Major Phytochemical as γ-Sitosterol Disclosing and Toxicity Testing in Lagerstroemia Species

Abstract

Medicinal plants in genus Lagerstroemia were investigated for phytochemical contents by GC-MS and HPLC with ethanol and hexane extracts and their toxicity MTT and comet assay on human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). γ-Sitosterol is the major component found in all species at 14.70–34.44%. All of the extracts, except for L. speciosa ethanol extract, showed high percentages of cell viability. The IC50 value, 0.24 mg/mL, of ethanol L. speciosa extract predicted an LD50 of 811.78 mg/kg, which belongs to WHO Class III of toxic chemicals. However, in-depth toxicity evaluation by the comet assay showed that the four tested species induced significant (p < 0.05) DNA damage in PBMCs. γ-Sitosterol was previously reported to possess antihyperglycemic activity by increasing insulin secretion in response to glucose. Nonetheless, consumers should consider its toxicity, and the amount of consumption should be of concern.

1. Introduction

Lagerstroemia species, including L. speciosa, L. loudonii, L. indica, L. villosa, and L. floribunda, were used worldwide as medicinal and ornamental plants. L. indica extract has been used for treating allergic diseases such as asthma due to its anti-inflammatory properties [1, 2], analgesic, antihyperglycemic, and antioxidant hepatoprotective effects [1], and antidiabetic activity by its containing corosolic acid [3]. L. speciosa and L. loudonii have also been reported for their chemical constituents [4, 5]. L. speciosa leaf extract containing corosolic acid as an active compound has been reported for diabetes treatment [6, 7]. The hypoglycemic effects of L. speciosa have been attributed to both corosolic acid and ellagitannins [8]. Current knowledge on the phytochemicals and pharmacology of L. speciosa has regarded it as a natural antidiabetes product, whose leaves contained triterpenes, tannins, ellagic acids, glycosides, and flavones [9].

Remarkably, out of all of the natural products for diabetes treatment, the L. speciosa species was registered as the one of the 170 medicinal plants in Thailand listed by Ministry of Public Health announcements. However, with diverse growth factors and environments in each area of the country, its chemicals should be clarified and toxicity tested, including both cytotoxicity and genotoxicity levels. Therefore, this research focuses on the information described above and includes the following four species: L. speciosa, L. indica, L. loudonii, and L. villosa.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

Leaves of Lagerstroemia speciosa, L. indica, L. loudonii, and L. villosa were collected and used to make the crude extracts by hexane and ethanol. Then, further studies on phytochemical analysis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), cytotoxicity by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay and genotoxicity by the comet assay were performed.

2.2. Phytochemical Extracts

The samples were rinsed with water and air-dried until the water evaporated from the leaves. A 20 g sample was then ground into a powder, mixed with 120 mL hexane or ethanol (analytical grade), separately for 72 h. Samples were filtered through a filter paper at room temperature, and the filtrates in this step were subjected to GC-MS analysis. For further experiments with the remaining filtrates, the solvents were evaporated with a rotary evaporator (Rotavapor R-210, Buchi, Switzerland) at 800–1,000 mbar, 15°C, and 600 rpm for 2 h. Dark green, thick, viscous crude extracts were obtained. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to the extracts until being completely dissolved and maintained as stock extracts at −20°C until the cytotoxicity and genotoxicity experiments were conducted.

2.3. Analysis of the Plant Extract Component by GC-MS

The analysis was performed using an Agilent Technologies GC 6890 N/5973 inert mass spectrometer fused with a capillary column (30.0 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm). Helium gas was used as the carrier at a constant flow rate of 1 mL/min. The injection and mass-transferred line temperature was set at 280°C. The oven temperature was programmed for 70°C to 120°C at 3°C/min, held isothermally for 2 min, and then raised to 270°C at 5°C/min. A 1 μL aliquot of the crude extract was injected in split mode. The relative percentage of the crude constituents was expressed as a percentage using peak area normalization. Component identification was determined by comparing the obtained mass spectra with the reference compounds in the Wiley 7N.1 library.

