we report a computer simulation-assisted designing method for the construction of a novel doxorubicin (DOX) nanomedicine without any polymer carriers. We used a small molecular drug, bindarit (BIN), as a carrier of DOX to provide synergistic antitumor effects. First, the intermolecular forces between DOX and BIN were calculated for evaluating the interaction and potential conformation of the DOX/BIN complex. Then, the potential assembly ability of the DOX/BIN complex was predicated here by using dissipative particle dynamic stimulation. These computational simulation results suggested that BIN could form an amphiphilic complex with DOX through π–π stacking, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic interaction and then self-assemble to nanoaggregates at the mesoscopic scale. Under the computational guidance, doxorubicin/bindarit nanoparticles (DOX/BIN NPs) in a spherical morphology were successfully prepared, and these NPs possess the original cytotoxic activity of DOX. Thus, this multiscale computer simulation-assisted design strategy can serve as an effective approach to develop nanomedicines using small molecules as a carrier.

1. Introduction

Chemotherapy is a widely used strategy for the treatment of tumors. Traditional chemotherapeutic drugs usually have evident disadvantages such as toxicity to normal cells, poor precision, and multidrug resistance [1]. Currently, an increasing number of traditional chemotherapeutic drugs are prepared as nanomedicines, which provides improved antitumor efficiency and reduced side effects, compared to the drugs alone [2]. These nanomedicines are usually prepared with a large amount nonactive excipients as carriers, such as liposomes [3, 4], polymers [5], and inorganic nanoparticles [6]. However, the use of these excipients as basic materials for the formation of nanomedicines may lead to several problems, such as low drug loading, high risk in terms of safety, and high production costs [7]. These limitations negatively impact the prospects of these nanomedicines in clinical use. Therefore, researchers are committed to developing strategies to reduce the proportion of inactive substances in nanomedicines through supramolecular assembly and other approaches, to achieve higher drug loading, increased drug safety, and simpler preparation methods.

In our previous study [8], we successfully engineered a paclitaxel (PTX) nanoaggregate without any inactive excipients, using the small active molecule, indomethacin, as a carrier [9]. Compared to nanomedicines using polymers or other inactive excipients as carriers, this PTX nanomedicine showed natural advantages in drug loading and safety. Similar to PTX, doxorubicin (DOX) is an effective and extensive chemotherapeutic drug; however, its toxicity poses a significant clinical challenge [10]. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for clinical use having a safer profile but at a much higher cost than the common DOX injection [11, 12]. Although numerous novel DOX nanomedicines have been developed, most of them are facing obstacles for clinical application based on the excipients. Bindarit (BIN) is a classic inhibitor of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 [13], which can reduce the infiltration of tumor-associated macrophages to inhibit tumor progression and metastasis [14–17]. BIN and DOX are polyaromatic compounds with a carboxyl group and an amino group, respectively [18]. They have strong intermolecular forces because of hydrogen bonds and π–π stacking. Notably, BIN is a potentially appropriative drug carrier for DOX; however, whether BIN possesses the ability to load DOX remained unknown.

In recent years, computer-aided technologies such as molecular docking and molecular dynamics have been widely applied in the screening and design of new drugs, by predicting the intermolecular interactions between drugs and targets, and the conformation of drug-target complex [19–21]. However, the application of these computer-aided technologies in designing nanomedicines is still in its infancy. In our previous studies [8], we have successfully employed these computer-aided technologies for analyzing the intermolecular forces driving the assembly of nanomedicines.

Herein, we hypothesize that these computer-aided technologies can also be used in designing nanomedicines. Taking BIN and DOX as model drugs, a computer simulation from the atomic to the mesoscopic scale was designed and successfully utilized to engineer a novel DOX nanomedicine using BIN as a carrier. Under the computer-aided guidance, DOX/BIN NPs with inherited antitumor activity from DOX were successfully prepared.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Computer Simulation Methods

2.1.1. AutoDock

The molecular formulas of DOX and BIN were downloaded from DrugBank (https://www.drugbank.ca/) and optimized through geometry optimization in Materials Studio 2017 software (Accelrys Inc.). In AutoDock 4.2 [22], the optimized molecular conformation of BIN was imported as a ligand, and the optimized molecular conformation of DOX was imported as a macromolecule. The grid box was set to 126 Å × 126 Å × 126 Å, and the distance of each small grid point was 0.0375 nm. Lamarckian GA [23], a genetic algorithm, simulated annealing algorithm, and local search algorithm were used for calculations, and all other parameters remained unchanged, by default.