2.4. Analysis of the Plant Extract Component by HPLC

The amount of corosolic acid from L. speciosa (1 mg, Sigma Aldrich) was weighed and dissolved in 1 mL of ethanol for standard solution. Contents of corosolic acid from crude extracts were determined by HPLC, using Agilent Technologies 1260 Infinity, compared to the standard. The column Hypersil ODS C18, 4.0 × 250 mm, 5 Micron (Agilent) was used. The detection wavelength was 210 nm. The mobile phase consisted of two solvents: 0.1% phosphoric acid (A) and acetonitrile (B). The gradient elution was carried out by acetonitrile 55% to 100% (0–35 min). The flow rate was 1 mL/min, and 10 μL of the sample was injected.

2.5. Isolation of Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs)

PBMCs were isolated from sodium heparin anticoagulated venous blood from a blood bank using Ficoll-Paque Plus (GE Healthcare), as recommended. Freshly isolated PBMCs with viability of at least 98% were used for the toxicity testing. The cells were suspended at a concentration of 106 cells/mL in modified RPMI-1640 medium, with 2 mM L-glutamine and 25 mM HEPES, supplemented with 10% FBS, 5 μg/mL phytohemagglutinin (PHA), 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin.

2.6. Cell Preparations, Extract Treatments, and the MTT Assay for Cytotoxicity Testing

Upon testing, the primary crude extract concentrations were serially 10-fold diluted with water, for five levels as working concentrations. The prepared cells were seeded in 96-well plates, 125 μL per well. Another 12.5 μL of the proper extract working concentrations was added to the corresponding wells in triplicate. The cells were incubated for 4 h in a humidified CO2 incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. Corresponding DMSO concentrations were similarly prepared as vehicle controls. The untreated cells were used as a negative control, whereas the positive control cells were treated with UV light for 20 min.

At the end of the treatment, the plates were centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 10 min and the medium was removed by pipetting. The MTT (Sigma, USA) was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL in a volume of 10 μL per well. Then, the plates were wrapped with aluminum foil and incubated for 4 h at 37°C. After the formazan crystals were solubilized by adding 100 μL DMSO to each well, the plates were left in the dark for 2–4 h. The absorbance was read at 570 nm with a microtiter plate spectrophotometer (Fluorescence microplate reader; SpectraMax M5 series, Molecular Devices). Wells containing medium and MTT without cells were used as blanks. Each concentration treatment was performed in triplicate. All values were expressed as the mean ± S.D. Cellular reduction of tetrazolium salt, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), formed a violet crystal formazan through mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase activity of the viable cells, and the violet crystal formazan was quantified following the methods of Freshney [10]. Percentage of cell viability was calculated using the equation (cell viability (%) = average viable of treated cells/average viable of negative control cells × 100) to reveal the cytotoxicity of the plant extracts. Doses inducing 50% inhibition of cell viability (IC50 value) were determined by plotting a graph of the extract concentration against the cell viability. The IC50 value was used for the LD50 calculation [11] to release hazardous levels, according to the World Health Organization [12].

2.7. Genotoxicity Assay by the Comet Assay

The cells were treated as in the MTT assay with concentration at IC50 value or at a maximum-treated concentration, in case no IC50 value was detected. The alkaline comet assay was used to assess the genotoxicity of plant extracts, according to a method previously described by Singh et al. [13]. Briefly, the electrophoresis buffer consisted of 0.3 M NaOH and 1 mM EDTA (pH = 10). The power was supplied at a constant of 3.4 V/cm with an adjustment to 300 mA, for 25 min. To quantify the level of DNA damage, the extent of DNA migration was defined using the “Olive Tail Moment” (OTM), which is the relative amount of DNA in the tail of the comet multiplied by the median migration distance. The comets were observed at 200 magnifications and images were obtained using an image analysis system (Isis) attached to a fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Japan), equipped with a 560 nm excitation filter, 590 nm barrier filter, and a CCD video camera PCO (Germany). At least 150 cells (50 cells for each of triplicate slides) were examined for each experiment. The CASP software (Wroclaw, Poland) was used to analyze the OTM. The negative control was untreated cells, and the positive control was UV-treated cells. All experiments were in triplicate. The triplicate cultures were scored for an experiment. All values were expressed as the mean ± S.D. The nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis of the comet assay results; statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