2.1.2. DPD Simulation

First, DOX, BIN, and water molecules were set to the corresponding beads (D, B, and W, respectively) in Materials Studio 8.0. The Flory–Huggins interaction parameters between these beads were calculated using the Blends module. According to the formula αij(ρ = 3) = 25 + 3.50 · χ2, the results are summarized in a table as the parameters of the DPD simulation [24].

After the mesoscopic molecules were constructed, a mesoscopic model of DOX, BIN, and water molecules was built at a DOX/BIN/water ratio of 1 : 1 : 8. To optimize the mesoscopic model, we first created a force field using the DPD method with a length scale of 6.46 Å and a mass scale of 54 amu and then replaced the values of the DPD simulation parameters. After the mesoscopic model was optimized, DPD simulations were performed for 50 ns. After the DPD simulations, the molecular distances between the core of DOX/BIN NPs and DOX, BIN, and water was calculated using the radial distribution function.

2.2. Preparation of DOX/BIN NPs

2.2.1. Materials

DOX was purchased from Seebio (Shanghai, China). Bindarit (BIN) was obtained from Nanjing Chemlin Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). Dialysis members were purchased from Repligen (Boston, MA, USA).

2.2.2. Preparation of Hydrophobic DOX

Doxorubicin hydrochloride was dispersed in ultrapure water with ten equivalents of triethylamine, the solution was continuously stirred overnight at 4°C in the dark, and hydrophobic doxorubicin was obtained after drying.

2.2.3. Preparation

2.3. Characterization of DOX/BIN NPs

The distribution of particle zeta-potential and the diameter of the NPs were measured using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS instrument (Malvern, UK). Ultraviolet spectra were recorded using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (TU-1810, Beijing, China). Fourier transform infrared spectra (FT-IR) were measured using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (VERTEX-70, Bruker, Germany). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observations were performed using a Tecnai-10 microscope (Philips, Netherlands). All samples were examined at 20°C–25°C.

2.4. Cytotoxicity Assays

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Intermolecular Forces between DOX and BIN

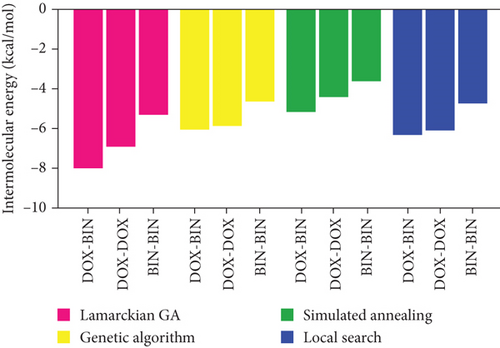

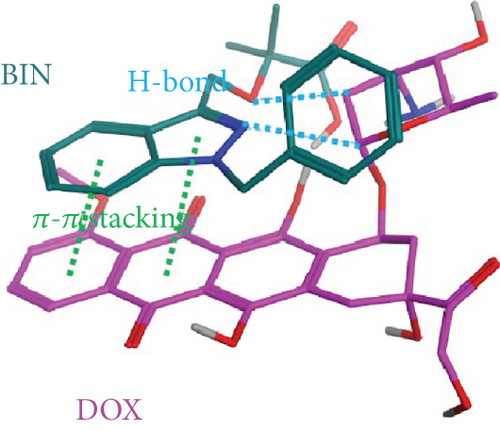

It is well known that a strong intermolecular interaction is the key to the formation of stable intermolecular complexes. Thus, the interactions between DOX and BIN were initially calculated using AutoDock 4.2. As shown in Table 1, according to Lamarckian GA, the intermolecular energy was -8.03 kcal/mol, which was contributed by van der Waals forces (Vdw) and hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) between DOX and BIN. The results of the other three algorithms (genetic algorithm, simulated annealing algorithm, and local search algorithm) were similar. Mediated by this strong intermolecular interaction between DOX and BIN, a stable BIN/DOX complex was formed after BIN docking to DOX. Subsequently, the interactions between DOX and DOX as well as BIN and BIN were calculated. As shown in Tables 2 and 3, according to Lamarckian GA, the intermolecular energy was -6.94 kcal/mol and -5.29 kcal/mol for DOX-DOX and BIN-BIN, respectively, both interactions less than that between DOX and BIN. As shown in Figure 1, the result suggested that DOX tended to combine with BIN rather than itself.