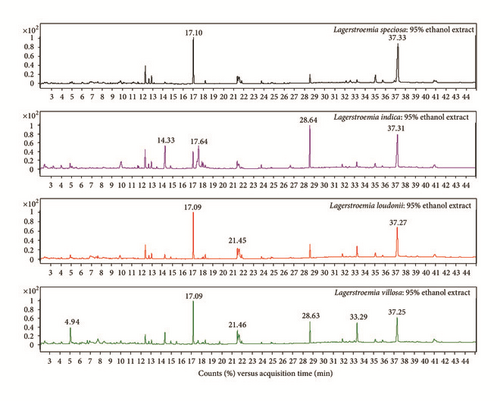

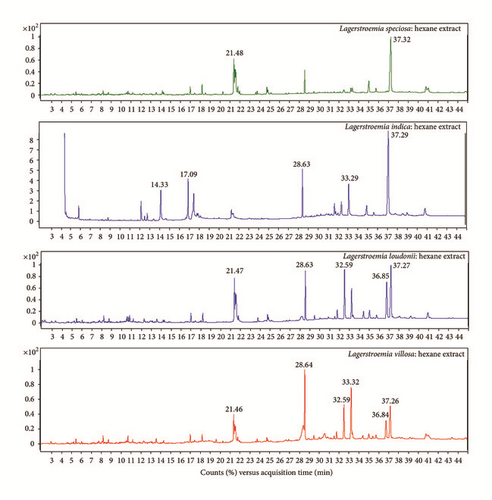

Phytochemical analysis of the filtrates from ethanol and hexane crude extracts (Figures 1 and 2) of the four studied samples as L. speciosa, L. indica, L. loudonii, and L. villosa revealed that there are several substances with some major components in higher amounts than others (Table 1). These are 34.4% γ-sitosterol, 19.1% phytol, 34.3% γ-sitosterol, and 27% (Z)-9-octadecenamide in L. speciosa; 13.5% squalene, 11.3% n-hexadecanoic acid, 11.2% linolenic acid, and 32.2% γ-sitosterol in L. indica; 23.2% γ-sitosterol, 18.4% phytol, 20.6% (Z)-9-octadecenamide, 18.4% γ-sitosterol, 12.6% octacosane, and 12.4% tetratriacontane in L. loudonii; 16.9% phytol, 12.8% (Z)-9-octadecenamide, 18.2% α-tocopherol, 16.2% (Z)-9-octadecenamide, 14.9% squalene, 14.7% γ-sitosterol, and 11.3% octacosane in L. villosa, with ethanol and hexane solvents, respectively. Analysis of the plant extract component by HPLC actually concentrated on corosolic acid findings, and the results showed no detection with hexane in L. speciosa and L. loudonii and a very small amount in the other studied species (Table 2).

| Compound | Formula | Relative content (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. speciosa (ethanol) | L. speciosa (hexane) | L. indica (ethanol) | L. indica (hexane) | L. loudonii (ethanol) | L. loudonii (hexane) | L. villosa (ethanol) | L. villosa (hexane) | ||

| γ-Sitosterol | C29H50O | 34.44 | 34.34 | 21.91 | 32.18 | 23.22 | 18.39 | 17.90 | 14.70 |

| (Z)-9-Octadecenamide (oleamide) | C18H35NO | 9.73 | 26.99 | 4.98 | 4.04 | 14.07 | 20.60 | 12.75 | 16.24 |

| Phytol | C20H40O | 19.10 | 1.93 | 5.24 | 7.31 | 18.44 | 1.51 | 16.89 | 1.71 |

| α-Tocopherol | C29H50O2 | 1.23 | 1.66 | 1.57 | 8.01 | 5.22 | 7.48 | 10.52 | 18.24 |

| Squalene | C30H50 | 3.06 | 5.99 | 13.54 | 9.24 | 5.15 | 8.74 | 8.42 | 14.89 |

| Octacosane | C28H58 | — | — | — | — | — | 12.63 | — | 11.31 |

| Tetratriacontane | C34H70 | — | — | — | — | — | 12.39 | — | 7.53 |

| n-Hexadecanoic acid | C16H32O2 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 11.29 | 7.40 | 1.93 | — | 5.18 | — |

| Linolenic acid | C18H32O2 | — | — | 11.19 | 6.36 | — | — | — | — |

| 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural | C6H6O3 | 0.60 | — | 1.98 | — | 1.61 | — | 8.54 | — |

| Phytol, acetate | C22H42O2 | 6.51 | — | 5.60 | 3.16 | 5.70 | 0.62 | 3.65 | — |

| Campesterol | C28H48O | 5.09 | 5.72 | 1.68 | 3.12 | 2.96 | 2.69 | 2.09 | 1.92 |

| Ethyl α-d-glucopyranoside | C8H16O | 2.44 | — | 5.27 | — | 2.40 | — | 1.62 | — |

| 3,7,11,15-Tetramethyl-2-hexadecen-1-ol | C20H40O | 4.83 | — | 3.25 | 1.89 | 3.46 | — | 2.05 | — |

| 1,2,3-Benzenetriol | C13H18O4 | 1.37 | — | — | — | 3.82 | — | — | — |

| Linoleic acid | C18H32O2 | — | — | 3.74 | 1.83 | — | — | — | — |

| Vitamin E ∗ | n/a | 1.74 | 3.50 | — | — | — | — | 3.13 | 1.35 |

| Stigmastan-3,5-diene | C29H48 | — | — | — | 3.30 | — | — | — | — |

| 24-Methylenecycloartanol | C31H52O | — | — | 2.09 | 3.04 | 3.27 | 2.16 | — | — |

| cis-11-Eicosenamide | C20H39NO | 0.41 | 3.25 | — | — | 0.60 | 2.00 | 0.79 | 0.71 |

| Stigmast-5-en-3-ol,oleate | C47H82O2 | — | 3.07 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| γ-Tocopherol | C28H48O2 | — | — | 1.00 | 2.65 | 1.35 | 1.76 | 1.42 | 1.88 |

| Hexadecanamide | C16H33NO | 1.25 | 2.52 | 0.55 | 0.31 | 1.79 | 1.58 | 1.57 | 1.66 |

| Tetratetracontane | C44H90 | — | — | — | — | — | 1.83 | — | — |

| Octadecanamide | C18H37NO | 1.06 | 1.80 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 1.18 | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.69 |

| α-Tocopherolquinone | C29H50O3 | — | 1.78 | — | — | — | 0.86 | — | 1.53 |

| Methane, tris(methylthio)- | C4H10S3 | — | — | — | 1.77 | — | — | — | — |

| Octadecanoic acid | C18H36O2 | — | — | 1.69 | 0.40 | — | — | — | — |

| Stigmasterol | C29H48O | 1.40 | 1.65 | 0.44 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.89 | 1.19 | 1.10 |

| Octadecane | C18H38 | — | 0.87 | — | — | — | 0.96 | — | 1.30 |

| Cycloartenol | C30H50O | — | — | — | 1.16 | — | — | — | — |

| Glycerol β-palmitate | C19H38O4 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.88 | — | 0.91 | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.64 |

| 17-Pentatriacontane | C35H70 | 0.96 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol | C9H10O2 | 0.94 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Lupeol | C30H50O | — | — | — | — | — | 0.94 | — | — |

| Hexadecanoic acid, ethyl ester | C16H32O2 | — | — | 0.87 | — | 0.76 | — | 0.94 | — |