| Lamarckian GA | Genetic algorithm | Simulated annealing | Local search | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding energy | -5.94 | -3.97 | -3.05 | -4.22 |

| Intermol energy | -8.03 | -6.06 | -5.14 | -6.31 |

| Vdw | -6.08 | -4.57 | -4.58 | -4.64 |

| Electrostatic energy | -1.95 | -1.49 | -0.56 | -1.67 |

| Ligand efficiency | -0.25 | -0.17 | -0.13 | -0.18 |

| Inhibit constant | 44.47 | 1.22 | 5.84 | 810.18 |

| Total internal | 1.21 | 1.26 | -0.83 | -1.42 |

| Torsional energy | 2.09 | 2.09 | 2.09 | 2.09 |

| Unbound energy | 1.21 | 1.26 | -0.83 | -1.42 |

| H-bond | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Lamarckian GA | Genetic algorithm | Simulated annealing | Local search | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding energy | -3.64 | -2.56 | -1.11 | -2.81 |

| Intermol energy | -6.93 | -5.84 | -4.39 | -6.09 |

| Vdw | -6.51 | -5.59 | -4.34 | -5.70 |

| Electrostatic energy | -0.41 | -0.25 | -0.05 | -0.39 |

| Ligand efficiency | -0.09 | -0.07 | -0.03 | -0.07 |

| Inhibit constant | 2.13 | 13.31 | 152.69 | 8.75 |

| Total internal | -6.22 | -5.74 | -3.63 | -4.20 |

| Torsional energy | 3.28 | 3.28 | 3.28 | 3.28 |

| Unbound energy | -6.22 | -5.74 | -3.63 | -4.20 |

| H-bond | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Lamarckian GA | Genetic algorithm | Simulated annealing | Local search | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding energy | -3.20 | -2.51 | -1.51 | -2.63 |

| Intermol energy | -5.29 | -4.6 | -3.6 | -4.72 |

| Vdw | -5.23 | -4.37 | -3.59 | -4.62 |

| Electrostatic energy | -0.07 | -0.22 | 0.00 | -0.1 |

| Ligand efficiency | -0.13 | -0.1 | -0.06 | -0.11 |

| Inhibit constant | 4.48 | 14.52 | 78.53 | 11.71 |

| Total internal | -1.54 | -1.54 | -0.75 | -0.83 |

| Torsional energy | 2.09 | 2.09 | 2.09 | 2.09 |

| Unbound energy | -1.54 | -1.54 | -0.75 | -0.83 |

| H-bond | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

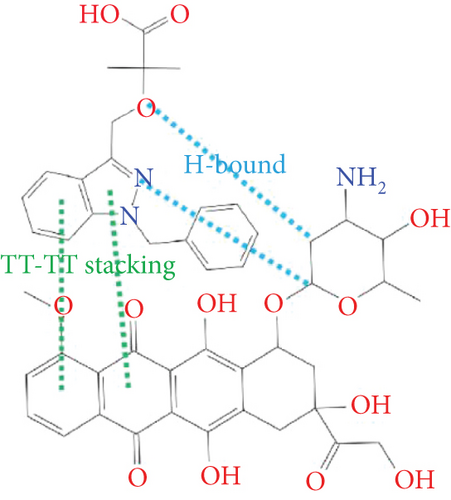

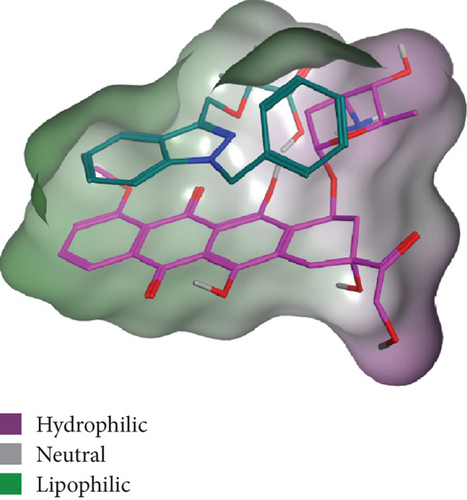

As shown in Figure 2, the intermolecular interactions between DOX and BIN were mainly composed of π–π stacking interaction and H-bonds. The π–π stacking interaction was attributed to the conjugated aromatic groups in DOX and BIN, while H-bonds were contributed by the hydroxyl group in DOX and the carboxyl group in BIN. Additionally, through the hydrophilic and hydrophobic surface rendering of the DOX/BIN complex, we can clearly see that the BIN/DOX complex shows an obvious amphiphilic property. The amino group of DOX and the carboxyl group of BIN constitute the hydrophilic region, while conjugated aromatic groups constitute the main hydrophobic region (Figure 2).