| Pentacosane | C25H52 | — | 0.50 | — | — | — | — | — | 0.92 |

| Dodecane, 4,6-dimethyl- | C14H30 | — | 0.68 | — | — | — | 0.60 | — | 0.90 |

| Linolenic acid, ethyl ester | C18H30O2 | — | — | 0.89 | 0.62 | 0.75 | — | — | — |

| 1,30-Triacontanediol | C30H62O2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.78 |

| Cholesta-4,6-dien-3-ol | C27H44 | 0.78 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Tetracosane | C24H50 | — | 0.77 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1,2-Propanediol, 3-(1-pyrrolidinyl)- | C7H15NO2 | 0.72 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Tricosane | C23H48 | — | 0.70 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Docosane | C22H46 | — | 0.45 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid, ethyl ester | C18H32O2 | — | — | — | — | 0.41 | — | — | — |

| Dihydroactinidiolide | C11H16O2 | — | — | — | 0.34 | — | — | — | — |

| Olean-12-en-3-one | C30H48O | — | — | — | 0.32 | — | — | — | — |

| 5-Methoxy-2-oxoestra-1(10),3-dien-17-yl acetate | C21H28O3 | 0.30 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 7-Dehydrodiosgenin | C27H40O3 | — | — | — | 0.22 | — | — | — | |

| Diisooctyl phthalate | C24H38O4 | — | — | — | 0.16 | — | — | — | — |

| α-Hydroxymyristic acid | C14H28O3 | 0.14 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| α-Glyceryl linoleate | C21H36O4 | — | — | — | 0.11 | — | — | — | — |

- ∗Vitamin E refers to a class of compounds; n/a: not analyzed as individual compound by the Wiley 7N.1 library.

| Plant samples | Amount in each type of solvent (mg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Hexane | |

| L. speciosa | 0.068 | Not detected |

| L. indica | 0.0036 | 0.0015 |

| L. loudonii | 0.093 | Not detected |

| L. villosa | 0.125 | 0.0012 |

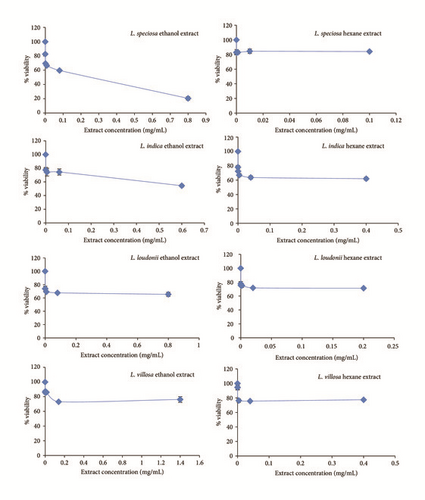

Mass of the crude extracts of the three samples derived from ethanol and hexane solvents is shown in Table 3. The extracts were subjected to serial 10-fold dilution for five levels, as used for the MTT assay.

| Plant | Solvent | Maximum extract conc. (mg/mL) | IC50 (mg/mL) | % cell viability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. speciosa | Ethanol | 8 | 0.24 | — |