The Blends module in Materials Studio software 8.0 is widely used to calculate the intermolecular compatibility, and it can also be used to calculate the interaction parameters for performing DPD mesoscopic simulation. In the Blends module, the mixing energy between the same molecules was set to 0 kcal/mol. As shown in Table 4, after calculation, the mixing energy between DOX and BIN was 1.533 kcal/mol, which is much lower than the mixing energy of 52.426 kcal/mol between DOX and water and 10.768 kcal/mol between BIN and water. The compatibility between DOX and BIN is therefore much better than that between DOX and water, as well as that between BIN and water. In a Blends system of DOX, BIN, and water, DOX and BIN would combine with each other to form a complex because of their common hydrophobic properties. This is a very important basis for the formation of DOX/BIN NPs.

| Energies | DOX-BIN | DOX-DOX | DOX-water | BIN-BIN | BIN-water | Water-water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 (298 K) | 1.533 | 0 | 52.426 | 0 | 10.768 | 0 |

| Emix (298 K) | 0.908 | 0 | 31.046 | 0 | 6.377 | 0 |

| Ebb avg (298 K) | -14.95 | -14.95 | -14.95 | -7 | -7 | -1.655 |

| Ebs avg (298 K) | -10.73 | -14.95 | -2.076 | -7 | -2.438 | -1.655 |

| Ess avg (298 K) | -7 | -14.95 | -1.655 | -7 | -1.655 | -1.655 |

| Ebb min | -15.854 | -15.854 | -15.854 | -9.036 | -9.036 | -2.638 |

| Ebs min | -12.06 | -15.854 | -4.885 | -9.036 | -4.762 | -2.638 |

| Ess min | -9.036 | -15.854 | -2.638 | -9.036 | -2.638 | -2.638 |

| Ebb avg | -2.615 | -2.615 | -2.615 | -1.682 | -1.682 | -0.077 |

| Ebs avg | -2.106 | -2.615 | -0.537 | -1.682 | -0.435 | -0.077 |

| Ess avg | -1.682 | -2.615 | -0.077 | -1.682 | -0.077 | -0.077 |

| Ebb max | 2.336 | 2.336 | 2.336 | 5.269 | 5.269 | 3.388 |

| Ebs max | 3.638 | 2.336 | 4.966 | 5.269 | 5.228 | 3.388 |

| Ess max | 5.269 | 2.336 | 3.388 | 5.269 | 3.388 | 3.388 |

| Zbb | 5.577 | 5.577 | 5.577 | 5.531 | 5.531 | 5.509 |

| Zbs | 6.088 | 5.577 | 12.171 | 5.531 | 11.748 | 5.509 |

| Zsb | 5.122 | 5.577 | 2.473 | 5.531 | 2.644 | 5.509 |

| Zss | 5.531 | 5.577 | 5.509 | 5.531 | 5.509 | 5.509 |

3.2. The Simulation of the Assembly of DOX and BIN in Water

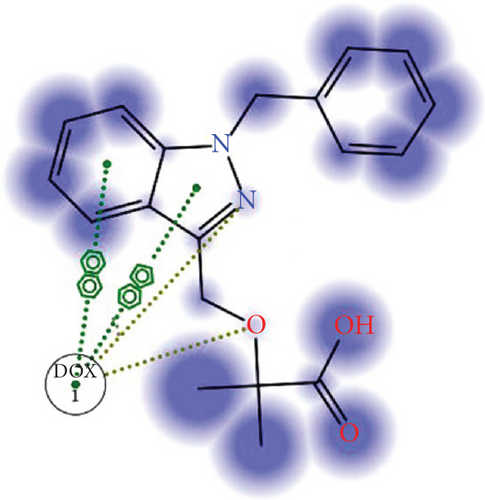

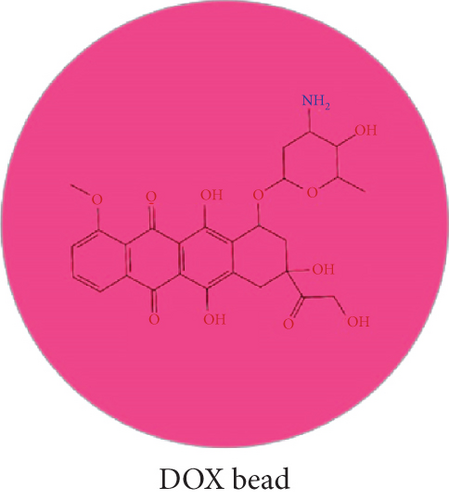

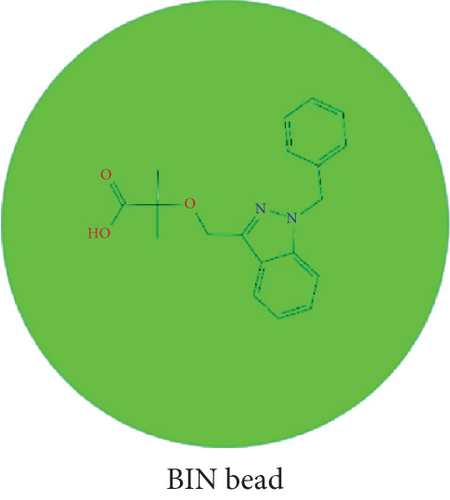

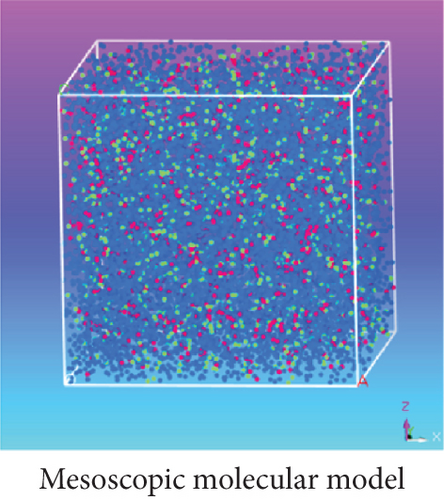

Based on the calculated mixing energy, the Flory-Huggins parameters (χ2) between molecular pairs were obtained simultaneously. Then, the DOX, BIN, and water molecules were coarse-grained to the corresponding beads (Figure 3).

As shown in Table 5, according to the formula αij(ρ = 3) = 25 + 3.50 · χ2, the DPD repulsion parameter αij was achieved and applied to build a DPD force field. Based on this DPD force field, a mesoscopic molecular model was constructed with beads of DOX, BIN, and water at the DOX/BIN/water ratio of 1 : 1 : 8, and its conformation was further optimized. In the initial mesoscopic model, DOX, BIN, and water beads were randomly distributed in the simulated lattice (Figure 3).