| Hexane | 1 | — | 82.54 ± 2.52–84.45 ± 3.11 | |

| L. indica | Ethanol | 6 | — | 54.40 ± 2.15–77.46 ± 0.90 |

| Hexane | 4 | — | 62.02 ± 2.20–78.15 ± 2.41 | |

| L. loudonii | Ethanol | 8 | — | 67.62 ± 1.82–73.83 ± 3.85 |

| Hexane | 2 | — | 71.27 ± 0.72–77.60 ± 3.38 | |

| L. villosa | Ethanol | 14 | — | 73.18 ± 0.23–87.24 ± 1.17 |

| Hexane | 4 | — | 75.67 ± 0.35–94.72 ± 3.74 | |

The percentages of cell viability are 82.5 ± 2.5 to 84.5 ± 3.1 with hexane L. speciosa extract; 54.40 ± 2.15 to 77.46 ± 0.90 and 62.02 ± 2.20 to 78.15 ± 2.41 with ethanol and hexane L. indica extracts, respectively; 67.62 ± 1.82 to 73.83 ± 3.85 and 71.27 ± 0.72 to 77.60 ± 3.38 with ethanol and hexane L. loudonii extracts, respectively; and 73.18 ± 0.23 to 87.24 ± 1.17 and 75.67 ± 0.35 to 94.72 ± 3.74 with ethanol and hexane L. villosa extracts, respectively (Table 3, Figure 3). There is an IC50 value, 0.24 mg/mL, of ethanol L. speciosa extract, which refers to an LD50 of 811.78 mg/kg.

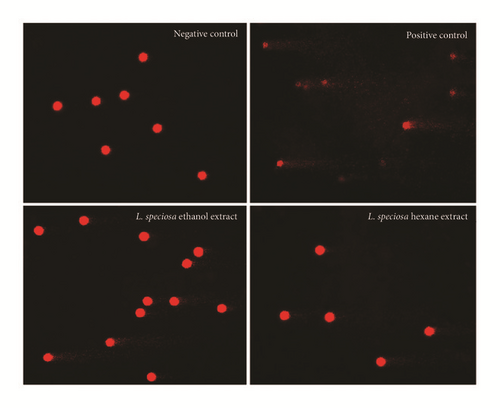

Because the ethanol L. speciosa extract and the ethanol and hexane L. indica, L. loudonii, and L. villosa extracts have no IC50 values and high % cell viability, the first highest diluted concentration extracts were selected for further step genotoxicity study as the comet assay. The results showed that, compared to negative control (untreated cells), the four tested species induced significant DNA damage in PBMCs (p < 0.05) (Table 4 and Figure 4).

| Plant | Solvent | Concentration (mg/mL) | Olive tail moment | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. speciosa | Ethanol | 0.24 | 0.21 ± 0.22 | <0.0001 |