| Energies | χ2 (298 K) | αij |

|---|---|---|

| DOX-BIN | 1.533 | 30.364 |

| DOX-water | 52.426 | 208.492 |

| BIN-water | 10.768 | 62.69 |

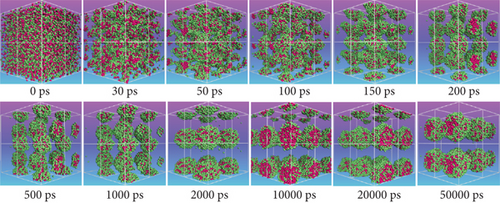

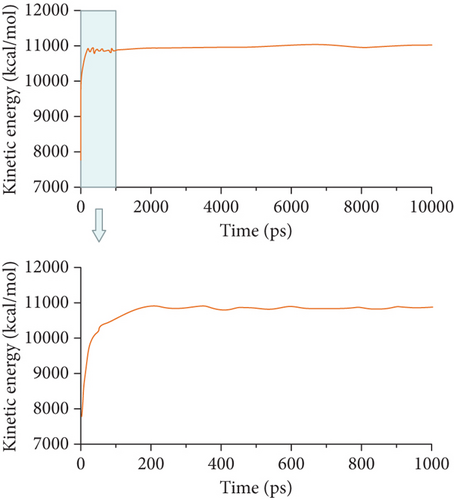

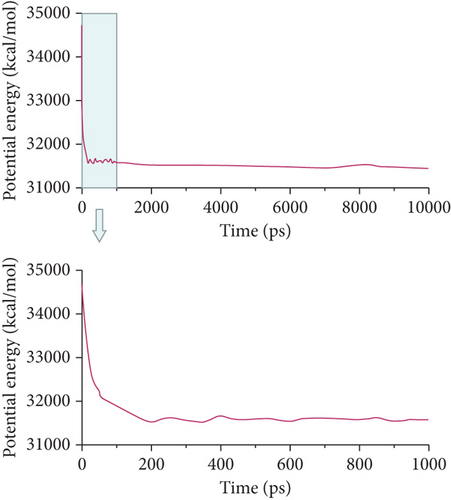

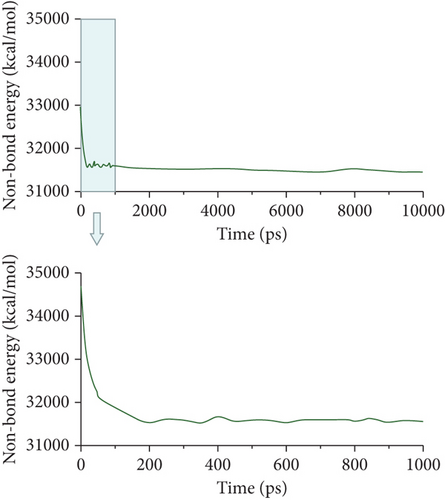

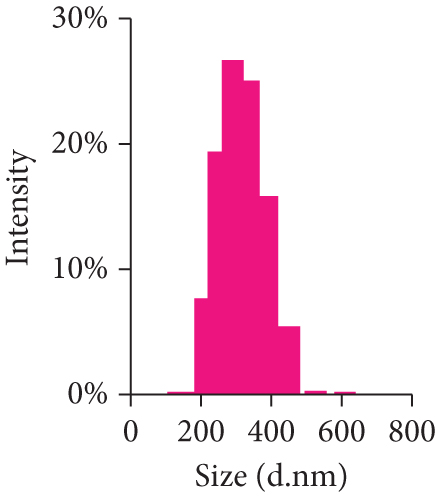

Then, the DPD mesoscopic simulation [24] was performed using the DPD module in Mesocite for 50 ns to display the assembly process of DOX/BIN NPs. As shown in Figure 4, the DOX beads and BIN beads gradually changed from the randomly distributed state to small aggregates during 0-200 ps. These small aggregates first formed a core of DOX, following which BIN was gradually distributed to its surface. At this time, the kinetic energy increased sharply, while the theoretical energy and the nonbond energy decreased (Figures 4(b)–4(d)). Then, the aggregates gradually assembled into spheres during 200-1000 ps, and all the energy fluctuated at its baseline. Finally, stable spherical aggregates were formed, and this structure was maintained from 1000 to 50000 ps. All the energy remained stable from 1000 to 10000 ps.

Because BIN is more hydrophilic than DOX, the cross-section of the stable spherical aggregates revealed that the DOX beads were mainly packed in the core, while the outer layer was primarily distributed with BIN beads (Figure 5). This was further confirmed by the calculation of the molecular distance.

The above DPD simulation results strongly indicate that DOX and BIN could assemble to nanoaggregates in water, and BIN molecules are mainly distributed on the surface of nanoparticles, while DOX is distributed in the core of nanoparticles.

In theory, the chemical groups of different drug molecules can be combined through various intermolecular forces, such as π–π stacking, hydrogen bond, ionization, and van der Waals force. However, it is difficult to determine whether the combination is stable and whether nanoparticles are formed. Multiscale computer simulation-assisted designs have great advantages in solving the above problems [24]. Through molecular docking simulation, we can observe and compare the different intermolecular forces to verify whether the two different drug molecules tend to combine [25]. On this basis, the molecules are coarse-grained to beads through DPD mesoscopic simulation. And then, the shape and internal structure of nanoparticles can be directly observed on the computer, which provides a strong support for the preparation of nanoparticles. However, due to the limitation of computer resources, our bead setting in the DPD simulation is not fine enough to observe the distribution of intermolecular forces between DOX and BIN molecules in nanoparticles. On the basis of sufficient computer power, through the DPD simulation method based on beads representing chemical groups, the distribution of molecules in nanoparticles will be more finely simulated. By comparing with the results of all atom simulation results, it is expected to count the distribution of intermolecular forces in nanoparticles and give a more complete diagram of the internal assembly mechanism of nanoparticles [26, 27].

3.3. Characterization of DOX/BIN NPs

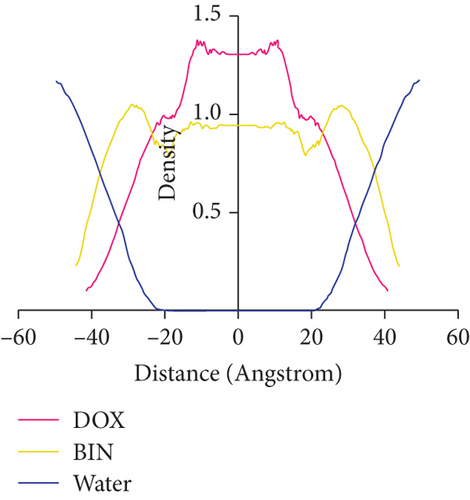

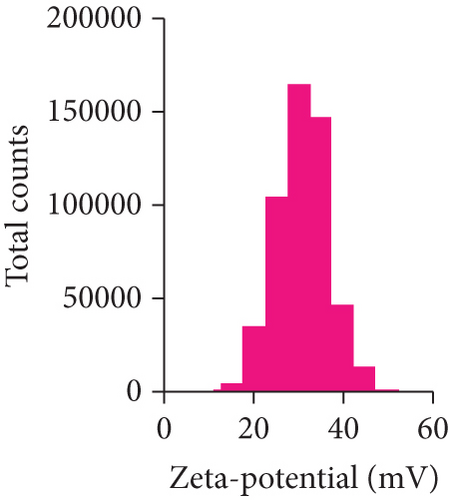

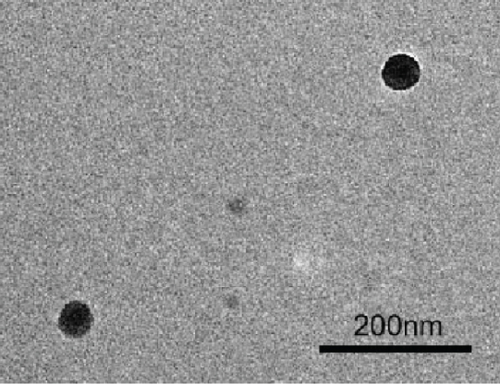

After mesoscopic simulation, DOX/BIN NPs were prepared by the dialysis method with a feed ratio (DOX : BIN = 1 : 1). As shown in Figure 6, the DOX/BIN NPs presented a turbid orange solution with a granular sensation. The particle size of DOX/BIN NPs was 317.3 ± 10.3 nm, and the zeta-potential was 31.0 ± 5.9 mV. Subsequently, the TEM images of DOX/BIN NPs were scanned and presented a spherical aggregate structure. The drug loading contents of DOX and BIN were 42.06% and 57.94%, respectively.