| Hexane | 0.10 | 0.42 ± 0.28 | <0.0001 | |

| Negative control | — | 0.02 ± 0.03 | — | |

| L. indica | Ethanol | 0.60 | 3.84 ± 2.91 | <0.0001 |

| Hexane | 0.40 | 1.28 ± 1.24 | <0.0001 | |

| Negative control | — | 0.39 ± 0.36 | — | |

| L. loudonii | Ethanol | 0.80 | 0.66 ± 0.55 | <0.0001 |

| Hexane | 0.20 | 0.45 ± 0.35 | 0.0228 | |

| Negative control | — | 0.39 ± 0.36 | — | |

| L. villosa | Ethanol | 1.40 | 1.20 ± 0.50 | <0.0001 |

| Hexane | 0.40 | 0.60 ± 0.67 | <0.0001 | |

| Negative control | — | 0.39 ± 0.36 | — | |

4. Discussion

Since the announcement that L. speciosa and L. indica contain corosolic acid, which is used in the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes [3, 6–9], the species studied here have been widely used in both prepared and traditional forms worldwide. Conversely, this research found a large amount of γ-sitosterol (14.7–34.4%) in all four of the studied species. Through GC-MS supported information by HPLC, lack or a small amount (0.002–0.07 mg/mL) of corosolic acid was detected. The quantity found leads to an assumption that corosolic acid may not be a factor in the treatment of diabetes. Currently, γ-sitosterol, an epimer of β-sitosterol, has been insisted to possess antihyperglycemic activity by increasing insulin secretion in response to glucose confirmed with immune histochemical study of pancreas [14, 15]. Additionally, Sundarraj et al. [16] demonstrated in vitro results that support the ethnomedical use of γ-sitosterol against cancer through the growth inhibition and cell cycle arrest on the apoptosis of cancer cells in accord with Endrini et al. [17], which showed that γ-sitosterol was cytotoxic against colon and liver cancer cell lines and that this effect was mediated by downregulation of c-myc expression and induction of the apoptotic pathways. Currently, studies in the many plant species where γ-sitosterol is found, such as in Girardinia heterophylla [18] and Lippia nodiflora [14], agree with the four studied Lagerstroemia species, the highest level found in L. speciosa and followed by the level in L. indica. The other substances in small amounts were quoted as phytol, (Z)-9-octadecenamide (oleamide), squalene, n-hexadecanoic acid, linolenic acid, octacosane, tetratriacontane, and α-tocopherol, most of which are beneficial in humans; for examples, oleamide is a protective agent against scopolamine-induced memory loss and is suggested as useful as a chemopreventive agent against Alzheimer’s disease [19], and it induces deep sleep [20] and the upregulation of appetite [21, 22]. Squalene is a triterpene necessary for life. In the human body, it is a natural and essential component used for the syntheses of cholesterol, steroid hormones, and vitamin D. It may also be an anticancer substance, as it possesses chemopreventive activity [23, 24]. Phytol is a diterpene alcohol that can be used as a precursor for the manufacture of synthetic forms of vitamin E [25] and vitamin K1 [26] and is used in the fragrance industry and in cosmetics, shampoos, toilet soaps, household cleaners, and detergents. Its worldwide use has been estimated to be approximately 0.1–1.0 metric tons per year [27]. Hexadecanoic acid or palmitic acid and linolenic acid are types of fatty acids. Octacosane is an alkane, which has been used as a lubricant, transformer oil, and anticorrosion agent; parts of the paraffin or wax are chemically inactive (http://chemicalland21.com/industrialchem/organic/n-OCTACOSANE.htm). Each phytochemical actually has specific functions, but they may potentially not be known at all. Therefore, the tests for total substance contents, for human safety usage without toxicity, are further experiments of cytotoxicity and genotoxicity levels.

The mass showed higher concentration with ethanol solvent than hexane in all four studied species (Table 3). These assumptions are caused by the fact that polar phytochemicals dissolve more easily in ethanol because it is a more polar substance than the hydrocarbon hexane, which is part of the nonpolar group. The vehicle control (DMSO) was performed for every tested concentration, and it was demonstrated that DMSO does not induce cell death at the highest tested concentration (10%) in PBMCs, so the effects mentioned above can only be attributed to the plant extracts’ bioactive compounds (data not shown). Therefore, it was not a surprise that IC50 with cytotoxicity appeared in the ethanol L. speciosa extracts, but not in the hexane extracts, when the same species were studied.

The MTT assay led to a LD50 at 811.78 mg/kg. The extrapolated data on predicted LD50 dose demonstrated that all tested compounds of L. speciosa belong to the WHO Class III (over 500 mg/kg body weight, oral), slightly hazardous category of toxic chemicals. For the evaluation of toxicity, 50 kg body weight would have to consume possibly a dose of 25,000 mg, to reach this level. However, consumers should see more toxicity by the in-depth comet assay. The first highest 10-fold diluted concentration extracts were selected for comet assay for the following reasons: firstly, to have the nearest concentration at usually human consuming of plant parts and secondly, to have not used more than 10% DMSO concentration for final 1% concentration, to avoid affecting on cells.

The results showed that, compared to negative control (untreated cells), the four tested species induced significant DNA damage in PBMCs (p < 0.05). Untreated cells for the negative control appeared as spherical nucleoids with no DNA migration. In the case of the positive control (UV-lighted cells), the gradual increase of strand breaks was evident, and they were represented as cells with a long tail of DNA streaming out from the nucleoid, forming a comet-like appearance (Figure 4).

5. Conclusion

The phytochemical γ-sitosterol found in high amount in the two studied species, L. speciosa and L. indica, was very interesting, but consumers should consider toxicity of the plants.

Competing Interests

The authors report no conflict of interests regarding this research.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Khon Kaen University’s Graduate Research Fund Academic Year 2015 (Grant no. 58132101), Buriram Rajabhat University, and the 2015 TTSF Science & Technology Research Grant by Toray Science Foundation (TSF), Japan.