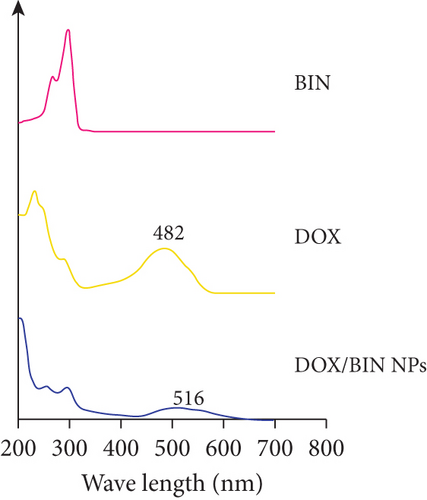

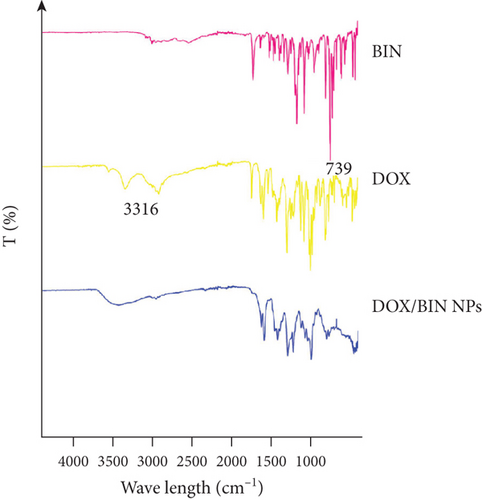

The results of molecular docking suggested that there is mainly π–π stacking and hydrogen bonding between DOX and BIN. Therefore, we further characterized the intermolecular forces in DOX/BIN NPs using the UV and IR absorption spectra. The ultraviolet spectrum showed that the absorption peak of DOX was at 482 nm, whereas the absorption peak of DOX/BIN NPs was at 516 nm (Figure 6(e)). This red-shift of the absorption peak indicated that the preparation of DOX/BIN NPs was successful. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) showed that the absorption bands at 3316 cm-1 of DOX, which represent the stretching vibration of the O-H group, were significantly reduced when it was assembled with BIN, suggesting that H-bonding occurred. In addition, the evident decreasing of the absorbance at 739 cm-1 of BIN indicated the association of hydrophobic parts (Figure 6(f)). These results suggest that the assembly of DOX and BIN is mediated by multiple noncovalent forces, including π–π stacking interactions and H-bonds. The results of the UV and FT-IR analysis were consistent with those of the AutoDock and DPD Mesoscopic simulations and further verified that π–π stacking interactions and H-bonds were the main forces driving the assembly of DOX/BIN NPs.

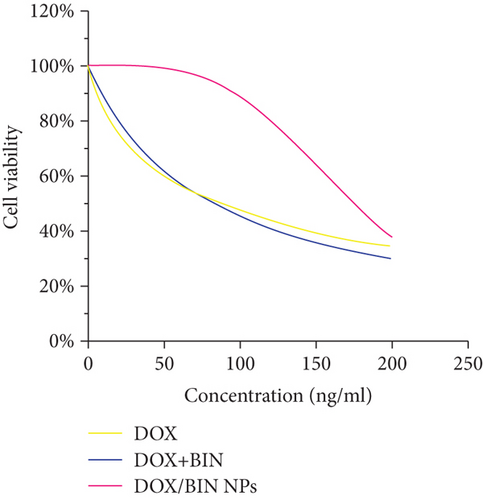

3.4. Cytotoxicity of DOX/BIN NPs

To test the antitumor activity of DOX/BIN NPs, a cytotoxicity assay was performed. The viability of retinoblastoma Y79 cells was inhibited by DOX/BIN NPs, and the antitumor activity was enhanced with increasing concentrations of DOX/BIN NPs (Figure 6(g)). When the concentration reached 200 ng/mL, the antitumor activity of DOX/BIN NPs was similar to that of DOX or DOX+BIN. The results indicated that DOX/BIN NPs might have the potential to be used in antitumor therapy.

4. Conclusion

In summary, a multiscale computer simulation was successfully applied to predict and design a novel doxorubicin nanomedicine with bindarit as a carrier. In this simulation, the strong intermolecular interactions (π–π stacking and H-bonding) between DOX and BIN were calculated as a basis for supporting the formation of a stable DOX/BIN complex. Additionally, the hydrophilicity analysis of the DOX/BIN complex revealed an amphiphilic structure, which indicates the potential assembly ability of the DOX/BIN complex in water. A mesoscopic simulation based on DPD methodology further demonstrated that the DOX/BIN complex can self-assemble to spherical aggregates wherein DOX is concentrated internally and BIN on the outer surface. Under the guidance derived from this multiscale computer simulation, DOX/BIN NPs were successfully and facilely prepared using a dialysis method against water. The produced DOX/BIN NPs showed a good uniform nanosize distribution profile, high charged surface characteristics, and effective antitumor activity inherited from DOX. Furthermore, the intermolecular forces in DOX/BIN NPs driving the assembly were demonstrated to be multiple noncovalent forces, including π–π stacking interactions and H-bonds, which is consistent with the results from the computational simulation. Although additional studies are needed to further investigate the in vivo antitumor activity of the DOX/BIN NPs, these findings suggest that this multiscale computer simulation approach is an effective design strategy to guide the development of novel nanomedicines using a drug with synergistic antitumor activity as a carrier. This may result in high safety and low production costs and may open an alternative way to fabricate novel nanomedicines in many fields of research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation Project of Chongqing, Chongqing Science and Technology Commission (Grant Nos. cstc2019jcyj-msxmX0603), Scientific Startup Fund of CQUT (Grant No. 2019ZD88), and Chongqing Science and Technology Program (Grant Nos. 30119-2961). The authors thank the Analytical & Testing Center of Sichuan University for the computing facilities.

Open Research

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.